Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has emerged as a pervasive global health concern, for which there are no known curative treatments. Consequently, there is an imperative for the implementation of preventive and kidney-protective strategies. The renal kallikrein–kinin system (KKS) is a vasodilator, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic pathway located in the distal nephron, whose decline contributes to hypertension and CKD progression. In this narrative, non-systematic review, a thorough evaluation of both experimental and clinical data was undertaken to ascertain the interactions between dietary potassium, renal KKS activity, and kidney protection. A particular emphasis was placed on animal models of proteinuria, tubulointerstitial damage, and salt-sensitive hypertension, in conjunction with human studies on potassium intake and renal outcomes. A body of experimental evidence suggests a relationship between potassium-rich diets and renal kallikrein synthesis, urinary kallikrein activity, and up-regulated kinin B2 receptor expression. Collectively, these factors have been shown to result in reduced blood pressure, oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, and these effects are counteracted by B2 receptor blockade. In humans, higher potassium intake has been shown to enhance kallikrein excretion and lower cardiovascular and renal risk, independently of aldosterone. Conversely, low potassium intake has the potential to exacerbate CKD progression. Notwithstanding the concerns that have been raised regarding the potential necessity of increasing potassium intake in cases of advanced CKD, extant evidence would appear to indicate that potassium excretion persists until late disease stages. The activation and preservation of the renal KKS through a potassium-rich diet is a rational, cost-effective strategy for renoprotection. When combined with sodium reduction and nutritional education, this approach has the potential to halt the progression of CKD and enhance cardiovascular health on a population scale.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been identified as a significant public health concern on a global scale. The prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has increased by 40% between 2003 and 2016 [1], and this trend will continue to rise, driven by obesity, hypertension, and diabetes pandemic, coupled with increased life expectancy and lower mortality. This will guarantee the sustained rise in the number of patients necessitating renal replacement therapies [2]. In light of the present circumstances, wherein a cure remains elusive for numerous acquired kidney diseases and accessible gene therapy for genetic forms of nephropathy is not yet available, it is imperative to prioritize prevention and kidney protection. In light of these considerations, it is imperative to formulate optimal strategies that comprehensively support patients throughout their arduous journey to dialysis and that are aimed at preserving their kidney function to the greatest extent possible [3].

In this regard, intensive efforts have been made. These efforts include effective management of the primary disease, adequate blood pressure control, and, more recently, the introduction of measures to reduce compensatory hyperfiltration, proteinuria, and progressive renal fibrosis.

The renal kallikrein-kinin system (KKS) is a significant vasodilator system situated in the renal tubulointerstitial compartment [4]. It has been associated with renoprotective properties. The stimulatory effect that a high potassium intake has on the activity of this system is well documented.

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed using the keywords potassium, kidney protection, renoprotection, kallikrein, and kinins, including original research and reviews without restriction of date of publication. The search yielded a substantial body of experimental and observational information which was then compiled to produce a narrative review. This review supports the hypothesis that a potassium-rich diet may induce kidney protection in humans.

2. The Progressive Nature of Kidney Disease

Proteinuric glomerulopathies represent a primary etiology of chronic kidney damage exemplifying the progressive nature of renal injury. They primarily affect the glomerulus by altering the selectivity of the glomerular filtration barrier which results in proteinuria and subsequent progressive deterioration of kidney function. A substantial body of research has evidenced the nephrotoxicity of proteinuria and its underlying mechanisms, encompassing the activation of transcription factors in renal tubular cells, the production of proinflammatory cytokines, the recruitment of leukocytes, the development of tubulointerstitial inflammation, and the production of profibrogenic factors [5]. The result is the established correlation between proteinuria, tubulointerstitial damage, and fibrosis, a finding with full applicability to human kidney disease [6,7,8]

The process of interstitial fibrosis is preceded by several distinct biological events, including leukocyte infiltration, the release of inflammatory mediators, the differentiation of resident cells, the proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts, tubular dilation, local activation of the renin-angiotensin system, and the release of vasoconstrictive substances. The aforementioned events result in an aggregate increase in protein deposition within the extracellular matrix [9,10]. In addition to the damage to the tubulointerstitium and the activation of vasopressor mechanisms, there would be a reduction in the activity of vasodilator systems. There is a broad consensus in the scientific community that the extent of tubulointerstitial damage plays is a pivotal factor in the progression of CKD. Its damage has been identified as a reliable marker of a worse prognosis, particularly with regard to accelerated functional decline [11]. Consequently, it appears rational to concentrate available efforts on achieving effective protection of the tubulointerstitium,

3. The Renal Kallikrein-Kinin System

This is a multienzymatic complex located in the tubulointerstititial space of the kidneys. Its major components include an enzyme (renal kallikrein, KLK1), its substrates (renal high- and low-molecular-weight kininogens), effector bioactive peptides (kinins: lys-bradykinin and bradykinin), the kinin metabolizing enzymes (angiotensin-converting enzyme and neutral endopeptidase, among others), the kinin receptors (B1 and B2) and several activators/inhibitors of the system [12]. Kallikrein production occurs in connecting tubule cells in the renal cortex [13], whereas its substrates, the kininogens, are synthesized downstream in collecting tubule cells [14]. The anatomic vicinity of cells responsible for synthesizing both components facilitate kinin formation and action at the luminal side of the distal nephron cells as well as in the peritubular space [15]. This affects renal blood flow and electrolyte and water excretion. Another salient anatomical feature pertains to the close proximity observed between connecting tubule cells and the glomerular vascular pole in both the human and rat kidneys. This proximity is particularly evident with respect to the afferent arteriole (juxtaglomerular cells), which serves as the site of renin synthesis and storage (Figure 1). This anatomical proximity underscores a pivotal physiological relationship between the vasopressor and vasodepressor systems, highlighting their role in regulating renal blood flow. The biological effects of kinins are produced by the stimulation of two G protein-coupled receptors: B2R, constitutive and ubiquitous, and B1R, which is expressed at a very low level but is up-regulated in inflammatory states or in vitro by cytokines or TNF [16]. Bradykinin (BK) is a nonapeptide that exhibits effects on B2R; B1R is activated by BK metabolites, specifically des-Arg9-BK and Lys-des-Arg9-BK [4,17].

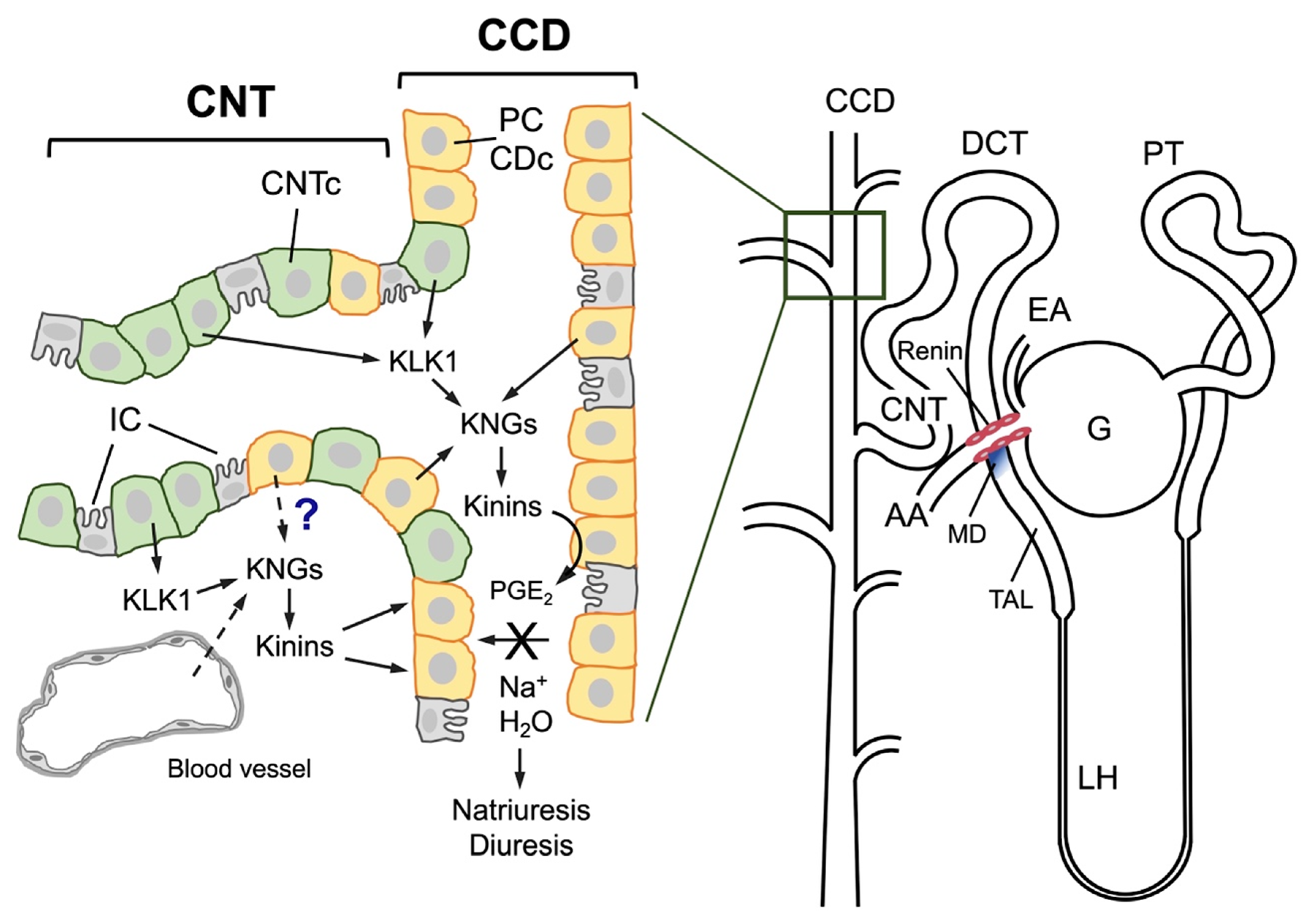

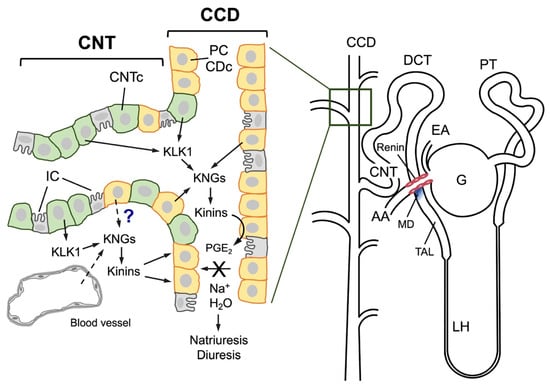

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the human nephron (right) and the major characteristics of the junction between the connecting tubule and the cortical collecting duct (left). A human nephron is represented, and its different segments are identified: G, glomerulus; EA, efferent arteriole; PT, proximal tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; LH, loop of Henle; TAL, thick ascending limb of Henle; CNT, connecting tubule; CCD, cortical collecting duct. An anatomical relationship is established between the afferent arteriole (AA), the connecting tubule, and the macula densa (MD), labeled in blue at the end of the TAL; renin is synthesized in the muscular cells of the afferent arteriole (pink cells). In the distal nephron, cells of both CNT (CNTc, pale green cells) and CCD (orange cells known as collecting duct cells, CDc, or principal cells, PC) intermingle over a certain distance. CNTc produce and secrete renal kallikrein (KLK1) into the tubular lumen and the tubulointerstitium, and CDc/PC produce kininogens (KNGs), making kinin production feasible in both the urinary fluid and the interstitium. Both the CNT and CCD also have intercalated cells (gray cells), which are not involved in kallikrein or kininogen synthesis. It is still unknown whether kininogens are secreted by CDc/PC or are filtered from interstitial capillaries into the interstitium. Once formed, kinins may stimulate the release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from CDc/PC that in turn inhibits sodium and water reabsorption, resulting in diuresis and natriuresis.

The cardiovascular and renoprotective roles of the kinin pathway, particularly mediated by B2R are recognized, conversely, the B1R role in renal disease appears to be deleterious [18,19,20,21]. Studies in mice with induced hypertension shows that B1R expression is increased in the kidney and that its genetic elimination decreases markers of inflammation and renal fibrosis. Likewise, the absence or blockade of this receptor reduces inflammatory markers (TNF, IL-6, IL-1β), fibrosis, and the production of reactive oxygen species in renal tissue [22]. In experimental models of acute kidney injury (AKI) with progression to CKD, the absence or antagonism of B1R preserves renal function and prevents fibrosis compared to controls, implying that B1R facilitates the transition from acute to chronic damage [23] and in a model of renal fibrosis due to ureteral obstruction, B1 receptor antagonism reduces renal fibrosis in a manner similar to angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonism, suggesting a pathogenic role for B1R in renal fibrogenic progression [18].

The kinin B2R, which has been revealed to be constitutively expressed not just in the kidney but also in a variety of different cell types [4], is the primary mechanism by which kinin peptides produced within the kidney operate in a paracrine manner [24]. A primary target of kinin action is the collecting duct cell, which expresses kinin B2R on both the basolateral and luminal cell membranes. Selective antagonists are available for this ligand: the most widely used in experimental settings is Icatibant, formerly known as HOE140 [25], and the slow-release Deucrictibant, recently developed to abort attacks of hereditary angioedema [26]

A substantial body of research involving animal models has demonstrated the critical role of the renal KKS in regulating blood pressure. A decline in kallikrein activity has been repeatedly observed in various hypertension models [27,28]. These findings are consistent with the observations made in human subjects, where a decrease in urinary kallikrein levels has been documented in individuals diagnosed with essential hypertension [29], salt-dependent hypertensive individuals who show reduced urinary kallikrein levels compared to salt-resistant individuals [30], and evidence of the hypotensive effect of pharmacological administration of KKS components to hypertensive subjects. While acknowledging the established role of hypertension in the progression of chronic kidney disease, it is imperative to expand the discourse beyond the confines of blood pressure regulation. The significance of proper KKS function extends beyond this scope, encompassing a broader spectrum of health implications. It is imperative to acknowledge the diverse array of biological functions exhibited by kinins, which encompasses the inflammatory process [31]. These peptides have been observed to possess an anti-inflammatory effect that appears to be contingent upon the B2R, thereby reducing cell migration [32].

Our group has been conducting research into the role of renal KKS in the pathogenesis of hypertension associated with kidney damage. To this end, experimental models of non-immune tubulointerstitial damage that lead to salt sensitivity have been utilized, including 5/6 nephrectomy, inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) synthesis with L-NAME, and the model of proteinuria due to intraperitoneal albumin overload [33]. In the various models examined, particularly in the albumin overload model [34], significant downregulation of KKS [33,34,35,36] has been demonstrated. This deficiency, which manifests during the induction of damage and persists for an extended period, has been substantiated through both histological examinations (employing immunohistochemical techniques specific for renal kallikrein) and urinary kallikrein enzyme activity measurements. The alteration is most likely associated with tubulointerstitial damage induced by proteinuria, which involves the structures where the key enzyme is produced. This results in a reduction in the immunoreactive kallikrein detected by immunohistochemistry. To date, there have been no studies that have examined the levels of renal kininogens in any of these experimental models.

Therefore, it is imperative to elucidate the relationship between proper function, or the necessary preservation of the KKS, to achieve a possible renoprotective effect. Reduced kallikrein levels in patients with mild or advanced renal failure are of particular relevance [37,38], as are human data associating a higher incidence of chronic renal failure to the presence of polymorphisms in the kallikrein [39] and kinin B2R genes [40].

4. Relations Between KKS and Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System (RAAS)

In recent years, there have been notable research efforts aimed at understanding the role of RAAS in hypertension and also in the progressive nature of CKD [41]. However, equal attention has not been paid to counter-regulatory systems, particularly the KKS. This is surprising, given that both systems are located in the kidney, share some components, are anatomically close to each other, and even act on similar effectors [42].

A significant consideration regarding the potential renoprotective role of kinins emerges from the postulate that these peptides may play a role in the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) drugs. ACE inhibitors, which reduce angiotensin levels while increasing kinin levels by reducing their catabolism, have been shown to reduce proteinuria, the severity of glomerulosclerosis, the intensity of tubulointerstitial damage, and fibrosis in several experimental models [43]. The drugs in question, utilized in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular diseases [44,45], have been observed to experience a significant reduction in efficacy when kinin receptors are blocked with specific antagonists [46]. This approach is particularly salient in light of the widespread use of ACEi within the domain of contemporary medicine. Extant research has demonstrated the efficacy of ACEi in reducing proteinuria and the risk of developing end-stage renal disease in human diseases [47]. ACEi have been shown to offer protection against the development of glomerulosclerosis through mechanisms that are not directly related to their antihypertensive action. This protective effect of ACEi is believed to be mediated, at least in part, by a reduction in fibronectin production: This effect that can be attenuated by the use of HOE 140, a kinin B2R antagonist [48]. A potential antifibrotic role for KKS has been proposed through the use of kallikrein siRNA, which has been demonstrated to increase the production of tissue plasminogen activator, fibronectin, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [49].

It is noteworthy that ACE is also referred to as kininase II, which is defined as an enzyme capable of inactivating kinins in the circulation [50]. Notwithstanding the preceding characterization of genetic alterations associated with ACE hyperactivity, and consequently diminished kinin availability of kinins due to heightened catabolism, which may exacerbate organ damage in diabetes mellitus or circumstances of cardiac or renal ischemia [51,52]; genetic inactivation of KLK1 kallikrein and kinin receptors has demonstrated analogous outcomes [51,52,53,54,55].

ACEi were originally developed for treatment of hypertension by inhibiting the formation of angiotensin II. Subsequent studies revealed the efficacy of these drugs in conditions involving excessive vasoconstriction, including heart failure and diabetic nephropathy. ACE inhibitors have been shown to have a general cardiovascular protective role in high-risk individuals [56]. Research conducted on both experimental models and human subjects has documented an increase in circulating kinin levels during the use of ACEi. Furthermore, a loss of the tissue-protective effect has been observed in animals deficient in kallikrein, kinins, or kinin receptors, as well as in those treated concomitantly with a kinin B2R antagonist [57,58]. Those experiments provide substantial evidence that kinins play a role in the multiple beneficial effects of ACEi in the cardiorenal field [59]. However, this hypothesis has been met with some skepticism by a few researchers [60]. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists, which are widely used to treat hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes-related kidney disease, appear to offer benefits to the kidneys that are analogous to those of ACEi. While it was initially hypothesized that ACEi would demonstrate superior cardiovascular benefits due to their capacity to augment kinin levels, it was subsequently revealed that “sartans” could also increase kinin levels, potentiating the kinin B2R activity. Indeed, the cardiac, renal, and vascular effects of angiotensin AT1 receptor blockade are not observed in animals deficient in kallikrein or the kinin B2R, nor in those with pharmacological B2R blockade [61,62,63,64]. It has been demonstrated that other pharmaceuticals employed in the domain of cardiovascular medicine, which were originally developed for the treatment of heart failure to protect against natriuretic peptide catabolism, such as neprilysin metallopeptidase inhibitors, have been observed to elevate kinin levels. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that neprilysin is also an effective kininase [65]. Furthermore, pharmacological activation of KLK1 kallikrein synthesis was demonstrated for aliskiren, a direct renin inhibitor, in experimental models of heart failure [66].

5. Renoprotective Potential of the KKS

Studies of mice lacking the kinin B2R (B2-KO) have yielded intriguing findings regarding renal and cardiovascular alterations. A preliminary investigation by Madeddu and colleagues revealed that a specific strain of this type exhibited marginally elevated blood pressure, cardia chamber distention and reparative fibrosis when compared to the control animals, under baseline conditions. The study also documented salt sensitivity [67]. These findings were discussed by other authors who did not find the same results when working with other strains of animals carrying the same defect [68]. The renal and cardiovascular benefits induced by the kinins are mediated by NO, formerly known as endothelium-derived vasorelaxant factor. This explains its potential as a therapeutic option for hypertension and its main consequences, left ventricular hypertrophy and renal disease [58].

A second approach in this regard was used by Uehara et al. [69,70], who, by administering sub-pressor doses of purified rat urinary kallikrein, managed to attenuate renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats, with a reduction in proteinuria and improvement in glomerular filtration. The effect in question is hypothesized to be mediated by kinin B2R, as the administration of Icatibant (HOE140) resulted in its complete abolition [71].

A third and highly effective approach was implemented by those who inoculated the kallikrein gene into rats with chronic kidney damage induced by 5/6 subtotal nephrectomy, achieving attenuation of hypertension, reduction of albuminuria, and protection against kidney damage (sclerosis and tubulointerstitial damage) and cardiac remodeling [72]. An increase in urinary kinin levels and a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance were observed, consistent with the results of purified enzyme infusion tests. A comparable outcome was observed in Dahl salt-sensitive rats, which was attributed to a reduction in oxidative stress and TGF-β1 expression [73,74,75]. From this same perspective, experiments in transgenic mice that overexpress the human kinin B2R are also relevant because these mice exhibited a propensity for hypotension and enhanced renal function in comparison to the control group. This phenomenon is attributed to the mediation of NO and it can be abolished by a B2R antagonist [76].

Given the extant evidence, it is worthwhile to investigate the potential of oxidative stress inhibition as a mediator of renal protection. Several studies [75,77] have examined the role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of kidney damage. Some findings indicate a link between salt sensitivity and oxidative stress, as well as intrarenal angiotensin activation [78].

It is imperative to acknowledge that renal fibrosis is an inevitable consequence of excessive extracellular matrix accumulation that occurs in virtually any type of progressive kidney disease [79] and that, from a simplistic point of view, renal fibrosis represents a failed healing process. This process, which includes several pathways such as mesangial and fibroblastic activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transformation EMT), is centrally regulated by TGF-β [80,81]. It has been postulated that these factors may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic nephropathies. Specifically, they have been shown to alter the degree of renal dysfunction, modifying the degree of cell proliferation, and the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins. As previously documented, the renal protection achieved through tissue kallikrein (KLK1) transfection is accompanied by a reduction in TGF-β expression [75]. Concurrently, evidence from experimental models of acute and chronic renal damage has demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect of KKS, as evidenced by a reduction in inflammatory cells and proinflammatory cytokines [82]. However, it has not yet been clearly demonstrated that stimulation of kinins reduces TNF-α production [83]. It is tempting to hypothesize that the anti-inflammatory effect observed in various models of renal injury following kallikrein administration or enhancement of kinin activity may result from a primary involvement in reducing the effects of TGF-β in the inflammatory milieu.

The mechanisms explaining by which the KKS may reduce oxidative stress and apoptosis have been thoroughly delineated in others sources [84]. Kinins have been demonstrated to stimulate the production of nitric oxide (NO) and cGMP, both of which are recognized as relaxing factors that reduce vascular tone and enhance renal hemodynamics [4]. Increased renal NO levels in association with reduced NADH/NADPH oxidase activity and superoxide anion formation are involved in a reduction of oxidative stress [75], an effect that seems to be mediated via kinin B2R [85]. Kinins, a class of compounds known for their vasodilatory properties, have been observed to elicit a response from endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS/NOS3) via the B2R receptor. This response is characterized by a modest and transient production of NO which is subsequently followed by the activation of inducible NOS (iNOS/NOS2) via the B1R receptor. This subsequent activation facilitates a more substantial and protracted release of NO, as previously documented in the extant literature [86]. Oxidative stress has been identified as a contributing factor to the induction of tubular epithelial cell death, a process that is mediated by caspases and/or endonucleases [87]. This process involves the activation of p38 MAPK specifically in the context of cisplatin-associated renal damage [88]. A relationship has been established between kinins and hemoxygenase-1 in hearts submitted to ischemia/reperfusion, where bradykinin pretreatment improves post-ischemic performance and infarct size, which is partially abrogated by the previous use of an HO-1 inhibitor [89]. In other cells (brain astrocytes) bradykinin induced HO-1 expression and enzymatic activity via a kinin B2R activated ROS-dependent signaling pathway [90].

In the course of functional renal parenchyma loss and fibrosis establishment, it is necessary to comprehend the role of cellular apoptosis, given its importance in preserving cellular homeostasis under both physiological and pathological conditions [91]. The available evidence suggests a link between apoptosis and the progression of renal damage progression [92,93,94,95]. Furthermore, there is evidence of the pleiotropic effects of the KKS on the myocardium [96] which has been shown to reduce apoptosis in tissue ischemia models. Concurrently, the hypothesis has been postulated that oxidative stress may directly promote programmed cell death in experimental models [97]. Evidence of the relationship between apoptosis and oxidative stress in experimental models of hypertension is also available [98] and there are reports showing that strict antihypertensive control can reduce apoptosis during kidney damage [99]. Therefore, would be beneficial to explore the potential of stimulating the KKS to modify the apoptosis demonstrated in proteinuria models [100], its involvement in the phenomenon of fibrotic transformation and its relationship with oxidative stress, as has been demonstrated in experimental hypertension.

The renoprotective effect of KKS has been postulated on the basis of observations in experimental models of acute renal injury. Rats administered gentamicin exhibited a significant decrease in urinary kallikrein levels, indicating that this downregulation may be relevant for the development of acute renal failure [101]. Furthermore, tissue kallikrein (KLK1) administration has been shown to prevent promote recovery of gentamicin-induced renal injury by inhibiting apoptosis, inflammatory cell recruitment, and fibrotic lesions. This process occurs through the suppression of oxidative stress and production of proinflammatory mediators [82]. The suppression of oxidative stress has been associated with diminished C-jun N-terminal kinase activation, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and TGF-β, through a kinin B2R- signaling pathway [84].

6. KKS Intervention and Kidney Protection

A comprehensive body of research has thoroughly documented the physiological role of endogenous kinins in the cardiovascular system and the kidneys, with studies conducted in both animal models and humans [102]. In various situations related to ischemia or chronic hypoglycemia, kinins have been demonstrated to have an organ-protective effect, particularly in the heart and kidneys. In a variety of pathological circumstances, a deficiency of kallikrein, kinins, or kinin B2R has been demonstrated to be a contributing factor to tissue damage [59]. Kinins have been demonstrated to exert their protective effect through the kinin B2R, inducing collateral vasodilation, reducing oxidative stress, and stimulating angiogenesis [103,104,105,106]. The utilization of models of loss of function has facilitated the demonstration of a reduction in the area of infarction, the prevention of ventricular remodeling in the heart, and tissue protection in the kidney under conditions of ischemia-reperfusion [102]. In the context of lupus nephritis, the KKS has been observed to fulfill a dual role, exhibiting both protective effects against tissue ischemia and fibrosis, and regulatory functions in inflammatory responses. In a noteworthy line of research, Liu et al. [107] demonstrated that specific strains with upregulation of renal and urinary kallikreins exhibited less severe disease. Furthermore, antagonizing the KKS increased disease severity, while agonist use attenuated it.

It deserves to be commented that although newer orally bioavailable B2R antagonists such as deucrictibant which enable sustained receptor blockade, the available long-term renal safety data remains limited [26,108]. Given the physiological role of B2R in renal hemodynamics, natriuresis, and tubular function, its chronic antagonism may theoretically impair renal homeostasis in susceptible individuals. Consequently, it is recommended that renal function, electrolyte levels, and blood pressure be monitored periodically during prolonged treatment.

The utilization of pharmacological interventions to augment the activity of the kallikrein-kinin system and its therapeutic value has been a subject of extensive research for a considerable period of time [109]. The application of gene therapy with human KLK1 has yielded positive outcomes in the treatment of cardiac and renal ischemia as well as diabetes [110,111,112,113,114,115]. Despite the current paucity of evidence in nephrology, the utilization of kallikrein as a therapeutic agent poses significant challenges due to pharmacokinetic considerations [116] and the interference with kinin B1 and B2 receptors by pharmaceutical agents [117,118].

It is noteworthy that the human phenotype of mutations that induce renal KLK1 dysfunction has not been associated with cardiovascular or renal diseases. This phenomenon could be attributed to the low frequency of these alleles, indicating that the study population may have been limited to subjects with partial functional deficiency and heterozygosity [102].

Research conducted with experimental models involving kinin B2R-deficient animals or pharmacologically blocked receptors has demonstrated that the cardiovascular benefits of kinins are predominantly mediated by the kinin B2R. This phenomenon has been primarily investigated in models of renal and cardiac ischemia. Research on diabetic animals and their renal complications suggests that diabetic nephropathy generally worsens in the absence of kinin B2R stimulation due to genetic deletion or deficiency in animals without kallikrein [119]. In a similar manner, the beneficial effect of ACEi on diabetic nephropathy can be suppressed in mice and rats with the use of a kinin B2R antagonist such as Icatibant (HOE140) [120,121]. The significance of kinin B2R activation has prompted research and development of new agonists, especially since bradykinin is rapidly catabolized by peptidases [50]. However, these agonists have not yet been adopted for clinical use due to the high rate of adverse effects, including angioedema, pain, and hypotension [53,57,59,122,123]. These adverse effects might be related to dosage or potency. Although not yet confirmed, the potential carcinogenic effect associated with the activation of the kinin B2R in relation to the use of ACEi is a matter of concern [124].

Experiments in salt-sensitive hypertension have demonstrated that taurine, a conditionally essential amino acid, when used pharmacologically, has the capacity to stimulate kallikrein synthesis, decrease atrial pressure, and induce a renoprotective effect, as evidenced by a reduction in proteinuria [125].

7. Stimulation of the KKS Through Potassium-Rich Diets

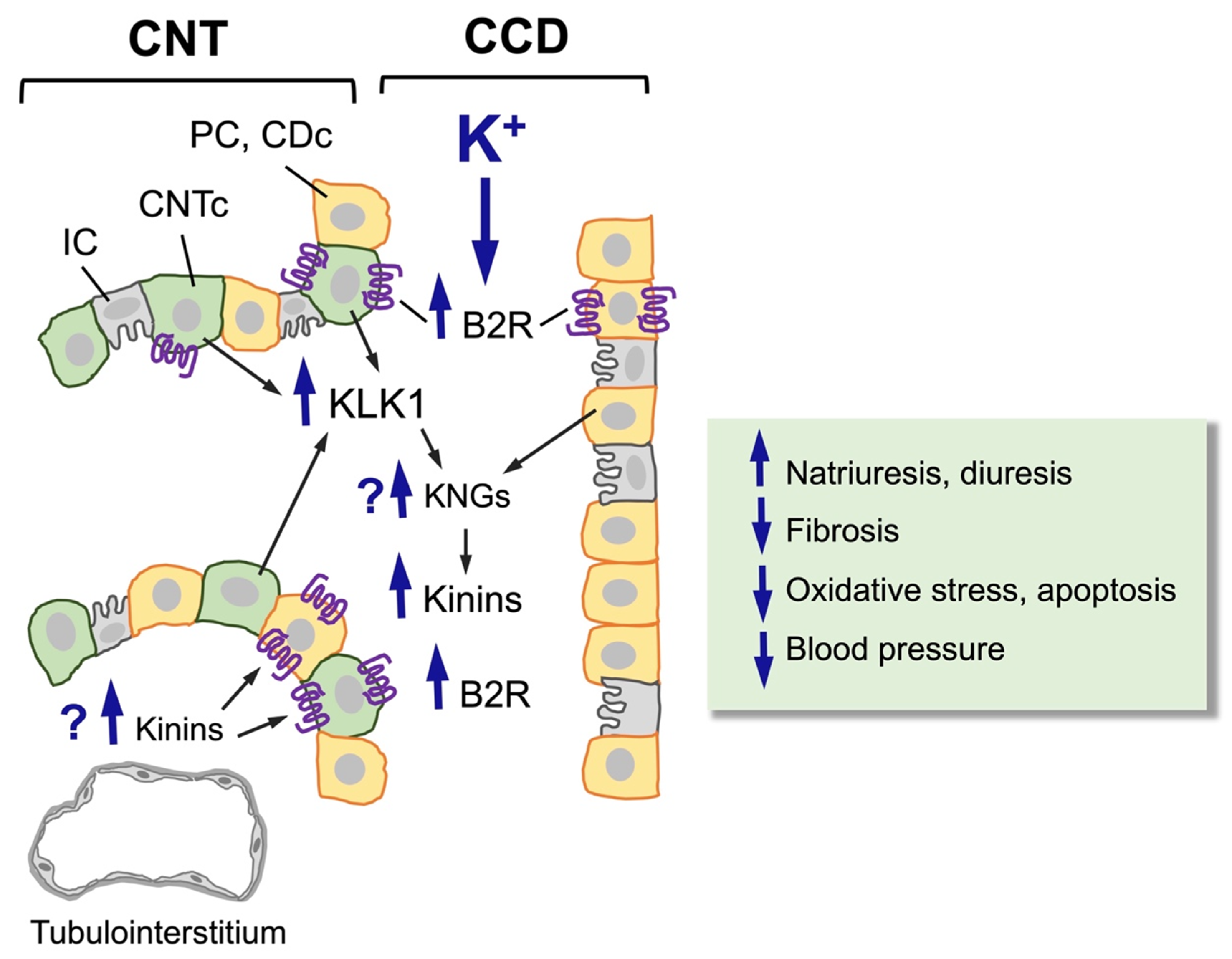

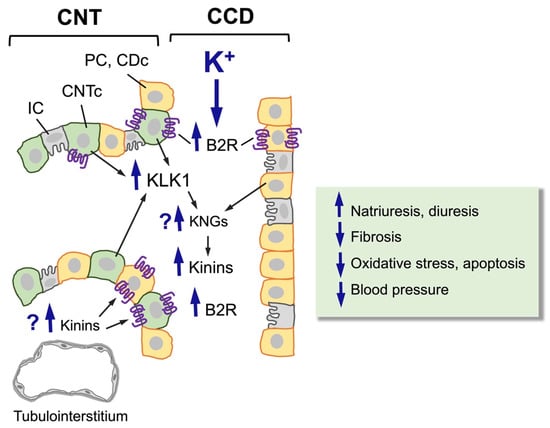

The impact of potassium administration in the diet and its stimulating effect on kallikrein synthesis and kinin B2R expression is well-documented (Figure 2). This non-pharmacological intervention has demonstrated efficacy in experimental settings, as evidenced by its ability to enhance system function [34,36,126].

Figure 2.

Effect of a high-potassium diet on the distal nephron (CNT-CCD). A high-potassium diet induces hypertrophy and hyperplasia of CNTc (pale green cells, KLK1-producing cells) and CDc/PC (orange cells, kininogen-producing cells), upregulating the synthesis and secretion of renal kallikrein (KLK1) by CNTc and the expression of the kinin B2 receptor (B2R) in CNTc and CDc/PC. So far, it is not known whether a high-potassium diet also increases the synthesis and/or release of renal kininogens or the levels of kinins in the renal interstitium. Upregulation of the kinin system induced by a high-potassium diet increases urinary kinin levels, natriuresis, and diuresis and reduces fibrosis, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and blood pressure.

Notably, potassium is actively secreted via ROMK by the connecting tubule cell, which is the site where renal kallikrein (KLK1) is synthesized and secreted [127]. The release of kallikrein into the tubule lumen and interstitium by this cell enables its duality, allowing it to concurrently contribute to the regulation of potassium and the production of kinins [128]. Collecting duct cells, which are involved in potassium excretion, are also the source of kininogen production. However, there is a paucity of studies that have examined the levels of renal kininogen in response to a high-potassium diet.

The administration of potassium has been observed to stimulate kallikrein secretion [129], a process that is accompanied by hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the cells that produce it. This includes hypertrophy of the Golgi apparatus and rough endoplasmic reticulum, as well as an increased number of kallikrein-containing secretory vesicles. These observations suggest that the increase in excretion is due to an increase in enzyme synthesis [126]. A diet with a high potassium content has been demonstrated to increase renal kallikrein mRNA expression by 2.7 times, urinary kallikrein excretion by up to 70%, and kinin B2R density in the kidney by 40% [130]. High potassium intake has been demonstrated to stimulate renal kallikrein synthesis via two predominant mechanisms: one that is aldosterone dependent and involves protein synthesis, and another that is rapid and aldosterone independent. In the initial pathway, potassium ions act as a stimulant, prompting the adrenal cortex to secrete aldosterone. This hormone subsequently binds to receptors present on the connecting tubule cell, thereby activating transcription genes that enhance kallikrein synthesis. In the second pathway, an excess of potassium causes a depolarization of the membranes of the connecting tubule cells. This depolarization leads to a calcium influx, which in turn stimulates the secretion of kallikrein [131]. Furthermore, given its classification as a G-protein-coupled receptor, B2R is susceptible to activation by an increase in potassium, which results in alterations to cell membrane polarization [132]. A body of research has demonstrated that the inclusion of potassium salts in the diet can lead to an increase in kallikrein excretion and a concomitant reduction in blood pressure levels [133,134]. Other researchers have observed a decrease in renal tissue injury; however, this phenomenon is not associated with the antihypertensive effect observed in spontaneously hypertensive rats [135].

In consideration of the aforementioned findings, a hypothesis can be formulated positing that stimulation of SKK by a potassium-rich diet may result in a renoprotective effect (Table 1).

Our group has investigated the effects of a potassium-rich diet on animal models of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. The results of these experiments demonstrate that the administration of a potassium-rich diet in the period before and during nephrotoxic injury, along with increasing renal kallikrein expression and production, reduces oxidative stress, apoptosis, and the expression of biomarkers of acute kidney injury [136].

Table 1.

Activation of the kallikrein kinin system and the B2 kinin receptor can induce renal protection. Experimental evidence.

Table 1.

Activation of the kallikrein kinin system and the B2 kinin receptor can induce renal protection. Experimental evidence.

| Experimental Model | Intervention | Renoprotective Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Proximal Tubular Cells in Culture Exposed to Albumin | Albumin Exposure + Bradykinin Administration | Reduction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition Reduced production of TGFβ-1 | [137] |

| Dahl rats salt sensitive | Administration of purified kallikrein | Reduced proteinuria Improved kidney function (effects deleted by Icatibant) | [69,71] |

| Nephrectomy 5/6 in rats | Transfection of the kallikrein gene | Attenuation of hypertension Albuminuria reduction Reduction of renal fibrosis | [72] |

| Dahl rats salt sensitive | Transfection of the kallikrein gene | Attenuation of hypertension Albuminuria reduction Reduction of renal fibrosis TGFβ-1 reduction and oxidative stress | [73,74,75] |

| Transgenic mice | Overexpression of B2 kinin receptor | Tendency to hypotension Enhanced renal function (effects deleted by icatibant) | [76] |

| Model of gentamicin acute kidney injury in rats | Administration of purified kallikrein | Reduction of pro-inflammatory mediators Reduction of oxidative stress and apoptosis | [82,84] |

| Diabetic mice | Tissue kallikrein knockout | Aggravation of diabetic nephropathy | [119] |

| Model of proteinuria due to albumin overload in rats | High potassium diet | Increased production and expression of renal kallikrein Increased kinin B2R expression Reduction of Renal Fibrosis Reduction of TGF-β expression (Effects deleted by icatibant) | [137] |

| Cisplatin Model of Acute Kidney Injury | High potassium diet | Increased renal kallikrein production and expression Reduction of apoptosis Reduction of oxidative stress KIM-1 expression reduction | [136] |

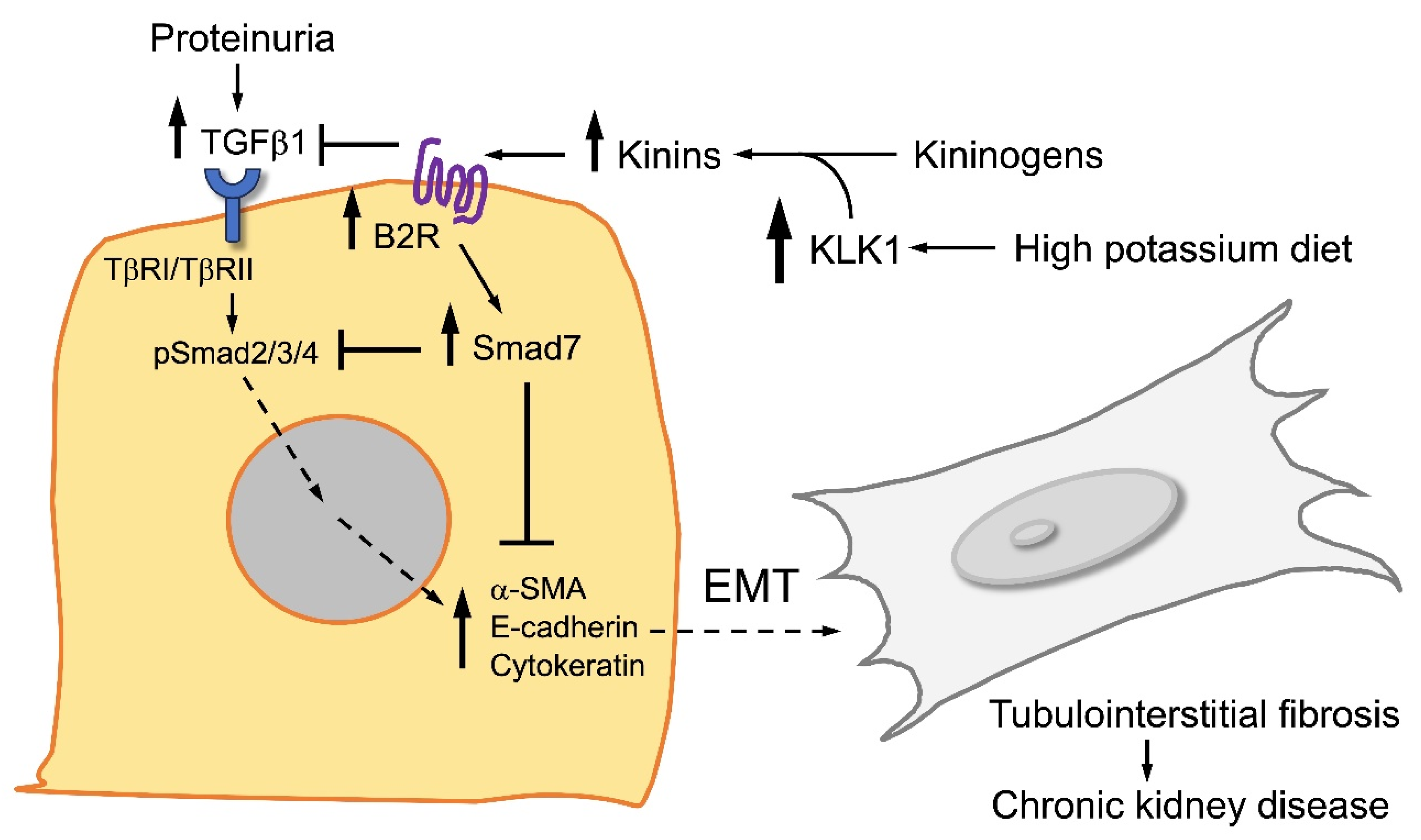

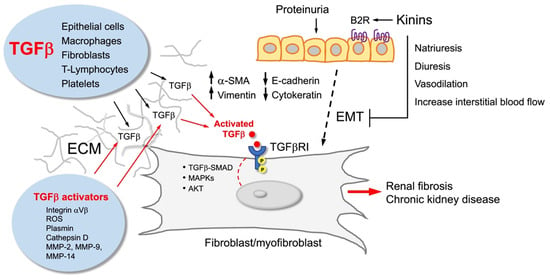

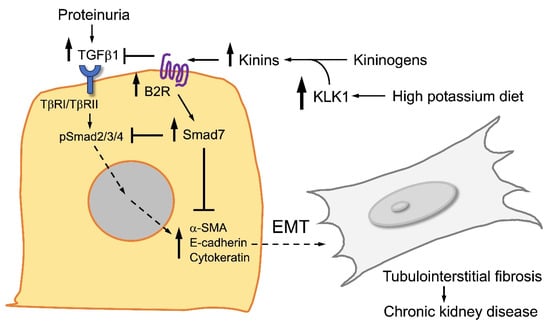

A series of experimental investigations were conducted in our laboratory during the induction stage of the proteinuria damage model. These investigations confirmed that potassium chloride exerts a stimulatory effect on renal kallikrein, manifesting in both tissue and urinary activity. The stimulatory effect was accompanied by a hypotensive effect [34]. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that a potassium-rich diet can significantly reduce the salt sensitivity observed after tubulointerstitial damage [36]. Utilizing this animal model, we were able to induce significant tubulointerstitial damage, encompassing the components of the KKS located in this area. In an initial approach, during the acute phase of overload proteinuria, it was observed that potassium induced a significant increase in both urinary activity and renal kallikrein expression, associated with a significant reduction in blood pressure These findings were made in a second series of experiments, utilizing the same animal model and a high salt diet. In the course of these experiments, a decrease in renal TGF-β mRNA and protein levels was observed in comparison with rats that did not receive potassium. The involvement of the kinin B2R was substantiated by the observation that all beneficial effects were abrogated in the presence of a kinin B2R antagonist. Concurrent in vitro experiments utilizing the HK-2 proximal tubule cell line demonstrated that the administration of bradykinin to tubular cells resulted in a reduction in EMT and albumin-induced production of TGF-β. The effects produced by bradykinin were counteracted by pretreatment with a kinin B2R antagonist. These experiments not only provide further evidence to support the hypothesis that the kinin pathway plays a pathogenic role in salt sensitivity. They also provide evidence of the pathways role as a renoprotective, antifibrotic paracrine system that modulates renal levels of TGF-β [36]. To support this theory, a study was conducted to compare the effects of potassium-rich diets on proteinuria induction in animals. The experimental animals were pretreated with a potassium-rich diet and then exposed to intraperitoneal albumin overload, which is a well-established method of inducing proteinuria. The control animals did not receive a high-potassium diet prior to the protein challenge. The high potassium group exhibited a reduction of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, diminished renal expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin and vimentin, reduced Smad3 phosphorylation, and augmented Smad7. These effects that were reversed by the kinin B2R antagonist HOE140, administered during the overload protein phase (Figure 3). In vitro experiments, conducted on the HK-2 cell line, revealed that elevated concentrations of albumin resulted in the expression of mesenchymal biomarkers, concomitant with augmented levels of TGF-β1 mRNA and its functionally active peptide, TGF-β1. We demonstrated that pretreatment of the cells with bradykinin inhibited the albumin-induced changes, thereby reducing alpha-smooth muscle actin and vimentin and recovering cytokeratin. This was accompanied by an increase in Smad7 levels and a decrease in type II TGF-β1 receptor, TGF-β1 mRNA, and its active fragment. The protective changes produced by bradykinin in vitro were blocked by the HOE140 antagonist [137] (Figure 4).

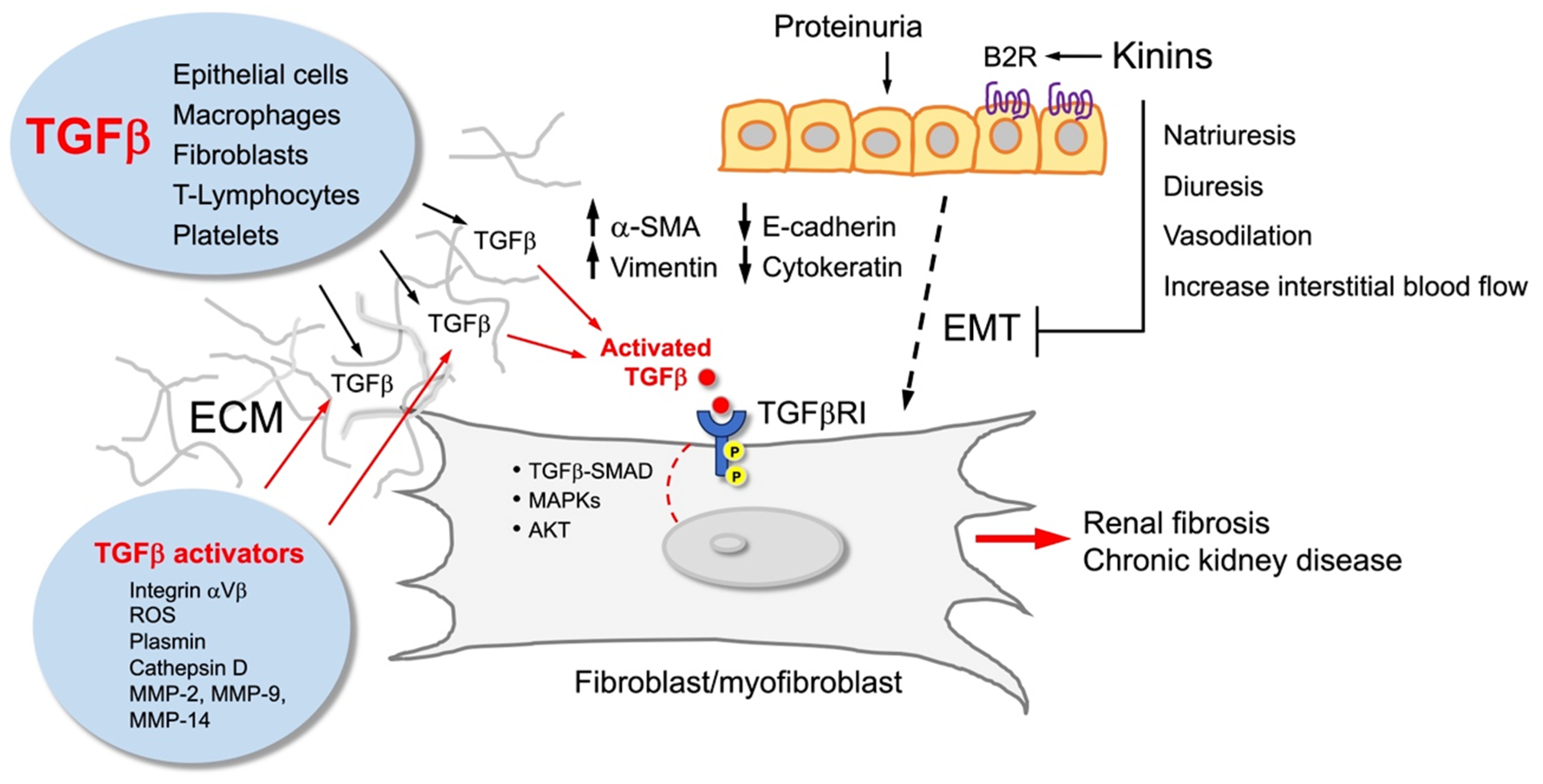

Figure 3.

Kinins and the kinin B2 receptor (B2R) counterbalance the effect of TGFbeta (TGFβ). TGFβ is produced by various types of cells that secrete it to the extracellular matrix (ECM), where it is activated to stimulate fibroblasts/myofibroblasts that accumulate in the tubulointerstitium and promote renal fibrosis. These cells may have different origins, including epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) from damaged tubular cells that acquire a new cellular phenotype characterized by high vimentin and alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) content. Kinins, through activation of the kinin B2R, reduce EMT, myofibroblast formation, and renal fibrosis.

Figure 4.

Major signaling routes activated by TGFbeta (TGFβ) and kinins in renal tubular cells. TGFβ activates the Smad2/3/4 signaling pathway that favors epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), myofibroblast differentiation, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. On the contrary, kinins and activation of the kinin B2 receptor (B2R) trigger the Smad7 pathway that reduces EMT and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. A high-potassium diet upregulates the kinin system, enhancing the antifibrotic activity of renal kinins.

Of particular interest was the demonstration of the hypotensive effect achieved by administering potassium chloride, which stimulated kallikrein production and reduced blood pressure both during the induction of damage and during the period of salt sensitivity in the animal model of protein overload. It is well established that the effect of potassium is not limited to the increase of kallikrein levels since it also augments the expression of the kinin B2R. It has been demonstrated that the latter is the most effective effector of vasoactive functions [129,130].

8. Human Evidences

The evolution of the human diet can provide insight into the significance of adequate potassium intake. During the Paleolithic era, early humans consumed fruits and vegetables, which provided low amounts of sodium (690 mg/day) and high amounts of potassium (11 g/day) [138]. Given the ongoing processes of population growth, agricultural development, the imperative to preserve food, shifts in dietary habits, the contemporary human population consumes a minimum of 5 g of sodium per day (equivalent to 8 g of common salt) and a mere 2.5 g of potassium [139]. The established link between sodium chloride intake and hypertension, along with its associated consequences, is a well-documented phenomenon [140]. The clinical manifestation of blood pressure fluctuations in response to alterations in salt intake has been aptly designated as “salt sensitivity” [141]. Consequently, research has been conducted to investigate the potential beneficial role of potassium intake on salt sensitivity [142], and randomized studies have demonstrated the hypotensive effect of a potassium-rich diet in the general population, with a more pronounced effect observed in hypertensive individuals [143]. This phenomenon is achieved through a natriuretic effect that is independent of aldosterone (and occurs prior to its secretion). This effect is mediated by acute dephosphorylation of NCC, the sodium-chloride cotransporter, in the distal tubule [144]. Many authors suggest that the relationship between potassium and sodium in the diet is more significant than either of them individually. Higher sodium and lower potassium intakes, as measured in multiple 24-h urine samples, have been associated in a dose-response manner with a higher cardiovascular risk [145]. Conversely, both higher potassium and a lower sodium-to-potassium ratio have been linked to a diminished risk of cardiovascular disease [146].

Evidence from human studies suggests a potential link between a diet rich in potassium, as indicated by a regular intake of fruits and vegetables and moderate sodium intake, and renal protection. Nonetheless, the findings are not yet consistent and further investigation is required to determine their applicability on an individual basis (Table 2). The majority of observational population cohort studies that evaluated renal protection estimated potassium intake through 24-h urinary excretion. One of these studies was conducted with individuals without CKD from the UK Biobank cohort. This study demonstrated that elevated potassium intake, when adjusted for confounding factors such as blood pressure and sodium intake, was associated with a lower risk of developing incident CKD at 11.9 years of follow-up [147]. An additional analysis, derived from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, demonstrated renal protection over a 20-year period [148]. Similar findings were observed after 11 years of follow-up in type 2 diabetics with normal renal function, where higher urinary potassium excretion was associated with a slower decline in renal function [149]. In a similar vein, low potassium intake has been shown to be associated with heightened incidence of CKD over a 10-year period in in 5315 non-CKD individuals as part of the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease (PREVEND) Study [150].

Table 2.

Human studies associating the amount of potassium in the diet with the incidence and progression of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD).

In patients with established CKD who are not on dialysis, the results are contradictory. In the Korean Cohort Study for Outcome in Patients with CKD, urinary potassium excretion was inversely associated with a decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, suggesting that higher potassium intake could be associated with better functional outcomes [155], a concept reinforced in a recent publication showing that low potassium intake is associated with greater progression in patients with CKD [156].

However, these results have not been consistent with others, who have observed neutral [157,158] or even detrimental results [153]. This suggests that the effect may be more relevant in earlier stages. It is conceivable that higher potassium intake could be associated with better dietary habits, including increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, reduced sodium intake, and a lower incidence of hypertension. This association, however, remains speculative given the observational study design, which precludes the establishment of causality.

The clinical trial “Renoprotective Effects of Potassium Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease” (NCT03253172) [159], which aims to study the renoprotective effect of potassium supplementation in patients with stage 3b or 4 CKD. It is currently in development and should be completed in May 2026.

There is reasonable doubt regarding the administration of potassium-rich diets to individuals with chronic kidney disease, considering that potassium is almost exclusively excreted by the kidney (80 to 90% of the daily intake).

It is noteworthy that in patients with CKD, hyperkalemia is uncommon when GFR is above 60 mL/1.73 m2, but its prevalence increases as GFR decreases [160,161]. Potassium homeostasis is impaired in patients with CKD due to alterations in physiological mechanisms and the use of agents that modulate the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) to slow CKD progression and reduce cardiovascular risk.

As GFR declines below 30 mL/1.73 m2, hyperkalemia gradually develops through several mechanisms, including a decrease in distal sodium delivery (as occurs in decompensated heart failure), a reduction in mineralocorticoid activity (common in diabetes with hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism or due to RAAS inhibitor therapy), and tubular dysfunction associated with the tubulointerstitial condition [162].

As indicated above, the primary challenge to the large-scale implementation of potassium-rich diets in established CKD contexts is the concomitant utilization of the most prevalent renoprotective approach: renin-angiotensin aldosterone system inhibition, encompassing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and nonsteroidal or steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [163]. Concurrently, a substantial body of research has documented a multitude of deleterious cardiorenal consequences associated with the reduction or cessation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition in patients with CKD [164,165].

However, there is physiological evidence that a high-potassium diet induces renal adaptations that allow for better tolerance of an acute load of this ion, through increased excretion and tubular handling. Classic experimental studies demonstrate that animals fed a high-potassium diet exhibit an augmented capacity for potassium excretion and survival following acute loads that would prove lethal to control animals. This phenomenon is achieved through a process known as potassium tolerance. This process encompasses both renal adaptation and an augmentation in cellular potassium uptake. This augmentation is referred to as extrarenal potassium adaptation [166].

Preliminary results from NCT03253172 demonstrate that in patients with CKD stage G3b-4, increasing dietary potassium intake with potassium chloride supplementation elevates plasma potassium by only 0.4 mmol/L (it is noteworthy that 83% of subjects were using RAAS blockade). However, it is imperative to acknowledge that this intervention may potentially lead to hyperkalemia in elderly patients or those with elevated baseline plasma potassium levels. It is of great importance that prolonged studies be carried out to ascertain whether cardiorenal protection holds greater significance than the risk of hyperkalemia [167].

Hyperkalemia, induced by a potassium-rich diet, could be counteracted by the concomitant use of SGLT2i. The value of glyfozines, when added to RAS blockade, is now recognized. These substances enhance renal and cardiovascular protective effects and reduce the hyperkalemic effect [168] due to their kaliuretic effect, which is induced by increased distal sodium availability. A notable absence of data exists concerning the effects of glyfozines on KKS activity.

Consequently, a novel paradox has emerged: while the conventional recommendation has been a dietary restriction of potassium with the aim of preventing hyperkalemia, emerging evidence suggests that a more liberal intake of potassium may offer potential benefits, particularly in patients with early CKD. This has prompted a paradigm shift towards a more individualized approach to the management of hyperkalemia in CKD [169].

Preliminary findings indicate that a promising approach to address this issue may involve the promotion of potassium-rich diets in the early stages of CKD. This approach has the potential to establish a preconditioning state that would enable the sustained use of potassium-rich diets and maintain RAS blockade in more advanced stages of CKD.

9. Concluding Remarks

The hypothesis that the stimulation and preservation of the renal KKS can act as a strategy for renal protection is a rational approach, given the established mechanisms by which an active and healthy KKS system can mitigate renal damage. Despite the pharmacological potential of drugs that increase the activity of the system, a non-pharmacological approach is a viable prospect. This approach involves the stimulation of kallikrein synthesis, kinin production, and kinin B2R expression through a potassium-rich diet, which has also been demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular risk. A renal environment abundant in kinins, derived from a potassium-rich diet, has the potential to enhance an individual’s capacity to effectively manage the diverse nephrotoxic challenges that arise throughout the course of their lives. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that this could decelerate the progression to advanced kidney damage once the injury has been established. This straightforward approach, when implemented in conjunction with a reduction in sodium intake, can be accomplished through comprehensive nutritional education and adopted without compromising quality of life. Indeed, it can be incorporated into a patient’s diet at an early stage of kidney disease and maintained until renal function and potassium excretion allow it, with a high cost-benefit ratio and therefore scalable to a large scale.

Author Contributions

C.D.F. and L.A. writing—original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Kanti Bhoola, in recognition of his invaluable contributions to science and his enduring impact on our field. The present manuscript was produced as part of the activities of the International Society of Nephrology’s Renal Training Center at the Universidad Austral de Chile in Valdivia. During the preparation of this review, ChatGPT 5 was used for the purposes of creating the Graphical Abstract. We have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thurlow, J.S.; Joshi, M.; Yan, G.; Norris, K.C.; Agodoa, L.Y.; Yuan, C.M.; Nee, R. Global epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease and disparities in kidney replacement therapy. Am. J. Nephrol. 2021, 52, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K.P.; Morgenstern, H.; Saran, R.; Herman, W.H.; Robinson, B.M. Projecting esrd incidence and prevalence in the united states through 2030. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieppati, A.; Remuzzi, G. The june 2003 barry m. Brenner comgan lecture. The future of renoprotection: Frustration and promises. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoola, K.D.; Figueroa, C.D.; Worthy, K. Bioregulation of kinins: Kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol. Rev. 1992, 44, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, A.A. Protein restriction reduces transforming growth factor-beta and interstitial fibrosis in nephrotic syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 266, F884–F893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remuzzi, G. Nephropathic nature of proteinuria. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1999, 8, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, A.A. Expression of genes that promote renal interstitial fibrosis in rats with proteinuria. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1996, 54, S49–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, A.A. Molecular insights into renal interstitial fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996, 7, 2495–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, T.; Cutillo, F.; Zoja, C.; Broggini, M.; Remuzzi, G. Tubulo-interstitial lesions mediate renal damage in adriamycin glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 1986, 30, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo, R.; Gómez-Garre, D.; Soto, K.; Marrón, B.; Blanco, J.; Gazapo, R.M.; Plaza, J.J.; Egido, J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme is upregulated in the proximal tubules of rats with intense proteinuria. Hypertension 1999, 33, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Garre, D.; Largo, R.; Tejera, N.; Fortes, J.; Manzarbeitia, F.; Egido, J. Activation of nf-kappab in tubular epithelial cells of rats with intense proteinuria: Role of angiotensin ii and endothelin-1. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vio, C.P.; Loyola, S.; Velarde, V. Localization of components of the kallikrein-kinin system in the kidney: Relation to renal function. State of the art lecture. Hypertension 1992, 19, II10–II16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vío, C.P.; Figueroa, C.D. Subcellular localization of renal kallikrein by ultrastructural immunocytochemistry. Kidney Int. 1985, 28, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, C.D.; MacIver, A.G.; Mackenzie, J.C.; Bhoola, K.D. Localisation of immunoreactive kininogen and tissue kallikrein in the human nephron. Histochemistry 1988, 89, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragy, H.M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Jaffa, A.A.; Mayfield, R.; Margolius, H.S. Rat renal interstitial bradykinin, prostaglandin e2, and cyclic guanosine 3″,5″-monophosphate. Effects of altered sodium intake. Hypertension 1994, 23, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, F.; Bachvarov, D.R. Kinin receptors. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 1998, 16, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb-Lundberg, L.M.; Marceau, F.; Müller-Esterl, W.; Pettibone, D.J.; Zuraw, B.L. International union of pharmacology. Xlv. Classification of the kinin receptor family: From molecular mechanisms to pathophysiological consequences. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 27–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huart, A.; Klein, J.; Gonzalez, J.; Buffin-Meyer, B.; Neau, E.; Delage, C.; Calise, D.; Ribes, D.; Schanstra, J.P.; Bascands, J.L. Kinin b1 receptor antagonism is equally efficient as angiotensin receptor 1 antagonism in reducing renal fibrosis in experimental obstructive nephropathy, but is not additive. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Gonzalez, J.; Duchene, J.; Esposito, L.; Pradère, J.P.; Neau, E.; Delage, C.; Calise, D.; Ahluwalia, A.; Carayon, P.; et al. Delayed blockade of the kinin b1 receptor reduces renal inflammation and fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H.; Campanholle, G.; Cenedeze, M.A.; Feitoza, C.Q.; Gonçalves, G.M.; Landgraf, R.G.; Jancar, S.; Pesquero, J.B.; Pacheco-Silva, A.; Câmara, N.O. Bradykinin [corrected] b1 receptor antagonism is beneficial in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.H.; Cenedeze, M.A.; Campanholle, G.; Malheiros, D.M.; Torres, H.A.; Pesquero, J.B.; Pacheco-Silva, A.; Câmara, N.O. Deletion of bradykinin b1 receptor reduces renal fibrosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basuli, D.; Parekh, R.U.; White, A.; Thayyil, A.; Sriramula, S. Kinin b1 receptor mediates renal injury and remodeling in hypertension. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 780834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrela, G.R.; Santos, R.B.; Budu, A.; de Arruda, A.C.; Barrera-Chimal, J.; Araújo, R.C. Kinin b1 receptor antagonism prevents acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease transition in renal ischemia-reperfusion by increasing the m2 macrophages population in c57bl6j mice. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, C.D.; Gonzalez, C.B.; Grigoriev, S.; Alla, S.A.A.; Haasemann, M.; Jarnagin, K.; Müller-Esterl, W. Probing for the bradykinin b2 receptor in rat kidney by anti-peptide and anti-ligand antibodies. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1995, 43, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.; Hock, F.J.; Albus, U.; Linz, W.; Alpermann, H.G.; Anagnostopoulos, H.; Henk, S.; Breipohl, G.; König, W.; Knolle, J. Hoe 140 a new potent and long acting bradykinin-antagonist: In vivo studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 102, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange, M.; Petersen, R.S.; Fijen, L.M.; Cohn, D.M. Long-term prophylactic treatment with deucrictibant for angioedema due to acquired c1-inhibitor deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 156, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katori, M.; Majima, M. The renal kallikrein-kinin system: Its role as a safety valve for excess sodium intake, and its attenuation as a possible etiologic factor in salt-sensitive hypertension. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2003, 40, 43–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, R.J.; Michael, A.F. Urinary kallikrein in experimental renal disease. Lab. Investig. 1976, 34, 616–622. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, C.; Bellini, C.; Carlomagno, A.; Perrone, A.; Santucci, A. Urinary kallikrein and salt sensitivity in essential hypertensive males. Kidney Int. 1994, 46, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.; Gimenez, M.I.; Ramos, F.; Baglivo, H.; Ramirez, A.J. Non-modulating hypertension: Evidence for the involvement of kallikrein/kinin activity associated with overactivity of the renin-angiotensin system. Successful blood pressure control during long-term na+ restriction. J. Hypertens. 1996, 14, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolius, H.S. Theodore cooper memorial lecture. Kallikreins and kinins. Some unanswered questions about system characteristics and roles in human disease. Hypertension 1995, 26, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Chao, L. Kallikrein-kinin in stroke, cardiovascular and renal disease. Exp. Physiol. 2005, 90, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiles, L.G.; Figueroa, C.D.; Mezzano, S.A. Renal kallikrein-kinin system damage and salt sensitivity: Insights from experimental models. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2003, 64, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardiles, L.G.; Loyola, F.; Ehrenfeld, P.; Burgos, M.E.; Flores, C.A.; Valderrama, G.; Caorsi, I.; Egido, J.; Mezzano, S.A.; Figueroa, C.D. Modulation of renal kallikrein by a high potassium diet in rats with intense proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardiles, L.G.; Ehrenfeld, P.; Quiroz, Y.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; Mezzano, S.; Figueroa, C.D. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on kallikrein expression in the kidney of 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2002, 25, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardiles, L.; Cardenas, A.; Burgos, M.E.; Droguett, A.; Ehrenfeld, P.; Carpio, D.; Mezzano, S.; Figueroa, C.D. Antihypertensive and renoprotective effect of the kinin pathway activated by potassium in a model of salt sensitivity following overload proteinuria. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2013, 304, F1399–F1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.G. Urinary enzymes, nephrotoxicity and renal disease. Toxicology 1982, 23, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, S.; Naidoo, S.; Ramsaroop, R.; Moodley, D.; Bhoola, K. Tissue kallikrein and kinins in renal disease. Immunopharmacology 1999, 44, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bowden, D.W.; Spray, B.J.; Rich, S.S.; Freedman, B.I. Identification of human plasma kallikrein gene polymorphisms and evaluation of their role in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 1998, 31, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozwiak, L.; Drop, A.; Buraczynska, K.; Ksiazek, P.; Mierzicki, P.; Buraczynska, M. Association of the human bradykinin b2 receptor gene with chronic renal failure. Mol. Diagn. 2004, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Pons, H.; Quiroz, Y.; Gordon, K.; Rincón, J.; Chávez, M.; Parra, G.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; Gómez-Garre, D.; Largo, R.; et al. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin ii exposure. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; El-Dahr, S.S. Cross-talk of the renin-angiotensin and kallikrein-kinin systems. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, A.; Mackenzie, H.S.; Lacy, E.R.; Hutchison, F.N.; Fitzgibbon, W.R.; Ploth, D.W. Effects of chronic treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor antagonist in two-kidney, one-clip hypertensive rats. Kidney Int. 1995, 47, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, K.; Igari, T.; Nanba, S.; Ishii, M. Long-term effects of delapril on renal function and urinary excretion of kallikrein, prostaglandin e2, and thromboxane b2 in hypertensive patients. Am. J. Hypertens. 1991, 4, 52S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, H.J.; Glänzer, K.; Meyer-Lehnert, H.; Mohaupt, M.; Predel, H.G. Kinin- and non-kinin-mediated interactions of converting enzyme inhibitors with vasoactive hormones. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1990, 15, S91–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, F.N.; Cui, X.; Webster, S.K. The antiproteinuric action of angiotensin-converting enzyme is dependent on kinin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1995, 6, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggenenti, P.; Perna, A.G.; Gherardi, F.; Benini, R.; Remuzzi, G. Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy patients on long-term ramipril: Rein follow-up trial. Gruppo italiano di studi epidemiologici in nefrologia (gisen). Ramipril efficacy in nephropathy. Lancet 1998, 352, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluczyk, I.Z.; Patel, S.R.; Harris, K.P. The role of bradykinin in the antifibrotic actions of perindoprilat on human mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluczyk, I.Z.; Tan, E.K.; Lodwick, D.; Harris, K. Kallikrein gene ‘knock-down’ by small interfering rna transfection induces a profibrotic phenotype in rat mesangial cells. J. Hypertens. 2008, 26, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdös, E.G. Angiotensin i converting enzyme and the changes in our concepts through the years. Lewis k. Dahl memorial lecture. Hypertension 1990, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, L.J.; Gainer, J.V.; Vaughan, D.E.; Brown, N.J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism modulates the human in vivo metabolism of bradykinin. Circulation 2000, 102, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marre, M.; Bouhanick, B.; Berrut, G.; Gallois, Y.; Le Jeune, J.J.; Chatellier, G.; Menard, J.; Alhenc-Gelas, F. Renal changes on hyperglycemia and angiotensin-converting enzyme in type 1 diabetes. Hypertension 1999, 33, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desposito, D.; Waeckel, L.; Potier, L.; Richer, C.; Roussel, R.; Bouby, N.; Alhenc-Gelas, F. Kallikrein(k1)-kinin-kininase (ace) and end-organ damage in ischemia and diabetes: Therapeutic implications. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waeckel, L.; Potier, L.; Richer, C.; Roussel, R.; Bouby, N.; Alhenc-Gelas, F. Pathophysiology of genetic deficiency in tissue kallikrein activity in mouse and man. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 110, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoki, M.; Smithies, O. The kallikrein-kinin system in health and in diseases of the kidney. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Sleight, P.; Pogue, J.; Bosch, J.; Davies, R.; Dagenais, G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhenc-Gelas, F.; Bouby, N.; Richer, C.; Potier, L.; Roussel, R.; Marre, M. Kinins as therapeutic agents in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 2654–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaleb, N.E.; Yang, X.P.; Carretero, O.A. The kallikrein-kinin system as a regulator of cardiovascular and renal function. Compr. Physiol. 2011, 1, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, J.-P.; Bouby, N.; Richer-Giudicelli, C.; Alhenc-Gelas, F. Kinins and kinin receptors in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzuki, M.; Yasujima, M.; Kanazawa, M.; Yoshida, K.; Sato, T.; Abe, K. Do kinins mediate cardioprotective and renoprotective effects of cilazapril in spontaneously hypertensive rats with renal ablation? Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. Suppl. 1995, 22, S357–S359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaya, S.; Hilgers, R.H.; Meneton, P.; Dong, Y.; Bloch-Faure, M.; Inagami, T.; Alhenc-Gelas, F.; Lévy, B.I.; Boulanger, C.M. Flow-dependent dilation mediated by endogenous kinins requires angiotensin at2 receptors. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messadi-Laribi, E.; Griol-Charhbili, V.; Pizard, A.; Vincent, M.P.; Heudes, D.; Meneton, P.; Alhenc-Gelas, F.; Richer, C. Tissue kallikrein is involved in the cardioprotective effect of at1-receptor blockade in acute myocardial ischemia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 323, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.H.; Yang, X.P.; Sharov, V.G.; Nass, O.; Sabbah, H.N.; Peterson, E.; Carretero, O.A. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii type 1 receptor antagonists in rats with heart failure. Role of kinins and angiotensin ii type 2 receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 1926–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadir, P.M.; Periasamy, A.; Carey, R.M.; Siragy, H.M. Angiotensin ii type 2 receptor-bradykinin b2 receptor functional heterodimerization. Hypertension 2006, 48, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Nair, A.P.; Misra, A.; Scott, C.Z.; Mahar, J.H.; Fedson, S. Neprilysin inhibitors in heart failure: The science, mechanism of action, clinical studies, and unanswered questions. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koid, S.S.; Ziogas, J.; Campbell, D.J. Aliskiren reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by a bradykinin b2 receptor- and angiotensin at2 receptor-mediated mechanism. Hypertension 2014, 63, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeddu, P.; Varoni, M.V.; Palomba, D.; Emanueli, C.; Demontis, M.P.; Glorioso, N.; Dessì-Fulgheri, P.; Sarzani, R.; Anania, V. Cardiovascular phenotype of a mouse strain with disruption of bradykinin b2-receptor gene. Circulation 1997, 96, 3570–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milia, A.F.; Gross, V.; Plehm, R.; De Silva, J.A.; Bader, M.; Luft, F.C. Normal blood pressure and renal function in mice lacking the bradykinin b(2) receptor. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, Y.; Hirawa, N.; Numabe, A.; Kawabata, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Gomi, T.; Gotoh, A.; Omata, M. Long-term infusion of kallikrein attenuates renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 1997, 10, 83S–88S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirawa, N.; Uehara, Y.; Kawabata, Y.; Numabe, A.; Gomi, T.; Ikeda, T.; Suzuki, T.; Goto, A.; Toyo-oka, T.; Omata, M. Long-term inhibition of renin-angiotensin system sustains memory function in aged dahl rats. Hypertension 1999, 34, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirawa, N.; Uehara, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kawabata, Y.; Numabe, A.; Gomi, T.; Lkeda, T.; Kizuki, K.; Omata, M. Regression of glomerular injury by kallikrein infusion in dahl salt-sensitive rats is a bradykinin b2-receptor-mediated event. Nephron 1999, 81, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, W.C.; Yoshida, H.; Agata, J.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Human tissue kallikrein gene delivery attenuates hypertension, renal injury, and cardiac remodeling in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Lin, K.F.; Chao, L. Adenovirus-mediated kallikrein gene delivery reverses salt-induced renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats. Kidney Int. 1998, 54, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Lin, K.F.; Chao, L. Human kallikrein gene delivery attenuates hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and renal injury in dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Bledsoe, G.; Kato, K.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Tissue kallikrein attenuates salt-induced renal fibrosis by inhibition of oxidative stress. Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yoshida, H.; Song, Q.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Enhanced renal function in bradykinin b(2) receptor transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2000, 278, F484–F491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.F.; Bledsoe, G.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Kallikrein gene transfer reduces renal fibrosis, hypertrophy, and proliferation in doca-salt hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2005, 289, F622–F631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, V.; Quiroz, Y.; Nava, M.; Pons, H.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B. Overload proteinuria is followed by salt-sensitive hypertension caused by renal infiltration of immune cells. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2002, 283, F1132–F1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.S.; Ahsan, N.; Taguchi, T. Role of apoptosis in fibrogenesis. Nephron 2002, 90, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Renal fibrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-De La Cruz, M.C.; Ruiz-Torres, P.; Alcamí, J.; Díez-Marqués, L.; Ortega-Velázquez, R.; Chen, S.; Rodríguez-Puyol, M.; Ziyadeh, F.N.; Rodríguez-Puyol, D. Hydrogen peroxide increases extracellular matrix mrna through tgf-beta in human mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, G.; Shen, B.; Yao, Y.Y.; Hagiwara, M.; Mizell, B.; Teuton, M.; Grass, D.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Role of tissue kallikrein in prevention and recovery of gentamicin-induced renal injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 102, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, Y.; Nishi, H.; Nangaku, M. Role of inflammation in progression of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical implications. Semin. Nephrol. 2023, 43, 151431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bledsoe, G.; Crickman, S.; Mao, J.; Xia, C.F.; Murakami, H.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Kallikrein/kinin protects against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoki, M.; Kizer, C.M.; Yi, X.; Takahashi, N.; Kim, H.S.; Bagnell, C.R.; Edgell, C.J.; Maeda, N.; Jennette, J.C.; Smithies, O. Senescence-associated phenotypes in akita diabetic mice are enhanced by absence of bradykinin b2 receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhr, F.; Lowry, J.; Zhang, Y.; Brovkovych, V.; Skidgel, R.A. Differential regulation of inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthase by kinin b1 and b2 receptors. Neuropeptides 2010, 44, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnakian, A.G.; Kaushal, G.P.; Shah, S.V. Apoptotic pathways of oxidative damage to renal tubular epithelial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002, 4, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Tsuji, T.; Yasuda, H.; Sun, Y.; Fujigaki, Y.; Hishida, A. The molecular mechanisms of the attenuation of cisplatin-induced acute renal failure by n-acetylcysteine in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Z.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhu, L.; Xu, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, F.R.; Cai, Z.N.; Shen, Y.L. COX-2 and HO-1 are involved in the delayed preconditioning elicited by bradykinin in rat hearts. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2007, 36, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.L.; Wang, H.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Yang, C.M. Reactive oxygen species-dependent c-fos/activator protein 1 induction upregulates heme oxygenase-1 expression by bradykinin in brain astrocytes. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2010, 13, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A. Nephrology forum: Apoptotic regulatory proteins in renal injury. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Cuadrado, S.G.; Lorz, C.; Egido, J. Apoptosis in renal diseases. Front. Biosci. 1996, 1, d30–d47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, G.L.; Yang, B.; Wagner, B.E.; Savill, J.; El Nahas, A.M. Cellular apoptosis and proliferation in experimental renal fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1998, 13, 2216–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukawa, K.; Kishino, M.; Goda, M.; Liang, X.M.; Kimura, A.; Tanaka, T.; Bai, T.; Owada-Makabe, K.; Tsubota, Y.; Ueyama, T.; et al. Stat6 deficiency inhibits tubulointerstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 15, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D. Roles of oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2004, 13, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, D.; Yin, H.; Dobrzynski, E.; Agata, J.; Yoshida, H.; Chao, J.; Chao, L. Kallikrein gene delivery improves serum glucose and lipid profiles and cardiac function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.A.; Harwood, S.; Varagunam, M.; Raftery, M.J.; Yaqoob, M.M. High glucose-induced oxidative stress causes apoptosis in proximal tubular epithelial cells and is mediated by multiple caspases. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, Y.; Bravo, J.; Herrera-Acosta, J.; Johnson, R.J.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B. Apoptosis and nfkappab activation are simultaneously induced in renal tubulointerstitium in experimental hypertension. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2003, 64, S27–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.; Gómez-Garre, D.; Largo, R.; Gallego-Delgado, J.; Tejera, N.; Catalán, M.P.; Ortiz, A.; Plaza, J.J.; Alonso, C.; Egido, J. Tight blood pressure control decreases apoptosis during renal damage. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.E.; Brunskill, N.J.; Harris, K.P.; Bailey, E.; Pringle, J.H.; Furness, P.N.; Walls, J. Proteinuria induces tubular cell turnover: A potential mechanism for tubular atrophy. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]