Abstract

Background/Objectives: Cephalosporins represent one of the most important classes of β-lactam antibiotics, widely used in clinical practice due to their broad-spectrum activity and favorable safety profile. As generations evolved, structural modifications were introduced to expand antimicrobial coverage and overcome β-lactamase resistance. This study aimed to analyze the drug-like properties of cephalosporins across different generations using molecular descriptors to identify structural and pharmacokinetic patterns influencing bioavailability and oral administration profiles. Methods: Thirty-eight cephalosporins representative of different generations were selected. Molecular data were obtained from PubChem, and SMILES were extracted and validated. Molecular descriptors (including MW, logP, TPSA, HBA, HBD, rotatable bonds, and global complexity indices) were calculated using the SwissADME and ChemDes platforms. Statistical analysis included ANOVA followed by post hoc tests, and principal component analysis (PCA). Results: A progressive increase in molecular weight, polarity, and TPSA was observed across generations, with fourth-generation cephalosporins showing significantly higher values compared to first-generation compounds (p < 0.0001). LogP decreased significantly in fourth-generation agents (p < 0.0001), reflecting increased polarity. PCA revealed that most compounds from generations 1–2 cluster in regions consistent with Lipinski’s and Veber’s rules, whereas fourth- and fifth generation - cephalosporins deviated substantially, prioritizing antimicrobial efficacy over oral bioavailability. Recurrent structural modifications such as oximes, tetrazoles, and aminothiazoles were identified, with increasing frequency in modern generations. Conclusions: The evolution of cephalosporins reflects a strategic shift toward enhanced antimicrobial potency and β-lactamase stability at the expense of oral bioavailability. Understanding these structural transitions provides valuable insights for rational drug design, aiming to balance antimicrobial effectiveness with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles essential for therapeutic success.

1. Introduction

Cephalosporins constitute one of the most extensively utilized antibiotic classes worldwide, owing to their broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, coupled with a favorable side effect profile [1]. Structurally, cephalosporins are β-lactam antimicrobials characterized by a β-lactam ring fused to a dihydro-2H-thiopyran ring, forming the 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA) core [2]. Chemical substitutions at the C3 and C7 positions of this nucleus confer structural diversity, directly influencing the antibacterial spectrum, β-lactamase resistance, and pharmacokinetic properties [2].

The origins of cephalosporins date back to 1945, when an antibiotic-producing Cephalosporium species was isolated in Sardinia [3]. Four years later, in Oxford, this strain was identified as producing several antibiotics, including cephalosporin C, which stood out for its stability against penicillinase (β-lactamase) degradation—a crucial characteristic given the challenges posed by penicillinase-producing Staphylococcus strains at the time [3]. The discovery of cephalosporin C in the 1950s paved the way for the development of hundreds of new cephalosporins, many of which were introduced into clinical practice to treat infections caused by penicillinase-producing pathogens such as S. aureus [4]. From the isolation of the cephalosporin C nucleus (7-ACA), the pharmaceutical industry synthesized thousands of derivatives, resulting in numerous compounds effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with low toxicity, significantly expanding treatment options [3]. Although early generations of cephalosporins were susceptible to hydrolysis by many β-lactamases that emerged after their introduction, some remain in use for mild-to-moderate infections [4].

Cephalosporins, like other β-lactam antibiotics, exert their bactericidal effect by inhibiting the final stages of peptidoglycan synthesis in the bacterial cell wall [4]. They acylate the transpeptidase site of membrane-bound penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which normally catalyze the transpeptidation and, in some species, carboxypeptidation reactions responsible for cross-linking peptidoglycan strands [5,6]. This irreversible acyl-enzyme complex blocks peptidoglycan cross-linking, leading to a mechanically weakened cell wall that becomes unable to withstand osmotic pressure, ultimately resulting in cell lysis during growth and division. Different cephalosporins display distinct affinities for individual PBPs in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, which contributes to differences in spectrum of activity and bactericidal profile [5].

Beginning in the 1960s, the molecular engineering of cephalosporins became an area of intense research and development, focusing on modifications to the 7-ACA core. Positions C3 (located on the dihydrothiazine ring) and C7 (on the β-lactam ring) are the primary sites of modification, as they allow the introduction of diverse side chains that alter drug properties. At position C7, substitutions modify the antibacterial spectrum, directly influencing the antibiotic’s affinity for penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs)—their primary targets—and the ability to penetrate through outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, which is critical for effective bactericidal action [1,7]. Modifications at position C3 significantly impact β-lactamase resistance by altering the reactivity of the β-lactam ring and, consequently, its susceptibility to enzymatic hydrolysis. Additionally, side chains at C3 are determinants of pharmacokinetic properties such as oral absorption capacity, half-life, and tissue diffusion capacity. For example, the lipophilic character conferred by substitutions at this position plays a fundamental role in drug penetration through biological barriers [2,8]. This sophisticated structural engineering was essential for the advancement of cephalosporin generations, enabling the overcoming of resistance challenges and optimization of clinical efficacy [4,9,10], while also profoundly altering the molecular characteristics of cephalosporins.

The development of these new drugs required the use of tools to aid in identifying compounds with physicochemical properties suitable for oral administration and favorable pharmacokinetics [11]. In this context, Lipinski’s Rule of Five, formulated in 1997, is one of the most widely employed criteria for evaluating drug-likeness and potential oral bioavailability of a molecule [12,13,14]. This rule postulates that for a compound to have good oral absorption, it should not violate more than one of the following parameters: molecular weight less than 500 Daltons, partition coefficient logP (octanol–water) not exceeding five, number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) not exceeding five, and number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) not exceeding 10 [12,13,14].

Complementarily, Veber’s Rule provides additional criteria for predicting oral bioavailability of drugs, based on properties such as molecular flexibility and surface polarity [13,14,15]. According to this rule, a drug with good oral bioavailability should have at most 10 rotatable bonds and a topological polar surface area (TPSA) equal to or less than 140 Å2 [13,14]. The application of these rules is crucial for the optimization of new compounds, allowing an initial screening to select molecules with greater probability of success as oral drugs.

This study aimed to perform a comparative analysis of the drug-like properties of cephalosporins belonging to different generations, through molecular descriptors, in order to verify structural and pharmacokinetic patterns that influence their bioavailability and oral administration profile.

2. Results

2.1. Trends in Molecular Descriptors Across Cephalosporin Generations

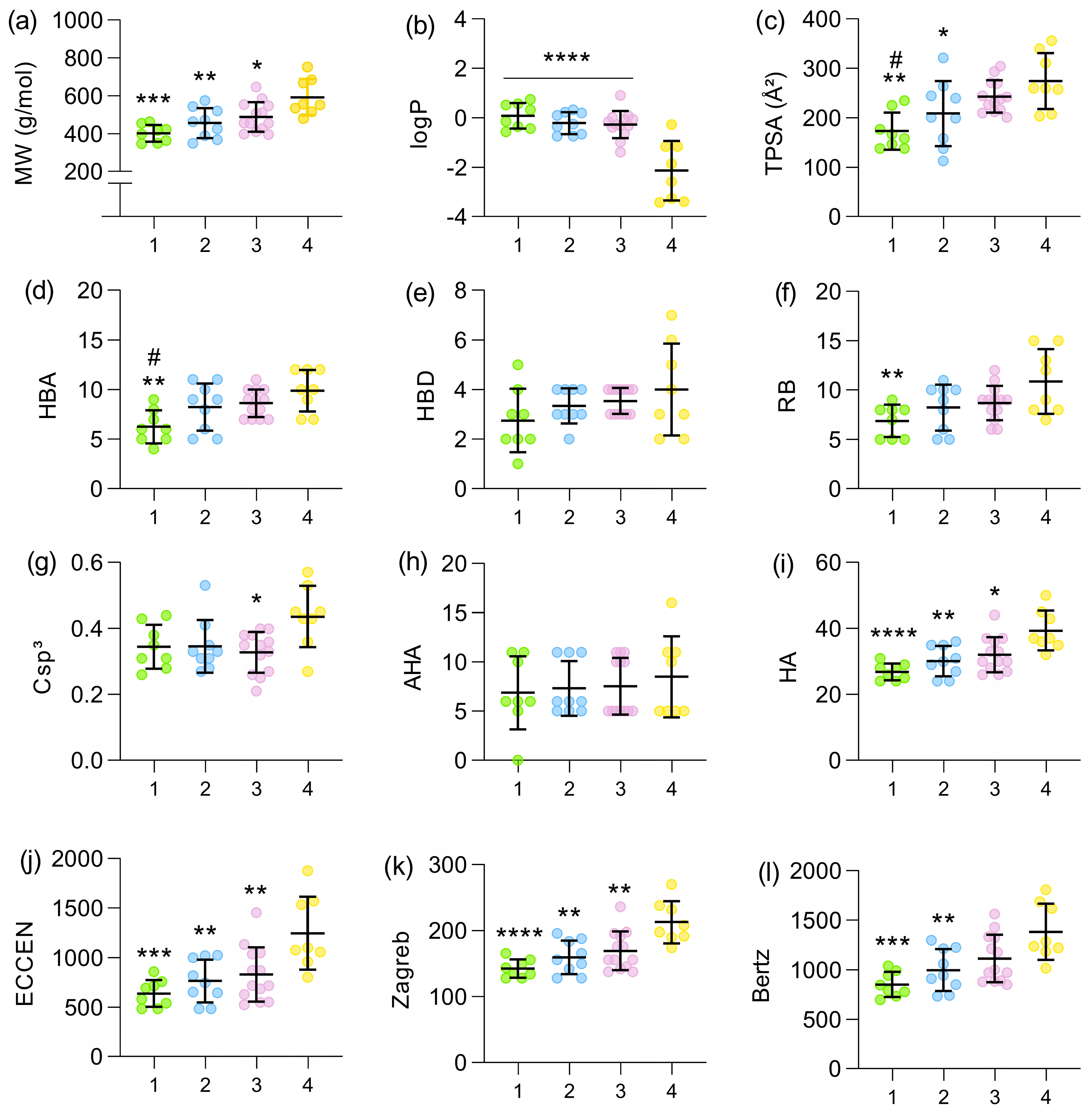

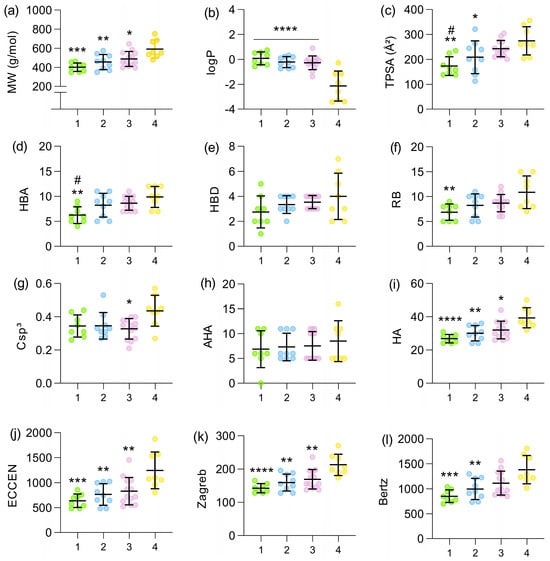

There is a trend toward increasing molecular weight as new generations of cephalosporins have been developed (Figure 1a). A significant difference was found between the molecular weight of the first and fourth generations, with p = 0.0001 (for statistical purposes, fourth- and fifth-generation cephalosporins were analyzed as a single group). When comparing the second and third generations with the fourth, significant differences were also found, although less pronounced (p = 0.0047 and p = 0.0236, respectively). Fourth-generation cephalosporins became much more polar when compared with the first (p < 0.0001), second (p < 0.0001), and third generations (p < 0.0001). This drastic decrease in logP values can be observed in Figure 1b. Regarding TPSA, a significant increase was found in the fourth generation when compared with the first (p = 0.0011) and second (p = 0.0416) generations. A difference was also identified between the TPSA values of the first and third generations (p = 0.0144), as shown in Figure 1c. Considering the number of hydrogen bond acceptors (Figure 1d), an increasing trend can be observed across generations, with significant differences identified between the first and fourth generations (p = 0.0025) and the first and third generations (p = 0.0385). The number of hydrogen bond donors was the parameter least affected, with no significant differences identified, as shown in Figure 1e. Cephalosporins became more flexible as new generations were developed, as shown in Figure 1f. The greatest differences in this parameter occurred between the first and fourth generations (p = 0.0063). Additionally, only a slight, non-significant increase in the fraction of sp3 carbons (Csp3) was observed in more recent generations (Figure 1g). The number of aromatic heavy atoms (AHAs) remained relatively constant across generations, suggesting that the aromaticity of the scaffold was not the main driver of structural optimization (Figure 1h). In contrast, the total number of heavy atoms (HAs) increased progressively from the first to the fourth generation, with significant differences between the extremes, reflecting the growing structural complexity of modern derivatives (Figure 1i). In addition, three global indices of molecular complexity were evaluated: the eccentric connectivity index (ECCEN), which combines information on atom degree and distance in the molecular graph; the Zagreb index, which sums the squared degrees of atoms; and the Bertz index, a composite topological measure that increases with molecular size, branching, and heteroatom content. A similar pattern was observed for these descriptors (Figure 1j–l): all three showed significantly lower values in first-generation cephalosporins and progressively higher values in later generations, with the largest differences occurring between the first and fourth generations, indicating a marked increase in overall topological and connectivity complexity across the series. The complete set of molecular descriptors calculated for each cephalosporin analyzed in this study is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1.

Mean values of molecular weight (a), logP (b), TPSA (c), HBA (d), HBD (e), rotatable bonds (f), Csp3 (g), AHA (h), and HA (i), ECCEN (j), Zagreb index (k), and Bertz complexity index (l) across the four generations of cephalosporins (x-axis). The dataset (n = 38) is distributed as 1st Gen (n = 8; 50% oral, green points), 2nd Gen (n = 9; 33.33% oral, blue points), 3rd Gen (n = 13; 30.77% oral, purple points), and 4th/5th Gen (n = 8; 0% oral, yellow points). The fourth-generation group also included fifth-generation cephalosporins, due to the absence of a clear distinction between these generations and the limited number of cephalosporins classified as fifth generation. * indicates significant difference relative to the 4th generation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001; # indicates significant difference relative to the 3rd generation: # p < 0.05. All comparisons were performed using Tukey’s post hoc test, except for HBD and AHA, which were analyzed using Dunn’s test.

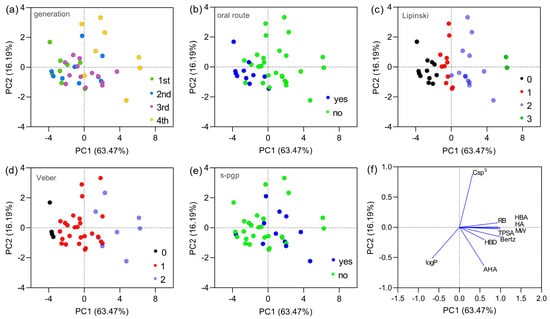

2.2. Principal Component Analysis and Compliance with Drug-Likeness Rules

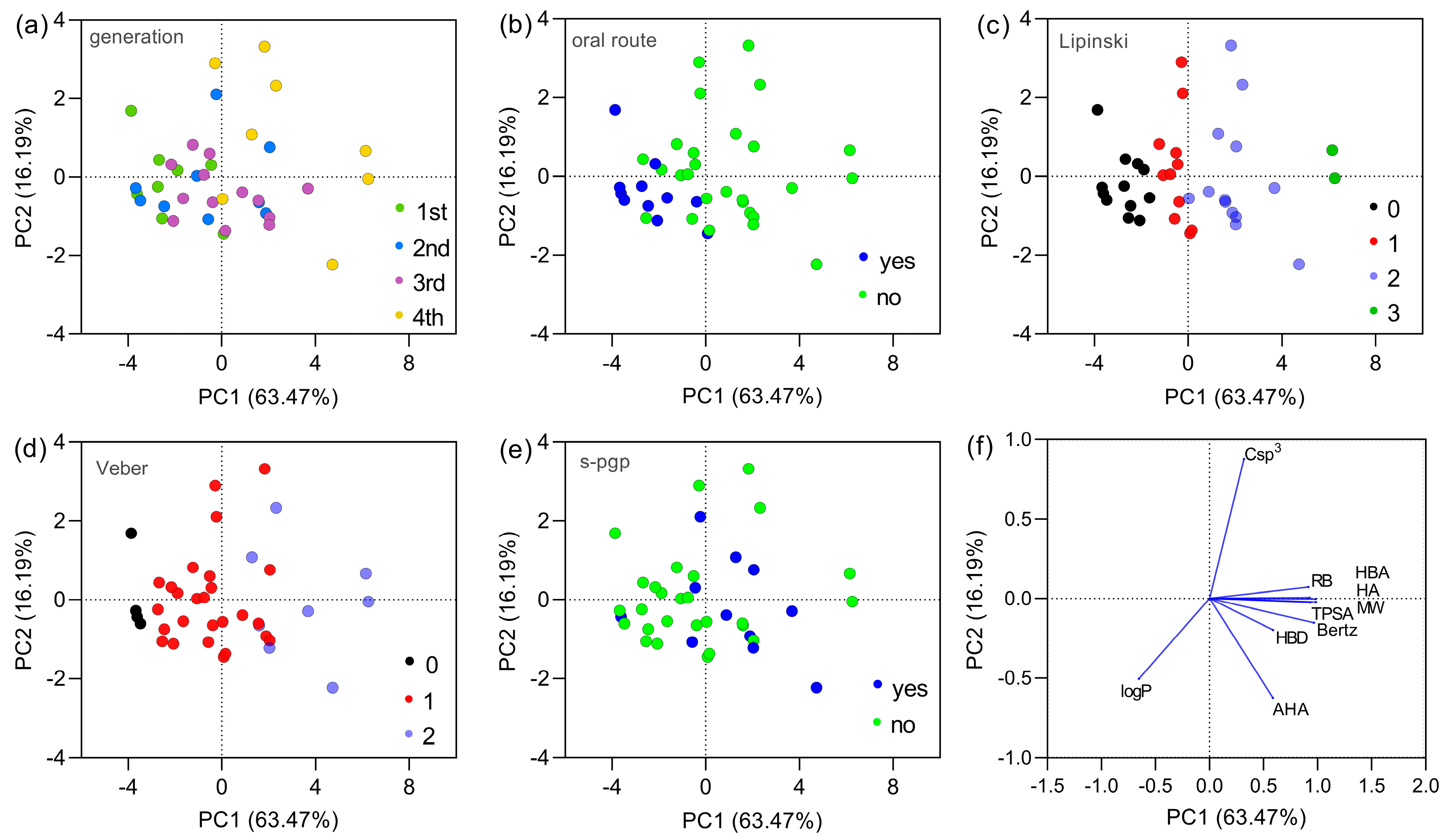

Aiming to reduce data dimensionality and visualize how cephalosporins populate chemical space, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed. A subset of descriptors (MW, logP, TPSA, HBA, HBD, RB, Csp3, AHA, HA, and Bertz complexity) was retained to represent size, polarity, hydrogen-bonding capacity, flexibility, aromaticity, and global molecular complexity. Because the eccentric connectivity and Zagreb indices were colinear with both the Bertz index, only the Bertz index was retained as the global measure of molecular complexity in the PCA, ensuring an adequate ratio between the number of variables and experimental observations. In Figure 2a, it is observed that first-, second-, and third-generation cephalosporins are predominantly distributed in the left quadrants of the graph, while fourth-generation cephalosporins concentrate in the right quadrants. This pattern suggests significant differences in physicochemical properties across generations. In Figure 2b, when considering oral administration routes, drugs with oral formulations (in blue) are concentrated in the left quadrants. On the other hand, fourth- and fifth-generation cephalosporins (in green) do not present oral formulations, which is evidenced by their distinct location. Figure 2c shows that some first- and second- generation cephalosporins exhibit compliance with Lipinski’s Rule, concentrating near the graph’s origin. However, third- and fourth- generation compounds are predominantly distributed in more distant regions, indicating a greater number of violations. Among all compounds, cefiderocol and ceftolozane form the two rightmost points along PC1, occupying the extreme region of the ‘size–polarity–complexity’ axis. Both present three Lipinski’s rule violations and two Veber’s rule violations and are predicted to act as P-glycoprotein substrates, thereby concentrating multiple unfavorable features for oral absorption in a single scaffold. Figure 2d shows that some first- and second-generation cephalosporins present no violations of Veber’s Rule, whereas fourth-generation compounds exhibit, in most cases, at least one violation. In Figure 2e, it is observed that compounds identified as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrates (in blue) are predominantly from the third and fourth generations, suggesting a possible impact on the bioavailability of these drugs. Figure 2f (PCA vector plotting) reveals that the variables with the greatest contribution to PC1 values were the number of rotatable bonds, topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) and acceptors (HBAs), number of heavy atoms, and Bertz complexity. PC2 values were more influenced by the sp3 carbon fraction and aromatic heavy atoms. The logP parameter contributed to both components. The vector plot also highlights important inverse relationships, such as between Csp3 and aromatic heavy atoms, located in opposite quadrants, as well as between Csp3 and logP.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the dataset constructed from molecular descriptors of the 38 cephalosporins analyzed. Panels (a–e) show the distribution of cephalosporins according to PC1 and PC2, which together explain 81.14% of the total variance, grouped by (a) generation (1st generation, n = 8; 2nd generation, n = 9; 3rd generation, n = 13; and 4th/5th generation, n = 8), (b) availability of oral formulations (yes, n = 11; no, n = 27), (c) number of Lipinski’s rule violations (0 violations, n = 11; 1 violation, n = 11; 2 violations, n = 13; 3 violations, n = 3), (d) number of Veber’s rule violations (0 violations, n = 4; 1 violation, n = 26; 2 violations, n = 8), and (e) potential to act as P-glycoprotein substrates (yes, n = 11; no, n = 27). Panel (f) presents the loading (vector) plot, illustrating the contribution of each variable to the observed distribution patterns and the correlations among descriptors. Fourth-generation cephalosporins also include fifth-generation compounds, due to the lack of a clear distinction between these generations and the limited number of agents classified as fifth generation.

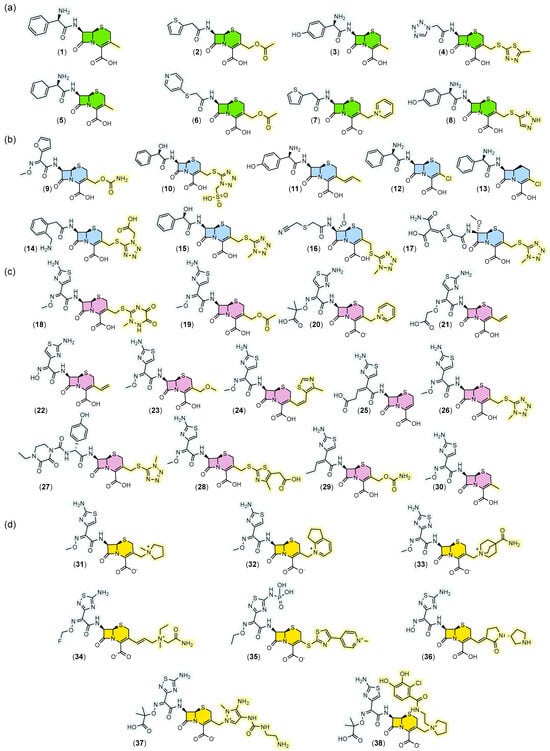

2.3. Structural Substitution Patterns at C3 and C7 Positions

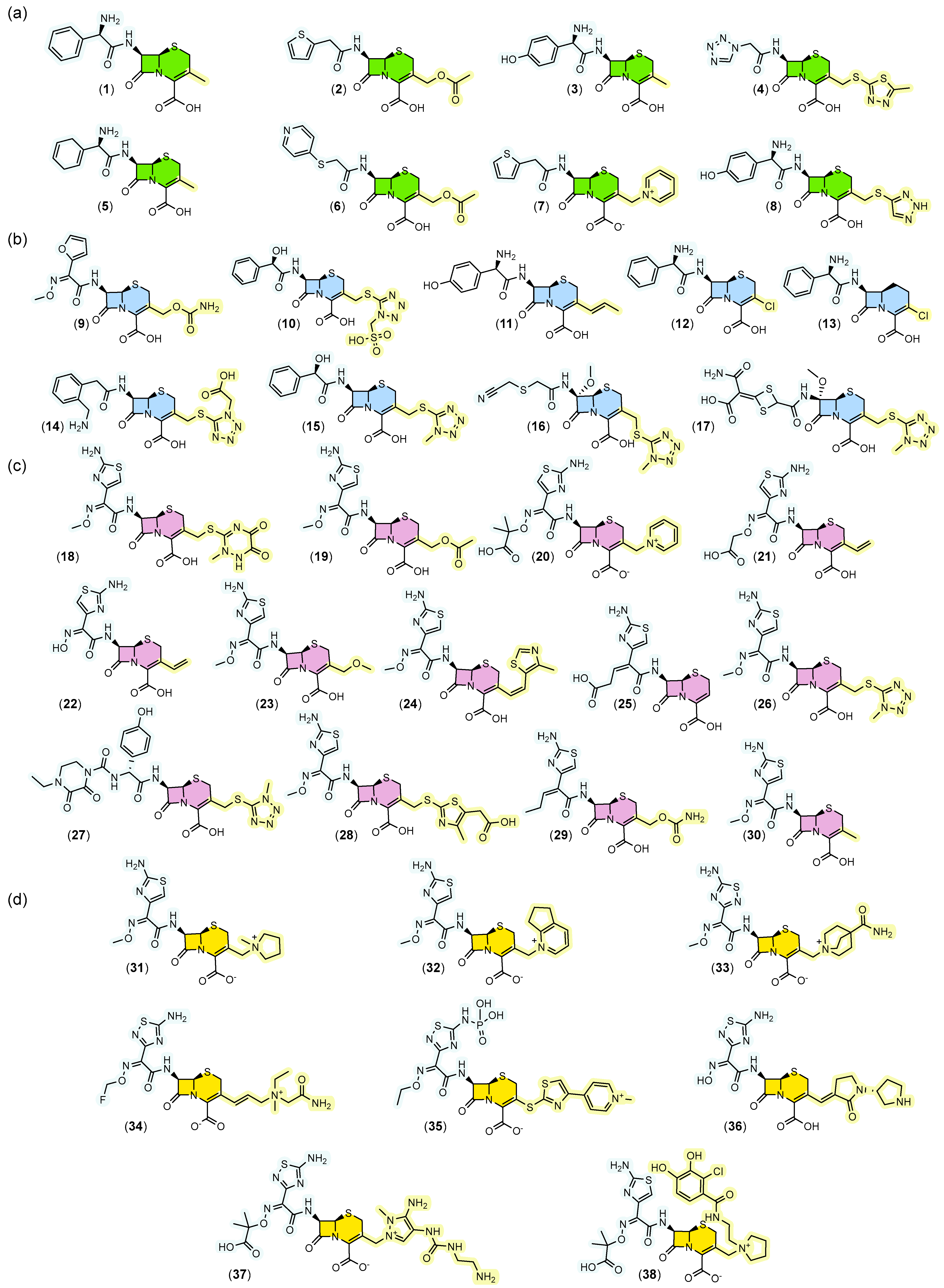

Evaluation of substitution patterns at positions C3 and C7 of the 7-ACA core revealed important structural trends across generations. In the first generation (Figure 3a) a small structure diversity and complexity may be observed at position C3. From the second generation (Figure 3b) onward, recurrent emergence of tetrazole groups (10, 14–17, 26, 27) at position C3 is observed, a characteristic that tends to disappear in later generations. Oximes began to be incorporated predominantly at position C7 from the second generation onward, with increasing prevalence in subsequent generations, especially in the fourth generation, where these functions predominate.

Figure 3.

Structures of cephalosporins grouped by generation. In (a) first generation, (b) second generation, (c) third generation, (d) fourth and fifth generation. In each generation the scaffold is represented in different colors. The substituent group at position 7 is highlighted in blue and the substituent group at position 3 is highlighted in yellow. Cephalexin (1), Cefazolin (2), Cefadroxil (3), Cephalothin (4), Cephradine (5), Cephaloridine (6), Cefapirin (7), Cefatrizine (8), Cefuroxime (9), Cefonicid (10), Cefprozil (11), Cefaclor (12), Loracarbef (13), Ceforanide (14), Cefamandole (15), Cefmetazole (16), Cefotetan (17), Ceftriaxone (18), Cefotaxime (19), Ceftazidime (20), Cefixime (21), Cefdinir (22), Cefpodoxime (23), Cefditoren (24), Ceftibuten (25), Cefmenoxime (26), Cefoperazone (27), Cefodizime (28), Cefcapene (29), Cefetamet (30), Cefepime (31), Cefpirome (32), Cefclidine (33), Cefluprenam (34), Ceftaroline (35), Ceftobiprole (36), Ceftolozane (37), Cefiderocol (38). All colors are used consistently with the previous figures: green for the first generation, blue for the second, purple for the third and yellow for the fourth and fifth.

In the third generation (Figure 3c), the appearance of the aminothiazole group (18–26, 28–32, 38) at position C7 is noteworthy, which was consistently maintained in the fourth generation.

As shown in Figure 3, a conserved pattern was identified at position four of the β-lactam ring, where the carboxyl group (COOH) remained free in all analyzed generations, indicating probable importance for interaction with penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) and maintenance of antibacterial activity.

Furthermore, the fourth generation (Figure 3d) is distinguished by highly functionalized substitutions and increased volume of groups at position C3. The presence of charges (31–35, 37–38) and oximes was also notable in this generation.

In contrast, in the first two generations, there is a significant frequency of benzyl groups (1, 3, 5, 8, 10–15) substituted by amino or alcohol functions at the alpha position, suggesting early strategies to increase solubility and interaction with biological targets.

3. Discussion

The progressive increase in molecular weight and in the total number of heavy atoms across cephalosporin generations indicates the systematic introduction of bulkier and more elaborated side chains onto the β-lactam and dihydrothiazine cores. In earlier generations, side-chain optimization was largely driven by the need to broaden the antibacterial spectrum and to address emerging β-lactamase-mediated resistance, leading to the incorporation of additional heteroatoms and polar functionalities [4,16]. In later generations, this strategy appears to have intensified, resulting in scaffolds that are not only heavier but also markedly more polar and conformationally flexible, as reflected by the higher TPSA values, increased numbers of hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, and a greater number of rotatable bonds observed in our dataset. These trends are consistent with medicinal chemistry efforts described for contemporary antibacterial agents, in which the quest for potent activity against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens often prioritizes target engagement and stability against enzymatic degradation over the maintenance of classical oral drug-likeness profiles [8,16].

Furthermore, the significant decrease in logP in fourth- and fifth-generation cephalosporins indicates an increase in molecular polarity, which can be interpreted as an attempt to avoid passage through lipophilic membranes, even though this change impairs oral bioavailability [17,18]. This finding is consistent with results obtained by Lin and Kück [19], who highlight the role of structural design of cephalosporins as a response to increasing bacterial resistance. The position of cefiderocol and ceftolozane within this map is particularly illustrative: both occupy the extreme high-PC1 region, simultaneously violate Lipinski’s and Veber’s criteria, and are predicted to act as P-gp substrates, concentrating several unfavorable features for oral delivery in a single scaffold. This behavior is consistent with their clinical use as exclusively parenteral agents targeting multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections, and mirrors broader observations that highly polar, multi-charged antibiotics rarely achieve acceptable oral bioavailability [20].

The elevation of TPSA and HBA in more recent generations suggests a greater capacity to form hydrogen bond interactions [14]. Although this may increase affinity for biological targets, this trend toward polarity tends to reduce penetration through cell membranes, particularly via the oral route, as it hinders passive diffusion. The relationship between physicochemical parameters and cell membrane permeation is a critical factor influencing activity and susceptibility to efflux mechanisms [7,10,17,21]. Such alterations explain why more modern cephalosporins are mostly administered parenterally, which increases efficacy at the expense of oral bioavailability throughout the class evolution [4,22].

In our series, the fraction of sp3 carbons showed only a modest increase across generations, indicating that most cephalosporin optimization has relied on adding polar and bulky substituents without substantially increasing saturation. A higher Fsp3 content tends to limit the growth of logP, break molecular planarity, expose polar atoms, and hinder π–π stacking, features that are generally associated with improved aqueous solubility and more favorable physicochemical behavior in drug-like space [23]. In an attempt to explain these observations, Lovering et al. further demonstrated that saturation correlates with solubility and clinical success in several small-molecule series, suggesting that greater three-dimensionality can help reconcile potency with developability. In contrast, modern cephalosporins appear to have achieved their enhanced activity predominantly through increases in size and polarity rather than through systematic ‘escape from flatland’, which may contribute to their limited oral bioavailability [23].

Principal component analysis (PCA) clearly demonstrated the transition between generations: compounds from generations 1 to 3 are concentrated in quadrants associated with better compliance with Lipinski’s and Veber’s criteria [12,15], whereas those from generations 4 and 5 deviate from these criteria, reflecting the prioritization of antimicrobial efficacy over oral absorption [17,24].

C3/C7 substituents have documented associations with plasma protein binding, with tetrazole-containing cephalosporins generally showing increased albumin binding, whereas pyridinium or quaternary ammonium motifs tend to reduce protein binding, although this effect is modulated by the overall molecular context [25].

Cephalosporins are predominantly ionizable molecules and often display zwitterionic character at physiological pH, which influences their bacterial uptake, particularly in Gram-negative species where porin-mediated transport is a key determinant [26]. This characteristic explains some limitations of classical drug-likeness rules for this class of compounds. In this context, the descriptors used in the present study were selected to enable a consistent comparative analysis across all cephalosporin generations, with the primary goal of identifying structural and physicochemical trends rather than optimizing permeability.

These results demonstrate that the development of cephalosporins followed a trajectory in which optimization of molecular interactions with bacterial targets and resistance to β-lactamases were prioritized, which compromised some standard parameters of druggability and oral administration [4,10,19].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

Thirty-eight cephalosporins representative from a total of approximately sixty approved worldwide [27], representing the main marketed agents across five generations, were selected. Molecular data for each compound were obtained from the PubChem platform (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 23 November 2025), from which SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) corresponding to cephalosporin structures were extracted. The SMILES were organized in a database constructed in Microsoft Excel® and subsequently used for reconstruction of molecular structures in ChemDraw® 2023 software. After validation, structures were submitted to the SwissADME [28] and ChemDes platforms [29], which were used to predict molecular descriptors and drug-like properties, such as molecular weight (MW), octanol–water partition coefficient (logP), topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), number of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), number of rotatable bonds (RBs), sp3 carbon fraction (Csp3), number of aromatic heavy atoms (AHAs), total number of heavy atoms (HAs), global complexity indices (ECCEN, Zagreb, and Bertz), and pharmacokinetic parameters (P-glycoprotein substrate). The complete dataset, including all calculated molecular descriptors and compound identifiers, is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

4.2. Data Analysis

Values of collected parameters were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and their normality was investigated. Subsequently, mean values were compared among the generations using one-way ANOVA in its parametric or non-parametric versions, according to data adherence to normal distribution. Post hoc comparisons between cephalosporin generations were carried out using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for normally distributed data, or Dunn’s test as a non-parametric alternative when normality was not met. For comparative analyses, fourth- and fifth-generation cephalosporins were analyzed as a single group due to the limited number of fifth-generation agents, which could compromise statistical robustness. In addition, it is important to note that generational classifications are not fully standardized, and certain agents, such as ceftaroline and ceftobiprole, are often referred to in the literature as advanced-generation cephalosporins rather than being strictly assigned to a fifth-generation category. p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Principal component analysis was performed to synthesize the dataset and analyze patterns. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9® software.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that with the advancement of cephalosporin generations, there was a pattern of increased polarity, molecular weight, and molecular flexibility of compounds, with direct consequences on their pharmacokinetic properties. Although these alterations focused on combating bacterial resistance and expanding the spectrum of action, they also resulted in a greater number of violations of Lipinski’s and Veber’s rules, compromising the oral use of more modern generations.

Understanding these structural changes not only clarifies the evolutionary trajectory of cephalosporins but also guides future rational development strategies, aiming to achieve the ideal balance between antimicrobial potency and pharmacokinetic profile, indispensable for therapeutic efficacy. These findings not only explain the evolutionary past of cephalosporins but also point to promising directions for the design of next-generation antibiotics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ddc5010012/s1, Dataset S1: Spreadsheet containing the raw and processed data used for all analyses presented in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L.G.; methodology, I.L.G. and H.d.A.M.; software, H.d.A.M.; validation, I.L.G. and H.d.A.M.; formal analysis, H.d.A.M.; investigation, H.d.A.M.; resources, I.L.G.; data curation, H.d.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.d.A.M.; writing—review and editing, I.L.G.; visualization, H.d.A.M.; supervision, I.L.G.; project administration, I.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge CNPq and FAPERGS for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 7-ACA | 7-aminocephalosporanic acid |

| AHA | Aromatic heavy atoms |

| Gen | Generation |

| HBA | Hydrogen bond acceptors |

| HBD | Hydrogen bond donors |

| LogP | Octanol–water partition coefficient |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| PBPs | Penicillin-binding proteins |

| PC | Principal component |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| RB | Rotatable bonds |

| SMILES | Simplified molecular input line entry system |

| TPSA | Topological polar surface area |

References

- Dave, D.; Mittal, I. A Comprehensive Review of Cephalosporin Antibiotics: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Considerations, Extended Infusion Strategies, and Clinical Outcomes. PEXACY Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, G.L. An Introduction to Medicinal Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, E.P. Cephalosporins 1945–1986. Drugs 1987, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, R.; Cornaglia, G.; Ligozzi, M.; Mazzariol, A. The Final Goal: Penicillin-Binding Proteins and the Target of Cephalosporins. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000, 6, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F.; Terrak, M.; Ayala, J.A.; Charlier, P. The Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Structure and Role in Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.M.; da Silva, B.N.M.; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-Lactam Antibiotics: An Overview from a Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radouane, A.; Péhourcq, F.; Tramu, G.; Creppy, E.E.; Bannwarth, B. Influence of Lipophilicity on the Diffusion of Cephalosporins into the Cerebrospinal Fluid. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 10, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, S.T.; Fredlund, H.; Nicolas, P.; Caugant, D.A.; Olcén, P.; Unemo, M. Antibiotic Susceptibility and Characteristics of Neisseria Meningitidis Isolates from the African Meningitis Belt, 2000 to 2006: Phenotypic and Genotypic Perspectives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.M.; Connolly, K.L.; Aberman, K.E.; Fonseca, J.C.; Singh, A.; Jerse, A.E.; Nicholas, R.A.; Davies, C. Molecular Features of Cephalosporins Important for Activity against Antimicrobial-Resistant Neisseria Gonorrhoeae. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the Chemical Beauty of Drugs. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25, Reprint in Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohit, N.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, H.; Yadav, J.P.; Singh, K.; Kumar, P. Description and In Silico ADME Studies of US-FDA Approved Drugs or Drugs under Clinical Trial Which Violate the Lipinski’s Rule of 5. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 1334–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Rodrigues, G.; Avelino, J.A.; Siqueira, A.L.N.; Ramos, L.F.P.; dos Santos, G.B. The Use of Free Softwares in Practical Class about the Molecular Filters of Oral Bioavailability of Drugs. Quim. Nova 2021, 44, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoorza, A.M.; Duerfeldt, A.S. Guiding the Way: Traditional Medicinal Chemistry Inspiration for Rational Gram-Negative Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhlapho, S.; Nyathi, M.; Ngwenya, B.; Dube, T.; Telukdarie, A.; Munien, I.; Vermeulen, A.; Chude-Okonkwo, U. Druggability of Pharmaceutical Compounds Using Lipinski Rules with Machine Learning. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 3, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeef, A. Absorption and Drug Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Kück, U. Cephalosporins as Key Lead Generation Beta-Lactam Antibiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 8007–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, D.; Takakusa, H.; Nakai, D. Oral Absorption of Middle-to-Large Molecules and Its Improvement, with a Focus on New Modality Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zahed, S.S.; French, S.; Farha, M.A.; Kumar, G.; Brown, E.D. Physicochemical and Structural Parameters Contributing to the Antibacterial Activity and Efflux Susceptibility of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e01925-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Díaz, J.R.; Neveros-Juárez, F.; Arellano-Mendoza, M.G.; Quintana-Zavala, D.; Lara-Salazar, O.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G.; Guevara-Salazar, J.A. QSAR Analysis of Five Generations of Cephalosporins to Establish the Structural Basis of Activity against Methicillin-Resistant and Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Divers. 2024, 28, 3027–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, F.; Bikker, J.; Humblet, C. Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, M.; Komsta, L.; Opoka, W.; Starek, M. Chemometric Analysis of Chromatographic Data in Stability Investigation of Cephalosporins. Acta Chromatogr. 2018, 30, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, E.; Parks, J.; Austin, D.L. Structural Analysis and Protein Binding of Cephalosporins. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcour, A.H. Outer Membrane Permeability and Antibiotic Resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger, C.M.; Franklin, M.; Oler, E.; Wilson, A.; Pon, A.; Cox, J.; Chin, N.E.; Strawbridge, S.A.; et al. DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Cao, D.-S.; Miao, H.-Y.; Liu, S.; Deng, B.-C.; Yun, Y.-H.; Wang, N.-N.; Lu, A.-P.; Zeng, W.-B.; Chen, A.F. ChemDes: An Integrated Web-Based Platform for Molecular Descriptor and Fingerprint Computation. J. Cheminform. 2015, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.