Abstract

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics increasingly inform sustainable investment yet suffer from inter-rater heterogeneity and incomplete reporting, limiting their utility for forward-looking allocation. In this study, we developed and validated a two-level stacked-ensemble machine-learning framework to predict total ESG risk scores for S&P 500 firms using a comprehensive feature set comprising pillar sub-scores, controversy measures, firm financials, categorical descriptors and geospatial environmental indicators. Data pre-processing combined median/mean imputation, one-hot encoding, normalization and rigorous feature engineering; models were trained with an 80:20 train–test split and hyperparameters tuned by k-fold cross-validation. The stacked ensemble substantially outperformed single-model baselines (RMSE = 1.006, MAE = 0.664, MAPE = 3.13%, = 0.979, CV_RMSE_Mean = 1.383, CV_R2_Mean = 0.957), with LightGBM and gradient boosting as competitive comparators. Permutation importance and correlation analysis identified environmental and social components as primary drivers (environmental importance = 0.41; social = 0.32), with potential multicollinearity between component and aggregate scores. This study concludes that ensemble-based predictive analytics can produce reliable, actionable ESG estimates to enhance screening and prioritization in sustainable investment, while recommending human review for extreme predictions and further work to harmonize cross-provider score divergence.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics are increasingly understood as decisive determinants of a corporation’s durability and societal stewardship. Consequently, asset managers and institutional investors rely on investor-grade ESG scores to delineate firms likely to generate sustained economic value from those encumbered by latent ecological or societal hazards. Empirical research reveals a robust empirical link between elevated ESG performance and a moderating effect on borrowing costs, suggesting that credit providers internally ascribe a lower risk premium to firms exhibiting superior scores. Projections corroborate a ballast shift toward ESG-oriented portfolios: Bloomberg Intelligence anticipates that global capital allocated to environmentally aligned investments will surpass USD 53 trillion by 2025, whilst the proportion of constituents in the S&P 500 with formally disclosed ESG ratings surged from 20 to 90 percent between 2011 and 2019. Such expansionary tendencies constitute compelling empirical underpinnings in favour of applying advanced, data-receptive methodologies in the predictive modeling of ESG performance, as legacy grading exercises become inextricably intertwined with forward-looking capital-allocation choices [1,2].

1.2. Role of ESG in Sustainable Finance

ESG ratings serve as central instruments for orienting sustainable finance and investment paradigms. By evaluating environmental stewardship, social impact and governance integrity, ESG scores facilitate the incorporation of non-financial dimensions into investment and asset-allocation frameworks [2]. As such, they function simultaneously as leading indicators of prospective financial risk—subpar ESG performance often presages material losses—and as obligatory filters for responsible investing, where clients opt to divest from or avoid firms with low ESG scores for ethical or reputational motives [3]. Quantitative assessments substantiate the linkage between ESG performance and capital-market outcomes; for example, Apergis et al. (2022) [1] demonstrate that issuers with robust ESG ratings incur narrower bond spreads, even when accounting for conventional risk covariates. However, the relationship is not monolithic; Bifulco et al. (2023) [4] report an anomalous, inverse correlation between ESG scores and equity-market valuation, underscoring the heterogeneous and contingent interpretations that investors ascribe to designated ESG factors. In aggregate, the prevailing view is that the financial community consolidates around the view that ESG data constitute inalienable inputs in valuation models; Sciarelli et al. (2021) [5] contend that systematic incorporation and transparent disclosure of ESG benchmarks will be decisive in redirecting capital flows toward sustainable innovation and inclusive growth.

1.3. Research Problems and Objectives

Sustainable finance increasingly employs ESG metrics as foundational instruments; thus, enhancing ESG analysis via predictive modeling becomes essential for guiding investment decisions rooted in sustainability principles.

A confluence of analytical lacunae constrains the presently available ESG intelligence. Foremost among these is heterogeneity across scores, which arises from divergent methodological, temporal and sourcing choices in the industry. Diverse rating firms, applying proprietary and inconsistent frameworks, generate competing evaluations of the same issuer. Clément et al. (2022) [2] observe a sustained academic debate over the construct validity of ESG scores, a disagreement leading to variable operational definitions across empirical studies. No less significant is the overall qualitative solidity of measurement, which is invariably limited. Clément et al. (2022) [2] contend that extant scores predominantly encapsulate corporate survival prospects rather than forward-looking sustainability optimisation; concomitantly, Senadheera et al. (2021) [6] identify systematic aggregation and model misrepresentation in the environmental domain as attenuating predictive reliability. Such limitations compel both market participants and the firms themselves to treat raw ESG scores as preliminary rather than conclusive indicators in investment processes. ESG ratings are becoming more and more important in both academic and business contexts [7].

The present research addresses the leveraging of machine learning (ML) methodologies to forecast and potentially enhance corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings in a systematic, data-centric manner. This study, therefore, is framed around the following objectives:

- Development and independent verification of ML architectures capable of deriving ESG ratings from a comprehensive suite of corporate and financial data.

- Synthesis of heterogeneous and, to some extent, real-time data reservoirs, including, for the first time, innovative environmental indices, in order to elevate the granularity and robustness of the prediction.

- Enablement of sustainable investment decision-making through the generation of more transparent, harmonized and data-driven ESG evaluations.

Success in meeting these foregoing objectives seeks to mitigate the prevailing liabilities of heterogeneity and missing data in existing ESG metrics and thereby furnish investors with a more solid foundation for sustainable capital allocation.

1.4. Contributions of This Study

This work provides multiple contributions at the interface of ESG assessment and machine learning. First, it advances a holistic conceptual schema for the ML-based estimation of ESG ratings, encompassing a wide variety of explanatory variables—financial performance, social behaviour, governance structure and environmental footprint—while benchmarking a diverse array of learning algorithms. Second, it remedies acknowledged methodological voids: in particular, following the approach of Senadheera and colleagues (2021) [6], this study decomposes the environmental component through fine-grained indicators in order to contain the often-observed aggregation bias.

Third, the present study constitutes one of the initial efforts to employ predictive analytics in the context of ESG scoring, moving beyond the conventional retrospective examination of ESG outcomes, thereby enacting the prescription articulated by Clément et al. (2023) [7] to reconceptualize ESG metrics as quantitative phenomena subject to formal, rigorous modeling. This paper further provides empirical evidence that machine learning-driven estimates of future ESG characteristics furnish investors with a robust, evidence-based foundation for making sustainable investment choices. Collectively, our contributions reside in the interface between ESG scholarship—characteristically dominated by theoretical exposition and correlation analysis—and established artificial intelligence methodologies, yielding forward-looking, operationally relevant ESG forecasts that can inform practitioner action.

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Scoring and Sustainable Finance

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings distill multiple sustainability dimensions into a single quantitative metric, positing that the durability of superior corporate conduct is positively correlated with future financial advantage and downside risk moderation. Analysts and asset managers frequently treat ESG ratings as surrogates for enterprise resilience under the assumption that firms receiving high ratings possess reflexive capacities capable of absorbing legislation, resource scarcity and socio-political scrutiny. Hence, ESG ratings functionally segregate convictions—endowing “sustainable and responsible” firms with liquidity advantages and relegating their “non-compliant” peers to deeper due-diligence hurdles. Market practitioners already anticipate a future in which ESG-dedicated portfolios govern a third of global asset volumes, a trajectory Bloomberg expects to be realized imminently.

Empirical evidence corroborates the finance-professional expectation that ESG rating increments grant material fiscal concessions. Apergis et al. [1] present a liquidity-collected dataset demonstrating a robust, cross-sectionally stable inverse relationship between ESG scoring and debt market spreads, asserting that debt holders apply a risk–price discount to securities of firms demonstrating ESG negligence, even when judiciously controlling for the canonical financial covenants. Concomitantly, Bifulco et al. [4] identify an anomalous, non-linear elasticity between composite ESG indicators and short-horizon market-adjusted value, intimating that the value realignment embedded in rapidly evolving market predispositions generates currency pressure that challenges a one-dimensional, linear portrayal of ESG orientation and fundamental equity revaluations.

Such divergent findings reinforce the notion that although ESG factors exert material weight on investment analysis, their financial consequences remain substantially context-specific.

Recognizing their utility, the ongoing analysis reveals that ESG scores are nevertheless bounded by significant limitations. Clément et al. [2] observe that extant empirical work demonstrates that ratings do not encompass the full spectrum of a firm’s sustainability performance. Instead, metrics predominantly gauge the extent to which environmental and social issues pose a threat to profitability. Consequently, a firm may attain a favourable score by mitigating exposure—for example, by publicizing an emission reduction target—while the substantive environmental contribution remains modest. Environmental sub-indices confront especially acute comparability constraints: Senadheera et al. [6] contend that measurement bias and the absence of a uniform methodological standard across providers render E scores frequently inconsistent and “of limited usefulness” in inducing structural greening of the financial system. Further inconsistency is reported by Dumrose et al. and Li et al. [8,9], who demonstrate that disparate providers produce scores that follow divergent trajectories, thereby injecting significant uncertainty into the investment adjudication process. In summary, while ESG metrics now occupy a central place in the architecture of sustainable finance, the scholarly community urges continued circumspection: the scores are, by their nature, partial, context-reliant and heterogeneous instruments, liable to generate discordant signals across prior and prevailing data.

2.2. Applications of Machine Learning in ESG Prediction

Over the past decade, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have gained prominence in environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysis. Emerging scholarly work indicates a broad spectrum of ML algorithms capable of modeling ESG performance and processing the multifaceted datasets inherent to sustainability. Supervised learning, in particular, is the predominant paradigm, facilitating the forecasting of firm-level ESG scores by integrating both quantitative and qualitative features. A recent comprehensive survey of the field documents the utilization of methodological variants, from basic linear regressors to intricate deep networks, in the estimation of ESG ratings [10]. Empirical implementations, cited across multiple studies, demonstrate the training of regression and decision-tree architectures on longitudinal ESG data, leveraging covariates such as industry codes, key financial ratios and structured sustainability narratives. Many authors have evaluated performance using quantified metrics like the root mean square error or R-squared. Furthermore, this comparative analysis reveals that ensemble techniques—especially gradient boosting—often yield superior predictive accuracy relative to baseline linear and non-linear counterparts, underscoring the merits of capturing interaction and non-linearity effects within the datasets.

Beyond the improvement in predictive accuracy, machine learning (ML) enhances interpretability and delivers actionable insight. Algorithms employing Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) have successfully isolated the features most determinative of environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores, such as market capitalization, price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios and classification within sector groupings. Analysis often affirms that the environmental dimension of the scores is principally responsive to metrics of resource consumption and emission intensity. Complementarily, ML accommodates the assimilation of emergent information repositories within the ESG evaluative framework. A recent illustration is presented by Rossi et al. (2024) [11], who synthesize satellite-based geospatial variables—such as land-use classification and ambient emission estimates—within ESG modeling, thereby advancing methodological consistency. Across the surveyed scholarship, it emerges that ML cultivates analytic agility conducive to ESG score generation: the methodology accommodates high-dimensional covariates, reveals latent non-linear relationships and purports to reconcile heterogeneous data originators [12]. Nevertheless, the prevailing corpus is predominantly proof-of-concept in nature, exhibiting limited integration across the ESG triad and failing to confront the persistent challenge of data discord on an explicit basis. The present article extends the corpus through the construction of an artificially intelligent, end-to-end predictive framework aimed squarely at sustainable capital allocation.

2.3. Gaps in Existing Research

The surveyed literature, however, remains uneven. Chief among its limitations is the absence of an explicit, widely accepted conceptualization of the construct underlying ESG score formulation. A previous study highlighted the polymorphic utility ascribed to ESG scores across extant scholarship: certain analyses regard them as markers of corporate sustainability, whilst others deploy them as surrogates for risk-adjusted performance [7]. Such interpretative fluidity counsels restraint, signalling that subsidiary models ought to articulate target constructs with precision. A second concern is the methodological constraint induced by aggregation. Many investigations employ composite ESG ratings, neglecting the heterogeneous dynamics that might govern each foundational pillar [6]. The environmental dimension, for instance, could profit from its own architectural stratification—biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas intensity and ecological footprints may each merit distinct analytic treatment, as opposed to consolidation into a single scalar summary. The third limitation pertains to divergence and bias manifested at the data generation stage. Dumrose et al. (2022) [8] reveal that ESG scores, even when produced under European Union Taxonomy conformance, may exhibit gross divergence across raters. Relevantly, Li et al. (2024) [9] document that differential policy thrust—environmental regimes styled as punitive versus those framed as incentive—further muddies the comparability of ratings. Such divergence implies that models calibrated to a specific vendor’s ESG dataset risk excessive extrapolation error when applied to alternatives. At the conclusive level, a systemic deficiency persists: the scarcity of transparent, integrative methodological frameworks that concurrently accommodate the multidimensional and context-sensitive characteristics of ESG data.

While some works suggest the joint application of ESG parameters and digital transformation initiatives, few predictive models systematically include the interactions among these domains [13]. A systematic review therefore indicates the absence of machine learning solutions that preserve the ESG construct’s multidimensionality (a), compensate for heterogeneity in external and internal data (b) and satisfy long-term sustainability goals during model training (c). Such inadequacies justify this investigation’s concentrated development of an integrative machine learning apparatus tailored for ESG forecasting.

2.4. Research Positioning

Our research is positioned to at the intersection of sustainable finance and artificial intelligence analytics, systematically epidemiologicalizing and redressing the described limitations. The design of a machine learning architecture capable of projecting future ESG evaluations systematically materializes injunction to circumspect application of sustainability indicators and responds to directives to fortify the environmental dimension with sub-component metrics [6,7]. We operationalize this imperative by systematically integrating findings that leverage openly accessible geospatial datasets in order to alleviate inter-rating variance [11]. Concurrently, the design phase of the model foregrounds investment decision architectures, following assertions regarding the necessity of embedding ESG assessments within formal allocation processes [5].

Leveraging the work of Xiao et al. (2023) [3] permits explicit alignment of our predictive model with prevailing sustainable finance innovations—including the expanding domains of impact investing and evolving regional regulatory architectures. Such alignment endows the model’s outputs with operational applicability in contemporary financial markets. Thus, the contribution of the present study is the systematic extension of the existing literature on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors and machine learning (ML) techniques through the introduction of a predictive architecture that is simultaneously exhaustive in its explanatory scope and attentive to sustainability imperatives, thereby advancing the methodological toolkit available to sustainable investment practitioners.

3. Research Framework

3.1. Conceptual Model

Proposed within this research is a conceptual model that recasts the forecasting of ESG scores as a supervised machine learning problem. Each corporation, or alternatively each asset, is represented by a comprehensive set of covariates sourced across the three constituent pillars of ESG. The environmental dimension is operationalized by a battery of observable indicators, which may comprise absolute measurements of greenhouse gas emissions or absolute or intensity-based consumption of key resources, along with infrastructure-dependent, remotely sensed covariates, as evidenced by Rossi et al. (2024) [11]. The social dimension is articulated through discrete panels of metrics, such as the gender or ethnic composition of the workforce, monetized or quantitative proxies of local community investment and indicators of labour standards and policies. The governance dimension is encapsulated by discrete, observable proxies that review the independence, gender and tenure metrics of the board; publicly listed corporate governance policies; and indicia of historical regulatory or self-regulatory breach. To control for residual risk and informational economies, the model may integrate ordinal or continuous metrics of financial size, operating or explanatory returns and delineated sector classification, as already discussed by Apergis et al. (2022) [1].

Following model design, these heterogeneous covariates, drawn from environmental, social, governance and ancillary financial domains, are assembled into multi-source, heterogeneous learning vectors for each firm, pre-processed and concatenated.

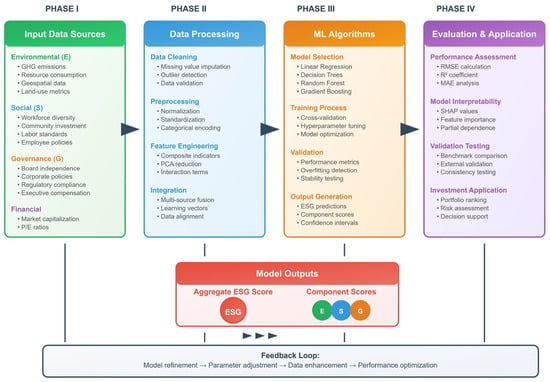

The synthetic vectors are presented in parallel to one or an ensemble of machine learning algorithms, which inductively fit the ensemble against the ESG or ESG sub-component scores, outlined in the enclosed box in Figure 1. Consequently, the architecture delivers one or three continuous or ordinal outputs representing an aggregate ESG assessment or its constituent environmental, social and governance assessments. It is postulated that the environmental variables within the feature set will be hierarchically stored in latent sub-group segments (e.g., community, regional and global metrics).

Figure 1.

ML-based ESG prediction framework.

To capture different effects, the geospatial framework of Rossi et al. (2024) [11] is followed. The learning process of the framework proceeds by calibrating against historical data, utilizing authentic ESG ratings derived from established agencies to iteratively tune the model’s hyperparameters. The overarching structure of the framework thus capitalizes on the extensive and diverse data fabric surrounding ESG determinants, whilst employing cutting-edge machine learning techniques, to yield scores that are empirically justified and compatible with the sustainable finance orientation articulated previously.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

Drawing from the cognitive architecture of the framework, the following empirical conjectures are hereby advanced for systematic validation:

H1.

Predictive machine learning algorithms are expected to account for a statistically significant share of the variability observed in corporate ESG scores.

H2.

Analyses of variable importance are anticipated to disclose a limited subset of predictors—specifically, sectoral affiliation, governance structures and targeted environmental indicators—that exert a robust and recurrent influence on the ESG outcome, in accordance with scholarship established in preceding research.

H3.

Ensemble-based algorithms are expected to achieve superior predictive accuracy compared to linear and kernel-based models.

Even though this study examines the breakdown of environmental, social and governance components, these are considered to be behavioral manifestations of the model rather than being treated as a prior hypothesis.

3.3. Workflow Overview

Data Collection: Our initial dataset comprises a cohort of firms for which two key elements are secured: (1) authoritative ESG ratings sourced from a leading provider and (2) a parallel set of candidate explanatory variables aggregated from issuer filings and curated external registries. The predictors encompass balance sheet disclosures, real-time market observables and specialized ESG indicators, such as GHG emission quantifications and disclosures relating to corporate social policy frameworks. Supplementary geospatial data, including satellite-derived land cover mosaics and atmospheric contamination indices where they exist, are layered to augment the environmental component of the scores.

Data Pre-processing: We move to rigorous data sanitization and alignment routines. Incomplete observations are addressed through state-of-the-art imputation techniques, continuous variables are normalized to a common scale and categorical descriptors (sector of activity, geographical domicile, etc.) are suitable encoded. We pre-empt conflicts of units among disparate datasets and, where a parent aggregated ESG target is provided, decompose them mechanically into their environmental, social and governance components. This step is taken to serve either the parallel fitting of distinct predictive modules or the fitting of a multi-output architecture, as either pipeline evidences superior interpretability.

Feature Engineering: We expand our dataset through the contriving of auxiliary predictors that distill the ESG narrative into analytically tractable variables. Composite indicators, such as capital–emissions ratios or single aggregated community impact scores, are derived and principal component reductions are calculated to expose latent ESG-related signals. Each sub-module, namely environmental, social and governance, is explicitly calibrated to the criteria identified in Clément et al. (2023) [7], who advocate for metrics that are both robust and context-sensitive in definition.

Model Training: The dataset is partitioned into distinct training and hold-out test sets. Within the training set, a variety of supervised learning algorithms are assessed, including linear regression, decision trees, random forests and a range of boosting techniques. Hyperparameters are systematically optimized using k-fold cross-validation, with exhaustive grids and, where relevant, random search applied. Consistent with the literature underscoring their effectiveness, ensemble methods—predominantly gradient boosting—are employed and may be augmented by early-stopping criteria. Should the dimensional and tabular nature of the dataset warrant it, we shall investigate the deployment of multi-layer feed-forward neural networks, contingent on adequate sample size provisions.

Model Evaluation: The efficacy of each fitted model is evaluated against the hold-out test partition, with predictive accuracy quantified by the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), coefficient of determination (R2) and explained variance, and cross-validated by CV_RMSE_Mean, CV_R2_Mean, CV_R2_STD and CV_RMSE_STD. All predictive artefacts are benchmarked against a naive model that forecasts the overall mean ESG score, thereby offering a substantive improvement benchmark. To satisfy H2, global feature importance is derived using feature importance, assessed via permutation-based importance and Pearson correlations (chosen for computational efficiency); future work may extend to SHAP for local explanations.

Implementation and Application: Last, the framework is executed on unseen, out-of-sample firms to produce forward-looking ESG score estimates. These score trajectories are actionable for sustainable investment; for instance, a portfolio manager can rank firms according to its ML-produced ESG estimates, thereby enhancing the granularity offered by legacy scoring systems. The interface of the model to current regulatory and ESG architecture is also examined, building on the notion of tessellating ESG analysis with sectoral digital transformation programs, especially within healthcare [13].

4. Materials and Methods

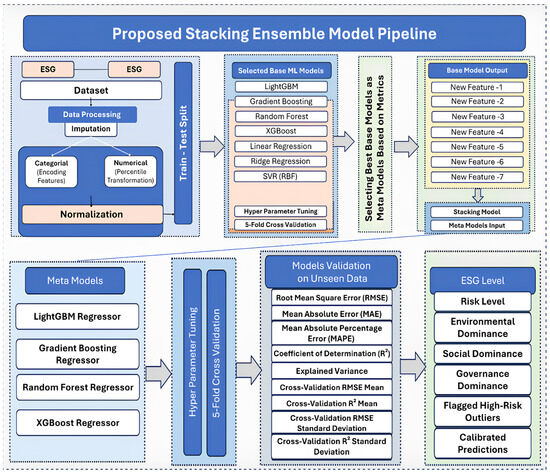

The methodological framework adopted in this study consists of systematic data preparation, pre-processing, feature transformation and model development procedures for ESG risk prediction. Each stage is designed to ensure reproducibility, minimize data bias and optimize predictive performance. Figure 2 demonstrates the methodological framework for the proposed stacking ensemble model pipeline used in this study.

Figure 2.

Proposed stacked-ensemble machine-learning framework to predict total ESG risk scores.

4.1. Dataset Collection

The dataset used in this study is the S&P 500 ESG Risk Ratings dataset [14]. It contains the firm-level environmental, social and governance (ESG) indicators for 503 companies. The dataset comprises environmental, social, governance and controversy indicators obtained from publicly available ESG repositories and commercial databases. The dependent variable is the total ESG risk score, and the independent variables include environmental, social and governance risk scores, together with categorical variables representing risk levels as low, negligible or severe.

The dataset consists of 503 companies × 15 variables. Some firms had missing values in one or more ESG dimensions (e.g., “Total ESG Risk Score” or “component-level scores“). These missing values were addressed during the pre-processing stage using imputation techniques. The dependent variable (response) for this study is the total ESG risk score, while the predictors include the ESG sub-scores, controversy measures and categorical ESG risk levels.

Another dataset, “Environment, Social Furthermore, Governance Data” [15], was used in this study, where the World Bank’s ESG Data Draft collection covers 17 essential sustainability themes, including environmental, social and governance categories. To better align financial flows with global goals, the World Bank Group (WBG) is trying to offer financial markets with improved data and analytics on nations’ sustainability performance. Along with new information and tools, the World Bank will conduct research on the relationship between a country’s sustainability performance and the risk and return profiles of potential investments.

4.2. Data Pre-Processing and Feature Engineering

To ensure high-quality inputs for the regression models, a systematic pre-processing pipeline was applied, covering missing value treatment, feature transformations, encoding, normalization and train–test partitioning. No transformations, such as missing value imputation, categorical encoding, feature scaling or feature engineering, were fitted to any test data. Instead, to minimize data leakage, all transformations were fitted to the training data, (Train). For (k)-folds cross-validation, the pre-processing parameters were scoped and executed independently to each training fold and later applied to the validation fold. Once training for the complete dataset was finished, all transformations for the test set were applied.

4.2.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory analysis was conducted to obtain insight into the structure, distribution and relationships within the dataset before proceeding to model development. The following summary statistics include the mean, median and standard deviation, which were calculated for all numerical features to identify central tendencies and dispersion.

To analyze patterns for missing data, percentage of missing values for each column was computed to inform the imputation strategy. Negligible missing columns (less than 5%) were imputed, and columns that exceeded acceptable levels were examined for exclusion.

A histogram was used to analyze the target variable’s (total ESG risk score) distribution (Figure 6). The selection of scaling and median imputation techniques was influenced by the observed skewness.

To determine the correlations between numerical variables, Pearson correlation matrices were plotted (Figure 6). During regression analysis, highly correlated features were closely watched to minimize any possible multicollinearity problems.

Histograms with KDE and scatter plots were used to detect extreme outliers for visualization (Figure 3). We used ensemble models like random forest and gradient boosting, which are robust for moderating outliers (Figures 4 and 5). Therefore, no aggressive outlier removal was applied.

4.2.2. Missing Value Imputation

The variables affected by missing values—such as total ESG risk score, environmental, social and governance risk scores, ESG percentile and controversy score—are continuous numerical measures. This approach was chosen because the affected variables are continuous ESG scores with limited missingness, and mean imputation preserves the sample size, maintains distributional consistency and ensures stable model performance without introducing additional estimation complexity. Missing values in categorical variables (address, sector, industry and description) were minimal (one observation per variable) and were therefore handled using mode imputation. Only simple imputation techniques were used. Multiple imputation techniques were not employed, as the proportion of missing data was low and the primary objective was predictive accuracy rather than parameter inference. Missing values were imputed using mean imputation, as presented in the Equation (1). Mean imputation helps to preserve the statistical integrity of the dataset and minimizes distortions in model training [16].

4.2.3. Feature Encoding

In this research, categorical and numerical variables were carefully processed to optimized for predictive modeling. Different encoding and transformation techniques were used for each feature type because the S&P 500 ESG Risk Ratings dataset included a variety of data types, such as sector information, corporate descriptors and numerical ESG indicators.

Encoding of Categorical Features: The qualitative variables known as categorical attributes (such as Industry Group, Sector and Country of Domicile) need to be transformed into a quantitative format that can be used with regression techniques. To do this, One-Hot Encoding (OHE) was used. It is represented in the Equation (2), where for a categorical feature Xc with categories C1, C2, …, Ck,

This encoding preserves the nominal nature of the categorical variables without introducing any ordinal bias. The existence of a category can thus be independently and false-association-freely interpreted by models such as random forests, gradient boosting and linear regression.

Transformation of Numerical Features: The dataset contains numerical attributes (e.g., Environmental Pillar Score, Social Pillar Score, Governance Pillar Score) too. These attributes were standardized to a common scale to ensure uniform contribution during model training. The Z-score normalization technique was applied as represented below in Equation (3), where represents the original value of the feature, represents the mean of the feature and represents the standard deviation of the feature.

4.2.4. Feature Scaling (Normalization)

For feature scaling, normalization was applied before model training. Each feature was rescaled to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This change was particularly important for algorithms that are sensitive to feature magnitude discrepancies. For example, algorithms such as Ridge/Lasso regression and support vector regression.

To guarantee a consistent scale, speed up learning and enhance convergence, the features were normalized during model training. We applied Min-Max normalization as per Equation (4), represented as follows:

This method of normalization scales the data into the range [0, 1]. Each value is transformed by subtracting the dataset’s smallest value X and dividing by the range.

4.2.5. Train–Test Split

The pre-processed dataset was partitioned into training and testing subsets using an 80:20 ratio. The random seed was fixed and maintained at a random_state value of 42. This helped to maintain reproducibility. This split allowed for a fair evaluation of predictive models on unseen data.

4.3. Model Development and Evaluation Framework

This section explains the different phases applied for model development and the framework used for evaluation. For optimal generalization prediction for a target variable total ESG risk score, state-of-the-art base regression algorithms were used. We used both tree-based ensemble methods and kernel-based regression techniques.

4.3.1. Selection of Base Machine Learning Models

Random forest regressor (RF), gradient boosting regressor (GBR), extreme gradient boosting regressor (XGBoost), support vector regressor (SVR), linear and ridge regressor are the foundational models chosen as a base models [17]. These selected models enable the framework to capture complex non-linear patterns, variable interactions and data heterogeneity.

Random Forest Regressor (RF): The random forest algorithm is a type of ensemble decision tree algorithm that operates on the principle of bagging, called bootstrap aggregation. A random selection of samples with features is used to train each tree. This helps to maintain lower values for variance and overfitting [18]. The prediction of a random forest regressor is the mean of all individual tree outputs, as described in Equation (5), where represents the prediction from the decision tree and T is the total number of trees.

Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR): In order to rectify the residual mistakes of the preceding ensemble, the gradient boosting regressor creates trees one after the other. Gradient descent in function space is used by the model to minimize a differentiable loss function [19]. At each iteration m, the model update is given by the Equation (6) described below, where is the value for the model after m iterations, is the learning rate and shows the weak learner fitted to the negative gradient of the loss function.

This approach is suitable to have a strong predictive model by successively refining errors. Furthermore, it makes the model highly suitable for complex and non-linear ESG risk relationships.

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): This is an optimized implementation of gradient boosting. It contains strategies like regularization, parallelized computation and tree pruning. These strategies are required for enhanced performance. It minimizes the following regularized objective function represented in Equation (7) [20].

Here, represents the loss function, which measures the difference between the true label and the predicted label , which defines the function for regularization term that is used to penalize the complexity of the model. K is the total number of trees used while ensembling. XGBoost balances the model’s fit and complexity, and this characteristic enables it to capture intricate ESG interdependencies during the process of generalization [20].

Support Vector Regressor (SVR): The support vector regressor is a version of the support vector machine (SVM), but based on regression. It constructs a hyperplane that fits the data within an -insensitive margin. It finds a flat function that best approximates the target value, thus minimizing complexity. It minimizes overfitting and maintains a high generalization ability [21]. It optimizes the function depicted in Equation (8):

Subject to ; and .

Here, w determines the orientation (slope) of the regression hyperplane. b adjusts the position of the regression hyperplane. represents how much the prediction for sample i exceeds the upper boundary of the -tube. represents by how much the prediction for sample i falls below the lower boundary of the -tube. represents the predictor variables for observation i, while is the true value of the dependent variable corresponding to the value represented by [22].

Linear Regression (LR): Linear regression forms the foundational model for continuous prediction tasks. Here, the assumption is to have a linear relationship between independent variables and the dependent variable. LR tries to minimize the residual sum of squares (RSS) between observed and predicted values [23]. It is represented in the form of Equation (9);

where represents the regression coefficients, represents feature values, is the actual target and is the predicted output.

Ridge Regression (RR): Ridge regression is a regularized extension of linear regression that includes an L2 penalty to mitigate multicollinearity and overfitting. It occurs in high-dimensional or correlated ESG features [24]. It is described in Equation (10), where is a regularization parameter controlling the penalty intensity.

4.3.2. Hyperparameter Tuning

When using different algorithms, such as ensemble-based and kernel-based regressors, hyperparameter tuning is crucial for improving model performance and generalization. Each model has a set of parameters that affect its flexibility, learning process and ability to balance variance and bias.

Cross-Validation Framework: In order to evaluate the reliability of performance of the model, the k-fold cross-validation strategy was incorporated. When k = 5, the training dataset was divided into 5 ‘folds’ of 5 sections. The remaining folds were used in the training dataset, and the 1 ‘hold-out’ fold was used as a validation set in each ‘last’ pass. The final performance score was determined by taking the mean of the metrics that were recorded during the five iterations. The following formula was used to determine the cross-validated root mean square error (CV_RMSE) [25].

where represents the predicted value for sample i in fold , and is the number of samples in that fold.

The cross-validated coefficient of determination CV_R2 [26] was computed as follows:

where is the mean of the actual target values in the validation fold.

Tuned Parameters for Each Model (Base Models): Table 1 shows the parameters tuned for each of the models used as a base model.

Table 1.

Tuned parameters for each base model.

Hyperparameter Tuning for Stacked Ensemble: Table 2 shows the hyperparamters tuned for the stacked ensemble models.

Table 2.

Tunable components and typical parameter ranges for stacked ensemble models, including meta-model, cross-validation, passthrough, base model selection and stacking depth.

A. Tunable Components

B. Optimization Objective

The stacking hyperparameters were tuned using a nested grid search with the objective function described in Equation (12):

Here, denotes the cross-validated RMSE computed from meta-level predictions.

The focus is on minimizing aggregated prediction error across all validation folds.

4.4. Stacked Ensemble Learning Model (Proposed Approach)

We suggest a novel stacked ensemble regression paradigm that progressively aggregates several heterogeneous learners in order to overcome the drawbacks and biases associated with predicting ESG risk scores. Conventional ensemble techniques such as bagging and boosting employ the same predictive mechanism and sequentially employ two heterogeneous or the function of heterogeneous learners. In order to represent different feature interactions between the base-learners, our suggested stacking technique investigates the prediction of several base models using meta-learning in a layer.

This study presents a two-level stacked ensemble learning framework that methodically integrates several heterogeneous regression models in order to address the complexity and non-linearity inherent in ESG risk prediction. The goal of this hierarchical ensemble is to minimize the shortcomings of each model class while maximizing their distinct learning capacities.

4.4.1. Level-0: Base-Learners (First-Layer Models)

In the Level-0 layer, six base regression models independently learn mappings between ESG features and the target variable. The set of methods was specifically selected to cover a broad range of statistical and machine learning approaches in order to allow the model to capture complicated non-linear interactions and linear dependencies.

Formally, for the training dataset, the following is applied:

Each base-learner learns the following function:

The outputs of these base models collectively form a new meta-feature matrix Z:

4.4.2. Level-1: Meta-Learner (Second-Layer Model)

The Level-1 learner, called a meta-learner, uses the base model predictions as input and learns how to weight them optimally to reduce the total prediction error.

Because the linear regression model is transparent and interpretable, it is used as a meta-learner in the ensemble model for this purpose. It learns the optimal weighted combination of base model predictions.

where represents the learned weight corresponding to the mth base model, and is the residual error term. The optimization objective for the meta-learner is

For an unseen sample , the final ensemble prediction is

The two-level stacked ensemble regression architecture, which combines a meta-learning layer with different base-learners, represents a methodological approach in predicting ESG risks. The suggested methodology outperforms traditional single-model techniques or homogeneous ensemble strategies by focusing on capturing numerous data interactions. It also helps in reducing bias and volatility and enhancing predictive generalization across a range of financial and sustainability measures.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Evaluation Metrics Used

Various evaluation metrics were used to evaluate the predictive performance of the proposed model. RMSE is the root mean square error, which measures the average magnitude of the prediction errors. Here, a lower value attached to the RMSE means the model has a better performance accuracy, measured as presented in Equation (20), where n presents the number of data points (or samples) in the dataset, refers to the actual ESG risk score and refers to the predicted ESG risk score [27].

MAE is the mean absolute error, and it measures the average absolute difference between predicted and actual values, less sensitive to large outliers, as presented in Equation (21) [28].

MAPE is the mean absolute percentage error, expressed in percentage terms. It reveals at what percentage the predictions are off from to the actual values [29]. It is calculated as per Equation (22).

Another evaluation metric used is the score, which denotes the coefficient of determination, where values closer to 1 indicate better fit. It is represented by the following Equation (23), where refers to the actual ESG risk score and predicted ESG risk score [30]:

If we used only one split of the dataset, the results might be biased. To avoid this, we used cross-validation (like k-fold CV) during the experiment to have a more reliable estimate of model performance. Therefore, we also evaluated the model’s performance using CV_RMSE_Mean, CV_RMSE_STD, CV_R2_Mean and CV_R2_STD [30].

CV_RMSE_Mean shows the average prediction error (RMSE) across all folds. It is used to compare the model results, and the one with the lowest value is generally more accurate. It is presented by Equation (24), where k is the number of folds in k-fold cross-validation and j is the index of the fold (from 1 to k).

CV_RMSE_STD represents the standard deviation of the RMSE across all k-folds. It helps to determine if the model is stable or consistent across folds, represented by Equation (25).

To determine the average explanatory power of the model, is used. It represents the average score across all k-folds and is represented by Equation (26).

To measure how much the varies, is used. Here, a lower value represents a better performance or indicates that the model is more stable compared to the other models. It is the standard deviation of the scores across all folds, and is represented by Equation (27).

5.2. Performance of the Models

The stacked ensemble performed better with respect to predictive performance, with the lowest root mean square error (RMSE = 1.006), mean absolute error (MAE = 0.664) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE = 3.13%), as well as the highest coefficient of determination ( = 0.979) and explained variance (0.979), thus demonstrating almost full variance coverage and low bias (Table 3 and Table 4). This performance is further supported by the results of the cross-validation, with a CV_RMSE_Mean of 1.383, of 0.957, coefficient of variation () of 0.0196 and (CV_RMSE_STD) of 0.3617, which indicate strong predictive power with only slightly high inter-fold variability. Comparatively, the LightGBM and gradient-boosted decision trees had values of about 0.965 and 0.962, respectively, and MAPE values of 3.5% to 3.9%. Random forest and XGBoost had a slightly higher error but competitive performance. The linear regressors, on the other hand, such as ordinary least squares and ridge regression, showed poor fit, with values close to 0.55 and RMSEs close to 4.68. Finally, support vector regression performed the worst, with its close to 0.02 and RMSE close to 6.93, which even further supports the idea that support vector regression does not fit the data well.

Table 3.

Performance of regression models predicting the total ESG risk score on the test set, reporting RMSE, MAE, MAPE, , explained variance and 5-fold cross-validated RMSE and (mean ± SD).

Table 4.

Performance of regression models predicting the environment, social and governance data score on the test set, reporting RMSE, MAE, MAPE, R2, explained variance and 5-fold cross-validated RMSE and R2 (mean ± SD).

5.3. Error Distribution and Model Calibration Assessment

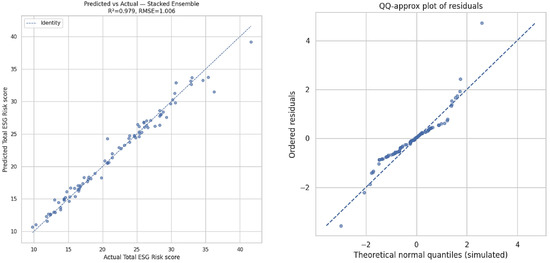

The correlation in Figure 3 is nearly linear, the bias is negligible and the error in prediction is small compared to the range. The QQ-approximation plot shows that the residuals are in the neighborhood of the normality in the central quantiles, but have a mild positive skew and long right tail, which can be explained by a small number of light predictions of high-risk cases. Overall, the diagnostic measures testify high-quality calibration and accuracy, and the deviations are due mainly to extreme values.

Figure 3.

Predicted vs. actual and QQ-approx residual plot for the stacked ensemble, showing model calibration and modest right-tail deviation from normality.

5.4. Comparative Explanatory Power of Regression Models

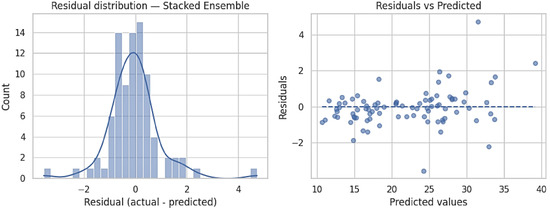

The distribution of the residuals (Figure 4) is narrowly centered around zero, which is expected given the high performance of the model ( = 0.979, RMSE = 1.006), and means that there is a minor systematic bias; the histogram/KDE reflects a single asymmetrically positive mode with a small number of extreme positive values, reflecting a slight violation against the normal distribution. The scatter plot of the residuals vs. predicted values (Figure 4) shows that there is no non-linear trend, which indicates that there is no significant model misspecification, and variance shows slight growth in some larger predicted values, with some outliers that indicate occasional underprediction. On the whole, the diagnostic analysis supports a well-calibrated tree ensemble that has low heteroscedasticity.

Figure 4.

Residual diagnostics for the stacked ensemble: histogram with KDE of residuals (left) and residuals versus predicted values (right), showing centered errors with limited heteroscedasticity and a few outliers.

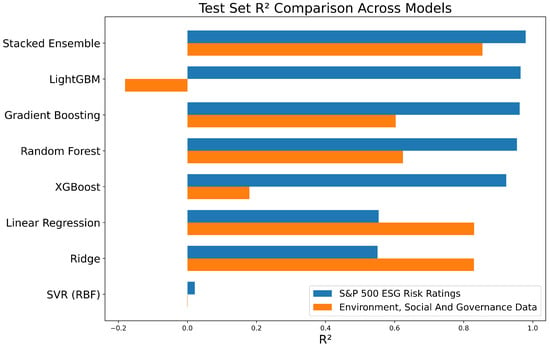

The comparison of the test-set of the models for the S&P 500 ESG Risk Ratings dataset indicates that the stacked ensemble has the highest explanatory power ( = 0.979), followed by LightGBM and gradient boosting ( = 0.960–0.965), and finally random forest and XGBoost ( = 0.92–0.95) (Figure 5). Linear regression and ridge provide more moderate fits ( = 0.55), and SVR does not work well ( = 0.02). Furthermore, for the environmental, social and governance data, the test-set of the stacked ensemble has the highest explanatory power ( = 0.854), followed by linear regression and ridge ( = 0.803–0.829). These results indicate that non-linear tree-based ensembles are much better at capturing the target structure as compared to linear or kernel methods on the target dataset (which satisfies H3).

Figure 5.

Test-set by model, showing superior variance explanation by tree-based ensembles (stacked, LightGBM, GBM) relative to linear and kernel methods.

5.5. Cross-Validation Results Confirming Model Stability

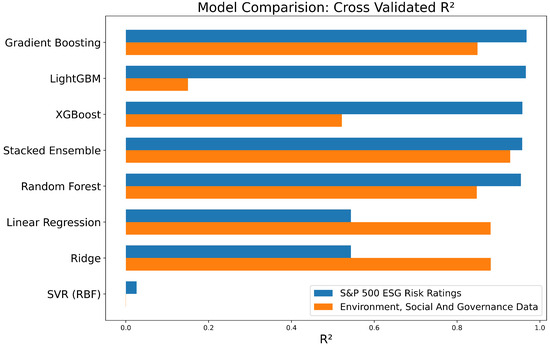

Concerning the cross-validated , the tree-based ensembles significantly outperform the linear and kernel methods. In the S&P 500 ESG Risk Ratings dataset, gradient boosting has the best mean cross-validated , with the highest value of 0.968 ± 0.007, and LightGBM and XGBoost have similar results of 0.966 and 0.958, respectively (Figure 6). The stacked ensemble and random forest have the strongest predictive abilities, with mean values of 0.954 to 0.957 and standard deviations of 0.005 to 0.020, which reflects consistent prediction through the cross-validation folds. Linear regression and ridge regression, on the contrary, attain moderate accuracy ( = 0.544 ± 0.13–0.14), whereas support vector regression shows very low explanatory accuracy ( = 0.03 ± 0.15). In the environmental, social and governance data, stacked ensemble has the best mean cross-validated , with the highest value of 0.9285. The overall finding of these results is that non-linear tree ensembles give significantly better and more stable predictive performance.

Figure 6.

Cross-validated (mean ± SD) for each regression model, highlighting superior and stable performance of tree-based ensembles versus linear and kernel methods.

5.6. Feature Importance and Correlation Insights

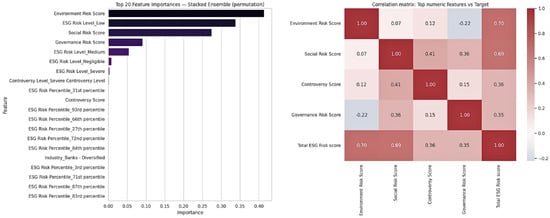

Correlation analysis (Figure 7) indicates strong positive associations between environmental and total ESG risk scores (r nearly to 0.70) and between social and total ESG risk scores (r nearly to 0.69), while governance exhibits weaker correlations with the composite score. Because the ESG component scores are partially correlated by construction, their feature importance values should be interpreted as indicators of predictive contribution rather than as causal effects.

Figure 7.

Permutation-based top-20 feature importances (left) and Pearson correlations among the top numeric features and the total ESG risk score (right).

The permutation importance and correlation analysis stacked ensemble shows that model predictions are mostly driven by environmental and social parts (Figure 7). Stacked ensemble permutation importance and correlation analysis suggest that risk scores predominantly dictate predictions because of the environmental and social components (Figure 7). Out of the predictors, the environmental risk score incrementing value at 0.41 exhibits the highest permutation importance. This is followed by the ESG_Risk_Level_Low indicator at 0.37 and social risk score at 0.32. Most features, based on their percentiles, and categorical indicators aligned with negligible or severe risk levels add very little to the overall predictive contribution. Correlation analysis shows that environmental and total ESG risk scores positively correlate to each other (r = 0.70), as well as social and total ESG risk scores (r = 0.69). In the social component, controversy score has a moderate correlation with social score (r = 0.41), as well as with the total composite ESG score (r = 0.36). It can be noted that the governance variables present a relatively weaker correlation overall. This includes a total moderately positive correlation with total ESG Rrisk of 0.35 and a slight negative correlation with environmental risk of −0.22.

These results show that the model draws considerably from environmental and social signals, which are structurally and statistically related to the composite ESG score. As a result, the ESG score correlates significantly with predictive values, but not independently. In the ESG component score and the composite ESG score, we observed strong statistically significant relationships, indicating potential multicollinearity, and we explain these potential relationships with the shared predictive power in the other features. Therefore, we must be more cautious with the ESG component scores when we explain the model predictions.

The multicollinearity among the sub-components and the ESG risk score is not an statistical issue but an issue with the structural characteristics in ESG measurement. Since the total ESG score is totalled as the sum of the environmental, social and governance dimensions, we expect a strong correlation between the values of the components and the composite. In predictive analysis, this multicollinearity means that the explanatory power is divided among the features that are correlated, and this can affect the permutation importance values as compared to the predictive power. Therefore, the importance of the components should be seen as the contribution of the components to the prediction as a whole, and not as an individual, causal predictions.

5.7. Practical Implications

Investors, asset managers, risk officers and regulators may operationalize the predictive model to improve ESG screening, prioritize due diligence and make capital allocation or engagement decisions. The stacked ensemble, our leading predictor (RMSE = 1.006 and 1.3272; MAE = 0.664 and 1.1123; MAPE = 3.13% and 1.95%; = 0.979 and 0.854; explained variance = 0.979 and 0.854; for both datasets), has sufficient predictive error to rank firms reliably in portfolios and activate an investigator response. Analyses of diagnostics indicate residuals that are centered around zero with a small right skew, a few high-risk underpredictions and moderate heteroscedasticity; therefore, automated flags of high predicted scores should lead to personal review. The environment component (importance = 0.41), ESG risk level (importance = 0.37) and social component (importance = 0.32) are shown to be the most important drivers, with strong correlations (Environment–Total = 0.70 and Social–Total = 0.69). Possible multicollinearity, though, should be considered when explaining the effects of individual features. All in all, the combination of the human oversight of outliers and the model has the potential to dramatically improve screening throughput and consistency, improve early risk detection and facilitate evidence-based stewardship and regulatory reporting.

5.8. Comparative Performance with Prior Studies

Table 5 illustrates the wide range of R2 values found in the literature [31,32,33,34,35], which can be attributed to variations in evaluation frameworks, target variables, feature construction and data sources. While more recent studies that use ensemble methods or optimized learning strategies typically achieve higher R2 values, earlier research typically reports moderate levels of predictive performance. In this regard, the suggested two-level stacked ensemble shows a comparatively high R2 on the S&P 500 dataset, indicating a strong explanatory capacity for ESG risk prediction in the sample under analysis.

Table 5.

Comparative performance with prior ESG prediction studies.

Because ESG scores are provider-specific and influenced by various aggregation techniques and reporting practices, it is crucial to remember that direct numerical comparisons between studies should be interpreted cautiously. Therefore, rather than establishing a rigid ranking of approaches, this comparison is meant to provide contextual insight into model performance.

5.9. Firm-Level Illustrative Explanation and Decision Usefulness

To show how decision usefulness works at the firm level, imagine a large S&P 500 company that the model flags as having a high overall ESG risk. This assessment is largely driven by elevated environmental risk, which stems from the company’s involvement in carbon-intensive operations and a history of recent environmental controversies. Social factors also play a noticeable role, with issues such as employee safety and supply chain management contributing moderately to the risk profile. Governance, on the other hand, has a smaller impact on the overall score, which is typical for large, mature firms that tend to have more standardized governance structures in place.

This type of firm-specific explanation helps investors and risk managers better understand why a company is labeled as high-ESG-risk. Rather than relying solely on a single, aggregated score, they can see which ESG components are driving this risk and tailor their responses accordingly—whether that means prioritizing environmental improvements or keeping a closer watch on social-related challenges.

6. Conclusions

The most important observation is that environmental and social aspects have a greater effect than governance in predicting ESG risk. This trend points to the systemic traits of construction of an ESG score such as what the data is, how the data is disclosed and how the data is aggregated, rather than to empirical standards of sustainability. The stacked ensemble approach used in this study shows predictive power on total ESG risk among S&P 500 companies, with a significant enhancement in predictive accuracy compared to single-model control groups, and provides interpretable features that can be used to identify the role of environmental and social factors. These results support the realistic application of ensemble-based models to scalable ESG screening and prioritization during investment processes when extreme or outlier predictions can be assessed by experts. Given the presence of correlated ESG components, feature importance results are interpreted as reflecting predictive relevance rather than independent causal influence, reinforcing the need for cautious use of model explanations in ESG decision-making. The methodological limitations include the possible existence of multicollinearity of component scores, as well as reliance on cross-sectional inputs; future studies should incorporate temporal dynamics, non-financial data alternatives, causation attribution methods and multi-provider harmonization to help reduce rating divergence. Overall, this framework provides a viable and explicit addition to the currently existing ESG assessment practices, although it is the kind that must be used as a complement to, but not a replacement of, qualitative judgment and domain oversight.

From a conceptual point of view, the existence of multicollinearity among ESG components points to a more general problem in designing and interpreting ESG scores. Aggregation of ESG metrics combines redundant information across the environmental, social and governance components, which may conceal the true value of each pillar. While this does not affect the predictive power of a given machine learning model, it does call for careful consideration of the contradictions in each component and reiterates in the ESG literature the necessity for more granular ESG reporting. These results suggest to practitioners and data providers that component disclosure along with tiered aggregation may enhance the comparability and utility of ESG scores.

The analysis used to derive these results is focused on S&P 500 firms, which are large, publicly traded corporations and are more likely to have fully developed disclosure requirements, as well as regulatory oversight. This, however, limits the findings’ generalizability to other populations of firms. Other population segments such as small companies, privately owned firms and businesses in emerging economies can exhibit signficantly different practices in ESG reporting, as well as variance in openness, regulatory constraints and reporting guidelines. This is also true in the construction and understanding of ESG scores, as again, there are varying degrees of sustainability reporting rules and practices in different countries.

A single snapshot of ESG risk across businesses is provided by the cross-sectional data used in this study’s empirical analysis. As a result, the model is designed for contemporaneous ESG risk assessment rather than temporal or forward-looking prediction. However, the proposed stacked ensemble architecture can be readily expanded to include panel datasets. Future research could employ rolling-window training schemes, lagged ESG component scores and time-aware cross-validation to capture ESG changes and assess predictive stability over time. These extensions would allow for longitudinal ESG risk modeling while preserving the analytical framework proposed in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and A.N.; Methodology, S.P., A.N. and P.D.; Software, S.P. and A.N.; Validation, S.P., A.N. and P.D.; Formal analysis, S.P., A.N. and P.D.; Investigation, S.P., A.N. and P.D.; Resources, S.P. and A.N.; Writing—original draft, S.P., A.N. and P.D.; Writing—review and editing, S.P., A.N. and P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the kaggle data repository at on 12 October 2025 https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/pritish509/s-and-p-500-esg-risk-ratings and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tunguz/environment-social-and-governance-data [14,15].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance |

| S&P 500 | Standard & Poor’s 500 Index |

| ML | Machine learning |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination (R-squared) |

| CV | Cross-validation |

| k-fold | k-fold cross-validation |

| CV_RMSE_Mean | Mean cross-validated RMSE |

| Mean cross-validated R2 | |

| LightGBM | Light gradient boosting machine |

| GBM | Gradient boosting machine |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| SRI | Socially responsible investment |

| EU | European Union |

| KDD | Knowledge discovery and data mining |

| ACM | Association for Computing Machinery |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

References

- Apergis, N.; Poufinas, T.; Antonopoulos, A. ESG scores and cost of debt. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. Improving ESG Scores with Sustainability Concepts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M. Analyzing Contemporary Trends in Sustainable Finance and ESG Investment. Law Econ. 2023, 2, 44–52. Available online: https://www.paradigmpress.org/le/article/view/867 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, G.M.; Savio, R.; Paolone, F.; Tiscini, R. The CSR committee as moderator for the ESG score and market value. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3231–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarelli, M.; Cosimato, S.; Landi, G.; Iandolo, F. Socially responsible investment strategies for the transition towards sustainable development: The importance of integrating and communicating ESG. TQM J. 2021, 33, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, S.S.; Withana, P.A.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Sarkar, B.; Chopra, S.S.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Scoring environment pillar in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assessment. Sustain. Environ. 2021, 7, 1960097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. The use of ESG scores in academic literature: A systematic literature review. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumrose, M.; Rink, S.; Eckert, J. Disaggregating confusion? The EU Taxonomy and its relation to ESG rating. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 48, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, F. Can heterogeneous environmental policies mitigate ESG divergence?—Based on corporate green innovation and bleaching green behavioral options. Sustain. Future 2024, 8, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binzaiman, F.; Edhrabooh, K.M.; Alromaihi, M.; AlShammari, M. Predicting Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores with Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Data Analysis and Business Intelligence (ICDABI 2024), Zallaq, Bahrain, 23–24 October 2024; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Byrne, J.G.D.; Christiaen, C. Breaking the ESG rating divergence: An open geospatial framework for environmental scores. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Agarwal, S. Applications of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Sector. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Optimization Techniques and Future Engineering, Tamilnadu, India, 23–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepetis, A.; Rizos, F.; Pierrakos, G.; Karanikas, H.; Schallmo, D. A Sustainable Model for Healthcare Systems: The Innovative Approach of ESG and Digital Transformation. Healthcare 2024, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritish509. S&P 500 ESG Risk Ratings; Kaggle Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/pritish509/s-and-p-500-esg-risk-ratings (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Tunguz, B. Environment, Social and Governance Data; Kaggle Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tunguz/environment-social-and-governance-data (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Nijman, S.W.J.; Groenhof, T.K.J.; Hoogland, J.; Bots, M.L.; Brandjes, M.; Jacobs, J.J.L.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Moons, K.G.M.; Debray, T.P.A. Real-time imputation of missing predictor values improved the application of prediction models in daily practice. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhijani, P.; Nath, A.; Vakani, H.; Mistry, M.; Koradiya, H.; Jayswal, H.S.; Chaudhari, J.P.; Patel, A.; Dubey, N. Lime Diseases Classification Using Machine Learning and Spectrometry. In Information Systems for Intelligent Systems, ISBM 2024; Londhe, N.S., Bhatt, N., Kitsing, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J. Regional hydrological frequency analysis at ungauged sites with random forest regression. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, O.; Schelter, S.; de Rijke, M. Probabilistic Gradient Boosting Machines for Large-Scale Probabilistic Regression. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD 2021), Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1510–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, B.; Homaifar, A.; Girma, A.; Karimoddini, A.; Opoku, D. XGBoost: A tree-based approach for traffic volume prediction. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC 2021), Melbourne, Australia, 17–20 October 2021; pp. 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; O’Donnell, L.J. Chapter 7—Support vector regression. In Machine Learning; Mechelli, A., Vieira, S.B.T.-M.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Rastogi, R.; Chandra, S. A class of new Support Vector Regression models. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 94, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, A.; Kumar, A.; Vyas, S. Comparative Study of Proposed linear regression algorithm to Scikit-Learn Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON 2023), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 1–3 December 2023; pp. 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magklaras, A.; Gogos, C.; Alefragis, P.; Birbas, A. Enhancing Parameters Tuning of Overlay Models with Ridge Regression: Addressing Multicollinearity in High-Dimensional Data. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, A.N.; Michalak, K.; Giacobini, M. Cross-Validation Approach to Evaluate Clustering Algorithms: An Experimental Study Using Multi-Label Datasets. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, S. Cross-Validation, Risk Estimation, and Model Selection: Comment on a Paper by Rosset and Tibshirani. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2020, 115, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, S.; Sudiarso, A.; Herliansyah, M.K. The Accuracy Measurement of Stock Price Numerical Prediction. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1569, 032027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Ma, J. A Novel Stacked Generalization Ensemble-Based Hybrid SGM-BRR Model for ESG Score Prediction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauf, M.F.; de los Campos, G.; Munilla, S. Comparing Genomic Prediction Models by Means of Cross Validation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 734512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Hsu, B.-W. Empirical Study of ESG Score Prediction through Machine Learning—A Case of Non-Financial Companies in Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayyad, M.; Fadel, S.M. Predicting ESG Scores Using Firms’ Financial Indicators: A Machine Learning Regression Approach. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Predicting Corporate ESG Scores Using Machine Learning: A Comparative Study. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 118, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krappel, T.; Bogun, A.; Borth, D. Heterogeneous Ensemble for ESG Ratings Prediction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Wang, J.; Zeng, C. An Optimized Machine Learning Framework for Predicting and Interpreting Corporate ESG Greenwashing Behavior. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.