Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) and other foundation models are rapidly being woven into enterprise analytics workflows, where they assist with data exploration, forecasting, decision support, and automation. These systems can feel like powerful new teammates: creative, scalable, and tireless. Yet they also introduce distinctive risks related to opacity, brittleness, bias, and misalignment with organizational goals. Existing work on AI ethics, alignment, and governance provides valuable principles and technical safeguards, but enterprises still lack practical frameworks that connect these ideas to the specific metrics, controls, and workflows by which analytics teams design, deploy, and monitor LLM-powered systems. This paper proposes a conceptual governance framework for enterprise AI and analytics that is explicitly centered on LLMs embedded in analytics pipelines. The framework adopts a three-layered perspective—model and data alignment, system and workflow alignment, and ecosystem and governance alignment—that links technical properties of models to enterprise analytics practices, performance indicators, and oversight mechanisms. In practical terms, the framework shows how model and workflow choices translate into concrete metrics and inform real deployment, monitoring, and scaling decisions for LLM-powered analytics. We also illustrate how this framework can guide the design of controls for metrics, monitoring, human-in-the-loop structures, and incident response in LLM-driven analytics. The paper concludes with implications for analytics leaders and governance teams seeking to operationalize responsible, scalable use of LLMs in enterprise settings.

1. Introduction

Enterprise analytics is changing character. For many years, analytics teams focused on well-bounded predictive models, reports, and dashboards. Today, large language models (LLMs) and other foundation models act as general-purpose engines for generating text, code, and explanations across a wide range of analytic tasks [1]. In a single workflow, an LLM might help clean data, draft SQL queries, generate scenarios, and narrate results for executives. From a distance, this looks like a straightforward upgrade to analytics tooling. Up close, it raises a harder question: how do we govern these systems so that they serve organizational aims reliably and responsibly?

Research on foundation models has drawn attention to their dual nature as powerful enablers and concentrated sources of risk [1]. Work on the “stochastic parrots” problem highlights how large language models can reproduce and amplify data issues, consume significant resources, and remain opaque even to their creators [2]. These scholars emphasize that LLMs can produce fluent, persuasive language by recombining patterns from training corpora without grounding or intent, which increases the risk of confidently stated errors (‘hallucinations’) and untraceable bias amplification in downstream decisions, especially when outputs are used as analytic evidence rather than as drafts. Complementary risk mapping for language models catalogues harms such as discrimination, misinformation, malicious use, and human–computer interaction failures that are directly relevant to analytics in high-stakes domains [3]. Surveys of bias and fairness in machine learning show how such harms can cascade from data through models into downstream decision processes [4].

In parallel, the AI alignment literature explores what it means for AI systems to act in accordance with human values, organizational objectives, and broader societal norms [5]. Alignment is not only a technical issue of training objectives or reward shaping; it is also a normative issue of whose preferences and values are embedded and how they are negotiated. Organizational AI governance research responds by proposing ways to translate high-level ethics principles into operational practices. The Hourglass Model frames AI governance as a traceability mechanism that narrows from high-level principles to a “waist” of standardized organizational processes and controls (e.g., documentation, accountability, review gates), and then expands outward into application-specific operational artifacts (e.g., use-case requirements, monitoring procedures). This “narrow waist” is intended to prevent ethics-and-policy commitments from remaining aspirational by translating them into repeatable controls that can be audited and maintained across deployments [6]. The high-level ethical principles are operationalized through mid-level organizational processes and then translated into concrete technical artifacts. We position our framework as complementary: it preserves this translation logic while specifying how it manifests in analytics teams’ daily objects, pipelines, BI tooling, KPIs, incident runbooks, and audit trails. Work on algorithmic accountability offers end-to-end internal auditing procedures for AI systems [7], while recent proposals for auditing LLMs advocate structured approaches that distinguish governance, model, and application audits [8]. Broader ecosystem perspectives emphasize that AI governance does not stop at the organizational boundary; it connects firms, regulators, and civil society in interdependent networks [9,10].

Enterprise analytics teams sit at the intersection of these debates. On one side, they are tasked with delivering measurable business value through models, dashboards, and decision-support tools, often under tight timelines and with heterogeneous legacy systems. On the other side, risk, compliance, and internal audit functions increasingly expect analytics to conform to emerging AI governance norms, regulatory requirements, and internal standards of fairness and accountability. Existing alignment and governance frameworks offer important building blocks, but they rarely speak in the language of day-to-day analytics work: data pipelines, feature stores, business intelligence platforms, machine learning operations (MLOps), deployments, key performance indicators (KPIs), and service-level agreements, in ways that resemble accumulated “hidden technical debt” in real-world ML and analytics systems and require an explicit risk-management posture, particularly in regulated environments [11,12].

In enterprise analytics, governance challenges rarely appear as abstract ethical dilemmas; they surface as repeatable failure modes that directly distort decision-making. At the model level, LLMs can produce fluent but unsupported analytic narratives (e.g., invented drivers, fabricated evidence, overstated confidence), and they may reproduce social biases embedded in training data—especially when outputs are used as interpretive “analysis” rather than as drafts [2,4]. At the system level, risk is frequently created not by the base model alone but by how it is embedded into analytics workflows—prompt libraries, retrieval augmentation, tool use, and human review loops—where small design choices can generate new security and accountability gaps [7,8]. At the ecosystem level, organizations must reconcile vendor opacity and third-party dependencies with requirements for auditability, change control, and defensible decision processes—shifting governance from “best practice” to operational necessity [6,9,10]. These challenges explain why enterprises need governance that is measurable (acceptance criteria), operational (monitoring and incident response), and auditable (repeatable artifacts), rather than governance that exists only as policy. LLM-powered analytics makes this tension sharper. When LLMs summarize complex data, propose forecasts or scenarios, generate code, or interact directly with analysts and decision-makers, their outputs can quietly shape strategic and operational choices [1,3]. Yet traditional model risk management, designed for relatively static predictive models, struggles with the fluidity of LLMs: prompt sensitivity, context-window limitations, tool-using agents that call external APIs, and frequent model updates. In the absence of such clarity around the alignment checks and governance processes, it is hard for engineering and technical teams to be confident that the model is truly ready for deployment at scale. Without a solid governance approach that explicitly connects models to metrics, organizations risk shipping analytics that perform well in narrow tests but drift away from their stated objectives, risk appetite, or stakeholder expectations. And, we see organizations becoming stuck in a kind of “GenAI theatre”, where pilots and prototypes proliferate but struggle to translate into durable value in their enterprise AI and analytics initiatives. In this sense, “GenAI theatre” refers to early deployments that generate visible excitement but lack the workflow integration, metrics, and governance needed to mature into production analytics.

This paper addresses that gap by proposing a governance framework for enterprise AI and analytics that is centered on LLMs embedded in analytics workflows. The framework is organized around three layers. The model and data alignment layer focuses on how training data, evaluation datasets, prompt templates, and safeguards shape LLM behavior and analytic performance. The system and workflow alignment layer examines how LLMs are integrated into analytics pipelines, user interfaces, and decision workflows, including human-in-the-loop structures and fallback mechanisms. The ecosystem and governance alignment layer considers how enterprise analytics practices connect to organizational structures, risk and compliance processes, and external regulatory and societal expectations.

Building on prior work in AI alignment, organizational AI governance, and algorithmic auditing [5,6,7,8], the framework aims to be both conceptually coherent and practically usable. Rather than treating alignment and governance as add-on constraints, we frame them as design choices that can be reflected directly in analytics metrics, documentation, and workflows.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. First, whereas principle-to-practice governance models (e.g., “hourglass” translations) emphasize moving from ethical principles to organizational processes, we anchor governance in the operational objects analytics teams actually manage—models, systems, and metrics—so governance can be evidenced through artifacts already used in production analytics (evaluation packs, monitoring dashboards, runbooks) [6]. Second, relative to internal algorithmic auditing and layered LLM auditing proposals, we make explicit that enterprise analytics risk is produced across three loci: model behavior, workflow/system integration, and ecosystem constraints; accordingly, we specify how controls and accountability should be distributed across these tiers rather than concentrated at “the model” [7,8]. Third, we formalize governance as a bidirectional loop: ecosystem requirements (policy, regulation, risk appetite) constrain system design and model choices, while system and model behavior generate measurable evidence that must feed governance decision cycles [9,10]. The novelty is therefore not a new governance “buzzword,” but an integration that makes existing governance ideas actionable and auditable in the everyday reality of enterprise analytics. Taken together, these contributions motivate the framework’s emphasis on operational evidence—metrics and artifacts—rather than governance as policy alone. Accordingly, this manuscript is a conceptual, theory-building contribution rather than an empirical validation study. The metrics introduced are intended as governance constructs—categories of measurable indicators and auditable evidence that organizations can instantiate locally—rather than standardized or fully operationalized quantitative evaluation instruments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative, conceptual research design aimed at developing a governance framework that is grounded in existing scholarship yet closely aligned with the realities of enterprise analytics practice. The research process comprised four stages: literature review, expert consultations, framework development, and analytical evaluation with practice-based illustrations. The goal is not to estimate statistical effects, but to construct a structured lens that can guide design and governance decisions for LLM-powered analytics systems.

2.2. Literature Review

The first stage involved a targeted review of research and technical reports in four areas. The foundation-model and LLM literature provided a baseline understanding of capabilities, limitations, and systemic risks [1,2]. Work mapping ethical and social risks of language models contributed detailed harm taxonomies relevant to analytics [3], while surveys of bias and fairness in machine learning informed our understanding of how such risks propagate through data and models [4].

To connect these technical perspectives to organizational practice, we reviewed philosophical work on AI alignment [5], organizational AI governance models such as the Hourglass framework [6], ecosystem-oriented views of AI governance [9], and end-to-end algorithmic auditing approaches [7]. Recent proposals for auditing LLMs offered a starting point for thinking in terms of layered assessments [8]. The review followed an iterative process, combining database searches with backward and forward citation chasing around these anchor works.

Existing governance and auditing frameworks offer essential foundations, but they leave gaps that become pronounced in LLM-enabled analytics workflows. Principle-to-practice models can under-specify how to define acceptance criteria and measurable evidence when behavior is highly context-sensitive (prompting, retrieval, and frequent updates) [6]. Internal algorithmic auditing frameworks clarify accountability and documentation expectations but can underweight how LLM risk is often workflow-generated—through prompt libraries, tool use, retrieval pipelines, and interactive interfaces—where governance requires continuous monitoring and change control rather than one-time review [7]. Layered LLM auditing proposals provide a useful decomposition for assessment, yet they are not explicitly centered on the operational realities of enterprise analytics—data pipelines, BI systems, KPI regimes, and SLAs—where governance must be sustained and repeatedly evidenced over time [8]. Finally, ecosystem governance perspectives correctly emphasize distributed responsibility across institutions and vendors but often leave open how analytics teams translate ecosystem requirements into concrete controls and artifacts [9,10]. These limitations motivate our analytics-centered tiering and the explicit mapping from tiers to operational artifacts and metrics.

2.3. Expert Consultations

To increase practical validity and reduce purely armchair theorizing, we conducted expert consultations with practitioners who have direct accountability for LLM-enabled analytics, governance, or assurance activities. We used purposive sampling to recruit respondents with hands-on responsibility for at least one of: (i) LLM/GenAI deployment in analytics workflows; (ii) data and analytics platform engineering and MLOps; and (iii) risk, compliance, legal, privacy, or internal audit functions overseeing analytics and AI systems. Semi-structured consultation is appropriate when the goal is to elicit domain constraints, governance pain points, and control expectations while allowing cross-role comparability through a shared guide [13].

We conducted 45 consultations between May 2024 and May 2025, each lasting 15–30 minutes, via video call. To preserve confidentiality, we report only aggregated participant characteristics in Table 1 and avoid naming firms. The interview guide covered: (1) LLM use cases in analytics; (2) perceived governance and risk failure modes; (3) current control practices (documentation, testing, monitoring, approval gates); (4) auditability expectations; and (5) missing artifacts and metrics needed for scale. The consultations informed the identification of recurring themes, tensions, and practical constraints that any usable framework would need to respect, including pressure to deliver quick wins, fragmentation of accountability across functions, and difficulty integrating LLMs into existing model risk management processes. All experts interviewed were adult professionals. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent to participate was obtained verbally from all participants prior to the consultations.

Table 1.

Expert consultation participant profile.

Consultation interviews were not recorded. Notes were taken during the conversations and analyzed using thematic analysis, iterating from open coding to higher-order themes and mapping themes to the paper’s three governance tiers (model–system–ecosystem) [14]. We followed established guidance for qualitative rigor, including transparent reporting of sampling, setting, researcher roles, and analysis choices, and used the COREQ checklist as a reporting scaffold [15]. We continued consultations until the set of governance-relevant themes stabilized (pragmatic saturation) [16]. Two authors independently reviewed the coded theme structure and resolved discrepancies through discussion, maintaining an audit trail of coding decisions.

As described in Table 2, across roles, experts consistently emphasized: (T1) traceability gaps between model behavior, prompts and tooling, and downstream business decisions; (T2) measurement debt, in which success metrics are defined post hoc rather than as pre-deployment acceptance criteria; (T3) security and data-leakage risks (e.g., prompt injection, insecure output handling, sensitive data exposure) amplified by LLM integration into enterprise systems; (T4) operational ownership ambiguity regarding who is responsible for hallucinations, drift, or policy violations in analytics outputs; (T5) the need for standard artifacts (model and system cards, prompt registries, evaluation packs, monitoring dashboards, incident runbooks) to make governance auditable; and (T6) the importance of ecosystem controls (vendor risk, procurement requirements, third-party logging, and cross-functional review) before scaling beyond pilots. These themes directly informed (i) the placement of controls across the three governance tiers and (ii) the proposed “models-to-metrics” artifacts described in Section 3.2.

Table 2.

Consultation themes mapped to governance tiers.

2.4. Framework Development

The third stage focused on framework development. We began by extracting and clustering concepts from the literature and expert consultations that appeared particularly relevant to governing LLM-based analytics: alignment objectives, risk categories, governance principles, life-cycle stages, audit artifacts, and ecosystem relationships [3,4,5,6,7,8].

We then organized these clusters into three layers that mirror how LLMs appear in enterprise analytics practice. The model and data alignment layer concentrates on model behavior, training and evaluation data, and prompt design. The system and workflow alignment layer concentrates on integration into pipelines, interfaces, and human workflows. The ecosystem and governance alignment layer concentrates on organizational roles, policies, and external expectations. Iterative refinement involved mapping each conceptual element to concrete analytics activities, such as evaluation, monitoring, escalation, and documentation, and adjusting the definitions until the layers collectively formed a coherent narrative.

2.5. Analytical Evaluation and Practice-Based Illustration

In the fourth stage, we evaluated and refined the emerging framework through a combination of analytical criteria and practice-based illustration. Following guidance on designing conceptual articles and evaluating theory for design and action [17,18,19], we first assessed the framework against four criteria: internal coherence (whether the layers are logically consistent with one another), distinctiveness (whether each layer captures something meaningfully different), completeness (whether the layers collectively cover the main governance concerns surfaced in the literature and expert consultations), and usefulness (whether the framework generates concrete questions and artifacts that practitioners could reasonably act on).

We then subjected the framework to practice-based illustration using composite scenarios. These scenarios were constructed by synthesizing patterns that appeared across expert consultations and publicly available descriptions of LLM deployments in analytics contexts, for example, narrative generation for customer analytics, internal risk analytics assistants, and decision-support tools. Rather than aiming for statistical or case-study generalization, this step followed an analytic generalization logic [17,18], asking whether the framework could be systematically applied to these scenarios, whether it highlighted governance issues that matched practitioners’ concerns, and whether its layers suggested differentiated, actionable interventions. Insights from this exercise fed back into several rounds of refinement of layer boundaries, terminology, and example artifacts.

As the aim of this research is theory building grounded in real-world practice rather than empirical hypothesis testing or statistical validation, the primary contribution is a conceptual governance framework. Accordingly, our evaluation emphasizes analytic generalization: clarifying the conditions under which particular control placements and evidence pathways should be expected to hold, rather than claiming statistical generalizability from a sample of firms [17]. To strengthen practical credibility, we complement the framework with expert consultations and scenario-based application traces, and we specify measurable indicators and auditable artifacts (Section 3.2). We also outline a staged empirical research agenda for future work, including: (i) within-organization adoption studies examining whether the toolkit improves documentation completeness, monitoring coverage, and incident responsiveness; (ii) comparative multi-site case studies to test boundary conditions across sectors and risk profiles; and (iii) longitudinal analyses tracking governance performance across model updates and workflow changes.

3. Results

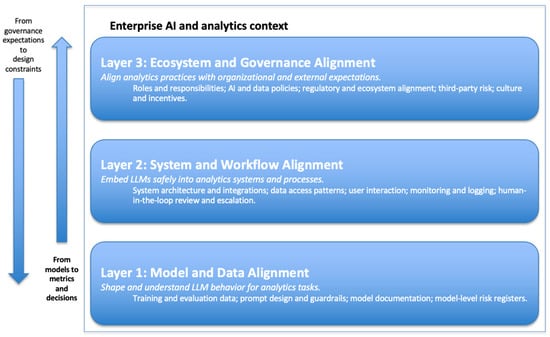

In theory-building research of such kind, “results” take the form of a structured framework rather than numerical findings. This section, and Figure 1 below, presents the three-layered governance framework and illustrates its use in enterprise analytics scenarios.

Figure 1.

Three-Layer Governance Framework for LLM-Powered Enterprise Analytics.

3.1. Three-Layered Governance Framework

In many enterprises, the journey from an LLM to business value follows a familiar path. Models are selected, tuned, or accessed through APIs; systems and applications wrap these models into tools for analysts and business users; metrics and dashboards track performance, usage, and outcomes; and governance processes periodically review and recalibrate all of the above. Our central proposition is that governance for LLM-powered analytics should be organized along the same path. Instead of treating governance as an external checklist, the framework embeds it directly into the structures that analytics teams already manage: models, systems, and metrics.

The framework is organized into three layers: model and data alignment, system and workflow alignment, and ecosystem and governance alignment. The model and data alignment layer focuses on how the LLM behaves on relevant tasks, given its training data, evaluation data, and prompt configuration. The system and workflow alignment layer examines how the model is integrated into analytics pipelines, interfaces, and decision workflows, including the design of human-in-the-loop processes. The ecosystem and governance alignment layer considers how analytics practices reflect organizational structures, policies, risk appetite, and external regulations and norms [6,9].

Information in this framework flows in two directions. Design choices at the model and data layer influence system behavior and, ultimately, organizational outcomes. At the same time, expectations at the ecosystem and governance layer—such as regulatory requirements or internal risk policies—flow downward, constraining and shaping system design and model choices. This bidirectional view is consistent with ecosystem-oriented governance models that emphasize the co-evolution of technical systems and institutional arrangements [9,10]. Table 3 summarizes the three layers, their main governance focus, and typical artifacts.

Table 3.

Overview of the three-layered governance framework for LLM-powered enterprise analytics.

The first layer asks what the LLM is doing, on which data, and how its behavior is assessed. At this layer, governance focuses on visibility and control over model behavior before it enters complex enterprise pipelines. A central aspect is the provenance and characteristics of training and adaptation data. Risk mappings for language models show how inadequacies and biases in training data can manifest as discriminatory outputs, misinformation, or other harms [3]. For enterprise analytics, the question becomes whether the data used to train or fine-tune the LLM are appropriately representative of the domain where it will be applied, and whether known gaps are documented and mitigated.

Evaluation data and metrics are equally important. Surveys of bias and fairness highlight the need for task-specific evaluation sets and metrics that go beyond aggregate accuracy [4]. In analytics settings, these can include error profiles for different customer segments, robustness to distribution shifts, and stability of generated narratives under minor input perturbations. Prompt templates and guardrails further shape model behavior; although they are often treated as implementation details, they can encode organizational norms or anti-patterns and therefore warrant documentation and review. As summarized in Table 3, artifacts at this layer include model documentation, data-provenance records, evaluation reports, prompt libraries, and risk registers focused on model behavior.

From a governance perspective, the model and data alignment layer provides the foundation on which subsequent layers build. Without sufficient visibility at this level, higher-level controls may amount to little more than monitoring the symptoms of misalignment rather than its causes.

The second layer shifts the focus from the model in isolation to the systems and workflows into which it is embedded. Here, the central question is how the LLM interacts with users, data sources, and downstream processes. System architecture determines which data the LLM can access, how it is called, and how its outputs are combined with other components. For example, an LLM that has direct read access to a production data warehouse creates different risks than one that operates on curated, de-identified views. Work on algorithmic auditing emphasizes that many failures emerge not from the model alone but from the broader socio-technical system in which it operates [7]. In analytics contexts, this system includes data-integration pipelines, BI tools, and orchestration layers.

User interaction patterns and human-in-the-loop design are also critical. LLMs that generate narratives for analysts to review play a different role than those that directly surface recommendations to executives or customers. Governance models stress the importance of embedding review and override mechanisms into system design rather than treating them as ad hoc practices [6]. Monitoring and logging the complete picture, logs of prompts, outputs, and downstream actions, enable organizations to detect unusual usage patterns, investigate incidents, and support internal or external audits. Table 3 highlights how artifacts such as architecture diagrams, access-control configurations, monitoring dashboards, and incident runbooks capture key decisions at this layer.

The third layer situates LLM-powered analytics within the broader organizational and ecosystem context. It asks how analytics practices align with organizational values, strategies, and external expectations. Roles and responsibilities are a first consideration. Organizational governance frameworks argue that effective AI oversight requires clearly assigned responsibilities across the system life cycle, including design, deployment, monitoring, and decommissioning [6,7]. In practice, this may involve the head of analytics, data platform owners, risk managers, compliance officers, and internal auditors. Policies and standards are a second consideration. Many organizations already have policies governing data use, model risk management, and IT change control; LLM-powered analytics may require updating these policies or clarifying how they apply to generative models.

External alignment adds another layer of complexity. Ecosystem perspectives emphasize that organizations operate within webs of partners, customers, regulators, vendors, and affected communities [9,10]. For LLM-powered analytics, this can include model providers, cloud platforms, regulators issuing AI-related guidance, and customers whose data or experiences are affected. Governance at this layer involves mapping analytics initiatives to regulatory classifications, managing third-party risk, and articulating how organizational values and intended societal impacts, such as fairness or transparency, are reflected in analytics design. As shown in Table 3, artifacts at this layer include governance charters, policy documents, risk taxonomies, committee minutes, and external compliance reports. Having defined the three-layer framework and its bidirectional information flow, we next operationalize each layer into measurable indicators and auditable artifacts (Section 3.2) and then illustrate its application using structured enterprise scenarios (Section 3.3).

3.2. From Models to Metrics: Operational Indicators and Governance Artifacts (Toolkit)

The three-layer framework introduced in Section 3.1 is intentionally abstract: it identifies where governance responsibilities sit in LLM-powered analytics systems and how influence flows across model behavior, system design, and organizational oversight. However, governance only becomes actionable in enterprise settings when these layers are translated into measurable signals and repeatable artifacts that teams can produce, review, and audit over time. Section 3.2 performs this translation.

Rather than proposing new principles, this toolkit specifies how the framework’s layers materialize in the everyday objects that analytics organizations already manage—evaluation reports, dashboards, logs, runbooks, approval records, and committee minutes. The indicators and artifacts described below are not intended as universal benchmarks. Their value lies in creating disciplined evidence pathways: making explicit what must be demonstrated, documented, and reviewed before LLM-enabled analytics can move from experimentation to routine use.

3.2.1. Model and Data Alignment (Layer 1): Operationalizing Model Behavior

At the model and data alignment layer, governance asks a deceptively simple question: what does the LLM actually do on the analytics tasks we care about, and under what conditions does it fail? Operationalization at this layer, therefore, focuses on making model behavior visible and contestable before it is embedded in downstream systems.

In practice, this requires moving beyond generic accuracy claims toward indicators that reflect analytic risk. Common examples include narrative faithfulness (the proportion of generated claims directly supported by input data or retrieved evidence), segment stability (whether performance materially degrades across business units, regions, or subpopulations), and robustness to minor input variation (whether small perturbations produce inconsistent narratives). These indicators directly reflect failure modes reported in enterprise use, where superficially fluent outputs can obscure gaps, bias, or overgeneralization. Known failure patterns are documented explicitly in a model-level risk register, which serves as a living record rather than a one-time assessment.

The corresponding artifacts, evaluation packs, prompt libraries, data-provenance notes, and model risk registers constitute the primary evidence that a model’s behavior has been examined in the context in which it will be used. As summarized in Table 4, these artifacts anchor governance at the point where analytic meaning is first produced.

Table 4.

Example “models-to-metrics” indicators and artifacts mapped to the three layers.

3.2.2. System and Workflow Alignment (Layer 2): Operationalizing Use, Oversight, and Escalation

Many governance breakdowns in enterprise analytics do not originate in the model itself, but in how it is embedded into workflows. The system and workflow alignment layer, therefore operationalizes governance by measuring how outputs are generated, reviewed, acted upon, and corrected.

Here, operational indicators shift from model performance to interaction patterns. Examples include the human-in-the-loop decision rate for high-impact outputs, edit or override rates that reveal where analysts routinely correct LLM narratives, incident frequency and time-to-escalation, and logging completeness across prompts, retrieved sources, outputs, and user actions. These indicators reflect whether oversight mechanisms are functioning as designed, rather than merely existing on paper.

Artifacts at this layer, system cards, monitoring dashboards, incident runbooks, and change-control logs, capture design choices about access, integration, and accountability. They provide the evidence needed to answer questions such as who can use the system, under what conditions, and how deviations are detected and handled. In this sense, system-level governance transforms abstract principles of “human oversight” into observable workflow behavior.

3.2.3. Ecosystem and Governance Alignment (Layer 3): Operationalizing Ownership and Accountability

At scale, LLM-powered analytics are shaped as much by organizational and external constraints as by technical design. The ecosystem and governance alignment layer operationalizes these constraints by making decision rights, obligations, and dependencies explicit.

Operational indicators at this layer, therefore, focus on coverage and clarity rather than performance. Typical examples include RACI completeness across the analytics lifecycle, adherence to defined review cadences, completeness of policy mappings to internal and external requirements, and clarity around third-party dependencies (what is known—and not known—about vendor models, updates, and audit rights). These indicators surface governance gaps that cannot be detected through model or system metrics alone.

The associated artifacts, governance charters, RACI matrices, policy mappings, committee records, and vendor risk notes constitute the formal evidence that responsibility for LLM-enabled analytics has been assigned, exercised, and reviewed. As shown in Table 4, these artifacts close the governance loop by connecting operational evidence back to organizational decision-making forums.

Taken together, the toolkit does not add a fourth layer to the framework. Instead, it makes the existing layers governable by specifying what evidence must exist at each level for LLM-powered analytics to be responsibly deployed and scaled. The indicators and artifacts in Table 4 illustrate how the framework’s abstract distinctions, model, system, and ecosystem, translate into concrete governance work that analytics teams, risk functions, and auditors can jointly evaluate.

Having operationalized the framework into measurable indicators and repeatable artifacts, we next illustrate how these controls and decision gates appear in realistic enterprise analytics settings.

3.3. Illustrative Enterprise Scenarios

Each illustrative enterprise scenario is structured using a common analytical template: (i) the analytical objective and decision context; (ii) the LLM interaction pattern (e.g., summarization, classification, retrieval-augmented generation, agent/tool use); (iii) data sources and sensitivity; (iv) regulatory or assurance context; (v) tier-specific controls and artifacts; and (vi) measurable acceptance criteria used to determine readiness for limited production versus scale. This structure reflects the logic of analytic generalization by clarifying the conditions under which the framework’s control placement, artifacts, and evidence pathways are expected to hold, while preserving confidentiality through anonymization [17].

Rather than serving as empirical case studies, the scenarios are presented as structured application traces. They synthesize recurring patterns observed in practitioner accounts and expert consultations, and are intended to demonstrate how the three-layer framework directs attention to different sources of risk and control at different points in the analytics value chain. In doing so, they show how governance for LLM-powered analytics becomes auditable through measurable criteria and repeatable artifacts, without requiring disclosure of sensitive organizational details.

3.3.1. Regulated Life Sciences Analytics (LLM-Enabled “Trial Health” Agent)

A global life sciences organization deploys an LLM-enabled “trial health” agent to support analytics for late-stage clinical studies. Outputs are used to summarize operational signals—such as recruitment progress, protocol deviations, and data-query backlogs—and may influence management decisions, including site support allocation. As a result, the deployment must align with stringent quality, compliance, and documentation expectations.

At the model layer, governance focuses on whether the agent’s narratives faithfully reflect complex operational data without masking localized risks across regions, sites, or patient subgroups. Evaluation datasets and scoring procedures are constructed around realistic multi-country variation, and prompts are calibrated to clinical vocabularies and controlled terminologies. Evidence at this layer is captured through an evaluation pack and a model-level risk register that documents known failure modes, residual risks, and mitigation strategies.

At the system layer, the agent is embedded within a validated analytics environment. It operates exclusively on curated, access-controlled views of clinical operations data and presents narratives alongside established dashboards rather than as standalone outputs. Human review is mandatory prior to use in decision-making, and the system records whether narratives are accepted, edited, or rejected. These interaction logs support ongoing monitoring and periodic audit. Integration choices, permissions, retrieval behavior, and updates are documented through a system card and managed via formal change-control records.

At the organizational layer, the deployment is situated within the sponsor’s quality and compliance framework. Accountability is explicitly assigned across clinical operations, biostatistics, and quality assurance. Documentation clarifies that the agent provides decision support rather than serving as an authoritative source of record. Governance forums periodically review outputs, exceptions, and incident logs against internal standard operating procedures and relevant assurance expectations. The decision to scale beyond limited production depends on meeting predefined faithfulness and privacy thresholds, supported by auditable evidence (Table S1).

3.3.2. Financial Institution Analytics (LLM-Based Assistant for Risk Analysts)

A financial institution pilots an LLM-based assistant to support risk analysts who interpret internal policies and externally defined regulatory requirements under strict accountability and model risk management expectations.

At the model layer, prompts, retrieval pipelines, and evaluation sets are designed to test whether the assistant consistently handles regulatory definitions, thresholds, and jurisdictional differences. Systematic failure cases, such as hallucinated regulations or incorrect threshold logic, are explicitly logged in a model-level risk register and used to refine acceptance criteria [2,5]. Where outputs could differentially affect customer segments or decision outcomes, disparity checks are incorporated into the evaluation process.

At the system layer, the assistant operates in a sandboxed environment. It can query approved internal repositories and draft analytical rationales, but it cannot write to production systems or directly trigger downstream actions. Analysts must explicitly accept, edit, or reject outputs, and all interactions are logged as part of the audit trail. Runbooks define permitted use cases, mandatory human review conditions, and escalation paths when confidence is low or policy interpretations appear ambiguous.

At the governance layer, the pilot is mapped to the institution’s existing model risk management and oversight processes. Ownership, usage constraints, independent review expectations, and criteria for progression from pilot to production are clearly specified (Table S1). Go/no-go decisions depend on meeting bias and disparity tolerances, security testing outcomes (e.g., resistance to prompt injection), and demonstrable readiness of monitoring and incident-response mechanisms.

Across both scenarios, the framework functions not as a checklist but as a disciplining lens. It guides where controls should be placed, at the level of model behavior, system integration, or organizational oversight, and links each placement to concrete, auditable evidence such as evaluation reports, interaction logs, governance approvals, and incident runbooks. The scenarios illustrate how “models-to-metrics” governance can be instantiated in enterprise analytics settings, enabling organizations to reason systematically about readiness, risk, and scale without relying on opaque assurances or ad hoc judgment.

4. Discussion

The proposed framework extends existing work on AI governance and auditing by anchoring it explicitly in enterprise analytics practice. Like the Hourglass Model, it recognizes that high-level ethical principles must be translated into concrete organizational processes and system-level requirements [6]. Like ecosystem-oriented perspectives, it highlights the mutual shaping of technical and institutional structures [9]. Like end-to-end algorithmic auditing proposals, it emphasizes documentation, traceability, and lifecycle accountability [7]. What distinguishes this framework is its focus on the everyday structures through which analytics teams deliver value, models, systems, and metrics, and its explicit orientation toward LLM-powered workflows. To make this positioning explicit for enterprise analytics readers, Table 5 compares the framework with closely related governance and auditing models across unit of analysis, strengths, limitations, and typical artifacts.

Table 5.

Novelty and contribution relative to prior models.

The core contribution of this work lies in addressing a persistent gap between AI governance frameworks and the realities of enterprise analytics practice. While existing approaches provide valuable principles and audit structures, they often leave analytics teams with limited guidance on where governance controls should be applied, what evidence should be produced, and how routine analytical work connects to organizational oversight. As a result, governance frequently remains detached from the workflows through which LLM-enabled analytics influence decisions. This framework addresses that gap by anchoring governance directly in the analytics value chain—locating controls at the points where risk is created and amplified: model behavior, workflow integration, and organizational decision rights. By making governance explicitly bidirectional, it shows how ecosystem-level requirements shape system and model design, while operational evidence generated within analytics workflows feeds back into governance and assurance cycles [9,10]. The accompanying “models-to-metrics” toolkit (Section 3.2) specifies auditable indicators and repeatable artifacts at each layer, enabling governance to function as a continuous practice embedded in analytics operations rather than as a periodic, retrospective exercise [6,7,8].

For analytics leaders, the framework implies a shift in how governance work is approached. At the model and data layer, governance centers on evaluation design, documentation, and prompt management rather than one-time model selection. At the system and workflow layer, it becomes a matter of architecture and user experience: how outputs are surfaced, reviewed, corrected, and escalated. At the ecosystem and governance layer, it foregrounds organizational design questions around accountability, policy alignment, and incentives, shaping how LLM-enabled analytics are authorized, monitored, and revised over time.

The framework has limitations. It does not resolve normative debates about what constitutes “responsible” or “aligned” use of LLMs, nor does it claim exhaustive coverage of all possible risks. Its contribution lies in structuring governance work—clarifying control placement, evidence expectations, and escalation pathways—rather than prescribing universal answers. While informed by literature and expert consultations, the framework has not yet been systematically evaluated across multiple organizations. Future work could examine its performance in real deployments, its interaction with emerging regulations, and its adaptation to smaller organizations or cross-organizational analytics ecosystems.

The framework is most applicable in contexts where analytics outputs influence consequential decisions (e.g., financial, clinical, or operational), where LLMs are embedded into workflows rather than used solely for drafting, and where auditability is required, such as regulated environments or settings with formal internal assurance. For smaller organizations, the same logic applies but can be instantiated as minimum viable governance: a lightweight evaluation pack, a prompt library, basic logging and monitoring, a clearly named accountable owner, and an explicit escalation path. As organizations scale their use of LLM-enabled analytics, ecosystem-level controls—such as RACI completeness, clarity around vendor dependencies, procurement and audit rights, and defined review cadences—become increasingly important [9,10].

5. Conclusions

LLMs have moved from experimental tools to central components of enterprise analytics. The question facing organizations is no longer whether they will use LLMs, but how they will govern them so that their outputs remain aligned with organizational goals, values, and obligations. This paper has proposed a three-layered governance framework—model and data alignment, system and workflow alignment, and ecosystem and governance alignment—that connects models to metrics and governance mechanisms in a way that mirrors how analytics teams already work.

By integrating insights from foundation-model research, alignment theory, AI governance, and algorithmic auditing [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], the framework offers a structured way to think about LLM-powered analytics that is both theoretically grounded and oriented toward practice. Its primary contribution is to reframe responsible AI not as an external constraint but as an intrinsic part of designing and operating analytics systems. As enterprises refine their use of LLMs, this framework can serve as a starting point for deeper empirical studies and for practical conversations among analytics, IT, risk, and compliance teams.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/analytics5010008/s1, Table S1: Scenario parameterization and evidence used to support the framework; all other relevant conceptual development and examples are contained in the main text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, [D.D.]; methodology, [D.D. and A.D.]; investigation, [D.D. and A.D.]; writing—original draft preparation, [D.D.]; writing—review and editing, [A.D.]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative expert consultation notes generated and analyzed in this study contain confidential professional information and are not publicly available. No additional datasets were created or used beyond those described in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the practitioners and colleagues who shared perspectives on enterprise analytics and AI governance, which helped shape the framework presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of literature; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BI | Business Intelligence |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MLOps | Machine Learning Operations |

References

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’21); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, L.; Mellor, J.; Rauh, M.; Griffin, C.; Uesato, J.; Huang, P.; Cheng, M.; Glaese, M.; Balle, B.; Kasirzadeh, A.; et al. Ethical and Social Risks of Harm from Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.04359. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.04359 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, I. Artificial Intelligence, Values, and Alignment. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymäki, M.; Minkkinen, M.; Birkstedt, T.; Viljanen, M. Putting AI Ethics into Practice: The Hourglass Model of Organizational AI Governance. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.00335. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.00335 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Smith-Loud, J.; Theron, D.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI Accountability Gap: Defining an End-to-End Framework for Internal Algorithmic Auditing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’20); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mökander, J.; Schuett, J.; Kirk, H.R.; Floridi, L. Auditing Large Language Models: A Three-Layered Approach. AI Ethics 2024, 4, 1085–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C. Artificial Intelligence for a Better Future: An Ecosystem Perspective on the Ethics of AI and Emerging Digital Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, H.; David, P.; Seberger, J.S. A Multilevel Framework for AI Governance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03198. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.03198 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sculley, D.; Holt, G.; Golovin, D.; Davydov, E.; Phillips, T.; Ebner, D.; Chaudhary, V.; Young, M.; Crespo, J.-F.; Dennison, D. Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar]

- NIST AI 100-1; Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0). National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Boulder, CO, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing Conceptual Articles: Four Approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S. The Nature of Theory in Information Systems. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 611–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.