Abstract

Clinical reasoning (CR) is the construct by which healthcare professionals assemble and interpret clinical information to formulate a diagnosis and management plan. Developing this skill can aid with medical decision-making and reduce clinical errors. Increasingly, CR is being included in undergraduate medical curricula, but the cultivation of this skill must continue in postgraduate training as doctors evolve to manage patients with increasing complexity. This is especially relevant in postgraduate training as doctors rotate through multiple specialties, assessing undifferentiated patients. Clinical trainers should therefore not only help develop their trainees’ CR skills, but also effectively evaluate their progression in this competency through placement-based assessment tools. This article introduces the reader to CR theories and principles before exploring four such methods for evaluating a trainee’s CR skills in a workplace setting. The various workplace tools described in this article are not intended to be prescriptive methodologies that must be rigidly followed, but instead offer a range of approaches that supervisors can dip into, and even combine, as suited to their trainees’ needs and level of performance to help foster this crucial aspect of professional development.

1. Introduction

Clinical reasoning (CR) is the process by which healthcare professionals gather, assemble, and interpret clinical information to formulate differential diagnoses and onward investigative and management plans [1]. It is a skill that can be taught, refined, and evaluated and has been shown to positively impact patient safety with improved decision-making and reduced clinical errors [2]. In recent years, the medical education literature has witnessed a surge in both the empirical and non-empirical exploration of this field, with the agreement that CR skill development should commence during undergraduate study and be specifically further developed throughout postgraduate training [3]. Competence in CR must be built upon strong foundations of clinical knowledge; forming differential diagnoses and selecting relevant information is established from an understanding of pathophysiology, pharmacology, and illness scripts developed from clinical encounters over the years [4]. Therefore, there is an onus on postgraduate supervisors to not only explicitly facilitate their trainees’ development of CR skills but also to evaluate how well their trainees apply these skills in their everyday clinical encounters.

One of the most established and widely accepted models that explains how clinicians reason through clinical problems is the dual-process theory [5]. This model proposes two systems of thinking when clinical decision-making is taking place. System 1 thinking is based on pattern recognition and intuition to solve a clinical problem quickly. For example, a trainee who reviews a patient with a unilateral red, hot, swollen calf following a long-haul flight will likely rapidly recognise this represents a possible deep vein thrombosis by effortlessly matching the patient’s stereotypical symptoms with learnt patterns of how this condition presents. System 2 thinking, on the other hand, is a more analytical, rational process where multiple pieces of information are collated and compared in the context of the patient’s circumstances [6]. It is cognitively more time-consuming, requiring a deliberate and systematic thought process. In the context of differential diagnosis making, System 2 thinking utilises a hypothetico--deductive reasoning approach through purposeful history-taking and hypothesis-driven physical examination [7]. Purposeful history-taking moves the clinical learner away from simply working through a series of standardised questions that are asked in an ‘interview’ approach for all patients, which, whilst being aligned to established consultation frameworks such as Calgary–Cambridge, is devoid of deliberate cognitive clinical problem-solving [2]. Instead, the clinician systematically collects data from the patient’s medical history through a deliberate and logical approach. This process involves initially generating a list of possible differential diagnoses and then using the patient’s responses to incrementally adjust the likelihood of each. Through this iterative process, the clinician methodically narrows down and refines the list of probable diagnoses as the consultation advances. In doing so, the clinician is required to discriminate between relevant and less-relevant information and should skilfully adapt their questions to incorporate the patient demographic with epidemiological probabilities, whilst continually utilising data gained from earlier in the process to inform the onward data-gathering process [8]. Hypothesis-driven physical examination subsequently follows and offers a CR-based alternative to the typical system-based examinations traditionally taught in undergraduate medical education [9]. In this approach, the clinician focuses their examination on the differential diagnoses generated by the prior history and encourages them to consider which examination signs are relevant.

The dual-process model suggests that as clinicians become more experienced, they utilise both systems of thinking throughout their clinical practice, toggling between systems unconsciously, across, and even within the same clinical encounters [6]. However, less-experienced clinicians such as postgraduate trainees are at risk of overly relying on system 1 thinking, given its speed and ease. This has recognised adverse patient safety implications given that they do not yet have sufficient depth and range of clinical experience to accurately pattern-recognise in practice [10]. There is therefore a recognised need to focus more on developing system 2 thinking in medical students and postgraduate clinical trainees to minimise clinical errors. Being aware of one’s thinking processes and learning processes is termed “metacognition” and helps clinicians become more consciously aware of which system of thinking they are working within, or indeed to shift towards, to achieve safe clinical outcomes [6]. Lastly, the concept of cognitive biases within reasoning frameworks has been highlighted in relation to potentially reducing clinical error. These are cognitive “shortcuts” that are applied subconsciously to aid with cognitive load and decision-making. Biases interject with system 1 thinking but may be overcome through metacognitive strategies and a readiness to engage with system 2 thinking to reduce diagnostic errors [4], though the evidence for this for such approaches is questioned [11].

2. Workplace-Based Clinical Reasoning Evaluation Tools

There are several documented methods for evaluating CR skills within the everyday clinical setting. We describe four such methods and discuss how these can be used in practice. It is important to consider the variability in trainees’ skills and metacognitive abilities. Therefore, we recommend testing each tool to determine which one best supports both the trainee and supervisor, and in which clinical contexts they are most effective.

3. One Minute Preceptor (OMP)

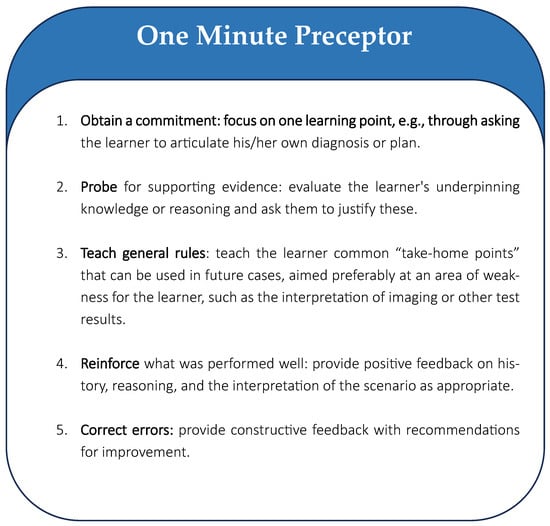

This model, sometimes referred to as the five microskills, was initially designed for use with primary care practitioners but quickly became established globally as a simple way to have a time-limited focused exploration of a learner’s thinking following a case presentation [12]. It uses five criteria to frame discussions with an emphasis on the learner’s demonstration of CR skills and underpinning knowledge, with the opportunity throughout to provide targeted feedback, as summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The one minute preceptor tool.

Like the other tools discussed in this paper, the OMP focuses on encouraging reflective practice to help the trainee understand their decision-making process, rather than the trainer purely imparting factual knowledge for the discussion. This tool helps guide a CR-focused debrief following a patient encounter and is well suited to junior trainees as the supervisor can guide the discussion in a structured manner, therefore providing a safe space for reflection and the opportunity for constructive feedback to the trainee [12]. It has the advantage of being quick to use; however, the lack of depth may not be adequate for all trainees or allow for sufficient exploration of complex cases.

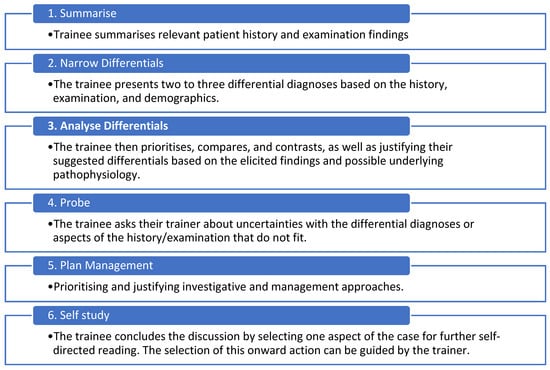

The SNAPPS model is an acronym-based model, as described in Figure 2 [13].

Figure 2.

The elements of the SNAPPS assessment.

Like the OMP, SNAPPS allows for an efficient CR-focused discussion following a patient encounter when time is limited. However, it is learner-led rather than supervisor-led. As such, it requires the learner to be experienced enough to know how best the tool can be utilised to allow for a meaningful discussion that encourages them to reflect upon their own metacognition. A randomised controlled trial comparing the OMP with SNAPPS in final-year medical students found no significant difference in the expression of CR skills in the assessed domains; however, participants in the SNAPPS group were more proactive in asking questions and more likely to justify the probable diagnoses [14].

4. Clinical Reasoning Task Checklist

Goldszmitz et al. developed the Clinical Reasoning Task Checklist [15], which has 24 reasoning tasks the trainee should demonstrate or articulate during a patient encounter (see Table 1). This tool can be used both whilst observing the trainee undertake a consultation or during case presentations.

Table 1.

The Clinical Reasoning Task Checklist (modified from Appendix 1; Goldsmitz et al. [15]).

This checklist offers a prescriptive approach to assessing CR; consequently, it is more time-consuming to use than the OMP and SNAPPS. Due to the checklist-based criteria, we suggest it may be more appropriate for early-stage trainees who may struggle to articulate their reasoning and thus benefit from a more granular prompt-based tool. Additionally, the CR checklist could serve as a useful aide-memoire by the trainee to guide their patient assessments and case presentations.

5. The Assessment of Reasoning Tool (ART)

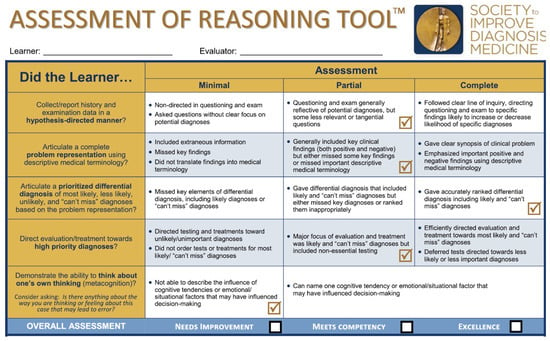

This final tool was developed by Thammasitboon et al. [16] to assess a verbalised case presentation following a patient assessment and is shown, with the authors’ permission, in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The Assessment of Reasoning Tool [16]. Used with permission from the authors.

With fewer criteria to assess than the CR Task Checklist, the ART may be less time-consuming to use in practice. The positive and negative indicators for each domain help guide not just the evaluative rating but can inform subsequent debriefing and feedback. As the ART contains clear, concise indicators and emphasises metacognition, this tool is likely to be suitable for assessing trainees of all stages, with resultant feedback guiding the improvement of CR skills and reinforcing good practice. However, it does require sufficient time to be used; therefore, appropriate case selection is important.

6. Conclusions

CR is an important skill that can be taught, developed, and evaluated throughout clinical training. We encourage clinical supervisors to familiarise themselves with the concepts of CR so they can explicitly focus on this in feedback discussions with their trainees. The various workplace tools described in this article, and summarised in Table 2, are not intended to be prescriptive methodologies that must be rigidly followed; instead, they offer a range of approaches that trainers can dip into, and even combine, as suited to their trainees’ needs and level of performance to help foster this crucial aspect of professional development.

Table 2.

Comparison of CR evaluative tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.N. and H.K.T. Original draft preparation, A.M.N. Writing—review and editing, A.M.N. and H.K.T. Supervision H.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Daly, P. A concise guide to clinical reasoning. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, N.; Bartlett, M.; Gay, S.; Hammond, A.; Lillicrap, M.; Matthan, J.; Singh, M. Consensus statement on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, G.K.-H.; Chan, P.-C. Clinical Reasoning in Medical Education: A Primer for Medical Students. Teach. Learn. Med. 2023, 36, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.S. In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croskerry, P. Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: Applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2009, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaccia, T.; Tardif, J.; Triby, E.; Charlin, B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: The dual-process theory. Med. Educ. Online 2011, 16, 5890. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3060310/ (accessed on 1 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, A.; Rencic, J.; Cosby, K.; Rusz, D.; Papa, F.; Croskerry, P.; Zierler, B.; Harkless, G.; Giuliano, M.A.; Schoenbaum, S.; et al. Competencies for improving diagnosis: An interprofessional framework for education and training in health care. Diagnosis 2019, 6, 335–341. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/dx-2018-0107/html (accessed on 1 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruczynski, L.I.; van de Pol, M.H.; Schouwenberg, B.J.; Laan, R.F.; Fluit, C.R. Learning clinical reasoning in the workplace: A student perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yudkowsky, R.; Otaki, J.; Lowenstein, T.; Riddle, J.; Nishigori, H.; Bordage, G. A hypothesis-driven physical examination learning and assessment procedure for medical students: Initial validity evidence. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Schiff, G.D.; Graber, M.L.; Onakpoya, I.; Thompson, M.J. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, G.R.; Eva, K.W. Diagnostic error and clinical reasoning. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neher, J.O.; Gordon, K.C.; Meyer, B.; Stevens, N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J. Am. Board. Fam. Pract. 1992, 5, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolpaw, T.M.; Wolpaw, D.R.; Papp, K.K. SNAPPS: A Learner-centered Model for Outpatient Education. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, E.D.T.; Ibiapina, C.C.; Alvim, C.G.; Fernandes, R.A.F.; Carvalho-Filho, M.A.; Brand, P.L.P. Case presentation methods: A randomized controlled trial of the one-minute preceptor versus SNAPPS in a controlled setting. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2020, 9, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldszmidt, M.; Minda, J.P.; Bordage, G. Developing a Unified List of Physicians’ Reasoning Tasks During Clinical Encounters. Acad Med. 2013, 88, 390–394. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/00001888-201303000-00030 (accessed on 1 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammasitboon, S.; Rencic, J.J.; Trowbridge, R.L.; Olson, A.P.; Sur, M.; Dhaliwal, G. The Assessment of Reasoning Tool (ART): Structuring the conversation between teachers and learners. Diagnosis 2018, 5, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).