Faculty and Student Perspectives on Launching a Post-Pandemic Medical School: A Philippine Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

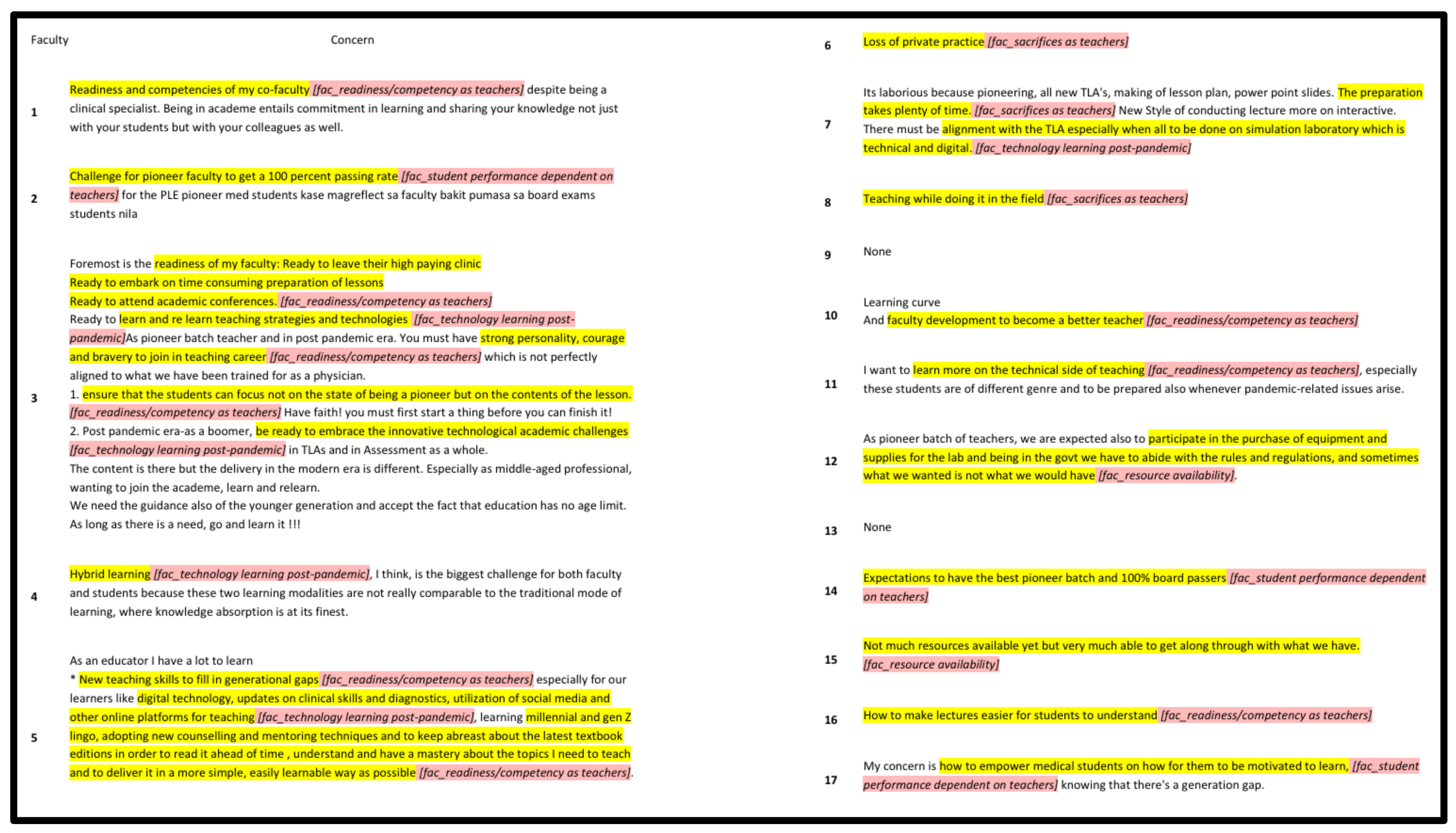

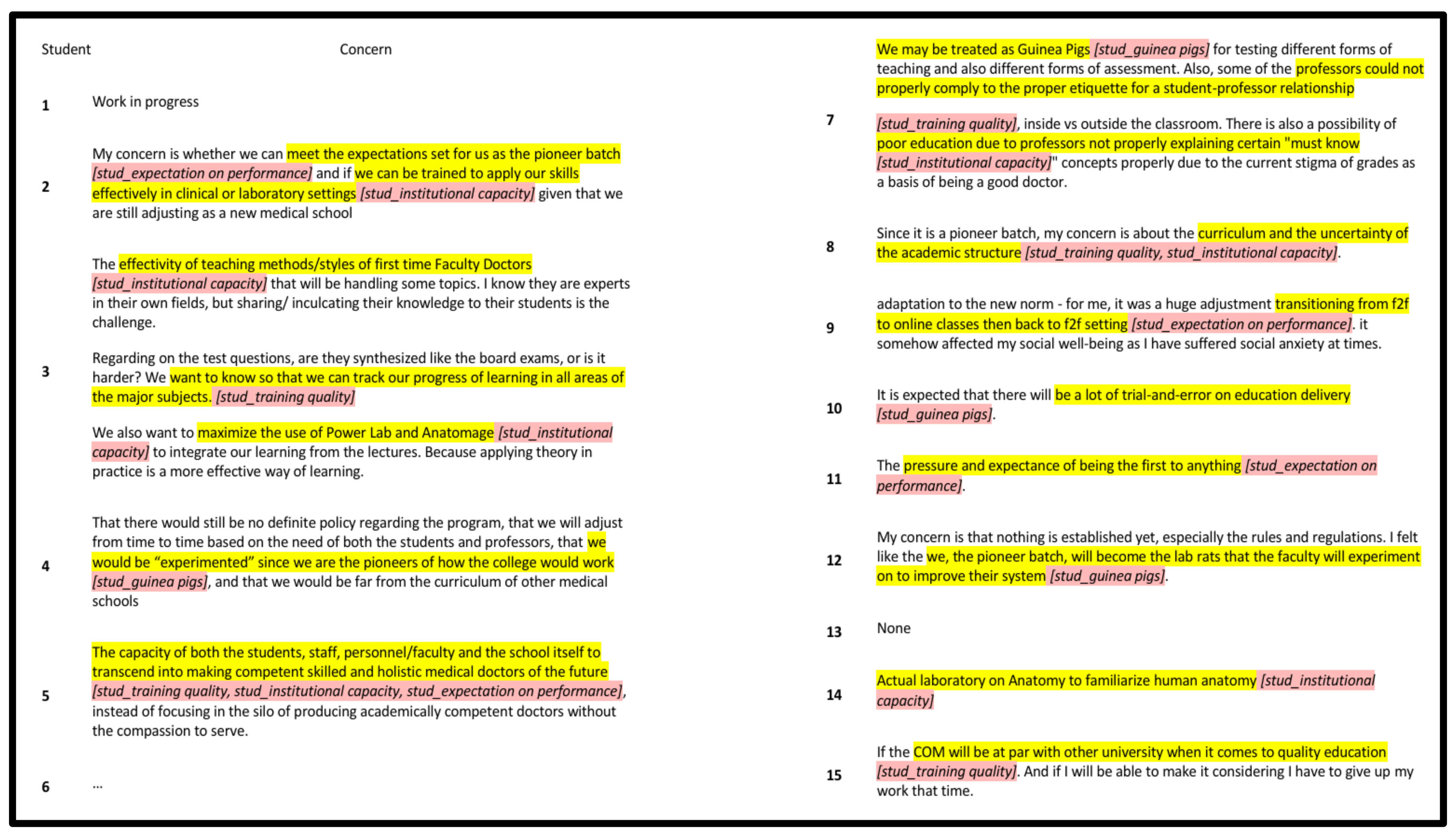

3. Results

“Foremost is the readiness of my faculty: ready to leave their high paying clinic, ready to embark on time consuming preparation of lessons, ready to attend academic conferences, ready to learn and re learn teaching strategies and technologies.”

“Challenge for pioneer faculty to get a 100 percent passing rate for the PLE pioneer med students.”

“Hybrid learning, I think, is the biggest challenge for both faculty and students because these two learning modalities are not really comparable to the traditional mode of learning, where knowledge absorption is at its finest.”

“Not much resources available yet but very much able to get along through with what we have.”

“The effectivity of teaching methods/styles of first time Faculty Doctors that will be handling some topics. I know they are experts in their own fields, but sharing/inculcating their knowledge to their students is the challenge.”

“My concern is that nothing is established yet, especially the rules and regulations. I felt like the we, the pioneer batch, will become the lab rats that the faculty will experiment on to improve their system.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Faculty and Student Motivations and Concerns

4.2. Medical Education Landscape Across Different Pandemic Eras

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babbar, M.; Gupta, T. Response of educational institutions to COVID-19 pandemic: An inter-country comparison. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 20, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, Z.; Javed, A.; Azeem, M.W. The effects of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 38, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Almusharraf, N.; Aldeghaither, D. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in higher education: Evidence from G20 countries. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 9 (Suppl. S1), 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; Pérez-Moreno, M.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althwanay, A.; Ahsan, F.; Oliveri, F.; Goud, H.K.; Mehkari, Z.; Mohammed, L.; Javed, M.; Rutkofsky, I.H. Medical Education, Pre- and Post-Pandemic Era: A Review Article. Cureus 2020, 12, e10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Bashir, S.; Rana, K.; Lambert, P.; Vernallis, A. Post-COVID-19 Adaptations; the Shifts Towards Online Learning, Hybrid Course Delivery and the Implications for Biosciences Courses in the Higher Education Setting. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 711619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Steele, K.; Singh, L. Combining the Best of Online and Face-to-Face Learning: Hybrid and Blended Learning Approach for COVID-19, Post Vaccine, & Post-Pandemic World. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2021, 50, 140–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardanova, Z.; Belaia, O.; Zuevskaya, S.; Turkadze, K.; Strielkowski, W. Lessons for Medical and Health Education Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Marino, P.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Fortifying the Foundations: A Comprehensive Approach to Enhancing Mental Health Support in Educational Policies Amidst Crises. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaraskera, D. Emerging stronger post pandemic: Medical and Health Professional Education. Asia Pac. Sch. 2023, 8, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybowski, C.; Harendza, S. Validation of the Physician Teaching Motivation Questionnaire (PTMQ). BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, M.-Á.; López-Roig, S.; Sánchez, S.; Hart, J.; Johnston, M.; Dixon, D. Analysing motivation to do medicine cross-culturally: The International motivation to do medicine scale. Escr. Psicol.—Psychol. Writ. 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.W. Intrinsic Motivation at Work: Building Energy and Commitment; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, R. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefy, A.; Ghassemi, G.; Firouznia, S. Motivation and academic achievement in medical students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2012, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Angeli, F.; Dhirar, N.; Singla, N.; Ruwaard, D. What motivates medical students to select medical studies: A systematic literature review. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genn, J.M. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 23: Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—A unifying perspective. Med. Teach. 2001, 23, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, R.M.; Laidlaw, J.M. Essential Skills for a Medical Teacher: An Introduction to Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Croiset, G.; Mann, K.V.; Custers, E.; Ten Cate, O. Have motivation theories guided the development and reform of medical education curricula? A review of the literature. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 2131–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeilia, A.; Sotiropoulos, M.G.; Hanrahan, J.G.; Janga, D.; Dedeilias, P.; Sideris, M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: A systematic review. In Vivo 2020, 34 (Suppl. S3), 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Legorburu Fernnadez, I.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Burnout among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, A.J.; Lee, C.; Jones, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Davis, J.A.; Boysen-Osborn, M.; Kashima, K.J.; Krane, N.K.; Rae, G.; Kman, N.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garba, S.A.; Abdulhamid, L. Students’ Instructional Delivery Approach Preference for Sustainable Learning Amidst the Emergence of Hybrid Teaching Post-Pandemic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.; Wardat, S.; Akour, M. The Need of Integrating Digital Education in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M.; Mirzazadeh, A.; Azarpira, A. A Survey of Medical Students’ Perceptions of the Quality of their Medical Education upon Graduation. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2008, 37, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 1997, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysart, S.; Weckerle, C. Professional Development in Higher Education: A Model for Meaningful Technology Integration. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2015, 14, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.N.; Condes Moreno, E.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yañez-Sepulveda, R.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Navigating the New Normal: Adapting Online and Distance Learning in the Post-Pandemic Era. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Overall |

|---|---|

| Faculty (n = 17) | |

| Age (years) | 50.4 ± 5.5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5 (30%) |

| Female | 12 (70%) |

| Position | |

| Associate Professor | 12 (70%) |

| Professor | 5 (30%) |

| Specialty | |

| Family and Community Medicine | 3 (17.6%) |

| Internal Medicine | 3 (17.6%) |

| Obstetrics–Gynecology | 2 (11.8%) |

| Pathology | 3 (17.6%) |

| Pediatrics | 3 (17.6%) |

| Radiology | 1 (6%) |

| Surgery | 2 (11.8%) |

| Years in Teaching | 5.5 ± 4.6 |

| Student (n = 15) | |

| Age (years) | 25.3 ± 2.7 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 (40%) |

| Female | 9 (60%) |

| Undergraduate Degree | |

| Biology | 4 (26.67%) |

| Chemistry | 1 (6.67%) |

| Food Science | 1 (6.67%) |

| Laboratory Science | 6 (40%) |

| Pharmacy | 3 (20%) |

| Question | Mean Score |

|---|---|

| Faculty | |

| Intrinsic Motivation | |

| 1. I look forward to my next teaching unit most of the time. | 4.53 ± 0.5 |

| 2. I enjoy my teaching most of the time. | 4.65 ± 0.6 |

| 3. During teaching, I am completely in my element. | 4.59 ± 0.5 |

| 4. Teaching enriches my job. | 4.65 ± 0.5 |

| 5. I teach because it’s important for me to make my contribution to students becoming good physicians in the future. | 4.88 ± 0.5 |

| 6. I teach because I am convinced it’s a physician’s duty to pass on his knowledge. | 4.65 ± 0.3 |

| 7. I teach because I find my lessons’ contents important. | 4.65 ± 0.5 |

| Extrinsic Motivation | |

| 8. I teach because otherwise I would have a bad conscience towards my colleagues. | 2.71 ± 0.5 |

| 9. I teach because otherwise I would have a bad conscience towards my supervisors. | 2.65 ± 1.2 |

| 10. I teach because I need the lessons to accomplish my occupational objectives. | 2.71 ± 1.2 |

| 11. I teach because it is advantageous to my occupation. | 3.53 ± 1.2 |

| 12. I teach because it could promote my career. | 3.41 ± 1.2 |

| 13. I teach most of the time because my supervisors expect it from me. | 2.76 ± 1.3 |

| 14. I mainly teach because it belongs to my scope of duties. | 3.35 ± 1.4 |

| 15. I mainly teach because otherwise I would get into trouble with my supervisors. | 2.06 ± 1.3 |

| Amotivation | |

| 16. I teach although teaching is rather irrelevant to me in comparison to my other occupational activities. | 1.59 ± 1.1 |

| 17. I teach although I hardly ever feel like doing it. | 1.59 ± 0.6 |

| 18. I teach although I often perceive it as an annoying chore. | 1.53 ± 0.5 |

| Student | |

| Status/Security | |

| 1. Opportunity for high income | 3.47 ± 1.3 |

| 2. Social prestige/status | 2.93 ± 1.2 |

| 3. Job security | 4.2 ± 1 |

| 4. The education leads to a defined profession | 4.33 ± 0.7 |

| 5. Classroom-like study program | 3.2 ± 1 |

| 6. Opportunity to take advantage of good grades | 2.73 ± 1.2 |

| People | |

| 7. Being a doctor provides opportunity for social and humanitarian effort | 4.47 ± 0.6 |

| 8. Opportunity to work with people | 4.2 ± 0.8 |

| 9. Opportunity to care for people | 4.73 ± 0.6 |

| 10. Interest in relations between health, well-being and society | 4.67 ± 0.6 |

| Research | |

| 11. Desire for challenge | 3.67 ± 1.5 |

| 12. Interest in human biology | 4.13 ± 0.7 |

| 13. Opportunity to perform research | 3 ± 1.3 |

| 14. General interest in natural science | 4.27 ± 1 |

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Statistic | Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty | |||||

| Age | Intrinsic Motivation | Spearman-rho | 0.005022922 | 0.99 | Not significant |

| Age | Extrinsic Motivation | Spearman-rho | 0.333743842 | 0.93 | Not significant |

| Age | Amotivation | Spearman-rho | 0.161465315 | 0.96 | Not significant |

| Sex | Intrinsic Motivation | t-test | −1.107489593 | 0.28 | Not significant |

| Sex | Extrinsic Motivation | t-test | −2.103586478 | 0.05 | Not significant |

| Sex | Amotivation | t-test | −0.945756026 | 0.35 | Not significant |

| Years in Teaching | Intrinsic Motivation | Spearman-rho | −0.23199472 | 0.37 | Not significant |

| Years in Teaching | Extrinsic Motivation | Spearman-rho | −0.05417218 | 0.80 | Not significant |

| Years in Teaching | Amotivation | Spearman-rho | −0.153135813 | 0.48 | Not significant |

| Student | |||||

| Age | Status/Security Motivation | Spearman-rho | −0.042163312 | 0.99 | Not significant |

| Age | People Motivation | Spearman-rho | 0.048711068 | 0.99 | Not significant |

| Age | Research Motivation | Spearman-rho | −0.098361308 | 0.98 | Not significant |

| Sex | Status/Security Motivation | t-test | −0.022034772 | 0.98 | Not significant |

| Sex | People Motivation | t-test | −0.978987151 | 0.34 | Not significant |

| Sex | Research Motivation | t-test | −0.93131927 | 0.36 | Not significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balmores, E.J., Jr.; Maylem, G. Faculty and Student Perspectives on Launching a Post-Pandemic Medical School: A Philippine Case Study. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020021

Balmores EJ Jr., Maylem G. Faculty and Student Perspectives on Launching a Post-Pandemic Medical School: A Philippine Case Study. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(2):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020021

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalmores, Eugene John, Jr., and Generaldo Maylem. 2025. "Faculty and Student Perspectives on Launching a Post-Pandemic Medical School: A Philippine Case Study" International Medical Education 4, no. 2: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020021

APA StyleBalmores, E. J., Jr., & Maylem, G. (2025). Faculty and Student Perspectives on Launching a Post-Pandemic Medical School: A Philippine Case Study. International Medical Education, 4(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020021