Abstract

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics have led to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pose a significant threat due to adverse drug reactions, increased healthcare costs, and poor patient outcomes. Antibiotic stewardship programs, including antibiotic de-escalation, aim to optimize antibiotic use and to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to fill the gap by analyzing the current literature on the implications of antibiotic de-escalation in patients on antibiotic use, duration of hospital stay, mortality, and cost; to update clinical practice recommendations for the proper use of antibiotics; and to offer insightful information about the efficacy of antibiotic de-escalation. Based on the PRISMA 2020 recommendations, a comprehensive literature search was conducted using electronic databases and reference lists of identified studies. Eligible studies were published in English, conducted in humans, and evaluated the impact of antibiotic de-escalation on antibiotic consumption, length of hospitalization, mortality, or cost in hospitalized adult patients. Data were extracted using a standardized form, and the quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. The data from 25 studies were pooled and analyzed using the Revman-5 software, and statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using a chi-square test and I2 statistics. Among the total studies, seven studies were conducted in pediatric patients and the remaining studies were conducted in adults. The studies showed a wide range of de-escalation rates, with most studies reporting a rate above 50%. In some studies, de-escalation was associated with a decrease in antimicrobial utilization and mean length of stay, but the impact on overall cost was mixed. Our pooled analysis for mortality reported that a significant difference was observed between the de-escalation group and the non-de-escalation group in a random effect model (RR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.52–0.86, p = 0.001). The results suggest that de-escalation therapy can be applied in different healthcare settings and patient populations. However, the de-escalation rate varied depending on the study population and definition of de-escalation. Despite this variation, the results of this systematic review support the importance of de-escalation as a strategy to optimize antibiotic therapy and to reduce the development of subsequent antibiotic resistance. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of de-escalation on patient outcomes and to standardize the definition of de-escalation to allow for better comparison of studies.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics are essential medications for treating bacterial infections [1], but misuse and overuse of empirical broad spectrum antibiotics have led to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [2,3,4] and pose a significant threat due to adverse drug reactions, increased healthcare costs, and poor patient outcomes [5,6]. To address these issues, several strategies have been proposed, including antibiotic stewardship programs (ASP) that aim to optimize antibiotic use and to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance (ABR) [7]. One ASP approach to minimizing the negative consequences is antibiotic de-escalation, which involves changing from broad-spectrum to narrow-spectrum antibiotics or stopping antibiotics altogether based on clinical and microbiological data [7]. Transitioning from intravenous to oral therapy and shifting from high-shelf to low-shelf antibiotics for standard treatment are also strategies for antibiotic de-escalation [8]. Antibiotic de-escalation is a commonly advised treatment strategy that is recommended by several guidelines for diverse clinical diseases. De-escalation can help to reduce the selection pressure by exposing bacteria to narrower-spectrum antibiotics and avoiding non-pathogenic bacteria that are harmless [9]. In clinical practice, de-escalation strategies hinge upon a profound understanding of microbiological data and antibiotic susceptibility test results. These results serve as the cornerstone and allow healthcare providers to transition from broad-spectrum antibiotics to narrower-spectrum options or to shift from high-reserve antibiotics, typically reserved for challenging cases, to standard treatment antibiotics. Without this critical microbiological information, the application of de-escalation strategies becomes challenging and may even risk therapeutic failure [10,11].

A systematic review has shown that antibiotic de-escalation was associated with a significant reduction in total antibiotic consumption [12]. A retrospective cohort study of patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia found that antibiotic de-escalation was associated with rational antibiotic usage without impacting therapeutic outcomes [13]. Studies have also shown that antibiotic de-escalation was not associated with an increase in length of intensive care units (ICU) stay or mortality [9,12,14]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated a cost reduction linked to antibiotic de-escalation [9,12,15]. Antibiotics with a broader spectrum are often more costly than antibiotics with a narrower scope [16]. Patients are more prone to develop adverse effects such diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting while using broad-spectrum antibiotics. These adverse effects increase the expense and length of patients’ hospital stays [17]. De-escalation can also assist by switching to antibiotics with a narrower range that are less likely to produce these adverse effects. Antibiotic de-escalation can assist patients’ quality of life in addition to the advantages already discussed [12].

Antibiotic de-escalation poses a few possible risks. Firstly, it is possible that a patient’s illness cannot be treated using narrow-spectrum antibiotics [18]. In this situation, it may be necessary to switch the patient back to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Secondly, the risk of infection with resistant bacteria may also rise with de-escalation [19,20]; but, this risk is relatively low, and it is outweighed by the possible benefits of antibiotic de-escalation [19,20]. Antibiotic de-escalation is a complex procedure that needs a great deal of preparation and coordination. However, it is crucial to identify the perfect time to de-escalate, pick the appropriate medications, and keep a watchful eye out for infection symptoms in the patient. Nevertheless, antibiotic de-escalation can be an effective and safe method of enhancing the rational use of antibiotics and can promote antimicrobial stewardship activities when carried out appropriately [21].

By thoroughly analyzing the current literature on the implications of antibiotic de-escalation in patients on antibiotic use, duration of hospital stays, mortality, and cost, this systematic review and meta-analysis aim to fill this gap. The results of this study will help to update clinical practice recommendations for the proper use of antibiotics and offer insightful information about the efficacy of antibiotic de-escalation. Finally, this study can help to address the rising threat of ABR, lower healthcare costs, and can enhance patient outcomes [22,23,24].

2. Results

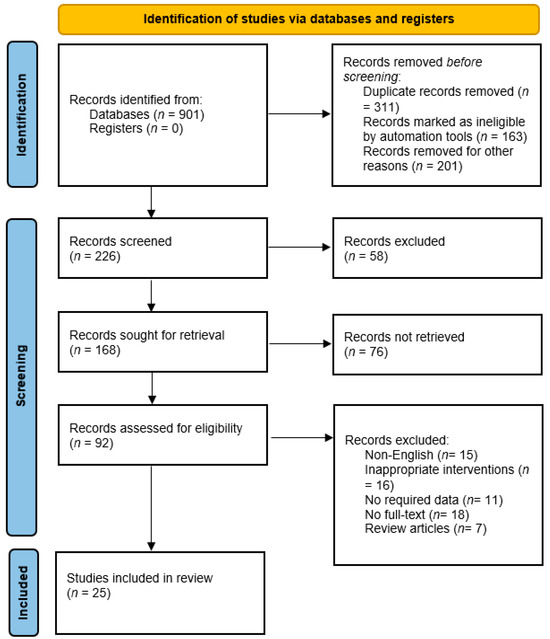

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review that included searches of databases is shown in Figure 1. In the first stage, the search strategy identified 901 potentially relevant records from various databases based on the search strategy. The next stage involved removing any duplicate records identified from the initial search (n = 311), records marked as ineligible by automation tools (n = 163), and records removed for other reasons (n = 201). This left 226 records for screening. At the records screening stage, 226 records were screened based on their titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies. Among the 226 records that were screened, 58 records were excluded at this stage based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the systematic review. The remaining 168 records were obtained in full-text format for further assessment of eligibility. Among the 168 records sought for retrieval, 76 records were not retrieved due to various reasons such as unavailability or access restrictions. The 92 records retrieved were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the systematic review. Based on the assessment of eligibility, 67 records were excluded from the review. The reasons for exclusion included non-English language (n = 15), inappropriate interventions (n = 16), no required data (n = 11), no full-text available (n = 18), and review articles (n = 7). Finally, a total of 25 studies were included in the systematic review, which met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were relevant to the research question, and among these, 7 studies were conducted in pediatrics and the remaining studies were conducted in adult patients.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of included studies.

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the characteristics and results of six prospective studies and one retrospective study related to antibiotic de-escalation in pediatric patients. The studies were conducted in different countries, settings, and patient populations. The reported de-escalation rate ranged from 28% to 98.5%, with most studies reporting a de-escalation rate above 50%. The endpoints measured in the studies included antimicrobial utilization, length of stay, infection-related mortality, duration of antibiotic use, therapy efficacy, prevalence of acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, clinical success rate, and mortality rate. The type of antibiotics used for de-escalation varied among the studies, and included cephalosporins, carbapenems, penicillin, and gentamicin. The study duration and sample size varied among the studies, ranging from a few months to several years, and from 140 to 1838 patients. The studies were conducted in different healthcare settings, including pediatric ICUs, neonatal ICUs, general units, oncology units, and bone marrow transplant units, indicating that de-escalation therapy can be applied in different healthcare settings. Taken together, the results showed a decline in consumption of antibiotics in the de-escalation group compared to the non-de-escalation group, with differences ranging from −236 to −1.1 days of therapy per 1000 patients. For example, Han et al. (2013) showed a decrease of 15.7 percentage points in the de-escalation group compared to the non-de-escalation group [25]. De-escalation was associated with a decrease in mean length of stay in some studies, such as the study by Han et al. (2013) where the de-escalation group had a mean length of stay that was 4.6 days shorter than the non-de-escalation group [25]. The studies had mixed results on the impact of de-escalation on overall costs. Some studies, such as the study by Renk et al. (2020), showed a decrease in costs in the de-escalation group compared to the non-de-escalation group [26]. The overall cost was United State Dollar (USD) 4688 in the non-de-escalation group and USD 3463 in the de-escalation group, with a difference of USD 1225. Most of other studies did not report any significant difference in costs.

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the characteristics and results of antibiotic de-escalation in adult patients. The de-escalation rate varied depending on the study population and the definition of de-escalation. The de-escalation rate ranged from 12.9% to 96.2% in the 16 studies. On the one hand, Viasus et al. (2017) reported a de-escalation rate of 12.9% in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) treated with beta-lactam antibiotics in a retrospective study conducted in Spain [27]. On the other hand, Lim et al. (2021) reported a de-escalation rate of 96.2% in a retrospective study conducted in Malaysia among patients in the ICU treated with carbapenems and vancomycin [28]. Tah et al. (2022) reported a 73.3% survival rate in a retrospective study conducted in Malaysia among patients with CAP and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) treated with carbapenems, colistin, and vancomycin [29]. Loon et al. (2018) reported an 86.9% de-escalation rate in a prospective study conducted in Malaysia among patients in medical wards treated with cephalosporins, piperacillin/tazobactam, and carbapenems [30]. Deshpande et al. (2021) reported a de-escalation rate of less than 50% among patients with pneumonia in a retrospective study conducted in 164 hospitals in the USA [31]. Morgan et al. (2012) reported a 30.43% antibiotics utilization rate in a retrospective study conducted in six hospitals in the USA [32]. Overall, the de-escalation group had a shorter duration of antibiotic therapy, shorter length of stay, and lower overall costs than the non-de-escalation group. This suggests that de-escalation can be used to reduce the amount of antibiotics that patients receive, without compromising patient outcomes. Viasus et al. (2017) found that antibiotic de-escalation led to a decrease in the number of days of therapy and mortality rates, as well as a shorter length of stay, although they did not report on overall costs [27]. Morgan et al. (2012) did not report on the effect of antibiotic de-escalation on mortality rates, but found that it led to a shorter length of stay, although it resulted in a higher overall cost [32]. The results of the quality assessment of the studies are mentioned in Table 5.

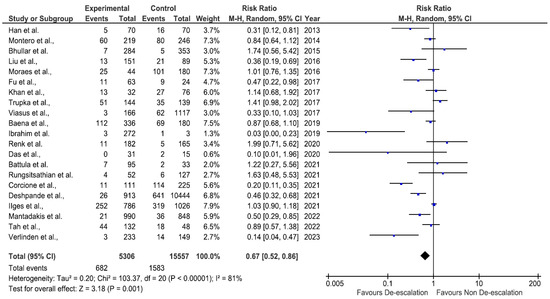

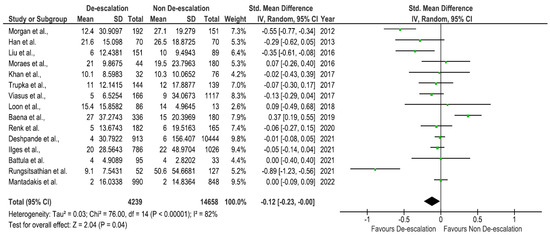

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the results of the meta-analysis. First, we evaluated the impact of de-escalation on overall mortality. A total of 21 studies provided the data on mortality, and 15 studies provided the data on length of hospital stay. The overall mortality was 10.8%. Our pooled analysis for mortality reported that a significant difference was observed between the de-escalation group and the non-de-escalation group in a random effect model (RR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.52–0.86, p = 0.001) (Figure 2). The mortality rates documented in the included studies showed substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 81%). Among 21 studies, 13 studies showed lower mortality rates in the de-escalation group as compared to the de-escalation group. In contrast, eight studies reported that de-escalation was associated with increased risk of mortality. The length of stay (LOS) was statistically lower in the de-escalation group than in the non-de-escalation group (p = 0.04). On average, the mean LOS of 15.6 days in the non-de-escalation group decreased to 11.5 days in the de-escalation group. However, in three studies, an increase in LOS was reported. Figure 3 depicts the forest plot of the difference between the de-escalation group and the non-de-escalation group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in pediatrics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies in pediatrics.

| Author and Year | Country | Study Design | Study Duration | Settings | Sample Size | Condition of Patients | De-Escalation Definition | Type of Empirical Antibiotics Used | Endpoints Measured | Reported De-Escalation Rate * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renk et al., 2020 [26] | Germany | Prospective study | 2017–2018 | PICU | 347 | Mixed | Not specified | Cefazolin Meropenem Vancomycin | Antimicrobial utilization Length of stay Infection related mortality | 28.0% |

| Battula et al., 2021 [33] | India | Prospective study | January 2019–June 2019 | PICU | 247 | Sepsis | Specified | Cephalosporins Carbapenems | Antimicrobial utilization Length of stay Infection related mortality | 38.4% |

| Bhullar et al., 2015 [34] | India | Prospective study | June 2013–March 2014 | PICU | 637 | Mixed | Not specified | Piperacillin Meropenem linezolid | Duration of antibiotic used | 34.6% |

| Han et al., 2013 [25] | China | Prospective study | February 2012–February 2017 | PICU | 140 | Pneumonia | Not specified | Not stated | Therapy efficacy Length of stay Duration of antibiotic used | 50.0% |

| Rungsitsathian et al., 2021 [35] | Thailand | Prospective study | March–December 2019 | General Units, Oncology Unit and ICU | 225 | Mixed | Specified | Meropenem | Clinical success rate. Prevalence of acquisition of CR-GNB | 57.8% |

| Mantadakis et al., 2022 [36] | Greece | Prospective study | June 2016–November 2017 | Oncology and BMT units | 1838 | Febrile neutropenia | Not specified | Amikacin/Gentamicin Cefepime Ceftriaxone/cefotaxime | Clinical success rate Mortality rate Length of ICU stay | 53.5% |

| Ibrahim et al., 2019 [37] | Malaysia | Prospective study | September 2017–December 2017 | NICU | 276 | EOS | Specified | Penicillin/gentamicin Penicillin/amikacin Ampicillin/gentamicin | Neonatal risk factors Maternal risk factors Length of ICU stay | 98.5% |

PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; EOS, early onset sepsis; CR-GNB, carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli; ICU, intensive care unit; BMT, bone marrow transplant. * De-escalation rate is based on the number patients involved in the de-escalation group.

Table 2.

Overview of the studies on pediatrics with the results on antibiotic consumption, mortality rates, mean length stay, and overall costs.

Table 2.

Overview of the studies on pediatrics with the results on antibiotic consumption, mortality rates, mean length stay, and overall costs.

| Study and Year | Days of Antibiotic Therapy DOT/1000 Patients | Mortality Rates | Mean Length of Stay | Overall Costs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-De-Escalation Group (Days) | De-Escalation Group (Days) | Differences in Percentage Points (Days) | Non-De-Escalation Group N (%) | De-Escalation Group N (%) | Differences in Percentage Points (%) | Non-De-Escalation Group (Days) | De-Escalation Group (Days) | Differences in Days | Non-De-Escalation Group (in USD) | De-Escalation Group (in USD) | Differences in Costs | |

| Renk et al., 2020 [26] | 1569 | 1333 | −236 | 5 (3.0%) | 11 (6.0%) | 3.0% | 6 | 5 | −1 | 4688 | 3463 | −1225 |

| Battula et al., 2021 [33] | Not stated | Not stated | - | 2 (6.0%) | 7 (7.3%) | 1.3% | 4 | 4 | 0 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Bhullar et al., 2015 [34] | 7.4 | 6.3 | −1.1 | 5 (1.4%) | 7 (2.4%) | 1.0% | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Han et al., 2013 [25] | 18.8 | 14.6 | −4.2 | 16 (22.8%) | 5 (7.1%) | −15.7% | 26.5 | 21.9 | −4.6 | 2193 | 1297 | −896 |

| Rungsitsathian et al., 2021 [35] | 50.6 | 11 | −39.6 | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (7.6%) | 2.9% | 50.6 | 9.1 | −41.5 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Mantadakis et al., 2022 [36] | 517 | 501 | −16 | 36 (4.2%) | 21 (2.1%) | −2.1% | 2 | 2 | 0 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Ibrahim et al., 2019 [37] | 3.9 | 2.2 | −1.7 | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (1.1%) | −32.2% | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

DOT, days of therapy; USD, United State Dollar.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies in adults.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies in adults.

| Author and Year | Country | Study Design | Study Duration | Settings | Sample Size | Condition of Patients | De-Escalation Definition | Type of Antibiotics Used | Endpoints Measured | Reported De-Escalation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viasus et al., 2017 [27] | Spain | Retrospective study | February 1995–December 2014 | Emergency department | 1283 | CAP | Specified | Beta-lactams | Mortality rate Length of stay Antibiotics utilization | 12.9% |

| Tah et al., 2022 [29] | Malaysia | Retrospective study | January 2016–July 2019 | Medical wards | 180 | CAP and HAP | Specified | Carbapenems, colistin, and vancomycin | Mortality rate Survival rate | 73.3% |

| Fu et al., 2017 [38] | China | Retrospective study | 2006–2015 | Tertiary care hospital | 87 | Severe Aplastic anemia | Specified | Not stated | Mortality rate Survival rate | 72.41% |

| Verlinden et al., 2023 [39] | Belgium | Retrospective study | November 2011–February 2021 | Hematology ward | 958 | Mixed | Specified | Amikacin, meropenem, and piperacillin/tazobactam | Infection related ICU admission Mortality rate Antibiotics utilization | - |

| Morgan et al., 2012 [32] | USA | Retrospective study | September 2009–October 2010 | 6 Hospitals | 631 | Mixed | Not specified | Cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and penicillin | Antibiotics utilization | 30.43% |

| Deshpande et al., 2021 [31] | USA | Retrospective study | 2010–2015 | 164 Hospitals | 14,170 | Pneumonia | Specified | Not stated | Length of stay Healthcare costs Antibiotic utilization | <50% |

| Loon et al. 2018 [30] | Malaysia | Prospective study | July 2017–September 2017 | Medical wards | 99 | Mixed | Not specified | Cephalosporins, piperacillin/tazobactam, and carbapenems | Length of stay Antibiotic utilization | 86.9% |

| Liu et al., 2016 [40] | USA | Retrospective study | January 2011–December 2011 | Medical center | 240 | Mixed | Specified | Vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam | Length of stay Antibiotic utilization | 63.0% |

| Lim et al., 2021 [28] | Malaysia | Retrospective study | November 2018–November 2019 | ICU | 382 | Mixed | Not specified | Carbapenems and vancomycin | Antibiotic utilization Isolation of pathogens in ICU | 96.2% |

| Corcione et al., 2021 [41] | Italy | Retrospective study | January 2016–November 2017 | Emergency department | 336 | Mixed | Not specified | Not stated | Frequency of ADE Length of stay In-hospital mortality | 33.03% |

| Khan et al., 2017 [13] | Malaysia | Retrospective study | January 2012–December 2014 | ICU | 108 | VAP | Specified | Carbapenems, colistin, and cefepime | Mortality rate Length of ICU stay | 42.1% |

| Singh et al., 2019 [42] | India | Prospective study | June 2017–December 2017 | ICU | 75 | Mixed | Specified | Colistin, carbapenems, and piperacillin/tazobactam | Adequacy of antibiotic therapy Culture positivity rates | 24% |

| Trupka et al., 2017 [43] | USA | Prospective study | January 2016–December 2016 | ICU | 283 | Pneumonia | Specified | Carbapenems, quinolones and cephalosporins | Mortality rate Length of ICU stay Antibiotic utilization | 50.9% |

| Ilges et al., 2021 [44] | USA | Retrospective study | 2016–2019 | Medical center | 1812 | Pneumonia | Specified | Not stated | Mortality rate Length of ICU stay Onset of infection | 43.37% |

| Das et al., 2020 [45] | India | Retrospective study | July 2018–September 2018 | ICU | 83 | Mixed | Not specified | Carbapenem, glycopeptides, and monobactam | Clinical success rate Length of hospital stay | 55.4% |

| Montero et al., 2014 [46] | Spain | Prospective study | January 2008–May 2012 | ICU | 712 | Sepsis and septic shock | Specified | Not stated | Length of hospital stay Mortality rate | 34.9% |

| Baena et al., 2019 [47] | Spain | Prospective study | January 2012–December 2013 | 13 hospitals | 516 | Bacteremia | Specified | Piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems, and cephalosporins | Length of hospital stay Mortality rate Clinical success rate | 65.1% |

| Moraes et al., 2016 [48] | Brazil | Prospective study | April 2013–September 2013 | Tertiary care hospital | 224 | Severe sepsis | Specified | Not stated | Antibiotic adequacy Culture positivity Mortality rate Length of hospital stay | 19.6% |

CAP, community acquired pneumonia; VAP, ventilator-acquired pneumonia; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 4.

Overview of the studies in adults with the results on antibiotic consumption, mortality rates, mean length stay, and overall costs.

Table 4.

Overview of the studies in adults with the results on antibiotic consumption, mortality rates, mean length stay, and overall costs.

| Study and Year | Day of Antibiotic Therapy DOT/1000 Patients | Mortality Rates | Mean Length of Stay | Overall Costs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-De-Escalation Group (Days) | De-Escalation Group (Days) | Differences in Percentage Points (Days) | Non-De-Escalation Group N (%) | De-Escalation Group N (%) | Differences in Percentage Points (%) | Non-De-Escalation Group (Days) | De-Escalation Group (Days) | Differences in Days | Non-De-Escalation Group (in USD) | De-Escalation Group (in USD) | Differences in Costs | |

| Viasus et al., 2017 [27] | 5 | 3 | −2 | 62 (5.5%) | 3 (1.8%) | −3.7 | 9 | 5 | −4 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Tah et al., 2022 [29] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 18 (37.5%) | 44 (33.3%) | −4.2 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Fu et al., 2017 [38] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 9 (37.5%) | 11 (17.4%) | −20.1 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Verlinden et al., 2023 [39] | 14 | 12 | −2 | 14 (9.3%) | 3 (1.2%) | −8.1 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Morgan et al., 2012 [32] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | - | 27.1 | 12.4 | −14.7 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Deshpande et al., 2021 [31] | 7 | 5 | −2 | 641 (6.1%) | 26 (2.8%) | −3.3 | 6 | 4 | −2 | 10,869 | 7855 | −3014 |

| Loon et al. 2018 [30] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | - | 14 | 15.4 | −1.4 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Liu et al., 2016 [40] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 21 (23.5%) | 13 (8.6%) | −14.9 | 10 | 6 | −4 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Lim et al., 2021 [28] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Corcione et al., 2021 [41] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 114 (50.6%) | 11 (9.9%) | −40.7 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Khan et al., 2017 [13] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 27 (35.5%) | 13 (40.6%) | 5.1 | 10.3 | 10.1 | −0.2 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Singh et al., 2019 [42] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Trupka et al., 2017 [43] | 7 | 7 | 0 | 35 (25.1%) | 51 (35.4%) | 10.3 | 12 | 11 | 1 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Ilges et al., 2021 [44] | 11 | 9 | −2 | 319 (31.0%) | 252 (32.0%) | 1 | 22 | 20 | −2 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Das et al., 2020 [45] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | −13.3 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Montero et al., 2014 [46] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 80 (32.5%) | 60 (27.3%) | −5.2 | Not stated | Not stated | - | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Baena et al., 2019 [47] | 15 | 27 | 12 | 69 (38.3%) | 112 (33.3%) | −5 | 15 | 27 | 12 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

| Moraes et al., 2016 [48] | 19.5 | 21 | 1.5 | 101 (56.1%) | 25 (56.8%) | 0.7 | 19.5 | 21 | 1.5 | Not stated | Not stated | - |

DOT, days of Therapy.

Table 5.

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing quality of included studies.

Table 5.

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing quality of included studies.

| Selection | Comparability | Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Representative of Sample A | Sample Size B | Non-Respondents C | Ascertainment of Exposure D | Comparability of Cohort Studies on Basis of Design E | Assessment of Outcomes F | Statistical Analysis G | Quality Score |

| Renk et al., 2020 [26] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Battula et al., 2021 [33] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Bhullar et al., 2015 [34] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Han et al., 2013 [25] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Rungsitsathian et al., 2021 [35] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Mantadakis et al., 2022 [36] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Ibrahim et al., 2019 [37] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Viasus et al., 2017 [27] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Tah et al., 2022 [29] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Fu et al., 2017 [38] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Verlinden et al., 2023 [39] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Morgan et al., 2012 [32] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | - | 5 |

| Deshpande et al., 2021 [31] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Loon et al. 2018 [30] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Liu et al., 2016 [40] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Lim et al., 2021 [28] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Corcione et al., 2021 [41] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Khan et al., 2017 [13] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Singh et al., 2019 [42] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | - | 5 |

| Trupka et al., 2017 [43] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Ilges et al., 2021 [44] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Das et al., 2020 [45] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | |

| Montero et al., 2014 [46] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Baena et al., 2019 [47] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Moraes et al., 2016 [48] | * | * | - | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

A*, truly representative or somewhat representative of average in target population; B*, drawn from the same community; C-, secured record or structured review; D*, Yes; D-, no; E*, study controls for age, gender, and other factors; F**, both record linkage and blind assessment; G*, follow-up of all subjects; G-, no follow-up of all subjects.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of mortality [13,25,27,29,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Figure 3.

Forest plot of length of stay [13,25,26,27,30,31,32,33,35,36,40,43,44,47,48].

3. Discussion

Antibiotic de-escalation is a possible and crucial component of ASP activity in patients to rationalize the use of antibiotics and to reduce the burden of ABR [49,50]. This systematic review and meta-analysis reveal promising insights into the practice of de-escalation across both pediatric and adult patient populations, highlighting its safety and potential benefits. In all the included studies, a significant number of patients were able to have their antibiotics de-escalated after initial therapy. This suggests that it is possible to use less intensive narrow-spectrum antibiotics in many cases, without compromising patient outcomes. The results suggest that de-escalation therapy can be effective in reducing the unnecessary use of reserve group antibiotics [51]. De-escalation therapy was also associated with improved clinical outcomes such as reduced length of stay, reduced mortality rate, and increased clinical success rate [52,53]. In most of the included studies, the de-escalation group had a shorter duration of antibiotic therapy than the non-de-escalation group, which can reduce the risk of side effects and ABR [3,54,55,56]. Furthermore, the economic implications of antibiotic de-escalation should not be overlooked. De-escalation can reduce the cost of antibiotic therapy, as narrower-spectrum antibiotics are typically less expensive than broad-spectrum antibiotics [57,58]. By embracing de-escalation practices, healthcare institutions can potentially reduce the financial burden associated with antibiotic therapy. However, it is essential to acknowledge that de-escalation rates exhibited variations across studies. The de-escalation rate varied depending on the study population and the definition of de-escalation. This variation is likely due to a number of factors, including the study population (e.g., PICU vs. NICU), the definition of de-escalation, and the severity of the infection [59,60]. Another intriguing aspect was the diversity in de-escalation methods employed in the included studies, highlighting the absence of a standardized approach in clinical practice. Achieving a consensus on the best strategies for de-escalation remains a challenge [19]. Successful implementation relies on close collaboration among healthcare providers to ensure careful patient monitoring and the flexibility to adjust antibiotic regimens as necessary [61,62]. This is because de-escalation requires careful monitoring of a patient’s response to therapy and a willingness to change the antibiotic regimen as needed. In addition, de-escalation can be challenging in patients with complex infections or those who are at high risk of complications [63,64].

Despite the challenges, antibiotic de-escalation is a promising strategy for reducing the risk of ABR [19,21]. As the global problem of antibiotic resistance continues to grow, it is important to find ways to reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics. Antibiotic de-escalation is one such strategy that has the potential to make a significant impact on the problem of ABR [65]. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are akin to a blunt instrument, affecting a wide array of bacteria, including beneficial ones, and providing an environment where resistant strains can thrive [66]. In contrast, de-escalation selects for less resistant bacterial strains, limiting the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant genes. This practice not only preserves the effectiveness of antibiotics currently in use but also extends the lifespan of these vital drugs, ensuring they remain a valuable resource in our ongoing fight against ABR [67]. Nevertheless, early diagnosis is a critical component of effective antibiotic de-escalation and ABR mitigation [10,11]. It empowers healthcare providers to make informed treatment decisions, optimize antibiotic use, improve patient outcomes, and to contribute to the global effort to combat antibiotic resistance [68].

Several limitations are highlighted in light of the findings of this systematic review. The studies that were included had a variety of research designs, subjects, and interventions. The results of the meta-analysis may have been more difficult to interpret because of this heterogeneity. Second, the included studies were mostly of a brief duration. Thirdly, depending on the type of infection, the patient’s underlying medical conditions, and the type of antibiotic that is being de-escalated, the effect of antibiotic de-escalation on patient outcomes may vary. Additionally, different studies use different definitions of antibiotic de-escalation, making it challenging to compare the findings of various studies. To discover the best strategy for antibiotic de-escalation and to pinpoint the risk factors, more study is required.

4. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were carried out in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 recommendations by utilizing its checklist.

4.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was carried out using electronic databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science, from inception to April 2023. The search terms used were “antibiotic de-escalation”, “antibiotic stewardship”, “narrow-spectrum antibiotics”, “broad-spectrum antibiotics”, “length of hospitalization”, “mortality”, and “cost”. Related MeSH headings with “AND” or “OR” were also used. In addition, the reference lists of identified studies and relevant review articles were manually screened for additional studies. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian. The search strategy was updated on a regular basis to ensure that all relevant studies were identified.

4.2. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria for including studies in this review were as follows:

Studies published in English;

Studies that evaluated the impact of antibiotic de-escalation on antibiotic consumption, length of hospitalization, mortality, or cost in hospitalized adult patients;

Studies that compared de-escalation with continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics or no change in antibiotic therapy;

Full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals conducted in humans.

Studies were excluded if they were abstracts, conference proceedings, letters to the editor, or case reports.

4.3. Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies for eligibility. Full-text articles were retrieved for potentially eligible studies, and data were extracted using a standardized form. Data extracted included author and year, country, study design, study duration, setting, population characteristics, sample size, intervention and control details, condition of patients, de-escalation definition, type of antibiotics used, outcomes of interest, and reported de-escalation rate, as summarized in Table 1 which describes general characteristics. Table 2 contains specific information related to days of antibiotic therapy (DOT), DOT/1000 patients, mortality rates, mean length of stay, and overall costs. The first column lists the study’s name and year, and the second column presents the days of DOT per 1000 patients in both non-de-escalation and de-escalation groups. In the third column, the difference in DOT between the non-de-escalation and de-escalation groups is presented in percentage points and days. The fourth and fifth columns provide mortality rates in both non-de-escalation and de-escalation groups, respectively, presented as a percentage of the total number of patients. The difference in percentage points between the two groups is presented in column six. The seventh, eighth, and ninth columns present the mean length of stay in both non-de-escalation and de-escalation groups, the difference in days between the two groups, and the overall cost in US dollars, respectively. The last column reports the difference in costs between the two groups.

4.4. Quality Assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used for assessing the quality of the included studies. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

4.5. Meta-Analysis

The data retrieved from 25 articles were pooled and analyzed using the Revman-5, software version 5.4.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration). For dichotomous outcomes, the results were documented as the relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval, and the weighted mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated for continuous outcomes. Studies that assessed similar interventions in a similar population were evaluated for the presence of statistical heterogeneity by using a chi-square test and the heterogeneity within groups was assessed using I2 statistics (which indicated the proportion of total variation between studies that is due to heterogeneity in study design, patients, or interventions rather than chance). According to guidelines, I2 values greater than 50% indicated significant heterogeneity [69,70].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review showed that antibiotic de-escalation is associated with improved clinical outcomes and a decrease in antibiotic consumption, length of stay, and possibly costs in both pediatric and adult patients. The studies included in this review were conducted in various healthcare settings, indicating that de-escalation therapy can be applied in different healthcare settings. However, the de-escalation rate varied depending on the study population and definition of de-escalation. Despite this variation, the results of this systematic review support the importance of de-escalation as a strategy to optimize antibiotic therapy and to reduce the development of ABR. As the global healthcare community faces the ongoing challenge of ABR, embracing de-escalation practices within ASPs represents a critical step towards preserving the efficacy of antibiotics for future generations. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of de-escalation on patient outcomes and to standardize the definition of de-escalation to allow for better comparison of studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., A.A. (Abeer Aanazd) and M.A.; methodology, F.B. and F.A. (Farah Althikrallah); software, validation, N.A. (Nada Alahmari), N.A. (Noor Abdulrahim) and M.B.; formal analysis, F.A. (Fatimah Alotaibi); investigation, R.A., J.A.B., A.A. (Amal Almalki) and K.A. (Khalid Albalawi); resources, A.A. (Amal Almalki); data curation, N.A. (Noor Abdulrahim), F.B., N.A. (Nada Alahmari) and F.A. (Farah Althikrallah); writing—original draft preparation, A.K., K.A. (Khalid Albalawi), A.A. (Abeer Aanazi) and F.A. (Farah Althikrallah); writing—review and editing, N.A. (Noor Abdulrahim), N.A. (Nada Alahmari), A.A. (Abeer Aanazi), M.K. and K.A. (Khalid Albalawi); visualization, F.A. (Fatimah Alotaibi) and K.A. (Khalid Alsaedi); supervision, F.A. (Fatimah Alotaibi) and K.A. (Khalid Alsaedi); project administration, A.A. (Amal Almalki) and K.A. (Khalid Alsaedi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hamilton, K.W. Miracle Cure: The Creation of Antibiotics and the Birth of Modern Medicine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.-X.; Fang, Z.; Min, R.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Fang, P.-Q. Is nationwide special campaign on antibiotic stewardship program effective on ameliorating irrational antibiotic use in China? Study on the antibiotic use of specialized hospitals in China in 2011–2012. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2014, 34, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- Karakonstantis, S.; Kalemaki, D. Antimicrobial overuse and misuse in the community in Greece and link to antimicrobial resistance using methicillin-resistant S. aureus as an example. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carey, B.; Cryan, B. Antibiotic misuse in the community—A contributor to resistance? Ir. Med. J. 2003, 96, 43–44, 46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pulingam, T.; Parumasivam, T.; Gazzali, A.M.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Chee, J.Y.; Lakshmanan, M.; Chin, C.F.; Sudesh, K. Antimicrobial resistance: Prevalence, economic burden, mechanisms of resistance and strategies to overcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 170, 106103. [Google Scholar]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial resistance: Implications and costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlam, T.F.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Abbo, L.M.; MacDougall, C.; Schuetz, A.N.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Dellit, T.H.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Fishman, N.O. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e51–e77. [Google Scholar]

- Lorgelly, P.K.; Atkinson, M.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Smyth, A.R.; Vyas, H.; Weston, V.; Stephenson, T. Oral versus iv antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children: A cost-minimisation analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 35, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, E.; Cavalieri, S.J.; Elsasser, G.N.; Preheim, L.C.; Gonitzke, A.; Destache, C.J. Does antibiotic de-escalation for nosocomial pneumonia impact intensive care unit length of stay? Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2013, 21, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kalungia, A.C.; Mwambula, H.; Munkombwe, D.; Marshall, S.; Schellack, N.; May, C.; Jones, A.S.C.; Godman, B. Antimicrobial stewardship knowledge and perception among physicians and pharmacists at leading tertiary teaching hospitals in Zambia: Implications for future policy and practice. J. Chemother. 2019, 31, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Walley, J.D.; Hicks, J.P.; Zeng, J.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; Newell, J.N.; Sun, Q. Effect of a training and educational intervention for physicians and caregivers on antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in children at primary care facilities in rural China: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1258–e1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabah, A.; Cotta, M.O.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Schouten, J.; Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J.; Tacey, M.; Timsit, J.-F.; Leone, M.; Zahar, J.R. A systematic review of the definitions, determinants, and clinical outcomes of antimicrobial de-escalation in the intensive care unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.A.; Aziz, Z. A retrospective study of antibiotic de-escalation in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia in Malaysia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshareef, H.; Alfahad, W.; Albaadani, A.; Alyazid, H.; Talib, R.B. Impact of antibiotic de-escalation on hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections: A retrospective cohort single center study. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evodia, E.; Myrianthefs, P.; Prezerakos, P.; Baltopoulos, G. Antibiotic costs in bacteremic and nonbacteremic patients treated with the de-escalation approach. Crit. Care 2008, 12, P15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hajiabdolbaghi, M.; Makarem, J.; Salehi, M.; Manshadi, S.A.D.; Mohammadnejad, E.; Mazaherpoor, H.; Seifi, A. Does an antimicrobial stewardship program for Carbapenem use reduce Costs? An observation in Tehran, Iran. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 11, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Durojaiye, O.C.; Bell, H.; Andrews, D.; Ntziora, F.; Cartwright, K. Clinical efficacy, cost analysis and patient acceptability of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT): A decade of Sheffield (UK) OPAT service. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Dickstein, Y.; Raz-Pasteur, A. Antibiotic de-escalation for bloodstream infections and pneumonia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterton, R.G. Antibiotic de-escalation. Crit. Care Clin. 2011, 27, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerther, P.-L.; Barbier, F.; Lepeule, R.; Fihman, V.; Ruppé, É. Assessing the ecological benefit of antibiotic de-escalation strategies to elaborate evidence-based recommendations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1128–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campion, M.; Scully, G. Antibiotic use in the intensive care unit: Optimization and de-escalation. J. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 33, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.F.; Cowling, B.J.; Feng, S.; Aso, H.; Wu, P.; Fukuda, K.; Seto, W.H. Impact of antibiotic stewardship programmes in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshed, S.; Padzil, F.; Shamsudin, S.H.; Bux, S.H.; Jamaluddin, A.A.; Bhagavathula, A.S. Antibiotic Stewardship in Community Pharmacies: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyles, T.H.; Whitelaw, A.; Bamford, C.; Moodley, M.; Bonorchis, K.; Morris, V.; Rawoot, N.; Naicker, V.; Lusakiewicz, I.; Black, J. Antibiotic stewardship ward rounds and a dedicated prescription chart reduce antibiotic consumption and pharmacy costs without affecting inpatient mortality or re-admission rates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Feng, R.; Meng, J. Treatment of severe pediatric pneumonia by antibiotic de-escalation therapy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 2610–2616. [Google Scholar]

- Renk, H.; Sarmisak, E.; Spott, C.; Kumpf, M.; Hofbeck, M.; Hölzl, F. Antibiotic stewardship in the PICU: Impact of ward rounds led by paediatric infectious diseases specialists on antibiotic consumption. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viasus, D.; Simonetti, A.F.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Niubó, J.; Dorca, J.; Carratalà, J. Impact of antibiotic de-escalation on clinical outcomes in community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Kuai, C.C.; Lim, C.H. Antibiotic De-escalation Practice in General Intensive Care Unit Penang General Hospital. J. Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 2021, 7, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, H.L.; Abdullah, S.; Ghazali, A.K.; Khan, R.A.; Ramadas, A.; Leong, C.L. Impact of extended and restricted antibiotic deescalation on mortality. Antibiotics 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loon, W.K.; Ling, W.M.; Kai, C.Z.; Ganasen, S.M.; Hasbullah, W.S.W.; Hui, C.S.; Soo, C.T.; Nim, L.K.; Shyan, W.P. A Prospective Study on Antibiotic De-escalation Practice in the Medical Wards of Penang General Hospital. Pharm. Res. Rep. 2018, 1, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, A.; Richter, S.S.; Haessler, S.; Lindenauer, P.K.; Yu, P.-C.; Zilberberg, M.D.; Imrey, P.B.; Higgins, T.; Rothberg, M.B. De-escalation of empiric antibiotics following negative cultures in hospitalized patients with pneumonia: Rates and outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.J.; Schweizer, M.L.; Braykov, N.B.; Weisenberg, S.A.; Uslan, D.Z.; Kelesidis, T.; Young, H.; Cantey, J.B.; Septimus, E.J.; Srinivasan, A.; et al. The Frequency of Antibiotic De-Escalation Over Six US Hospitals: Results from a Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. OneHealth Trust 2012, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Battula, V.; Krupanandan, R.K.; Nambi, P.S.; Ramachandran, B. Safety and feasibility of antibiotic de-escalation in critically ill children with sepsis—A prospective analytical study from a pediatric ICU. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 640857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, H.S.; Shaikh, F.A.R.; Deepak, R.; Poddutoor, P.K.; Chirla, D. Antimicrobial justification form for restricting antibiotic use in a pediatric intensive care unit. Indian Pediatr. 2016, 53, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungsitsathian, K.; Wacharachaisurapol, N.; Nakaranurack, C.; Usayaporn, S.; Sakares, W.; Kawichai, S.; Jantarabenjakul, W.; Puthanakit, T.; Anugulruengkitt, S. Acceptance and outcome of interventions in a meropenem de-escalation antimicrobial stewardship program in pediatrics. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantadakis, E.; Kopsidas, I.; Coffin, S.; Dimitriou, G.; Gkentzi, D.; Hatzipantelis, E.; Kaisari, A.; Kattamis, A.; Kourkouni, E.; Papachristidou, S. A national study of antibiotic use in Greek pediatric hematology oncology and bone marrow transplant units. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Bakry, M.M.; See, K.C.; Tahir, N.A.M.; Shah, N.M. Early Empiric Antibiotic De-escalation in Suspected Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 81, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Chen, T.; Song, J.; Wang, G.; Li, L.; Ruan, E.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xing, L. De-escalation empirical antibiotic therapy improved survival for patients with severe aplastic anemia treated with antithymocyte globulin. Medicine 2017, 96, e5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinden, A.; Jansens, H.; Goossens, H.; Anguille, S.; Berneman, Z.N.; Schroyens, W.A.; Gadisseur, A.P. Safety and efficacy of antibiotic de-escalation and discontinuation in high-risk hematological patients with febrile neutropenia: A single-center experience. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ohl, C.; Johnson, J.; Williamson, J.; Beardsley, J.; Luther, V. Frequency of empiric antibiotic de-escalation in an acute care hospital with an established antimicrobial stewardship program. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcione, S.; Mornese Pinna, S.; Lupia, T.; Trentalange, A.; Germanò, E.; Cavallo, R.; Lupia, E.; De Rosa, F.G. Antibiotic De-escalation experience in the setting of emergency department: A retrospective, observational study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Azim, A.; Gurjar, M.; Poddar, B.; Baronia, A.K. Audit of antibiotic practices: An experience from a tertiary referral center. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trupka, T.; Fisher, K.; Micek, S.T.; Juang, P.; Kollef, M.H. Enhanced antimicrobial de-escalation for pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: A cross-over study. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilges, D.; Ritchie, D.J.; Krekel, T.; Neuner, E.A.; Hampton, N.; Kollef, M.H.; Micek, S. Assessment of antibiotic de-escalation by spectrum score in patients with nosocomial pneumonia: A single-center, retrospective cohort study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Haque, I.; Gaur, A.; Mustafa, M.S. De-Escalation Pattern of Antibiotics in the Medical Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Care Hospital in North India. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 9, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Garnacho-Montero, J.; Gutiérrez-Pizarraya, A.; Escoresca-Ortega, A.; Corcia-Palomo, Y.; Fernandez-Delgado, E.; Herrera-Melero, I.; Ortiz-Leyba, C.; Márquez-Vácaro, J.A. De-escalation of empirical therapy is associated with lower mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Baena, Z.R.; Delgado-Valverde, M.; Valiente Méndez, A.; Almirante, B.; Gómez-Zorrilla, S.; Borrell, N.; Corzo, J.E.; Gurguí, M.; De la Calle, C.; García-Álvarez, L. Impact of de-escalation on prognosis of patients with bacteremia due to Enterobacteriaceae: A post hoc analysis from a multicenter prospective cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, R.B.; Guillén, J.A.V.; Zabaleta, W.J.C.; Borges, F.K. De-escalation, adequacy of antibiotic therapy and culture positivity in septic patients: An observational study. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva 2016, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cui, K.; Wang, T.; Dong, H.; Feng, W.; Ma, C.; Dong, Y. Trends in and correlations between antibiotic consumption and resistance of Staphylococcus aureus at a tertiary hospital in China before and after introduction of an antimicrobial stewardship programme. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Huttner, B.; Moja, L.; Pulcini, C.; Zeng, M.; Mendelson, M.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.; Magrini, N. Encouraging AWaRe-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use—The new 2019 Essential Medicines List becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, I.; Versporten, A.; Drapier, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Goossens, H. Hospital antibiotic prescribing patterns in adult patients according to the WHO Access, Watch and Reserve classification (AWaRe): Results from a worldwide point prevalence survey in 69 countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1614–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollef, M.H.; Micek, S.T. Rational use of antibiotics in the ICU: Balancing stewardship and clinical outcomes. JAMA 2014, 312, 1403–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nausheen, S.; Hammad, R.; Khan, A. Rational use of antibiotics—A quality improvement initiative in hospital setting. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2013, 63, 60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slama, T.G.; Amin, A.; Brunton, S.A.; File, T.M.; Milkovich, G.; Rodvold, K.A.; Sahm, D.F.; Varon, J.; Weiland, D. A clinician’s guide to the appropriate and accurate use of antibiotics: The Council for Appropriate and Rational Antibiotic Therapy (CARAT) criteria. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118 (Suppl. S7), 1S–6S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, M.; Hussain, M. Need and duration of antibiotic therapy in clean and clean contaminated operations. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2002, 52, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayukekbong, J.A.; Ntemgwa, M.; Atabe, A.N. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: Causes and control strategies. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillotson, G.S.; Zinner, S.H. Burden of antimicrobial resistance in an era of decreasing susceptibility. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, V.; Ruhe, J.J.; Lerner, P.; Fedorenko, M. Risk factors for readmission in patients discharged with outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, X.; Bai, J.; Gong, Y.; Lu, Z. Factors associated with doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use in China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magedanz, L.; Silliprandi, E.M.; dos Santos, R.P. Impact of the pharmacist on a multidisciplinary team in an antimicrobial stewardship program: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012, 34, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, C.; Polk, R.E. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health care systems. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 18, 638–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Yahav, D.; Carmeli, Y.; Benattar, Y.D.; Skiada, A.; Andini, R.; Eliakim-Raz, N.; Nutman, A. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.; Del Bono, V.; Trecarichi, E.; De Rosa, F.G.; Giannella, M.; Bassetti, M.; Bartoloni, A.; Losito, A.; Corcione, S.; Bartoletti, M. Risk factors for bloodstream infections due to colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Results from a multicenter case-control-control study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, e1–e1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.X.; Cosgrove, S.E. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Efficacy and Implementation of Strategies to Address Antimicrobial Overuse and Resistance. Antimicrob. Steward. 2017, 2, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Süzük Yıldız, S.; Kaşkatepe, B.; Şimşek, H.; Sarıgüzel, F.M. High rate of colistin and fosfomycin resistance among carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Turkey. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2019, 66, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, N.R.; Atun, R.; Zhu, N.; Kulasabanathan, K.; Silva, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Knight, G.M.; Robotham, J.V. Estimating the burden of antimicrobial resistance: A systematic literature review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, E.; Ziegelmann, A.; Eckmanns, T.; Krause, G. Eliciting views on antibiotic prescribing and resistance among hospital and outpatient care physicians in Berlin, Germany: Results of a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Gopalan, R.; Berlin, J.A.; Matthews, D.R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991, 337, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R.; Cho, J.; Kapoor, S.; Orenstein, R.; Singh, S.; Pardi, D.S.; Khanna, S. Low risk of primary Clostridium difficile infection with tetracyclines: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).