Simple Summary

Campylobacter spp. are important zoonotic pathogens in companion animals, and their rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a critical One Health issue. However, epidemiological data on feline Campylobacter carriage in Kelantan, Malaysia, remain scarce. This study investigated the occurrence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Campylobacter species in 150 rectal swab samples collected from 150 cats, both healthy and diseased. Approximately 35% of the cats harbored Campylobacter, with C. upsaliensis being the predominant species. Isolates exhibited high resistance to commonly used antibiotics, including amoxicillin, ampicillin, tetracycline, and erythromycin. These findings fill an epidemiological gap by providing the first baseline data on Campylobacter in cats in Kelantan, with direct implications for zoonotic transmission and regional AMR surveillance. The results indicate the urgent need for responsible antibiotic stewardship in veterinary practice and companion animal care, as indiscriminate use not only compromises animal health but also poses a significant public health concern through the potential spread of multidrug-resistant Campylobacter to humans.

Abstract

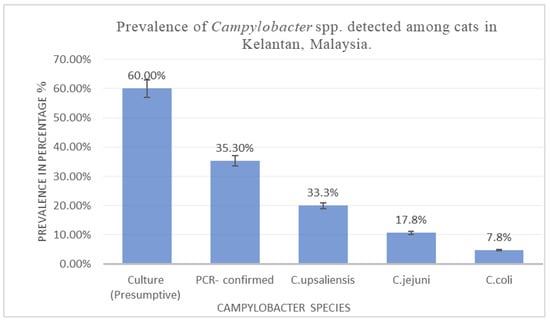

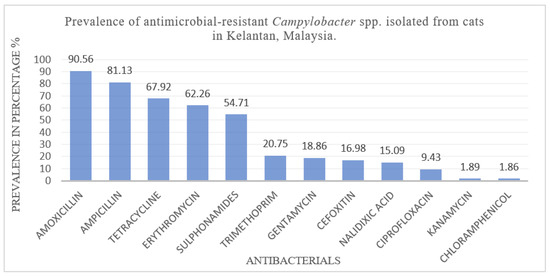

Campylobacter spp. are significant zoonotic pathogens, increasingly recognized for their role in the transmission of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) between animals and humans. This study aims to determine the occurrence, antimicrobial resistance profiles, and characterization of multidrug resistance indices of Campylobacter spp. isolated from domestic pets in Kelantan, Malaysia. Methods: Rectal swabs (n = 150) were collected from both healthy and diarrheic cats. Campylobacter spp. were isolated and confirmed by PCR, and antimicrobial susceptibility was assessed using the disk diffusion method. Results: Campylobacter spp. were detected in 35.3% of cats (53/150; SE = 0.04; 95% CI: 28.1–43.3%), with C. upsaliensis identified as the predominant species (33.3%; SE = 0.05; 95% CI: 24.5–43.6%), followed by C. jejuni (17.8%; SE = 0.04; 95% CI: 11.3–26.9%) and C. coli (7.8%; SE = 0.03; 95% CI: 3.8–15.2%). Isolates exhibited high resistance rates to amoxicillin (90.6%), ampicillin (81.1%), tetracycline (67.9%), erythromycin (62.3%), and sulphonamides (54.7%). Conclusion: The study reveals a substantial prevalence of Campylobacter spp. and notable levels of antimicrobial resistance among feline isolates, highlighting the zoonotic threat in Malaysia. These findings emphasize the importance of integrated surveillance and prudent antimicrobial stewardship under a One Health framework.

1. Introduction

Campylobacter spp. are spiral-shaped, motile, Gram-negative bacteria that thrive under microaerophilic conditions and are increasingly implicated in gastrointestinal disorders across species boundaries [1]. Among the various members of this genus, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli have traditionally dominated public health discourse due to their high zoonotic potential and frequent association with enteric disease in humans [2]. However, accumulating evidence indicates the emergence of less frequently studied species, such as Campylobacter upsaliensis and C. helveticus, particularly in companion animals like cats and dogs [3,4]. These animals often serve as subclinical carriers, enabling environmental dissemination and unnoticed transmission to human hosts via close physical interaction, shared living environments, or exposure to contaminated surfaces [5,6].

The ecological intimacy between humans and household pets has grown markedly in recent years, further blurring the interspecies barrier for zoonotic pathogens [7]. In Kelantan, Malaysia, cats occupy both indoor and semi-roaming ecological niches, which increases their likelihood of contact with contaminated environments, infected prey, and other free-roaming animals [8]. This ecological context is particularly relevant in Kelantan, where high human–animal density, close household interactions, and limited implementation of preventive veterinary care create conditions favorable for pathogen transmission. [9]. The infection risk is further heightened by the unapparent nature of carriage, which facilitates prolonged microbial shedding without overt clinical signs [1,8]. Compounding this concern is the documented escalation of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) within Campylobacter populations, driven by misuse of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine [10]. Increasing resistance to macrolides, fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, and tetracyclines has been reported in isolates from diverse hosts, significantly compromising treatment options and threatening public health security [10,11]. The resistance genes harbored by companion animal strains have the potential to disseminate horizontally, contributing to the broader resistome and exacerbating global AMR burdens [12,13]. Although the One Health framework emphasizes integrated surveillance across human, animal, and environmental sectors, companion animals have historically been underrepresented in AMR research initiatives, particularly in Southeast Asia [14,15].

Recent studies in Southeast Asia, including Malaysia, have documented the presence of multidrug-resistant Campylobacter in pets, with varying prevalence based on species, lifestyle, and exposure to environmental risk factors [16,17]. In Malaysia, pet ownership is steadily rising, with cats being among the most commonly kept domestic species, particularly in urban and semi-urban areas where veterinary care access and hygiene practices vary widely [18,19]. Although research has examined Campylobacter in dogs and livestock, data on the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles of feline isolates remain scarce, especially in the northeastern state of Kelantan [20,21]. To address this knowledge gap, the present study aimed to determine the occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in domestic cats in Kelantan, Malaysia; assess the antimicrobial resistance profiles of feline Campylobacter isolates; and characterize the multidrug resistance indices of the identified isolates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2023 to March 2024 in three districts of Kelantan, Malaysia (Kota Bharu, Bachok, and Kuala Krai), located on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Sampling was performed at various sites, including private veterinary clinics, community rescue shelters, and a veterinary teaching hospital. Rectal swabs were collected from cats whose owners or custodians provided informed consent after completing a standardized participation form were included. The study area is characterized by a humid tropical climate, with annual rainfall ranging from 2032 mm to 2540 mm. The wettest months occur from November to January, with ambient temperatures between 25 °C and 37 °C [22].

A total of 150 rectal swabs were obtained from domestic and stray cats across the selected districts, 50 samples per district, representative of the area collected. The frequency of collection was performed on a monthly basis. This sample size was determined based on population accessibility, estimated density of feline populations in urban and semi-urban settings, and the feasibility of sampling within the study timeframe. Additionally, the sample size was calculated using a simplified formula for cross-sectional studies:

where Z is the Z-score for 95% confidence (1.96), P is the expected prevalence of Campylobacter spp. (assumed at 20% based on prior studies), and d is the desired precision (0.07) [23]. The formula yielded a minimum sample size of 123, but to enhance statistical power and accommodate potential data exclusions, 150 samples were collected. The sampling decision was influenced by logistical practicality, ethical considerations, and accessibility of local cat populations, in line with recent regional studies involving Campylobacter spp. in companion animals [23,24]. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK/FPV/ACUE/PG/002/2023) and adhered to national animal research guidelines.

n = Z2P(1 − P)/d2,

2.2. Sample Collection

A total of 150 rectal swabs were collected from cats presented at veterinary clinics and hospitals across Kelantan, Malaysia. Pet owners were approached during routine visits and invited to participate voluntarily. Upon providing informed consent, participants were given a standardized questionnaire to complete. Rectal swab samples were obtained aseptically using sterile cotton-tipped applicators and immediately sealed in individual sterile plastic bags to prevent cross-contamination. The samples were subsequently placed in Cary-Blair transport medium and transported to the laboratory in a cooler box maintained at 4 °C. All specimens were processed within 24 h of arrival to ensure optimal recovery of microorganisms. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (Approval Code: UMK/FPV/ACUE/PG/002/2023).

2.3. Isolation and Identification of Campylobacter spp.

Rectal swabs were inoculated onto modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA) supplemented with selective agents and incubated at 42 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions, following protocols optimized for thermophilic Campylobacter. Colonies with typical morphology were subcultured onto blood agar for purification. Presumptive identification was performed based on Gram stain morphology, motility, and standard biochemical reactions (oxidase, catalase, urease, and hippurate hydrolysis) [25,26]. Confirmed isolates were preserved in Mueller–Hinton broth containing 20% glycerol and stored at −80 °C for long-term viability. Molecular confirmation of genus and species identity was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays targeting specific genetic markers, as described in previous studies [27].

2.4. PCR-Based Molecular Confirmation of Campylobacter spp.

The presence of Campylobacter spp. in phenotypically identified isolates was molecularly confirmed through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 16S rRNA gene, a highly conserved marker commonly employed for genus-level detection [28]. A reference control strain, Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 33560, kindly provided by the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, was included in each PCR run as a quality assurance benchmark.

PCR was conducted using previously validated genus-specific primers [29]. Each 25 µL reaction mixture comprised 12.5 µL of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 1 µL of forward primer (10 µM), 1 µL of reverse primer (10 µM), 5 µL of DNA template, and 5.5 µL of nuclease-free water. Amplification was carried out in a Bio-Rad T100™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following thermal protocol: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min; 30 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 20 s (denaturation), 58 °C for 20 s (annealing), and 72 °C for 60 s (extension); followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplicons were resolved by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels pre-stained with a nucleic acid-safe dye. Electrophoretic separation was conducted at 100 V for 45 min in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. A 100 bp DNA ladder (Promega, USA) was used to estimate molecular sizes of the amplified fragments. Primer sequences, expected amplicon sizes, and cycling parameters are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of primers used for the detection of Campylobacter spp.

2.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assessment

The resistance profiles of Campylobacter isolates were evaluated using the standard disk diffusion assay, performed on Mueller–Hinton agar enriched with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Oxoid, Manchester, UK), in accordance with the Kirby–Bauer method, although broth microdilution or E-test MICs are the gold standard for Campylobacter, these were not feasible in the current study due to resource limitations. Colonies exhibiting consistent morphology were selected from pure cultures and suspended in 10 mL of sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl). After thorough mixing, the bacterial suspension was adjusted to match the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard. Using a sterile cotton swab, 2 mL of the standardized suspension was uniformly spread across the agar surface. The plates were left to dry at ambient temperature for approximately five minutes before applying the antibiotic disks. Inoculated plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under controlled microaerophilic conditions.

Following incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones were measured using a digital caliper, and susceptibility interpretations were made in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints [34]. Each isolate was categorized as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on these criteria [34]. A panel of 12 antibiotics commonly used in both human and veterinary medicine in Malaysia was selected for testing. These included: ampicillin (10 µg), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (20/10 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), erythromycin (30 µg), kanamycin (30 µg), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (25 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), and sulfonamides (300 µg). The resistance profile (antibiogram) of each isolate was defined by its pattern of resistance, while the antibiogram length was calculated as the total number of antimicrobials to which resistance was observed [34].

2.6. Assessment of Multidrug Resistance and MAR Index

To assess resistance trends among the bacterial isolates, multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to three or more different classes of antimicrobial agents, following previously established guidelines as described by (Gaddafi et al., 2023) [35]. The extent of antimicrobial resistance was further quantified using the Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index, which was computed for each isolate by dividing the number of antibiotics to which resistance was observed by the total number of antibiotics included in the susceptibility panel. The MAR index serves as a proxy indicator for the level of antimicrobial exposure in the isolate’s environment. Values exceeding 0.2 are generally indicative of high-risk sources, such as settings where antimicrobial agents are widely used or improperly managed [36].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data entry was performed in Microsoft Excel, and all analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (v29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 5.5.2. Descriptive statistics summarized prevalence and resistance patterns, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), proportions were calculated using the Wilson method; exact (Clopper–Pearson) CIs were applied for small counts. Associations between categorical variables (e.g., host factors and resistance status) were assessed with Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate, while non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U, Kruskal–Wallis) compared continuous variables. Exact binomial tests were used to evaluate observed resistance proportions against reference values. Risk factors for resistance to ≥1 antimicrobial were further examined using multi-variable logistic regression, reporting adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CIs. Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and discriminatory power by the area under the ROC curve. For multiple comparisons, false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment was applied using the Benjamin–Hochberg method. In all tests, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of Campylobacter spp. in Feline Fecal Samples

In this investigation, a total of 150 rectal swabs collected from cats were analyzed. Of these, 90 samples (60.0%, SE = 0.04; 95% CI: 52.0–67.5%) exhibited phenotypic characteristics suggestive of Campylobacter spp., as determined through conventional culture techniques and morphological assessment (Table 2). To confirm the identity of the isolates, molecular analysis via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed. This approach verified the presence of Campylobacter DNA in 53 of the 90 presumptive isolates. Accordingly, the PCR-confirmed prevalence of Campylobacter spp. among the examined feline population was 35.3% (53/150; SE = 0.04; 95% CI: 28.1–43.3%). Species-level identification revealed that the predominant species was C. upsaliensis (30/53; 56.6% of PCR-positive isolates; SE = 0.07; 95% CI: 43.3–69.0%), followed by C. jejuni (16/53; 30.2%; SE = 0.06; 95% CI: 19.5–43.5%) and C. coli (7/53; 13.2%; SE = 0.05; 95% CI: 6.5–24.8%). When expressed relative to the total examined cat population (n = 150), the prevalence of C. upsaliensis, C. jejuni, and C. coli was (33.3%; SE = 0.05; 95% CI: 24.5–43.6%), followed by C. jejuni (17.8%; SE = 0.04; 95% CI: 11.3 –26.9%) and C. coli (7.8%; SE = 0.03; 95% CI: 3.8–15.2%), respectively (Figure 1). Species-level identification was achieved using species-specific PCR assays. Amplification of the cj0414 gene (161 bp) confirmed the presence of C. jejuni, while detection of the glyA gene (502 bp) and lpxA gene (86 bp) facilitated identification of C. coli and C. upsaliensis, respectively. Risk factors such as cats that had contact with other animals, semi-roamers, had unfiltered water, and had a history of antibiotic use were found in this study to be at a higher risk of Campylobacter infection.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. among cats (n = 150).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. detected among cats in Kelantan, Malaysia.

3.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Campylobacter Isolates

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on all 53 Campylobacter isolates using a panel of 12 antibiotics, revealing distinct resistance patterns (Figure 2). The isolates demonstrated the highest resistance to five antibiotics spanning four major classes. Resistance was most prevalent against amoxicillin (48/53), followed by ampicillin (43/53), tetracycline (36/53), erythromycin (33/53), and sulfonamides (29/53). Lower levels of resistance were observed for trimethoprim (11/53), gentamicin (10/53), cefoxitin (9/53), nalidixic acid (8/53), ciprofloxacin (5/53), and minimal resistance was found to kanamycin (1/53) and chloramphenicol (1/53). Overall, 90.56% (48/53) of the isolates exhibited resistance to at least one antibiotic class, while 67.92% (36/53) demonstrated multidrug resistance (MDR), defined as resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes. Among the 53 PCR-confirmed Campylobacter isolates, 81.1% (43/53) were resistant to at least one antimicrobial. To further explore determinants of resistance, host-related variables were analyzed. The prevalence of resistance to at least one antimicrobial and its association with risk factors are summarized in Table 3. The overall antimicrobial resistance profile of Campylobacter spp. isolates are presented in Table 4, whereas the species-specific resistance profiles are detailed in Table 5. Notable variations in resistance profiles were evident. Among C. upsaliensis isolates (n = 30), high resistance was observed to amoxicillin (93.33%), ampicillin (86.66%), tetracycline (80%), erythromycin (73.33%), and sulfonamides (60%). Similarly, C. jejuni strains (n = 16) exhibited resistance to amoxicillin (87.5%), ampicillin (75%), tetracycline (50%), and erythromycin (43.75%). C. coli isolates (n = 7) showed substantial resistance to amoxicillin (85.71%), ampicillin (71.42%), and tetracycline (57.14%). In contrast, resistance to nalidixic acid, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol remained low across both C. jejuni and C. coli isolates.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter spp. isolated from cats in Kelantan, Malaysia.

Table 3.

Prevalence of resistance to at least one antimicrobial among Campylobacter spp. isolates from cats and its association with host-related risk factors.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial resistance profile of Campylobacter spp. isolates (n = 53).

Table 5.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Campylobacter species isolated from cats in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia.

3.3. Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance Indices of Campylobacter spp. from Cats

The extent of antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter isolates was further quantified using the Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index, calculated for each isolate as MAR = a/b, where a represents the number of antibiotics to which the isolate was resistant, and b denotes the total number of antibiotics tested, as per established methodology [37]. All 53 Campylobacter isolates obtained from feline rectal swabs exhibited MAR indices greater than 0.2, indicating significant antimicrobial pressure and widespread multidrug resistance.

A total of 26 distinct multidrug resistance (MDR) profiles were identified across the 12 antibiotics evaluated, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of resistance among the isolates. The most prevalent MDR pattern involved resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and sulfonamides observed in five isolates (14.70%) for C. upsaliensis (Table 6). This was followed by amoxicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, sulfonamides, and trimethoprim, observed in three isolates (8.82%) for C. jejuni (Table 7). Followed by a third MDR pattern involving resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline observed in two isolates (5.88%) for C. coli (Table 8).

Table 6.

MAR indices and Patterns of antimicrobial resistance phenotypes observed in MDR Campylobacter upsaliensis from cats in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia (n = 34).

Table 7.

MAR indices and Patterns of antimicrobial resistance phenotypes observed in MDR Campylobacter jejuni from cats in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia (n = 34).

Table 8.

MAR indices and Patterns of antimicrobial resistance phenotypes observed in MDR Campylobacter coli from cats in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia (n = 34).

4. Discussion

The detection of Campylobacter spp. in domestic cats carries important public health implications, particularly due to the close human–animal interface and the zoonotic potential of several Campylobacter species [14,38]. Identifying these bacteria in pets offers critical epidemiological insights and informs risk assessment strategies for zoonotic transmission. In the present study, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to provide comprehensive insights into the occurrence, antimicrobial resistance patterns, and risk factors associated with Campylobacter spp. among domestic cats in Kelantan, Malaysia. In the present study, Campylobacter spp. were detected in 35.33% of feline samples. This prevalence aligns closely with previous findings reported in Malaysia, notably by Goni et al. (2017), who observed a similar rate of 32.6% in domestic cats [20]. The marginally higher detection rate in the current study may be influenced by factors such as diagnostic sensitivity, host population characteristics, or localized ecological dynamics that affect pathogen distribution and transmission [39]. On a global scale, research conducted in China by Zhang et al. (2023) [30] reported a Campylobacter spp. prevalence of 30.1% in feline populations. This figure is marginally lower than those reported in Malaysian studies, which may be attributed to variations in ecological settings, husbandry systems, and the diagnostic tools employed across regions. The higher detection rate observed in this study may reflect improved molecular diagnostics, environmental exposure differences, or regional variations in antimicrobial use and pet management practices. The results emphasize the critical need for sustained epidemiological surveillance, the establishment of standardized and validated diagnostic protocols, and the promotion of targeted public health education aimed at reducing the zoonotic risks associated with close human–animal interactions, particularly involving companion animals.

In the present study, Among the Campylobacter species identified, C. upsaliensis was the most prevalent (33.3%), followed by C. jejuni (17.7%) and C. coli (7.8%). These findings support growing recognition of C. upsaliensis as a dominant species in feline hosts, despite historically being underrepresented in public health discussions due to its fastidious growth requirements and diagnostic challenges [40]. Campylobacter upsaliensis was the most frequently isolated species in this study, with a prevalence of 33.3% This aligns with findings by (Goni et al., 2017) [20] who reported C. upsaliensis as a common isolate in cats, often associated with asymptomatic carriage. The predominance of C. upsaliensis in cats may be explained by several factors: first, its strong host adaptation to the feline gastrointestinal tract facilitates efficient colonization and persistence. Second, asymptomatic carriage allows prolonged shedding without clinical signs, supporting silent transmission within domestic and semi-roaming populations. Third, its fastidious growth requirements and poor recovery on conventional culture media have historically led to underestimation, with PCR-based molecular methods now revealing its true epidemiological burden Finally, environmental and behavioral factors, particularly the semi-roaming lifestyle of cats in Kelantan, increase exposure to contaminated environments and prey species that may harbor C. upsaliensis [41]. C. jejuni and C. coli were detected at rates of 17.7% and 7.8%, respectively, comparable to the 15% and 10% reported by the same study. These discrepancies may stem from a range of influencing factors, including divergence in laboratory detection techniques, the occurrence of asymptomatic carriage, seasonal fluctuations in pathogen transmission, variations in host health status, and differential environmental exposure risks across study populations [42].

This study assessed the occurrence and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles of Campylobacter isolates recovered from feline samples in Kelantan, Malaysia [43]. The resistance patterns observed correspond to antimicrobials commonly utilized in small animal veterinary practice. Notably, a high proportion of isolates exhibited resistance to amoxicillin (90.56%), ampicillin (81.13%), tetracycline (67.92%), erythromycin (62.26%), and sulfonamides (54.71%). These results mirror trends reported in both national and international research, highlighting increasing resistance among Campylobacter spp. particularly to macrolides, β-lactams, and tetracyclines, antibiotic classes frequently used in veterinary medicine [44]. Such differences may result from variations in antimicrobial administration protocols, levels of environmental contamination, and the effectiveness of animal health and husbandry practices [28]. Lower resistance was observed for ciprofloxacin (9.43%), kanamycin (1.89%), and chloramphenicol (1.86%), which may reflect restricted or regulated use of these agents in companion animal care [45]. These results point to rising antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. from companion animals, indicating the need for ongoing surveillance, judicious antimicrobial use, and region-specific research [13,46]. A key methodological limitation of this study is the use of the disk diffusion method instead of E-test or broth microdilution MICs, which represent the gold standard for Campylobacter susceptibility testing. This choice was driven by resource constraints and laboratory capacity in our setting. Although disk diffusion remains commonly employed in low- and middle-income countries and provides useful preliminary resistance profiles, it may either underestimate or overestimate true resistance levels. Accordingly, future investigations in Malaysia should incorporate MIC-based methods to ensure more accurate characterization of antimicrobial resistance.

Multidrug resistance (MDR), defined as resistance to ≥3 antimicrobial classes, was detected in 67.92% of isolates, underscoring the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. from companion animals. Notably, 26 distinct MDR phenotypes were documented, with the most common involving resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and sulfonamides. These resistance patterns are reflective of commonly administered antibiotics in routine veterinary care, and mirror findings from previous studies in canine and avian Campylobacter populations [35]. The observed heterogeneity of resistance profiles may be influenced by factors such as antibiotic selection pressure, horizontal gene transfer, and environmental contamination [13,47]. The Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index serves as an effective indicator for evaluating potential exposure risks linked to bacterial sources [48]. In this study, all Campylobacter isolates displayed MAR values between 0.3 and 0.9, exceeding the standard threshold of 0.2, indicating high-risk contamination sources such as environments and substantial antimicrobial pressure within the feline host population.

These findings suggest a substantial level of antimicrobial exposure and a high prevalence of multidrug resistance (MDR), raising concerns about potential overuse or inappropriate antibiotic administration in companion animals [48]. 26 distinct multidrug resistance (MDR) profiles were identified across the 12 antibiotics evaluated, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of resistance among the isolates. The most prevalent MDR pattern involved resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and sulfonamides observed in five isolates of C. upsaliensis. This was followed by amoxicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, sulfonamides, and trimethoprim observed in three isolates of C. jejuni. The third most frequent resistance pattern, involving resistance to amoxicillin, ampicillin, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline observed in two isolates of C. coli, reinforcing the hypothesis of selective pressure driven by veterinary antimicrobial use [22,49]. These findings are consistent with prior reports that link elevated MAR indices to MDR carriage in Campylobacter spp. from various animal reservoirs, including poultry and dogs [48,49,50].

The high MAR indices and varied resistance profiles observed in this study indicate the potential for zoonotic transmission of resistant Campylobacter strains. Particularly concerning are the high resistance levels to first-line antibiotics such as tetracyclines, macrolides, and β-lactams, indicating the urgent need for strengthened antimicrobial stewardship in Malaysia. From a One Health perspective, the detection of multidrug-resistant Campylobacter spp. in cats highlights their role as potential reservoirs for zoonotic transmission [21,50]. Recent molecular studies reporting genomic similarities between human and companion animal isolates further suggest possible bidirectional transmission routes [49,50]. In the Malaysian context, these findings call for concrete measures such as: (i) the establishment of a national surveillance system for AMR in companion animals alongside existing livestock and human programs, (ii) the introduction and enforcement of stricter veterinary prescription policies to prevent over-the-counter access and misuse of antimicrobials, and (iii) community-level awareness campaigns to promote responsible pet ownership, improved hygiene, and prudent antibiotic use. Without such targeted interventions, multidrug-resistant Campylobacter strains may increasingly circulate between animals and humans, amplifying the public health burden. Nevertheless, the interpretation of these findings should consider two key limitations. First, the reliance on convenience sampling may not fully represent the broader cat population in Kelantan, potentially introducing selection bias and limiting generalizability. Second, while phenotypic resistance profiles were established, the absence of molecular characterization of resistance genes restricts deeper insight into the genetic mechanisms underlying multidrug resistance and their potential for horizontal transfer. Addressing these limitations in future studies through representative sampling and molecular AMR gene profiling will strengthen the evidence base for intervention. Without such targeted efforts, multidrug-resistant Campylobacter strains may increasingly circulate between animals and humans, amplifying the public health burden.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a high prevalence of Campylobacter spp., including multidrug-resistant strains, among domestic cats in Kelantan, Malaysia. The detection of diverse resistance profiles and elevated MAR indices underscores the role of cats as potential reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the region. These findings call for the establishment of regional surveillance systems for companion animals and the implementation of judicious veterinary antibiotic use as part of an integrated One Health approach. Explicit recognition of the limitations of this study is important: its cross-sectional design restricts the ability to assess temporal trends; the use of disk diffusion rather than MIC-based methods may have led to under- or overestimation of resistance; and reliance on convenience sampling limits the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, the exclusive focus on Campylobacter spp. did not account for potential co-infections with other zoonotic pathogens. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to monitor shedding dynamics, incorporate molecular characterization of resistance genes, and expand surveillance to include co-occurring pathogens. Such efforts will strengthen the evidence base needed to guide AMR mitigation strategies in Malaysia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.F., M.D.G. and N.F.K.; methodology, C.A.F., M.D.G., M.S.G. and A.Y.; software, C.A.F. and H.A.A.; formal analysis, C.A.F., H.A.A. and M.S.G.; investigation, C.A.F., M.D.G., M.S.G. and A.Y.; resources, M.D.G. and N.F.K.; data curation, C.A.F., S.I.S. and H.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.S. and C.A.F.; writing—review and editing, C.A.F., M.D.G., S.I.S., N.F.K., H.A.A. and M.S.G.; supervision, M.D.G. and N.F.K.; project administration, M.D.G. and N.F.K.; funding acquisition, M.D.G. and N.F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, grant number R/FUND/A0600/01871A/001/2022/01099.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving animals in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, in accordance with national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Approval Code: UMK/FPV/ACUE/PG/002/2023; Approval Date: 12 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, for providing financial and institutional support for this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thépault, A.; Rose, V.; Queguiner, M.; Chemaly, M.; Rivoal, K. Dogs and Cats: Reservoirs for Highly Diverse Campylobacter jejuni and a Potential Source of Human Exposure. Animals 2020, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, G.; Wang, H.; Yu, M.; He, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, M. Prevalence, Genomic Characterization and Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter spp. Isolates in Pets in Shenzhen, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1152719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.O.; Ameh, J.A.; Abubakar, M.B.; Ibrahim, A.Y.; Musa, H.K.; Usman, S.Y.; Bello, R.M. Campylobacteriosis in Africa: ANeglected Demon. Microbe 2025, 7, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, P.; Dodi, I. Campylobacter jejuni/coli Infection: Is It Still a Concern? Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, K.; Brown, J.A.; Lipton, B.; Dunn, J.; Stanek, D.; Barton Behravesh, C.; Chapman, H.; Conger, T.H.; Vanover, T.; Edling, T.; et al. A Review of Zoonotic Disease Threats to Pet Owners: A Compendium of Measures to Prevent Zoonotic Diseases Associated with Non-Traditional Pets: Rodents and Other Small Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians, Backyard Poultry, and Other Selected Animals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022, 22, 303–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Chies, J.A.B. Zoonotic Spillover: Understanding Basic Aspects for Better Prevention. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2021, 44, e20200355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella, V.; Wongnak, P.; Tsai, Y.L.; Nguyen, V.L.; Tan, D.Y.; Tong, K.B.; Halos, L. Human Social Conditions Predict the Risk of Exposure to Zoonotic Parasites in Companion Animals in East and Southeast Asia. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enany, S.; Piccirillo, A.; Elhadidy, M.; Tryjanowski, P. The Role of Environmental Reservoirs in Campylobacter-Mediated Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 773436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwobodo, D.C.; Ugwu, M.C.; Anie, C.O.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Ikem, J.C.; Uchenna, V.C.; Saki, M. Antibiotic Resistance: The Challenges and Some Emerging Strategies for Tackling a Global Menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endale, H.; Mathewos, M.; Abdeta, D. Potential Causes of Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance and Preventive Measures in One Health Perspective—A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 7515–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, B.; Xia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, M.; Cheng, Z.; Lv, C.; Chen, W.; et al. Companion Animals as Sources of Hazardous Critically Important Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli: Genomic Surveillance in Shanghai. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y. One Health Strategies in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance: A Southeast Asian Perspective. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 03025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltramo, B.; Kolluru, S.; Slager, L.; Wall, L.; Ostwald, K.; Rasali, D. Comparative Analysis of One Health Policies in Asia for Exploring Opportunities for British Columbia in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial Resistance: One Health Approach. Vet. World 2022, 15, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwakoya, O.M.; Okoh, A.I. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Campylobacter Species in Wastewater Effluents: A Menace of Environmental and Public Health Concern. Helicobacter 2024, 29, e13095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, S.M.I.; Mokhtar, M.I.; Arham, A.F. Public Perspectives on Strays and Companion Animal Management in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, T.S.M.; Panting, A.J.; Johari, M.Z.; Perialathan, K.; Ahmad, M.; Sanusi, N.H.A. Dog Ownership: Licensing and Vaccination—NHMS 2020 Findings. Inst. Health Behav. Res. 2023, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Goni, M.D.; Abdul-Aziz, S.; Dhaliwal, G.K.; Zunita, Z.; Bitrus, A.A.; Abbas, M.A. Occurrence of Campylobacter in Dogs and Cats in Selangor, Malaysia and the Associated Risk Factors. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2017, 13, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Goni, M.D.; Osman, A.Y.; Abdul-Aziz, S.; Zunita, Z.; Dhaliwal, G.K.; Jalo, M.I.; Bitrus, A.A.; Jajere, S.M.; Abbas, M.A. Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter spp. and Arcobacter butzleri from Pets in Malaysia. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2018, 13, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunović, K.; Zajkoska, S.; Bezek, K.; Klančnik, A.; Barlič Maganja, D.; Smole Možina, S. Comparison of Campylobacter jejuni Slaughterhouse and Surface-Water Isolates Indicates Better Adaptation of Slaughterhouse Isolates to the Chicken Host Environment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stef, L.; Cean, A.; Vasile, A.; Julean, C.; Drinceanu, D.; Corcionivoschi, N. Virulence Characteristics of Five New Campylobacter jejuni Chicken Isolates. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, M.; Refrégier-Petton, J.; Laisney, M.J.; Ermel, G.; Salvat, G. Campylobacter Contamination in French Chicken Production from Farm to Consumers. Use of a PCR Assay for Detection and Identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.J.; Qiao, B.; Xu, X.B.; Zhang, J.Z. Development and Application of a Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Method for Campylobacter jejuni Detection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 3090–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Clark, C.G.; Taylor, T.M.; Pucknell, C.; Barton, C.; Price, L.; Woodward, D.L.; Rodgers, F.G. Colony Multiplex PCR Assay for Identification and Differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4744–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc-Maridor, M.; Beaudeau, F.; Seegers, H.; Denis, M.; Belloc, C. Rapid Identification and Quantification of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni by Real-Time PCR in Pure Cultures and in Complex Samples. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klena, J.D.; Parker, C.T.; Knibb, K.; Ibbitt, J.C.; Devane, P.M.L.; Horn, S.T.; Miller, W.G.; Konkel, M.E. Differentiation of Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter lari, and Campylobacter upsaliensis by a Multiplex PCR Developed from the Nucleotide Sequence of the Lipid A Gene lpxA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 5549–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddafi, M.S.; Yakubu, Y.; Bello, M.B.; Bitrus, A.A.; Musawa, A.I.; Garba, B. Occurrence and Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Layer Chickens in Kebbi, Nigeria. Folia Vet. 2022, 66, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, B.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y. Occurrence and Risk Levels of Antibiotic Pollution in the Coastal Waters of Eastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 71371–71381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titilawo, Y.; Sibanda, T.; Obi, L.; Okoh, A.I. Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Indexing of Escherichia coli to Identify High-Risk Sources of Faecal Contamination of Water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10969–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeze, C.F.; Goni, M.D.; Kamaruzzaman, F.; Sani, G.M.; Yakubu, A. Exploring Campylobacter jejuni: Elucidating Pathogenic Mechanisms, Virulence Factors, Antimicrobial Resistance in Diverse Animal Species. Vet. Integr. Sci. 2025, 23, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulli, M.C.; Galli, N.; John, R.S.; Muylaert, R.L.; Santini, M.; Hayman, D.T.S. Land Use Change and Infectious Disease Emergence. Rev. Geophys. 2025, 63, e2022RG000785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanić, K.; Acke, E.; Roe, W.D.; Marshall, J.C.; Cornelius, A.J.; Biggs, P.J.; Midwinter, A.C. Comparison of the Pathogenic Potential of Campylobacter jejuni, C. upsaliensis and C. helveticus and Limitations of Using Larvae of Galleria mellonella as an Infection Model. Pathogens 2020, 9, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddafi, M.S.; Yakubu, Y.; Usman Junaidu, A.; Bello, M.B.; Bitrus, A.A.; Musawa, A.I.; Garba, B.; Lawal, H. Occurrence of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) From Dairy Cows in Kebbi, Nigeria. Iran. J. Vet. Med. 2022, 17, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, C.M.; Quiñones, R.A.; Echeverría, C.A.; Tarazona, J. Environmental and Ecological Factors Mediate Taxonomic Composition and Body Size of Polyplacophoran Assemblages along the Peruvian Province. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M.; Sahin, O.; Adiguzel, M.C. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Campylobacter Species in Shelter-Housed Healthy and Diarrheic Cats and Dogs in Turkey. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haulisah, N.A.; Hassan, L.; Jajere, S.M.; Ahmad, N.I.; Bejo, S.K. High Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Multidrug Resistance among Bacterial Isolates from Diseased Pets: Retrospective Laboratory Data (2015–2017). PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneschi, A.; Bardhi, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A. The Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Veterinary Medicine, a Complex Phenomenon: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulu, W.; Joossens, M.; Kibret, M.; Van den Abeele, A.M.; Houf, K. Campylobacter Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile in under Five-Year-Old Diarrheal Children, Backyard Farm Animals, and Companion Pets. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, N.; Islam, N.F.; Sonowal, S.; Prasad, R.; Sarma, H. Environmental Antibiotics and Resistance Genes as Emerging Contaminants: Methods of Detection and Bioremediation. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtula, V.; Jackson, C.R.; Farrell, E.G.; Barrett, J.B.; Hiott, L.M.; Chambers, P.A. Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococcus spp. Isolated from Environmental Samples in an Area of Intensive Poultry Production. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buranasinsup, S.; Wiratsudakul, A.; Chantong, B.; Maklon, K.; Suwanpakdee, S.; Jiemtaweeboon, S.; Sakcamduang, W. Prevalence and Characterization of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Veterinary Staff, Pets, and Pet Owners in Thailand. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16 (Suppl. S1), 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Beyi, A.F.; Yin, Y. Zoonotic and Antibiotic-Resistant Campylobacter: A View through the One Health Lens. One Health Adv. 2023, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, Z.M.; Alhatami, A.O.; Ismail Khudhair, Y.; Muhsen Abdulwahab, H. Antibiotic Resistance Profile and Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Index of Campylobacter Species Isolated from Poultry. Arch. Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Kadri, S.S. Key Takeaways from the US CDC’s 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report for Frontline Providers. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premarathne, J.M.K.J.K.; Anuar, A.S.; Thung, T.Y.; Satharasinghe, D.A.; Jambari, N.N.; Abdul-Mutalib, N.A.; Huat, J.T.Y.; Basri, D.F.; Rukayadi, Y.; Nakaguchi, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance against Tetracycline in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli in Cattle and Beef Meat from Selangor, Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnecke, A.L.; Schwarz, S.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Jensen, K.C.; Bahramsoltani, M. A Survey on Companion Animal Owners’ Perception of Veterinarians’ Communication about Zoonoses and Antimicrobial Resistance in Germany. Animals 2024, 14, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.L.; Liao, Y.S.; Chen, B.H.; Teng, R.H.; Wang, Y.W.; Chang, J.H.; Chiou, C.S. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Relatedness among Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni from Humans and Retail Chicken Meat in Taiwan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 38, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnússon, S.H.; Guðmundsdóttir, S.; Reynisson, E.; Rúnarsson, A.R.; Harðardóttir, H.; Gunnarson, E.; Georgsson, F.; Reiersen, J.; Marteinsson, V.T.H. Comparison of Campylobacter jejuni Isolates from Human, Food, Veterinary and Environmental Sources in Iceland Using PFGE, MLST and fla-SVR Sequencing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).