Abstract

This research compares the Mediterranean and Japanese diets and considers diet as associated with anti-ageing as well as leading a long and healthy life. Since Mediterranean countries, including Italy and Greece, have one-third the mortality ratio with respect to cardiovascular diseases compared to America and northern Europe, the Mediterranean diet is regarded as healthy. Here, the research shows the reasons why Mediterranean and Japanese diets have these properties. Both the Mediterranean and Japanese diets are typically low in fat, sugar, and calories, and are characterised by a high intake of vegetables, legumes, fish, and cereals. Differences include a greater consumption of polyphenol-rich extra virgin olive oil, dairy products, and a lower amount of meat consumption in the Mediterranean diet, as well as less use of fat; there is an abundant consumption of fermented foods and seaweed in the Japanese diet. Japan’s globally leading long life expectancy is partly attributed to the cultural concept of “ME-BYO,” which emphasises recognising and managing non-disease conditions before they develop into clinical illness. This tendency may be one of the reasons for the long lifespan of Japanese people.

1. Introduction

The Mediterranean diet has been focused on as a health-beneficial diet since a survey was conducted in the United States in the 1950s. At that time, increasing numbers of people in America suffered from lifestyle-related diseases, and researchers on dietary intervention in the world noticed that the Mediterranean diet is a healthy choice [1,2,3].

According to the research, the death ratio from cardiovascular diseases in the Mediterranean region is less than one-third when compared to the U. S. and northern Europe. Therefore, the Mediterranean diet has been considered healthy and facilitates longevity [4,5].

On the other hand, the Japanese diet is also regarded as healthy because Japanese people have held the longest life expectancy record worldwide for over 20 years. In addition, Japanese people perceive that “medicine and food have the same root,” meaning daily intake of well-balanced, delicious, and healthy meals prevents and cures illness. However, compared to the Mediterranean diet, the effectiveness of the Japanese diet for health has not been confirmed by scientific research yet, since only a few research studies were conducted [6,7]. Furthermore, shortly after World War II, Japan had a high incidence of stroke because of the high salt, low protein, and increased intake of high carbohydrates. It is unsurprising that Japan has recently become one of the leading countries in healthy longevity. Today, the Mediterranean diet has been listed as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO along with the Japanese diet.

This systematic review explores the similarities and differences between Mediterranean and Japanese diets, which are both considered healthy. Furthermore, this research indicates that the Mediterranean-styled Japanese diet is useful for healthy longevity and for resolving ME-BYO conditions.

2. Methods

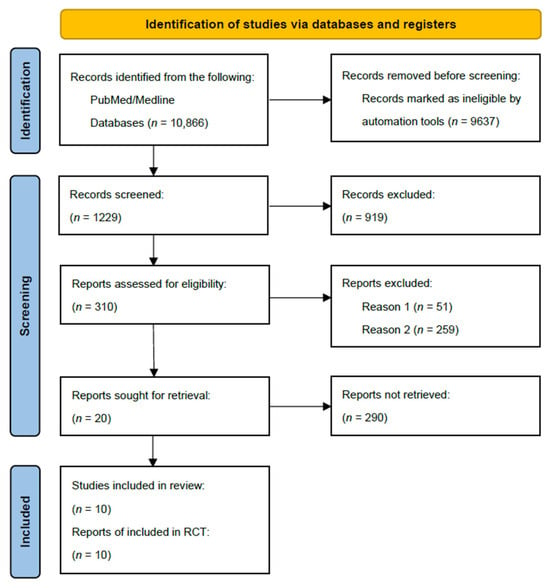

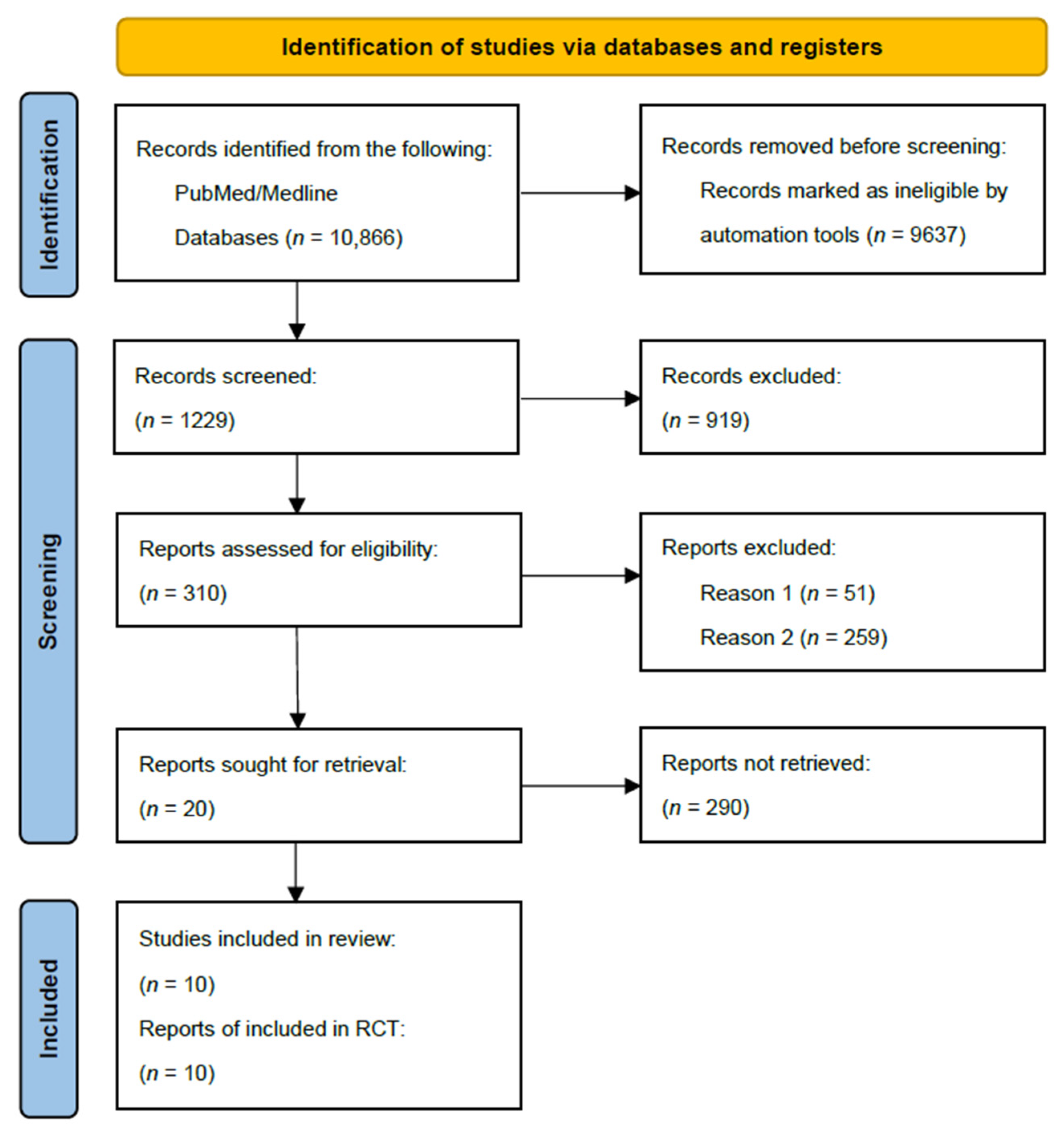

This research follows the Cochrane guidelines and uses Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [8]. This systematic review conducted two separate analyses for Mediterranean and Japanese diets. (a) Search strings were “Mediterranean diet” and “Japanese diet”, and these keywords were searched in “PubMed”. (b) The time frame was “1 year” in the Mediterranean diet and “10 years” in the Japanese diet. (c) The selection process (screening, eligibility, and inclusion) of each diet is shown in the subsections below. (d) Tools for assessing study quality were not used in the systematic review.

2.1. Article Selection Process of the Mediterranean Diet

Regarding the Mediterranean diet, a PubMed keyword search of “Mediterranean diet” showed 10,866 articles. After limiting the publication period to the past “1 year”, 1229 articles remained. Excluding papers without “abstracts” or “free full text” access reduced the number to 903. There were 259 articles with the article type “Review”, and 51 articles in “Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT)”. The sum of “Review” and “RCT” article types was 310. Since the systematic review displayed the top 10 “Best match” articles of “Review” and “RCT”, a total of 20 articles were displayed, and the other 290 articles were excluded. (as of 2 of September 2025). The PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review for the Mediterranean diet is shown in Figure 1.

2.2. Article Selection Process of the Japanese Diet

As well as the Mediterranean diet, a PubMed keyword search of “Japanese diet” showed 309 articles. Since articles published regarding “Japanese diet” were not so many, the publication period was limited to the past “10 years” and 175 articles remained. There were 17 articles with the article type “Review”, and 10 articles in “Clinical Trial” and/or “Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT)”. The sum of “Review” and “Clinical Trial” and/or “RCT” article types was 27. Since the systematic review displayed the top 10 “Best match” articles of “Review” and “Clinical Trial” and/or “RCT”, a total 20 articles were displayed, and other 7 articles were excluded. (as of 2 of September 2025).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review: the Mediterranean diet.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review: the Mediterranean diet.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Scientific Evidence Regarding the Mediterranean Diet

3.1.1. Mediterranean Diet-Associated “Review Articles” Within 1 Year (Top 10)

As shown in the flowchart above, a PubMed search with the keyword “Mediterranean diet” yielded 10,866 articles. There were 259 “Review” articles within 1 year, and the top 10 articles shown in the filter “Best match” with appropriate data are summarised in Table 1 [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Table 1.

Mediterranean diet associated “review articles” within 1 year (Best match: top 10).

3.1.2. Mediterranean Diet-Associated “Randomised Clinical Trials” in Past 1 Year (Top 10)

As well as review articles, there were 51 “randomised clinical trials (RCT)” within 1 year, and the top 10 articles shown in the filter “Best match” with appropriate data were summarised in Table 2 [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Table 2.

Mediterranean diet-associated “randomised clinical trials (RCT)” in past 1 year (Best match: top 10).

3.2. Summary of Scientific Evidence Regarding the Japanese Diet

3.2.1. Japanese Diet-Associated “Review Articles” in Past 10 Years (Top 10)

As well as the Mediterranean diet, a PubMed search with the keyword “Japanese diet” yielded 309 articles. There were 17 “Review” articles within 1 year, and the top 10 articles shown in the filter “Best match” with appropriate data are summarised in Table 3 [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. With even fewer articles than the Mediterranean diet, an increasing number of articles have reported the health benefits of the Japanese diet.

Table 3.

Japanese diet-associated “review articles” in past 10 years (Best match: top 10).

3.2.2. Japanese Diet-Associated “Randomised Clinical Trials (RCT)” and/or “Clinical Trials” in Past 10 Years (Top 10)

In addition to review articles, 10 articles filtered with “Clinical Trial” and/or “RCT” in “Japanese diet” are summarised in Table 4 [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Table 4.

Japanese diet associated “Clinical Trian” and/or “randomised clinical trials (RCT)” in past 10 years (Best match top 10).

4. Discussion

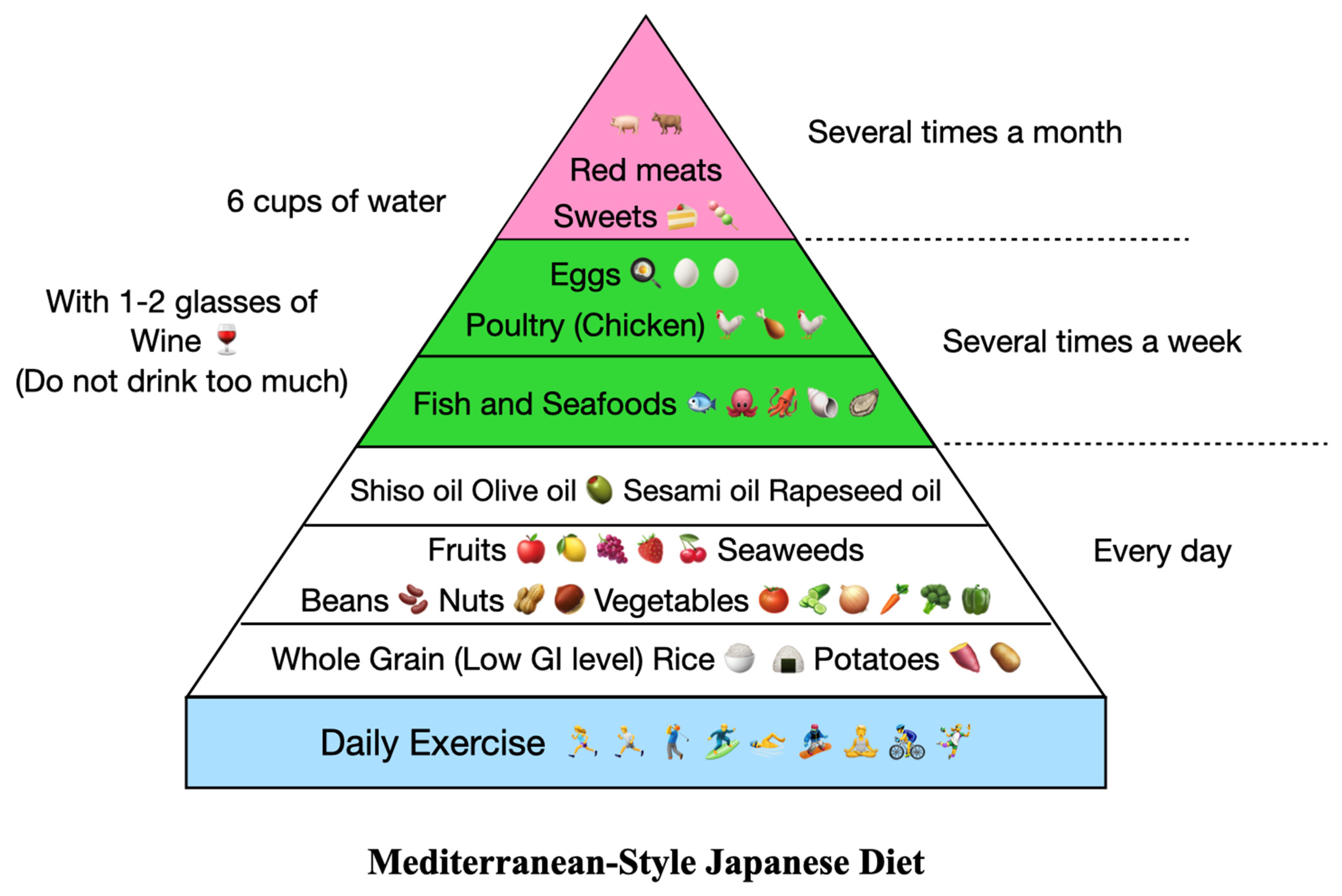

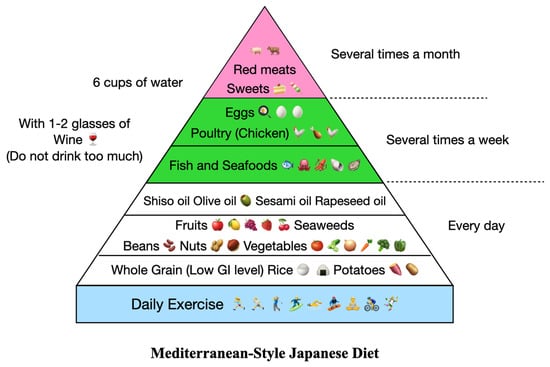

Figure 2 shows the Mediterranean-style Japanese diet pyramid. Characteristic features of the Mediterranean and Japanese diets are the high consumption of plant-based foods such as vegetables, legumes, and grains, as well as seafood [31]. The Mediterranean diet extensively uses extra virgin olive oil and dairy products, but consumes a limited amount of red meat. On the other hand, the Japanese diet avoids using animal fats by making better use of “umami” (e.g., glutamic acid), which is rich in fermented foods, consuming lots of seaweeds, and is low in calories, and incorporates fresh, seasonal ingredients. Until the middle of the 19th century, Japanese people rarely ate meat. Saturated fatty acids found in red meat increase LDL and triglycerides, induce insulin resistance, and cause the onset of cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, excessive consumption of red meat is not recommended [49]. Instead, legumes are high in protein and low in fat. Fermented foods such as natto, soy sauce, miso, pickles, and bonito flakes are the components of a healthy Japanese diet. In addition, the consumption of yoghurt and cheese, common in the Mediterranean diet, is increasing in Japan. The Mediterranean diet has been an attractive dietary choice because this diet reduces the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases. The interest in a healthy diet with large consumption of vegetables and fruits is increasing worldwide. For example, the Five-a-Day campaign in the U. S. encourages people to consume 400 g of five different types of vegetables per day [50], and interest in vegetarianism is also increasing.

Figure 2.

Mediterranean-style Japanese diet pyramid: A diet that prevents ME-BYO (non-disease condition) and is more suited to a healthy, long life.

The randomised clinical trials (RCTs) of the Mediterranean diet and the clinical trial or RCT of the Japanese diet revealed the benefit of these dietary regimes. The Mediterranean diet indicated the improvement of the symptoms of metabolic disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases [19], enteritis [20], depression [22], atherosclerosis [23], and metabolic syndrome [24]. The improvement of dyslipidemia by the red and processed meat-excluded Mediterranean diet has also been reported [28]. As well as the Mediterranean diet, the Japanese diet also improves the symptoms of metabolic disorders [40,41,44,45]. In addition, a report indicated the improvement of gut microbiota conditions [39], and the other report showed the benefit of the consumption of water-soluble dietary fibres in seaweeds [47]. Furthermore, there was an article that improves the quality of sleep by the consumption of white rice, which is the staple of the Japanese diet [42]. Since both the Mediterranean and Japanese diets are typically low in fat, sugar, and calories, and are characterised by a high intake of vegetables, legumes, fish, and cereals, it is biologically plausible to improve the metabolic disorders. Usually, the risk of metabolic disorders is increased by the consumption of a typical Western diet with high fat and sugar content and high calories.

Recently, attention has been focused on phytochemicals [51]. These are found in a variety of vegetables and fruits, including onions, oranges, green tea, soybeans, and grapes, which are particularly rich in polyphenols. Fermented grape foods from Koshu, a Japanese grape strain (K-FGF), consisting of the grape skin and seed paste of Vitis vinifera Koshu, were fermented with plant lactic acid bacteria. K-FGF contains a large amount of quercetin and suppresses disorders related to chronic inflammation through the suppression of TNF-α [52]. The anti-inflammatory properties of phytochemicals reduce the risk of lifestyle-related diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, pulmonary diseases and dysbiosis-associated intestinal diseases [53]. They are also expected to suppress sepsis, which is more likely to manifest in a chronic inflammatory condition [54].

Prebiotics, probiotics, phytochemicals, and vitamin D are referred to as the 3PDs. Recently, the importance of vitamin D has been re-evaluated: it affects butyrate-producing bacteria to help upregulate immune responses by the activation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and enhances antimicrobial peptides to improve the gut microbiome [55]. The gut microbiota has a characteristic feature of obese and lean individuals. Individuals with obesity tend to have Firmicutes-dominant and lean individuals tend to have Bacteroidetes-dominant gut microbiota. A lower F/B ratio is considered healthy. Good gut microbiota is raised on a diet rich in Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MAC) [56], and seaweed, a common component of the Japanese diet, and rich in high-quality water-soluble dietary fibre.

Japanese people tend to have meals approximately 80% full and avoid overeating. The calorie restriction activates the sirtuin genes that keep cells younger [57] and suppress dementia, fatty liver, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions [58].

Ironically, a limitation of the study is that the adaptation of Western-style lifestyles in Japan diminishes these healthy dietary practices. A typical example is in Okinawa. Okinawans once ate a healthy diet that mainly consisted of vegetables, with a little fish and occasional consumption of meat, such as pork. The lifestyle led to a very low incidence of diseases and a high number of centenarians, making the Okinawan lifestyle a global phenomenon [59]. However, the dietary habits of younger generations in Okinawa have rapidly Americanised, leading to health problems such as increasing obesity, like those of the average Americans, and efforts to correct these issues are needed [60]. Meanwhile, other dietary approaches incorporating the benefits of the Mediterranean diet, such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet, have become increasingly popular in the U. S. and other places [61].

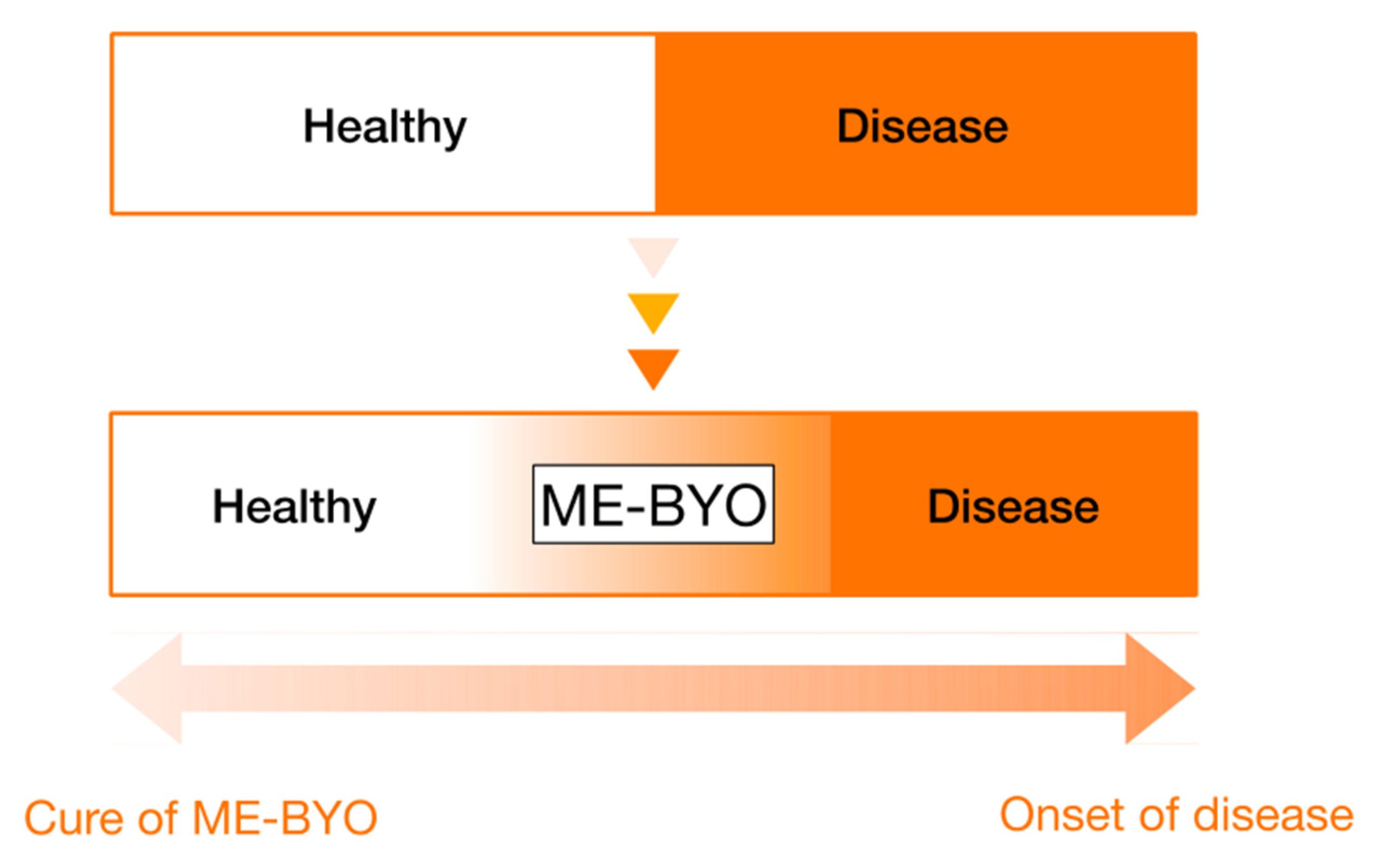

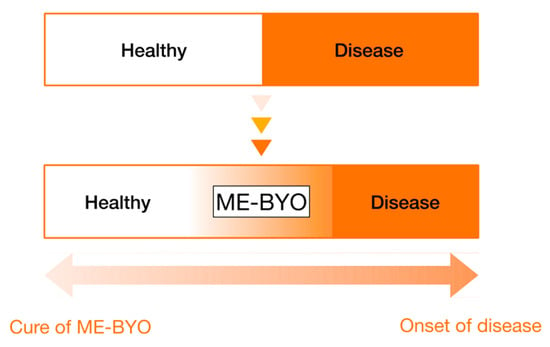

The idea of “Medicine and Food have the Same Root” is deeply rooted in Japan, where eating a nutritionally balanced diet every day prevents and cures a variety of diseases. Furthermore, traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo) includes the concept of “Yakuzen”, eating a diet tailored to symptoms and the body’s condition [62]. This demonstrates how important “what we eat” is to maintaining a healthy condition. The idea of finding and treating “ME-BYO” (non-disease condition) is widely spread in Japan (Figure 3). Eating a daily balanced diet helps prevent “ME-BYO” and maintains good health, making it important for a healthy, long life. The Mediterranean-style Japanese diet is effective for the anti-ageing effects and is also recommended for the prevention of “ME-BYO”.

Figure 3.

Schematic view of ME-BYO. We cannot distinguish between a healthy state and a diseased state. ME-BYO (non-disease state) is the state that continuously changes from a healthy state to a diseased one. Generally, ME-BYO is a state in which there are no subjective symptoms but abnormalities in examinations, or a state in which there are subjective symptoms, but no abnormalities in examinations. The importance of ME-BYO has been increasing because the prevention of ME-BYO in the younger generation will reduce medical expenses and prolong healthy longevity.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Mediterranean-style Japanese diet, a well-balanced diet, reduces the risk of a variety of diseases by preventing the onset of chronic inflammation. In recent years, there has been increasing evidence that the benefits of the Mediterranean and Japanese diets have been lost because of the westernisation of diets. On the other hand, however, with the increasing consciousness of healthy lifestyles, the number of new dietary methods that incorporate the benefits of the Mediterranean diet is reportedly increasing. In this regard, the Mediterranean-style Japanese diet can prevent the manifestation of “ME-BYO” (non-disease condition) and has anti-ageing properties, which might contribute to healthy and long living, not only for Japanese people but also for people around the world. Further research attempts of the dietary intervention are necessary for the healthy longevity and anti-ageing effects in the future.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this paper is available from PubMed or other internet search for free, unless materials are not “free full text” available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declear there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Kiani, A.K.; Medori, M.C.; Bonetti, G.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Stuppia, L.; Connelly, S.T.; Herbst, K.L.; et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E36–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A.; Mienotti, A.; Karvonen, M.J.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Buzina, R.; Djordjevic, B.S.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.; Keys, M.H.; et al. The Diet and 15-Year Death Rate in the Seven Countries Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1986, 124, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushi, L.H.; Lenart, E.B.; Willett, W.C. Health implications of Mediterranean diets in light of contemporary knowledge. 1. Plant foods and dairy products. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1407S–1415S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Sylivris, A.L.; Sualeheen, A.; Scott, D.; Tan, S.-Y.; Villani, A.; Baguley, B.J.; Abbott, G.; Kiss, N.; Daly, R.M.; et al. The effects of Mediterranean diet with and without exercise on body composition in adults with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 51, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Trichopoulou, A.; de la Cruz, J.N.; Cervera, P.; Álvarez, A.G.; La Vecchia, C.; Lemtouni, A.; Trichopoulos, D. Does the definition of the Mediterranean diet need to be updated? Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 927–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, K.; Kumazawa, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Nagaoka, I. The Recommendation of the Mediterranean-styled Japanese Diet for Healthy Longevity. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2024, 24, 1794–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Sasaki, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Okubo, H.; Hosoi, Y.; Horiguchi, H.; Oguma, E.; Kayama, F. Dietary glycemic index and load in relation to metabolic risk factors in Japanese female farmers with traditional dietary habits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Ragusa, F.S.; Dominguez, L.J.; Cusumano, C.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet and osteoarthritis: An update. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Ragusa, F.S.; Petralia, V.; Ciriminna, S.; Di Bella, G.; Schirò, P.; Sabico, S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet and spirituality/religion: Eating with meaning. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, P.; Girgenti, A.; Buttacavoli, M.; Nuzzo, D. Enriching the Mediterranean diet could nourish the brain more effectively. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1489489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Varga, P.; Ungvari, Z.; Fekete, J.T.; Buda, A.; Szappanos, Á.; Lehoczki, A.; Mózes, N.; Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; et al. The role of the Mediterranean diet in reducing the risk of cognitive impairement, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. GeroScience 2025, 47, 3111–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimba, N.R.; Mzimela, N.; Sosibo, A.M.; Khathi, A. Effectiveness of Prebiotics and Mediterranean and Plant-Based Diet on Gut Microbiota and Glycemic Control in Patients with Prediabetes or Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteri, V.; Galeano, F.; Panebianco, S.; Piticchio, T.; Le Moli, R.; Frittitta, L.; Vella, V.; Baratta, R.; Gullo, D.; Frasca, F.; et al. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Sexual Function in People with Metabolic Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furbatto, M.; Lelli, D.; Incalzi, R.A.; Pedone, C. Mediterranean Diet in Older Adults: Cardiovascular Outcomes and Mortality from Observational and Interventional Studies—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, D. The Mediterranean Diet, the DASH Diet, and the MIND Diet in Relation to Sleep Duration and Quality: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Guglielmetti, M.; Ferraris, C.; Frias-Toral, E.; Azpíroz, I.D.; Lipari, V.; Di Mauro, A.; Furnari, F.; Castellano, S.; Galvano, F.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Quality of Life in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleu, S.; Becherucci, G.; Godny, L.; Mentella, M.C.; Petito, V.; Scaldaferri, F. The Key Nutrients in the Mediterranean Diet and Their Effects in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Redondo, J.; Malcampo, M.; Pérez-Vega, K.A.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Pintó, X.; Arós, F.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Modulation of Neuroinflammation-Related Genes in Elderly Adults at High Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, C.; Beke, M.; Nieves, C.; Mai, V.; Stiep, T.; Tholanikunnel, T.; Ramirez-Zamora, A.; Hess, C.W.; Langkamp-Henken, B. Promotion of a Mediterranean Diet Alters Constipation Symptoms and Fecal Calprotectin in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, M.; Piticchio, T.; Alibrandi, A.; Le Moli, R.; Pallotti, F.; Campennì, A.; Cannavò, S.; Frasca, F.; Ruggeri, R.M. Effects of Dietary Habits on Markers of Oxidative Stress in Subjects with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Comparison Between the Mediterranean Diet and a Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients 2025, 17, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Suárez, B.M.; Hernández-Fleta, J.L.; Molero, P.; González-Pinto, A.; Lahortiga, F.; Cabrera, C.; Chiclana-Actis, C.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; PREDI-DEP Investigators. Mediterranean diet-based intervention to improve depressive symptoms: Analysis of the PREDIDEP randomized trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 27, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughanem, H.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Larriva, A.P.A.-D.; Romero-Cabrera, J.L.; Gómez-Luna, P.; Martín-Piedra, L.; Rodríguez-Cantalejo, F.; Tinahones, F.J.; Serrano, E.M.Y.; Soehnlein, O.; et al. Mediterranean diet, neutrophil count, and carotid intima-media thickness in secondary prevention: The CORDIOPREV study. Eur. Hear. J. 2024, 46, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Lorente, H.; García-Gavilán, J.F.; Shyam, S.; Konieczna, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Fitó, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Curto, A.; et al. Mediterranean Diet, Physical Activity, and Bone Health in Older Adults: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e253710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Redondo, J.; Hernáez, Á.; Sanllorente, A.; Pintó, X.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Subirana, I.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Modulates Gene Expression of Cholesterol Efflux Receptors in High-Risk Cardiovascular Patients. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaki, A.; Denaro, E.; Crimella, M.; Castellani, R.; Vellvé, K.; Izquierdo, N.; Basso, A.; Paules, C.; Casas, R.; Benitez, L.; et al. Effect of Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction during pregnancy on placental volume and perfusion: A subanalysis of the IMPACT BCN randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 2042–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasti, A.N.; Katsas, K.; Pavlidis, D.E.; Stylianakis, E.; Petsis, K.I.; Lambrinou, S.; Nikolaki, M.D.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Hatziagelaki, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; et al. Clinical Trial: A Mediterranean Low-FODMAP Diet Alleviates Symptoms of Non-Constipation IBS—Randomized Controlled Study and Volatomics Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Alfaro, L.; Jiménez, C.T.; Silveira-Sanguino, V.; Gómez, M.J.N.; Fernández-Moreno, C.; Cuesta, A.M.R.; Arana, A.F.L.; Calvo, Ó.S.; De Haro, I.M.; Aguilera, C.M.; et al. Intervention design and adherence to Mediterranean diet in the Cardiovascular Risk Prevention with a Mediterranean Dietary Pattern Reduced in Saturated Fat (CADIMED) randomized trial. Nutr. Res. 2025, 136, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, S.; Shimazu, T.; Tomata, Y.; Zhang, S.; Abe, S.; Lu, Y.; Tsuji, I. Japanese Diet and Mortality, Disability, and Dementia: Evidence from the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, M.; Watanabe, N.; Suzuki, M.; Kobori, M. Japanese-Style Diet and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Goto, Y.; Ota, H.; Kito, K.; Mano, F.; Joo, E.; Ikeda, K.; Inagaki, N.; Nakayama, T. Characteristics of the Japanese Diet Described in Epidemiologic Publi-cations: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2018, 64, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Fedacko, J.; Fatima, G.; Magomedova, A.; Watanabe, S.; Elkilany, G. Why and How the Indo-Mediterranean Diet May Be Superior to Other Diets: The Role of Antioxidants in the Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, S.; Brasacchio, C.; Pivari, F.; Salzano, C.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. What is the best diet for cardiovascular wellness? A comparison of different nutritional models. Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2020, 10, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Tonchev, A.B.; Pancheva, R.Z.; Yamashima, T.; Venditti, S.; Ferraguti, G.; Terracina, S. Increasing Life Expectancy with Plant Pol-yphenols: Lessons from the Mediterranean and Japanese Diets. Molecules 2025, 30, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Nabavizadeh, F.; Fedacko, J.; Pella, D.; Vanova, N.; Jakabcin, P.; Fatima, G.; Horuichi, R.; Takahashi, T.; Mojto, V.; et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension via Indo-Mediterranean Foods, May Be Superior to DASH Diet Intervention. Nutrients 2022, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Dang, B.N.; Moore, T.B.; Clemens, R.; Pressman, P. A review of nutrition and dietary interventions in oncology. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120926877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugane, S. Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: Insights from a food and nutrition perspective. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 75, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.J.; Muskiet, F.A.J.; Verheesen, R.H.; Schaafsma, G.; Schaafsma, A.; Geurts, J.M.W. Thyroidal and Extrathyroidal Requirements for Iodine and Selenium: A Combined Evolutionary and (Patho)Physiological Approach. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushida, M.; Sugawara, S.; Asano, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Fukuda, S.; Tsuduki, T. Effects of the 1975 Japanese diet on the gut microbiota in younger adults. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, S.; Kushida, M.; Iwagaki, Y.; Asano, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Tomata, Y.; Tsuji, I.; Tsuduki, T. The 1975 Type Japanese Diet Improves Lipid Metabolic Parameters in Younger Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, M.; Kushida, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Tomata, Y.; Tsuji, I.; Tsuduki, T. Abdominal Fat in Individuals with Overweight Reduced by Consumption of a 1975 Japanese Diet: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2019, 27, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, M.; Toyomaki, A.; Kiso, Y.; Kusumi, I. Impact of a Rice-Centered Diet on the Quality of Sleep in Association with Reduced Oxidative Stress: A Randomized, Open, Parallel-Group Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, R.; Sato, W.; Minemoto, K.; Fushiki, T. Hunger promotes the detection of high-fat food. Appetite 2019, 142, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, C.; Shijo, Y.; Kameyama, N.; Umezawa, A.; Sato, A.; Nishitani, A.; Ayaori, M.; Ikewaki, K.; Waki, M.; Teramoto, T. Effects of Nutrition Education Program for the Japan Diet on Serum LDL-Cholesterol Concentration in Patients with Dyslipidemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, N.; Osaki, N.; Takase, H.; Suzuki, J.; Suzukamo, C.; Nirengi, S.; Suganuma, A.; Shimotoyodome, A. The study of metabolic improvement by nutritional intervention controlling endogenous GIP (Mini Egg study): A randomized, cross-over study. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Gu, J.; Cai, X.; Guo, Q.; Bao, L.; et al. Sustaining Effect of Intensive Nutritional Intervention Combined with Health Education on Dietary Behavior and Plasma Glucose in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Nutrients 2016, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaga, K.; Mitamura, R. Effects of Undaria pinnatifida (Wakame) on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Levels in Humans: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, F.; Ikeda, K.; Joo, E.; Fujita, Y.; Yamane, S.; Harada, N.; Inagaki, N. The Effect of White Rice and White Bread as Staple Foods on Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.M.; Caldas, A.P.; Oliveira, L.L.; Bressan, J.; Hermsdorff, H.H. Saturated fatty acids trigger TLR4-mediated inflammatory response. Atherosclerosis 2016, 244, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, L.; Hopstock, L.A.; Grimsgaard, S.; Carlsen, M.H.; Lundblad, M.W. Intake of Vegetables, Fruits and Berries and Compliance to “Five-a-Day” in a General Norwegian Population—The Tromsø Study 2015–2016. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa, K.; Watanabe, K.; Kumazawa, Y.; Nagaoka, I. Phytochemicals and Vitamin D for a Healthy Life and Prevention of Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kanesaka, M.; Kawauchi, H.; Jirillo, E.; Kumazawa, Y. Suppression of type-I allergic responses by oral administration of grape marc fermented withLactobacillus plantarum. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2010, 32, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, I.J. Nutrition Therapy Regulates Caffeine Metabolism with Relevance to NAFLD and Induction of Type 3 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Kikuchi, S.-I.; Hasunuma, R.; Maruyama, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kumazawa, Y. A Citrus Flavonoid Hesperidin Suppresses Infection-Induced Endotoxin Shock in Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, K.; Shimizu, Y.; Yokoi, Y.; Ohira, S.; Hagiwara, M.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Aizawa, T.; Ayabe, T. Decrease of α-defensin impairs intestinal metabolite homeostasis via dysbiosis in mouse chronic social defeat stress model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Starving our Microbial Self: The Deleterious Consequences of a Diet Deficient in Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.J. Single Gene Inactivation with Implications to Diabetes and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome. J. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.J. Anti-Aging Genes Improve Appetite Regulation and Reverse Cell Senescence and Apoptosis in Global Populations. Adv. Aging Res. 2016, 5, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, D.C.; Scapagnini, G.; Willcox, B.J. Healthy aging diets other than the Mediterranean: A focus on the Okinawan diet. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, S.; Iwama, N.; Kawabata, T.; Hasegawa, K. Longevity and Diet in Okinawa, Japan: The Past, Present and Future. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2003, 15, S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devranis, P.; Vassilopoulou, Ε.; Tsironis, V.; Sotiriadis, P.M.; Chourdakis, M.; Aivaliotis, M.; Tsolaki, M. Mediterranean Diet, Ketogenic Diet or MIND Diet for Aging Populations with Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Life 2023, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatsuka, N.; Harada, K.; Ando, M.; Nagao, K. Measurement of the radical scavenging activity of chicken jelly soup, a part of the medicated diet, ‘Yakuzen’, made from gelatin gel food ‘Nikogori’, using chemiluminescence and electron spin resonance methods. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 18, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).