Abstract

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a novel and rapidly evolving class of targeted therapeutics that combine the high specificity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with the potent cytotoxic effects of small-molecule drugs. These engineered molecules are designed to selectively deliver cytotoxic agents to specific cells, thereby reducing off-target toxicity and enhancing therapeutic efficacy. In oncology, ADCs have already demonstrated significant clinical success, particularly in the treatment of hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Agents such as trastuzumab emtansine and brentuximab vedotin exemplify how ADCs can effectively target cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy tissues. This review comprehensively explores the key aspects of the use of ADCs in autoimmune disorders, which is an evolving field in immunotherapy.

1. Introduction

Autoimmune disorders are a heterogenous group of diseases in which the immune system produces autoantibodies or specific T cells that target self-organs and tissues. They can be classified as organ-specific disorders, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and myasthenia gravis, and systemic disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). There is evidence that, in the genesis of autoimmune disorders, several factors interact with each other. These factors are genetic, immunological, endocrines, and environmental; however, the author does not expand on these concepts, as the aim of the review is to give a broad introduction on the use of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) in autoimmune disorders. Although originally developed for cancer therapy, the potential of ADCs in autoimmune diseases is now being explored. Autoimmune condition conventional therapies often involve broad immunosuppressants, which can lead to systemic side effects and an increased risk of infections. In this context, ADCs offer a promising alternative by enabling targeted immunomodulation. By directing the cytotoxic payload specifically to pathogenic immune cells—such as autoreactive B cells or T cells—ADCs can suppress disease activity while preserving overall immune function [1,2].

ADCs were a breakthrough in oncology, combining monoclonal antibodies with potent cytotoxic agents to precisely target cancer cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissues. Agents like trastuzumab emtansine and brentuximab vedotin exemplify their success in treating hematological malignancies and solid tumors, demonstrating significant clinical efficacy. Although initially developed for cancer, ADCs are now being explored for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, aiming to selectively deplete pathogenic immune cells. Advances in target identification and linker technology are crucial for expanding ADC use beyond oncology, with promising approaches targeting autoreactive B cells in conditions like SLE and MS [3,4,5].

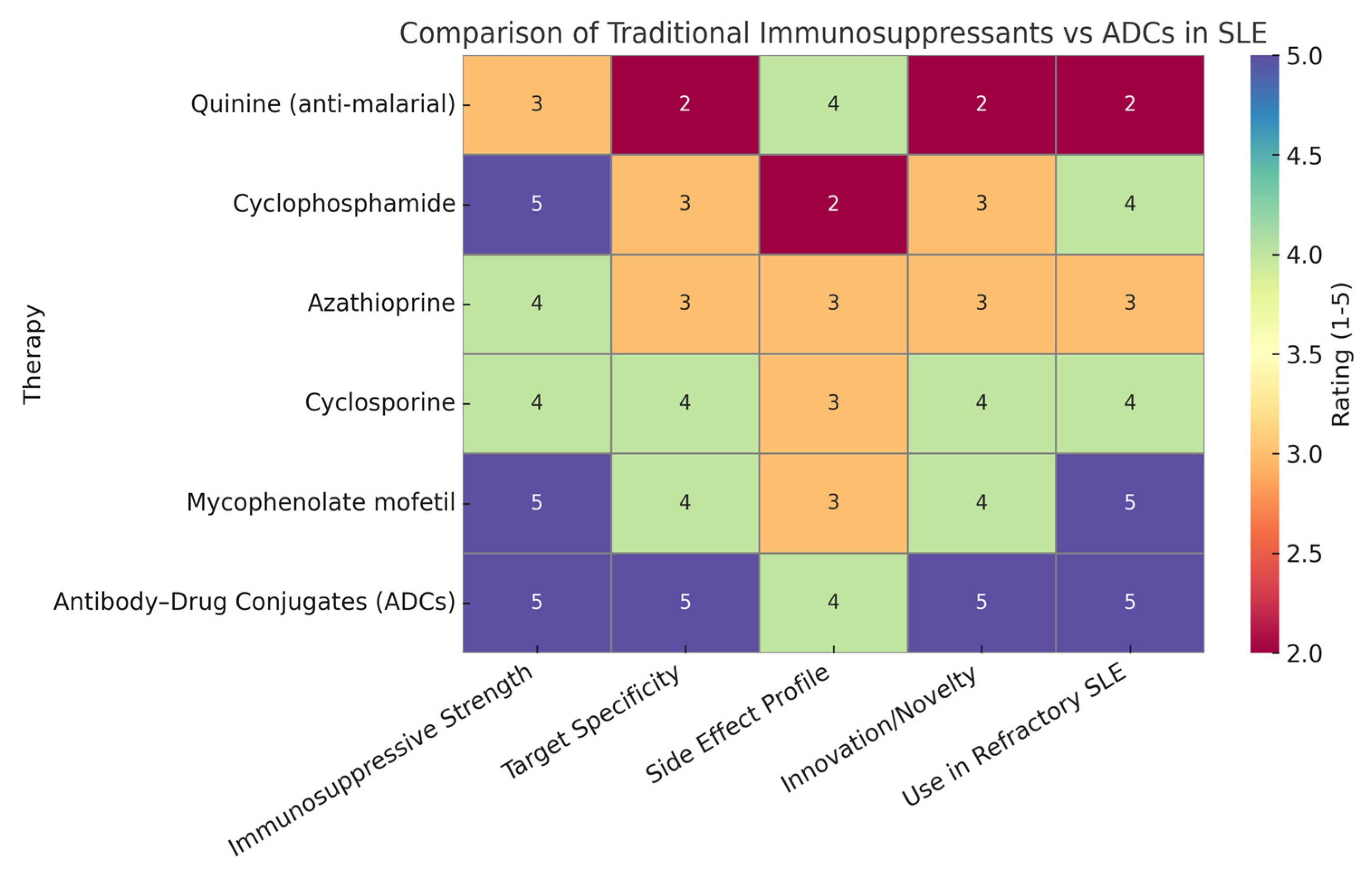

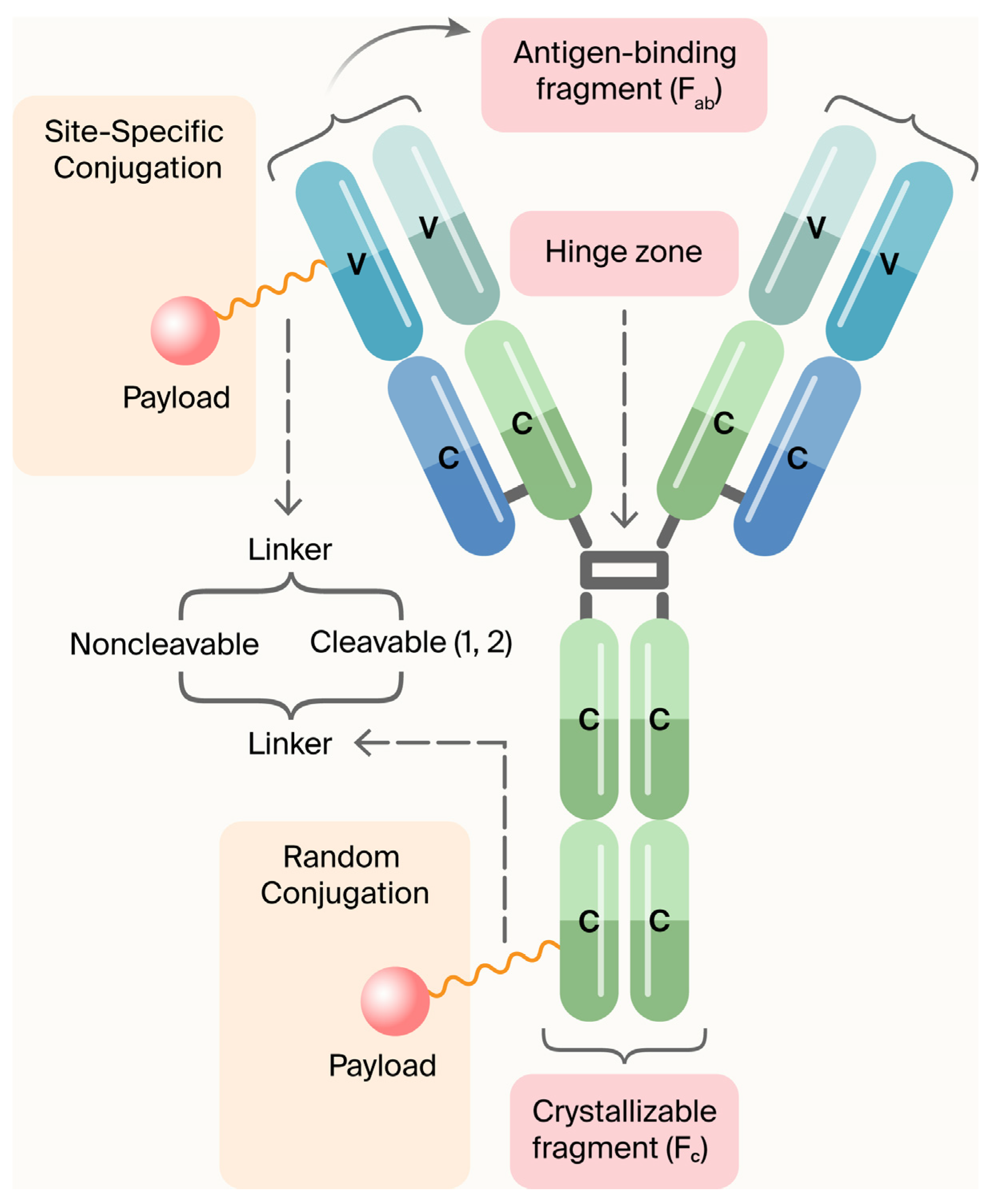

ADCs are composed of three main components (Figure 1) [5]:

- Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): Target disease-specific antigens.

- Linkers: Ensure stable attachment and release of the payload in target cells.

- Payload (cytotoxic agent or immunomodulator): Induces apoptosis or modifies immune cell function.

Figure 1.

Components of an ADC. In the United States, FDA-approved antibody–drug conjugates utilize two methodologies to bind to chemically active agents: (a) cleavable linkers (peptide linkers split by cathepsin B); (b) non-cleavable linkers (non-cleavable thioether linkers that dispense the medical preparation after the monoclonal antibody has dissipated). Usage of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) as therapeutic agents for the management or cure of a wide variety of diseases is well known, especially their use in cancer treatment. Due to the limitations of mAbs’ antitumor efficacy, attempts are being made to improve the potential efficacy of mAbs. These efforts encompass the conjugation of mAbs to radionuclides, fusion with immunotoxins, or coupling to ADCs. The coupling of a mAb with a cytotoxic agent or a small molecule is called payload [5]. Figure modified by MDPI Author Services [english-103829].

Figure 1.

Components of an ADC. In the United States, FDA-approved antibody–drug conjugates utilize two methodologies to bind to chemically active agents: (a) cleavable linkers (peptide linkers split by cathepsin B); (b) non-cleavable linkers (non-cleavable thioether linkers that dispense the medical preparation after the monoclonal antibody has dissipated). Usage of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) as therapeutic agents for the management or cure of a wide variety of diseases is well known, especially their use in cancer treatment. Due to the limitations of mAbs’ antitumor efficacy, attempts are being made to improve the potential efficacy of mAbs. These efforts encompass the conjugation of mAbs to radionuclides, fusion with immunotoxins, or coupling to ADCs. The coupling of a mAb with a cytotoxic agent or a small molecule is called payload [5]. Figure modified by MDPI Author Services [english-103829].

In autoimmune disorders, the aim is to selectively deplete autoreactive immune cells (e.g., B cells, plasma cells, or T cells) without affecting healthy tissues [1].

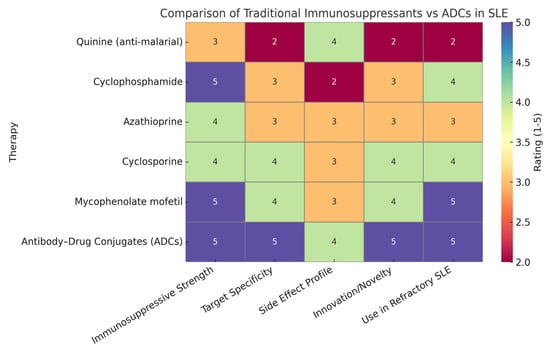

1.1. Comparative Analysis: Traditional Immunosuppressants vs. ADCs in SLE

The growth of the chemical industry has led to the development of key immunosuppressants like cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and cyclosporine, improving SLE management but with limitations such as off-target effects, toxicity, and variable patient responses due to broad immune suppression [4]. ADCs offer a paradigm shift in SLE by combining antibody specificity with potent drugs to selectively target and eliminate pathogenic immune cells while preserving protective immunity [5].

1.2. Justification of Heatmap Ratings

Heatmap ratings can be used to summarize the comparative strengths of traditional immunosuppressants versus antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) across key therapeutic parameters. ADCs scored highly in immunosuppressive strength due to their potent, targeted mechanism of action, often matching or exceeding traditional therapies. They received top ratings for target specificity, reflecting their precision in binding disease-specific antigens like CD19 and BCMA, unlike older drugs that act broadly. The side effect profile was rated slightly lower for ADCs than for specificity because, although targeted delivery reduces systemic toxicity, long-term safety data are still maturing. In terms of innovation, ADCs clearly surpassed traditional therapies, representing a major advancement in immunotherapy. Their high rating for use in refractory SLE is based on promising preclinical and clinical findings, showing their ability to eliminate resistant immune cells where traditional treatments often fail. Overall, the heatmap (Figure 2) highlights the evolving advantage of ADCs in modern autoimmune disease management [6]. Figure 1 shows a comparison of traditional immunosuppressants versus ADCs in SLE, as described above.

Figure 2.

The heatmap provides a strategic visual comparison that underscores the growing potential of ADCs in transforming lupus therapeutics. Though still largely in the investigational phase for SLE, their precision, potency, and innovation suggest they may soon rival or surpass traditional treatments in efficacy and safety.

1.3. Clinical Relevance

Early-stage studies indicate that ADCs can target B cells, such as anti-CD19 and anti-BCMA, potentially inducing durable remission in autoimmune diseases like lupus, especially for patients who are intolerant to traditional therapies. Future advancements should aim to develop payloads that modulate immune activity without causing cytotoxicity, offering a promising approach for chronic conditions [7].

2. Mechanism of Action

2.1. Mechanism of Action of Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs) in Autoimmune Diseases

ADCs combine monoclonal antibodies, linkers, and payloads to deliver potent agents precisely to target cells. While these have been successful in oncology, they are now emerging as promising treatments for autoimmune diseases, aiming to reduce disease activity while minimizing broad immunosuppression through a targeted, precision medicine approach [8].

2.2. Monoclonal Antibody (mAb)

The antibody component of ADCs targets specific antigens on diseased cells, such as CD19, CD20, CD22, or CD38 on autoreactive B or T cells, ensuring the precise delivery of payloads [4]. This selectivity aims to treat autoimmune diseases like SLE, RA, and MS while minimizing effects on healthy immune cells.

2.3. Linker

Linkers connect the antibody to the payload and must be stable in circulation to prevent premature release, but cleavable within target cells can activate the drug [9]. Cleavable linkers respond to intracellular conditions like low pH or enzymes, while non-cleavable linkers depend on antibody degradation. The type of linker impacts ADC stability, efficacy, and safety [10].

2.4. Payload (Cytotoxic Agent or Immunomodulator)

In oncology, ADC payloads are highly potent cytotoxins, but in autoimmune diseases, they may selectively eliminate autoreactive immune cells or modulate their activity. For example, delivering apoptosis-inducing agents to autoreactive B cells or using immunomodulatory payloads to inhibit signaling pathways can achieve precise immune suppression, minimizing the side effects of conventional drugs [11,12,13].

2.5. Cellular Mechanism of ADCs

ADCs bind to specific antigens on target immune cells, leading to internalization via receptor-mediated endocytosis [14]. The complex is trafficked to lysosomes, where the linker is cleaved, releasing the payload [15]. Cytotoxic agents induce cell death through mechanisms like DNA damage, while immunomodulatory payloads suppress inflammation and immune activation, targeting autoimmune pathways [16,17].

2.6. Relevance in Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune diseases involve autoreactive lymphocytes escaping immune tolerance [18], and traditional immunosuppressants have broad effects with serious side effects [8]. ADCs offer targeted therapies, such as CD19 or CD22 ADCs to deplete autoreactive B cells in SLE and MS, CD25 ADCs to prevent relapses, and CD38 ADCs to reduce autoantibodies in blistering diseases, improving specificity and safety [8,18].

3. Targets in Autoimmune Diseases for Antibody–Drug Conjugate (ADC) Therapy

ADCs in autoimmune diseases focus on targeting specific immune cells, such as B cells and plasma cells, with markers like CD19, CD20, CD22, BCMA, and CD38. Despite the complexity, these promising targets are under investigation for their therapeutic potential [8,19,20,21].

3.1. CD19, CD20, and CD22

CD19, CD20, and CD22 are B cell surface proteins involved in different development stages. Targeting these with ADCs in autoimmune diseases like SLE, RA, and MS allows for durable B cell depletion, reducing autoantibody production, BCR signaling, and disease flares by inducing apoptosis [21,22].

3.2. BCMA (B Cell Maturation Antigen)

BCMA is a transmembrane receptor expressed almost exclusively on plasma cells and a subset of late-stage B cells. Its restricted expression pattern and crucial role in plasma cell survival make it an attractive target for ADC therapy in diseases characterized by pathogenic autoantibody production [23].

3.3. CD38

CD38, which is upregulated in inflammatory immune cells in autoimmune conditions, can be targeted with ADCs to selectively deplete hyperactivated cells, offering a pathogen-specific therapy with reduced risk of broad immunodeficiency [24].

4. Emerging ADCs in Clinical/Preclinical Studies

ADCs targeting immune markers like CD19, CD22, CD38, and BCMA are emerging therapies for autoimmune diseases. They offer precise, cell-specific treatments by inducing apoptosis or modulating immune cell function, aiming to improve efficacy while minimizing broad immunosuppression and preserving overall immune health [25,26].

4.1. VAY736 (Ianalumab)—BAFF-R Target-SLE-Phase 2

VAY736 (Ianalumab) targets BAFF-R to inhibit B cell survival, reducing flares and autoantibodies in SLE. It is currently in Phase 2 trials with promising early results [27,28]. Its successes and limitations are as follows:

- Successes: Effective depletion of BAFF-R + B cells with improvement in disease indices.

- Limitations: Long-term data on B cell reconstitution and infection risk are pending.

4.2. TAK-079 Is a Fully Human IgG1λ Monoclonal Antibody Targeting CD38

TAK-079, an anti-CD38 antibody, showed efficacy in primate arthritis models by reducing joint damage, inflammation, and depleting CD38-positive cells, with no significant side effects, indicating potential for us in the treatment of autoimmune diseases like RA [29,30].

4.3. ABBV-3373 Is an Innovative Antibody–Drug Conjugate (ADC)

ABBV-3373, an ADC combining anti-TNF antibody and glucocorticoid receptor modulator, showed superior reduction in rheumatoid arthritis activity compared to adalimumab in a Phase IIa trial. At week 12, it achieved better DAS28-CRP scores, with 70.6% maintaining response at week 24. The safety profile was similar, though one anaphylactic shock occurred. These results support the further development of ABBV-3373 for RA treatment [31].

4.4. CD45-Targeted Antibody–Drug Conjugates (CD45-ADCs)

Magenta Therapeutics developed CD45-targeted antibody–drug conjugates as a less toxic conditioning method for auto-HSCT in autoimmune diseases. In preclinical models, they efficiently depleted immune cells and achieved full donor chimerism, delaying or reducing disease severity. This targeted approach offers a safer, effective alternative to traditional chemotherapy, potentially expanding the use of auto-HSCTs for autoimmune conditions by lowering the associated toxicity risks [32].

4.5. Development of an Anti-IL-7R Monoclonal Antibody (A7R) Conjugated with Cytotoxic Agents SN-38 and Monomethyl Auristatin E (MMAE)

IL-7R-targeting antibody–drug conjugates effectively reduced inflammation in autoimmune arthritis models, outperforming traditional steroids. This approach suggests that targeting IL-7R+ cells could offer a novel and potent treatment for refractory autoimmune diseases, especially those resistant to conventional steroid therapies, providing a promising strategy for improved disease management [33].

5. Antibody–Drug Conjugates in Autoimmune Diseases: A Discussion

5.1. Target Specificity vs. Conventional Therapy

Immunosuppressive ADCs target disease-causing immune cells with precision, reducing off-target effects and toxicity compared to broad-acting drugs like corticosteroids and Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARDs). Early preclinical studies show they can deliver immunomodulating agents directly to autoimmune cells, enhancing efficacy and minimizing collateral damage, offering a promising, more targeted approach for treating autoimmunity [34,35,36].

5.2. Reduced Dosing Frequency and Pharmacokinetic Advantages

ADCs have a long antibody half-life, allowing infrequent dosing that enhances compliance and convenience. They target diseased tissues directly, needing lower doses than systemic therapies. For instance, a DMARD payload in RA can reduce high doses. Overall, ADCs’ delivery efficiency and prolonged circulation provide pharmacokinetic and dosing benefits over traditional immunosuppressants, maintaining consistent therapeutic levels with fewer doses [36,37,38].

5.3. Disease-Modifying Potential and Long-Term Remission

ADCs target pathogenic immune cells for lasting autoimmune remission. Early results show improved rheumatoid arthritis scores and reduced skin fibrosis, indicating their potential as disease-modifying agents that eliminate or reprogram immune drivers for more durable responses [39,40,41,42,43].

5.4. Challenges in ADC Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases

ADCs in autoimmunity face challenges such as selecting targets that are highly expressed on pathogenic cells but minimally on healthy ones; strategies like targeting dividing cells can improve specificity [35]. Payload toxicity and bystander effects require stable linkers and careful payload choices to avoid harming normal tissues [36]. Managing immune suppression to prevent infections and hypogammaglobulinemia is vital, along with minimizing immunogenicity through humanized antibodies to reduce anti-drug antibodies [44]. Table 1 shows a list of ADCs tested for autoimmune diseases.

Table 1.

This list summarizes ADCs tested for autoimmune diseases, detailing targets, payloads, linkers, and testing status, aiming for targeted, safer therapies [36].

6. Conclusions

Emerging ADCs target autoimmune cells with immunomodulatory agents, such as anti-CD74-fluticasone and anti-CD70-budesonide, aim to replicate glucocorticoid effects with fewer side effects. They can also suppress or eliminate autoreactive lymphocytes and silence genes via siRNA conjugates. The challenges faced by those developing these treatments include optimizing linker stability, payload potency, and safety, but early results in diseases like SLE and systemic sclerosis show promise for more targeted, effective, and safer therapies beyond oncology [36,53,54].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study is included within the manuscript and its referenced sources, ensuring comprehensive access to the relevant data for further examination and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, L.; Yin, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q.; Gao, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Xin, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, M.; et al. A rationally designed CD19 monoclonal antibody-triptolide conjugate for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 4560–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Pandit, B.R.; Unakal, C.; Vuma, S.; Akpaka, P.E. A Comprehensive Review About the Use of Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2025, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Vico, A.; Frazzei, G.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Tas, S.W. Targeting B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune diseases: From established treatments to novel therapeutic approaches. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2149675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Barbosa, O.A.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pandit, B.; Umakanthan, S.; Akpaka, P.E. Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Molecules Involved in Its Imunopathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettinato, M.C. Introduction to Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Antibodies 2021, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felten, R.; Scher, F.; Sibilia, J.; Chasset, F.; Arnaud, L. Advances in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: From back to the future, to the future and beyond. Jt. Bone Spine 2019, 86, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 4025–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xiao, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3889–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamkundu, S.; Liu, C.F. Lysosomal-Cleavable Peptide Linkers in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantasinghar, A.; Sunildutt, N.P.; Ahmed, F.; Soomro, A.M.; Salih, A.R.C.; Parihar, P.; Memon, F.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kang, I.S.; Choi, K.H. A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of antibody drug conjugate. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holborough-Kerkvliet, M.D.; Kroos, S.; van de Wetering, R.; Toes, R.E.M. Addressing the key issue: Antigen-specific targeting of B cells in autoimmune diseases. Immunol. Lett. 2023, 259, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, F.; Dal Bo, M.; Macor, P.; Toffoli, G. A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: From the conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1274088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: The “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickens, C.J.; Christopher, M.A.; Leon, M.A.; Pressnall, M.M.; Johnson, S.N.; Thati, S.; Sullivan, B.P.; Berkland, C. Antigen-drug conjugates as a novel therapeutic class for the treatment of antigen-specific autoimmune disorders. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, T.; Sekulovski, M.; Bogdanova, S.; Vasilev, G.; Peshevska-Sekulovska, M.; Miteva, D.; Georgiev, T. Intravenous Immunoglobulins as Immunomodulators in Autoimmune Diseases and Reproductive Medicine. Antibodies 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, K. CD19: A promising target for systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1454913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expanding New Trends and Technologies in ADC Therapeutics. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/whitepaper/20250218/Expanding-new-trends-and-technologies-in-ADC-therapeutics.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- McPherson, M.J.; Hobson, A.D. Pushing the Envelope: Advancement of ADCs Outside of Oncology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2078, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemlinger, S.M.; Cambier, J.C. Therapeutic tactics for targeting B lymphocytes in autoimmunity and cancer. Eur. J. Immunol. 2024, 54, 2249947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Burrows, P.D.; Wang, J.Y. B cell development and maturation. In B Cells in Immunity and Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Cheng, Q.; Laurent, S.A.; Thaler, F.S.; Beenken, A.E.; Meinl, E.; Krönke, G.; Hiepe, F.; Alexander, T. B-Cell Maturation Antigen (BCMA) as a Biomarker and Potential Treatment Target in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarbati, S.; Benfaremo, D.; Viola, N.; Paolini, C.; Svegliati Baroni, S.; Funaro, A.; Moroncini, G.; Malavasi, F.; Gabrielli, A. Increased expression of the ectoenzyme CD38 in peripheral blood plasmablasts and plasma cells of patients with systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1072462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazzei, G.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; de Jong, B.A.; Siegelaar, S.E.; van Schaardenburg, D. Preclinical Autoimmune Disease: A Comparison of Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Multiple Sclerosis and Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 899372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zian, Z.; Anka, A.U.; Abdullahi, H.; Bouallegui, E.; Maleknia, S.; Azizi, G. Chapter 12—Clinical efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies in autoimmune diseases. In Breaking Tolerance to Antibody-Mediated Immunotherapy, Resistance to Anti-CD20 Antibodies and Approaches for Their Reversal; William, C.S.C., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 273–298. ISBN 9780443192005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.J.; Fox, R.; Dörner, T.; Mariette, X.; Papas, A.; Grader-Beck, T.; Fisher, B.A.; Barcelos, F.; De Vita, S.; Schulze-Koops, H.; et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous ianalumab (VAY736) in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Hernández, J.; Ignatenko, S.; Gordienko, A.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Romanowska-Prochnicka, K.; Shen, N.; Ciferská, H.; Kodera, M.; Wei, J.C.C.; et al. POS0120 safety and efficacy of subcutaneous (SC) dose ianalumab (VAY736; anti-Baffr mAb) administered monthly over 28 weeks in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, W.; Carsillo, M.; Yuan, J.; Idamakanti, N.; Wagoner, M.; Shi, P.; Xia, C.Q.; Glennda, S.; Lachy, M.; Jonathan, Z.; et al. A reduction in B, T, and natural killer cells expressing CD38 by TAK-079 inhibits the induction and progression of collagen-induced arthritis in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedyk, E.R.; Zhao, L.; Koch, A.; Smithson, G.; Estevam, J.; Chen, G.; Lahu, G.; Roepcke, S.; Lin, J.; Mclean, L. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the anti-CD38 cytolytic antibody TAK-079 in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, B.; McPherson, M.; Hernandez, A.; Goess, C.; Mathieu, S.; Waegell, W.; Bryant, S.; Hobson, A.; Ruzek, M.; Pang, Y.; et al. POS0365 anti-TNF glucocorticoid receptor modulator antibody drug conjugate for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, M.A.; Klodowska-Duda, G.; Maciejowski, M.; Potemkowski, A.; Li, J.; Patra, K.; Wesley, J.; Madani, S.; Barron, G.; Katz, E.; et al. Safety and tolerability of inebilizumab (MEDI-551), an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody, in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis: Results from a phase 1 randomised, placebo-controlled, escalating intravenous and subcutaneous dose study. Mult. Scler. 2019, 25, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, M.; Manabe, S.; Matsumura, Y. Immunoregulation by IL-7R-targeting antibody-drug conjugates: Overcoming steroid-resistance in cancer and autoimmune disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Braunstein, Z.; Chen, J.; Wei, Y.; Rao, X.; Dong, L.; Zhong, J. Precision Medicine in Rheumatic Diseases: Unlocking the Potential of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Roy, P.; Jirvankar, P. Antibody-Drug Conjugates vs. Traditional Biologics: A Comparative Analysis of Rheumatic Disease Management. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2025, 15, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, L.B.; Bule, P.; Khan, W.; Chella, N. An Overview of the Development and Preclinical Evaluation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Non-Oncological Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, D.; Yang, J.; Salam, M.A.; Sengupta, S.; Al-Amin, Y.; Mustafa, S.; Khan, M.A.; Huang, X.; Pawar, J.S. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: The Paradigm Shifts in the Targeted Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1203073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, T.; Vaidya, A.; Ravindran, S. Therapeutic potential of antibody–drug conjugates possessing bifunctional anti-inflammatory action in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2024, 26, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hua, H. An immunomodulatory antibody–drug conjugate targeting BDCA2 strongly suppresses plasmacytoid dendritic cell function and glucocorticoid responsive genes. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Codina, A.; Nevskaya, T.; Baron, M.; Appleton, C.T.; Cecchini, M.J.; Philip, A.; El-Shimy, M.; Vanderhoek, L.; Pinal-Fernández, I.; Pope, J.E. Brentuximab vedotin for skin involvement in refractory diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: An open-label trial. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, L.; Chen, J.Y.; Singh, R.; Baldwin, W.M.; Fox, D.A.; Lindner, D.J.; Martin, D.F.; Caspi, R.R.; Lin, F. A CD6-targeted antibody–drug conjugate as a potential therapy for T cell-mediated disorders. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e172914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F.; Aelion, J.; Rojkovich, B.; Zubrzycka-Sienkiewicz, A.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Arikan, D.; Ronilda, D.; Pang, Y.; Kupper, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of ABBV-3373, a Novel Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Antibody–Drug Conjugate, in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis Despite Methotrexate Therapy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Phase IIa Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharopoulos, C.; Lialios, P.-P.; Samarkos, M.; Gogas, H.; Ziogas, D.C. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Functional Principles and Applications in Oncology and Beyond. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmettler, S.; Ong, M.S.; Farmer, J.R.; Choi, H.; Walter, J. Hypogammaglobulinemia, late-onset neutropenia, and infections following rituximab therapy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 130, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.E.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Du, J.; Luo, X.; Deshmukh, V.; Kim, C.H.; Lawson, B.R.; Tremblay, M.S.; et al. An immunosuppressive antibody–drug conjugate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3229–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandish, P.E.; Palmieri, A.; Antonenko, S.; Beaumont, M.; Benso, L.; Cancilla, M.; Cheng, M.; Fayadat-Dilman, L.; Feng, G.; Figueroa, I.; et al. Development of Anti-CD74 Antibody–Drug Conjugates to Target Glucocorticoids to Immune Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibtehaj, N.; Huda, R. High-dose BAFF receptor specific mAb-siRNA conjugate generates Fas-expressing B cells in lymph nodes and high-affinity serum autoantibody in a myasthenia mouse model. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 176, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Codina, A.; Nevskaya, T.; Pope, J. OP0172 Brentuximab Vedontin for Skin Involvement in Refractory Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis, Interim Results of a Phase IIB Open-Label Trial. BMJ 2021, 80, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Bhang, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.; Hahn, S.K. Tocilizumab–alendronate conjugate for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017, 28, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Tsuneyoshi, Y.; Matsushita, K.; Sunahara, N.; Matsuda, T.; Yoshida, H.; Komiya, S.; Onda, M.; Matsuyama, T. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of a recombinant immunotoxin against folate receptor β on the activation and proliferation of rheumatoid arthritis synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 2006, 54, 3126–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, G.; Scheinman, R.I.; Holers, V.M.; Banda, N.K. A new approach for the treatment of arthritis in mice with a novel conjugate of an anti-C5aR1 antibody and C5 small interfering RNA. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5446–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Olsen, O.; D’Souza, C.; Shan, J.; Zhao, F.; Yanolatos, J.; Hovhannisyan, Z.; Haxhinasto, S.; Delfino, F.; Olson, W. Development of Novel Glucocorticoids for Use in Antibody-Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 11958–11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.B. Brentuximab Vedotin Enters Phase 2 Trials & More. 2015. Available online: https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/brentuximab-vedotin-enters-phase-2-trials-more/#:~:text=drug%20conjugate%20,1 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Leung, D.; Wurst, J.M.; Liu, T.; Martinez, R.M.; Datta-Mannan, A.; Feng, Y. Antibody Conjugates-Recent Advances and Future Innovations. Antibodies 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ji, M.; Xiao, P.; Gou, J.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y. Glucocorticoids-based prodrug design: Current strategies and research progress. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).