Abstract

The modelling of plasma–wall interactions (PWIs) depends on distributions describing the angle and energy distribution of particles scattered at the first wall of fusion devices. Most PWI codes rely on extensive tables based on data from reflection simulations, employing a Monte Carlo method. At first glance, the uncertainty distribution of the data should be assumed Gaussian. However, in order to obtain the resulting particle distribution, the reflected ions are counted within angle sections of the upper hemisphere, which hints to a Poisson uncertainty distribution. In this paper, we let Bayesian model comparison decide which uncertainty model should be taken.

1. Introduction

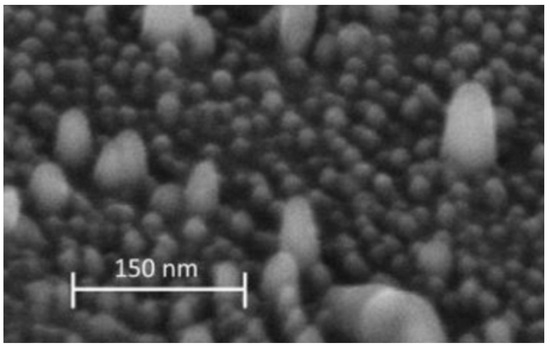

Conventional plasma–wall interaction modelling in SOLPS [1] and EIRENE [2] has focused on sputtering-driven wall erosion, with well-established understanding of preferential sputtering, recoil implantation, and roughness-induced yield reduction (see Figure 1 for a real surface under ion irradiation).

Figure 1.

SEM image of the surface of an EUROFER sample (2% W in Fe) under ion irradiation with 200 eV D [3].

However, the impact of evolving surface morphology on the angular and energy distributions of reflected particles—particularly in non-diffuse reflection regimes—remains inadequately addressed in current frameworks. Although in principle, simulations of dynamically evolving 3D morphologies are feasible, they are computationally still very ambitious, so a practicable way would be to focus on reference surfaces from which the outcome for the surface under investigation can be inferred by interpolation. Unlike sputter yields, variations in reflected particle distributions entail not only changes in magnitude but also fundamental shifts in angular characteristics: specular reflection is often significantly diminished, and for oblique incidence, the peak of the reflection distribution may unexpectedly reverse direction, aligning more closely with the incoming ion flux. Crucial input quantities for the PWI codes are the energy and angular distributions of the particles incident on the wall and those (re-)entering plasma. These distributions are obtained by modelling ion reflections from the surface of a given atomic composition, with reflection simulations carried out by numerical codes (e.g., SDTrimSP-1D [4]) in astonishingly high accordance with experimental results. From stepwise variations over the incident energy and impact angle (and a multiverse of impact ions and surface compositions), extensive tables are generated. To efficiently represent the reflected particle distributions from numerical simulations without excessive data storage, we employ orthonormal hemispherical basis functions to decompose the angular and energy dependence of the distribution . The expansion coefficients are determined via linear regression and interpolated as a function of incident energy. This approach reduces the high-dimensional data—spanning multiple energy steps and angular sectors—into a compact set of coefficients, effectively encoding the essential features of the distribution. These coefficients serve as a minimal, physically meaningful representation of the reflection behaviour for a given material and geometry, enabling straightforward tabulation and direct integration into PWI codes. However, since the simulation codes invoke a random principle to describe the collision processes of the impacting ions with the atoms of the target, the results will be hampered by noise with unknown statistical nature. While a Monte Carlo method is invoked to decide if a collision takes place, the resulting particle distribution for reflected particles making their way into the upper hemisphere reside on particle counting within binned angular sections of this hemisphere. Thus, we have arguments for both a Gaussian and a Poisson nature regarding the uncertainty of these results. A Bayesian model comparison will provide additional insights concerning this.

2. Numerical Simulation of Particle Reflection Characteristics

The temporal development of the surface under ion irradiation was simulated using SDTrimSP-2D (version 2.09) [5] for a two-dimensional periodic model system. A deuterium ion beam at 200 eV was employed, impinging on a target which comprised iron, as the bulk material, and tungsten pillars, with a nominal width of 25 Å. The pillars are embedded in the iron matrix beneath a 135 Åthick iron surface layer. By varying the ion fluence, a range of surface states was generated: from a fully covered, atomically flat iron surface to a progressively eroded configuration where tungsten pillars of increasing height are exposed. These morphologies are designed to emulate the microstructural features observed in the SEM image of Figure 1. In a subsequent step, the reflection characteristics of the 200 eV incident deuterium ions were evaluated for each of these morphologically distinct surfaces, with the surface geometry fixed throughout (SDTrimSP-2D in static mode). This procedure provides direct assessment of how surface evolution affects particle reflection.

3. Simulation Results

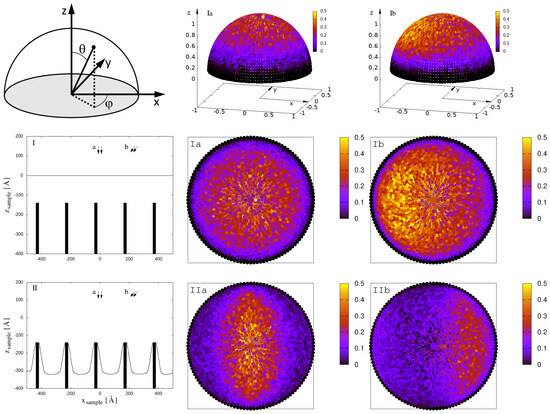

Figure 2 presents the geometry for the ion reflection intensities (first row) shown in the subsequent pictures. The second row depicts the initial state of the target with the embedded tungsten pillar far beneath the iron surface. In the third row, the target was subjected to deuterium irradiation at a fluence of , resulting in sufficient erosion of the iron overlayer to fully expose the underlying tungsten pillars. The resulting surface exhibits a well-defined, periodic microstructure that replicates the roughness morphology observed in the experimental SEM image of Figure 1.

Figure 2.

First row: Geometry for the representations in Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb of reflected D-ion intensities. The D-ions are reflected onto the (-)-polar hemisphere, which is shown from a perpendicular view in the second and third rows. The colour scale in the (-)-polar plots corresponds to the intensity of the reflected D-ions. Different sample surfaces: In the middle row (I), the sample has a clean surface extending in the xy-plane at = 0 Å. Tungsten pillars are buried 140 Å below the surface, and is of no importance for the results in the second row. The sample faces non-destructive perpendicular irradiation from the z-direction (case a, middle panel) or diagonal irradiation from the xz-direction with an incident angle of 45 deg (case b, right panel). In the last row (II), the sample shows a surface generated by 0 deg ion beam with a fluence of 800 atoms/ (left panel), so the tungsten pillars become uncovered, representing a rough surface. Again the sample is exposed to non-destructive irradiation by a D-ion beam with = 200 eV: incident angle: 0 deg (a, middle panel); incident angle: 45 deg (b, right panel).

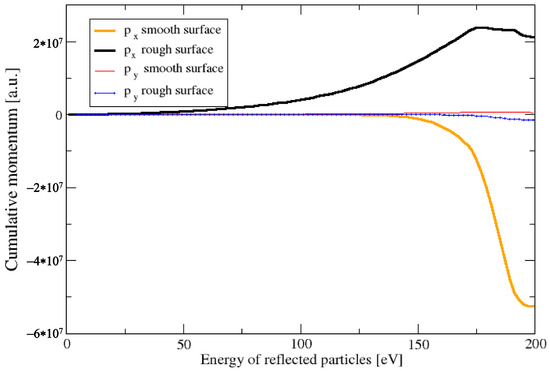

To extract the reflected deuterium ion distributions, the two surface configurations were irradiated with a 200 eV D-beam at either normal incidence (middle panel) or oblique incidence (right panel)—this time in static mode to prevent further surface evolution. As evident from the -polar plots of the reflected particle flux (with and ) in Figure 2, the angular distribution remains azimuthally symmetric—i.e., uniformly distributed in —regardless of surface morphology under normal incidence. However, a striking departure from this behaviour emerges at incidence: while the flat iron surface exhibits near-specular reflection, the presence of exposed tungsten pillars induces a pronounced redirection of the reflected flux toward the incident beam direction. This qualitative shift in reflection dynamics is further corroborated by the momentum distribution of reflected ions, as illustrated in Figure 3, where a clear change in the angular and energy dependence of the reflected flux is observed in the presence of surface structuring.

Figure 3.

Momentum distribution px and py as functions of reflected particle energy for an ion beam angle of 50 deg.

4. Data Compression

The distribution, , encodes the angular and energy-dependent flux of ions scattered into the hemisphere defined by polar angle and azimuth . It is conditioned on the incident energy , incidence angles and (commonly fixed at ), and critically, on the surface state S, as demonstrated in this study. Direct storage of the full three-dimensional distribution is impractical due to high dimensionality and limited feasibility of coarse graining. To overcome this, we adopt a spectral representation using orthonormal basis functions: the original data are projected onto a truncated set of basis elements, yielding a compact set of expansion coefficients that capture the essential features of the reflection behaviour. Based on the fact that the angular distribution of reflected particles exhibits a two-dimensional structure on the hemisphere, a real hemispherical harmonic basis [6] provides a natural and efficient framework for this decomposition:

Hemispherical harmonics form a complete and orthogonal basis set over the unit hemisphere:

with , , , , . and associated Legendre polynomials .

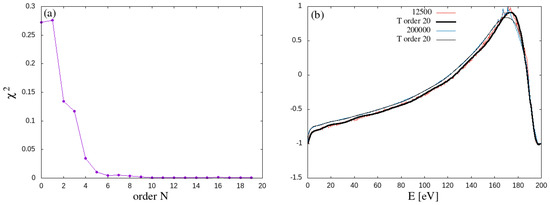

The -minimization trend as a function of the hemispherical basis truncation order is depicted in Figure 4a. The fit quality improves rapidly with increasing order, and by an order of 10, the value reaches a plateau consistent with overfitting, signalling that the expansion has captured the dominant features of the distribution. In the hemispherical harmonic expansion, the number of independent coefficients scales as the square of the order, which yields parameters. The original angular data, sampled at intervals over a grid, correspond to discrete points. Consequently, the basis representation reduces the data dimensionality by a factor of , achieving substantial compression without significant loss of physical fidelity.

Figure 4.

(a) -values as function of order N of the hemispherical basis functions; (b) Chebyshev fits to the hemispherical coefficient .

To enable a complete and efficient replacement of the full scattering data in PWI codes with a compact representation of the reflected ion distribution as defined in Equation (1), the energy dependence of the expansion coefficients must be explicitly incorporated. While these coefficients may vary non-uniformly across the energy range , their values are constrained within this interval. This bounded support makes Chebyshev polynomials particularly suitable for approximating (cf. Chapter 5.8 in [7]). Figure 4b presents a 20-degree Chebyshev fit to the coefficient for two reflected deuterium distributions at = 200 eV. Despite statistical fluctuations inherited from the Monte Carlo sampling in SDTrimSP, the fitted curve exhibits a smooth, monotonic behaviour that is both numerically stable and easily interpolable. The original energy grid—comprising 1000 points spaced at 0.2 eV intervals—thus reduces to just 20 coefficients, yielding a compression factor of 50. Combined with the angular reduction factor of 36 from the hemispherical basis, the total data compression reaches 36 × 50 = 1800, resulting in a highly compact yet physically representative description of the full reflection distribution.

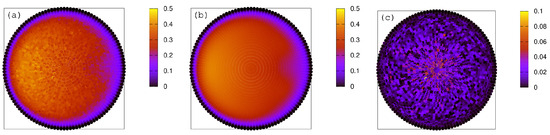

Figure 5 compares the original simulation data with the reconstructed angular distribution derived from the hemispherical basis expansion. On the left, the angular flux of deuterium atoms reflected at = 164 eV from a 200 eV D beam incident at on a tungsten surface is presented (SDTrimSP results). The middle graph depicts the fitted distribution obtained with a real hemispherical harmonic basis of order 10. The reconstructed profiles closely reproduce the structure and anisotropy of the original data, including the pronounced directional bias in the reflection pattern. This close agreement confirms that the basis-based representation successfully captures the essential physics of ion-surface scattering, even under complex morphological conditions.

Figure 5.

(a) Reflection data of D atoms at 164 eV resulting from 200 eV D-ion beam with = 45 deg; (b) derived density; (c) residual distribution obtained by subtracting the fitted angular density (b) from the original data (a), revealing only very small discrepancies.

5. Determination of Uncertainty Nature: Model Comparison

The data originated from numerical simulations of ion bombardment on surfaces. On the one hand, these numerical simulations are carried out by employing a Monte Carlo method, which would suggest a Gaussian nature for the uncertainties . On the other hand, the result is obtained by binning particle numbers of the reflected ions expelled into the upper hemisphere, so we are possibly in the realm of counting events, and the uncertainty in the data is governed by a Poisson distribution, i.e., the square root of the respective data value . Our approach is to let a model comparison decide which error distribution shows a better description of the numerical spread in the data when comparing them with the hemispherical basis functions of Equation (2). We choose a normal distribution for the likelihood function, since the data values are large enough so that the difference between Poisson distribution and Gaussian distribution becomes negligible.

To assign a prior probability distribution for the hyper-parameter , we assume that each error model (i.e., statistical uncertainty from the MC method vs. square root value for the number statistic) is already a valid guess for the uncertainty values, so an uninformative expectation value for the hyper-parameter would be . By virtue of the maximum entropy principle, this results in an exponential prior distribution.

Our goal is to compute the posterior probability in model given the data D. This is expressed via Bayes theorem as

In the absence of any prior preference among competing models, the term of the prior model probabilities is skipped. When performing relative model comparison under identical data D, the marginal likelihood cancels out and only the determination of the global likelihood has to be performed. This is obtained by integrating out the hyper-parameter through marginalization, using the functional forms specified in Equations (3) and (4):

The integrand in Equation (5) exhibits a predominantly Gaussian profile around its mode and allows for an accurate approximation via the Laplace method [8].

Eventually, the calculation of Equation (5) gives a strong result (above a factor of ) for a Poisson uncertainty distribution in the reflected ion data. This can be seen from the relatively smaller variance of the expectation value for hyper-parameter as well. While we obtain for model with uncertainties assumed to be of Gaussian nature, for model —regarding the Poisson nature—the expectation value is . Therefore, model shows a more informative global likelihood with respect to the hyper-parameter .

6. Conclusions

The challenge of efficiently storing and retrieving the full reflection distribution of plasma particles incident on the first wall in a fusion device is addressed through a compact representation based on orthonormal basis functions. We demonstrate that a hemispherical harmonic expansion enables accurate reconstruction of the original angular and energy-dependent reflection data, preserving essential physical features across a range of surface morphologies. Furthermore, our analysis indicates that the statistical uncertainty in the simulation data is better described by a Poisson-like distribution, suggesting that stochastic fluctuations in the Monte Carlo sampling should be treated accordingly in downstream modelling and interpolation schemes.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to each step of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Date sharing is not applicable for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coster, D. An Introduction to SOLPS; Technical Report eDoc: 266663; Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik: Garching, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, D. The EIRENE Code User Manual. Manual Version. 13 September 2019. Available online: https://www.eirene.de/old_eirene/eirene.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Arredondo, R.; Balden, M.; Mutzke, A.; Von Toussaint, U.; Elgeti, S.; Höschen, T.; Schlueter, K.; Mayer, M.; Oberkofler, M.; Jacob, W. Impact of surface enrichment and morphology on sputtering of EUROFER by deuterium. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 23, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, W.; Dohmen, R.; Mutzke, A.; Schneider, R. SDTrimSP; Technical Report IPP 12/3; Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik: Garching, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mutzke, A.; Schneider, R. SDTrimSP-2D; Technical Report IPP 12/4; Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik: Garching, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gautron, P.; Krivánek, J.; Pattanaik, S.N.; Bouatouch, K. A Novel Hemispherical Basis for Accurate and Efficient Rendering. Render. Tech. 2004, 2004, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. Numerical Recipes, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sivia, D.S. Data Analysis: A Bayesian Tutorial; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).