Abstract

This study explores the biopreservative and antioxidant potential of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) isolated from low-sodium vegetable fermentations. Five vegetables, green pepper, tomato, eggplant, carrot, and cabbage, were fermented with varying NaCl concentrations (0–3%) for 45 days. Fifty-six presumptive LAB were isolated, and eight LAB strains exhibiting strong antimicrobial activity against Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus were selected for further analysis. The isolates showed significant tolerance to salinity (6.5–18% NaCl), alkaline pH (9.6), and heat stress (45 °C and 60 °C for 30 min). Antimicrobial assays against eight indicator pathogens confirmed a broad inhibition spectrum attributed to bacteriocin-like substances, while antioxidant assays indicated significant antioxidant activity (27–65%), with strain L10 showing the highest radical scavenging potential (p < 0.05). API 20 STREP profiling revealed three dominant taxa: Leuconostoc, Lactococcus lactis, and Enterococcus faecium. These findings highlight LAB as stress-tolerant, multifunctional strains with promising applications as natural biopreservatives and probiotic candidates for developing functional, low-sodium fermented foods.

1. Introduction

Fermented foods are globally recognized as functional products due to their sensory appeal and health-promoting properties. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), the predominant microorganisms in fermentation, play a dual role in biopreservation and functional enhancement through the production of lactic acid, bacteriocins, and various bioactive compounds [1,2]. The ability of LAB to dominate fermentation ecosystems arises from their acid tolerance and capacity to outcompete spoilage organisms, thereby improving food safety and extending shelf life [3]. Progress in LAB biotechnology has further emphasized their use in functional food production, probiotic formulations, and natural preservation systems [4].

Over the past decade, consumer demand for reduced-sodium foods has increased significantly, driven by global health recommendations to lower sodium intake and prevent hypertension. However, sodium reduction poses a challenge to traditional fermentation practices, as salt acts as a critical selective pressure that governs osmotic balance, microbial selection, and sensory attributes. Research has demonstrated that LAB maintain viability and metabolic activity under moderate salinity (0.5–1%), while producing metabolites that sustain fermentation quality and enhance antioxidant potential [5,6]. Therefore, understanding LAB performance in low-sodium environments is critical for developing safer and healthier fermented vegetable products.

This study explores the microbiological, biochemical characteristics of LAB isolated from traditional low-sodium fermented vegetables. This work aligns with recent research trends emphasizing sustainable bioprocesses, the valorization of biodiversity, and the transition toward plant-based functional foods [7,8].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Fermentation

Fresh vegetables (green pepper, tomato, eggplant, carrot, and cabbage) were purchased from local markets in Agadir, Morocco. The vegetables were washed thoroughly with sterile distilled water, sliced into uniform pieces (2–3 cm), and drained under aseptic conditions. Fermentation was carried out in 500 mL glass jars containing 300 mL of sterile brine prepared with NaCl (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) concentrations of 0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 3% (w/v). The jars were sealed and incubated statically at 25 ± 2 °C for 45 days. Samples were collected aseptically on days 0, 15, 30, and 45 for microbiological and biochemical analyses.

2.2. Microbial Enumeration

At each sampling point, fermentation brines were homogenized and collected aseptically. Samples (1 mL) were serially diluted tenfold in sterile 0.85% (w/v) saline, and 100 µL aliquots of appropriate dilutions were spread-plated on selective and differential media. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were enumerated on de Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) and GM17 agar and incubated anaerobically at 30 °C for 48 h using an Oxoid Gas Pak system. Yeasts and molds were enumerated on potato dextrose agar (PDA), and total coliforms on violet red bile lactose (VRBL) agar. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus were monitored on Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide (TBX) agar and Baird-Parker agar, respectively. All media were purchased from Biokar Diagnostics (Beauvais, France).

2.3. Preliminary Screening and Selection of LAB Isolates

LAB screening was performed following the method described by Elidrissi et al. (2023) [2] with minor modifications. Briefly, LAB were isolated from fermented brines of five vegetables collected after 45 days of spontaneous fermentation. Aliquots (100 µL) from serial dilutions were spread on MRS and GM17 agar and incubated anaerobically at 30 °C for 48 h. Colonies exhibiting typical LAB morphology were purified by repeated streaking. A total of 56 presumptive LAB isolates were obtained, from which eight strains showing strong zones of inhibition against Listeria monocytogenes and S. aureus were selected for detailed characterization. Pure cultures were maintained at 4 °C and preserved in 35% glycerol at –20 °C for long-term storage.

2.4. Biochemical and Physiological Characterization of Isolated LAB

Selected isolates were examined for Gram reaction and catalase activity, and their ability to grow at different NaCl concentrations (6.5% and 18%), alkaline pH (9.6), and temperatures (10 °C, 45 °C, and heat resistance at 60 °C for 30 min) was assessed. Species-level identification was carried out using the API 20 STREP gallery (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). One isolate (L11) was further confirmed by 16S rDNA sequencing, which identified it as Enterococcus faecium.

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

Antimicrobial activity of LAB isolates was evaluated using the agar well-diffusion method against a panel of indicator strains, including Listeria monocytogenes CECT4032 and CECT935, Proteus vulgaris CECT484, Pseudomonas aeruginosa CECT118, Escherichia coli CECT4076, Salmonella typhimurium CECT704, Staphylococcus aureus CECT976, and Bacillus subtilis DSMZ6633. Clear inhibition zones around the wells indicated the production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidant activity of LAB cell-free supernatants was evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay. Briefly, 1 mL of each supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of 0.2 mM DPPH solution prepared in methanol and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The decrease in absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Methanol served as the blank, and ascorbic acid was used as the positive control. The scavenging activity (%) was calculated as:

Scavenging activity (%) = [1 − Asample/Acontrol] × 100

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05) to determine significant differences among isolates. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antimicrobial Properties of Isolates

Out of the 56 presumptive LAB isolates recovered from low-sodium fermentations, eight LAB isolates exhibited notable antimicrobial activity against a range of indicator pathogens under standard growth conditions (Table 1). The inhibition zones observed exceeded 10 mm for most isolates against Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, demonstrating a broad antagonistic spectrum. The inhibitory effect is attributed primarily to the production of bacteriocin-like substances and organic acids, which collectively suppress foodborne pathogens. Comparable antimicrobial profiles have been reported in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc mesenteroides isolated from African and Asian fermented foods, emphasizing the widespread occurrence of LAB-mediated preservation mechanisms [9,10].

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity * of LAB isolates against pathogenic strains.

3.2. Morphological and Biochemical Characterization of LAB Isolates

Eight LAB isolates (L2, L3, L4, L10, L11, L15, L16, and L20) were obtained from fermented vegetables. All isolates were Gram-positive, catalase-negative cocci occurring in pairs or short chains. They exhibited high tolerance to 6.5% and 18% NaCl, alkaline pH (9.6), and elevated temperatures (45 °C and 60 °C for 30 min), demonstrating their robustness under the stress conditions typical of vegetable fermentations.

Based on API 20 STREP profiling, isolates L15 and L20 were identified as belonging to the genera Lactococcus and Leuconostoc, respectively, while L2, L3, L4, L10, L11, and L16 were assigned to the Enterococcus faecium group. Molecular analysis of the representative isolate L11 by 16S rDNA sequencing confirmed its identity as Enterococcus faecium.

The detection of E. faecium agrees with the findings of Okoye et al. [6], who reported similar strains in fermented vegetables exhibiting strong acid tolerance and efficient organic acid metabolism. The co-occurrence of Leuconostoc and Lactococcus supports previous observations that these genera dominate the early and intermediate stages of vegetable fermentation, driving acidification and enhancing product stability. Notably, Lactococcus lactis displayed superior acidification and antioxidant capacity, consistent with Akbar and Anal [5], who described its broad probiotic and antimicrobial potential in fermented foods. Together, these LAB populations likely establish a synergistic microbial consortium that contributes to both the safety and functional quality of the fermented vegetables.

3.3. Physiological Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria

The physiological evaluation of the selected LAB isolates (Table 2) was conducted to assess their adaptability under different environmental conditions. Growth at 10 °C and 45 °C, along with thermoresistance assays at 60 °C for 30 min, allowed differentiation between mesophilic and thermophilic phenotypes, following Badis et al. [9]. All isolates demonstrated growth at both 10 °C and 45 °C and retained viability after heat exposure, indicating high thermal robustness.

Table 2.

Physiological characteristics of LAB isolates demonstrating adaptability to temperature, NaCl, and pH stress conditions.

All isolates tolerated up to 6.5% NaCl, confirming halotolerance typical of LAB, while inhibition occurred at 18% NaCl. Most isolates also grew at pH 9.6, indicating resilience to mildly alkaline environments. These findings confirm that the selected LAB possess strong adaptability to thermal and osmotic stress, supporting their suitability for low-sodium fermentations.

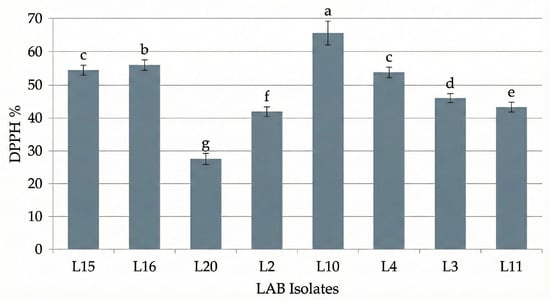

3.4. Antioxidant Activity and Functional Potential

The antioxidant performance of the eight LAB isolates is shown in Figure 1, where strain L10 exhibited the highest DPPH radical scavenging percentage, while L15 and L4 showed comparable antioxidant levels (p > 0.05), indicating similar redox performance. The DPPH radical scavenging activity observed (27–65%) indicates substantial antioxidant capacity, comparable to LAB-fermented functional foods reported in recent studies [3,11]. LAB antioxidant potential is mainly linked to the production of phenolic compounds, bioactive peptides, and exopolysaccharides (EPS), which neutralize reactive oxygen species. Guérin et al. [3] noted that EPS also enhance textural stability and support gut microbiota modulation, while Serna-Barrera et al. [4] demonstrated that LAB fermentation increases phenolic bioavailability and redox balance in plant substrates.

Figure 1.

Antioxidant activity (DPPH radical scavenging %) of LAB isolates. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation ((n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the isolates.

These findings demonstrate that Moroccan LAB isolates exhibit comparable antioxidant and adaptive metabolic capacities to well-characterized strains from other fermented foods, underscoring their potential for use in functional low-sodium formulation.

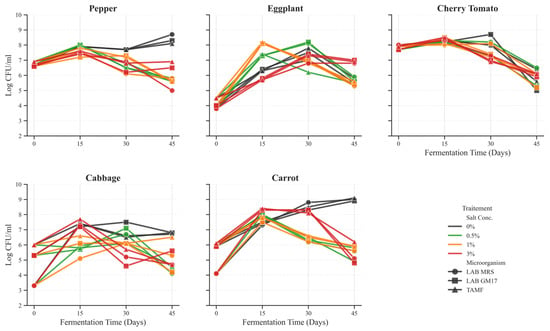

3.5. Dynamics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Total Microbial Populations

The population dynamics of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were monitored to confirm that fermentation proceeded primarily under LAB-driven conditions at reduced NaCl concentrations. LAB populations (enumerated on MRS and M17 agar) dominated the microbial ecosystem during early fermentation, showing exponential growth from day 0 to day 15, followed by a phase of relative stability for the remainder of fermentation. TAMF followed a similar trend but remained consistently lower in density, confirming LAB’s competitive dominance (Figure 2). These results align with Lee et al. [10], who reported comparable LAB-associated dynamics in vegetable fermentations.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of microbial population dynamics during the spontaneous fermentation of five vegetable matrices under varying NaCl concentrations. Data points represent the mean Log CFU/mL ± SD (n = 3). Lines are colored according to salt concentration (0% control to 3%), and markers distinguish microbial groups (● Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) cultured on MRS, ■ LAB cultured on GM17, ▲ Total Aerobic Mesophilic Flora (TAMF)).

The salt concentration played a decisive role in microbial diversity. Moderate NaCl levels (0.5–1%) enhanced LAB proliferation, consistent with Okoye et al. [6], who demonstrated that optimized glucose and nitrogen sources improved organic acid biosynthesis in LAB. High salt (3%) reduced microbial diversity and slowed acidification, indicating an osmotic inhibition effect.

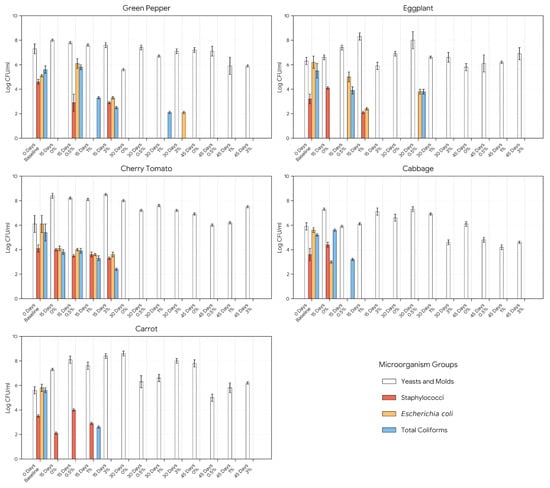

3.6. Microbial Dynamics of Spoilage and Pathogenic Populations During Fermentation

The evolution of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms across NaCl concentrations (0–3%) is shown in Figure 3. Lactic acid fermentation effectively suppressed foodborne pathogens while maintaining moderate yeast and mold levels. In all vegetable matrices, S. aureus, E. coli, and total coliforms declined rapidly, disappearing completely by 15–30 days depending on salt concentration, while yeast and mold counts stabilized or decreased after 30 to 45 days.

Figure 3.

Changes in spoilage and pathogenic microbial populations during low-sodium vegetable fermentation at varying NaCl concentrations.

These findings confirm that LAB-driven acidification and anaerobiosis inhibit pathogens effectively, while moderate salt concentrations (0.5–1%) maintain optimal microbial balance. Similar results have been reported previously [7,8,11,12,13], demonstrating that LAB fermentation ensures microbial safety through organic acid production and competitive exclusion.

3.7. Broader Industrial and Health Implications

The results of this study have strong implications for low-sodium functional food development. LAB provide a sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives, reducing chemical inputs and enhancing nutritional quality. LAB-fermented vegetables enriched with probiotic strains such as L. rhamnosus GG have been shown to improve antioxidant defenses and mitigate oxidative stress [5]. Integrating LAB fermentation into circular bioeconomy models can also valorize agricultural by-products into functional, shelf-stable foods.

From an industrial perspective, the Moroccan LAB isolates characterized here demonstrate high stress tolerance and strong biofunctional activity, making them promising candidates as starter cultures for low-sodium, plant-based fermented products.

4. Conclusions

Low-sodium vegetable fermentations represent an effective, sustainable strategy for isolating multifunctional LAB strains with both antimicrobial and antioxidant capabilities. The identification of Leuconostoc, Lactococcus, and E. faecium among the dominant isolates reinforces their potential application in functional foods and biopreservative formulations. The study’s outcomes align with recent genomic and functional studies emphasizing LAB’s role as bioactive agents in food biotechnology. Further research should explore omics-based profiling and metabolite optimization for scaling production and regulatory approval in industrial contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.E. and L.B.; methodology, L.B.; validation, F.A., and F.M.; formal analysis, M.Z. and K.B.; investigation, L.B. and K.B.; resources, F.A.; data curation, K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.E.; writing—review and editing, F.A. and M.Z.; supervision, F.A. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the European Union’s PRIMA Programme and the Moroccan Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation (MESRSI) through the Pas-Agro-Pas Project (Grant No. PRIMA/0016/2022).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achemchem, F.; Cebrián, R.; Abrini, J.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Valdivia, E.; Maqueda, M. Antimicrobial characterization and safety aspects of the bacteriocinogenic Enterococcus hirae F420 isolated from Moroccan raw goat milk. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elidrissi, A.; Ezzaky, Y.; Boussif, K.; Zanzan, M.; Bouddouch, L.; Achemchem, F. Isolation and characterization of bioprotective lactic acid bacteria from Moroccan fish and seafood. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guérin, M.; Sassi, H.; Le Blay, G. Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: Functional properties and health benefits. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 242, 116422. [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Barrera, J.; Martínez, C.; García, D. Fermentation enhances phenolic content and antioxidant activity of broccoli stem powder. Foods 2024, 13, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, A.; Anal, A.K. Lactococcus lactis: A new generation of probiotics in food systems. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Okoye, C.O.; Ohaeri, C.C.; Ezeonu, C.S. Stress tolerance and metabolic profiling of Enterococcus species isolated from fermented vegetables. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 892145. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Dominance of lactic acid bacteria during vegetable fermentation and their inhibitory role on undesirable microorganisms. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 133, 110102. [Google Scholar]

- Pino, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Caggia, C. Yeast and mold interactions in fermented vegetables: Implications for texture and product stability. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Badis, A.; Guetarni, D.; Henni, D.E. Identification and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Algerian traditional fermented products. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 623–632. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoon, J.H. Antimicrobial and functional potential of Leuconostoc mesenteroides isolated from vegetable fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 745821. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, B.; Habibi, F.; Omidbakhsh, S. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional fermented foods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. Effect of salt concentration on yeast dynamics and quality of sauerkraut fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 636–644. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Jung, M.Y. Influence of salt concentration on lactic acid fermentation kinetics and microbial diversity in kimchi. Food Control 2021, 126, 108017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.