Abstract

Microwave technology offers a sustainable alternative to fossil fuel-based drying of particulate materials. Its combination with fluidized bed systems enhances process efficiency and product quality. A pilot-scale dryer with two magnetrons was used to study soybean and pumpkin seed drying. Samples were dried at 50 °C with air velocities twice the minimum fluidization value. Microwave power levels of 0, 350, and 750 W were applied. Weight loss after 30 min reached 32.2–42.5% for soybeans and 42.0–48.2% for pumpkin seeds. Moderate microwave power improved drying efficiency, highlighting the potential of microwave-assisted fluidized bed drying for food processing sustainability.

1. Introduction

One of the most widely used dehydration methods in the food industry is hot air drying [1,2]. This type of drying can induce a series of physical changes (such as shrinkage and/or structural collapse) and chemical changes (such as the loss of vitamins and/or bioactive compounds) that may negatively affect consumer acceptability [3,4]. Therefore, the magnitude of these effects on different plant matrices remains an active area of research.

A useful alternative for fruit drying is the application of microwave (MW) technology, either as a standalone method or in combination with other techniques such as fluidization (FB). It has been demonstrated that MW application can significantly reduce drying time [5,6,7,8]. However, a common drawback is the non-uniform heating and dehydration of the product during MW drying. To overcome this issue, air fluidization combined with MW has been reported as an effective solution, as the movement of particles induced by the fluidizing air promotes uniform MW absorption [9,10]. Recently, a study on coffee drying using FB-MW reported high efficiency in terms of processing time and product quality at laboratory scale [11].

Regarding pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.), numerous studies in the literature have focused on traditional hot air drying, mainly applied to the pulp in the form of cubes [12] or slices [13,14], as well as to seeds [15]. These studies evaluated the effect of temperature (typically between 50 and 80 °C) on drying kinetics and the retention of bioactive components, finding that higher temperatures accelerate the process but simultaneously lead to a reduction in nutritional quality and organoleptic properties. Reported drying times range from 2 to 8 h, which could potentially be shortened by applying MW. To date, no studies have evaluated the use of combined fluidized bed–microwave (FB-MW) drying for pumpkin seeds.

On the other hand, soya is currently one of the most important oilseeds worldwide due to its high-quality protein content, making it a key ingredient in both human and animal diets [16]. For soybeans, some studies have been reported using combined fluidized bed and microwave drying. Anand et al. [17] investigated the effect of this combined process on vigor index, germination, fissure and cracking percentage, and seed coat hardness of dried beans. Their study provided valuable insights, although the results were obtained at a laboratory scale.

Based on the above, the objective of the present work was to study the drying kinetics and thermal histories of pumpkin seeds and soybeans using a pilot-scale FB-MW dryer, and to compare the results with those obtained from conventional fluidized bed drying (without microwaves).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Pumpkin seeds and soybeans were used for the drying experiments. The pumpkin seeds were obtained from production lines that use fresh pumpkin in their formulations (Food Plant for Social Integration, National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina), while the soybeans were purchased from local market (La Plata, Buenos Aires).

Both materials were pre-soaked for 9 h in a 1:8 (w/w) ratio with tap water at room temperature to evaluate the performance of the equipment with high-moisture matrices. After soaking, the excess water was drained, and the samples were stored in plastic containers covered with aluminum foil lids and kept under refrigeration [18].

The initial moisture content was determined by oven drying in a convective dryer (Dalvo®, Buenos Aires, Argentina), by weighing the samples [19]. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the average value was taken as the initial moisture content for all experiments.

The initial moisture content of the pumpkin seeds was 0.68 ± 0.014 (w.b.), and that of the soybeans was 0.62 ± 0.01 (w.b.).

2.2. Equipment

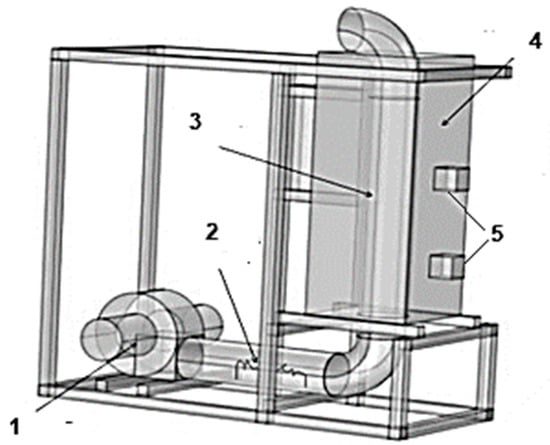

Figure 1 shows a schema of the prototype equipment built for the combined fluidized bed–microwave (FB–MW) drying process. The system consists of a drying chamber (a cylindrical tube made of plastic material) that connects the inlet and outlet grids (diameter: 0.3 m). The unit operates with preheated air, which is drawn in by a centrifugal blower (4HP, RPMControl, Buenos Aires, Argentina) located at floor level and equipped with a flow rate controller(Peakmeter, Shenzhen, China). The air is conveyed horizontally through a duct containing four electrical heating resistances inside.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the drying system: 1 fan, 2 electric resistances, 3 drying chamber, 4 resonant chamber, 5 magnetrons.

The air velocity used was 3.4 m/s for pumpkin seeds and 4.0 m/s for soybeans, corresponding to approximately twice the minimum fluidization velocity [20]. The drying air temperature was set at 50 °C.

The resonant cavity consists of a metallic enclosure containing the drying chamber. Microwave radiation is generated by two magnetrons, each with a maximum power output of 850 W, both of which can be operated independently. Different microwave power levels were selected for the experiments: 0 W corresponds to only fluidization operation (control) (Run 1), 350 W (Run 2), and 750 W (Run 3). A power of 350 W corresponds to an energy density of 0.47 W/g for pumpkin seeds and 0.35 W/g for soybeans, while 750 W corresponds to 1.0 W/g and 0.75 W/g, respectively.

For each drying experiment, approximately 750 g of soaked pumpkin seeds and 1000 g of soaked soybeans were used. During the drying process, the samples were weighed using an underload balance (Kern®, Balingen, Germany) positioned on the upper grid of the equipment. In addition, at each weighing interval, thermographic images were acquired using an infrared camera (Testo® 875i, Titisee-Neustadt, Germany) to study the temperature distribution of the materials inside the drying chamber.

From the recorded weight data, drying rate and moisture content curves were constructed as a function of time. The thermal histories were obtained from the thermographic images, processed using IRSoft software (Version 5.2, Testo®, Titisee-Neustadt).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed via Minitab (v1.9, State College, PA, USA). One-way ANOVA was applied. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drying Curves

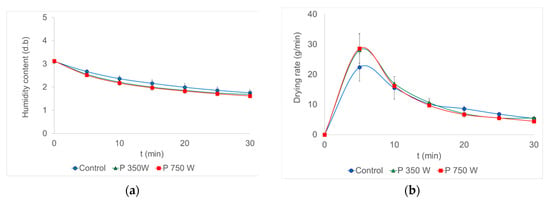

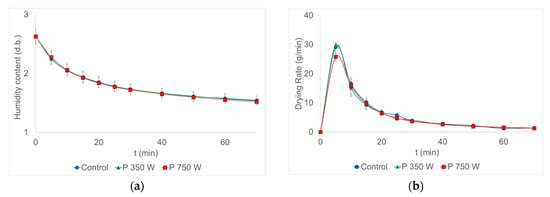

From the experiments, the drying curves and thermal histories were obtained. Figure 2a shows the drying curves for each processing condition. The statistical analysis of the drying curves revealed no significant differences among treatments for either of the two products (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, Figure 2a indicates that the application of microwaves increases the efficiency of the dehydration process in the case of pumpkin seeds. This effect is not observed in soybeans, where all curves overlap without showing any differential trend (Figure 3a).

Figure 2.

Drying curve (a) and drying rate (b) of pumpkin seeds at different operating conditions: Control (only fluidization), P 350 W (fluidization + 350 W), P 750 W (fluidization + 750 W).

Figure 3.

Drying curve (a) and drying rate (b) of soybeans at different operating conditions: Control (only fluidization), P 350 W (fluidization + 350 W), P 750 W (fluidization + 750 W).

It is important to note that the pumpkin seeds were dried with their shells and that they underwent a prior soaking step that allowed them to reach an initial moisture content of approximately 68%. A high initial moisture content induces greater interaction with microwaves. The absorption of this energy occurs volumetrically, as previously reported in the literature [11].

Drying rates can be obtained from the time derivatives of the drying curves. Figure 2b shows the drying-rate curves obtained for each operating condition in pumpkin seeds. A peak in the drying rate can be observed in all runs at 5 min of processing, followed by a decrease up to the last 30 min. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were found in the maximum drying rates between the two microwave powers, although significant differences were detected between the peaks corresponding to the combined processes and the control process. The values obtained were 24.2 g/min for the control and 28.1 and 28.6 g/min for the combined microwave–fluidization processes at 350 W and 750 W, respectively. It is worth highlighting that the peak in each curve occurs at the same processing time (5 min), although with different magnitudes. This may be attributed to the fact that water is located mainly in the shell and not in the internal part (the kernel). Moisture removal from the shell thus becomes a predominantly surface-driven rather than volumetric phenomenon. Consequently, forced-air removal is highly effective, and the application of microwaves does not cause a temporal shift in the process; instead, it only affects its intensity.

The weight-loss values of pumpkin seeds for each condition were 42.0% without microwaves, 45.8% at 350 W, and 48.2% at 750 W. The application of microwaves allowed higher drying rates to be achieved compared to the non-combined fluidization process.

Mujaffar and Ramsumair [21] reported a 24–26% weight reduction in 50 g of pumpkin seeds using air at 50 °C and air velocity of 2.39 m/s. With the equipment used in our study, we achieved a much higher weight loss in only 30 min of processing.

In the case of soybeans, the use of fluidization only and combined with microwave power at 350 W did not show significant differences, yielding a maximum of approximately 30 g/min. At the higher power level, the drying-rate curve exhibited a significantly lower maximum value (p < 0.05), indicating that increasing microwave power did not enhance the drying rate for this material.

The weight losses of soybeans were 34.15% for the fluidization treatment, 34.25% for the combined treatment with 350 W, and 34.48% for the combined treatment with 750 W. It is evident that the application of microwaves at these power levels for 1 kg of soybeans was not effective in promoting moisture removal.

Other authors have reported the effectiveness of FD–MW treatment in soybeans. Anand et al. [17] worked with 120 g of soaked soybeans with an initial moisture content of 7.02% (w.b.), using an air velocity of 7 m/s and powers up to 300 W. In that study, the authors observed an increase in drying rate due to microwave absorption at a power density of 2.5 W/g. In our case, working with 1000 g results in a maximum power density of 0.75 W/g. Such a low value does not induce the expected microwave effect and accounts for the results obtained for this material.

3.2. Thermal Histories

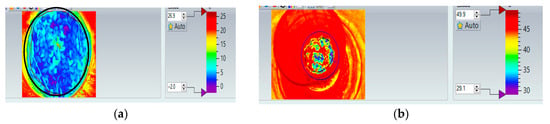

Figure 4 shows representative thermographic images acquired every 5 min, which were used to construct the thermal histories.

Figure 4.

Thermographic images obtained for the control run at the initial time (a) and after 30 min of processing (b) in pumpkin seeds.

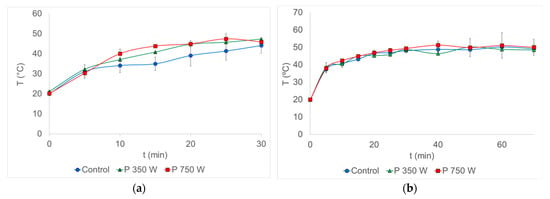

Figure 5 shows the mean values for each run for both products, while Figure 6 presents the minimum and maximum temperature values for each run (pumpkin seeds). From Figure 5a, differences in the thermal histories of pumpkin seeds can be observed (p < 0.05). The application of microwaves induces a distinct thermal behavior compared to the conventional operation. Figure 5b shows the temperature behavior for soybeans. It can be seen that the values follow the same trend regardless of the run type (p > 0.05), indicating that fluidization dominates the energy transfer mechanism over microwave absorption.

Figure 5.

Thermal histories of the analyzed conditions: (a) pumpkin seeds and (b) soybeans for the following operating conditions: Control (fluidization only), P 350 W (fluidization + 350 W), and P 750 W (fluidization + 750 W).

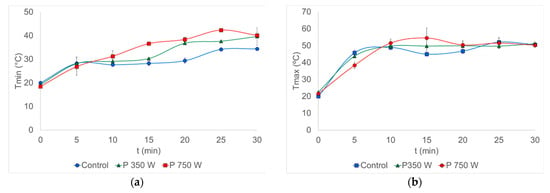

Figure 6.

Minimum (a) and maximum (b) temperature values as a function of processing time for pumpkin seeds: Control (fluidization only), P 350 W (fluidization + 350 W), and P 750 W (fluidization + 750 W).

In Figure 6a, it can be observed that the minimum temperature of the control samples remained below the curves of the combined processes for most of the time. Notably, the separation between the curves is more pronounced between 10 and 25 min of processing. For all treatments, the minimum temperature remained below the drying air temperature. It is important to emphasize that the measurements required pausing the process: every 5 min, the equipment was stopped, the upper trap was opened, weight and temperature measurements were taken, the trap was closed, and drying was resumed. Although this procedure is relatively quick, the samples may cool during the process, and since the thermographic camera measures surface temperature, this effect could be more pronounced.

Figure 6b shows the temporal evolution of the maximum temperature of pumpkin seeds. In this case, the curves overlap, and in all cases the maximum values approached the drying air temperature. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the air in regulating seed temperature, preventing overheating or scorching due to microwave application.

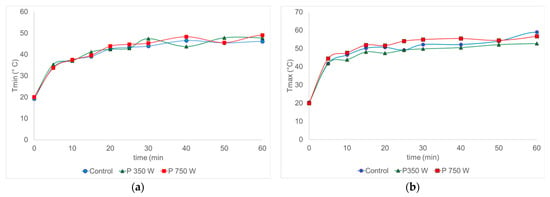

In the case of soybeans, no significant differences were observed between the minimum and maximum temperature curves (Figure 7). This again indicates that fluidization was the dominant energy transfer mechanism and that the power density was insufficient for this material to induce a temperature increase via microwave absorption within the drying chamber. To achieve a greater effect from microwave absorption, lower air velocities could be used, which might reduce the impact of fluidization and allow higher grain temperatures. Additionally, another magnetron is available, which could increase the microwave power density for the same sample load.

Figure 7.

Minimum (a) and maximum (b) temperature values as a function of processing time for soybeans: Control (fluidization only), P 350 W (fluidization + 350 W), and P 750 W (fluidization + 750 W).

4. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that the prototype fluidized-bed microwave-assisted drying system enables efficient drying of pumpkin seeds by reducing processing time and increasing the drying rate compared to conventional fluidized-bed drying. The application of microwaves enhanced weight loss during the 30-min process, reaching 45.8% and 48.2% at 350 W and 750 W, respectively, compared to 42.0% under fluidization alone.

Drying-rate curves exhibited a common peak at approximately 5 min for all operating conditions, indicating that the initial stage of drying is governed by surface moisture removal, mainly from the seed coat. Microwave application intensified this stage but did not modify its temporal occurrence. Thermal analysis based on infrared imaging showed that fluidization effectively controlled sample temperature, preventing overheating and thermal heterogeneities even when microwaves were applied. In contrast, for soybeans, the microwave power density was insufficient to produce measurable effects on either weight loss or temperature evolution.

Overall, the results indicate that convective heat transfer associated with fluidization was the dominant drying mechanism. Nevertheless, microwave incorporation accelerated dehydration, improving process efficiency without compromising thermal stability of the material. Further equipment development could be supported by improvements in the measurement system, enabling continuous acquisition of weight and temperature data without interrupting the process.

This study represents the first report on the application of FB–MW drying to pumpkin seeds and highlights its potential as a sustainable approach for the valorization of agro-industrial by-products while reducing energy-intensive processing times.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.; methodology, P.R.; formal analysis, G.S. and A.J.; investigation, P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, G.S. and A.J.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion through the Applied PICT Grant 2021-00131.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the PAIS plant (National University of La Plata, UNLP) for providing the raw materials used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ashebir, D.; Jezik, K.; Weingartemann, H.; Gretzmacher, R. Change in color and other fruit quality characteristics of tomato cultivars after hot-air drying at low final-moisture content. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Zhu, W.; Shen, C.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, J.; Cai, J. Current Status of Grain Drying Technology and Equipment Development: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-López, C.; Urrea-Garcia, G.R.; Jiménez-Fernandez, M.; Rodríguez-Jiménes, G.d.C.; Luna-Solano, G. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physicochemical and Thermal Properties of Mexican Plum (Spondias purpurea L.). CyTA—J. Food 2018, 16, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, B.; ElGasim A Yagoub, A.; Ma, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Yu, X.; Zhou, C. Role of Drying Techniques on Physical, Rehydration, Flavor, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Characteristics of Garlic. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahoor, I.; Mir, T.A.; Ayoub, W.S.; Farooq, S.; Ganaie, T.A. Recent Applications of Microwave Technology as Novel Drying of Food—Review. Food Humanit. 2023, 1, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftoonazad, N.; Dehghani, M.R.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Hybrid Microwave-Hot Air Tunnel Drying of Onion Slices: Drying Kinetics, Energy Efficiency, Product Rehydration, Color, and Flavor Characteristics. Dry. Technol. 2022, 40, 966–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.R.; Monteiro, R.L.; Laurindo, J.B.; Augusto, P.E.D. Microwave and Microwave-Vacuum Drying as Alternatives to Convective Drying in Barley Malt Processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 73, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Li, S.; Han, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, H. Study of the Drying Process of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Slices in Microwave Fluidized Bed Dryer. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1690–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohabeer, C.; Guilhaume, N.; Laurenti, D.; Schuurman, Y. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass with and without use of catalyst in a fluidised bed reactor: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salakhi, M.; Di Liddo, L.; Thomson, M.J. Modeling microwave heating in fluidized bed reactors: Revealing the interaction between microwave absorption and fluidization hydrodynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 315, 121884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Chaparro, J.; Arballo, J.R.; Campañone, L.A. Experimental Study of Parchment Coffee Drying Using the Combined Fluidization and Microwave Process: Analysis of Drying Curves and Thermal Imaging. J. Food Eng. 2024, 383, 11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, C.R.; González, A.H.; Pino, J.A.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Villavicencio, M.N. Cinética del secado e indicadores de calidad de la calabaza (Cucurbita moschata D.) deshidratación por radiación infrarroja. Rev. CENIC Cienc. Quími. 2023, 54, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- García, C.C.; Mauro, M.A.; Kimura, M. Kinetics of osmotic dehydration and air-drying of pumpkins (Cucurbita moschata). J. Food Eng. 2007, 82, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikpah, S.K.; Korese, J.K.; Sturm, B.; Hensel, O. Colour change kinetics of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) slices during convective air drying and bioactive compounds of the dried products. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Jerez, M.J.; Sánchez, A.F.; Montoya, J.E.Z. Drying kinetics and sensory characteristics of dehydrated pumpkin sedes (Cucurbita moschata) obtained by refractance window drying. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiee, S.; Keyhani, A.; Sharifi, M.; Jafari, A.; Mobli, H.; Tabatabaeefar, A. Thin Layer Drying Properties of Soybean (Viliamz cultivar). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2009, 11, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A.; Gareipy, Y.; Raghavan, V. Fluidized bed and microwave-assisted fluidized bed drying of seed grade soybean. Dry. Technol. 2020, 39, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ella, E.S.; Dionisio-Sese, M.L.; Ismail, A.M. Seed pre-treatment in rice reduces damage, enhances carbohydrate mobilization and improves emergence and seedling establishment under flooded conditions. AoB Plants 2011, 2011, plr007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 17th ed.; Horwitz, W., Ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kunii, D.; Levenspiel, O. Fluidization Engineering, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mujaffar, S.; Ramsumair, S. Fluidized Bed Drying of Pumpkin (Cucurbita sp.) Seeds. Foods 2019, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.