Abstract

Perceived time poverty is a major stress factor in university life, reflecting a lack of attentional resources. While nature-based interventions (NBIs) are recognized for restoring psychological resources, the psychological processes behind these interventions are not fully understood. This three-wave longitudinal study (N = 36) used linear mixed-effects models to examine the impact of a three-day camping trip on students’ psychological outcomes before, immediately after, and one month later. Findings show that the trip immediately and significantly boosted state nature connectedness and prosocial behavior intentions, while reducing perceived time poverty and psychological distress. Unexpectedly, it also led to a temporary decrease in both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. By one month, most benefits had returned to baseline levels. Significantly, perceived time poverty fully mediated the link between nature connectedness and most outcomes. These results suggest camping helps restore attention, but short-term NBIs can only exert a temporary effect. The study enhances scarcity and attention restoration theories by testing specific psychological pathways and targets, offering valuable insights for creating nature-based programs that reduce stress and improve experiences, especially for university wellness initiatives.

1. Introduction

Most people around the world have experienced some scarcity at some point, whether it is food, money, or time. Over the past decade, psychologists and behaviorists have focused on how resource scarcity affects people’s cognition and behavior (Griskevicius & Kenrick, 2013). In an information-rich world, the truly scarce resource is human attention (S. Kaplan, 1992). Modern university life demonstrates this, as students go through a period of growth amidst ongoing attention scarcity. Students are immersed in an environment of relentless cognitive demands, including long study hours, complex academic targets, digital overload from constant connectivity, and social and emotional challenge (Ribeiro et al., 2024). This scarcity depletes students’ cognitive resources, leading to a “scarcity mindset” characterized by the primary symptom of perceived time poverty. When cognitive bandwidth is depleted, individuals experience the subjective feeling of having too many obligations and insufficient time to meet them (De Bruijn & Antonides, 2022). A “scarcity mindset’ narrows focus to urgent tasks, often sacrificing long-term goals and overall well-being (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). It poses a threat to both individual and collective well-being, eroding happiness, reducing kindness, and potentially impeding academic and personal growth (Li et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Nature-based interventions (NBIs) are activities, programs, and strategies that offer numerous benefits, including cost-effective methods to boost overall well-being and mental and physical health through interactions with nature (Shanahan et al., 2019; Hinde et al., 2021; Pretty & Barton, 2020). Given the rising healthcare costs worldwide, these affordable interventions are especially valuable, and they are gaining recognition as an alternative approach to traditional therapies (OECD, 2024; Kaleta et al., 2025). NBIs have various types, including green exercise, such as hiking and camping, which have attracted considerable interest due to their restorative effects (R. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1983). Viewing the wilderness and nature of the destination is one important reason for Generation Z to attend hiking. They also want to refresh their mind and relieve stress and tension by embracing green exercise (Wu et al., 2022). Outdoor camping is a way to learning about nature and foster coexistence with other organisms. It serves as a lifelong activity with significant educational value for youth (Spielvogel et al., 2024). By offering an escape from everyday routines, such experiences may help restore the attentional resources, lower stress, and enhance well-being, fostering a bond and connection with nature (R. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Puhakka, 2021). This bond and connection, known as nature connectedness (NC), is an affective attachment to the natural world. It is widely regarded as a vital way that experiencing nature can bring numerous benefits to our lives (Mayer & Frantz, 2004).

While the general benefits of nature are well documented, a more nuanced understanding of these processes is still required. The duration of the beneficial effects of NBIs was unclear, as was their specific impact on certain psychological outcomes (Ibes & Forestell, 2022). Little is known about how interventions interact with psychological factors, such as time poverty, and fluctuating states, like NC. As noted by scholars, moving beyond simple pre–post designs to examine these dynamic, within-person changes over time is critical for advancing theory and practice (Spielvogel et al., 2024; Kinoshita et al., 2024). NBIs can last from mere minutes to several weeks or months. It is crucial to identify the minimum effective “dose” of NBIs, considering both duration and frequency they are applied (Wilkie & Davinson, 2021). Previous studies overlook the role of duration and frequency as important factors affecting NBI effectiveness. Establishing the minimal effective dose would be particularly valuable for educators and practitioners (Kaleta et al., 2025). Further research is necessary for planning NBIs and assessing their impact. Methodological challenges and data gaps emphasize the importance of involving diverse participants, conducting follow-up assessments, and evaluating interventions with longer durations (Silva et al., 2024). The current study aims to help fill these gaps by focusing on those that have been linked to NBI among young college adults. Using longitudinal data from a three-day camping trip, we employed linear mixed-effects modeling to address two primary research questions:

RQ1.

Did the participants’ psychological indicators (e.g., psychological distress, hedonic/eudemonic well-being, natural connectedness, perceived time poverty) and behavior intention (e.g., prosocial behavior, academic delay in gratification) change significantly over time at the within-person level?

RQ2.

Does perceived time poverty mediate the relationship between the NC and outcomes?

2. Theoretical Backgrounds and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Nature Connectedness, Nature-Based Interventions, and Mental Health

NC refers to an individual’s subjective sense of oneness with the natural world (Mayer & Frantz, 2004). It encompasses emotional, cognitive, and experiential dimensions—how people feel part of nature rather than separate from it. Importantly, NC differs from time spent in nature. It is not direct physical and/or sensory contact with the natural environment, as one may frequently visit natural settings. NC, however, reflects a psychological integration or merging of self and nature. This distinction parallels the concept of self-transcendence, where the boundaries between the self and the environment become blurred, resulting in a felt sense of unity with the natural world (Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Lengieza et al., 2021). In this study, NC is defined as the psychological joining of self and nature, experienced as a sense of oneness with the natural world.

Modern life is increasingly characterized by perceived time poverty. This sense of time scarcity has been linked to reduced well-being, lower prosocial behavior, and reduced willingness to delay gratification (Giurge et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). NBI has emerged as an effective strategy to improve mental well-being by fostering NC, restoring attention, and reducing stress (Puhakka, 2021; Bakir-Demir et al., 2021). According to Scarcity Theory, time poverty reflects a depletion of cognitive resources, especially attention, leading to a scarcity mindset. The solution is an intervention that directly targets and replenishes this specific resource. Attention restoration theory (ART) proposes that natural environments are uniquely suited to counteract directed attention fatigue. Unlike urban environments, which are filled with stimuli that demand focused attention (e.g., traffic, advertisements), nature offers “soft fascinations” (e.g., rustling leaves, moving clouds) that engage the mind effortlessly. This allows the mechanism for directed attention to rest and replenish.

Camping, as a specific form of NBI, offers immersive exposure to natural environments. It not only involves experiencing nature but also provides lasting psychological benefits by allowing people to spend extended periods immersed in a natural setting (Huang et al., 2025). Recent evidence suggests that higher NC is associated with greater psychological well-being, reduced stress, and enhanced prosocial behavior (Bakir-Demir et al., 2021; Castelo et al., 2021). The mechanism involves both affective restoration and cognitive broadening, enabling individuals to shift from a scarcity mindset to an abundant mindset (Civai et al., 2024). Exposure to natural environments can alter subjective time perception, producing a “time expansion” effect wherein time feels slower and more abundant (Droit-Volet et al., 2024). This altered temporal experience can counteract the psychological stress associated with perceived time scarcity, allowing for greater engagement in restorative and prosocial behaviors (Silva et al., 2024). Natural immersion has been shown to reduce subjective time pressure and promote a slower pace of life (Droit-Volet et al., 2024). Green exercise interventions reduce stress and restore attentional capacity, thereby indirectly alleviating perceptions of time scarcity (Silva et al., 2024).

Given its restorative and temporal effects, camping may serve as an effective intervention to mitigate time poverty and its psychological consequences (Droit-Volet et al., 2024). Multi-day nature experiences have been shown to increase NC, with effects persisting for several weeks (Silva et al., 2024). NBIs like camping are not just a generic “stress reducer”; they are targeted cognitive interventions. It aims to break the cycle of attention fatigue, thereby alleviating the scarcity mindset and its negative downstream consequences. NC influences how people engage with the environment (Martin et al., 2020). Does being in nature alter individuals’ connectedness to it? Without continued exposure, NC levels tend to regress toward baseline. Previous research suggested examining how this connection changes over time through the NBI, rather than just assessing a person’s initial level of NC (Kaleta et al., 2025). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1a.

Nature connectedness will increase after the intervention (T1 < T2), declining towards baseline after one month (T2 > T3; T3 = T1).

H1b.

Perceived time poverty will decrease after camping (T1 > T2) and remain reduced toward baseline after one month (T2 < T3; T3 = T1).

Nature exposure reduces symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress through both physiological and cognitive pathways (Bakir-Demir et al., 2021). Camping may amplify these effects by combining prolonged green exposure with social support. It can improve one’s mental health by alleviating anxiety and negative effects, such as perceived time poverty (Coventry et al., 2021). A previous study established a significant negative correlation between employees’ feelings of perceived time poverty and their well-being (Zheng et al., 2022). While this research is robust in the corporate world, the literature would benefit from a broader application to other contexts, such as students who are also highly susceptible to time pressure.

H1c.

Psychological distress will decrease after camping (T1 > T2) and remain lower for some time before returning to baseline after one month (T2 < T3; T3 = T1).

NC is a significant predictor of both hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being (Pritchard et al., 2020; Capaldi et al., 2014). Also, meta-analyses confirm that NBIs enhance both hedonic (pleasure-oriented) and eudaimonic (meaning-oriented) well-being (Silva et al., 2024). Camping’s combination of novelty, mastery, and social bonding supports both dimensions of well-being (Hassell et al., 2015). Another study, conducted one month after dragon boat racing (an outdoor river activity), found that participation is strongly connected to positive psychological factors, such as authenticity and nostalgia, and ultimately increases the overall well-being of residents in the host city (Xu et al., 2025).

H1d.

Hedonic well-being will increase after camping (T1 < T2) and remain elevated for some time before returning to baseline after one month (T2 < T3; T3 = T1).

H1e.

Eudaimonic well-being will increase after camping (T1 < T2) and remain elevated for some time before returning to baseline after one month (T2 < T3; T3 = T1).

Moreover, the influence of NC extends into the social realm. Research showed that NC can foster prosocial tendencies. Angelis and Pensini (2023) explored how personality predicts prosocial behavior. It found that NC is associated with empathy and care cultivated for the natural world. Higher NC predicts greater empathy and prosociality (Civai et al., 2024; Angelis & Pensini, 2023). Natural settings foster prosocial behavior by increasing empathy, generosity, and cooperation (Castelo et al., 2021). Also, a two-wave, time-lagged study shows that the natural environment (outdoor ski resort) and personal factors (personal ecological norm) can influence tourists’ pro-environmental behavior at the destination, and this behavior can last to spill over into daily pro-environmental actions after returning home (Yamashita et al., 2025).

H1f.

Prosocial behavior intention will increase after camping (T1 < T2), with effects retained after one month (T2 > T3; T3 = T1).

Time scarcity reduces willingness to delay rewards (Yu et al., 2024). Previous research has shown that individuals with limited resources tend to delay gratification less and prefer immediate small rewards over larger future ones (Bembenutty & Karabenick, 2004). Academic delay of gratification (ADOG) refers to students’ postponement of immediately available opportunities to satisfy impulses in favor of pursuing chosen important academic rewards or goals that are temporally remote but ostensibly more valuable (Bembenutty & Karabenick, 2004). The results of a cross-sectional survey conducted among Chinese college students revealed a negative correlation between perceived scarcity and delayed gratification (Yu et al., 2024). By alleviating perceived time poverty, camping may enhance students’ ability to postpone immediate gratification for long-term academic goals. Thus:

H1g.

Academic delay of gratification will increase after camping (T1 < T2), with partial retention after one month (T2 > T3; T3 = T1).

2.2. Perceived Time Poverty and Scarcity Theory

Perceived time poverty is a subjective psychological state that impairs cognitive performance, reduces life satisfaction, and limits future-oriented decision-making (Liu et al., 2023; Giurge et al., 2020). This experience is explained by scarcity theory, which posits that perceiving any resource as insufficient—be it time or money—narrows one’s attention to immediate concerns at the expense of long-term goals (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). Studies on financial poverty have shown that a scarcity mindset reduces mental bandwidth, encompassing cognitive capacity and executive control (De Bruijn & Antonides, 2022). Our study applies this framework to perceived time poverty, the subjective feeling of lacking enough time (Forsythe & Bailey, 1996), which similarly triggers a stress response and cognitive impairment when individuals perceive their time as a limited resource (Liu et al., 2023; Giurge et al., 2020).

For students, time poverty manifests as the subjective feeling of being overwhelmed by tasks without sufficient time to complete them (Liu et al., 2023). This perception of scarcity has significant negative consequences, impairing well-being through increased stress and anxiety (Zheng et al., 2022) and diminishing academic and social performance (Zhang et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2024). Specifically, it has been shown to reduce ADOG and prosocial intention (Zhang et al., 2023; Castelo et al., 2021). The impact on social behavior is particularly evident in fast-paced cities; for example, residents of New York and Tokyo often feel too time-pressed to help strangers, a pressure that can similarly undermine the performance and engagement of university students (Conway et al., 2021; Levine, 1988). Wladis et al. (2023) note that time poverty hampers college work and outcomes in higher education. Time poverty fully mediated the relationship between students’ online enrollment and academic performance.

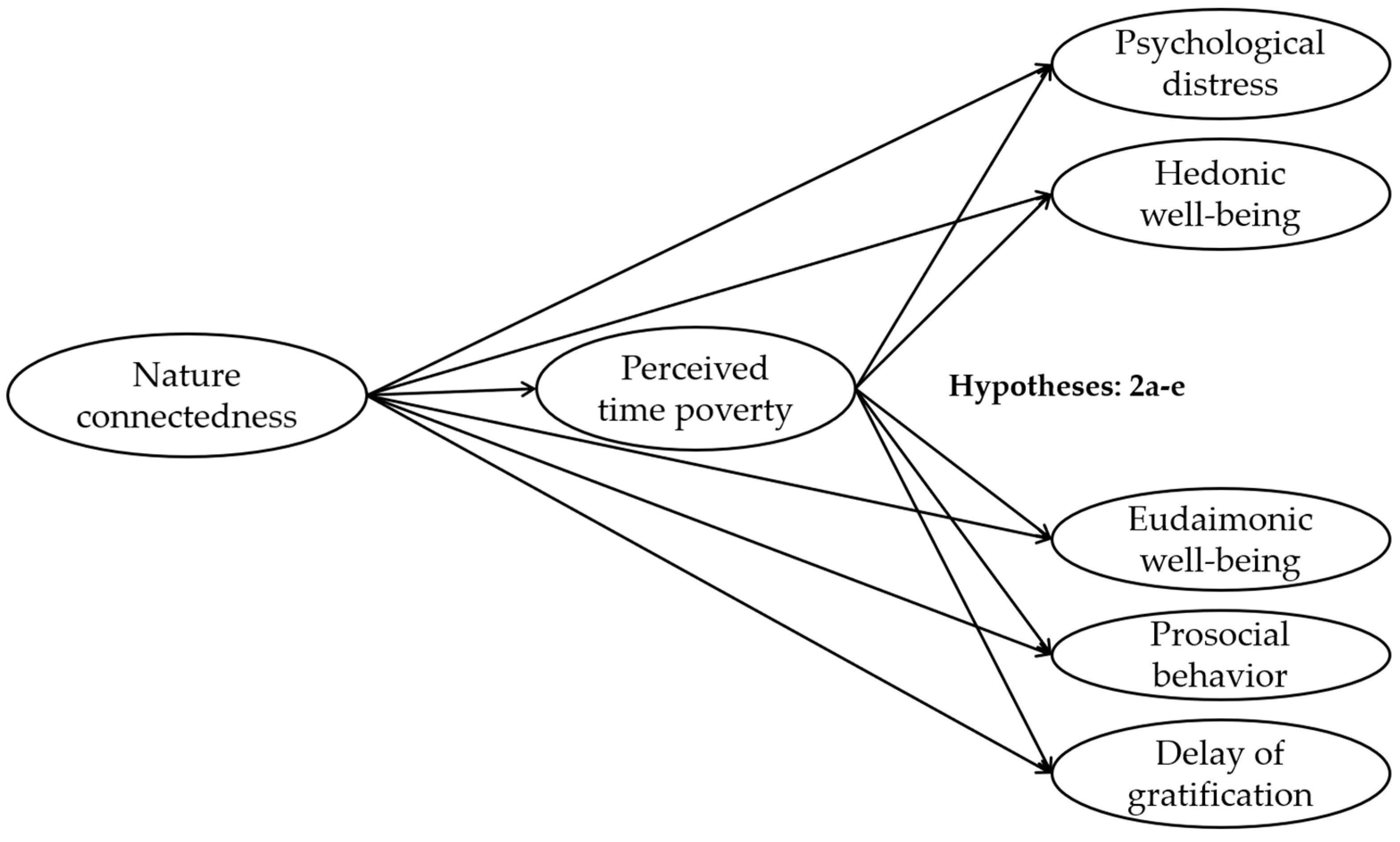

Reducing time scarcity through nature exposure enhances prosociality and future-oriented behaviors by broadening cognitive scope (Zhang et al., 2023). According to scarcity theory, perceived time poverty limits cognitive bandwidth and impairs well-being by fostering a scarcity mindset (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). Individuals who feel more connected to nature may experience greater time affluence, which can mitigate scarcity-induced stress and restore cognitive resources, thereby enhancing well-being and adaptive behaviors. Thus, we supposed that perceived time poverty can mediate the effect of NC on psychological and behavioral outcomes. A visualization of hypotheses is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptional model.

H2a–H2e.

Perceived time poverty will mediate the relationship between nature connectedness and (a) psychological distress, (b) hedonic well-being, (c) eudaimonic well-being, (d) prosocial behavior intention, and (e) academic delay of gratification.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

We collected data from undergraduate students enrolled in Sports Method Practice I ‘Camping’ at Waseda University. The course is an elective open to all undergraduate students and does not require prior camping or outdoor experience. Participation in all activities is mandatory for credit. A total of 40 students registered for the class, but only 36 students actually participated (N = 36, male = 44.44%, Mage = 19.09, SDage = 1.50). The baseline data (T1) showed that the average lifetime camping experience is 2.3 times, with most participants (75%) reporting fewer than five camping trips. The level of NC in T1 averages 3.6, indicating a moderate baseline engagement with nature. Therefore, the participants resemble a typical student population with a basic interest in outdoor activities rather than experienced nature enthusiasts. This provides a useful context for assessing changes in NC, as many participants likely had limited outdoor engagement before the course.

The camping activities took place from 29 to 31 August 2023, in Sugadaira Highland, Nagano, Japan. These camping activities aimed to foster NC and teach outdoor principles through immersion (exploring streams, waterfalls, stargazing), skill-based activities (setting up tents, outdoor cooking, fire torches), and communal activities (campfires with skits and games). These experiences not only developed practical skills but also strengthened sensory links and bonds with the natural environment.

The data were collected using an online survey, and participants could also complete the survey on paper if they were unable to access the QR code. Participants could skip any questions they did not want to answer or stop answering them entirely at any point. This study used a three-wave longitudinal design collecting data from participants. The first wave was distributed three hours before the start of camping activities (T1), serving as a baseline. The duplicate content was distributed again after the camping participation (T2), and we asked participants to respond within 48 h. Then, we collected the follow-up data one month after (T3: 30 September 2023). Researchers translated the valid scales into Japanese. Two scholars in the field of sport management were invited to check the appropriateness of the questionnaire and the wording of each item. Two additional items were embedded within the questionnaire to evaluate whether participants were paying attention. These items instructed participants to “Please select the word [a specific word] for this item.”

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Time Perception Poverty

The study employed multiple scales developed by Lesser and Forsythe (1989) to measure perceived time poverty (e.g., “I never seem to have enough time to do the things I want to do”) and by Dapkus (1985) to measure time pressure (e.g., “I often feel pressed for time”). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

3.2.2. Connectedness to Nature

The state version of the Connectedness to Nature Questionnaire (13 items) developed by Mayer et al. (2008) was used to assess the state level of nature connectedness. The scale has three dimensions: sense of unity with nature (e.g., Right now, I feel as though I belong to the earth just as much as it belongs to me), kinship with animals and plants (e.g., At this moment, I’m feeling a kinship with animals and plants), and feelings of equality between themselves and the natural world (e.g., When I think of humans’ place on earth right now, I consider them to be the most valuable species in nature) (Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Mayer et al., 2008). Two negatively worded items (numbers 4 and 12) were reversed-scored prior to further analysis. Participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.2.3. Psychological Distress

The study employed the short version K6 scale to measure psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2002) and adopted the Japanese version (Furukawa et al., 2008). This self-report scale consists of six items about symptoms of mental illness or nonspecific psychological distress: During the past 30 days, how often did you feel… (e.g., sad, nervous, restless or fidgety, hopeless, worthless). Participants rated the frequency on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“All of the time”) to 5 (“None of the time”).

3.2.4. Hedonic Well-Being

We combined the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) with the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) to create a 3-item measure assessing current, overall life satisfaction and happiness (e.g., “I am satisfied with my current life”). Participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.2.5. Eudaimonic Well-Being

Eudaimonic well-being was measured using the 6-item Psychological Well-being Scale from the short form of the Mental Health Continuum (Keyes, 2002) and the Japanese version was validated in past studies (Kinoshita et al., 2024; Sato et al., 2022) (e.g., “During the past month, how often did you feel that your life has a sense of direction or meaning to it”). The measurement employs a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always).

3.2.6. Prosocial Behavior Intentions (PBI) Scale

We used the 4-item PBI scale to assess our participants’ prosocial behavior intentions (e.g., “Comfort someone I know after they experience a hardship”) (Baumsteiger & Siegel, 2019), with two additional items that we developed based on the scale’s dimensions. Items can be categorized by: help size (small, medium, large), recipient (friend, family, acquaintance, stranger), and help cost (time, effort, resources). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely would not do this) to 7 (definitely would do this). All items were coded positively, with higher scores indicating stronger intentions.

3.2.7. Academic Delay of Gratification Scale (ADOG)

We adopted five items from ADOGS (Bembenutty & Karabenick, 1998) to measure the intention to delay gratification. All items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely choose A, 2 = Probably choose A, 3 = Probably choose B, 4 = Definitely choose B) with the statement “Choose your true beliefs rather than the option you think you should choose.” Participants need to choose one after reading the scenario (e.g., A. Miss several classes to accept an invitation for a very interesting trip, OR B. Delay going on the trip until the course is over). The points will be collected and averaged.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

To examine the longitudinal effects of the three-day camping intervention, a series of linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) was estimated. This analytical approach allows for a direct test of within-person changes across the three time points. All analyses were performed using the R software (Version 4.2.3) with the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015) for mixed modeling. For each psychological outcome, time was entered as a fixed factor with three levels (T1: pre-camp, T2: post-camp, T3: one-month follow-up), with T1 serving as the reference category. Data were structured as multilevel (i.e., in long format), with each observation representing one wave of data, and waves clustered within individuals (i.e., participants nested in three waves). Participant ID was included as a random intercept to account for stable between-person differences. These models disaggregate fixed and random effects, allowing us to compare individuals to themselves over time, as well as comparing individuals to one another.

4. Results

4.1. Pre–Post and Follow-Up Change Comparison

According to T1 results, adults (N = 36, male = 44.44%, Mage = 19.09, SDage = 1.50) from the university without mental and physical health problems were eligible for inclusion. A series of linear mixed-effects models was conducted to examine changes across three time points. The results of longitudinal changes in all outcome variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Linear Mixed-Effects Models Predicting Changes in Outcomes.

NC significantly increased from T1 to T2 (B = 0.98, p < 0.001), indicating an immediate positive effect of the intervention. However, this gain was not fully sustained, as there was a significant decrease from T2 to T3 (B = −0.64, p < 0.001). The overall change from T1 to T3 remained significant (B = 0.34, p = 0.02).

Perceived time poverty showed a significant decrease from T1 to T2 (B = −0.97, p < 0.001), followed by a significant rebound from T2 to T3 (B = 0.92, p < 0.001). The overall change from T1 to T3 was not significant (B = −0.04, p = 0.84).

Psychological distress significantly decreased from T1 to T2 (B = −0.50, p < 0.01), but this improvement was reversed with a significant increase from T2 to T3 (B = 0.36, p = 0.03). The overall change was not significant from T1 to T3.

Hedonic well-being showed no immediate change from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3, but exhibited a significant decline from T1 to T3 (B = −0.46, p = 0.04).

Eudaimonic well-being showed no immediate change from T1 to T2, but it showed a significant decrease from T2 to T3 (B = −0.40, p = 0.05). The overall change from T1 to T3 is not significant.

For prosocial behavior intention, there was a significant increase from T1 to T2 (B = 0.35, p = 0.03), which was not maintained at T3.

Finally, ADOG significantly decreased from T1 to T2 (B = −0.19, p = 0.04). Therefore, H1a was partially supported, H1b and H1c were supported, H1d was not supported, H1e and H1f were partially supported, and H1g was not supported.

4.2. Indirect Effect Analysis

Findings showed that NC’s indirect effect on psychological distress through perceived time poverty was significant (β = −0.09, SE = 0.05; CIBC = [−0.24, −0.04]), but the direct effect was not (β = 0.12, SE = 0.11, p = 0.30), indicating that perceived time poverty was fully mediated. Similarly, NC’s indirect effects on hedonic well-being significant (β = 0.08, SE = 0.05; CIBC [0.01, 0.20]), eudaimonic well-being (β = 0.12, SE = 0.06; CIBC [0.05, 0.27]), and prosocial behavior intention (β = 0.04, SE = 0.03; CIBC [0.01, 0.10]) via perceived time poverty were significant, with no significant direct effects (Hed: β = 0.01, SE = 0.17, p = 0.99; Eud: β = 0.05, SE = 0.14, p = 0.73; PBI: β = 0.21, SE = 0.12, p = 0.07), suggesting full mediation. Conversely, NC’s effect on ADOG was not mediated, as the indirect effect was not significant (β = −0.01, SE = 0.02; CIBC [−0.05, 0.02]), yet the direct impact was significant after including perceived time poverty (β = 0.13, SE = 0.07, p = 0.05). Therefore, H2a–d were supported while H2e was not supported. The results were presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Standardized estimates, SE, and 95% CIs for hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

This study examined the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between perceived time poverty and various psychological outcomes among university students, utilizing a nature-based camping intervention as a longitudinal research context. Our findings move beyond the general discussion that “time pressure is stressful” and “nature is restorative” to reveal a particular and theoretically rich story. By employing a three-wave design and linear mixed-effects modeling, we were able to capture the dynamic within-person changes that occurred as a result of the intervention. The findings showed that the camping served as a helpful and positive psychological experience, yielding significant short-term benefits for participants.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

From T1 to T2, the results show that the three-day camping trip was an effective intervention for creating immediate, positive psychological changes, which is in line with the previous research (Shanahan et al., 2019; Hinde et al., 2021; Pretty & Barton, 2020). The most apparent effects were the sharp increases in state NC and the simultaneous decreases in perceived time poverty and psychological distress after the camping (T2). This pattern strongly supports the ART (R. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). By immersing students in a natural setting, it offers a break from ongoing cognitive demands, allowing their limited capacity for focused attention to be restored.

The rise in prosocial behavior intention (T2) suggests that resource restoration broadens mental scope, enabling greater consideration of others, which is consistent with previous research (Castelo et al., 2021; Civai et al., 2024). The group-based nature of the camping experience may have fostered a greater sense of community and altruism. Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being did not have significant results at T2, which is inconsistent with previous research (Pritchard et al., 2020; Capaldi et al., 2014) due to the data collection point or duration of the intervention (Silva et al., 2024). ADOG level has decreased due to the transition from a supportive environment to a stressful routine, which can cause temporary negative effects. The overwhelming feeling of returning to a mountain of responsibilities can crush motivation, leading students to favor immediate comforts over long-term academic goals, resulting in decreased academic drive and motivation (Liu et al., 2023; Bembenutty & Karabenick, 2004; Giurge et al., 2020).

In the month after the intervention (T3), if participants were without ongoing exposure to the restorative environment, the initial benefits mostly faded away. Only the increase in NC was sustained at T3, suggesting that a deep sense of connection to nature may be a more durable psychological resource. The significant reductions in time poverty and distress, as well as the increases in prosocial behavior intention, were no longer statistically significant at the one-month follow-up (T3). This is a predictable effect, as students are preparing for the new semester when we collect the T3 data. Unexpectedly, hedonic and eudaimonic well-being decreased. The sudden drop from the “high” of the camping trip to the “low” of routine academic life manifests as a temporary decline in happiness (hedonic well-being) and sense of purpose (eudaimonic well-being). The more effective and transformative a restorative experience is, the greater the potential for a difficult return.

This finding does not undermine the value of the NBI; rather, it identifies a previously under-theorized and critical component of the intervention process itself: the transition home. The positive impacts of an intervention diminish or disappear over time once the intervention itself is removed (Bailey et al., 2020). The students returned to an academic environment that was fundamentally unchanged, which is highly cognitively demanding and attention-scarce. It suggests that while short and intensive nature experiences are highly effective for immediate psychological “resets,” their benefits may not persist without continued engagement or subsequent “doses” of similar experiences. This aligns with ART (R. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989), which posits that a change of scenery and the experience of “being away” are primary mechanisms for stress reduction. Sustained improvements in well-being likely require sustained or repeated engagement with nature. Longer-term or repeated nature encounters are needed to produce more durable changes in psychological health (Choe et al., 2025).

The finding showed that perceived time poverty fully mediated the relationship between NC and most outcomes (distress, well-being, and prosocial behavior intention). Immersion in nature enhances the state NC, which restores the finite resource of directed attention. The replenishment of this scarce cognitive resource alleviates the feeling of attention scarcity, which is experienced subjectively as reduced perceived time poverty. When individuals experience a stronger NC, they tend to feel less “time-poor” or rushed (Droit-Volet et al., 2024). This altered perception of having more time appears to be a crucial psychological resource that enables positive outcomes to emerge. With more perceived time, the cognitive burden of stress is lessened (lower distress), there is more mental space to experience happiness and meaning (higher well-being), and there is greater cognitive capacity to think beyond oneself and foster a greater willingness to engage in prosocial behaviors (higher prosociality) (Civai et al., 2024). The non-significant direct effects in the mediation models are crucial evidence, suggesting that without a change in time perception, the link between NC and these outcomes is substantially weakened. The non-significant mediation for ADOG suggests that academic motivation is a more complex, goal-oriented cognitive function. While NC may influence it, it does not appear to operate through the broad affective channel of perceived time poverty.

This study advances NBI research by showing that the benefits of deep nature immersion may extend beyond ART to include the reshaping of subjective temporal experience. In line with prior evidence that NBIs alleviate stress and distress by enhancing NC and reducing perceived scarcity (Spielvogel et al., 2024; Puhakka, 2021), our findings highlight perceived time poverty as a novel mechanism that mediates the relationship between NC and key outcomes. While other research suggests that even brief, repeated “micro-doses” of nature can produce sustainable gains (Ibes & Forestell, 2022), our work provides a potential explanation for why this might be so: by fostering a deeper sense of NC that, in turn, alters time perception. Taken together, this work positions immersive NBIs not only as restorative experiences but also as powerful strategies that transform perceptions of time, thereby unlocking the psychological resources essential.

5.2. Practical Implications

For individuals experiencing high stress and feelings of being constantly rushed, the results suggest that actively fostering an NC could be a tangible and effective strategy. Rather than just spending time in nature, NC differs by representing a psychological integration or merging of self with the natural environment, not merely physical or sensory contact. It is about a deeper connection, beyond frequent visits to natural settings. The goal is not just to “relax,” but to fundamentally alter one’s perception of time, which in turn boosts well-being (Bakir-Demir et al., 2021; Castelo et al., 2021). On a personal level, the study offers a simple, evidence-based directive for navigating the pressures of modern life: to find more time, we may first need to reconnect with nature. For organizations and universities, these findings highlight the value of promoting immersive green experiences. To combat burnout, interventions could go beyond recommending simple “green breaks” and instead include structured opportunities that are explicitly designed to facilitate and deepen a subjective sense of NC, as this appears to be the key factor for changing the perception of time and fostering lasting benefits. For example, guided nature walks, group camping trips, or workshops on local ecology could be more effective than simply pointing to a nearby park.

While this study provides clear guidance and calls back with previous research that intensive, multi-day NBIs can be a highly effective tool for immediate stress reduction (Puhakka, 2021; Bakir-Demir et al., 2021), the temporary nature of these effects suggests that a “one-and-done” approach is insufficient (Wilkie & Davinson, 2021). To cultivate deeper outcomes, such as eudaimonia and self-regulation (ADOG), the design of university wellness programs must go further. It is not enough to simply bring students into nature; practitioners should incorporate activities explicitly designed to facilitate and deepen a subjective sense of NC for fostering lasting benefits. Institutions should consider offering regular and accessible nature-based leisure activities throughout the academic year to reinforce the initial benefits and promote sustained well-being. These programs can be powerfully deployed during high-stress periods, such as midterms or finals, to provide students with a much-needed psychological reset.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The study was conducted with a modest sample size and without a non-intervention control group, which limits our ability to make definitive causal claims and generalize the findings broadly. Future research should aim to replicate these findings with a larger sample and a randomized controlled trial design (Silva et al., 2024). Furthermore, our results point to the importance of “dosage.” Future studies should systematically investigate how the duration, frequency, and intensity of nature-based interventions influence the magnitude and durability of their psychological benefits. For instance, does a 30 min daily walk with a focus on fostering connectedness yield similar changes in time perception as a single, multi-day immersive trip? Finally, exploring the specific programmatic elements (e.g., group activities vs. solo reflection) that most effectively boost state NC would be a valuable avenue for future inquiry.

6. Conclusions

This three-wave study demonstrates that a short, immersive camping trip provides significant and immediate psychological benefits to university students, primarily by alleviating perceived time poverty. While many of these effects are temporary, the findings powerfully underscore the value of NBIs as a potent tool for psychological restoration and positive functioning. The study enhances scarcity and attention restoration theories, providing valuable insights for developing university wellness programs that not only restore attention but also support students during the challenging transition back to demanding academic settings. This study explored how outcomes change over three time points. To understand the underlying mechanism, the mediator of perceived time poverty can explain the changes in an individual’s NC and psychological outcomes over time. For a student population struggling with the pressures of time poverty, such experiences are not merely a fun experience, but a vital resource for maintaining a healthy and balanced life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and S.S.; methodology, Y.W. and S.S.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and S.S.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists [Grant Number 23K16732].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Waseda University (No. 2022-286, 27 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to all participants for their cooperation, to Fumitake Matsushima and Torill Olsen for data collection, and to Kinoshita for his advice on this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NC | Nature connectedness |

| ADOG | Academic delay of gratification |

| NBIs | Nature-based intervention |

| LMM | Linear mixed-effects models |

References

- Angelis, S., & Pensini, P. (2023). Honesty-humility predicts humanitarian prosocial behavior via social connectedness: A parallel mediation examining connectedness to community, nation, humanity, and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(6), 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Cunha, F., Foorman, B. R., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: Mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 21(2), 55–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir-Demir, T., Berument, S. K., & Akkaya, S. (2021). Nature connectedness boosts the bright side of emotion regulation, which in turn reduces stress. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumsteiger, R., & Siegel, J. T. (2019). Measuring prosociality: The development of a prosocial behavioral intentions scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(3), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (1998). Academic delay of gratification. Learning and Individual Differences, 10(4), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (2004). Inherent association between academic delay of gratification, future time perspective, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L., & Zelenski, J. M. (2014). The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N., White, K., & Goode, M. R. (2021). Nature promotes self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., Yu, Y., Wang, Y., & Zheng, L. (2023). Influences of mental accounting on consumption decisions: Asymmetric effect of a scarcity mindset. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1162916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, E. Y., Lee, J. Y., & Zhu, S. (2025). Exploring the dose-response relationship between nature-based outdoor activities, nature connectedness and social health in adolescents: A quasi-experimental controlled study. Journal of Adolescence, 97(4), 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civai, C., Elbaek, C. T., & Capraro, V. (2024). Why scarcity can both increase and decrease prosocial behaviour: A review and theoretical framework for the complex relationship between scarcity and prosociality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 60, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, K. M., Wladis, C., & Hachey, A. C. (2021). Time poverty and parenthood: Who has time for college? AERA Open, 7, 233285842110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P. A., Brown, J. E., Pervin, J., Brabyn, S., Pateman, R., Breedvelt, J., Gilbody, S., Stancliffe, R., McEachan, R., & White, P. L. (2021). Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM—Population Health, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dapkus, M. A. (1985). A thematic analysis of the experience of time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(2), 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, E. J., & Antonides, G. (2022). Poverty and economic decision making: A review of scarcity theory. Theory and Decision, 92, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S., Miot, S., & Chaulet, M. (2024). Awe and time perception. Acta Psychologica, 244, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, S. M., & Bailey, A. W. (1996). Shopping enjoyment, perceived time poverty, and time spent shopping. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 14(3), 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T. A., Kawakami, N., Saitoh, M., Ono, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y., Tachimori, H., Iwata, N., Uda, H., Nakane, H., Watanabe, M., Naganuma, Y., Hata, Y., Kobayashi, M., Miyake, Y., Takeshima, T., & Kikkawa, T. (2008). The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurge, L. M., Whillans, A. V., & West, C. (2020). Why time poverty matters for individuals, organisations and nations. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V., & Kenrick, D. T. (2013). Fundamental motives: How evolutionary needs influence consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(3), 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassell, S., Moore, S. A., & Macbeth, J. (2015). Exploring the motivations, experiences and meanings of camping in national parks. Leisure Sciences, 37(3), 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, S., Bojke, L., & Coventry, P. (2021). The cost effectiveness of ecotherapy as a healthcare intervention, separating the wood from the trees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Liu, C., & Hung, K. (2025). Understanding camping tourism experiences through thematic analysis: An embodiment perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 56(5), 660–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D. C., & Forestell, C. A. (2022). The role of campus greenspace and meditation on college students’ mood disturbance. Journal of American College Health, 70(1), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleta, B., Campbell, S., O’keeffe, J., & Burke, J. (2025). Nature-based interventions: A systematic review of reviews. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1625294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. (1992). The restorative environment: Nature and human experience. Timber Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, K., Usami, S., & Matsuoka, H. (2024). Perceived event impacts of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games on residents’ eudaimonic well-being: A longitudinal study of within-person changes and relationships. Sport Management Review, 27(3), 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M. L., Swim, J. K., & Hunt, C. A. (2021). Effects of post-trip eudaimonic reflections on affect, self-transcendence and philanthropy. The Service Industries Journal, 41(15–16), 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, J. A., & Forsythe, S. M. (1989). Antecedents and consequences of the intrinsic motivation to shop. Psychological Reports, 64(3c), 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R. V. (1988). Measuring the silent language of time. In P. A. Bronstein, & K. Quina (Eds.), Teaching about culture, ethnicity, and diversity (pp. 29–34). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., Yu, W., Hu, X., & Jin, L. (2024). The impact of subjective social class on subjective well-being: Examining the mediating roles of perceived scarcity and sense of control. Current Psychology, 43, 27327–27338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Yang, X., Meng, F., & Wang, Q. (2023). Teachers who are stuck in time: Development and validation of teachers’ time poverty scale. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 2267–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L., White, M. P., Hunt, A., Richardson, M., Pahl, S., & Burt, J. (2020). Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F. S., Frantz, C. M., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Dolliver, K. (2008). Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature: The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Decision making and policy in contexts of poverty. In E. Shafir (Ed.), Behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 281–300). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2024). Fiscal sustainability of health systems: How to finance more resilient health systems when money is tight? OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J., & Barton, J. (2020). Nature-based interventions and mind–body interventions: Saving public health costs whilst increasing life satisfaction and happiness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R. (2021). University students’ participation in outdoor recreation and the perceived well-being effects of nature. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 36, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H., Santana, K. V. D. S., & Oliver, S. L. (2024). Natural environments in university campuses and students’ well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S., Kinoshita, K., Kim, M., Oshimi, D., & Harada, M. (2022). The effect of Rugby World Cup 2019 on residents’ psychological well-being: A mediating role of psychological capital. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(5), 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D. F., Astell–Burt, T., Barber, E. A., Brymer, E., Cox, D. T. C., Dean, J., Depledge, M., Fuller, R. A., Hartig, T., Irvine, K. N., Jones, A., Kikillus, H., Lovell, R., Mitchell, R., Niemelä, J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Pretty, J., Townsend, M., van Heezik, Y., … Gaston, K. J. (2019). Nature-based interventions for improving health and wellbeing: The purpose, the people and the outcomes. Sports, 7(6), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A., Matos, M., & Gonçalves, M. (2024). Nature and human well-being: A systematic review of empirical evidence from nature-based interventions. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67(12), 3397–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielvogel, B., Lubeznik-Warner, R. P., Sibthorp, J., & Browne, L. P. (2024). A national longitudinal study examining social-emotional benefits of summer camp for early adolescents: Effects of attendance, dosage, and experience quality. Journal of Leisure Research. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In I. Altman, & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Behavior and the natural environment (pp. 85–125). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, S., & Davinson, N. (2021). Prevalence and effectiveness of nature-based interventions to impact adult health-related behaviours and outcomes: A scoping review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 214, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wladis, C., Hachey, A. C., & Conway, K. (2023). Time poverty: A hidden factor connecting online enrollment and college outcomes? The Journal of Higher Education, 94(5), 609–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Kinoshita, K., Zhang, Y., Kagami, R., & Sato, S. (2022). Influence of COVID-19 crisis on motivation and hiking intention of Gen Z in China: Perceived risk and coping appraisal as moderators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Wu, Y., Zhang, Y., Kinoshita, K., & Sato, S. (2025). Investigating the psychological benefits of authentic sport event: The case of dragon boat races. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R., Wu, Y., & Sato, S. (2025). How sport tourism experience influences daily pro-environmental behaviour: The role of eco-friendly reputation and personal norm. Tourism Recreation Research, 50(4), 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Gao, J., Kong, Y., & Huang, L. (2024). Impact of perceived scarcity on delay of gratification: Meditation effects of self-efficacy and self-control. Current Psychology, 43, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Yuan, Z., & Li, C. (2023). Prosocial decision-making under time pressure: Behavioral and neural mechanisms. Human Brain Mapping, 44(17), 6090–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., Zhang, Q., Li, X., & Wu, B. (2022). Being busy, feeling poor: The scale development and validation of perceived time poverty. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 30(4), 596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).