Validation of the Positive Eating Scale in Chinese University Students and Its Associations with Mental Health and Eating Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation and Cultural Adaptation

2.2. Study Population and Sampling Methods

2.3. Reliability Assessment

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Collection Methods

2.6. Measurement Tools

2.6.1. Original Scale

2.6.2. Anxiety and Depression Questionnaires

2.6.3. Dietary Survey

2.6.4. Date Cleaning

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Validation of the Validity of PES-C

Model Construction and Model Fit Indices

3.3. Reliability Analysis of PES-C

3.3.1. Internal Consistency, Test-Retest Reliability, Split-Half Reliability and Inter-Item and Item-Total Correlations

3.3.2. Measurement Invariance Analysis of PES-C Across Gender and Ethnicity

3.4. PES-C Scores Across Demographic Variables

3.5. Correlation Analysis of PES-C Total Score and Dimension Score with PHQ-9, GAD-7 and Dietary Intake Frequency

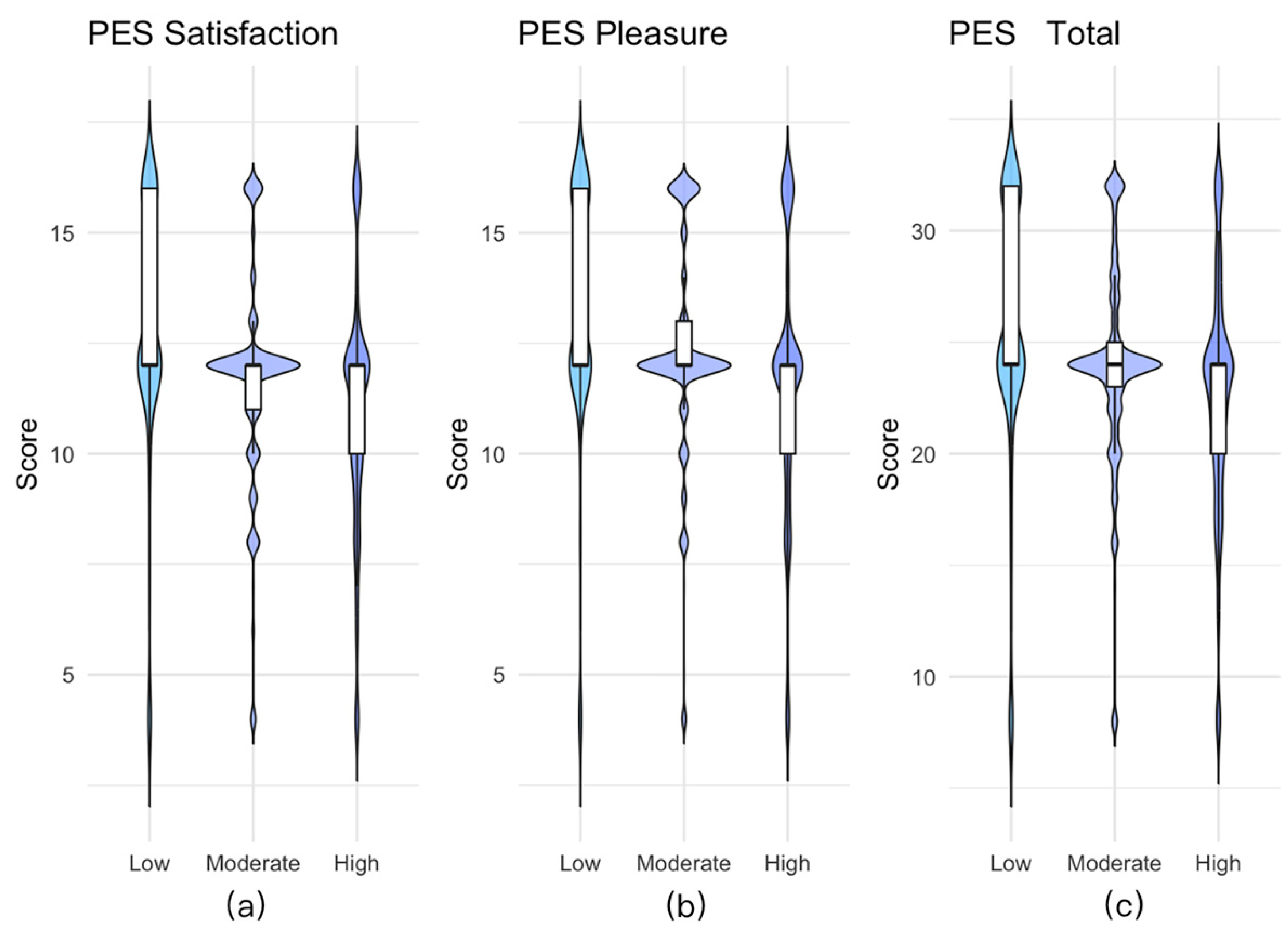

3.6. Distribution Characteristics of PES-C Scores Across Different Levels of Anxiety and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PES | Positive Eating Scale |

| PES-C | the Chinese version of the Positive Eating Scale |

| SSBs | sugar-sweetened beverages |

| RCS | Restricted cubic spline |

References

- Acik, M., & Aslan Cin, N. N. (2025). Links between intuitive and mindful eating and mood: Do food intake and exercise mediate this association? Frontiers in Nutrition, 12, 1458082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizri, M., Geagea, L., Kobeissy, F., & Talih, F. (2020). Prevalence of eating disorders among medical students in a Lebanese medical school: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Onieva-Zafra, M. D., Parra-Fernandez, M. L., Staniszewska, A., Modrzejewska, J., & Fernandez-Martinez, E. (2020). Evaluation of orthorexia nervosa and symptomatology associated with eating disorders among European university students: A multicentre cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 12(12), 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., Lin, L., Dai, M., Chen, Y., Li, X., Ma, J., & Jing, J. (2018). One-child policy, weight status, lifestyles and parental concerns in Chinese children: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(8), 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. H., & Lee, H. (2020). Associations of mindful eating with dietary intake pattern, occupational stress, and mental well-being among clinical nurses. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 56(2), 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P., López-Franco, M. D., Capelas, M. L., Almeida, S., Bennett, P. M., da Silva, M. M., Teixeira, G., Nunes, E., Lucas, P., Gaspar, F., & Handovers4SafeCare. (2024). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: A practical guideline for novice researchers. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, K. M., & Byrd-Bredbenner, C. (2021). Disordered eating concerns, behaviors, and severity in young adults clustered by anxiety and depression. Brain and Behavior, 11(12), e2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felske, A. N., Williamson, T. M., Rash, J. A., Telfer, J. A., Toivonen, K. I., & Campbell, T. (2022). Proof of concept for a mindfulness-informed intervention for eating disorder symptoms, self-efficacy, and emotion regulation among bariatric surgery candidates. Behavioral Medicine, 48(3), 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J., Gangwisch, J. E., Borisini, A., Wootton, R. E., & Mayer, E. A. (2020). Food and mood: How do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ, 369, m2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H. L., & García, L. (2025). Intuitive eating and its associations with psychological and physical health indicators among rural US adults. Journal of Health Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T., & Forestell, C. A. (2021). Mindfulness, mood, and food: The mediating role of positive affect. Appetite, 158, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling—A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. J., Egan, S. J., Howell, J. A., Hoiles, K. J., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2020). An examination of the transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural model of eating disorders in adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 39, 101445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. W., Stewart, S. M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Lee, S., Ho, S. Y., Lee, P. W. H., Katzman, M. A., & Lam, T. H. (2007). Validation of the eating disorder diagnostic scale for use with Hong Kong adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(6), 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Z., Zhao, Z. Y., Chen, D. J., Peng, Y., & Lu, Z. X. (2022). Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(11), 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Braakhuis, A., Li, Z., & Roy, R. (2022). How does the university food environment impact student dietary behaviors? A systematic review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 840818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhang, Y. T., Huang, Z. J., Chen, X. L., Yuan, F. H., & Sun, X. J. (2019). Diminished anticipatory and consummatory pleasure in dysphoria: Evidence from an experience sampling study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. M., Yang, Q. P., Luo, J., Ouyang, Y. F., Sun, M. H., Xi, Y., Yong, C. T., Xiang, C. H., & Lin, Q. (2020). Association between emotional eating, depressive symptoms and laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms in college students: A cross-sectional study in Hunan. Nutrients, 12(6), 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, B., Decker, O., Muller, S., Brahler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macht, M. (2008). How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite, 50(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquis, M., Talbot, A., Sabourin, A., & Riopel, C. (2018). Exploring the environmental, personal and behavioural factors as determinants for university students’ food behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(1), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, G. L. R., Santo, R. E., Mas Clavel, E., Bosque Prous, M., Koehler, K., Vidal-Alaball, J., van der Waerden, J., Gobina, I., Lopez-Gil, J. F., Lima, R., & Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. (2025). Digital dietary interventions for healthy adolescents: A systematic review of behavior change techniques, engagement strategies, and adherence. Clinical Nutrition, 45, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D., Ma, Z., Villasenor, D., Odegaard, A., Lu, Y., & Lindsay, K. (2025). Easy-to-learn dietary behavior change intervention does not significantly improve diet quality of college students: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition Research, 140, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyfung, P., Petchoo, J., & Chaisit, S. (2025). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risk of visceral fat accumulation among university students in Thailand. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny, 76(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q., Sun, Q., Yang, L., Cui, Y., Du, J., & Liu, H. (2023). High nutrition literacy linked with low frequency of take-out food consumption in chinese college students. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, L. A., & Brown, T. A. (2017). Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 (GAD-7) in outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39(1), 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski-Bednarz, S. B., Hillert, A., Surzykiewicz, J., Riedl, E., Harder, J. P., Hillert, S. M., Adamczyk, M., Uram, P., Konaszewski, K., Rydygel, M., Maier, K., & Dobrakowski, P. (2024). Longitudinal impact of disordered eating attitudes on depression, anxiety, and somatization in young women with anorexia and bulimia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(17), 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproesser, G., Klusmann, V., Ruby, M. B., Arbit, N., Rozin, P., Schupp, H. T., & Renner, B. (2018). The positive eating scale: Relationship with objective health parameters and validity in Germany, the USA and India. Psychology & Health, 33(3), 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, G. A., Moraes, J. M. M., Carvalho, P. H. B., & Alvarenga, M. D. S. (2025). Adaptação transcultural e avaliação das propriedades psicométricas da versão brasileira da Positive Eating Scale [Cross-cultural adaptation and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Positive Eating Scale]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 30(4), e13322023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T. L., Maiano, C., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Linardon, J., Burnette, C. B., Todd, J., & Swami, V. (2024). The Intuitive Eating Scale-3: Development and psychometric evaluation. Appetite, 199, 107407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J. M., Smith, N., & Ashwell, M. (2017). A structured literature review on the role of mindfulness, mindful eating and intuitive eating in changing eating behaviours: Effectiveness and associated potential mechanisms. Nutrition Research Reviews, 30(2), 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Mata, J., Furman, D. J., Whitmer, A. J., Gotlib, I. H., & Thompson, R. J. (2017). Anticipatory and consummatory pleasure and displeasure in major depressive disorder: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(2), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Gao, Z. J., Yu, X., & Wang, P. (2022). Dietary regulation in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7(1), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Yang, Z., Liu, D., Yu, C., Zhao, Y., Yang, J., Su, Y., Jiang, Y., & Lu, Q. (2023). Mediating effect of physical sub-health in the association of sugar-sweetened beverages consumption with depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: A structural equation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 342, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. M., Su, H. D., & Li, C. L. (2022). Effect of body dissatisfaction on binge eating behavior of Chinese university students: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 995301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Cui, Y., Gong, Q., Huang, C., Guo, F., Li, W., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Cheng, X., & Wang, Y. (2019). Frequency of breakfast consumption is inversely associated with the risk of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e0222014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content | Sample Size (Percentage) | Total Score | Dietary Satisfaction | Dietary Pleasure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1040 (55.3) | 25.239 ± 5.540 | 12.520 ± 2.871 | 12.720 ± 2.922 |

| Female | 842 (44.7) | 24.464 ± 5.258 | 11.860 ± 2.828 | 12.610 ± 2.828 |

| t | 3.013 | 5.012 | 0.854 | |

| p | 0.008 ** | 0.024 * | 0.091 | |

| Grade | ||||

| Freshman | 863 (45.9) | 25.096 ± 5.513 | 12.330 ± 2.917 | 12.760 ± 2.881 |

| Sophomore | 603 (32.0) | 24.801 ± 5.597 | 12.170 ± 2.917 | 12.630 ± 3.006 |

| Junior | 312 (16.6) | 24.513 ± 5.036 | 12.020 ± 2.710 | 12.490 ± 2.687 |

| Senior and above | 104 (5.5) | 24.875 ± 4.828 | 12.320 ± 1.988 | 12.660 ± 2.028 |

| F | 0.971 | 0.988 | 0.764 | |

| p | 0.405 | 0.398 | 0.514 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Han | 1681 (89.3) | 24.870 ± 5.462 | 12.210 ± 2.883 | 12.660 ± 2.904 |

| Zhuang | 16 (0.9) | 25.687 ± 5.688 | 12.810 ± 3.016 | 12.880 ± 2.986 |

| Hui | 21 (1.1) | 26.568 ± 4.399 | 12.590 ± 2.526 | 13.330 ± 2.309 |

| Other ethnic groups | 164 (8.7) | 24.823 ± 5.180 | 12.140 ± 2.795 | 12.680 ± 2.708 |

| F | 0.081 | 1.152 | 0.412 | |

| p | 0.493 | 0.327 | 0.745 | |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight | 297 (15.8) | 24.336 ± 5.729 | 12.030 ± 3.054 | 12.300 ± 2.031 |

| Normal weight | 1243 (66.0) | 25.097 ± 5.279 | 12.340 ± 2.764 | 12.760 ± 2.809 |

| Overweight | 180 (9.6) | 24.601 ± 5.801 | 11.990 ± 3.066 | 12.610 ± 3.045 |

| Obese | 162 (8.6) | 24.740 ± 5.396 | 11.980 ± 3.025 | 12.760 ± 2.845 |

| F | 2.295 | 1.927 | 1.976 | |

| p | 0.076 | 0.122 | 0.116 | |

| Only child | ||||

| Yes | 760 (40.4) | 25.188 ± 5.590 | 12.450 ± 2.909 | 12.740 ± 2.987 |

| No | 1122 (59.6) | 24.692 ± 5.309 | 12.070 ± 2.834 | 12.620 ± 2.801 |

| t | 1.677 | 2.260 | 0.847 | |

| p | 0.094 | 0.024* | 0.397 | |

| Academic discipline | ||||

| Liberal arts | 555 (29.5) | 24.279 ± 5.330 | 12.040 ± 2.822 | 12.680 ± 2.905 |

| Science | 244 (13.0) | 25.184 ± 5.414 | 12.380 ± 2.977 | 12.800 ± 2.742 |

| Engineering | 970 (51.5) | 25.062 ± 5.528 | 12.380 ± 2.878 | 12.680 ± 2.917 |

| Medicine | 105 (5.6) | 23.810 ± 4.532 | 11.510 ± 2.497 | 12.300 ± 2.453 |

| Agriculture | 8 (0.4) | 21.375 ± 8.765 | 10.500 ± 4.243 | 10.880 ± 4.643 |

| F | 2.437 | 3.863 | 1.362 | |

| p | 0.045 * | 0.004 ** | 0.245 | |

| Mean monthly living cost (CNY) | ||||

| ≤1000 | 58 (3.1) | 25.086 ± 6.435 | 12.520 ± 3.414 | 12.570 ± 3.229 |

| 1001–1500 | 492 (26.1) | 24.607 ± 5.427 | 12.110 ± 2.860 | 12.490 ± 2.883 |

| 1501–2000 | 847 (45.0) | 25.098 ± 5.217 | 12.310 ± 2.752 | 12.790 ± 2.769 |

| >2000 | 485 (25.8) | 24.800 ± 5.659 | 12.150 ± 3.010 | 12.650 ± 2.966 |

| F | 0.927 | 0.806 | 1.117 | |

| p | 0.427 | 0.491 | 0.341 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ou, J.; Han, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhu, D.; Lin, Q. Validation of the Positive Eating Scale in Chinese University Students and Its Associations with Mental Health and Eating Behaviors. Youth 2025, 5, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040135

Chen J, Xu W, Liu Y, Liu W, Ou J, Han Y, Wang C, Zhu D, Lin Q. Validation of the Positive Eating Scale in Chinese University Students and Its Associations with Mental Health and Eating Behaviors. Youth. 2025; 5(4):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040135

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jie, Wenting Xu, Yangling Liu, Wenjun Liu, Jing Ou, Yuanli Han, Chuxin Wang, Di Zhu, and Qian Lin. 2025. "Validation of the Positive Eating Scale in Chinese University Students and Its Associations with Mental Health and Eating Behaviors" Youth 5, no. 4: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040135

APA StyleChen, J., Xu, W., Liu, Y., Liu, W., Ou, J., Han, Y., Wang, C., Zhu, D., & Lin, Q. (2025). Validation of the Positive Eating Scale in Chinese University Students and Its Associations with Mental Health and Eating Behaviors. Youth, 5(4), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040135