Abstract

Social acceptance among peers is an important predictor of adolescents’ academic and social outcomes. This study investigates how social acceptance depends on adolescents’ engagement in watching TV and gaming. Based on Contact Theory, we expected that TV watching and gaming are linked to digital contact with peers, which in turn predicts acceptance among classmates. Data were drawn from a longitudinal study with two measurement points among 826 7th graders (M = 13.32 years; 47.6% girls). Multilevel analyses revealed that more TV watching and gaming were related to higher social acceptance cross-sectionally. This effect was mediated by greater digital contact with peers. However, no associations were found between contact via media and changes in acceptance over time. These results suggest that media use and related peer contact may be more relevant in short-term interactions when explaining adolescents’ acceptance among classmates. Implications and directions for future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage marked by intense peer interactions and a heightened need for social acceptance among peers (Allen & Loeb, 2015). Social acceptance is defined as an individual’s general likeability among the individual’s peers (Cillessen & Bukowski, 2018). Previous research has supported that students with increased levels of social acceptance are more likely to have greater well-being, higher academic, and more positive social outcomes (Almquist & Brännström, 2014; Muñoz-Silva et al., 2020; Chávez et al., 2022; Wentzel et al., 2021). It is therefore important to identify predictors of adolescents’ acceptance.

Existing studies provide evidence that both individual and contextual factors influence social acceptance. At the individual level, for example, it is known that prosocial behavior predicts social acceptance in a positive way (Chávez et al., 2022) and that aggressive behavior is negatively correlated with social acceptance (Laurent et al., 2020; Leflot et al., 2011). However, factors at the class level also have an impact: for example, foreign students are less accepted in classes with few foreigners (Hjalmarsson et al., 2023). Furthermore, it is known that the effect of behavior on social acceptance depends on the group norms in the class. For example, aggressive students are more accepted in classes with a high level of aggressive behavior (Chang, 2004).

A factor less considered is students’ media use and its association with their social acceptance among peers. Media technologies have become pervasive in contemporary society, significantly influencing social interactions and relationships with potentially both positive (Costabile & Spears, 2013) and negative outcomes (Escortell et al., 2023). Specifically, the advent of television and gaming as well as novel forms of contact via technology (e.g., social media, phone apps) can be expected to significantly affect the way adolescents engage with their peers (Costabile & Spears, 2013). The current study sheds light on this issue by investigating effects of TV watching and gaming on adolescents’ social acceptance among their classmates and the role that contact with peers via media plays in this context. Exploring these dynamics is crucial for an adequate understanding of youth development, promoting positive social outcomes, and creating inclusive environments for adolescents (Kowert & Kaye, 2018).

1.1. Contact Theory as a Theoretical Framework

Contact Theory, initially proposed by Allport (1954), posits that positive intergroup interactions can lead to more positive attitudes and reduced prejudice between individuals from different social, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds. It is proposed that positive effects of contact are promoted when, for instance, intergroup interactions are characterized by equal status, cooperation towards common goals, and support from authorities or influential figures within the social group (Allport, 1954). Additionally, the quality of interactions and the presence of positive emotions during contact play a crucial role in determining its impact on individuals (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

While Contact Theory has primarily been studied in the context of reducing intergroup bias, its principles also hold relevance in understanding peer social acceptance within social groups, suggesting that increased exposure and positive interactions between peers can contribute to greater acceptance (Allport, 1954; Kowert & Kaye, 2018). Binder et al. (2009) explored how cross-group friendships and interactions influenced social acceptance among adolescents from diverse backgrounds. Their findings indicated that increased contact between individuals of different ethnic groups led to enhanced social acceptance and reduced feelings of isolation among marginalized individuals (Binder et al., 2009). Additional research on Contact Theory across peer networks’ sports, schools, leisure, and social media explored how social relationships were formed among social groups, specifically adolescent athletes (Dalen & Seippel, 2021). While this is a specialized group, the findings could potentially be generalized to other social groups. The results indicated that the adolescents’ relationships were formed through a combination of different types of contact including social media use, cooperative gaming, media consumption, and existing school networks (Dalen & Seippel, 2021). These findings support the importance of encouraging and facilitating students’ contacts with each other across a wide variety of situations and methods (Dalen & Seippel, 2021).

In terms of theorizing on the association between TV watching and gaming with peer acceptance, it can be expected that engagement in these activities affects the frequency and quality of social contact among peers. Importantly, such social contact may not necessarily occur via direct interaction with peers being present (e.g., being in the same room), but in today’s media environment may often occur via technology (e.g., texting or messaging via smartphones). Different amounts of such social contact in turn may be associated with differential acceptance among peers, which will be pointed out in more detail in the following.

1.2. Watching TV and Gaming and Their Relation to Contact and Acceptance

Watching television has been a long-standing form of entertainment. Generally, TV content can form a common ground for discussion and sharing norms among peers (Cheong et al., 2023). For example, shared interests in specific television shows can contribute to bonding and acceptance among peers (Plaisier & Konijn, 2013). Also, research suggests that media content, including TV shows, can shape adolescents’ social norms and behaviors which may impact their social competence and therefore acceptance within peer groups (Arias, 2019). In recent years, many people’s TV consumption has shifted to an on-demand model of TV watching where they will watch shows via a streaming service such as Netflix or YouTube when they have time (Tefertiller, 2018). In terms of watching TV and its relation to social contact and acceptance among adolescents, many different types of consequences may occur. On the one hand, watching TV or streaming videos can be viewed as a primarily passive, non-social activity during which adolescents often are not among their peers and have less direct interaction among each other (Hipson et al., 2021). Therefore, adolescents may miss opportunities of positive contact that could lead to more social acceptance. On the other hand, new forms of social contact among peers via media, such as smartphones or other devices, may very well allow social interaction before watching TV (e.g., arrange to commonly watch a TV show at each person’s home), during (e.g., exchange on what is happening in a show) or after (e.g., exchange on how the show was liked). Hence, in today’s media landscape, TV is often considered a non-social activity; however, it could be associated with co-occurring contact with peers via media which in turn may be associated with social acceptance among peers. The latter is consistent with the findings of Flayelle et al. (2019), who found a “social factor” of television consumption as part of a validation of a questionnaire on television consumption and binge watching. The respective factor includes aspects of belonging and being able to have a say as well as peer pressure to watch certain series. Research in fact indicates that contact via media is an important aspect of how adolescents communicate with each other and how they experience social belonging among peers with over 90% of adolescents in developed countries using some type of social media (Smith et al., 2021). Yet, we found that empirical evidence on the association of the duration of TV watching, frequency of contact via media and peer acceptance is lacking (Dredge & Schreurs, 2020).

Another frequent form of media use is video gaming. This activity can include both gaming alone and using multiplayer (online) games. Gaming has become a popular leisure activity among adolescents, and it has the potential to influence their social interactions and peer acceptance (Hanghøj et al., 2018; Kowert, 2020; Kowert & Kaye, 2018). Underlying mechanisms with regard to social contact and acceptance may be similar as for TV watching (Elareshi et al., 2022). Solitary, excessive gaming or involvement in certain gaming subcultures may lead to less real-life peer interaction and subsequent challenges in establishing peer acceptance (Williams, 2018). One study by Shawcroft et al. (2022) found that when adolescents allocate excessive time to gaming, this can reduce opportunities for face-to-face interactions and engagement in real-world social activities. In contrast, another study found that gaming can also allow positive exchange via media between adolescents before, during, or after this activity and may provide opportunities for adolescents to engage in cooperative or competitive activities with peers that can foster a sense of belonging and social acceptance (Hanghøj et al., 2018). Importantly, having these new possibilities, gaming may not always be a purely non-social activity but could go hand in hand with social contact via media among peers. In conclusion, the aforementioned studies indicate that knowledge on the specific associations of engagement in gaming, frequencies of contact via media with peers, and acceptance has tangentially been explored but that the results are mixed and depend on the study context. The present study shall offer novel insights into the relationship between media consumption and social acceptance.

1.3. The Current Study

In light of existing research, the present study aimed to explore how the daily duration of TV watching and gaming among adolescent students is related to their social acceptance among their classmates and whether this is mediated by the frequency of contact with classmates via media. We were specifically interested in the aspect of contact via media given that in recent years technological progress has added various new options for adolescents to interact with their peers without meeting them in person. Focusing on the classroom peer context, we expected that both more TV watching and gaming would predict more contact via media with classmates, which in turn predicts higher social acceptance for adolescents in their classroom. Contact via media was therefore expected to mediate the relation between TV watching and gaming and adolescents’ social acceptance.

We used data collected among early adolescents in Switzerland between 2011 and 2012, a period that marked an important shift in adolescents’ media habits. At that time, digital technologies such as social media, mobile phones, and online gaming were rapidly becoming embedded in everyday life (Willemse et al., 2012). While the platforms and tools available have evolved since then, the fundamental behaviors and social dynamics initiated during this era laid the foundation for many of the interactions that remain central to adolescent experiences today. By focusing on this transitional phase, the study captures patterns that are still relevant, as the underlying mechanisms of peer interaction via media—such as using technology to connect and maintain relationships—are not tied to a specific technological moment. The study’s findings on media use as a predictor of social acceptance and communication via media as a mediator also provide valuable context for interpreting how contemporary platforms like TikTok or online multiplayer games might influence peer dynamics (Costabile & Spears, 2013; Kowert & Kaye, 2018). These processes remain central to understanding adolescent development and peer dynamics in any media landscape.

We used a combination of cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal analyses, which allowed different insights into mechanisms of media use, social contact, and social acceptance immediately and over time: while cross-sectional data captures a snapshot of relations between different factors at a specific point in time longitudinal data provides information on change and dynamic processes over certain time period. Hence, by integrating both types of data, we aimed to gain a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon, capturing the intricate interplay between time and context which is essential for addressing contemporary challenges in adolescent peer interactions (Smith et al., 2021).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The entire cohort of a rural, German-speaking region of Switzerland that entered secondary school in the fall of 2011 was included in the current study. Secondary school in this region starts with Grade 7 and classrooms are newly composed at that time (August). In this school system students remain in their self-contained classrooms for nearly all their courses (religion lessons being one exception). This means that student composition in classrooms does not change across the entire school day. Measurements were conducted when students were in 7th grade with T1 in November or December of 2011 (depending on the classroom) and T2 in February or March of 2012. The sample at these measurement points comprised 826 students, distributed among 56 classrooms spanning eight different schools. Because the research was part of a collaborative evaluation study by the local School Administration and University (see Section 2.3), participation was high among students (T1: 97.6% of the whole student population of n = 826; T2: 94.9%). At the initial measurement (T1), the average age of participants stood at 13.32 years (SD = 0.48; range = 11.67–15.08 years). In the sample, 47.6% of the participants were female based on self-report.

2.2. Measures

Table 1 provides an overview of the measurement instruments used in the current study.

Table 1.

Summary of measures and their operationalization.

TV watching. At T1, students self-reported on the duration (in hours and minutes) of their TV watching per day. For our analyses, students’ reports were calculated in hours.

Gaming. Participants at T1 reported on how much time per day they spent gaming (explained as electronic games played on a computer, PlayStation, Wii, cell phone/telephone, etc.) per day. Again, the total number of hours was used for our analyses.

Contact via media. At T1, students were asked on how many of the last 14 days they exchanged with each of their classmates using a cell phone/telephone or via internet (e.g., calls, SMS, E-mails, chats, messaging, Facebook, etc.). Participants saw a list of all their classmates and for each reported a number between 0 and 14 days. For our analyses, a mean of these self-reported numbers was calculated for each reporting student. An example would be that Thomas reported having had contact with Kevin on 2 days, with Maria on 4 days, and with John on 0 days, resulting in a mean for Thomas of 2 days (2 + 4 + 0/3).

Social acceptance. Acceptance among classmates at T1 and T2 was measured using peer nominations when asked the question with whom individual students spend most of their time when being at school. This interaction frequency-oriented operationalization is grounded in findings by Newcomb and Bagwell (1995), who showed that frequent social contact is associated with friendship, willingness to share, and willingness to cooperate. For our analyses we used the percentage of possible nominations individually received from the classmates (e.g., Thomas received 5 out of 20 possible nominations so he had a score of 25%; Bukowski et al., 2000).

2.3. Procedure

This research was part of the collaborative evaluation project “Fribourg Study on Peer Influence in Schools”. The overall goal was to better understand students’ social development and challenges after transitioning from primary to lower secondary school in the local school system. As such, School Administration decided that all classrooms and students in the canton from this cohort would be asked to participate in the study, provided that there is absolute anonymity of the participants’ reports. Based on this decision, an informational letter by School Administration and University was sent to parents including the information that students would never provide their names and that no individual data from students’ reports would be given to others. Both parents and students always had the opportunity to decline participation. The project underwent a peer review process by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

For data collection, trained research assistants followed a detailed manual to collect the data. The questionnaires were completed by paper and pencil inside the classroom, and students had to place mobile screens on their desk to assure the independence of their answers. Participants never gave their names and were assigned a numeric code so that complete anonymity was assured. Data were combined across waves using these numeric codes.

2.4. Data Analysis

In the current analysis we included both cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal data using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM). HLM is an approach that allows researchers to control for the clustering of individuals within higher-level units (e.g., classrooms) and therefore to avoid biased estimates of standard errors. It further allows to examine the effects of variables at different levels of analysis (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In the present study, there were variables exclusively at Level 1 (individual) and not at Level 2 (classroom), but we considered the hierarchical data structure by estimating the variance between classrooms. We conducted the analyses with the software Mplus Version 8.0, which uses maximum likelihood parameter estimates with robust standard errors (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

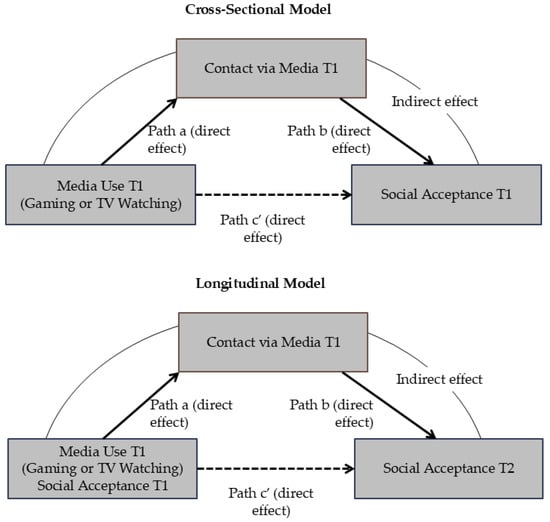

We conducted cross-sectional and longitudinal mediator analyses (Kenny & Judd, 2014; Rose et al., 2004). Significance of indirect effects was tested using the delta method (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The z-test used by Mplus in the delta method is based on a similar approach to the Sobel test (Sobel, 1987) but is implemented in a more general and precise way. The analyses were conducted separately for the two types of media use (i.e., gaming and TV consumption). In the cross-sectional model, we predicted social acceptance at T1 by media use at T1 (gaming and TV consumption) via the mediator social media contact with peers from class at T1. In the longitudinal model, social acceptance at T2 was predicted by media use at T1 via the mediator at T1, controlling for social acceptance at T1. By controlling the baseline score, change (increase or decrease) in social acceptance depending on the predictor/mediator variables was assessed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal mediator analyses.

In our analyses, we controlled for students’ gender as some research suggests that boys and girls differ in their consumption of media with girls spending more time on their cell phones, social media, and texting; while boys spend more time video gaming (Twenge & Martin, 2020).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

Descriptive statistics depicted in Table 2 show that students had an average acceptance rate of nearly 20% (range: 0–61.11 at T1; 0–61.54 at T2), indicating that they were on average nominated by 20% of their classmates as persons with whom they often spend time with at school. The descriptively seen small increase in acceptance from T1 to T2 was not significant (p = 0.548). The high correlation between T1 and T2 acceptance (r = 0.63; p < 0.01) indicates that those with a high acceptance rate at T1 also scored higher at T2. Social acceptance at T1 and T2 correlated low but significantly (p < 0.001) with the daily time spent on contact with peers from class via social media. However, there were no bivariate correlations of acceptance with the amount of time students spend per day with gaming and watching TV. In addition, male gender was related to higher levels of time spent gaming (r = 0.29, p < 0.01) and TV consumption (r = 0.07, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables.

3.2. Cross-Sectional Results

Results of cross-sectional HLM models are presented in Table 3 and Table 4, where each table includes a different form of media use (either gaming or TV consumption). The first column shows the effects of the independent variables on the mediator (contact with peers from the class via social media), while the second column shows the effects on social acceptance (at the same measurement point). According to the criteria for mediator analyses, an indirect effect can only be tested if both the independent variable (i.e., the two variables of media use) exerts a significant effect on the mediator (i.e., contact with peers from class via social media) and the mediator exerts an effect on the dependent variable (i.e., social acceptance).

Table 3.

Direct and indirect effects of the cross-sectional mediation model predicting social acceptance by gaming.

Table 4.

Direct and Indirect effects of the cross-sectional mediation model predicting social acceptance by TV consumption.

For each form of media use, gaming and TV consumption, a significant direct effect was found on the mediator (from p = 0.001 to p = 0.009), indicating that the more time was spent using media, the more contact students had with the peers from class via social media. In addition, the mediator contact via social media was significantly related to social acceptance in each model (p < 0.001), indicating that more social media contact with peers from class is associated with higher social acceptance in class. All indirect effects were also significant (from p = 0.008 to p = 0.026), which means that both forms of media use (i.e., gaming and TV) were related to higher social acceptance in class via increased social media contact with peers from class.

3.3. Longitudinal Results

In the longitudinal mediator models, we predicted a change in social acceptance from T1 to T2 by controlling for T1 social acceptance (see Table 5 and Table 6). In these models, the direct effects of T1 media use (i.e., gaming and TV consumption) on the mediator contact with peers from class via social media at T1 remained all significant (from p = 0.001 to p = 0.006). However, the mediator contact via social media did not predict a change in social acceptance in any of the two models. Hence, since the assumptions were not met, we did not calculate the indirect effects of media use on social acceptance. In addition, no direct effects on social acceptance were found for gaming and TV consumption.

Table 5.

Direct effects predicting change in social acceptance by gaming at T1.

Table 6.

Direct Effects Predicting Change in Social Acceptance by TV Consumption at T1.

3.4. Further Analyses

For our measurement of contact with peers via media, we used an instrument that related to contact with the specific peer group of classmates. In the present study, this approach has the advantage that both the measurement of contact and acceptance relate to the classroom peer context. To test the reliability of these findings, we conducted further analyses on when contact via media is operationalized as being non-specific to the classmates (e.g., when contact partners can also include other peers from school or even persons only met via the internet). To explore this, participants at T1 were asked how much time per day (measured in hours) they spend with others exchanging via cell phone/telephone or internet (e.g., calls, text messages, e-mails, chat, MSN, Facebook, etc.). Using this alternate measure, where contact partners were not defined (i.e., “others”) as a mediator, results show a similar pattern regarding cross-sectional results. There was a significant indirect effect of gaming, which is associated with greater acceptance through a higher level of contact (B = 0.598, SE = 0.133, B/SE = 4.493, p < 0.001). The same was found when using TV consumption as predictor (B = 0.530, SE = 0.126, B/SE = 4.196, p < 0.001). The longitudinal results still revealed no significant indirect effects regarding both gaming (B = 0.147, SE = 0.102, B/SE = 41.450, p = 0.147) and TV consumption (B = 0.142, SE = 0.092, B/SE = 1.539, p = 0.124). Hence, results from our main analyses can be considered to be reliable, even when changing operationalizations slightly.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the associations between adolescents’ media utilization, with a specific focus on gaming and television viewing, and their social acceptance amongst peers. We analyzed both cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal data to discern the nuanced role that media engagement plays in the social milieu of adolescents.

Overall, adolescents reported using between one and two hours a day for gaming and watching TV each on average; however, there was large variation between subjects and boys showed more use. In terms of our main question, cross-sectional analyses revealed a noteworthy relation: more media consumption was directly linked to enhanced peer contact through social media, corroborating postulations based on Contact Theory that media serves as a facilitator for social exchanges (Bond et al., 2023). This observation is consistent with Dalen and Seippel’s (2021) findings, which underscore the significance of various modalities of contact, media included, in shaping adolescents’ social networks. In turn, more peer contact via social media was associated with greater social acceptance. This is in line with other findings that have shown that more social contact (non-specific to media use) is linked to more social closeness among peers (e.g., Altman et al., 2020; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). The fact that media use was mediated by contact supports our initial expectation for the cross-sectional part of our analyses.

The short-term longitudinal analyses added complexity to the narrative because peer contact failed to translate into enhanced social acceptance in the near future and was therefore not in support of our expectation. Hanghøj et al. (2018) reported similar findings, acknowledging cooperative gaming’s potential to promote social engagement and participation while also recognizing its constraints in sustaining these connections. In a straight-forward interpretation, our results from the short-term longitudinal analyses would therefore suggest a disjunction between the initiation of interaction and the cultivation of enduring peer relationships, thereby challenging the applicability of Contact Theory to digital interactions over time. However, an important reason for the lack of an effect for contact via media on acceptance could also be the relatively stable nature of social acceptance (Ilmarinen et al., 2019) that can be rooted in longer-term relationships and established social structures within peer groups. Whether this aspect explains the present results must remain open, because classrooms in this sample were newly composed three or four months before T1 so that peer relation structures may nevertheless be expected to develop across the next few months. In line with this, constantly changing media offers (e.g., new TV shows, games, youtube personalities, etc.) and related opportunities for peer interaction can be expected to support new peer relations also in rather short periods of time (even if the amount of media consumption remains the same). Overall, since there is little evidence of how media consumption and social acceptance change in rather short time intervals, the results of our longitudinal analyses should be regarded as exploratory and clearly need replication and extension in terms of analyzing longer term relations.

4.1. Implications

Theoretical implications of this study relate to the importance of differentiating between immediate and over time processes when aiming to understand the relations between media use, contact, and social acceptance among peers. Our cross-sectional analyses and measures related either to what adolescents did (media use, contact in recent time) or experienced (social acceptance) recently and for these factors we found the expected relations. In contrast, these measures did not predict changes in acceptance in the near future. One may therefore conclude that media-related contact is mainly of importance for explaining current social situations among peers but has less impact over time. At this point, it would be interesting to consider in more detail how contact via media is related to interactions among peers. One hypothesis could be that only when contact via media impacts on specific real-life interactions among classmates, effects on the development of acceptance in the classroom can be expected. In this regard, the salience of interactions in terms of eliciting relevant cognitive and emotional processes among adolescents may be required to provoke behavioral changes. For example, based on Contact Theory students may only experience social interactions as rewarding and changing their view on others when they are characterized by equal status and cooperation towards common goals (Allport, 1954). More research is needed to shed light on these questions.

From a practical standpoint, our findings imply that digital media may act as a catalyst for social interactions, but these may require reinforcement through substantive engagement to mature into meaningful relationships. In line with Dredge and Schreurs (2020), our results may therefore encourage educators to use media for collaborative learning and positive social interactions among peers that translate into real-life interactions, fostering social competence and positive social status among students.

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study enriches our knowledge on how media use is related to adolescents’ situation among their peers. By testing the expectation that today’s media use is often not primarily a non-social activity but allows for alternative forms of contact with peers that impact on their social status, we could shed more light on the mechanisms why media use may be related to social acceptance. Using state of the art methods of cross-sectional and short-term longitudinal data analyses, and conducting sensitivity analyses with alternative forms of operationalization, our results provide reliable insights into the questions at hand.

In terms of limitations it is of note that the dataset analyzed stems from 2011/2012, a time marked by the widespread integration of social media, mobile phones, and online gaming into the daily lives of adolescents (Willemse et al., 2012). Since this period, the proliferation of smartphones has further increased (Statista, 2024), new platforms such as TikTok and Snapchat have spread widely and even more media multitasking may be required among adolescents (e.g., Cain et al., 2016). Hence, our interpretations may be on the more conservative side because today’s media provides even more opportunities for contact and common media consumption among peers. In our view, future research may expect that the relations between media use, contact, and acceptance are even higher compared to the present results. On the other hand, it needs to be kept in mind that media consumption (especially excessive consumption) can also have negative consequences for social relationships (see e.g., Sussman & Moran, 2013). This is the case when consumption becomes similar to an addiction and social life is being neglected. Against this background of potential differences in the effects of media consumption, it is particularly important to replicate the findings of the current study, taking into account the increasing digitization and related changes in adolescents’ daily social interactions.

Another issue is that our contact measure only related to contact via media, and we did not have more information on the contents of media consumed and of the exchanges among peers. Future research may benefit from adding measures that also assess real-life contact between peers, providing additional information on how media use translates to contact via media, direct social interaction and social acceptance. Similarly, the specific media behavior engaged in were not measured, only the time spent on media. Future research could explore how different types of media behaviors such as sharing content on social media or gaming together impact peer acceptance differently.

With regard to our analyses over time, it should be noted that only social acceptance was measured at both measurement points, but not media consumption and contact via media. It was therefore not possible to additionally take into account changes in media use over time. Furthermore, and as mentioned above, the relatively short time interval between T1 and T2 could also have contributed to an underestimation of change processes in social acceptance, clearly pointing to the need for future studies investigating longer-term relations.

Finally, it should be kept in mind that studies asking students to report on their media use and social lives are always conducted in specific cultural and socio-economic contexts. This study has been conducted in Switzerland which is a Western country where most adolescents have simple access to various types of media. Given that the media and technological industry is internationally influential, a great amount of media formats and content (e.g., movies, TV shows, video games, etc.) is similar in the Western world. In this regard, our results on the mechanisms investigated can be expected to be mostly applicable to other Western countries. For other regions, where access to media may be more restricted and contents may differ, it is less clear in how far our results apply. In the light of the general human desire for acceptance by others (DeWall & Bushman, 2011) and increasing access to media worldwide (ITU, 2024), it would be interesting to further examine the topic at hand on a global level.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the present results point to the importance of explicitly integrating media use in peer relations research. More classic views of media use as being primarily non-social may miss the opportunities and therefore the impact that media use has on how today’s adolescents interact with each other, shaping their relationships. At the same time, the results of this study point to the need to further assess long-term relations between media use and peer relationships. In this regard, it will also be of great interest to better understand the relations between contact via media and real-life classroom interactions in the future, aiming to better understand and support adolescents’ social welfare in their peer context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.O.K., C.M.M., D.L. and V.H.; Methodology, V.H.; Formal analysis, V.H.; Investigation, V.H. and C.M.M.; Writing—original draft, V.H., R.O.K., C.M.M. and D.L.; Writing—review & editing, R.O.K. and C.M.M.; Project administration, C.M.M.; Funding acquisition, C.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation, grant numbers 132210 and 143459.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since the data used in the present paper stem from an educational research project. As in Switzerland educational research projects are not treated by the official Swiss ethics commissions and in 2010 it did not yet exist an institutional ethics commission at the Department of Special Education of the University of Fribourg (which is now in place), there is no statement of an ethics commission on this project. However, the project underwent anonymous peer review in the application process by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF-132210, 2010).

Informed Consent Statement

Data collection was completely anonymous and did not involve assessment of any information that would allow identification of individual participants (i.e., names or other student identifiers). Hence, participants’ passive consent was assessed. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and withdrawal was possible at any time without consequences.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, J. P., & Loeb, E. L. (2015). The autonomy-connection challenge in adolescent-peer relationships. Child Development Perspectives, 9(2), 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Almquist, Y. B., & Brännström, L. (2014). Childhood peer status and the clustering of social, economic, and health-related circumstances in adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 105, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, R. L., Laursen, B., Messinger, D. S., & Perry, L. K. (2020). Validation of continuous measures of peer social interaction with self- and teacher-reports of friendship and social engagement. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E. (2019). How does media influence social norms? Experimental evidence on the role of common knowledge. Political Science Research and Methods, 7(3), 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J., Zagefka, H., Brown, R., Funke, F., Kessler, T., Mummendey, A., Maquil, A., Demoulin, S., & Leyens, J. P. (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J., Dixon, J., Tredoux, C., & Andreouli, E. (2023). The contact hypothesis and the virtual revolution: Does face-to-face interaction remain central to improving intergroup relations? PLoS ONE, 18(12), e0292831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W. M., Sippola, L. K., Hoza, B., & Newcomb, A. F. (2000). Pages from a sociometric notebook: An analysis of nomination and rating scale measures of acceptance, rejection, and social preference. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2000(88), 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, M. S., Leonard, J. A., Gabrieli, J. D., & Finn, A. S. (2016). Media multitasking in adolescence. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. (2004). The Role of classroom norms in contextualizing the relations of children’s social behaviors to peer acceptance. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, D. V., Salmivalli, C., Garandeau, C. F., Berger, C., & Kanacri, B. P. L. (2022). Bidirectional associations of prosocial behavior with peer acceptance and rejection in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(12), 2355–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, J. H., Molani, Z., Sadhukha, S., & Chang, L. J. (2023). Synchronized affect in shared experiences strengthens social connection. Communications Biology, 6(1), 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cillessen, A. H. N., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Sociometric perspectives. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 64–83). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costabile, A., & Spears, B. A. (2013). The impact of technology on relationships in educational settings (illustrated ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalen, H. B., & Seippel, Ø. (2021). Friends in sports: Social networks in leisure, school and social media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, C. N., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). Social acceptance and rejection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, R., & Schreurs, L. (2020). Social media use and offline interpersonal outcomes during youth: A systematic literature review. Mass Communication & Society, 23(6), 885–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elareshi, M., Habes, M., Al-Tahat, K., Ziani, A., & Salloum, S. A. (2022). Factors affecting social TV acceptance among generation Z in Jordan. Acta Psychologica, 230, 103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escortell, R., Delgado, B., Baquero, A., & Martínez, M. M. C. (2023). Special issue: Child protection in the digital age Latent profiles in cyberbullying and the relationship with self-concept and achievement goals in preadolescence. Child & Family Social Work, 28(4), 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayelle, M., Canale, N., Vögele, C., Karila, L., Maurage, P., & Billieux, J. (2019). Assessing binge-watching behaviors: Development and validation of the “Watching TV Series Motives” and “Binge-watching Engagement and Symptoms” questionnaires. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanghøj, T., Lieberoth, A., & Misfeldt, M. (2018). Can cooperative video games encourage social and motivational inclusion of at-risk students? British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(4), 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipson, W. E., Coplan, R. J., Dufour, M., Wood, K. R., & Bowker, J. C. (2021). Time alone well spent? A person-centered analysis of adolescents’ solitary activities. Social Development, 30(4), 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalmarsson, S., Fallesen, P., & Plenty, S. (2023). Not next to you: Peer rejection, sociodemographic characteristics and the moderating effects of classroom composition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(6), 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, V., Vainikainen, M., Verkasalo, M., Lönnqvist, J., & Back, M. (2019). Peer sociometric status and personality development from middle childhood to preadolescence. European Journal of Personality, 33(5), 606–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2024). Facts and figures 2024. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/facts-figures-2024/index/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Kenny, D. A., & Judd, C. M. (2014). Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychological Science, 25(2), 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowert, R. (2020). Dark participation in games. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 598947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowert, R., & Kaye, L. K. (2018). Video games are not socially isolating. In C. J. Ferguson (Ed.), Video game influences on aggression, cognition, and attention (pp. 185–195). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, G., Hecht, H. K., Ensink, K., & Borelli, J. L. (2020). Emotional understanding, aggression, and social functioning among preschoolers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(1), 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leflot, G., Van Lier, P., Verschueren, K., Onghena, P., & Colpin, H. (2011). Transactional associations among teacher support, peer social preference, and child externalizing behavior: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Silva, A., De la Corte de la Corte, C., Lorence-Lara, B., & Sanchez-Garcia, M. (2020). Psychosocial adjustment and sociometric status in primary education: Gender differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 607274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Newcomb, A. F., & Bagwell, C. L. (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 306–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisier, X. S., & Konijn, E. A. (2013). Rejected by peers—Attracted to antisocial media content: Rejection-based anger impairs moral judgment among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 49(6), 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). SAGE Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, B. M., Holmbeck, G. N., Coakley, R. M., & Franks, E. A. (2004). Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(1), 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawcroft, J., Coyne, S. M., & Bradshaw, B. (2022). An analysis of the social context of video games, pathological gaming, and depressive symptoms. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(12), 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D., Leonis, T., & Anandavalli, S. (2021). Belonging and loneliness in cyberspace: Impacts of social media on adolescents’ well-being. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M. E. (1987). Direct and indirect effects in linear structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2024, December 12). Number of smartphone users worldwide 2014–2029. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1143723/smartphone-users-in-the-world (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Sussman, S., & Moran, M. B. (2013). Hidden addiction: Television. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefertiller, A. (2018). Media substitution in cable cord-cutting: The adoption of web-streaming television. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 62(3), 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., & Martin, G. N. (2020). Gender differences in associations between digital media use and psychological well-being: Evidence from three large datasets. Journal of Adolescence, 79(1), 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., Jablansky, S., & Scalise, N. R. (2021). Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, I., Waller, G., Süss, D., Genner, S., & Huber, A.-L. (2012). JAMES—Jugend, aktivitäten, medien—Erhebung schweiz [JAMES—Youth, activities, media—Survey Switzerland]. Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. (2018). For better or worse: Game structure and mechanics driving social interactions and isolation. In C. J. Ferguson (Ed.), Video game influences on aggression, cognition, and attention (pp. 173–183). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).