Abstract

This paper investigates the flow of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid through a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium under Cattaneo–Christov heat and mass flux models. The hybrid nanofluid, composed of alumina and copper nanoparticles in water, enhances thermal and mass transport, while the second-grade model captures viscoelastic effects, and the Darcy–Forchheimer medium accounts for both linear and nonlinear drag. Using similarity transformations and the spectral quasilinearisation method, the nonlinear governing equations are solved numerically and validated against benchmark results. The results show that hybrid nanoparticles significantly boost heat and mass transfer, while Cattaneo–Christov fluxes delay thermal and concentration responses, reducing the near-wall temperature and concentration. The distributions of velocity, temperature, concentration, and microorganism density are markedly affected by porosity, the Forchheimer number, the bio-convection Peclet number, and relaxation times. The results illustrate that hybrid nanoparticles significantly increase heat and mass transfer, whereas thermal and concentration relaxation factors delay energy and species diffusion, thickening the associated boundary layers. Viscoelasticity, porous medium resistance, Forchheimer drag, and bio-convection all have an influence on flow velocity and transfer rates, highlighting the subtle link between these mechanisms. These breakthroughs may be beneficial in establishing and enhancing bioreactors, microbial fuel cells, geothermal systems, and other applications that need hybrid nanofluids and non-Fourier/non-Fickian transport.

1. Introduction

Second-grade (Rivlin–Ericksen) fluids represent a class of non-Newtonian media whose stress depends on both the instantaneous and first Rivlin–Ericksen tensors, thereby exhibiting combined viscous–elastic behaviour [1]. In contrast to Newtonian fluids, the stress in second-grade fluids is influenced not only by the current strain rate but also by the fluid’s distortion history. The unique feature makes them ideal for modelling complex flow behaviours in examples like polymeric substances, biological materials, and certain oil-based lubricants. These properties are key to understanding intricate engineering problems. Rivlin and Ericksen [2] established and developed the notion of second-grade fluids. Nanofluids, fluids infused with nanoscale particles, have attracted widespread interest for their enhanced thermal and rheological properties. They are very effective in heat transfer applications because of these characteristics. Engineering applications for nanofluids include microfluidics, heat dissipation systems and green energy systems. They are crucial to modern fluid mechanics because of their ability to enhance heat transport while consuming less energy. Choi [3] first proposed the idea of a “nanofluid” in his groundbreaking research. Nisar et al. [4] undertook a theoretical analysis of nanofluid movement. Nisar and Berrouk [5] conducted a study evaluating computational models of nanofluids containing nanofluids incorporating carbon nanotubes and magnetite in an enclosed domain.

A hybrid nanofluid incorporates two or more distinct nanoparticle species (e.g., metal oxides and metals) into a single carrier fluid, thereby synergistically boosting effective heat conductivity and specific heat capacity. The combination improves thermal transfer efficiency, viscosity, and thermal conductivity, providing better performance than conventional single-particle nanofluids [6]. The combination of metal oxides (for example, Al2O3 and TiO2) with metallic nanoparticles (for example, Cu and Ag) increases thermophysical characteristics, making hybrid nanofluids particularly efficient in energy-intensive applications [7]. Due to their outstanding heat dissipation properties, they are widely used for nuclear reactor coolant systems, solar energy harvesting, biomedical applications, electronic device cooling, and industrial cooling systems, as well as automobile heat exchangers [8]. Nadeem et al. [9] assessed the significance pertaining to thermal transfer within the circulation of second-grade nanofluid hybrid fluids along a stretching/shrinking Riga wedge, and according to their analysis, hybrid nanofluids provide a higher heat transfer rate than nanofluids. Arif et al. [10] explored the significance of stretching and activation energy on the flow of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid along a flat plate. It has been proven that the performance of hybrid nanofluid is efficient in several conditions when compared to nanofluid and conventional fluid. Concurrently, Nadeem et al. [11] numerically assessed the flow and thermal response of the same fluid flowing over a permeable interface surface subjected to stretching or shrinking, and also the hybrid nanofluid outperformed the nanofluid. Mohamed et al. [12] investigated the use of a hybrid nanofluid containing nanoparticles to study the unstable boundary layer stagnation-point flow, with simultaneous mass and heat transfer over a stretching sheet. Khan et al. [13] studied nonlinear mixed convective hybrid nanofluid flow over a porous, inclined stretching surface, emphasising its role in heat transfer applications and accounting for plate porosity and microorganisms.

During bioconvection, a natural process, microorganisms move randomly in colonies or single-cell configurations. The bio-convection systems work by directing the mobility of various microbes. The suspension thickens towards the top of the still water because gyrotactic microorganisms tend to swim upward against gravity. Among the many applications of bioconvection in biology and industry are biological fuels, organic microtechnologies, ethanol, and plant fertilisers. Bio-convection is increasingly important in oil refinery processes and is employed as a technique in enzyme biosensor applications. As a result of these unique characteristics, a variety of applications have been examined by researchers. Wang et al. [14] investigated the computational analysis for bio-convection of microorganisms in Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Prandtl nanofluids in porous media along an angled surface. Waqas et al. [15] explored the flow dynamics of a modified second-grade nanofluid embedded with gyro-tactic microorganisms and nanoparticles under bio-convection conditions, and they discovered that the buoyancy ratio parameter and the bioconvection Rayleigh number both significantly reduced the velocity profile. Alshormani et al. [16] numerically examined the bio-convection of a viscoelastic nanofluid. In another study, Chu et al. [17] explored MHD bio-convection with thermal transfer in a non-Newtonian fluid flowing past a stretching surface employing Buongiorno’s model. Their results showed that the velocity field decreases as the magnetic parameter increases. Dey et al. [18] studied the flow of a dusty nanofluid along a vertically expanding surface. In the area of MHD bio-convection, Ferdows et al. [19] worked on enhancing heat transfer by using a highly flexible sheet to improve the flow of nanofluids, and in their study they found that the density of motile microorganisms decreases with the bioconvection Lewis number, Prandtl number, Lewis number, and Peclet number. Irfan et al. [20] took a closer look at the unsteady MHD flow of a bio-nanofluid moving through a porous medium, paying special attention to how thermal radiation affects the fluid near a shrinking sheet. At the same time, Khan et al. [21] focused on understanding entropy generation in bio-convective nanofluid flow between two stretching and rotating discs. Ahmedet al. [22] investigated the flow of an electrically guided Fe3O4-Cu/water hybrid nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms near a flat stagnation point over a horizontal, permeable, stretching sheet, considering the effects of an external attractive field. Tanveer et al. [23] also conducted an entropy analysis, which showed that hybrid nanofluids generate less entropy compared to conventional nanofluids.

The movement of homogeneous fluids through a porous medium was studied by Henry Darcy [24]. The research was conducted for low-permeability media and tiny velocities. Later, Forchheimer [25] overcame the drawbacks of Darcy’s work by including the square of the flow factor in the flow equation. Muskat [26] first identified the additional phrase as ’Forchheimer’. Following that, other people did a lot of investigations employing different geometries for fluid flow and heat transmission through permeable media. Enamul et al. [27] explored the MHD flow and entropy generation of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid confined between rotating discs within a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium, considering changes in thermal conductivity. When the Reynolds number and titanium dioxide nanoparticle concentration are increased, the heat transfer rate at both discs improves. Ali et al. [28] focused on bio-convection in a Jeffery fluid under similar porous conditions. Further extending this research, Sohail et al. [29] looked into the bio-convective flow of a Maxwell nanofluid over a stretching surface, considering thermal radiation and Darcy–Forchheimer effects, and used homotopy analysis to solve the problem. They found that the Deborah number, which was calculated from the Maxwell model’s relaxation time, slowed the fluid and increased the temperature and concentration profile. Complementing these works, Algehyne et al. [30] executed a computational investigation on bio-convection and heat transfer within the nanofluid flowing across a permeable vertical plate under Darcy–Forchheimer conditions. The velocity profile was shown to decrease with the effect of the porosity parameter, inertial parameter, Hartmann number, and buoyancy ratio.

The Cattaneo–Christov model improves Fourier’s [31] and Fick’s [32] laws by incorporating finite propagation speeds in heat/mass transport. Christov [33] enhanced Cattaneo’s framework [34] by modifying the temporal derivative to the Oldroyd upper-convective derivative and added a relaxation time parameter [35] to describe flux delay. This technique efficiently simulates inertial effects by combining material derivative and relaxation dynamics. Applications include the Fatima et al. [36] study examining hybrid nanofluids with variable viscosity, and based on the results, the hybrid nanofluid has a significantly higher temperature profile than standard nanofluids, and the Khan et al. [37] analysis of second-grade fluids in Darcy–Forchheimer porous media, which both use the Cattaneo–Christov theory to characterise heat/mass transport. Mondal and Sibanda [38] addressed the formation of entropy via a Sakiadis nanofluid flowing onto a moving plate dictated by a magnetic field, employing the Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model to better describe heat transmission, and the results show that entropy generation increases with an increase in the Reynolds number. Their research aimed to understand how thermal relaxation time affects the flow in the boundary layer. Magodora et al. [39] studied radiative hydromagnetic nanofluid flow between parallel plates, using spectral quasi-linearisation and incorporating the Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model to capture heat transfer effects. Agbaje et al. [40] investigated free convection of micro-polar hybrid nanofluid past a permeable stretched surface with inertial drag and irregular heat generation/absorption, employing the Cattaneo–Christov model. The results highlighted the link between thermal relaxation and microchannel effects, revealing the hybrid nanofluid’s heat transport abilities. As per existing studies, the combined impacts pertaining to second-grade viscoelasticity, hybrid nanoparticles (Al2O3 − Cu/H2O), Darcy–Forchheimer drag, Cattaneo–Christov heat/mass transport, and gyro-tactic bio-convection have not been reported. Waqa et al. [41] studied the bioconvective Micropolar Casson Cross nanofluid (MCC NF) flow along a stretching sheet, developing the temperature model using the Cattaneo–Christov framework. Muhammad et al. [42] investigated the flow of a non-Newtonian nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms over a stretching surface, accounting for magnetic effects and thermal radiation, with the Cattaneo–Christov model employed to analyse the flow characteristics. Shalini et al. [43] analysed bio-thermal convection and MHD flow with gyrotactic microorganisms and nanoparticles, using the Cattaneo–Christov model and considering magnetic effects, bio-convection, and slip conditions over a porous, radiative stretching surface.

Numerical methods for flow problems have gained importance due to their wide scientific applications. Many fluid dynamics problems involve nonlinear boundary value equations that are tough to solve with traditional analytical methods. The spectral quasilinearization method (SQLM) combines iterative linearisation with spectral collocation for efficient, accurate solutions [44,45]. The SQLM outperforms finite difference, Runge–Kutta, and shooting methods in convergence and stability for smooth problems [46,47]. It has been applied to heat transfer, nanofluids, magnetohydrodynamics, and porous media flows [47,48,49,50]. Other recent applications of SQLM in nonlinear fluid dynamics can be found in [51,52,53,54].

In the present paper, a numerical analysis of bioconvective transport in a second-grade hybrid nanofluid is carried out utilising the Cattaneo–Christov heat and mass flux models in a Darcy–Forchheimer porous medium, extending previous studies. To account for finite propagation speeds, the classical Fourier and Fick laws are modified using the Cattaneo–Christov fluxes. Unlike the standard laws, which assume instantaneous response to temperature and concentration gradients, these models introduce thermal and solutal relaxation times that delay heat and mass fluxes. Physically, this means that temperature and concentration changes require a finite time to produce fluxes. Additionally, second-grade hybrid nanofluids exhibit viscoelastic behaviour, as indicated by the normal stress coefficients and . These coefficients account for the elastic response that results from the fluid’s deformation history. The integration of hybrid nanoparticles enhances the fluid’s viscosity, density, and thermal conductivity, resulting in improved momentum, heat, and mass transmission. These modifications make the model more realistic for multifaceted flows which incorporate porous media, bio-convection, and non-Fourier heat and mass transfer. Originality underpins the combination, in a single model, of a number of complex effects, namely, second-grade fluid behaviour, hybrid nanoparticles, non-Fourier and non-Fickian relaxation processes, nonlinear porous-medium drag, and bio-convection caused by gyrotactic microorganisms. No previous study has examined all these mechanisms together. The governing equations are solved via the spectral quasilinearisation method, which guarantees a high order of accuracy and strong numerical stability. The structure of the remainder of the paper is as follows: the problem is mathematically formulated in Section 2, the solution methodology is explained in Section 3, and the results are discussed in Section 4, while the conclusions are summarised in Section 5.

2. Mathematical Formulation

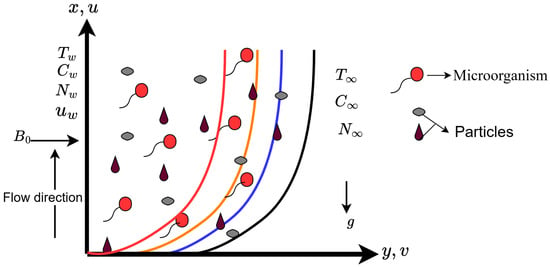

In this work, we investigate the steady, incompressible, two-dimensional bio-convective flow of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid across a linearly stretching sheet. The heat and mass transfer phenomena are modelled using the Cattaneo–Christov constitutive equations, which incorporate thermal relaxation effects. The base fluid is water, containing suspended nanoparticles and gyrotactic microorganisms, flowing through a porous medium described by the Darcy–Forchheimer model to account for both viscous and inertial resistance. The stretching velocity of the surface is defined by , where x and y represent the coordinates along and normal to the surface, respectively, as depicted in the accompanying Figure 1. The velocity components in the x- and y-directions are denoted by u and v, respectively. The temperature field is represented by T, with and corresponding to the temperatures at the surface and in the ambient region. Nanoparticle concentration is denoted by C, with and indicating the values at the surface and far field, respectively. Similarly, the concentration of microorganisms is represented by at the surface and in the free stream. A uniform magnetic field of strength is applied perpendicular to the flow direction, aligned with the y-axis.

Figure 1.

Physical representation of the problem [30].

The stress tensor, , is expressed as:

where and represent elements of the second-grade stress operator, defined as:

Here, and are material constants, represents the temporal derivative, and P denotes the pressure. The material properties are subject to the subsequent conditions for the second-grade fluid conceptualisation [55]:

The fundamental equations governing mass, momentum, energy, concentration, and microorganisms in second-grade hybrid nanofluids are as follows [56,57,58,59,60]:

where

where

Applying the relevant boundary constraints:

The velocity vectors u and v are in the x- and y-directions, (free stream velocity), (permeability of porous medium), (Non-uniform inertia coefficient), (drag coefficient), (magnetic field strength), b (tumbling frequency), and (average swimming speed).

According to the Rosseland approximation [61], we have

The mean absorption coefficient is , and is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. For small temperature variations in the boundary layer, can be approximated linearly. Expanding around and ignoring higher terms gives . Thus, Equation (9) becomes:

For the proposed fluid problem, we utilised the similarity variables as:

Here, and , with as the stream function. Using the similarity transform, Equation (4) is satisfied automatically, and Equations (5)–(8) become:

with dimensionless boundary constraints,

Here, corresponds to the wall, where the velocity, temperature, concentration, and microorganism density are prescribed. The far-field conditions () enforce ambient values and zero velocity gradients, ensuring that the flow, thermal, and concentration boundary layers vanish at infinity. These conditions are implemented directly in the spectral quasilinearisation method to accurately capture the boundary layer behaviour of the hybrid nanofluid, and

Nevertheless, the closed-form solution to Equation (12) may be derived by applying the conditions outlined in (13). The exact solution [62,63] of Equation (12) with the corresponding conditions in Equation (13) is described by the preceding equation when :

Here, denotes the elastic parameter. The velocity components can be derived from Equation (14) as follows:

When , the equation yields an explicit solution of , whereas in the general case, an appropriate mathematical formulation is required to obtain the solution. It follows that the flow equation described by Equation (12), together with the boundary constraints in Equation (13), does not admit a unique solution. Specifically, an exponential-type solution arises when , while for , the solution involves exponential terms combined with sine and cosine functions [62]. Nonetheless, for , the solution expressed in Equation (16) is the only possible and physically meaningful one, offering good physical insight into the flow behaviour. Further information can be found in the existing body of work [63].

The function is frequently used in heat transfer problems because of its practical relevance and effectiveness. In Equation (16), the viscoelastic parameter has a positive effect on the velocity component .

The evolving parameters are as follows:

where are, respectively, the second-grade parameter, magnetic parameter, mixed convection parameter, buoyancy ratio parameter, bio-convection Rayleigh number, Darcy parameter, inertial coefficient, Prandtl number, thermal radiation parameter, Eckert number, thermal relaxation parameter, Schmidt number, concentration relaxation parameter, Peclet number, Lewis number, and density ratio of the microorganisms. The thermophysical attributes of the hybrid nanofluid [64] are outlined in Table 1, while the numerical values used in the simulations [65] are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Thermophysical characteristics of hybrid nanofluids [64].

Table 2.

Computed values of thermophysical qualities of the base fluid with nano-sized particles [65].

Here, signifies the combined fractional volume of nanoscale particles, and , , and refer to the characteristics of the base fluid (H2O), alumina oxide nanoscale particles (Al2O3), and copper nanoparticles (Cu), respectively.

The hybrid nanofluid consists of Cu and Al2O3 nanoparticles distributed in water, chosen for their opposing thermophysical properties. While copper has good thermal conductivity to aid in heat transfer, Al2O3 has moderate conductivity and strong stability. Table 2 contains the numbers utilised in the mixture formulas of Table 1 to calculate effective viscosity, density, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity. The obtained parameters are fed into the Cattaneo-Christov and Darcy-Forchheimer models, which capture the unique impacts of both nanoparticles in the governing equations.

The central physical properties studied are the skin friction coefficient , Nusselt number , Sherwood number , and wall flux of motile microorganisms , which are defined by the following expressions:

The quantities , , , and denote the wall shear stress, heat transfer rate, mass transfer rate, and motile microorganism flux, correspondingly, and are denoted by:

The skin friction coefficient , Nusselt number , Sherwood number , and motile microorganism density number are denoted as:

Thus the Reynolds number is .

3. Numerical Scheme

The nonlinear system of ODEs Equation (12) are linearised by implementing the QLM, expanding nonlinear terms by a Taylor series. This yields linear equations solved iteratively [44]. The scheme is

with boundary conditions

Here, r indexes the previous iterate and the current iterate. Choose initial guesses satisfying the boundary data: and .

Coefficients:

We solve the linearised system iteratively for using the Chebyshev spectral collocation. Mapping to by and approximate the fields at Gauss–Lobatto points

( points). Derivatives of follow:

with the Chebyshev differentiation matrix and . Similarly,

Let the diagonal matrices be

Substituting Equations (27) and (28) into Equations (22)–(26) gives

with

We impose the boundary conditions as:

Then, we obtain the following:

Here, , and are diagonal matrices with and being the identity and zero matrices of size . System (36) may now be written in the form

where the matrix is of size and the vectors and are size . The approximate solutions are found by solving Equation (38) as

where is the inverse of the matrix.

4. Results and Discussion

The present study investigates the bio-convective movement of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid along a stretching surface, incorporating the effects of the Cattaneo–Christov model and Darcy–Forchheimer phenomena. To generate the results, we use SQLM in MATLAB 2022b. For the computed analysis, the following parametric values were considered:

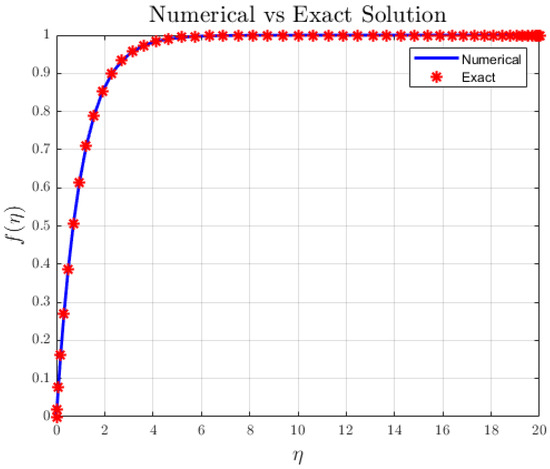

These values are assumed based on previous studies [13,28,66,67] to ensure consistency with established literature. To assess the reliability and convergence of the numerical scheme, residual errors were computed for different numbers of collocation points at the 10th iteration. As shown in Table 3, the residuals decrease rapidly with increasing grid points, demonstrating strong convergence and confirming the numerical accuracy of the solutions. To verify the accuracy of our computations, the numerical values of and were compared with previously published results. Table 4 compares for different magnetic parameter values (M) with the results of Jalil et al. [68] and Ali et al. [28] under the conditions . Table 5 compares for different Prandtl numbers () with Waini et al. [69] and Alessa et al. [70], for . As seen in both tables, the present results are in excellent agreement with the published values, with negligible differences, confirming the reliability and accuracy of the spectral quasilinearisation method. Figure 2 shows that the exact solution given in Equation (14) is in excellent agreement with the approximate solution.

Table 3.

Residual error norm for varying number of collocation points N.

Table 4.

Comparing the several values of for different M values, when .

Table 5.

Comparison of with published results Waini et al. [69] and Alessa et al. [70] across different values with .

Figure 2.

Approximate solution vs. exact solution.

Table 6 shows how various physical parameters influence the fluid flow and transport properties in a second-grade nanofluid system. The table presents quantities of the skin friction coefficient , temperature gradient , concentration gradient , and microorganism motile gradient under different parameter settings. Rising values of the second-grade parameter () cause increased resistance to flow, as reflected by the more negative . This is accompanied by slight decreases in , , and , suggesting that fluid elasticity tends to suppress thermal and species transport near the wall. An analogous trend is seen with the magnetic field parameter (M), which increases flow resistance but slightly enhances heat transfer, likely due to magnetic heating effects, while slightly reducing mass and microorganism diffusion. The inertial coefficient () and Darcy parameter (K) both reduce all transport rates when increased, indicating that higher inertia and reduced permeability hinder flow and suppress transport. Increases in the bio-convection Rayleigh number () also lower all surface gradients, suggesting that stronger microorganism buoyancy disrupts the boundary layer structure. Lastly, variations in the thermal and concentration relaxation parameters ( and ) show negligible effects on the outcome, implying that relaxation times have minimal influence under the given flow conditions.

Table 6.

Numerical results for , , , and corresponding to various parameter sets.

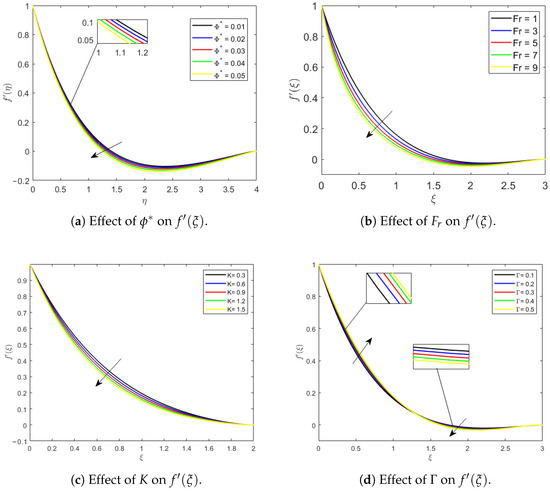

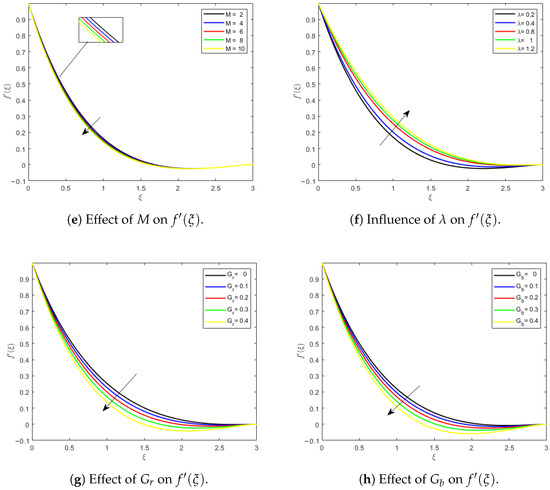

4.1. Velocity Profile

Figure 3a–h display how different factors influence the fluid velocity distributions. Figure 3a illustrates the role of on the velocity profile . Observations indicate that increasing the nanoparticle concentration causes a slight decline in fluid velocity near the boundary. This phenomenon is primarily driven by the increase in effective viscosity and density of the hybrid nanofluid, which introduces additional resistance to flow. Although the general profile remains similar, the momentum boundary layer becomes marginally thicker with increasing , indicating a subtle modulation of the flow dynamics by the nanoparticles. Physically, this occurs because the nanoparticles increase resistance near the surface, causing the fluid to slow down, while the outer layers are less affected. Figure 3b illustrates how the Forchheimer inertial parameter affects the behaviour of the velocity. With increasing , the flow through the porous medium gets more turbulent. For hybrid nanofluids, increasing the Forchheimer inertial parameter causes a decrease in flow velocity. Figure 3c illustrates the contribution of the Darcy parameter K on the velocity . As K increases, indicating a less permeable medium, the fluid velocity decreases more sharply near the surface. Figure 3d illustrates the role of the second-grade fluid parameter on the velocity . As seen, increasing leads to a noticeable reduction in across the domain. The first arrow, along with the magnified region around , highlights this decreasing trend in velocity with increasing , indicating that fluid elasticity (associated with the second-grade nature) resists motion more effectively. Similarly, the second arrow near shows that the velocity remains lower for higher even farther from the wall. The greater values of lead to a consistent suppression of the velocity profile, reflecting the enhanced viscoelastic resistance in second-grade fluids. Overall, these data show that the linear effects of Darcy–Forchheimer drag and the nonlinear viscoelasticity of the second-grade fluid interact to determine flow behaviour. The fluid’s elasticity increases resistance, thickening the boundary layer, while the porous-medium drag alters velocity distribution. This interaction stabilises the flow, lowering near-wall velocity variations and assuring more controlled and predictable motion across the area. Figure 3e demonstrates the impact of the magnetic parameter (M) on the velocity profile. Increasing M reduces the velocity of the second-grade hybrid nanofluid because the Lorentz force, which opposes the fluid flow, becomes stronger. This force contributes a crucial part in controlling the fluid’s movement within the system and is directly linked to the value of M. On a physical level, this means that a greater magnetic field slows fluid motion near the surface while leaving the outer layers unaffected, essentially increasing the momentum barrier layer. Figure 3f shows how the mixed convection parameter () impacts the flow rate. As increases, the flow rate goes up because of a stronger buoyancy force. At the same time, shear thinning occurs, which also helps boost the fluid’s velocity. This means that the combined impact of increased buoyancy and reduced resistance near the wall causes the fluid to accelerate, increasing momentum in the boundary layer while the outer flow adjusts gradually. Figure 3g,h illustrate how the velocity profile varies with changes in buoyancy ratio parameter () and bioconvection (). Figure 3g shows that the flow velocity drops as increases. It captures the proportional contribution of thermal and nanoparticle buoyancy. Figure 3h demonstrates that the velocity profile decreases as values grow. It is clear that heat and nanoparticle buoyancy effects dominate near the wall. Physically, a greater improves the combined impact of thermal and nanoparticle buoyancy by raising resistance near the wall and slightly slowing the fluid. Figure 3h illustrates that the velocity profile reduces as increases. This is because increased bioconvection causes more buoyant forces from motile microorganisms to counter fluid motion near the surface, resulting in a thicker momentum barrier layer and overall flow dampening.

Figure 3.

Variationin velocity profile for different physical parameters: , , K, , M, , , and .

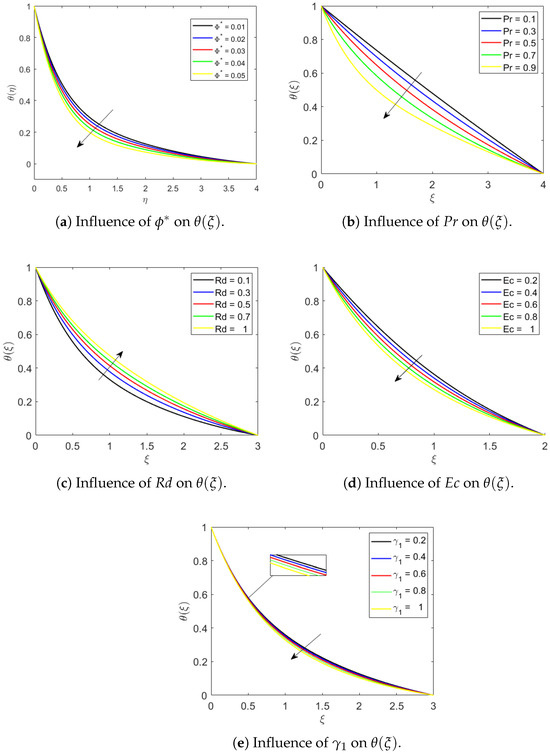

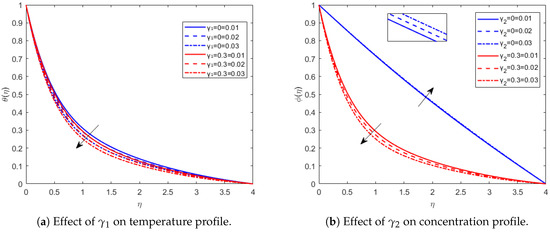

4.2. Temperature Profile

Figure 4a–e demonstrate how various flow values influence the temperature characteristics. As illustrated in Figure 4a, a climb in the total nanoparticle volume ratio , where and correspond to alumina () and copper () nanoparticles, respectively, results in a more rapid decline in the thermal profile . This behaviour results from the boosted thermal conductivity of the hybrid nanofluid, enhancing heat transfer from the surface and thus reducing the thermal near-wall layer thickness as rises. Physically, this happens because a larger nanoparticle concentration raises the hybrid nanofluid’s thermal conductivity, which improves heat transfer from the surface and thins the near-wall thermal boundary layer.

Figure 4.

Effects of parameters , , , , and on the temperature variation .

Figure 4b illustrates the impact of the Prandtl number () on the thermal profile. It clearly highlights that as rises, thermal diffusion decreases. Physically, this occurs since reflects how momentum diffusivity compares to thermal diffusivity: higher values mean thermal diffusivity is relatively lower, resulting in slower heat transfer within the fluid. Figure 4b shows that heat transport becomes less successful, resulting in a delayed dispersion of thermal energy within the fluid. This shows that the fluid’s ability to transport heat away from the surface has decreased, which can be attributable to higher thermal resistance or lower temperature gradients within the flow. Figure 4c illustrates how the parameter influences the energy curve. It shows that as increases, the thermal levels rise. This happens because a higher thermal radiation parameter means more electromagnetic waves are emitted, resulting in a greater release of thermal energy. In actuality, a rise in the thermal radiation parameter causes enhanced emission of electromagnetic waves, indicating that more thermal energy is released. As the thermal radiation aspect increases, it leads to a greater thermal distribution across the system, resulting in elevated temperatures. This demonstrates the direct link between the radiation factor and the temperature profile, emphasising how crucial radiative heat transfer is in determining the thermal distribution in the system. Figure 4d shows that as the Eckert number () increases, the temperature decreases. Although higher generally enhances viscous heating, the fluid’s elastic nature, enhanced heat conduction of the hybrid nanofluid, and thermal-relaxation effects of the Cattaneo–Christov model delay and redistribute the dissipated energy. Consequently, the generated heat is not immediately transferred into the fluid, leading to a net reduction in . It is clear that the delayed heat and mass transport associated with the Cattaneo–Christov model is responsible for the observed decrease in temperature with increasing . Figure 4e shows the effect of on temperature. When goes up, the temperature tends to drop. This behaviour implies that higher values of improve thermal diffusion, resulting in lower fluid temperature and a reduced thermal boundary layer thickness.

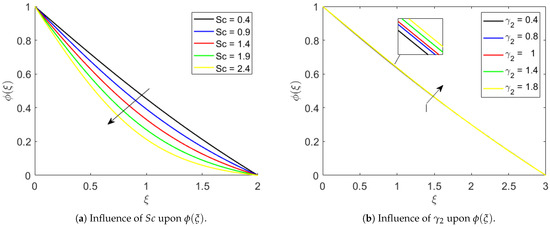

4.3. Concentration Profile

Figure 5a,b demonstrate how several factors affect the concentration profile. Figure 5a depicts how affects the concentration distribution. Physically, increasing reduces the fluid’s mass diffusivity, slowing the distribution of solute particles and keeping concentrations at the surface higher, thinning the concentration boundary layer. Figure 5b illustrates the impact of the characteristic time for concentration relaxation on the concentration profile. This shows that higher speeds concentration adjustment within the fluid, increasing the rate of species diffusion and thickening the concentration profile near the wall.

Figure 5.

Concentration variation for parameters and .

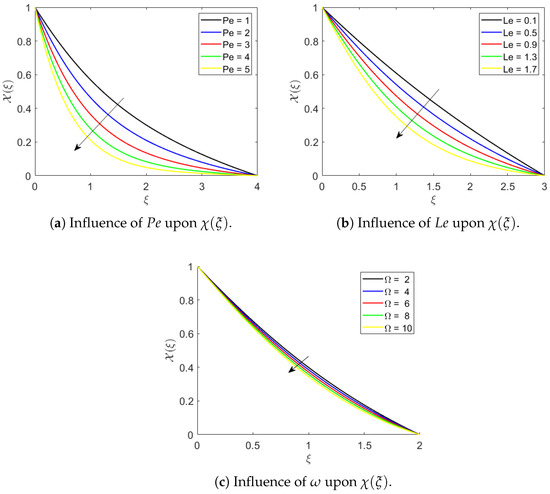

4.4. Microorganism Profile

Figure 6a–c highlight how several circumstances affect motile distribution. Figure 6a depicts the significance of the Péclet number , a crucial parameter for understanding the motion behaviour of microbes within the fluid. It denotes the fraction of the maximal cell swimming speed, microbe diffusion, and chemotaxis constant. Diffusion is the movement from higher to lower concentration, and as the Péclet number () increases, fluid velocity rises while microorganism diffusivity decreases, weakening their movement. Consequently, the micro-rotation distribution diminishes. This means that when increases, fluid velocity takes dominance over microbial diffusion, limiting microorganisms’ effective movement and near-wall density. Similarly, Figure 6b shows that as the bio-convection Lewis number () grows, the density of microorganisms decreases, resulting in lower surface concentration, reduced particle strength, diminished mass, and weaker density profiles. A larger decreases the diffusivity of microorganisms, lowering their density near the surface and diminishing the overall motile microbe profile. Furthermore, from Figure 6c, it is evident that an increasing motile microbe parameter corresponds to a decreasing trend in the motile microorganism profiles. Increasing improves microbial motility and dispersion, resulting in more uniformly distributed germs in the fluid and decreased concentration along the wall.

Figure 6.

Variation in motile micro-organisms for parameters , , and .

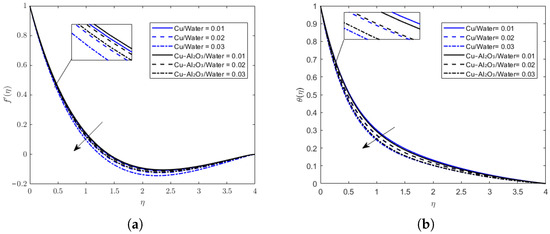

4.5. Nanofluid vs. Hybrid Nanofluid

Figure 7 clearly shows the differences between the Cu/water nanofluid and Cu-Al2O3/water hybrid nanofluids. The hybrid nanofluid promotes a higher velocity gradient near the wall than its single-nanoparticle counterpart, as shown in Figure 7a. This shows higher momentum diffusion stimulated by both copper and alumina nanoparticles for the hybrid fluid than for its single-nanoparticle counterpart. It is obvious from Figure 7b. that the hybrid nanofluid sustains higher temperature values all throughout its boundary layer. This is also expected because having hybrid nanoparticles ensures higher thermal conductivity values for enhanced heat transfer. It is also apparent that hybrid nanofluid performs better than standard nanofluids as regards hydrodynamic and thermal performances.

Figure 7.

Comparison of nanofluid vs. hybrid nanofluid profiles for and . (a) Effect of nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid on . (b) Effect of nanofluid vs hybrid nanofluid on .

4.6. Impact of Relaxation Parameters on Hybrid Nanofluid

Figure 8 illustrates the effects of thermal () and concentration () relaxation on the hybrid nanofluid profiles. Increasing the thermal relaxation parameter to results in a rise in temperature and a thicker thermal boundary layer, particularly when compared to the standard Fourier case (). Similarly, enhancing the concentration relaxation parameter to increases the nanoparticle concentration and makes the concentration boundary layer thicker relative to the classical Fick case (). There is also a slight cross-coupling effect—raising causes a modest increase in temperature. Overall, the non-classical Cattaneo–Christov model produces higher profiles and thicker boundary layers, clearly indicating that non-Fourier and non-Fickian relaxation significantly influence heat and mass transport.

Figure 8.

Profiles of temperature and concentration hybrid nanofluid.

These findings have practical significance in bioreactors, where they can enhance nutrient distribution and account for delayed thermal responses; in geothermal systems, by improving heat extraction efficiency; and in biofuel processing, by optimising temperature and concentration control. Collectively, these applications highlight the relevance of the present model beyond theoretical analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the impact of bio-convection on the flow behaviour of a second-grade hybrid nanofluid through a porous media, using Cattaneo-Christov heat and mass fluxes across a stretching sheet. We studied how various physical factors influence velocity, temperature, concentration, and the behaviour of microorganisms in the flow. We noted that

- An increase in the nanoparticle volume ratio slightly decreases the fluid velocity near the surface caused by higher viscosity and density, but it boosts heat transfer by improving thermal conductivity, resulting in quicker temperature reduction.

- Stronger inertial effects from the porous medium (Forchheimer parameter) and a stronger magnetic field reduce flow velocity by adding resistance.

- Porous medium permeability K affects flow differently: a lower K increases the surface velocity and thickens the boundary layer, while a higher K slows the near-wall flow and thins the boundary layer farther away.

- Mixed convection tends to increase flow velocity, whereas buoyancy and bioconvection effects tend to decrease it.

- Second-grade parameter increases resistance, reducing the velocity.

- Increased thermal relaxation delays heat transfer, resulting in smoother and lower temperature profiles.

- Concentration relaxation enhances concentration distribution, while a higher Schmidt number weakens concentration effects by reducing diffusion.

- Higher Peclet and Lewis numbers reduce microorganism accumulation by speeding fluid flow and dispersing microorganisms from growth zones.

- Second-grade magnetic fields, inertia, permeability, and bio-convection strongly influence transport, while thermal and concentration relaxation effects play a lesser role in this regime.

Hybrid nanofluids have better thermal conductivity and, consequently, an improved heat transfer characteristic compared with single-particle nanofluids due to the combination of nanoparticles. The advantages of hybrid nanofluids render them applicable in practical situations, including cooling systems, biomedical devices, environmental remediation, and industrial processes that involve porous media and biological activity. The present study adds to the existing understanding by capturing the combined effects of hybrid nanofluid, bio-convection, and non-Newtonian fluid behaviour in porous media. Future studies may be conducted on unsteady and three-dimensional flows with Cattaneo–Christov heat and mass flux, various hybrid or tetra-hybrid nanoparticle combinations, and further additional effects such as radiation, chemical reactions, or variable wall conditions with a view to achieving closer resemblance to reality. Applications to practical situations such as bioreactors, geothermal energy systems, and biofuel reactors, along with experimental validation and stability analysis under combined magnetic, porous, and bio-convective effects, will serve to further extend the findings herein and deliver useful insights into flow behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and S.P.G.; validation, M.P. and S.P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P., S.P.G., S.A. and L.M.; visualization, M.P. and S.A.; supervision, S.P.G. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the North-West University and University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| a | Constant |

| Cartesian coordinates | |

| Velocity components along x- and y-axis | |

| Sheet surface uniform temperature | |

| Ambient temperature | |

| Sheet surface uniform concentration | |

| Ambient concentration | |

| Sheet surface uniform microorganism | |

| Ambient microorganism | |

| Specific heat capacity | |

| Maximum cell swimming speed | |

| Mass diffusion coefficient | |

| Microorganism diffusion coefficient | |

| g | Acceleration due to gravity |

| Velocity at wall | |

| Mass transfer velocity | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Radiation parameter | |

| Schmidt number | |

| Prandtl number | |

| Eckert number | |

| Peclet number | |

| Bio-convection Rayleigh parameter | |

| Mixed convection parameter | |

| Buoyancy parameter | |

| Lewis number | |

| K | Permeability |

| Magnetic field | |

| H2O | Water |

| Al2O3 | Alumina oxide |

| Cu | Copper |

| Greek symbols | |

| Kinematic viscosity | |

| Dynamic viscosity | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Mean absorption coefficient | |

| Volume expansion coefficient | |

| Electrical conductivity | |

| Stefan–Boltzmann constant | |

| Average volume of microorganism | |

| Fluid density | |

| Second grade fluid parameter | |

| Subscripts | |

| w | Condition on surface |

| ∞ | Ambient condition |

| p | Nanoparticle |

| m | Microorganisms |

| Hybrid nanofluid | |

| f | Base fluid |

References

- Erdogan, M.E.; Imrak, C.E. On unsteady unidirectional flows of a second grade fluid. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2005, 40, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivlin, R.S.; Ericksen, J.L. Stress-deformation relations for isotropic materials. In Collected Papers of RS Rivlin: Volume I and II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 911–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.U.S. Nanofluid Technology: Current Status and Future Research; Technical Report; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 1998.

- Nisar, Z.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Ahmad, B. Mathematical modeling for peristalsis of couple stress nanofluid. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 11683–11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, S.; Berrouk, A.S. Comparative study of computational frameworks for magnetite and carbon nanotube-based nanofluids in enclosure. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 2403–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdal, S.; Mariam, A.; Ali, B.; Younas, S.; Ali, L.; Habib, D. Implications of bioconvection and activation energy on Reiner–Rivlin nanofluid transportation over a disk in rotation with partial slip. Chin. J. Phys. 2021, 73, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Q.; Qureshi, M.Z.A.; Khan, B.A.; Kadhim Hussein, A.; Ali, B.; Shah, N.A.; Chung, J.D. Insight into dynamic of mono and hybrid nanofluids subject to binary chemical reaction, activation energy, and magnetic field through the porous surfaces. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Q.; Wang, X.; Ali, B.; Qureshi, M.Z.A.; Chamkha, A.J. Heat and mass transfer phenomenon and aligned entropy generation with simultaneous effect for magnetized ternary nanoparticles induced by ferro and nano-layer fluid flow of porous disk subject to motile microorganisms. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2025, 86, 2635–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, I.; Khan, Y.; Nadeem, M.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Bilal, M. Significance of heat transfer for second-grade fuzzy hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching/shrinking Riga wedge. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Saeed, A.; Suttiarporn, P.; Khan, W.; Kumam, P.; Watthayu, W. Analysis of second grade hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching flat plate in the presence of activation energy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Siddique, I.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Bilal, M. Numerical analysis of a second-grade fuzzy hybrid nanofluid flow and heat transfer over a permeable stretching/shrinking sheet. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.; Nasr, E.; Ahmed, K.K.; Emadifar, H.; Ahmed, H.M.; Alkhatib, S. Hybrid nanofluids and bioconvection: Insights into bacterial behavior and particle interaction. Bound. Value Probl. 2025, 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Jawad, M.; Nasir, F.; Ali, I. Influences of Gyrotactic Microorganisms and Nonlinear Mixed Bio-Convection on Hybrid Nanofluid Flow over an Inclined Extending Plate with Porous Effects. J. Heat Mass Transf. Res. 2024, 11, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Mustafa, Z.; Siddique, I.; Ajmal, M.; Jaradat, M.M.; Rehman, S.U.; Ali, B.; Ali, H.M. Computational analysis for bioconvection of microorganisms in prandtl nanofluid darcy–forchheimer flow across an inclined sheet. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, H.; Khan, S.U.; Hassan, M.; Bhatti, M.; Imran, M. Analysis on the bioconvection flow of modified second-grade nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms and nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 291, 111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshomrani, A.S. Numerical investigation for bio-convection flow of viscoelastic nanofluid with magnetic dipole and motile microorganisms. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 5945–5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Khan, M.I.; Khan, N.B.; Kadry, S.; Khan, S.U.; Tlili, I.; Nayak, M. Significance of activation energy, bio-convection and magnetohydrodynamic in flow of third grade fluid (non-Newtonian) towards stretched surface: A Buongiorno model analysis. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 118, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Chutia, B. Dusty nanofluid flow with bioconvection past a vertical stretching surface. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2022, 34, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdows, M.; Zaimi, K.; Rashad, A.M.; Nabwey, H.A. MHD bioconvection flow and heat transfer of nanofluid through an exponentially stretchable sheet. Symmetry 2020, 12, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Farooq, M.A.; Mushtaq, A.; Shamsi, Z.H. Unsteady MHD bionanofluid flow in a porous medium with thermal radiation near a stretching/shrinking sheet. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8822999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S.; Shah, Q.; Bhaumik, A.; Kumam, P.; Thounthong, P.; Amiri, I. Entropy generation in bioconvection nanofluid flow between two stretchable rotating disks. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.S.; Nasr, E.H.; Mabrouk, S.M. Influence of gyrotactic microorganisms on bioconvection in electromagnetohydrodynamic hybrid nanofluid through a permeable sheet. Computation 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Aneja, M.; Ashraf, M.B.; Nawaz, R. Bioconvection heat and mass transfer across a nonlinear stretching sheet with hybrid nanofluids, joule dissipation, and entropy generation. ZAMM-J. Appl. Math. Mech. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 2024, 104, e202300550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, H. The Public Fountains of the City of Dijon; Experience and Application: Paris, France, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Forchheimer, P. Wasserbewegung. Ver. Dtsch. Ing. 1901, 45, 1782–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Muskat, M. The Flow of Homogeneous Fluids Through Porous Media; JW Edwards: London, UK, 1946; Volume 273. [Google Scholar]

- Enamul, S.; Ontela, S. Magnetohydrodynamic Darcy-Forchheimer flow of non-Newtonian second-grade hybrid nanofluid bounded by double-revolving disks with variable thermal conductivity: Entropy generation analysis. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 6, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Abbas, S.T.; Sohail, M.; Singh, A. Study of bioconvection phenomenon in Jefferey model in a Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 4666–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Ali, M.H.; Abodayeh, K.; Abbas, S.T. Bio-convective boundary layer flow of Maxwell nanofluid via optimal homotopic procedure with radiation and Darcy-Forchheimer impacts over a stretched sheet. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2025, 46, 2462583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algehyne, E.A.; Areshi, M.; Saeed, A.; Bilal, M.; Kumam, W.; Kumam, P. Numerical simulation of bioconvective Darcy Forchhemier nanofluid flow with energy transition over a permeable vertical plate. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourier, J.B.J. Théorie Analytique de la Chaleur; Gauthier-Villars et fils: Paris, France, 1888. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, A. On liquid diffusion. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 100, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christov, C. On frame indifferent formulation of the Maxwell–Cattaneo model of finite-speed heat conduction. Mech. Res. Commun. 2009, 36, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C. Sulla conduzione del calore. Atti Sem. Mat. Fis. Univ. Modena 1948, 3, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, R.P.; Kumar, R.N.; Kumar, R.; Prasannakumara, B. Three-dimensional coupled flow and heat transfer in non-Newtonian magnetic nanofluid: An application of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 567, 170329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Ghodhbani, R.; Majeed, A.; Ijaz, N.; Saleem, N. Thermodynamics of Cattaneo–Christov heat flux theory on hybrid nanofluid flow with variable viscosity, convective boundary, and velocity slip. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Saeed, M.; Hashmi, M.; Inc, M. Darcy–Forchheimer flow of second-grade fluid in a porous medium using Cattaneo–Christov model. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 37, 2350125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.; Sibanda, P. Spectral quasi-linearization method for entropy generation using the Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2020, 17, 1940002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magodora, M.; Mondal, H.; Sibanda, P. Dual solutions of a micropolar nanofluid flow with radiative heat mass transfer over stretching/shrinking sheet using spectral quasilinearization method. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 2020, 16, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, T.M.; Panda, S.; Mishra, S.; Baithalu, R. Free convection of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model for the micropolar hybrid nanofluid through permeable stretching surface with inertial drag and irregular heat sink/source. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2025, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, H.; Imran, M.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, I.; Pasha, A.A.; Irshad, K. Cattaneo–Christov double diffusion and bioconvection in magnetohydrodynamic three-dimensional nanomaterials of non-Newtonian fluid containing microorganisms with variable thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity. Waves Random Complex Media 2025, 35, 5759–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M.; Islam, S.; Ullah, H.; Dawar, A.; Shah, Z. A semi-analytical strategy for mixed convection non-Newtonian nanofluid flow on a stretching surface using Cattaneo-Christov model. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16, 16878132241245833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, C.A.; Ganteda, C.; Reddy, G.R.; Maheswari, B.U.; Kokila, G.; Govindan, V.; Byeon, H.; Praveenkumar, S.; Pimpunchat, B. Numerical simulation of unsteady MHD bio-convective flow with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux over a stretching surface. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 68, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R.E.; Kalaba, R.E. Quasilinearization and Nonlinear Boundary-Value Problems; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Trefethen, L.N. Spectral Methods in MATLAB; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Motsa, S.S.; Dlamini, P.G.; Khumalo, M. Spectral relaxation method and spectral quasilinearization method for solving unsteady boundary layer flow problems. Adv. Math. Phys. 2014, 2014, 341964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magodora, M.; Mondal, H.; Sibanda, P. Effect of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux on radiative hydromagnetic nanofluid flow between parallel plates using spectral quasilinearization method. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2022, 8, 865–875. [Google Scholar]

- Sithole, H.; Mondal, H.; Goqo, S.; Sibanda, P.; Motsa, S. Numerical simulation of couple stress nanofluid flow in magneto-porous medium with thermal radiation and a chemical reaction. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 339, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goqo, S.P.; Mondal, S.; Sibanda, P.; Motsa, S.S. An unsteady magnetohydrodynamic Jeffery nanofluid flow over a shrinking sheet with thermal radiation and convective boundary condition using spectral quasilinearisation method. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2016, 13, 7483–7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedai, S.; Sibanda, P.; Goqo, S.P.; Noreldin, O.A. Numerical computational model for an unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium past an MHD rotating sheet. Nonlinear Eng. 2025, 14, 20220368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, T.M.; Baithalu, R.; Mishra, S.; Panda, S. Irreversibility processes on the squeezing flow analysis of blood-based micropolar hybrid nanofluid through parallel channel: Spectral quasilinearisation method. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 3226–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshuddin, M.; Agbaje, T.; Asogwa, K.; Ramesh, K. Computational investigation for silica-molybdenum disulfide/water-based hybrid nanofluid over an exponential stretching sheet with spectral quasi-linearization method. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. 2025, 86, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Sugunamma, V.; Narla, V.K. Biomagneto-Hydrodynamic Williamson Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer Over a Stretching Surface: A Spectral Quasi-Linearization Approach. East Eur. J. Phys. 2025, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, T.M.; Folarin, O.; Mishra, S.; Baithalu, R.; Panda, S. Spectral quasilinearization with overlapping grid technique for the flow of time-dependent conducting nanofluid over a circular disk. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Khan, M.; Ayub, M. Some analytical solutions for second grade fluid flows for cylindrical geometries. Math. Comput. Model. 2006, 43, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, G.K. An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Z.; O. Alzahrani, E.; Dawar, A.; Alghamdi, W.; Zaka Ullah, M. Entropy generation in MHD second-grade nanofluid thin film flow containing CNTs with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model past an unsteady stretching sheet. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, M.; Saeed, A.; Tassaddiq, A.; Khan, A.; Gul, T.; Kumam, P.; Shah, Z. Insight into the dynamics of second grade hybrid radiative nanofluid flow within the boundary layer subject to Lorentz force. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, T.; Shah, F.; Hussain, Z.; Alsaedi, A. Outcomes of double stratification in Darcy–Forchheimer MHD flow of viscoelastic nanofluid. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed Khan, N.; Shah, Q.; Sohail, A. Dynamics with Cattaneo–Christov heat and mass flux theory of bioconvection Oldroyd-B nanofluid. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1687814020930464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhukesh, J.; Ramesh, G.; Prasannakumara, B.; Shehzad, S.; Abbasi, F. Bio-Marangoni convection flow of Casson nanoliquid through a porous medium in the presence of chemically reactive activation energy. Appl. Math. Mech. 2021, 42, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajravelu, K.; Roper, T. Flow and heat transfer in a second grade fluid over a stretching sheet. Int. J. -Non-Linear Mech. 1999, 34, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, H.; Reddy, G.J.; Abhishek; Killead, A.; Pujari, V.; Kumar, N.N. Numerical modelling of second-grade fluid flow past a stretching sheet. Heat Transf. Asian Res. 2019, 48, 1595–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Venkitaraj, K.; Selvakumar, P.; Chandrasekar, M. Synthesis of Al2O3–Cu/water hybrid nanofluids using two step method and its thermo physical properties. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2011, 388, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Hussein, A.K.; Mansour, M.; Raizah, Z.A.; Zhang, X. MHD mixed convection in trapezoidal enclosures filled with micropolar nanofluids. Nanosci. Technol. Int. J. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, I.; Nadeem, M.; Ali, R.; Jarad, F. Bioconvection of MHD second-grade fluid conveying nanoparticles over an exponentially stretching sheet: A biofuel applications. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 3367–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramar, A.; Sudarmozhi, K.; Selvi, P.; Akanni, J.O. Numerical analysis of hybrid nanofluid flow over a sheet with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.; Asghar, S.; Yasmeen, S. An exact solution of MHD boundary layer flow of dusty fluid over a stretching surface. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 2307469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waini, I.; Ishak, A.; Pop, I. Unsteady flow and heat transfer past a stretching/shrinking sheet in a hybrid nanofluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 136, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, N.; Sindhu, R.; Divya, S.; Eswaramoorthi, S.; Loganathan, K.; Prasad, K.S. Computational analysis of Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Cu/Al–Al2O3 hybrid nanofluid in water over a heated stretchable plate with nonlinear radiation. Micromachines 2023, 14, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).