An Inventory Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality, Deterioration, and Freshness- and Inventory Level-Dependent Demand Under Carbon Emissions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Notations, Assumptions and Model Development

3.1. Notations

3.2. Assumptions

- The inventory system starts with a quantity y of a growing item, and the replenishment cycle occurs at fixed time intervals T.

- The slaughtered items are immediately inspected and prepared for sale to consumers.

- The slaughtered items have a maximum shelf life of L time units, which constrains the inventory replenishment cycle duration to be less than this lifetime (i.e., ).

- A 100% inspection is performed on the entire batch at a screening rate x to separate the products based on their quality into ’good’ and ’bad’ products.

- A percentage of the slaughtered items are of imperfect quality.

- Good quality products are sold at a price .

- All imperfect-quality products are collected and sold together as a single batch at the end of the inspection procedure at a price .

- The freshness function for the product is deterministic and is dependent on the shelf life L of the slaughtered items as follows:

- The inventory is at its peak freshness immediately after slaughter and delivery to the customer, with at . The product then deteriorates over time, reaching its expiration date at when . To maintain product quality, the retailer’s inventory cycle time T must be less than the expiration date L.

- The demand for the product is deterministic and is dependent on the level of the current inventory and its freshness as follows:where and .

- The inventory is subject to a physical deterioration, , and it is a time-dependent function represented by the following exponential function:

- Deteriorated items are not repairable and, therefore, are discarded to reflect the impact of cost and emissions processing these items.

- The shortages are not permitted.

- The inventory purchasing, holding, and ordering activities result in the release of carbon emissions.

- Carbon tax policies are implemented as a regulatory measure to reduce emissions.

4. Mathematical Model

4.1. Total Cost Function (TCF)

4.1.1. Feeding Cost per Cycle

Feeding Cost per Cycle

4.1.2. Holding Cost of the Good Product

4.1.3. Holding Cost of the Imperfect Product

4.1.4. Deterioration Cost

4.1.5. Screening Cost

4.1.6. Purchasing Cost of the Product

4.1.7. Ordering Cost

4.1.8. Carbon Emissions Costs

4.2. Total Revenue Function (TRF)

4.3. Total Profit per Unit of Time (TPU)

4.3.1. Model Constraint

4.3.2. Mathematical Formulation of the EOQ Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality and Carbon Emissions

4.3.3. Computational Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Proposed step-by-step algorithm |

5. Numerical Example and Sensitivity Analysis

5.1. Numerical Example

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

- As shown in Figure 5, the optimal cycle length is

- –

- Highly sensitive to parameters b, L, , , , , , and ;

- –

- Moderately sensitive to changes in , h, , and ;

- –

- Insensitive to variations in a, , , x, and K.

- Figure 6 shows that the optimal lot size is

- –

- Highly sensitive to parameters b, , L, and ;

- –

- Moderately sensitive to changes in , , , , and ;

- –

- Insensitive to other parameters including , h, a, , , , , , , x, , , and K.

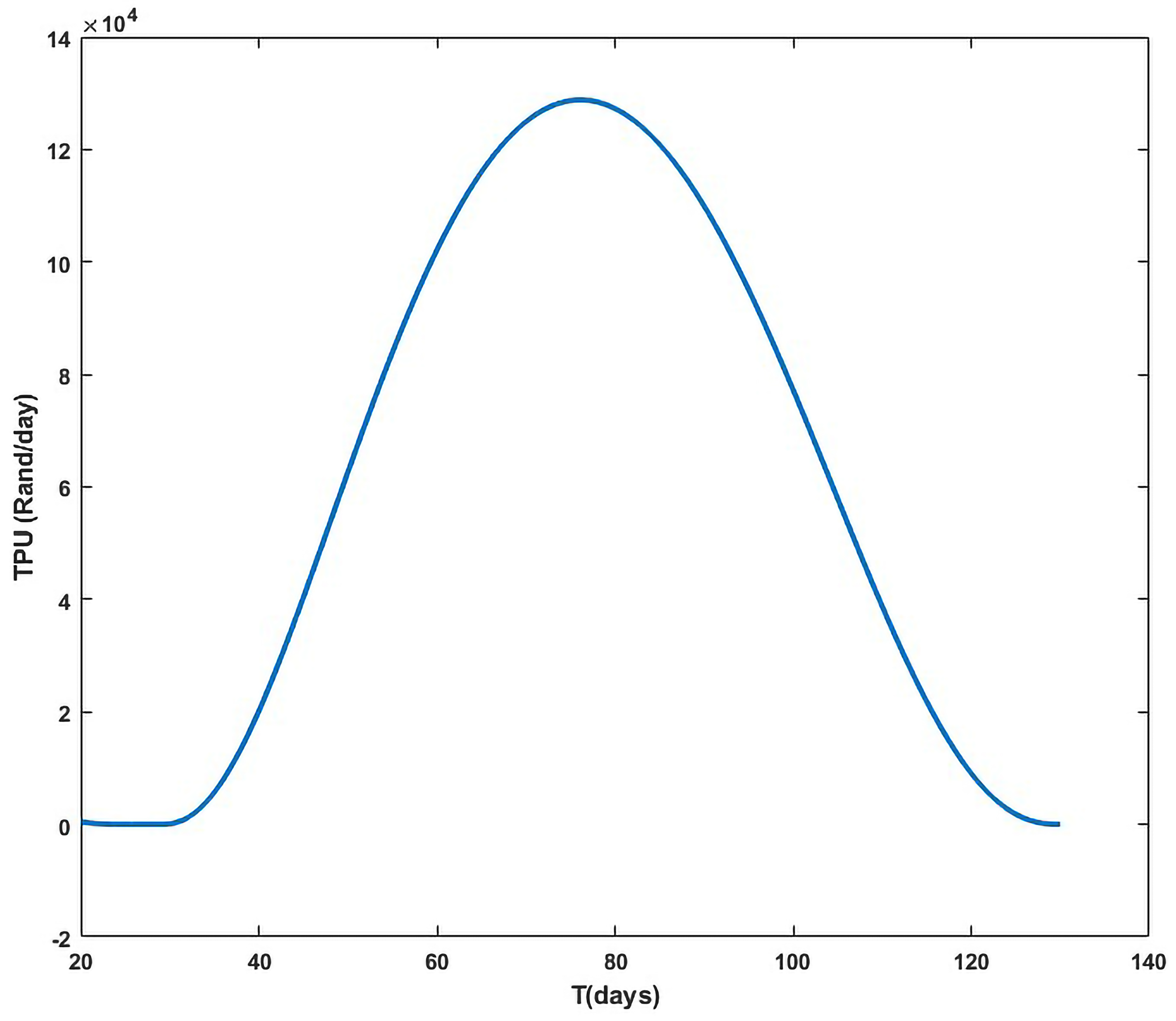

- The behaviour of the total profit per unit time , detailed in Figure 7, indicates

- –

- High sensitivity to parameters , L, , b, A, , , , , , and ;

- –

- Moderate sensitivity to changes in x, h, , , , , , and ;

- –

- Insensitivity to , , , , , , and K.

5.3. Managerial Insights

- 1.

- Parameter L has the most significant impact on T performance, with L showing substantial positive influence when it increases and notable negative effects when it decreases. Managers should opt for longer expiration dates (shelf lives).

- 2.

- Parameter b demonstrates strong asymmetric sensitivity, with a positive influence when it increases and minimal negative impact when it decreases. This suggests that increasing b within controlled limits can significantly enhance T performance without substantial downside risk. Production managers should optimise this parameter to maximise the system output while maintaining operational stability.

- 3.

- Parameters b and L have the most critical impact on performance, with b showing both positive and negative effects. Managers should optimise this parameter and use real-time monitoring to ensure optimal batch size y performance. L also shows similar behaviour. This suggests that the shelf life, L, is also a fundamental driver of the batch size, y.

- 4.

- The weight, , of each grown item at the time of slaughtering shows significant impacts on y. When , the optimal order quantity, increases, y decreases significantly. This is because a higher implies a longer growth cycle; to meet a fixed total weight target for the market, fewer items are required. Managers should, therefore, reduce their initial order quantity (y) when aiming to raise them to a higher slaughter weight.

- 5.

- The total profit per time decreases significantly as increases. This is because the operational costs of sustaining inventory, including feeding cost consumption, carbon emissions costs, and inventory holding costs over the growth period, increase at a rate that surpasses the revenue from the increase in weight . To optimise financial performance, managers should identify a weight that prioritises a fast turnover rate. Slaughtering items at this weight minimises the period during which they incur high costs, thus prioritising efficiency.

- 6.

- Managers should also aim for a longer shelf life L as well as a faster growth rate , as longer shelf life allows more time for management to optimise sales, thereby protecting profit margins. A longer shelf life reduces the risk of spoilage within a cycle, allowing managers to capitalise on economies of scale by placing larger, less frequent orders. With a product that remains fresh for longer, the retailer can safely lengthen the replenishment cycle without compromising quality. This reduces ordering costs. A faster growth rate acts as a force multiplier, significantly increasing the system throughput and revenue without requiring capital expansion.

- 7.

- The analysis of Table A1 reveals that strategically differentiating emissions sources offers a clear path to enhance sustainability and boost profitability. The most impactful opportunity lies within the feeding period, where reducing emissions offers substantial improvements, creating an increase in profit. In contrast, emissions associated with inventory inspection, storage, or spoilage hold surprisingly minimal financial or operational implications. Therefore, to master the profit sustainability dynamic, organisations should strategically prioritise investments into innovating the feeding process and optimising purchasing strategies, as these are the cornerstones for a more profitable and sustainable operation.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| % Change | T | EOQ (y) | TPU | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | % Change | Items | % Change | ZAR/Day | % Change | ||

| Base | 76.16 | 1369 | 128,810 | ||||

| A | −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 25,237.21 | −80.4% |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 43,399.89 | −66.3% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 66,986.04 | −48.0% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 95,702.04 | −25.7% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 165,110.3 | 28.2% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 202,864.6 | 57.5% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 239,749.2 | 86.1% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 272,794 | 111.8% | |

| b | −50.0% | 75.17 | −1.3% | 6 | −99.5% | 774.6 | −99.4% |

| −37.5% | 75.39 | −1.0% | 16 | −98.8% | 1862.89 | −98.6% | |

| −25.0% | 75.61 | −0.7% | 48 | −96.5% | 5533.26 | −95.7% | |

| −12.5% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 203 | −85.2% | 22,139.62 | −82.8% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 107.65 | 41.3% | 6404 | 367.6% | 284,107 | 120.6% | |

| +25.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| +37.5% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| +50.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| −50.0% | 87.05 | 14.3% | 1307 | −4.5% | 114,175.9 | −11.4% | |

| −37.5% | 84.86 | 11.4% | 1345 | −1.8% | 115,425.4 | −10.4% | |

| −25.0% | 82.32 | 8.1% | 1373 | 0.3% | 118,026.2 | −8.4% | |

| −12.5% | 79.35 | 4.2% | 1384 | 1.1% | 122,382.2 | −5.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.15 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 73.07 | −4.0% | 1330 | −2.9% | 137,321.6 | 6.6% | |

| +25.0% | 70.54 | −7.4% | 1279 | −6.6% | 147,573.7 | 14.6% | |

| +37.5% | 68.67 | −9.8% | 1232 | −10.0% | 159,103.6 | 23.5% | |

| +50.0% | 67.13 | −11.8% | 1188 | −13.3% | 171,518.1 | 33.2% | |

| −50.0% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 129,380.4 | 0.4% | |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,237.9 | 0.3% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,101.2 | 0.2% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,953.2 | 0.1% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,668.4 | −0.1% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,526 | −0.2% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,383.6 | −0.3% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,241.2 | −0.4% | |

| −50.0% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 130,717.9 | 1.5% | |

| −37.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 130,241 | 1.1% | |

| −25.0% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 129,764.2 | 0.7% | |

| −12.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 129,287.3 | 0.4% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,334.2 | −0.4% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,857.7 | −0.7% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,381.2 | −1.1% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,904.7 | −1.5% | |

| −50.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| −37.5% | 89.92 | 18.1% | 510 | −61.6% | 18,660.5 | −85.5% | |

| −25.0% | 85.2 | 11.9% | 804 | −39.5% | 48,527 | −62.3% | |

| −12.5% | 79.35 | 4.2% | 1079 | −18.8% | 87,128.99 | −32.4% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1328 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 73.51 | −3.5% | 1548 | 16.6% | 170,907.3 | 32.7% | |

| +25.0% | 71.42 | −6.2% | 1744 | 31.3% | 211,927.9 | 64.5% | |

| +37.5% | 69.66 | −8.5% | 1915 | 44.2% | 251,104 | 94.9% | |

| +50.0% | 68.28 | −10.3% | 2070 | 55.8% | 288,090.1 | 123.7% | |

| L | −50.0% | 46.03 | −39.6% | 45 | −96.7% | 6334.45 | −95.1% |

| −37.5% | 53.55 | −29.7% | 165 | −87.9% | 20,958.7 | −83.7% | |

| −25.0% | 61.04 | −19.9% | 405 | −70.5% | 46,544.49 | −63.9% | |

| −12.5% | 66.56 | −12.6% | 780 | −43.1% | 83,072.18 | −35.5% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 83.75 | 10.0% | 2149 | 57.0% | 180,432.5 | 40.1% | |

| +25.0% | 91.79 | 20.5% | 3166 | 131.2% | 233,067.2 | 80.9% | |

| +37.5% | 100.49 | 31.9% | 4444 | 224.5% | 280,987.5 | 118.1% | |

| +50.0% | 112.6 | 47.8% | 6012 | 339.0% | 315,223.1 | 144.7% | |

| −50.0% | 69.66 | −8.5% | 1258 | −8.1% | 89,876.99 | −30.2% | |

| −37.5% | 71.75 | −5.8% | 1305 | −4.7% | 98,882.17 | −23.2% | |

| −25.0% | 73.51 | −3.5% | 1337 | −2.4% | 108,464.5 | −15.8% | |

| −12.5% | 74.94 | −1.6% | 1357 | −0.9% | 118,480 | −8.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 77.04 | 1.2% | 1376 | 0.5% | 139,370.8 | 8.2% | |

| +25.0% | 77.81 | 2.2% | 1380 | 0.8% | 150,098.5 | 16.5% | |

| +37.5% | 78.47 | 3.0% | 1383 | 1.0% | 160,951.2 | 25.0% | |

| +50.0% | 79.02 | 3.8% | 1384 | 1.1% | 171,898.6 | 33.5% | |

| −50.0% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 131,375.4 | 2.0% | |

| −37.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 130,734.2 | 1.5% | |

| −25.0% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 130,092.9 | 1.0% | |

| −12.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 129,451.7 | 0.5% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,170 | −0.5% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,529.2 | −1.0% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,888.4 | −1.5% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,247.7 | −2.0% | |

| −50.0% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 1366 | −0.2% | 137,397.7 | 6.7% | |

| −37.5% | 75.94 | −0.3% | 1367 | −0.1% | 135,249.8 | 5.0% | |

| −25.0% | 75.94 | −0.3% | 1367 | −0.1% | 133,102.4 | 3.3% | |

| −12.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 130,956.3 | 1.7% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,666.4 | −1.7% | |

| +25.0% | 76.27 | 0.1% | 1370 | 0.1% | 124,523.1 | −3.3% | |

| +37.5% | 76.38 | 0.3% | 1371 | 0.1% | 122,380.6 | −5.0% | |

| +50.0% | 76.38 | 0.3% | 1371 | 0.1% | 120,239.5 | −6.7% | |

| −50.0% | 76.38 | 0.3% | 1326 | −3.2% | 128,729.9 | −0.1% | |

| −37.5% | 76.27 | 0.1% | 1336 | −2.4% | 128,780 | 0.0% | |

| −25.0% | 76.27 | 0.1% | 1348 | −1.6% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1358 | −0.8% | 128,821.1 | 0.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1380 | 0.8% | 128,779.7 | 0.0% | |

| +25.0% | 75.94 | −0.3% | 1391 | 1.5% | 128,726.7 | −0.1% | |

| +37.5% | 75.94 | −0.3% | 1402 | 2.4% | 128,652.3 | −0.1% | |

| +50.0% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 1413 | 3.2% | 128,555.3 | −0.2% | |

| −50.0% | 75.72 | −0.6% | 1365 | −0.3% | 141,449.2 | 9.8% | |

| −37.5% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 1366 | −0.2% | 138,287.1 | 7.4% | |

| −25.0% | 75.94 | −0.3% | 1367 | −0.1% | 135,126.5 | 4.9% | |

| −12.5% | 76.05 | −0.1% | 1368 | −0.1% | 131,967.7 | 2.5% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.27 | 0.1% | 1370 | 0.1% | 125,656 | −2.4% | |

| +25.0% | 76.38 | 0.3% | 1371 | 0.1% | 122,503.5 | −4.9% | |

| +37.5% | 76.49 | 0.4% | 1372 | 0.2% | 119,353.4 | −7.3% | |

| +50.0% | 76.6 | 0.6% | 1373 | 0.3% | 116,206.4 | −9.8% | |

| −50.0% | 78.8 | 3.5% | 1384 | 1.0% | 191,934.5 | 49.0% | |

| −37.5% | 78.36 | 2.9% | 1382 | 1.0% | 175,998.9 | 36.6% | |

| −25.0% | 77.81 | 2.2% | 1380 | 0.8% | 160,141.1 | 24.3% | |

| −12.5% | 77.04 | 1.2% | 1376 | 0.5% | 144,394 | 12.1% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 74.83 | −1.7% | 1355 | −1.0% | 113,481.2 | −11.9% | |

| +25.0% | 73.07 | −4.1% | 1330 | −2.9% | 98,560.15 | −23.5% | |

| +37.5% | 70.065 | −8.0% | 1268 | −7.4% | 84,313.27 | −34.5% | |

| +50.0% | 67.46 | −11.4% | 1197 | −12.6% | 71,141.62 | −44.8% | |

| −50.0% | 66.91 | −12.1% | 1181 | −13.8% | 69,304.32 | −46.2% | |

| −37.5% | 70.21 | −7.8% | 1271 | −7.2% | 82,752.9 | −35.8% | |

| −25.0% | 72.74 | −4.5% | 1324 | −3.3% | 97,407.64 | −24.4% | |

| −12.5% | 74.72 | −1.9% | 1354 | −1.1% | 112,859 | −12.4% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 77.15 | 1.3% | 1377 | 0.5% | 145,078.5 | 12.6% | |

| +25.0% | 78.03 | 2.5% | 1381 | 0.9% | 161,552.1 | 25.4% | |

| +37.5% | 78.58 | 3.2% | 1383 | 1.0% | 178,165 | 38.3% | |

| +50.0% | 79.13 | 3.9% | 1384 | 1.1% | 194,876.5 | 51.3% | |

| −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,156.8 | 0.3% | |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,070.3 | 0.2% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,983.8 | 0.1% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,897.3 | 0.1% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,724.3 | −0.1% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,637.8 | −0.1% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,551.3 | −0.2% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,465 | −0.3% | |

| −50.0% | 63.71 | −16.3% | 2563 | 92.9% | 391,410.6 | 203.9% | |

| −37.5% | 67.02 | −12.0% | 2203 | 65.8% | 308,076.2 | 139.2% | |

| −25.0% | 70.1 | −8.0% | 1875 | 41.2% | 235,946.9 | 83.2% | |

| −12.5% | 73.18 | −3.9% | 1585 | 19.3% | 176,456 | 37.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1328 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 79.02 | 3.8% | 1103 | −16.9% | 91,519.04 | −29.0% | |

| +25.0% | 81.33 | 6.8% | 906 | −31.8% | 62,920.9 | −51.2% | |

| +37.5% | 85.73 | 12.6% | 740 | −44.3% | 41,514.3 | −67.8% | |

| +50.0% | 89.6 | 17.6% | 592 | −55.4% | 25,845.7 | −79.9% | |

| −50.0% | 74.94 | −1.6% | 1357 | −0.9% | 185,842.4 | 44.3% | |

| −37.5% | 75.17 | −1.3% | 1359 | −0.7% | 171,553.5 | 33.2% | |

| −25.0% | 75.39 | −1.0% | 1362 | −0.6% | 157,281.4 | 22.1% | |

| −12.5% | 75.72 | −0.6% | 1365 | −0.3% | 143,031 | 11.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.6 | 0.6% | 1373 | 0.3% | 114,633.8 | −11.0% | |

| +25.0% | 77.37 | 1.6% | 1378 | 0.6% | 100,520.5 | −22.0% | |

| +37.5% | 78.25 | 2.7% | 1382 | 0.9% | 86,507.08 | −32.8% | |

| +50.0% | 79.57 | 4.5% | 1384 | 1.1% | 72,658.39 | −43.6% | |

| h | −50.0% | 74.83 | −1.7% | 1355 | −1.0% | 114,611 | −11.0% |

| −37.5% | 75.17 | −1.3% | 1359 | −0.7% | 118,131.7 | −8.3% | |

| −25.0% | 75.5 | −0.9% | 1363 | −0.5% | 121,673.3 | −5.5% | |

| −12.5% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 1366 | −0.2% | 125,233.7 | −2.8% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.38 | 0.3% | 1371 | 0.1% | 132,403.5 | 2.8% | |

| +25.0% | 76.6 | 0.6% | 1373 | 0.3% | 136,009.8 | 5.6% | |

| +37.5% | 76.82 | 0.9% | 1375 | 0.4% | 139,628.7 | 8.4% | |

| +50.0% | 77.04 | 1.2% | 1376 | 0.5% | 143,259.2 | 11.2% | |

| −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,887.7 | 0.1% | |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,868.4 | 0.0% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,849.2 | 0.0% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,830 | 0.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,791.5 | 0.0% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,772.3 | 0.0% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,753.1 | 0.0% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,733.9 | −0.1% | |

| −50.0% | 75.28 | −1.2% | 1361 | −0.6% | 175,006.4 | 35.9% | |

| −37.5% | 75.5 | −0.9% | 1363 | −0.5% | 163,443.6 | 26.9% | |

| −25.0% | 75.61 | −0.7% | 1364 | −0.4% | 151,888.5 | 17.9% | |

| −12.5% | 75.83 | −0.4% | 1366 | −0.2% | 140,343 | 9.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.49 | 0.4% | 1372 | 0.2% | 117,297.6 | −8.9% | |

| +25.0% | 76.93 | 1.0% | 1376 | 0.4% | 105,812.2 | −17.9% | |

| +37.5% | 77.48 | 1.7% | 1379 | 0.7% | 94,369.97 | −26.7% | |

| +50.0% | 78.36 | 2.9% | 1382 | 1.0% | 82,999.77 | −35.6% | |

| x | −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 111,825 | −13.2% |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 118,619.3 | −7.9% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 123,148.9 | −4.4% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,384.2 | −1.9% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 130,698.1 | 1.5% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 132,207.9 | 2.6% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 133,443.2 | 3.6% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 134,472.7 | 4.4% | |

| −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 131,127 | 1.8% | |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 130,547.9 | 1.3% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,968.9 | 0.9% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,389.8 | 0.4% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,231.7 | −0.4% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,652.6 | −0.9% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,073.6 | −1.3% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 126,494.5 | −1.8% | |

| −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,325 | 0.4% | |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,196.8 | 0.3% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 129,068.2 | 0.2% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,939.4 | 0.1% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,682.1 | −0.1% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,553.4 | −0.2% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,424.7 | −0.3% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,296 | −0.4% | |

| k | −50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,814 | 0.0% |

| −37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,813.2 | 0.0% | |

| −25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,812.4 | 0.0% | |

| −12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,811.6 | 0.0% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,809.9 | 0.0% | |

| +25.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,809.1 | 0.0% | |

| +37.5% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,808.3 | 0.0% | |

| +50.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,807.5 | 0.0% | |

| −50.0% | 69.99 | −8.1% | 1266 | −7.6% | 139,484.4 | 8.3% | |

| −37.5% | 71.31 | −6.4% | 1296 | −5.4% | 136,051 | 5.6% | |

| −25.0% | 72.74 | −4.5% | 1324 | −3.3% | 133,080.7 | 3.3% | |

| −12.5% | 74.39 | −2.3% | 1350 | −1.4% | 130,645.8 | 1.4% | |

| 0.0% | 76.16 | 0.0% | 1369 | 0.0% | 128,810.8 | 0.0% | |

| +12.5% | 77.92 | 2.3% | 1381 | 0.8% | 127,613.1 | −0.9% | |

| +25.0% | 79.57 | 4.5% | 1384 | 1.1% | 127,051.9 | −1.4% | |

| +37.5% | 81.22 | 6.6% | 1380 | 0.8% | 127,090.8 | −1.3% | |

| +50.0% | 82.76 | 8.7% | 1369 | 0.0% | 127,666.6 | −0.9% | |

References

- Mokhtari, H. Economic order quantity for joint complementary and substitutable items. Math. Comput. Simul. 2018, 154, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.W. How many parts to make at once. Mag. Manag. 1913, 10, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M.; Adetunji, O. Economic order quantity model for growing items with imperfect quality. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2019, 6, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Yadav, S. Price and profit structuring for single manufacturer multi-buyer integrated inventory supply chain under price-sensitive demand condition. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Halim, M.A.; AlArjani, A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Uddin, M.S. Inventory management with hybrid cash-advance payment for time-dependent demand, time-varying holding cost and non-instantaneous deterioration under backordering and non-terminating situations. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 8469–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, M.A.N.; Soni, H.N. Joint pricing and inventory decisions for perishable products with age-, stock-, and price-dependent demand rate. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2020, 71, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M. Three-echelon circular economic production–inventory model for deteriorating items with imperfect quality and carbon emissions considerations under various emissions policies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.L. An inventory model for deteriorating items with stock-dependent consumption rate and shortages under inflation and time discounting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 168, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, M.K.; Jaber, M.Y. Economic production quantity model for items with imperfect quality. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2000, 64, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C. An application of fuzzy sets theory to the EOQ model with imperfect quality items. Comput. Oper. Res. 2004, 31, 2079–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, H.M.; Yu, J.; Chen, M.C. Optimal inventory model for items with imperfect quality and shortage backordering. Omega 2007, 35, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantaras, I.; Skouri, K.; Jaber, M.Y. Inventory models for imperfect quality items with shortages and learning in inspection. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 5334–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E. A complement to “A comprehensive note on: An economic order quantity with imperfect quality and quantity discounts”. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 6338–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.T.; Hsu, L.F. An EOQ model with imperfect quality items, inspection errors, shortage backordering, and sales returns. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Zhong, Y. A synergic economic order quantity model with trade credit, shortages, imperfect quality and inspection errors. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleizadeh, A.A.; Khanbaglo, M.P.S.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E. An EOQ inventory model with partial backordering and reparation of imperfect products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggi, C.K.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; Tiwari, S.; Shafi, A. Two-warehouse inventory model for deteriorating items with imperfect quality under the conditions of permissible delay in payments. Sci. Iran. 2017, 24, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Economic order quantity for growing items. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 155, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekitabar, M.; Yaghoubi, S.; Gholamian, M.R. A novel mathematical inventory model for growing-mortal items (case study: Rainbow trout). Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 71, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilpourazari, S.; Pasandideh, S.H.R.; Niaki, S.T.A. Optimizing a multi-item economic order quantity problem with imperfect items, inspection errors, and backorders. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 11671–11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M.; Adetunji, O. Optimal inventory replenishment and shipment policies in a four-echelon supply chain for growing items with imperfect quality. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2020, 8, 130–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmohammad-Zia, N.; Karimi, B. Optimal replenishment and breeding policies for growing items. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 7005–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M.; Adetunji, O. Optimal lot-sizing and shipment decisions in a three-echelon supply chain for growing items with inventory level-and expiration date-dependent demand. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 90, 1204–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Duari, N.K.; Chakrabarti, T. Inventory Model for Growing Items and Its Waste Management. In Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence for Inventory and Supply Chain Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari, H.; Salmasnia, A.; Fallahi, A. Economic production quantity under possible substitution: A scenario analysis approach. Int. J. Ind. Eng. 2022, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nobil, A.H.; Sedigh, A.H.A.; Cardenas-Barron, L.E. A generalized economic order quantity inventory model with shortage: Case study of a poultry farmer. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 44, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; Nobil, A.H. Sustainable inventory models for a three-echelon food supply chain with growing items and price-and carbon emissions-dependent demand under different emissions regulations. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2024, 13, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghare, P.M. A model for an exponentially decaying inventory. J. Ind. Eng. 1963, 14, 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.T. Inventory models with stock-dependent demand and nonlinear holding costs for deteriorating items. Asia-Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 21, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Ghosh, S.K.; Chaudhuri, K.S. An EOQ model for a deteriorating item with time dependent quadratic demand under permissible delay in payment. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyadana, G.A.; Wee, H.M. An economic production quantity model for deteriorating items with preventive maintenance policy and random machine breakdown. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2012, 43, 1870–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangam, A. Optimal price discounting and lot-sizing policies for perishable items in a supply chain under advance payment scheme and two-echelon trade credits. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 139, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, S.S.; Chukwu, W.I.E. An Economic order quantity model for Items with Three-parameter Weibull distribution Deterioration, Ramp-type Demand and Shortages. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 9698–9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleizadeh, A.A. An economic order quantity model for deteriorating item in a purchasing system with multiple prepayments. Appl. Math. Model. 2014, 38, 5357–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viji, G.; Karthikeyan, K. An economic production quantity model for three levels of production with Weibull distribution deterioration and shortage. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Duary, A.; Khan, M.; Shaikh, A.A.; Bhunia, A.K. Interval valued demand related inventory model under all units discount facility and deterioration via parametric approach. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 2455–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.K.; Patra, K.; Mondal, S.K. A new economic order quantity model for deteriorated items under the joint effects of stock dependent demand and inflation. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiu, S.; Ali, M.K.M. An enhanced EPQ model: Incorporating Weibull distribution deterioration, defective items, and dynamic demands for sustainable production optimization. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunadevi, E.; Umamaheswari, S. Enhancing ameliorating items with sustainable inventory management strategies: A Weibull approach for time and price-dependent demand trends. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.R.; Mukherjee, S.; Balan, C.V. An order-level lot size inventory model with inventory-level dependent demand and deterioration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1997, 48, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Kendall, G. A model for fresh produce shelf-space allocation and inventory management with freshness-condition-dependent demand. INFORMS J. Comput. 2008, 20, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chang, C.T.; Cheng, M.C.; Teng, J.T.; Al-Khateeb, F.B. Inventory management for fresh produce when the time-varying demand depends on product freshness, stock level and expiration date. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2016, 3, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.C.; Min, J.; Teng, J.T.; Li, F. Inventory and shelf-space optimization for fresh produce with expiration date under freshness-and-stock-dependent demand rate. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2016, 67, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L.; Sauer, J.; Claus, T.; Nehls, U. Development and simulation analysis of a new perishable inventory model with a closing days constraint under non-stationary stochastic demand. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 118, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Panda, G.C.; Konstantaras, I.; Taleizadeh, A.A. Inventory system with expiration date: Pricing and replenishment decisions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 132, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M.; Adetunji, O. A three-echelon supply chain for economic growing quantity model with price-and freshness-dependent demand: Pricing, ordering and shipment decisions. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Khan, A.R.; Alrasheedi, A.F. Advertising and pricing strategies of an inventory model with product freshness-related demand and expiration date-related deterioration. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 73, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Cruz-Márquez, C.G.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; Mandal, B. An inventory model for growing items with imperfect quality when the demand is price sensitive under carbon emissions and shortages. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6649048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, G.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Wang, S. Managing carbon footprints in inventory management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 132, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchery, Y.; Ghaffari, A.; Jemai, Z.; Dallery, Y. Including sustainability criteria into inventory models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 222, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Ballot, E.; Fontane, F. The reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from freight transport by pooling supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, S.; Mazzoldi, L.; Jaber, M.Y. Vendor-managed inventory with consignment stock agreement for single vendor–single buyer under the emission-trading scheme. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Bian, Y. Production lot-sizing and carbon emissions under cap-and-trade and carbon tax regulations. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Daryanto, Y.; Wee, H.M. Sustainable inventory management with deteriorating and imperfect quality items considering carbon emission. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hai, J. Inventory management for one warehouse multi-retailer systems with carbon emission costs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 130, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Santana, A.A.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E. A sustainable inventory model considering a discontinuous transportation cost function and different sources of pollution. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.03781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, N.M.; Kelle, P. Using social work donation as a tool of corporate social responsibility in a closed-loop supply chain considering carbon emissions tax and demand uncertainty. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2021, 72, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Tian, X.; Feng, C. Inventory management research for growing items with carbon-constrained. In Proceedings of the 2016 35th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chengdu, China, 27–29 July 2016; pp. 9588–9593. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, V.; Shekhar, C.; Saurav, A.; Kumar, A. Sustainable inventory management with trapezoidal demand and amelioration under carbon regulations. Inf. Sci. 2025, 730, 122883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurav, A.; Yadav, V.; Shekhar, C. An inventory optimization model for reliable and sustainable supply chains under trade credit and carbon constraints. Supply Chain Anal. 2025, 11, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatjane, M. Sustainable inventory, pricing, and marketing strategies for imperfect quality perishable items with inspection errors and advertisement-, expiration date-and price-dependent demand under carbon emissions policies. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2024, 5, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, P.D.; DeMarais, R.A. Psychic stock: An independent variable category of inventory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1990, 20, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.C.; Urban, T.L. A deterministic inventory system with an inventory-level-dependent demand rate. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1988, 39, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfares, H.K. Inventory model with stock-level dependent demand rate and variable holding cost. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2007, 108, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.K.; Chang, C.T. Optimal ordering and transfer policy for an inventory with stock dependent demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B. An EOQ model with delay in payments and stock dependent demand in the presence of imperfect production. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 8295–8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Jana, D.K.; Roy, T.K. Multi-item integrated supply chain model for deteriorating items with stock dependent demand under fuzzy random and bifuzzy environments. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 88, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pando, V.; San-José, L.A.; García-Laguna, J.; Sicilia, J. Optimal lot-size policy for deteriorating items with stock-dependent demand considering profit maximization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 117, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Keblis, M.F.; Li, G. Optimal pricing and replenishment policy for deteriorating inventory under stock-level-dependent, time-varying and price-dependent demand. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Characteristics of the Inventory System | Solution Technique | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Items | Growing Items | Imperfect Quality | Carbon Tax | Shortage | Constant Demand | Dependent Demand | Deterioration | Freshness | Closed Form | Heuristic | |

| Harris [2] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Salameh and Jaber [9] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rezaei [18] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zhang et al. [58] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Nobil et al. [26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sebatjane and Adetunji [3] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Pourmohammad-Zia and Karimi [22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sebatjane and Adetunji [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| De-la-Cruz-Márquez et al. [48] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Mokhtari et al. [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Khan et al. [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Yadav et al. [59] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sebatjane [61] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sebatjane et al. [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Saurav et al. [60] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| This paper | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| a | : Scaling parameter for the demand function (in units of weight/time). |

| b | : The shape parameter representing the elasticity of demand. |

| : Deterioration cost (in Rand/weight/time). | |

| : Purchasing cost per unit (weight/time). | |

| : Screening cost per unit item screened (in Rand/weight). | |

| D | : Demand rate (weight/time). |

| : Product’s freshness index of the inventory at time t, which is a function of the expiration date (dimensionless quantity). | |

| : Feeding function for each item. | |

| : Feeding cost (in Rand/weight unit/time). | |

| h | : Holding cost rate for perfect products (in Rand/weight/time). |

| : The instantaneous state of inventory level at time t. | |

| K | : Ordering cost (in Rand/cycle). |

| L | : The expiration date (or shelf life) of the product (in units of time). |

| : Percentage rate of imperfect items in Q. | |

| : Selling price per unit of each imperfect product (in Rand/weight). | |

| : Selling price per unit of each perfect product (Rand/weight). | |

| : Deterioration function. | |

| : Rate of deterioration. | |

| : Growth rate (in units of weight/item/time). | |

| : Holding cost rate for imperfect product (in Rand/weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions caused by holding items of imperfect quality in the warehouse (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions caused by deteriorated items in the warehouse (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions made during the purchasing activity (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions created during the inspection process (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions generated during the feeding period (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Amount of carbon emissions caused by holding items of the perfect quality in the warehouse (in units of /weight/time). | |

| : Approximated weight of each newborn item (in weight/item). | |

| : Approximated weight of each grown item at the time of slaughtering (in weight/item). | |

| x | : Screening rate (in weight/time). |

| : Carbon tax rate (in Rand/unit of ). | |

| : Deterioration cost (in Rand/time). | |

| : Feeding cost (in Rand/time). | |

| : Holding cost of the good products (in Rand/time). | |

| : Holding cost of the imperfect products (in Rand/time). | |

| : Total cost function (in Rand). | |

| : Total profit function. | |

| : Total profit (in Rand/time). | |

| : Total revenue function. | |

| : Purchasing cost of the products (in Rand/weight). | |

| : Screening cost (in Rand/weight). | |

| : Total carbon tax cost (in Rand/time). | |

| : Total carbon emissions made by deteriorating products (in units of ). | |

| : Total carbon emissions generated during the feeding process (in units of ). | |

| : Total carbon emissions generated during inventory holding (in units of ). | |

| : Total carbon emissions caused by the purchasing action (in units of ). | |

| : Total carbon emissions made by the screening process (in units of ). |

| Symbol | Description of the Decision Variables |

|---|---|

| Q | : Order size/total weight of the inventory per cycle (in weight). |

| : Duration of growing period (in time). | |

| : Duration of the screening time (in time). | |

| T | : Cycle time. |

| y | : Number of ordered newborn items per cycle (in units of items). |

| Symbol | Value | Symbol | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | : | 40 g/day | : | 0.05 Rand/g/day | |

| L | : | 130 Days | : | 0.5 g of /g/day | |

| b | : | 0.63 | : | 0.05 | |

| h | : | 0.1 Rand/g/day | : | 15.00 Rand/g | |

| : | 1 g of /g/day | : | 7.00 Rand/g | ||

| : | 0.01 Rand/g/day | : | 0.1 g of /g/day | ||

| : | 0.15 | K | : | 500 Rand | |

| : | 0.05 Rand/g | : | 0.5 g of /g/day | ||

| : | 4.00 Rand/g | : | 40.00 g of /g/day | ||

| : | 53 g/chick | : | 1267 g/chick | ||

| : | 0.08 Rand/g/day | : | 0.8 g of /g/day | ||

| x | : | 144,000 g/day | : | 42 g/chick/day | |

| : | 0.45 Rand/g of |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tshinangi, K.; Adetunji, O.; Yadavalli, S. An Inventory Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality, Deterioration, and Freshness- and Inventory Level-Dependent Demand Under Carbon Emissions. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040181

Tshinangi K, Adetunji O, Yadavalli S. An Inventory Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality, Deterioration, and Freshness- and Inventory Level-Dependent Demand Under Carbon Emissions. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(4):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040181

Chicago/Turabian StyleTshinangi, Kapya, Olufemi Adetunji, and Sarma Yadavalli. 2025. "An Inventory Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality, Deterioration, and Freshness- and Inventory Level-Dependent Demand Under Carbon Emissions" AppliedMath 5, no. 4: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040181

APA StyleTshinangi, K., Adetunji, O., & Yadavalli, S. (2025). An Inventory Model for Growing Items with Imperfect Quality, Deterioration, and Freshness- and Inventory Level-Dependent Demand Under Carbon Emissions. AppliedMath, 5(4), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040181