Abstract

To develop a modifier based on diethanolamine, a corresponding phosphoramidite for automated solid-phase deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis was synthesized. The influence of this modifier on the thermal stability of the terminally modified nucleic acids showed a dependence on the neighboring nucleobases and could be attributed to the fraying of the DNA ends. The potential for modification with dioxazaborocanes was first investigated using a small molecule model, and the formation of the dioxazaborocane was confirmed both in solution and in the solid state. Such a modification could expand the scope of xenonucleic acids in the future and modulate the properties of nucleic acids in solution. The influence on the thermal stability of the modified nucleic acids was minimal. In the future, this modification will be extended to internal incorporation and the potential of dioxazaborocanes in the nucleic acid context will be further exploited.

1. Introduction

The investigation of the behavior of DNA in solvent mixtures is particularly important when studying the interaction of DNA with small organic molecules, as these are not always completely soluble in water. However, not all solvent mixtures preserve native DNA structure across all compositions. For example, alcohols interfere with the ability of DNA to form stabilizing hydrogen bonds, which leads to a decrease in melting temperature when methanol and ethanol are added [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Higher ethanol concentrations even lead to the formation of aggregates [7,8,9] or induce B-A transitions [10,11]. The aggregation from alcoholic solution can also be used technically for the precipitation of nucleic acids and their purification [12,13]. In addition, other polyols also show thermal destabilization, although the extent of this depends heavily on the alcohol being investigated [14,15]. Other solvents, such as DMSO, also interact strongly with nucleic acids and lead to significant thermal destabilization even in small quantities [1,5,16,17,18]. The interaction of polyols and general compatibility with nucleic acids also opens up new areas of application, such as the controlled release of plasmid DNA from corresponding hydrogels [19]. In general, interaction with polyols allows nucleic acids to be stabilized in biological systems, for example, against degradation by enzymes, and be transported [20,21,22]. This study aims to investigate the influence of covalently bound alcohols on the stability of DNA duplexes and to gather initial findings on the modification of nucleic acids with dioxazaborocanes. Such modification can expand the range of available tools for adjusting the properties of nucleic acids.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

All chemicals used in this study were of p.a. grade and were obtained from ABCR (Karlsruhe, Germany), Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), Alfa Aesar (Karlsruhe, Germany), AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany), BLDpharm (Shanghai, China), Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), Fisher Scientific, Fluorochem (Hadfield, UK), Glen Research (Sterling, VA, USA), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), TCI (Tokyo, Japan) or VWR (Radnor, PA, USA) and used, if not stated otherwise, without further purification. The dry solvents used were dried according to standard procedures and stored under argon over molecular sieves.

NMR spectra were recorded on an Avance Neo 400 (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported as δ, parts per million (ppm), and referenced to internal solvent residues. Coupling constants J are stated in Hertz (Hz). The following abbreviations were used for spin multiplicities: d (doublet), t (triplet), br (broad signal), s (singlet), m (multiplet). The signals have been assigned based on corresponding 2D NMR spectra. The annotation is based on the connectivity of the atoms of the respective signals and these atoms are italicized in the annotation. High-resolution ESI-MS were recorded on an Impact II QTOF ESI-MS (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Elemental analysis was performed using a Vario EL III CHNS Analyzer (Langenselbold, Germany).

Compounds 1 and 5 were prepared according to the synthesis methods described in the literature [23].

2.2. Synthesis of DMT-Protected Triethanolamine

Triethanolamine (0.44 mL, 3.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMTr-Cl (2.25 g, 6.63 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) and dry DIPEA (1.13 mL, 6.65 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were dissolved in dry DCM (15 mL) and the reaction solution was stirred for four hours at room temperature. After filtration of the suspension, the solvent was removed from the filtrate under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, gradient: petroleum ether:ethyl acetate, 4:1 with triethylamine (3%) to ethyl acetate:methanol, 100:4 with triethylamine (3%)). The isolated compounds were dried under vacuum.

Triple-protected: Yield: 0.28 g (0.28 mmol, 8%), yellow, viscous liquid. Rf: 0.22 (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate, 4:1 with triethylamine (3%)). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 7.41–7.36 (m, 6H, CCCHPh), 7.28–7.23 (m, 12H, CCCHOMe), 7.21–7.16 (m, 9H, CCHCHPh, CHCHCHPh), 6.77–6.71 (m, 12H, CCHCHOMe), 3.74 (s, 18H, OCH3), 3.05 (t, 3JHH = 6.2 Hz, 6H, OCH2), 2.73 (t, 3JHH = 6.2 Hz, 6H, NCH2). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 159.0 (COCH3), 146.1 (CCCHPh), 137.1 (CCCHOMe), 130.5 (CCCHOMe), 128.7 (CCCHPh), 128.3 (CHCHCH), 127.1 (CHCHCH), 113.5 (CHCOCH3), 86.5 (OCC), 63.5 (CH2CH2O), 56.3 (NCH2CH2), 55.7 (OCH3). 15N{1H} NMR (41 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 31. ESI-MS (m/z) [C69H69NO9+H]+: calcd.: 1056.5045, found: 1056.5042. Elemental analysis (%): C69H69NO9: calcd. C 78.5, H 6.6, N 1.3; found C 78.2, H 6.7, N 1.3.

Double-protected 2: Yield: 1.22 g (1.61 mmol, 49%), yellowish, solid. Rf: 0.10 (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate, 4:1 with triethylamine (3%)). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 7.42–7.38 (m, 4H, CCCHPh), 7.30–7.27 (m, 8H, CCCHOMe), 7.26–7.22 (m, 4H, CCHCHPh), 7.22–7.17 (m, 2H, CHCHCHPh), 6.81–6.76 (m, 8H, CCHCHOMe), 3.76 (s, 12H, OCH3), 3.44 (t, 3JHH = 5.3 Hz, 2H, CH2OH), 3.12 (t, 3JHH = 5.9 Hz, 4H, CH2OC), 2.72 (t, 3JHH = 5.9 Hz, 4H, CH2CH2OC), 2.62 (t, 3JHH = 5.3 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2OH). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 159.1 (COCH3), 145.9 (CCCHPh), 137.0 (CCCHOMe), 130.5 (CCCHOMe), 128.7 (CCCHPh), 128.3 (CHCHCH), 127.2 (CHCHCH), 113.6 (CHCOCH3), 86.7 (OCC), 62.7 (CH2OC), 59.4 (CH2OH), 57.4 (CH2CH2OC), 55.8 (OCH3), 54.8 (CH2CH2OC). 15N{1H} NMR (41 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 25. ESI-MS (m/z) [C48H51NO7+H]+: calcd.: 754.3738, found: 754.3744. Elemental analysis (%): C48H51NO7: calcd. C 76.5, H 6.8, N 1.9; found C 76.4, H 6.8, N 1.8.

Single-protected: Yield: 0.44 g (0.98 mmol, 30%), yellowish, solid. Rf: 0.14 (ethyl acetate:methanol, 100:4 with triethylamine (3%)). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 7.47–7.43 (m, 2H, CCCHPh), 7.36–7.31 (m, 4H, CCCHOMe), 7.31–7.28 (m, 2H, CCHCHPh), 7.26–7.20 (m, 1H, CHCHCHPh), 6.90–6.83 (m, 4H, CCHCHOMe), 3.79 (s, 6H, OCH3), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 5.4 Hz, 4H, CH2OH), 3.19 (t, 3JHH = 5.6 Hz, 2H, CH2OC), 2.76 (t, 3JHH = 5.6 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2OC), 2.66 (t, 3JHH = 5.4 Hz, 4H, CH2CH2OH). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 159.2 (COCH3), 145.8 (CCCHPh), 136.8 (CCCHOMe), 130.5 (CCCHOMe), 128.7 (CCCHPh), 128.4 (CHCHCH), 127.3 (CHCHCH), 113.6 (CHCOCH3), 87.1 (OCC), 62.5 (CH2OC), 60.2 (CH2OH), 57.2 (CH2CH2OC), 55.8 (OCH3), 54.9 (CH2CH2OC). 15N{1H} NMR (41 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 23. ESI-MS (m/z) [C27H33NO5+H]+: calcd.: 452.2431, found: 452.2438.

2.3. Synthesis of the Trityl-Protected Phosphoramidite 3

The double-protected compound 1 (0.16 g, 0.25 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and triethylamine (0.03 mL, 0.3 mmol, 1.2 equiv.). CEDIP-Cl (0.07 mL, 0.3 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was added to the solution at room temperature, and the reaction solution was stirred for two hours at room temperature. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dried in a vacuum. Due to the instability of the compound, it was used directly in automated solid-phase synthesis. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 7.45–7.40 (m, 12H, CCCHPh), 7.30–7.20 (m, 18H, CHCHCH, CHCHCH), 3.76–3.66 (m, 2H, POCH2CH2C), 3.70–3.54 (m, 2H, POCH2CH2N), 3.62–3.53 (m, 2H, NCHCH3), 3.08 (t, 3JHH = 6.2 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2OC), 2.77 (t, 3JHH = 6.2 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2OC), 2.76 (t, 3JHH = 5.3 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2OP), 2.53–2.48 (m, 2H, POCH2CH2C), 1.16 (d, 3JHH = 6.6 Hz, 6H, CH3CHN), 1.12 (d, 3JHH = 6.6 Hz, 6H, CH3CHN). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 144.9 (CCCHPh), 129.1 (CCCHPh), 128.3 (CHCHCH), 127.2 (CHCHCH), 118.4 (NCCH2), 87.1 (OCC), 63.5 (CH2OC), 62.6 (d, 2JCP = 16.3 Hz, POCH2CH2N), 58.9 (d, 2JCP = 18.6 Hz, POCH2CH2C), 56.9 (d, 3JCP = 7.5 Hz, POCH2CH2N), 55.8 (CH2CH2OC), 43.4 (d, 2JCP = 12.4 Hz, PNCH), 24.9 (d, 3JCP = 7 Hz, NCHCH3), 20.8 (d, 3JCP = 6.6 Hz, POCH2CH2C). 15N{1H} NMR (51 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 250 (s, NCCH2), 99 (d, 1JNP = 85 Hz, CHNP), 30 (s, CH2NCH2). 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 147.7 (s). ESI-MS (m/z) [C53H60N3O4P+H]+: calcd.: 834.4394, found: 834.4384.

2.4. Synthesis of the DMT-Protected Phosphoramidite 4

The double-protected compound 2 (0.20 g, 0.27 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and DIPEA (0.05 mL, 0.3 mmol, 1.1 equiv.). CEDIP-Cl (0.07 mL, 0.3 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) was added to the solution at room temperature, and the reaction solution was stirred for two hours at room temperature. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dried in a vacuum. Due to the instability of the compound, it was used directly in automated solid-phase synthesis. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 7.45–7.40 (m, 4H, CCCHPh), 7.32–7.28 (m, 8H, CCCHOMe), 7.27–7.22 (m, 4H, CCHCHPh), 7.21–7.16 (m, 2H, CHCHCHPh), 6.82–6.76 (m, 8H, CCHCHOMe), 3.74 (s, 12H, OCH3), 3.71–3.66 (m, 2H, CCH2CH2), 3.57–3.53 (m, 2H, CH3CHN), 3.09 (t, 3JHH = 6.3 Hz, 4H, CH2OC), 2.77 (t, 3JHH = 6.3 Hz, 4H, CH2CH2OC), 2.53–2.48 (m, 2H, CCH2CH2), 1.17 (d, 3JHH = 6.8 Hz, 6H, CH3CHN), 1.12 (d, 3JHH = 6.8 Hz, 6H, CH3CHN). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 159.0 (COCH3), 146.0 (CCCHPh), 137.0 (CCCHOMe), 130.4 (CCCHOMe), 128.6 (CCCHPh), 128.2 (CHCHCH), 127.0 (CHCHCH), 118.4 (NCCH2), 113.4 (CHCOCH3), 86.4 (OCC), 63.3 (CH2OC), 62.6 (d, 2JCP = 16.3 Hz, POCH2CH2N), 58.8 (d, 2JCP = 18.5 Hz, POCH2CH2C), 56.9 (d, 3JCP = 7.5 Hz, POCH2CH2N), 55.8 (CH2CH2OC), 55.6 (OCH3), 43.5 (d, 2JCP = 12.4 Hz, PNCH), 24.9 (d, 3JCP = 7 Hz, NCHCH3), 20.8 (d, 3JCP = 6.7 Hz, POCH2CH2C). 15N{1H} NMR (51 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 249 (s, NCCH2), 98 (d, 1JNP = 85 Hz, CHNP), 30 (s, CH2NCH2). 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ (ppm) = 147.6 (s). ESI-MS (m/z) [C57H68N3O8P+H]+: calcd.: 954.4817, found: 954.4799.

2.5. Synthesis of Dioxazaborocane 6

Phenylboronic acid (0.03 g, 0.26 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in diethyl ether (5 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of compound 5 (0.10 g, 0.26 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in diethyl ether (10 mL), and the solution was stirred for 5 h at room temperature. The precipitate obtained was filtered, washed with diethyl ether and pentane, and dried under vacuum.

Yield: 0.11 g (0.24 mmol, 92%), white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ (ppm) = 8.02–7.98 (m, 2H, BCCHPh), 7.44–7.35 (m, 2H, CCHCHPh), 7.33–7.28 (m, 7H, CCCHTrt, CHCHCHPh), 7.10–7.00 (m, 9H, CHCHCHTrt, CHCHCHTrt), 3.87–3.80 (br, 4H, BOCH2), 2.81 (t, 3JHH = 5.1 Hz, 2H, CH2OC), 2.55–2.15 (br, 4H, BOCH2CH2), 2.30 (t, 3JHH = 5.1 Hz, 2H, NCH2). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, C6D6): δ (ppm) = 143.9 (CCCHTrt), 134.4 (BCCHPh), 128.9 (CCCHTrt), 128.2 (CHCHCHTrt), 127.9 (CHCHCHPh), 127.7 (CHCHCHPh), 127.5 (CHCHCHTrt), 87.9 (OCC), 63.8 (BOCH2), 60.2 (CH2CH2OC), 59.6 (CH2CH2OC), 58.1 (BOCH2CH2). 15N{1H} NMR (51 MHz, C6D6): δ (ppm) = 62 (s). 11B{1H} NMR (128 MHz, C6D6): δ (ppm) = 14.6 (s). ESI-MS (m/z) [C31H32BNO3+Na]+: calcd.: 499.2404, found: 499.2402. Elemental analysis (%): C31H32BNO3 · 0.5 H2O: calcd. C 76.6, H 6.8, N 2.9; found C 76.5, H 6.7, N 2.8.

2.6. UV/vis Spectroscopy and DNA Melting Point Determination

The UV/vis spectra were recorded on a Jasco (Tokyo, Japan) V-750 UV spectrometer using a quartz cuvette with a layer thickness of 1 cm. The temperature-dependent UV/vis absorption measurements were performed at 260 nm. The measurements were performed between 5 and 80 °C with a heating rate of 1 °C min–1 in 1 °C intervals. The sample solution contained 1.0 µM dsDNA (palindromic sequences), 150 mM sodium perchlorate, and 5 mM buffer. The following buffers with different pH values were used for this purpose: MES (pH 5.5), MOPS (pH 6.8), CHES (pH 9.0). To determine the melting temperature, the data were normalized according to Anorm = (A − Amin)/(Amax − Amin) with Anorm is the normalized absorption, Amax is the maximum absorption, and Amin is the minimum absorption. The melting temperature of the nucleic acids was determined based on explicit equations [24] for monophasic, bimolecular melting using van’t Hoff formalism, based on the sigmoidal curve profiles obtained from the temperature-dependent UV/vis spectra. The starting values for the iteration were chosen as the position of the inflection point for the melting temperature, the linear parts of the plateau at the respective ends of the sigmoidal curves for the slope and the intercept, and –300 kJ for the melting enthalpy.

2.7. CD Spectroscopy

The CD spectra of the oligonucleotides were recorded on a J-815 CD spectrometer (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) from Jasco in a quartz cuvette with a layer thickness of 1 cm. The measurements were performed at a temperature of 5 °C in a wavelength range from 200 to 400 nm with fivefold accumulation. The scan rate was 200 nm min−1 and the data interval was 0.1 nm. The sample solution contained 1.0 µM dsDNA (palindromic sequences), 150 mM sodium perchlorate, and 5 mM buffer. The following buffers with different pH values were used for this purpose: MES (pH 5.5), MOPS (pH 6.8), CHES (pH 9.0). The CD spectra were evaluated using the OriginPro 2024 10.1.0.170 program. All CD spectra underwent manual baseline adjustment using the last 50 measurement values.

2.8. DNA Synthesis

All aqueous solutions of salts and oligonucleotides were prepared using double-distilled water treated by Merck’s (Darmstadt, Germany) Milli-Q® Advantage A10 water purification system. The oligonucleotides were synthesized on a DNA/RNA synthesizer H-8 from K&A Laborgeräte (Schaafheim, Germany) in “DMT-On” mode in a batch size of 1 μmol each. The phosphoramidites of the nucleobases, guanine, adenine, thymine, and cytosine, as well as the other reagents for the synthesis cycle, were purchased from Glen Research, Sigma-Aldrich, VWR, and Alfa Aesar. After synthesis, the oligonucleotides were cleaved from the solid phase in a mixture of an aqueous ammonia solution (25%) and methylamine (1:1, 600 μL) at 60 °C for 15 min, whereby the protective groups were also cleaved from the nucleobases. Purification was then carried out using GlenPak™ DNA purification cartridges according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of the oligonucleotides was characterized using RP-HPLC (Jasco (multi-wavelength detector MD-2010 PLUS, HPLC pump PU-2080 PLUS, gradient unit LG-2080-02, Degasser DG-2080-53) with a 125/4 Nucleodur column (C18 HTec, particle size 5 μm, column dimensions 25 mm × 4 mm) from Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) with the following mobile phase mixtures: Buffer A (10 mM triethylammonium acetate in water, 5 mM EDTA) and buffer B (10 mM triethylammonium acetate in acetonitrile/water (80:20), 5 mM EDTA). Gradient: 100% A (0 min), 97% A (0–5 min), 60% A (5–45 min), 20% A (45–50 min). The identity of the purified oligonucleotides was determined by their mass. The mass spectrometric measurements (ESI(−)-MS) were performed using a Bruker Impact II mass spectrometer. To prepare the samples, 3 nmol of oligonucleotides were dissolved in 40 μL of double-distilled water and mixed with equal amounts of ammonium acetate (50 mM) in a water-acetonitrile mixture (9:1). The obtained data were deconvoluted to the neutral molecules using the algorithm “Maximum Entropy” [25].

2.9. DNA Concentration

The concentration of the oligonucleotides was determined using absorption at 260 nm on a NanoDrop2000c from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). According to Lambert-Beer’s law, the concentration can be determined from the absorption if the sequence is known: c = A260/(ε260 · d) with c is the concentration of the DNA, A260 is the absorption at 260 nm, ε260 is the molar extinction coefficient at 260 nm, and d is the layer thickness. The molar extinction coefficient of the oligonucleotides depends on the nucleobases they contain. For natural nucleobases, this is as follows at 260 nm: adenine (15.1 cm2 μmol−1), guanine (12.2 cm2 μmol−1), cytosine (7.1 cm2 μmol−1), and thymine (8.6 cm2 μmol−1) [26]. The extinction coefficient of DNA is calculated from the sum of the extinction coefficients of the nucleobases. In addition, this is multiplied by a correction factor f = 0.8 to take into account stacking interactions of the hybridized DNA: ε260 = f · ∑ εi · ni with ε260 is the molar extinction coefficient of the DNA at 260 nm, εi is the molar extinction coefficient at 260 nm of the individual nucleobases and ni is the number of nucleobases in the oligonucleotide.

2.10. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffractometry

X-ray diffraction analysis and data collection (Table S1) were performed using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å, graphite monochromator) on a Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) Venture D8 instrument equipped with a microsource and a Photon III CMOS detector and the software package APEX5 [27,28,29]. Initial structure solutions were obtained using the SHELXT [30] package via intrinsic phasing and refined with SHELXL [31] against all |F2| using initially isotropic and subsequently anisotropic thermal parameters. Anisotropic refinement was applied to all non-hydrogen atoms, while hydrogen atoms were positioned at ideal coordinates based on calculated positions and refined using the riding model. Hydrogen atoms bound to the oxygen atom of the co-crystallized water molecule were refined independently. Parts of the dioxazaborocane and the co-crystallized water are disordered over two positions (0.51:0.49). The graphical representations were prepared using the software Diamond 4.6.1 [32] and the table with the crystallographic data was prepared using the software WinGX [33].

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis

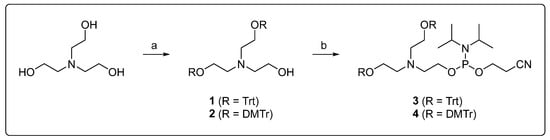

Triethanolamine was selected as the starting material for the incorporation of diethanolamine as a modifier into an oligonucleotide strand. For automated solid-phase synthesis, two hydroxyl groups were trityl-protected and the third converted to a phosphor-amidite (Scheme 1). The reaction conditions had previously been established with a trityl protecting group. The 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl derivatives were prepared through a reaction of triethanolamine with two equivalents of 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl chloride, in the presence of equimolar amounts of a base, under anhydrous conditions. In addition to the doubly protected derivative, which was the primary product under consideration, both the singly and triply protected derivatives were isolated and characterized. Subsequent functionalization of 1 and 2 was conducted using 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphor-amidite. Due to the low stability of the compounds, the reaction products were used in solid-phase DNA synthesis without further purification.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of solid-phase-synthesis-compatible diethanolamine building blocks: (a) Trt-Cl or DMTr-Cl (2.0 eq.), DIPEA (2.0 eq.), DCM, rt, 4 h, (b) CEDIP-Cl (1.2 eq. (Trt) or 1.1 eq. (DMTr)), NEt3 (1.2 eq. (Trt) or 1.1 eq. (DMTr)), DCM, rt, 2 h.

Due to the structural characteristics of the phosphoramidites 3 and 4, their incorporation into the oligonucleotide strand is constrained to the 5′ end. In order to assess the effect of the diol on the thermal stability of the duplexes, oligonucleotide strands were synthesized in which the nucleobase adjacent to the diethanolamine was permuted, and reference strands of the same length and reduced by one base pair were synthesized. To ensure efficient hybridization, the central part of all sequences was palindromic. When utilizing trityl-protected building blocks in the synthesis of oligonucleosides, the cleavage of the trityl protective groups following synthesis was found to be incomplete, even in the presence of substantial quantities of trifluoroacetic acid. Due to the risk of increased depurination reactions when using larger amounts of trifluoroacetic acid or longer incubation times, only 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl-protected building blocks were subsequently used for the synthesis of the oligonucleotides (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the oligonucleotides used in this study (N: diethanolamine modifier, □: no additional nucleotide compared to the sequence of canonical nucleobases of ODN1).

3.2. Spectroscopic Characterisation of Nucleic Acids

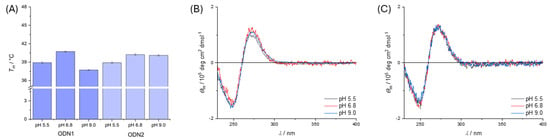

Temperature-dependent UV/vis spectra (Supplementary Materials Figure S12) show that the diethanolamine motif affects duplex stability in a pH-dependent manner. Initially, the thermal stability of the two duplexes ODN1 and ODN2 was investigated at three different pH values (Figure 1A). While the differences between the two duplexes at pH 5.5 and 6.8 are negligible, at pH 9.0 there were significantly different melting points for both duplexes (ΔTm = 2.7(3) °C). The cause of the pH dependence could be the changed degree of protonation of the amine of the attached diethanolamine. In principle, the hydroxyl groups of the diethanolamine can interact with the hydrogen bonds of the neighboring base pair, which can result in destabilization. The characteristic B-DNA structure of the duplexes is retained at all pH values (Figure 1B,C), as evidenced by the characteristic signals in the CD spectrum, so that the interactions of the hydroxyl groups have only a marginal influence on the overall structure of the duplex.

Figure 1.

(A) Bar chart of melting temperatures with standard deviation (3σ) for double-stranded oligonucleotides ODN1 and ODN2 in solution at different pH values. (B) CD spectra of ODN1 at different pH values and (C) CD spectra of ODN2 at different pH values. Measurement conditions: buffer (5 mM), NaClO4 (150 mM) and DNA (1.0 µM). Buffers used: MES at pH 5.5, MOPS at pH 6.8, CHES at pH 9.0.

To further investigate this destabilization, the nucleobase adjacent to the diethanol-amine was permuted. Since the influence of the diethanolamine on the melting point was greatest in the basic environment, further investigations were also carried out at pH 9.0 (Figure 2A). When adenine was incorporated adjacent to the diethanolamine instead of thymine, the incorporation of diethanolamine caused a similarly strong thermal destabilization of the duplex as previously observed (ODN3 to ODN4, ΔTm = 1.7(3) °C). The melting points of the duplexes with adjacent nucleobases C and G are practically unaffected by the neighboring diethanolamine. In the case of guanine, a slight stabilization of the double strand can even be observed (ODN5 to ODN6, ΔTm = 0.3(3) °C), while in the case of cytosine, both double strands have a similar melting temperature, which is slightly destabilized within the standard deviation (ODN7 to ODN8, ΔTm = 1.2(3) °C). The incorporation of diethanolamine into the duplexes generally has no effect on the overall structure of B-DNA, as the characteristic features of B-DNA are retained in the CD spectra (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Bar chart of melting temperatures with standard deviation (3σ) for double-stranded oligonucleotides ODN1 to ODN8 at pH 9.0. (B) CD spectra of ODN1 to ODN8 at pH 9.0. Measurement conditions: CHES (5 mM, pH 9.0), NaClO4 (150 mM) and DNA (1.0 µM).

With regard to the well-known phenomenon of fraying [34,35] at the ends of DNA duplexes, the following picture emerges: terminal A:T base pairs tend to fray more than analogous G:C base pairs, as has been proven theoretically and experimentally. The interaction of diethanolamine with the neighboring nucleobases can further enhance this effect and destabilize the double strand due to the broken hydrogen bonds of the terminal base pair. However, the nucleobases of the naturally more stable G:C base pair are not available for significant interactions with the neighboring diethanolamine, so that the incorporation of diethanolamine does not cause any change in the thermal stability of the double strand.

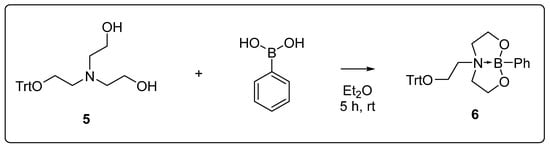

3.3. Synthesis and Characterisation of Dioxazaborocane-Based Modification

To further functionalize the diethanolamine moiety, a reaction with boronic acid was selected. In alkaline conditions, these react with diols to form corresponding boronates. At the beginning of the investigation, the general reactivity of the diethanolamine derivatives towards boronic acids was examined. For this purpose, the single-protected derivative 5, which was obtained as a byproduct in the reaction of triethanolamine with trityl chloride, was utilized because it contains the free diol unit, which is present in the oligonucleotide (Scheme 2). Additionally, the trityl group functions as a sterically demanding moiety, mimicking the steric demand of the nucleic acid. The conversion of 5 was carried out under similar conditions to the ones from the literature [36,37] for the formation of cyclic boronates. After the diethanolamine derivative 5 and phenylboronic acid were dissolved in diethyl ether, a white solid precipitated from the clear solution after a few hours, which was isolated by filtration. The dioxazaborocane 6 was obtained in a yield of 92%.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of the monotrityl-protected triethanolamine 5 with phenylboronic acid in diethyl ether.

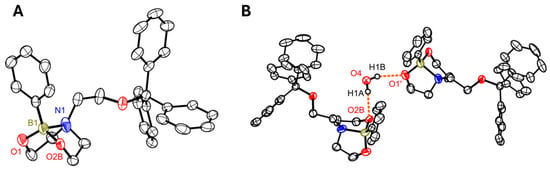

The NMR data show, based on the shift in the 11B NMR (δ = 14.6 ppm), that the dioxazaborocane has formed and that a stabilizing B–N bond is present. The signal broadening of the methylene groups in the 1H NMR also indicates a high degree of flexibility in the bicyclic structure, as has already been described for other dioxazaborocanes [38,39,40,41]. In addition, the compound could be crystallized from a concentrated solution in THF (Figure 3). This confirmed the presence of a B–N bond, but also showed that the methylene groups of the dioxazaborocane are disordered. This may be caused by the co-crystallized water molecule, which is capable of forming a hydrogen bond with each of the oxygen atoms of the dioxazaborocane (Hydrogen bond geometries (O4–H1A···O2B) d(D–H): 0.83(5) Å, d(H···A): 2.05(2) Å, <DHA: 167(4)°, d(D···A): 2.864(8) Å, A: O2B, b) (O4–H1A···O1′) d(D–H): 0.84(4) Å, d(H···A): 2.08(4) Å, <DHA: 163(4)°, d(D···A): 2.889(3) Å, A: O1′, symmetry code: (′) x + 1/2, y, −z + 3/2). The bond length between the nitrogen and the boron atom is 1.732(2) Å, which is significantly longer than in related [41] dioxazaborocanes, indicating a weakening of this stabilizing bond. This may be due to the increased steric demand of the trityl group, which prevents the substituents on the boron atom and the substituents on the nitrogen atom from coming closer together. The bond formed between the two atoms despite the steric demand prompted us to investigate its potential formation in DNA as well.

Figure 3.

(A) Molecular structure of compound 6 (co-crystallized water not shown for clarity). (B) Partial packing diagram highlighting the hydrogen bonding interactions mediated by the co-crystallized water molecule. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% level. H atoms have been omitted for clarity, except for H1A and H1B. The minor component (49%) of the disordered parts of the molecule is shown. Symmetry code: (′) x + 1/2, y, −z + 3/2; color code:  N,

N,

O,

O,

B,

B,

C.

C.

N,

N,

O,

O,

B,

B,

C.

C.

The potential and compatibility of boronates in nucleic acid chemistry has been impressively demonstrated in the recent past [42,43,44,45,46]. As backbone modification, boronates can be used to link oligonucleotides together in aqueous solution without impairing the function of formed aptamers, for example [47,48]. In addition, it has been shown that oligonucleotides modified in this way exhibit increased stability against phosphatases and nucleases [49,50]. Dioxazaborocanes [51] appear to be particularly attractive, as they exhibit increased stability against moisture.

Such modifications could further advance progress in nucleic acid chemistry with regard to medical applications. The last few decades have already seen a large number of modifications that have been optimized for various areas of application and technologies [52]. They all attempt to solve fundamental problems in working with nucleic acids, which, depending on the application, can be reduced to cellular uptake, stability in the respective medium, early excretion, unwanted off-target reactions, and the need for complementarity with natural nucleic acids, especially when used in biological systems [53,54,55,56]. To date, these requirements and challenges cannot be solved by a single xenonucleic acid alone, so that dioxazaborocane-modified nucleic acids can become an extension of the existing portfolio [53,55].

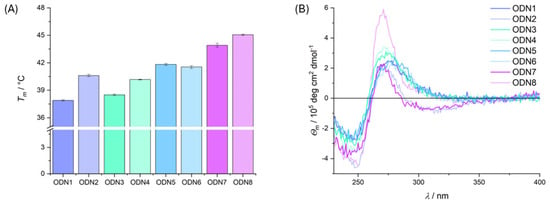

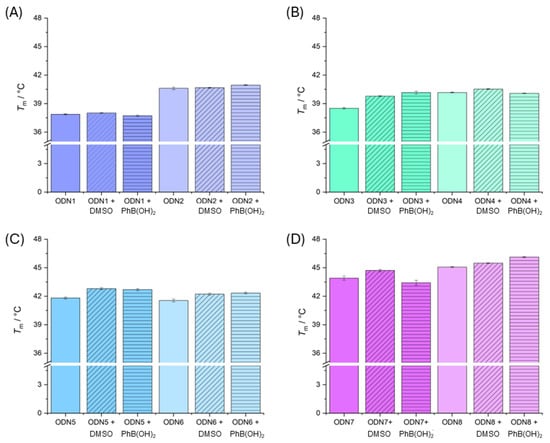

Studies on the formation of boronates have shown that, in addition to the pH value of the solution, the pKa value of the used boronic acid has an influence on the position of the equilibrium [57,58,59,60]. In the case of phenylboronic acid, significantly higher binding constants to a large number of diols have been obtained at higher pH values [60]. For this reason, the diethanolamine-modified oligonucleotides were treated with phenylboronic acid at pH 9.0 and the thermal stability of the duplexes was monitored by temperature-dependent UV/vis spectroscopy (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bar charts of melting temperatures with standard deviation (3σ) for double-stranded oligonucleotides (A) ODN1 and ODN2, (B) ODN3 and ODN4, (C) ODN5 and ODN6 and (D) ODN7 and ODN8 without any additives, with DMSO (0.2%) and with phenylboronic acid in DMSO (0.2%). Measurement conditions: CHES (5 mM, pH 9.0), NaClO4 (150 mM) and DNA (1.0 µM). The concentration in the cases where DMSO was added was kept at 0.2%.

Because phenylboronic acid is poorly soluble in water, it was dissolved in DMSO and added to aqueous oligonucleotide solutions. For comparison, all oligonucleotides were mixed with the same amount of DMSO (0.2%). The addition of DMSO to the solution of natural oligonucleotides has no discernible effect on the melting temperature (Table 2). Similar effects have already been described in the literature when the amount of DMSO added does not exceed 10% [5]. The addition of DMSO to the diethanolamine-modified oligonucleotides has only a slight effect on the melting temperatures of the duplexes ODN3, ODN5 and ODN7. If phenylboronic acid is also added, the melting temperatures do not change within the standard deviation compared to the melting point with DMSO added alone. This suggests that either the dioxazaborocanes have not formed or that any effects are only marginal.

Table 2.

Overview of melting temperatures of used DNA duplexes without additives, with 2 eq. phenylboronic acid per duplex in DMSO (0.2%) and with DMSO (0.2%) only. Measurement conditions: DNA (1.0 µM), NaClO4 (150 mM), CHES (5 mM, pH 9.0).

On the one hand, this may be a result of fraying at the duplex ends, meaning that changes to the terminal base pairs have only a minor effect on thermal stabilization. On the other hand, it could be because dioxazaborocanes are significantly more dynamic in aqueous solution than, for example, analogous MIDA derivatives, and can switch between the open and closed forms, as has already been shown in a study on isolated nucleosides [51]. Similarly, the formation of the corresponding dioxazaborocane may not occur. Although larger amounts of added boronic acid retained the B-DNA structure, they did not cause any change in melting temperatures. However, polymer chemistry has shown that dioxazaborocanes have increased stability in water and are used there to form larger networks [39,40,61,62,63]. Since the stability of the stabilizing B–N bond of the closed form of dioxazaborocanes is also a function of temperature, it may also be the case that hydrolysis increases with rising temperature, so that any dioxazaborocanes that have formed are already hydrolyzed again before the melting point is reached [62].

The incorporated diethanolamine modifier has an influence on the stability of formed duplexes when the adjacent base pair consists of adenine and thymine, which is presumably due to the reduced stability of this base pair compared to the cytosine-guanine base pairing. In general, compatibility of the diethanolamine modifier with the structure of B-DNA is given and can be used as a modifiable site in the future. The formation of dioxazaborocanes with a terminal diethanolamine modification at the strand ends of duplexes could not be detected, as the measurement conditions presumably favor hydrolysis, so that effects on thermal stability could not be identified. However, the isolated diethanolamine derivative showed the formation of the corresponding dioxazaborocane both in solution and in the solid state.

In the future, the modifiability of the diethanolamine motif will be further exploited. In addition, the motif will be incorporated at a central location to gain further insights into the influence on neighboring base pairs and to amplify the effects of the modification on the properties of the duplex more clearly, since internal base pairs are less prone to fraying. Furthermore, the concept of dioxazaborocanes is to be extended to other structural motifs of nucleic acids, such as the backbone, in order to transfer the advantageous properties of dioxazaborocanes as already described for polymers to the nucleic acid realm.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/appliedchem5040040/s1, NMR spectra, HPLC chromatograms, ESI(–)-MS data, CD spectra, UV/vis spectra, crystallographic data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and M.H.; methodology, T.L. and M.H.; validation, T.L. and M.H.; formal analysis, T.L. and M.H.; investigation, T.L. and M.H.; resources, T.L. and M.H.; data curation, T.L. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, T.L.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Münster and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (VCI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CD | circular dichroism |

| CEDIP-Cl | 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite |

| CHES | N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DIPEA | N,N-diisopropylethylamine |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DMTr- | 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl- |

| MES | 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid |

| MOPS | 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid |

| ODN | oligodeoxyribonucleotide |

| Trt | trityl |

| UV/vis | ultraviolet–visible |

References

- Bonner, G.; Klibanov, A.M. Structural stability of DNA in nonaqueous solvents. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2000, 68, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalo, M.N.; Kong, X.; LiWang, A. Sensitivity of hydrogen bonds of DNA and RNA to hydration, as gauged by 1JNH measurements in ethanol-water mixtures. J. Biomol. NMR 2007, 37, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.I.; Sugimoto, N. The structural stability and catalytic activity of DNA and RNA oligonucleotides in the presence of organic solvents. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackl, E.V.; Blagoi, Y.P. Effect of ethanol on structural transitions of DNA and polyphosphates under Ca2+ ions action in mixed solutions. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2000, 47, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minier, M.A.S.; Farah; Lee, A.; Xue, L. Determination of the effect of water-miscible organic solvents on the stability of DNA duplexes via UV thermal denaturation and circular dichroism. J. Undergrad. Chem. Res. 2011, 10, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Beneventi, S.; Onori, G. Effect of ethanol on the thermal stability of tRNA molecules. Biophys. Chem. 1986, 25, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskur, J.; Rupprecht, A. Aggregated DNA in ethanol solution. FEBS Lett. 1995, 375, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Rupprecht, A.; Song, Z.; Piskur, J.; Nordenskiold, L.; Lahajnar, G. A mechanochemical study of MgDNA fibers in ethanol-water solutions. Biophys. J. 1994, 66, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Traganos, F.; Sharpless, T.; Melamed, M.R. DNA denaturation in situ. Effect of divalent cations and alcohols. J. Cell Biol. 1976, 68, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupprecht, A.; Piškur, J.; Schultz, J.; Nordenskiöld, L.; Song, Z.; Lahajnar, G. Mechanochemical study of conformational transitions and melting of Li-, Na-, K-, and CsDNA fibers in ethanol–water solutions. Biopolymers 1994, 34, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Rupprecht, A.; Fritzsche, H. Mechanochemical study of NaDNA and NaDNA-netropsin fibers in ethanol-water and trifluoroethanol-water solutions. Biophys. J. 1995, 68, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.R.; Sambrook, J. Precipitation of DNA with Ethanol. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, 2016, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Cao, B.; Yi, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Luo, S.; Mou, X.; Guo, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. DNA precipitation revisited: A quantitative analysis. Nano Select 2021, 3, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Esposito, D.; Ricchi, L.; Barone, G. The effects of polyols on the thermal stability of calf thymus DNA. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999, 24, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, E.L. Deformation of DNA. III. The effect of glycol and glycerol on the ultraviolet absorbances of DNA. Renaturation by dilution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1961, 6, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Vogt, C.E.; McBrairty, M.; Al-Hashimi, H.M. Influence of dimethylsulfoxide on RNA structure and ligand binding. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 9692–9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockx, J. The influence of strong solutions of uerea and poly alcohols on the spectroscopic behavior of ribonucleic acid and nucleotides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1963, 68, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.; Nielsen, P.E. On the stability of peptide nucleic acid duplexes in the presence of organic solvents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kimura, T.; Iwai, S.; Moritan, T.; Nam, K.; Mutsuo, S.; Yoshizawa, H.; Okada, M.; Furuzono, T.; Fujisato, T.; Kishida, A. Preparation of poly(vinyl alcohol)/DNA hydrogels via hydrogen bonds formed on ultra-high pressurization and controlled release of DNA from the hydrogels for gene delivery. J. Artif. Organs 2007, 10, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Emenuga, M.; Kumar, S.; Lamantia, Z.; Figueiredo, M.; Emrick, T. Designing Synthetic Polymers for Nucleic Acid Complexation and Delivery: From Polyplexes to Micelleplexes to Triggered Degradation. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 4029–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Lee, K.; Li, S. Nucleic Acids Based Polyelectrolyte Complexes: Their Complexation Mechanism, Morphology, and Stability. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 7923–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, M. Compatible solute influence on nucleic acids: Many questions but few answers. Saline Syst. 2008, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, T.; Layh, M.; Hebenbrock, M. One trityl, two trityl, three trityl groups—Structural differences of differently substituted triethanolamines. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 2025, 240, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, A.; Kowerko, D.; Sigel, R.K.O. Explicit analytic equations for multimolecular thermal melting curves. Biophys. J. 2015, 202, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.V.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, Y.D.; Aspnes, D.E. Decoding ‘Maximum Entropy’ Deconvolution. Entropy 2022, 24, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaluzzi, M.J.; Borer, P.N. Revised UV extinction coefficients for nucleoside-5’-monophosphates and unpaired DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APEX5, Version 2023.9.2; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2023.

- SAINT, Version 8.40B; includes Xprep, SADABS and TWINABS; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2001.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS. University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubben, J.; Wandtke, C.M.; Hubschle, C.B.; Ruf, M.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. Aspherical scattering factors for SHELXL—Model, implementation and application. Acta Crystallogr. A 2019, 75, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond—Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization, Crystal Impact; Dr. H. Putz & Dr. K. Brandenburg GbR: Bonn, Germany.

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgarbova, M.; Otyepka, M.; Sponer, J.; Lankas, F.; Jurecka, P. Base Pair Fraying in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of DNA and RNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 3177–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreatta, D.; Sen, S.; Perez Lustres, J.L.; Kovalenko, S.A.; Ernsting, N.P.; Murphy, C.J.; Coleman, R.S.; Berg, M.A. Ultrafast dynamics in DNA: “fraying” at the end of the helix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6885–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, T.; Hepp, A.; Layh, M.; Hebenbrock, M. Anionic Boraza-Crown Ethers. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, T.; Hebenbrock, M. Phenylsilver—An unexpected one-dimensional coordination polymer of silver(I) tetrads. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, R.; Garcia, C.; Mancilla, T.; Wrackmeyer, B. The N-B coordination in hindered cyclic thexylboronic esters derived from diethanolamines. J. Organomet. Chem. 1983, 246, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Yamanishi, M.; Kameyama, A.; Otsuka, H. Reversible modulation of polymer chain mobility by selective cage opening and closing of pendant boratrane units. Polym. J. 2024, 57, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Jing, X. Boronic Ester Based Vitrimers with Enhanced Stability via Internal Boron-Nitrogen Coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 21852–21860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durka, K.; Kaminski, R.; Lulinski, S.; Serwatowski, J.; Wozniak, K. On the nature of the B⋯N interaction and the conformational flexibility of arylboronic azaesters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 13126–13136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Barvik, I.; Luvino, D.; Smietana, M.; Vasseur, J.J. Dynamic and programmable DNA-templated boronic ester formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4193–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.R.; Vasseur, J.J.; Smietana, M. Boron and nucleic acid chemistries: Merging the best of both worlds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5684–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeyron, R.; Martin, A.R.; Jean-Jacques Vasseur, J.-J.V.; Michael Smietana, M.S. DNA-templated borononucleic acid self assembly: A study of minimal complexity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 105587–105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiais, M.; Gimenez Molina, A.; Muller, S.; Vasseur, J.J.; Barvik, I.; Baraguey, C.; Smietana, M. Design and NMR characterization of reversible head-to-tail boronate-linked macrocyclic nucleic acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelievre-Buttner, A.; Schnarr, T.; Debiais, M.; Smietana, M.; Muller, S. Boronic Acid Assisted Self-Assembly of Functional RNAs. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiais, M.; Lelievre, A.; Vasseur, J.-J.; Müller, S.; Smietana, M. Boronic Acid-Mediated Activity Control of Split 10–23 DNAzymes. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiais, M.; Vasseur, J.J.; Smietana, M. Applications of the Reversible Boronic Acids/Boronate Switch to Nucleic Acids. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202200085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, M.; Vasseur, J.J.; Smietana, M. Nuclease stability of boron-modified nucleic acids: Application to label-free mismatch detection. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10604–10608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clave, G.; Reverte, M.; Vasseur, J.J.; Smietana, M. Modified internucleoside linkages for nuclease-resistant oligonucleotides. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 94–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeyron, R.; Vasseur, J.-J.; Baraguey, C.; Smietana, M. Synthesis of 3‘-deoxy-3‘-iminodiacetic acid and 3‘-deoxy-3‘-aminodiethanol thymidine analogues and NMR study of their complexation with boronic acids. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 2468–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epple, S.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Brown, T. Artificial nucleic acid backbones and their applications in therapeutics, synthetic biology and biotechnology. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Witzigmann, D.; Thomson, S.B.; Chen, S.; Leavitt, B.R.; Cullis, P.R.; van der Meel, R. The current landscape of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, P.; Heinemann, I.U.; Fan, C. Editorial: Synthetic Nucleic Acids for Expanding Genetic Codes and Probing Living Cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 720534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.C.; Langer, R.; Wood, M.J.A. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.A. Pushing the Limits of Nucleic Acid Function. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202201737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springsteen, G.; Wang, B. A detailed examination of boronic acid–diol complexation. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 5291–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizer, R.; Tihal, C. Equilibria and reaction mechanism of the complexation of methylboronic acid with polyols. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3243–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorand, J.P.; Edwards, J.O. Polyol Complexes and Structure of the Benzeneboronate Ion. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Springsteen, G.; Deeter, S.; Wang, B. The relationship among pKa, pH, and binding constants in the interactions between boronic acids and diols—It is not as simple as it appears. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 11205–11209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Dong, J.; Xu, C.; Pan, X. N-Coordinated Organoboron in Polymer Synthesis and Material Science. ACS Polymers Au 2022, 3, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros-Sedano, A.; Le Besnerais, B.; Van Zee, N.J.; Nicolaÿ, R. Exploiting Dioxazaborocane Chemistry for Preparing Elastomeric Vitrimers with Enhanced Processability and Mechanical Properties. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 2058–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Aoki, D.; Otsuka, H. Functionalization of amine-cured epoxy resins by boronic acids based on dynamic dioxazaborocane formation. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 5356–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).