New Indices of Arterial Stiffness Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device in Long-Term Japanese Shigin Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participant Characteristics

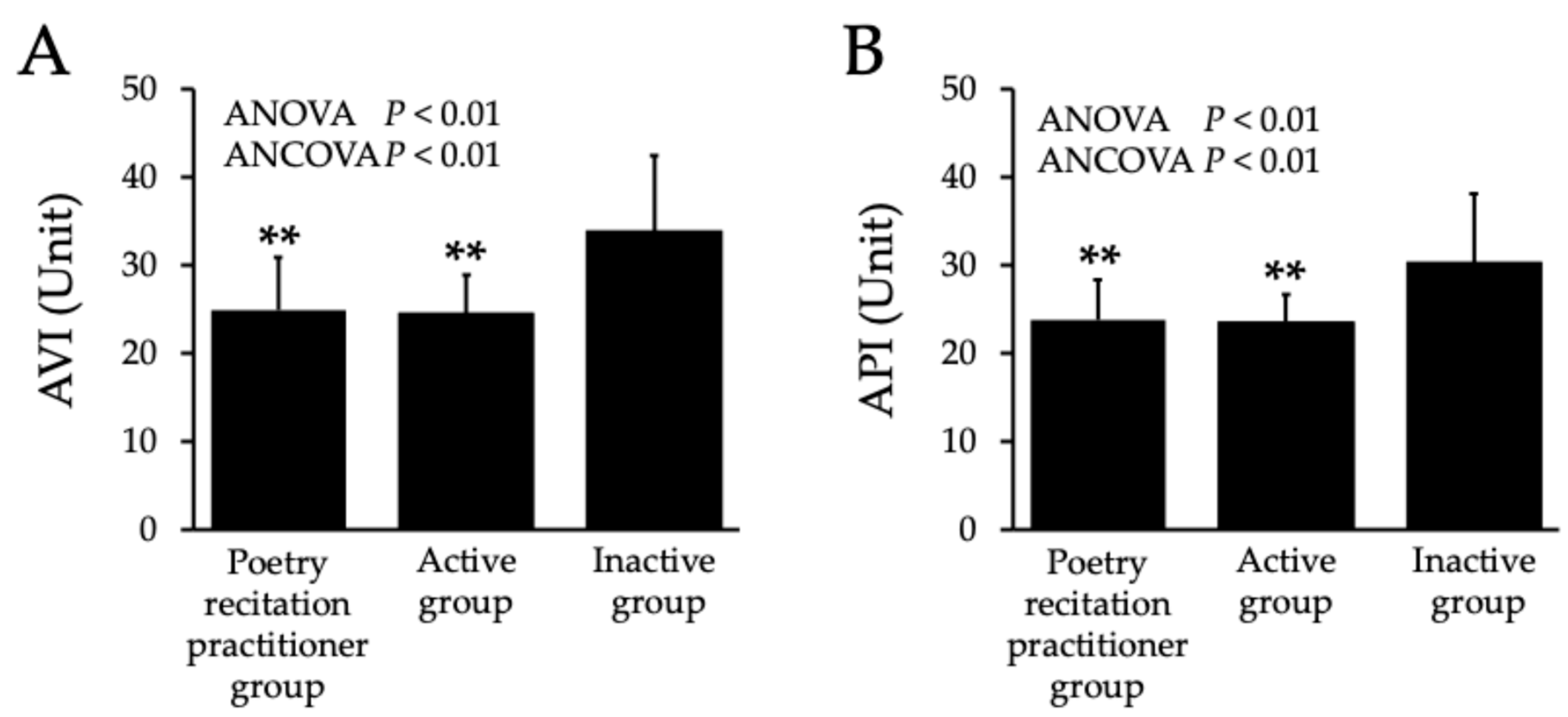

2.2. Arterial Stiffness

2.3. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

2.4. Salivary α-Amylase

2.5. Peak Expiratory Flow

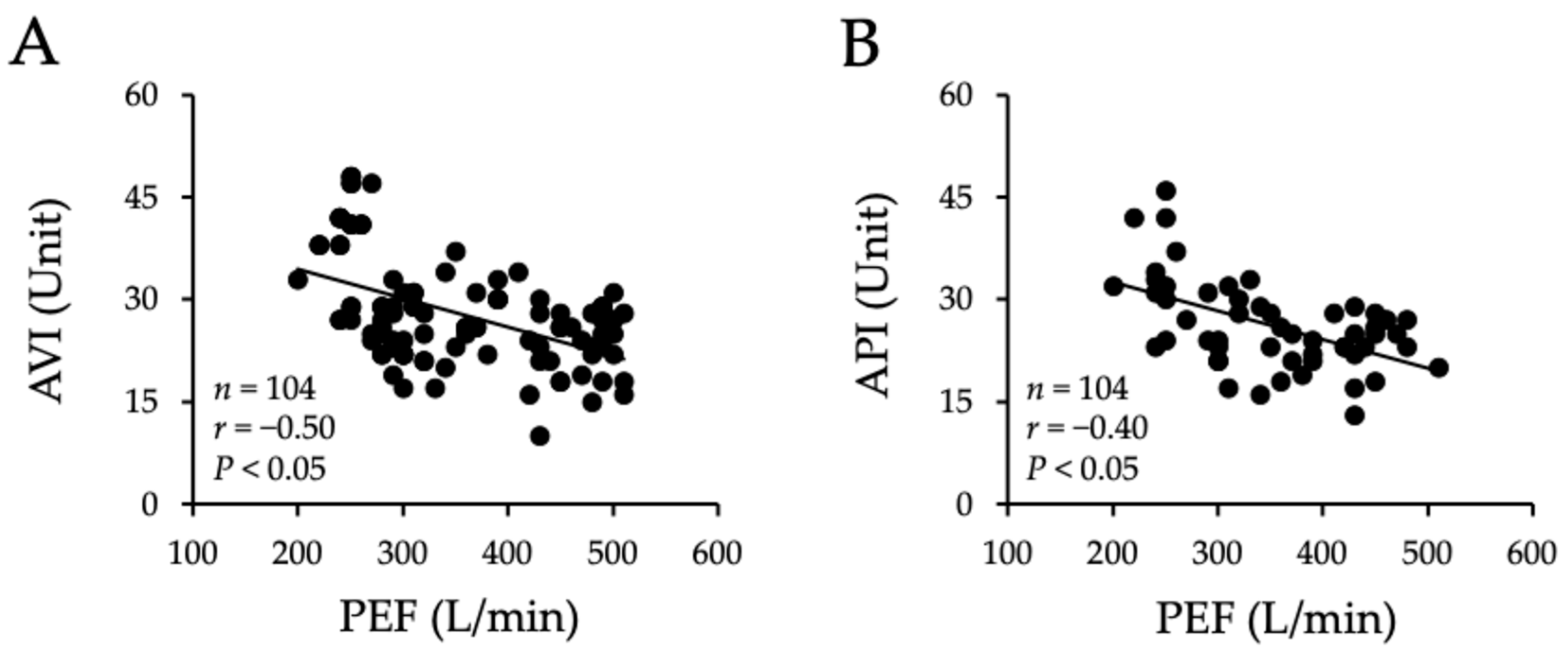

2.6. Correlation Between Arterial Stiffness and Peak Expiratory Flow

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Ethics

4.2. Participants and Group Definitions

4.3. Sample Size Calculation

4.4. Outcomes (Primary and Secondary)

4.5. Measurement Procedures

4.5.1. Arterial Stiffness (AVI and API)

4.5.2. Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

4.5.3. Stress Level (Salivary α-Amylase)

4.5.4. Respiratory Function (PEF)

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Murray, C.J.L.; Roth, G.A. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaborators, Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2350–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Eguchi, E.; Hayashi, F.; Kinuta, M.; Imano, H. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in Japan: An overview study. J. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hametner, B.; Wassertheurer, S.; Mayer, C.C.; Danninger, K.; Binder, R.K.; Weber, T. Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Predicts Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography: A Comparison of Invasive Measurements and Noninvasive Estimates. Hypertension 2021, 77, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Ohishi, M.; Takagi, T.; Terai, M.; Shiota, A.; Hayashi, N.; Rakugi, H.; Ogihara, T. Clinical usefulness and limitations of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in the evaluation of cardiovascular complications in hypertensive patients. Hypertens. Res. 2006, 29, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronck, B.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Avolio, A.P.; Boutouyrie, P.; Guala, A.; Jerončić, A.; Laurent, S.; Barbosa, E.C.D.; Baulmann, J.; Chen, C.-H.; et al. Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology (ARTERY), the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Large Arteries, European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action VascAgeNet, North American Artery Society, ARTERY LATAM, Pulse of Asia, and Society for Arterial Stiffness—Germany-Austria-Switzerland (DeGAG), 2024 Recommendations for Validation of Noninvasive Arterial Pulse Wave Velocity Measurement Devices. Hypertension 2024, 81, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komine, H.; Asai, Y.; Yokoi, T.; Yoshizawa, M. Non-invasive assessment of arterial stiffness using oscillometric blood pressure measurement. Biomed. Eng. Online 2012, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Nakamura, F.; Musha, T.; Kobayashi, Y. Association between novel arterial stiffness indices and risk factors of cardiovascular disease. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, T.; Miura, S.-I.; Suematsu, Y.; Shiga, Y.; Kuwano, T.; Sugihara, M.; Ike, A.; Iwata, A.; Nishikawa, H.; Fujimi, K.; et al. Association of Arterial Pressure Volume Index With the Presence of Significantly Stenosed Coronary Vessels. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, S.; Tomiyama, H.; Kimura, K.; Matsumoto, C.; Shiina, K.; Yamashina, A. Comparison of the clinical significance of single cuff-based arterial stiffness parameters with that of the commonly used parameters. J. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, P.; Xu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y.; Liang, F.; Yin, Z. Non-Invasive Assessment of Early Atherosclerosis Based on New Arterial Stiffness Indices Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2017, 241, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, F.; Lu, J. Threshold values of brachial cuff-measured arterial stiffness indices determined by comparisons with the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity: A cross-sectional study in the Chinese population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1131962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, M.; Sha, L.; Cao, M.; Tong, L.; Chen, Q.; Shen, C.; Du, L.; Liu, L.; Li, Z. Increased arterial pressure volume index and cardiovascular risk score in China. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Tong, L.; Shen, C.; Du, L.; Mao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Z. Association of Arterial Stiffness Indices with Framingham Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki-Nakashima, R.; Kino, T.; Chen, L.; Doi, H.; Minegishi, S.; Abe, K.; Sugano, T.; Taguri, M.; Ishigami, T. Successful prediction of cardiovascular risk by new non-invasive vascular indexes using suprasystolic cuff oscillometric waveform analysis. J. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Du, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Feng, L.; Yu, L. Effects of exercise on pulse wave velocity in hypertensive and prehypertensive patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1504632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, R.; Iwanuma, S.; Ohashi, N.; Hashiguchi, T. New indices of arterial stiffness measured with an upper-arm oscillometric device in active versus inactive women. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, T.; Elliot, C.A.; Stoner, L.; Higgins, S.; Paterson, C.; Hamlin, M.J. Association between Yoga Participation and Arterial Stiffness: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Mendiratta, A.; Banga, A.; Bucharles, A.; Victoria, P.; Kamaraj, B.; Qasba, R.K.; Bansal, V.; Thimmapuram, J.; Pargament, R.; et al. Effect of breathing exercises on blood pressure and heart rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2024, 20, 200232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, T.; Obmiński, Z.; Waleriańczyk, W.; Klusiewicz, A. The Acute Effect of Respiratory Muscle Training on Cortisol, Testosterone, and Testosterone-to-Cortisol Ratio in Well-Trained Triathletes-Exploratory Study. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2025, 331, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentikäinen, E.; Pitkäniemi, A.; Siponkoski, S.-T.; Jansson, M.; Louhivuori, J.; Johnson, J.K.; Paajanen, T.; Särkämö, T. Beneficial effects of choir singing on cognition and well-being of older adults: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Shi, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, K.; Chen, X. Effect of religion on hypertension in adult Buddhists and residents in China: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, L.; Sleight, P.; Bandinelli, G.; Cencetti, S.; Fattorini, L.; Wdowczyc-Szulc, J.; Lagi, A. Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: Comparative study. BMJ 2001, 323, 1446–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, A.A. Scientific Evidence of Health Benefits by Practicing Mantra Meditation: Narrative Review. Int. J. Yoga 2022, 15, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihon Ginkenshibu Shinkōkai (Japan Ginkenshibu Promotion Foundation), FY2025 Project Plan and Budget. n.d. Available online: https://www.ginken.or.jp/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/%E4%BB%A4%E5%92%8C%EF%BC (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Liu, H.; Shivgulam, M.E.; Schwartz, B.D.; Kimmerly, D.S.; O’Brien, M.W. Impact of exercise training on pulse wave velocity in healthy and clinical populations: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023, 325, H933–H948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D.R.; Doma, K.; Leicht, A.S. Acute Effects of Exercise Mode on Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection in Healthy Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, T.; Amiya, E.; Ando, J.; Watanabe, M.; Murasawa, T.; Komuro, I. Different Contributions of Physical Activity on Arterial Stiffness between Diabetics and Non-Diabetics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomoto, A.; Deguchi, J.; Fukuda, R.; Yotsumoto, T.; Toyonaga, T. Age-Specific Determinants of Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity among Male Japanese Workers. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2021, 253, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Fujimoto, N.; Hastings, J.L.; Carrick-Ranson, G.; Bhella, P.S.; Hearon, C.M.; Levine, B.D. The effect of lifelong exercise frequency on arterial stiffness. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Kasahara, Y.; Ikeo, T.; Asaki, K.; Sato, K.; Matsui, T.; Iwanuma, S.; Ohashi, N.; Hashiguchi, T. Effects of different intensities and durations of aerobic exercise training on arterial stiffness. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2020, 32, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Biradar, M.S.; Khode, V.; Vadiraja, H.S.; Patil, N.G.; Raghavendra, R.M. Effectiveness of yoga on arterial stiffness: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craighead, D.H.; Heinbockel, T.C.; Freeberg, K.A.; Rossman, M.J.; Jackman, R.A.; Jankowski, L.R.; Hamilton, M.N.; Ziemba, B.P.; Reisz, J.A.; D’Alessandro, A.; et al. Time-Efficient Inspiratory Muscle Strength Training Lowers Blood Pressure and Improves Endothelial Function, NO Bioavailability, and Oxidative Stress in Midlife/Older Adults With Above-Normal Blood Pressure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, C.M.; Cress, M.E.; McCully, K.K. The influence of physical activity and yoga on central arterial stiffness. Dyn. Med. 2008, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.B.; Plentz, R.D.M.; Stein, C.; Casali, K.R.; Arena, R.; Lago, P.D. Inspiratory Muscle Training Reduces Blood Pressure and Sympathetic Activity in Hypertensive Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.N.; Porta, C.; Casucci, G.; Casiraghi, N.; Maffeis, M.; Rossi, M.; Bernardi, L. Slow breathing improves arterial baroreflex sensitivity and decreases blood pressure in essential hypertension. Hypertension 2005, 46, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, C.; Marques, J.R.; de Souza, L.A.; Dartora, D.R.; Eibel, B.; Boll, L.F.C.; Goldmeier, S.N.; Dias, D.; De Angelis, K.; Irigoyen, M.C. Additional Improvement of Respiratory Technique on Vascular Function in Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women Following Yoga or Stretching Video Classes: The YOGINI Study. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Huang, J.; Gao, D.; Zeng, S.; Tang, S.; Chang, Z.; Wen, C.; Zhang, M.; Hu, M.; Wei, G.-X. Effects of mind-body practice on arterial stiffness, central hemodynamic parameters and cardiac autonomic function of college students. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 45, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Dinenno, F.A.; Seals, D.R. Reductions in central arterial compliance with age are related to sympathetic vasoconstrictor nerve activity in healthy men. Hypertens. Res. 2017, 40, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, H.; Hamaoka, T.; Murai, H.; Hirai, T.; Mukai, Y.; Kusayama, T.; Takashima, S.; Kato, T.; Takata, S.; Usui, S.; et al. Relationships between muscle sympathetic nerve activity and novel indices of arterial stiffness using single oscillometric cuff in patients with hypertension. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettermann, H.; Von Bonin, D.; Frühwirth, M.; Cysarz, D.; Moser, M. Effects of speech therapy with poetry on heart rate rhythmicity and cardiorespiratory coordination. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002, 84, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, D.J.; Worhunsky, P.D.; Pilver, C.E.; Brewer, J.A. Meditation-induced changes in high-frequency heart rate variability predict smoking outcomes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Di Luciano, C.; Chiaramonte, I.; Serra, A.; Bonfiglio, M. Multi-disciplinary clinical protocol for the diagnosis of bulbar amyotrophic lateral sclerosisProtocolo clínico multi-disciplinar para el diagnóstico de la esclerosis lateral amiotrófica bulbar. Acta Otorrinolaringol. 2019, 70, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamis, A.; Krawiec, J.T.; Vorp, D.A. Elastin and collagen fibre microstructure of the human aorta in ageing and disease: A review. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20121004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, C.D.; Neutel, C.H.G.; De Meyer, G.R.Y.; Martinet, W.; Guns, P.-J. Unravelling the impact of active and passive contributors to arterial stiffness in male mice and their role in vascular aging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyner, M.J.; Baker, S.E. Take a Deep, Resisted, Breath. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e022203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, R.J.S.; Band, G.P.H. Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnon, V.; Dutheil, F.; Vallet, G.T. Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, A.; Nazim, S.; Sharma, A.; De, A.; Singh, V.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, D.; Varsha, C.S.; Jani, P. Impact of Regular Breathing Exercises on Blood Pressure Phenotypes and BMI in Young Male Individuals: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e90027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.J.; Maiorana, A.; O’Driscoll, G.; Taylor, R. Effect of exercise training on endothelium-derived nitric oxide function in humans. J. Physiol. 2004, 561, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebauer, J.; Cooke, J.P. Cardiovascular effects of exercise: Role of endothelial shear stress. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996, 28, 1652–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhen, K.; Ren, S.; Lv, Y.; Yu, L. Effect of continuous aerobic exercise on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1043108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoian, D.; Mazzone, J.L.; Craighead, D.H.; Bailey, E.F. Acute inspiratory resistance training enhances endothelium-dependent dilation and retrograde shear rate in healthy young adults. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e15943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring the potential of vagus nerve stimulation in treating brain diseases: A review of immunologic benefits and neuroprotective efficacy. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Kanemori, T.; Kanemaru, M.; Takai, N.; Mizuno, Y.; Yoshida, H. Performance evaluation of salivary amylase activity monitor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004, 20, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measuring Your Peak Flow Rate. 2025. Available online: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/asthma/treatment/devices/peak-flow (accessed on 20 September 2025).

| Poetry Recitation Practitioner Group | Active Group | Inactive Group | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 35 | 35 | 34 | 0.89 |

| Age (years) | 75.2 ± 7.2 | 74.4 ± 4.2 | 74.7 ± 8.3 | 0.97 |

| Height (cm) | 158.6 ± 4.8 | 159.0 ± 7.9 | 158.9 ± 7.6 | 0.97 |

| Body weight (kg) | 56.1 ± 4.8 | 56.5 ± 5.6 | 56.1 ± 5.6 | 0.94 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 ± 1.1 | 22.3 ± 0.7 | 22.2 ± 0.9 | 0.87 |

| Daily total steps | 3992.2 ± 1189.1 | 10,367.3 ± 1814.6 ** | 4071.9 ± 1692.7 | <0.01 |

| Daily living activity (kcal/day) | 240.9 ± 78.8 | 323.3 ± 88.5 ** | 232.7 ± 80.3 | <0.01 |

| Daily step activity (kcal/day) | 146.9 ± 44.7 | 386.7 ± 87.8 ** | 152.0 ± 69.1 | <0.01 |

| Shigin practice duration (years) | 22.7 ± 11.5 ** | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | <0.01 |

| Sleep time (hours/day) | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 0.98 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 17/18 | 17/18 | 18/16 | 0.91 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Medication | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Poetry Recitation Practitioner Group | Active Group | Inactive Group | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brachial SBP (mmHg) | 121.5 ± 13.2 ** | 121.1 ± 6.1 ** | 130.3 ± 8.2 | <0.01 |

| Brachial MBP (mmHg) | 88.0 ± 7.8 ** | 89.4 ± 5.0 * | 94.6 ± 9.2 | <0.01 |

| Brachial DBP (mmHg) | 71.3 ± 8.3 * | 73.1 ± 6.1 | 76.7 ± 11.3 | <0.01 |

| Brachial PP (mmHg) | 50.2 ± 13.8 | 48.8 ± 7.4 | 53.7 ± 10.3 | 0.35 |

| CSBP (mmHg) | 136.1 ± 12.2 ** | 136.8 ± 5.8 ** | 148.7 ± 10.0 | <0.01 |

| HR (beats/min) | 68.5 ± 5.5 | 68.8 ± 4.2 | 69.4 ± 8.5 | 0.91 |

| Salivary α-Amylase (KU/L) | 22.1 ± 6.6 ** | 21.1 ± 5.6 ** | 33.1 ± 5.3 | <0.01 |

| Peak expiratory flow (L/min) | 389.7 ± 70.2 ** | 393.8 ± 103.8 ** | 282.3 ± 50.9 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kobayashi, R.; Seki, S.; Niu, K.; Negoro, H. New Indices of Arterial Stiffness Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device in Long-Term Japanese Shigin Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study. Physiologia 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia6010003

Kobayashi R, Seki S, Niu K, Negoro H. New Indices of Arterial Stiffness Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device in Long-Term Japanese Shigin Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study. Physiologia. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKobayashi, Ryota, Shotaro Seki, Kun Niu, and Hideyuki Negoro. 2026. "New Indices of Arterial Stiffness Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device in Long-Term Japanese Shigin Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study" Physiologia 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia6010003

APA StyleKobayashi, R., Seki, S., Niu, K., & Negoro, H. (2026). New Indices of Arterial Stiffness Measured with an Upper-Arm Oscillometric Device in Long-Term Japanese Shigin Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Study. Physiologia, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia6010003