Abstract

Microalgae are sustainable sources of bioactive compounds with broad hepato-protective potential. This review synthesizes evidence for five major classes—carotenoids such as astaxanthin and fucoxanthin, polysaccharides such as paramylon and fucoidan, phycobiliproteins such as phycocyanin, omega-3 fatty acids, and phenolic extracts—linking their actions to key liver injury mechanisms. Preclinically, these compounds enhance antioxidant defenses, improve mitochondrial function, suppress inflammatory signaling, regulate lipid metabolism, modulate the gut–liver axis, and inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation, thereby attenuating fibrosis. Consistent benefits are observed in models of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease, drug-induced injury, ischemia–reperfusion, and fibrosis, with marked improvements in liver enzymes, oxidative stress, inflammation, steatosis, and collagen deposition. Emerging evidence also highlights their roles in regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Despite their promise, translational challenges include compositional variability, a lack of standardized quality control, limited safety data, and few rigorous human trials. To address these challenges, we propose a framework integrating multi-omics and AI-assisted strain selection with specification-driven quality control and formulation-aware designs—such as lipid carriers for carotenoids or rational combinations like fucoxanthin with low-molecular-weight fucoidan. Future priorities include composition-defined randomized controlled trials in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and drug-induced liver injury; harmonized material specifications; and multi-constituent interventions that synergistically target oxidative, inflammatory, metabolic, and fibrotic pathways.

1. Introduction

Liver diseases arise from converging processes—metabolic overload, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrogenic remodeling. Together, these mechanisms drive progression from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Microalgae provide a sustainable source of bioactives—including carotenoids, polysaccharides, phycobiliproteins, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and phenolic/phlorotannin-rich constituents—many of which target these pathways. These compounds are increasingly explored in functional food development and translational biomedical research [1,2,3,4].

1.1. Microalgae in Functional Foods and Drug Development

Microalgae are photosynthetic microorganisms that inhabit diverse aquatic environments and synthesize a wide array of bioactive molecules relevant to human health. Major classes include carotenoids, polysaccharides, phycobiliproteins, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and phenolic/phlorotannin-rich compounds P1-M3. Many of these exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and metabolism-regulating activities [1,2,3,4]. These properties make microalgae particularly attractive for liver-related applications, where oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation play central pathogenic roles [1,3].

Microalgal ingredients are already embedded in consumer and clinical-adjacent markets. Illustrative examples include the following: (i) whole-biomass powders/tablets from Arthrospira (formerly known as Spirulina) and Chlorella used in functional foods and supplements worldwide; (ii) algal long-chain n-3 oils (EPA/DHA; commonly from Nannochloropsis) incorporated into infant formula, medical foods, and adult nutraceuticals, supported by multiple U.S. FDA GRAS notices and EU opinions [5,6,7,8,9]; (iii) carotenoid extracts such as astaxanthin from Haematococcus lacustris (previous as H. pluvialis) [10] in capsules, beverages, and shots, with safety specifications and adult intake limits clarified by EFSA [11,12]; (iv) purified C-phycocyanin from Arthrospira used both as a food-grade colorant and as a bioactive in RTD formats—listed as a color additive exempt from certification in the U.S. [13,14] while requiring EU-specific compliance paths; and (v) β-1,3-glucan (paramylon) from Euglena gracilis, commercialized in Japan in beverages, sachets, and snacks, with early human data indicating improvements in metabolic readouts relevant to liver health [15]. Emerging evaluations also support EPA-rich oils derived from Nannochloropsis gaditana as novel lipid ingredients [16].

For instance, Euglena gracilis produces paramylon (a β-1,3-D-glucan), described as a next-generation prebiotic and is associated with improvements in metabolic and inflammatory markers in preclinical models [17,18,19,20,21]. Haematococcus lacustris is a rich source of astaxanthin, a carotenoid with potent antioxidant and anti-fibrotic effects; both cell-based studies and reviews support its ability to suppress hepatic stellate-cell activation [22,23]. Additionally, microalgae such as Nannochloropsis and Phaeodactylum tricornutum provide renewable sources of n-3 PUFAs and standardized extracts that modulate lipid metabolism in lipotoxic or steatotic models, consistent with PUFA-linked antifibrotic and metabolic pathways [24,25,26].

Microalgal biomass and extracts are used in functional foods and nutraceuticals across multiple markets, and product development pipelines increasingly prioritize composition-defined materials with verified bioactivity. However, species/strain diversity and variability in culture and processing conditions demand standardization and rigorous characterization—including identity-and-potency profiling and safety assessments—to ensure reproducibility and translational viability [1,2,4].

1.2. Global Burden of Liver Diseases

Liver diseases impose a substantial and growing global health burden. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 analysis estimated that cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases caused ~1.5 million deaths worldwide in 2019, with many regions showing rising mortality and disability over the past three decades (GBD 2019 Cirrhosis Collaborators) [15,16]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease affects roughly 25–30% of adults globally, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is present in about 4–6% of the general population, making metabolic liver disease a leading driver of future cirrhosis and transplantation needs [27,28]. Liver cancer remains a major endpoint of chronic liver injury: in 2020, there were ~905,700 new cases and ~830,200 deaths worldwide, ranking sixth for incidence and third for cancer-related mortality [29]. In parallel, alcohol-associated liver disease continues to contribute markedly to cirrhosis deaths and disability-adjusted life years, with alcohol-attributable liver outcomes increasing in several regions across recent GBD cycles [30].

Together, these data underscore the urgency of effective preventive and therapeutic strategies, and provide epidemiological rationale for exploring microalgae-derived interventions that target oxidative stress, inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and fibrogenesis [31].

1.3. Objective and Structure of This Review

The expanding literature on microalgae-derived bioactive compounds—including carotenoids, polysaccharides, phycobiliproteins, n-3 PUFAs, and phenolic/phlorotannin-rich constituents—demonstrates consistent hepatoprotective effects across various injury models, including alcoholic liver disease, NAFLD/NASH, drug-induced hepatotoxicity, and ischemia–reperfusion injury [1,3,24,25,26,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Building on previous reviews that link algal metabolites to human health and liver pathology, this article consolidates in vitro, in vivo, and nutritional intervention data to deliver a mechanistic and translational synthesis [1,2,3,4].

We begin by categorizing the principal classes of microalgal bioactives and representative species: carotenoids such as astaxanthin, fucoxanthin from H. lacustris and P. tricornutum, polysaccharides such as paramylon from E. gracilis, fucoidan from brown algae, laminarin, phycobiliproteins such as phycocyanin from Spirulina/Arthrospira, PUFAs such as EPA/DHA from Nannochloropsis and Phaeodactylum, and phenolic/phlorotannin-rich extracts. For each class, we outline the major antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, lipid-regulatory, and anti-fibrotic mechanisms involved, citing representative pathways and endpoints—such as Nrf2/HO-1, NF-κB/TLR4 signaling, HSC activation, collagen deposition, and serum transaminase levels [3,18,21,22,23,24,25,26,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

We then address translational challenges that affect reproducibility and clinical relevance, including (i) compositional variability across species, strains, and culture conditions; (ii) the need for standardized characterization and safety data in functional-food and nutraceutical development; and (iii) the role of multi-omics and computational screening in prioritizing high-value strains, compounds, and production systems [1,2,3,4,52]. Where relevant, we highlight formulation strategies—such as combining sulfated polysaccharides with carotenoids or leveraging the prebiotic properties of paramylon—that may enhance bioavailability and target the gut–liver axis as a modifiable therapeutic interface [17,24,25,50].

Compared with higher plants or macroalgae, microalgae offer key advantages: rapid growth, scalable and controlled cultivation, and greater amenability to strain and process optimization. These features position microalgae as a promising platform at the intersection of nutrition, pharmacology, and biotechnology [1,2,4,53]. Future directions will be increasingly interdisciplinary, incorporating systems biology, omics-guided profiling, and AI/ML-driven design pipelines to accelerate progress from strain to clinical solution [4,52,54].

2. Microalgae-Derived Bioactive Compounds for Liver Protection

2.1. Carotenoids (Astaxanthin, β-Carotene, Lutein, Fucoxanthin)

Carotenoids are lipid-soluble pigments produced by many microalgae, with astaxanthin, fucoxanthin, β-carotene, and lutein among the best studied for hepatoprotection. These compounds exhibit potent antioxidant and cytoprotective activities by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), stabilizing membranes, activating endogenous antioxidant pathways, and preserving mitochondrial integrity in liver-related models [22,23,25,32,33,34,41,42,43,44,45,55,56,57].

Astaxanthin, predominantly derived from H. lacustris, suppresses pro-inflammatory signaling, inhibits hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation, and enhances mitochondrial function, thereby counteracting fibrogenic processes [22,23,41]. Also, many other microalgae such as Euglena sanguinea, Euglena rubida, Ettlia carotinosa and Chlainomonas accumulate astaxanthin but with limited industrial production [58].

Fucoxanthin, abundant in diatoms such as P. tricornutum, activates protective signaling cascades—including PI3K/AKT–Nrf2 and AMPK/Nrf2/TLR4—and reduces HSC activation. Studies using composition-defined extracts further support efficacy through improved metabolic outcomes [42,43,44,45,57].

β-Carotene and lutein, found in microalgae such as Dunaliella salina (β-carotene) and Chlorella (lutein) as reported [59,60], mitigate xenobiotic-induced liver damage by reducing lipid peroxidation, restoring antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, GSH, CAT), and preserving mitochondrial function. Carotenoid-enriched microalgal formulations lower serum transaminase levels and reduce fibrosis in vivo [32,33,34,55,56].

Taken together, these carotenoids exert hepatoprotective effects through ROS scavenging, Nrf2/Keap1 pathway activation, NF-κB inhibition, mitochondrial protection, and antifibrotic action—supporting their potential use in nutraceuticals and functional foods for liver disorders driven by oxidative stress [22,23,25,32,33,34,41,42,43,44,45,55].

2.2. Polysaccharides (Paramylon, Fucoidan, Laminarin)

Microalgae and macroalgae produce a wide array of structurally diverse polysaccharides with demonstrated hepatoprotective activity. Among them, paramylon, fucoidan, and laminarin are well studied and exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antifibrotic properties across preclinical models [18,19,35,36,40,46,47,48,49,50,61,62].

Paramylon (β-1,3-D-glucan) from E. gracilis improves metabolic and inflammatory parameters, upregulates of SIRT1, and suppresses inflammatory signaling. Nanostructured paramylon further reduces α-SMA and collagen deposition in fibrotic models, indicating a direct role in fibrosis attenuation [18,19,21,46,62,63,64,65].

Fucoidan, a sulfated fucose-rich polysaccharide from brown algae, protects against liver injury in models of alcohol exposure, ischemia–reperfusion, and xenobiotic toxicity. Mechanisms include Nrf2/HO-1 activation, anti-inflammatory signaling, and mitochondrial quality control. When combined with other bioactives, fucoidan enhances metabolic outcomes, underscoring its potential in multi-component formulations [35,36,40,47,48,50,61,66,67].

Laminarin (β-1,3/1,6-glucan) alleviates alcohol-induced liver injury in vivo by reducing oxidative stress and restoring hepatic antioxidant enzyme activity, supporting its broader hepatoprotective potential among algal glucans [68].

In summary, algae-derived polysaccharides target multiple interconnected mechanisms—oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrogenesis, and gut–liver axis regulation—positioning them as promising multi-target candidates for next-generation liver protection strategies [18,19,21,35,36,40,46,47,48,49,50,61,62].

2.3. Phycobiliproteins (Phycocyanin)

Phycobiliproteins—particularly C-phycocyanin (C-PC) from cyanobacteria such as Arthrospira and from rhodophytes [69]—are water-soluble pigment–protein complexes with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that support hepatoprotection across diverse liver-injury models. Isolated C-PC lowers serum transaminases, reduces lipid peroxidation, restore endogenous antioxidant systems (e.g., SOD, CAT, GSH), and improves liver histopathology in toxin- and stress-induced models [37,70,71,72]. In cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity, purified phycocyanin shows strong antioxidant capacity and prevents liver damage. Similarly, in radiation-induced hepatic injury, it reduced ALT/AST levels and oxidative markers while attenuating apoptosis—demonstrating a broad cytoprotective profile [37,72]. In a dietary model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, phycocyanin improved hepatic steatosis and inflammation, further supporting its relevance in metabolic liver disease [70].

Beyond purified C-PC, whole Arthrospira biomass—naturally enriched in phycocyanin and other micronutrients—shows hepatoprotection in toxicant-induced models. In rats exposed to CCl4, Arthrospira platensis preparations (including phenolic-enriched fractions) reduced oxidative stress and histological damage [73]. Arthrospira also protects against cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity—especially when co-administered with vitamin C—and against acrylamide-induced liver injury, in line with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [74,75]. Additional studies report protective effects in acetaminophen-induced hepato-renal injury and chemopreventive activity in rodent models, highlighting its translational potential [38,76]. A clinically oriented review of blue-green algae further summarizes benefits relevant to NAFLD risk factors—including lipid imbalance, oxidative stress, and inflammation—broadening the context for C-PC applications in liver health [77].

Mechanistically, both C-PC and Arthrospira biomass act via complementary pathways:

- 1.

- Direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species and enhancement of endogenous antioxidant defenses (SOD, CAT, GSH);

- 2.

- The suppression of NF-κB-mediated inflammatory signaling;

- 3.

- The attenuation of hepatocyte apoptosis and preservation of mitochondrial integrity;

- 4.

- The improvement in steatosis and inflammatory cell infiltration in metabolic settings [37,70,72,77].

While phycocyanin is likely the major active, other Arthrospira components may augment hepatoprotection by modulating lipid metabolism and influencing the gut–liver axis, as suggested in metabolic disease models [70,78]. Collectively, these data position C-PC as a lead algal protein for hepatoprotection, with Arthrospira biomass offering a practical, multi-component nutraceutical for prevention or adjunctive management of liver injury [37,38,70,73,74,75,76,77].

2.4. PUFAs (DHA, EPA)

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)—particularly the long-chain n-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)—play central roles in regulating hepatic lipid metabolism and inflammation. Microalgae such as Nannochloropsis and P. tricornutum provide sustainable and composition-defined sources of these bioactive lipids for liver-related applications [24,25]. Furthermore, microalgae like Lobosphaera incisa represent a unique source of arachidonic acid (ARA), an important n-6 PUFA and a key precursor for eicosanoid synthesis [79], underscoring the broader potential of microalgae as producers of diverse functional lipids.

Mechanistic studies have shown that DHA and EPA activate PPARα and AMPK signaling, suppress SREBP-1c/ACC/FAS-driven lipogenesis, and enhance mitochondrial β-oxidation. These effects collectively reduce hepatic triglyceride accumulation and improve insulin sensitivity [20,26,80]. In preclinical models of NAFLD and high-fat diet (HFD)–induced liver injury, PUFA-rich microalgal preparations reduce steatosis and inflammatory infiltration, while improving serum lipid profiles and hepatic fat handling [20,24,25]. Anti-fibrotic effects are also reported, including suppression of hepatic stellate cell activation and reduced collagen deposition [26,80].

Emerging evidence suggests that synergy with other microalgal metabolites may enhance these effects. Co-formulations with carotenoids such as fucoxanthin or sulfated polysaccharides such as fucoidan yield additive or synergistic benefits in models of diet-induced liver injury—especially regarding lipid metabolism and oxidative balance [50,55].

In summary, microalgae-derived EPA and DHA address two core drivers of liver disease progression—lipid accumulation and chronic inflammation—while offering a scalable, composition-controlled alternative to traditional fish oil sources [20,24,25,26,50,55,80].

2.5. Phenolic Compounds (Polyphenols, Phlorotannins)

Phenolic compounds—including phenolic acids, flavonoids, and algal-specific phlorotannins—are multifunctional antioxidants with additional anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic activities relevant to liver protection. Reviews of algae and microalgae consistently identify phenolics as central contributors to their bioactivity profiles—alongside carotenoids, polysaccharides, and PUFAs—highlighting their roles in ROS scavenging, Nrf2/Keap1 modulation, and suppression of NF-κB-driven cytokine responses [1,3,49].

Translationally, phenolic-rich algal extracts can be produced Via food-grade extraction methods, standardized using total phenolic/phlorotannin content and chemical fingerprints, and incorporated into functional formulations targeting liver health [1,3,49].

In vivo studies from both microalgal and macroalgal sources support the hepatoprotective potential of phenolic-enriched extracts. For example, an acetone extract of the diatom Amphora coffeaeformis—characterized by high phenolic content—alleviated paracetamol-induced liver injury in rats by lowering serum transaminases, restoring antioxidant enzymes, and improving histological features [34]. Similarly, phenolic-enriched preparations from Arthrospira platensis protected against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity by reducing lipid peroxidation and enhancing hepatic antioxidant status [73]. In metabolic models, ethanol extracts of Isochrysis zhangjiangensis ameliorated alcohol-induced liver damage and corrected gut microbiota imbalances, highlighting the potential of phenolic-rich microalgal compositions to modulate the gut–liver axis [51]. Although derived from a green macroalga, Caulerpa lentillifera improved NAFLD-like phenotypes and remodeled the gut microbiota in rats, suggesting a mechanistic analog for microalgal phenolic interventions—particularly in fiber- and polyphenol-enriched matrices [81].

Mechanistically, phenolics and phlorotannins act at multiple levels:

- 1.

- Direct ROS scavenging and metal chelation to reduce lipid peroxidation;

- 2.

- The activation of endogenous antioxidant systems such as Nrf2/HO-1;

- 3.

- The inhibition of NF-κB and TLR-mediated inflammatory signaling;

- 4.

- Downstream effects on hepatic stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix turnover, contribute to reduced fibrogenesis [1,3,49].

Several reviews also highlight potential synergy between phenolics, carotenoids, and PUFAs within standardized microalgal extracts, suggesting that multi-constituent formulations may outperform than single-compound approaches in complex liver injury scenarios [1,3]. For example, phenolic-rich extracts from N. gaditana have demonstrated strong antioxidant capacity and favorable biological activity in nutritional studies, further supporting their development as functional food components for managing hepatic oxidative and inflammatory stress [24].

In summary, microalgal phenolics—and related phlorotannins—complement other key bioactives (carotenoids, polysaccharides, PUFAs) by offering potent redox modulation and inflammation control, two mechanisms central to limiting progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. To ensure reproducibility and translational viability, standardization through quantitative profiling (e.g., total phenolics, phlorotannins, chemical signatures) and mechanistic validation (e.g., Nrf2, NF-κB, stellate cell markers) will be essential [1,3,24,49,51,82,83].

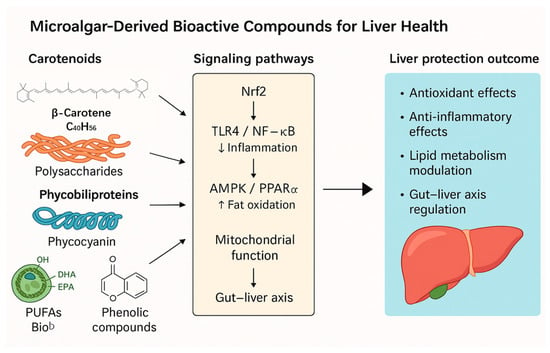

A comparative summary of compound classes, representative sources, mechanisms, and target pathologies is provided in Table 1, and a visual overview of microalgal bioactives and associated hepatic signaling pathways is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Representative classes of microalgae-derived bioactive compounds, sources, mechanisms, and targeted liver pathologies. An upward arrow indicates an increase in substance concentration, while a downward arrow indicates a decrease in substance concentration.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic modules linking microalgal actives to hepatoprotection. The figure illustrates how five major classes of microalgal bioactives—carotenoids (e.g., astaxanthin, fucoxanthin), polysaccharides (paramylon, fucoidan, laminarin), phycobiliproteins (phycocyanin), n-3 PUFAs (EPA/DHA), and phenolic/phlorotannin-rich extracts—exert protective effects in the liver through shared and distinct molecular pathways. Key signaling nodes include Nrf2/HO-1 (antioxidant defense), TLR4/NF-κB (anti-inflammatory signaling), and AMPK/PPARα (lipid metabolism regulation). These compounds also support mitochondrial function, modulate cell death pathways (e.g., ferroptosis, apoptosis), and influence the gut–liver axis via microbiota and barrier integrity. Collectively, these actions contribute to reduced oxidative stress, inflammation, steatosis, and fibrosis—central processes in liver injury and disease progression. Representative references: [22,23,24,25,26,32,33,34,35,36,37,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,55,56,57,61,62,66,70,73,74,76,80].

The following figure serves as a summary of key concepts discussed in this section.

3. Mechanistic Modules Underpinning Hepatoprotection by Microalgae

3.1. Antioxidative Defense, Mitochondrial Protection, and Redox Signaling

Microalgal metabolites enhance hepatic antioxidant capacity and safeguard mitochondrial function—two central mechanisms in both acute and chronic liver injury. Carotenoids such as astaxanthin and fucoxanthin directly scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), stabilize membranes, boost endogenous antioxidants (e.g., SOD, CAT, GSH), and preserve mitochondrial function in hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [22,23,25,41,42,43,44,56]. Fucoxanthin activates cytoprotective pathways, including PI3K/AKT–Nrf2 and AMPK/Nrf2, leading to HO-1 induction and enhanced redox homeostasis in toxin- and lipotoxicity-induced models [43,45]. Astaxanthin mitigates mitochondrial overactivation linked to HSC activation, thereby reducing oxidative stress and profibrotic signaling [22,41,42].

Polysaccharides also contribute to redox regulation. Fucoidan raises hepatic glutathione levels, induces Nrf2/HO-1 signaling, and limits lipid peroxidation across multiple injury models, including alcohol-, ischemia–reperfusion-, and toxin-induced liver damage [35,36,40,47,50,61,66]. Paramylon (β-1,3-D-glucan) from E. gracilis reduces oxidative damage in acute and NASH models and upregulates SIRT1, linking redox regulation to metabolic homeostasis [18,19,21,46,62]. Similarly, phycocyanin (and phycocyanin-rich Spirulina) reduces oxidative stress and support mitochondrial function in radiation-, drug-, and toxin-induced liver injury models [37,70,74,76].

Of particular interest is the role of mitochondrial quality control. Fucoidan improves mitochondrial homeostasis and enhances mitophagy, particularly via the PINK1/Parkin axis, in models of alcoholic liver injury [40]. Together, carotenoids (via Nrf2 activation and mitochondrial stabilization) and polysaccharides/phycobiliproteins (via Nrf2–SIRT1 signaling and glutathione support) act in concert to suppress oxidative cascades that drive hepatocyte injury and HSC activation [18,22,23,25,35,37,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,70].

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Actions

Microalgal compounds exhibit broad immunomodulatory effects by suppressing hepatic inflammation through inhibition of NF-κB and TLR signaling and subsequent cytokine production (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), while also modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses. Fucoxanthin downregulates TLR4–NF-κB signaling in models of free fatty acid exposure and high-fat diet, thereby reducing hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress [45]. Fucoidan suppresses sterile inflammation in ischemia–reperfusion and toxin-induced models through a combination of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, including Nrf2–HO-1 activation and improved mitochondrial quality control [35,36,40,47,61].

Microalgal actives engage discrete immune nodes that are central to hepatic inflammation. In innate sensing, phycobiliprotein C-phycocyanin from Arthrospira attenuates TLR4–MyD88–NF-κB signaling in Kupffer cells and reduces COX-2/iNOS expression and p65 nuclear translocation, aligning with decreases in hepatic ROS and transaminases [82]. β-1,3-glucan (paramylon) from Euglena gracilis interacts with Dectin-1 and TLR2/4, biasing macrophage polarization toward M2 and dampening NLRP3 inflammasome activation; chemical modification that tunes particle size/assembly further enhances anti-fibrotic readouts. Among carotenoids, astaxanthin (from Haematococcus lacustris) stabilizes mitochondrial redox tone, suppresses NLRP3 and JAK/STAT-Th17 axes, and improves inflammatory histology in toxin-induced models [83]. Fucoxanthin (diatoms) down-modulates TLR4/NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages, consistent with hepatoprotective effects. In lipid mediators, marine EPA/DHA give rise to SPMs (resolvins, protectins, maresins) that signal via ALX/FPR2, ERV1/ChemR23, GPR32 to resolve inflammation, while GPR120/FFAR4 activation on Kupffer cells triggers β-arrestin-2–TAK1 inhibition, converging on NF-κB down-regulation. Together, these interactions mechanistically explain improvements across ALT/AST, cytokines, and fibrosis-linked endpoints summarized in our evidence tables.

Arthrospira and its active component phycocyanin attenuate inflammation in various liver injury models, including NASH, cisplatin, CCl4, and acetaminophen-induced damage, often via reduced NF-κB activity and restored redox balance [38,73,74,76,77,84]. Laminarin (β-1,3/1,6-glucan) reduces alcohol-induced hepatic inflammation in vivo [68].

Collectively, these findings support microalgae as multi-target immunomodulators capable of interrupting inflammation-driven progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis [35,36,40,45,47,61,68,73,74,76,77].

3.3. Reprogramming of Lipid Metabolism and Insulin Sensitivity

Correcting lipid dysregulation is a hallmark of microalgal intervention in metabolic liver disease. n-3 long-chain PUFAs (EPA and DHA), particularly those derived from Nannochloropsis and P. tricornutum, engage PPARα and AMPK signaling, promote mitochondrial β-oxidation, and suppress lipogenesis through downregulation of the SREBP-1c–ACC–FAS axis. These effects lead to reductions in hepatic triglyceride accumulation and improvements in insulin sensitivity in NAFLD and high-fat diet (HFD) models [20,24,25,26,80].

Additional in vivo and nutritional studies using microalgal oils or extracts—those from D. salina and Nannochloropsis—further support improvements in hepatic lipid handling and antioxidant capacity [24,33]. Carotenoids provide complementary metabolic effects: fucoxanthin improves serum lipid profiles and hepatic steatosis, and when co-administered with low-molecular-weight fucoidan, demonstrates synergistic efficacy in rescuing HFD-induced metabolic syndrome [45,50,57]. Spirulina’s impact on gut–liver axis modulation adds another layer, suggesting that improvements in lipid metabolism may also be mediated through microbial and immune interactions [85].

Overall, microalgal lipids and their complementary metabolites converge on key metabolic regulators—including AMPK and PPAR networks—to interrupt lipotoxic cascades and metabolic inflammation drive progression from NAFLD to NASH [24,26,33,45,50,57,85].

3.4. Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis

Several microalgal interventions restore gut-barrier integrity, reshape the gut microbiota, and modulate bile acid signaling, thereby mitigating endotoxemia and hepatic inflammation. For example, co-administration of fucoidan and galactooligosaccharides improves high-fat diet (HFD)-induced NAFLD by influencing both microbial composition and bile acid metabolism [61]. E. gracilis, through its β-1,3-glucan paramylon, acts as a next-generation prebiotic—enhancing Lactobacillus abundance and boosting intestinal antioxidant reserves—thereby linking its activity to immune–metabolic cross-talk along the gut–liver axis [3,17,19,62].

Similarly, ethanol extracts of Isochrysis zhangjiangensis alleviate alcohol-induced liver injury while correcting dysbiosis, and Caulerpa lentillifera has shown microbiota-mediated protection in ethanol-related models [51,81]. Broader reviews support the concept that macro- and microalgal components hold prebiotic potential for reducing inflammation-associated metabolic diseases [86,87]. Furthermore, low-molecular-weight polysaccharides from Chlorella have demonstrated gut–liver metabolic benefits in rodent models [88].

Microalgal interventions restore barrier integrity and rebalance gut ecology through complementary routes. Barrier: phycobiliprotein C-phycocyanin and algal polysaccharides upregulate tight-junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1) and mucin (MUC2), lowering endotoxemia (LPS) and downstream TLR4–NF-κB activation in the liver [82,83]. Microbiota: β-1,3-glucan (paramylon) from E. gracilis enriches SCFA-producing taxa (e.g., Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus), increases butyrate/propionate, and reduces pathobionts (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae), which, together with shifts in the bile acid pool toward FXR/TGR5 agonism, improves hepatic lipid and inflammatory readouts. These mechanisms mechanistically explain the observed reductions in cytokines and ALT/AST reported across models.

Taken together, these findings underscore the gut microbiota as a key therapeutic target through which microalgal compounds exert hepatoprotective effects [3,17,19,51,61,62,81,86,87,88].

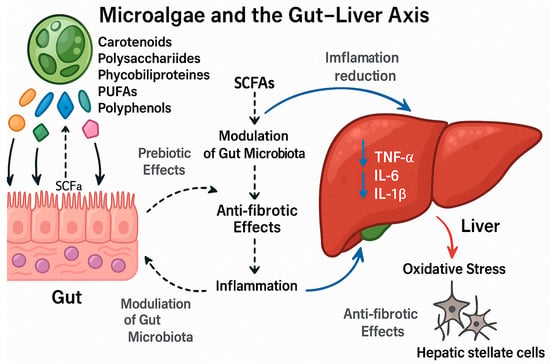

Key gut–liver signaling mechanisms modulated by microalgae are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The mechanisms of microalgae-derived bioactives in modulating the gut–liver axis. The diagram illustrates how microalgal bioactive compounds (carotenoids, polysaccharides, phycobiliproteins, PUFAs, and phenolics) exert hepatoprotective effects by targeting the gut–liver axis through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Colored symbols to the left denote major classes of microalgal bioactives: orange = carotenoids; green = polysaccharides/β-glucans (e.g., paramylon, fucoidan, laminarin); blue = phycobiliproteins (e.g., phycocyanin); teal = long-chain ome-ga-3 fatty acids (EPA/DHA); magenta = phenolic/phlorotannin-rich compounds. Solid black arrows indicate direction of flow or direct effects; dashed arrows indicate indirect, microbiota-mediated effects (e.g., production/signaling of short-chain fatty acids, SCFAs). Blue arrows mark beneficial hepatic outcomes: (i) reduction of hepatic inflammation driven by gut-derived signals/SCFAs; and (ii) anti-fibrotic actions on hepatic stellate cells. The downward blue arrows next to “TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β” indicate decreased cytokine levels. The red arrow labeled “Oxidative stress” denotes the pathological pressure that is counteracted by microalgal interventions.

- Prebiotic Action & Microbiota Modulation: Upon ingestion, these compounds act as prebiotics, promoting the growth of beneficial gut bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus) and increasing the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate.

- Intestinal Barrier Strengthening: SCFAs and certain microalgal compounds (e.g., paramylon) help strengthen the intestinal barrier by promoting the expression of tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, occludin), thereby reducing intestinal permeability and preventing the translocation of harmful microbial products, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), into the portal circulation.

- Attenuation of Liver Inflammation: Reduced gut-derived endotoxins (e.g., LPS) lead to decreased activation of Kupffer cells (liver macrophages) via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. This results in lower production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (↓TNF-α, ↓IL-6, ↓IL-1β) in the liver.

- Anti-fibrotic Effects: The consequent reduction in hepatic inflammation and direct actions of bioactives (e.g., astaxanthin, fucoidan) inhibit the activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), the primary drivers of liver fibrosis. This leads to decreased deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as collagen.

In summary, microalgal interventions break the vicious cycle of gut dysbiosis, impaired barrier function, and chronic liver inflammation, thereby ameliorating liver injury and fibrosis. Representative references: [3,17,19,51,61,62,81,86,87,88].

3.5. Anti-Fibrotic Mechanisms and Tumor-Preventive Signals

Microalgal bioactives interrupt fibrogenic progression by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation, extracellular matrix deposition, and associated profibrotic signaling pathways. Among carotenoids, astaxanthin reduces mitochondrial hyperactivation during HSC activation, while fucoxanthin reprograms HSC energy metabolism. Comparative analyses highlight broad anti-fibrotic activity across carotenoid types [22,41,42,44,89].

n-3 PUFAs reverse TGF-β1-induced fibrogenic gene expression by relieving PPARγ suppression in HSCs [26]. Paramylon—including its nanofiber forms—downregulates collagen I and α-SMA expression and mitigates fibrosis in both CCl4 and NASH models, and modulates MMPs and inflammatory drivers of fibrogenesis [19,21,64]. For fucoidan, animal studies consistently show reduced collagen accumulation and improved fibrotic markers under toxic and ischemic conditions [35,36].

Additionally, a diatom-derived peptide pair (NIPP-1/2) from Navicula incerta suppress TGF-β1-induced HSC activation, lowering both α-SMA and type I collagen expression—pointing to a novel, peptide-mediated anti-fibrotic mechanism [90].

Long-term and chemopreventive effects have also been documented: Arthrospira demonstrates protective actions against liver toxicity and carcinogenesis through persistent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, while carotenoid-rich Dunaliella preparations reduce fibrosis and hepatic injury In Vivo [32,33,56,76]. Because several of these bioactives (e.g., fucoxanthin, EPA/DHA) activate AMPK and PPAR pathways (see Section 3.3), metabolic reprogramming likely contributes to fibrosis attenuation. Further elucidation of upstream regulators and downstream fibrogenic targets is warranted to strengthen translational prospects [20,24,25,26,45,50,57,80].

3.6. Integrated Stress and Cell Death Programs: ER Stress/UPR, Ferroptosis, and Inflammasome Activation

Beyond redox and inflammatory modulation, microalgal compounds influence liver outcomes by engaging integrated stress responses and regulated cell- death pathways. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR)—via PERK–eIF2α–ATF4–CHOP, IRE1α–XBP1, and ATF6 signaling—govern in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and cell survival. Sustained or excessive UPR contributes to steatosis, inflammation, and cell death, whereas adaptive UPR signaling may exert cytoprotective effects [91,92,93].

Microalgal interventions that reduce oxidative and inflammatory stress (Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4 and Section 2.5) improve proteostasis markers, suggesting they may rebalance UPR dynamics—for example, through lowering CHOP/BiP expression and restoring antioxidant defenses.

Ferroptosis—an iron-dependent, lipid-peroxidation–driven form of regulated cell death—is governed by GPX4 and ACSL4 together with FSP1/CoQ10 pathways. In liver disease, ferroptosis plays a context-dependent, dual role: inhibiting ferroptosis protects hepatocytes in I/R, NAFLD, ALD, and DILI, whereas inducing ferroptosis in activated HSCs or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells can enhance therapeutic outcomes [94,95,96]. Because ferroptosis hinges on lipid peroxidation, its chemistry aligns with the antioxidant actions of microalgal carotenoids and phenolics (Section 2.1 and Section 2.5) and with EPA/DHA–driven membrane-lipid remodeling (Section 2.4), supporting the use of algal compounds to fine-tune ferroptotic susceptibility.

Lastly, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome—an inflammatory sensor responsive to mitochondrial ROS, ion flux, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)—drives caspase-1 activation and subsequent IL-1β/IL-18 maturation, contributing to liver inflammation and fibrosis. Microalgal compounds such as fucoidan, phycocyanin (Spirulina), and n-3 PUFAs appear to suppress NLRP3 activation indirectly by restoring redox and mitochondrial balance and inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB signaling [24,25,35,36,38,47,61,74,76,77]. A consolidated evidence grid of models, exposures and outcomes is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of preclinical and in vitro evidence supporting hepatoprotective effects. An upward arrow indicates an increase in substance concentration, while a downward arrow indicates a decrease in substance concentration.

4. Standardization, Quality, Safety, and Translational Bottlenecks

4.1. Variability in Composition and the Need for Standardization

Microalgal products exhibit significant compositional variability due to differences in species, strains, culture conditions (light, nutrient supply, salinity), harvest timing, and downstream processing such as drying, extraction, fractionation. Foundational reviews on microalgae as functional food ingredients emphasize that such variability affects in vivo dose–response relationships and reproducibility, highlighting the need for standardized cultivation practices and robust analytical controls—such as chemical fingerprints for carotenoids, phycobiliprotein purity, or defined sulfate/monosaccharide profiles for polysaccharides [1,2,3].

Further supporting this, fractionation and nutritional studies demonstrate that different extraction processes produce distinct bioactivity outcomes, making batch specifications and validated profiling essential for both research and product development [24,25,56]. Edible algal products used in functional foods also illustrate how standardized manufacturing and compositional consistency enhance translational reliability for liver-related metabolic endpoints [57].

Microalgal bioactivity is tightly coupled to chemodiversity shaped by genetics, cultivation, and processing. At the species/strain level, carotenoid profiles differ—e.g., H. lacustris accumulates mostly mono/di-esterified astaxanthin, whereas other microalgae yield higher free astaxanthin; esterification state alters stability, absorption, and downstream antioxidant/anti-fibrotic effects relevant to liver injury [11,12,83]. Culture conditions (light spectrum/intensity, nitrogen limitation, salinity/temperature, dissolved O2) reprogram lipid and pigment metabolism: EPA in Nannochloropsis rises under N-stress/high light. Downstream processing also matters: the purity and chromophore integrity of C-phycocyanin modulate ROS-scavenging and NF-κB inhibition, while particle size/assembly of Euglena β-1,3-glucan (paramylon) nanofibers tunes Dectin-1/TLR signaling and anti-fibrotic readouts.

4.2. Bioavailability, Formulation, and Pharmacokinetic Considerations

A central translational challenge for many microalgal bioactives is their inherently variable and often limited bioavailability, which directly impacts the dose needed to elicit therapeutic effects.

Microalgal bioactives differ substantially in their physicochemical characteristics: carotenoids are lipophilic and prone to oxidative degradation; phycobiliproteins are water-soluble but sensitive to processing; and polysaccharides vary in size, solubility, and sulfation patterns. Reviews in food science and microalgal biotechnology highlight several formulation levers—such as lipid-based emulsions for carotenoids, purification standards for phycocyanin, and molecular-weight control for fucoidan or laminarin—to improve stability, delivery, and uptake [1,2].

Studies using carotenoid extracts from Phaeodactylum and PUFA-rich fractions from Nannochloropsis confirm that the delivery matrix and co-nutrient environment affect both hepatic and systemic responses, arguing for formulation-aware study designs when investigating liver effects [24,25]. Moreover, historical comparisons of carotenoids underscore the role of isomeric composition and matrix interactions in modulating efficacy, emphasizing the need to report detailed composition alongside bioactivity data [56].

4.3. Safety, Toxicology, and Quality Assurance

Safety considerations for microalgal bioactives are highly matrix- and compound-dependent. While blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) have shown benefits in modulating NAFLD risk factors, rigorous source verification and testing for contaminants (e.g., cyanotoxins, heavy metals) remain essential [77]. Toxicological and disease-model studies using Arthrospira have consistently shown hepatoprotective effects—with improvements in liver enzymes and histology across cisplatin-induced toxicity, NASH, and other models—supporting a favorable hepatic safety profile under controlled sourcing [38,70,74,76,97].

Similarly, edible algae-derived products and phenolic-rich extracts display positive safety and efficacy signals in vivo, reinforcing the importance of standardized manufacturing for translational reliability [57,98]. Broader assessments of functional-food ingredients underscore the need for systematic toxicological evaluation, interaction studies, and upper-intake level definitions—especially as microalgal compounds transition from preclinical research to functional or therapeutic applications [1,2,3].

4.4. Regulatory and Clinical Translation Gaps

Key translational barriers include (i) material heterogeneity (Section 4.1), (ii) few well-powered clinical trials using composition-defined microalgal preparations, and (iii) inconsistent regulatory frameworks across countries for food, supplement, and therapeutic categories. This regulatory fragmentation presents a significant hurdle for developers. The path to approval varies drastically depending on whether a microalgal product is classified as a food, supplement, or drug. Generating the comprehensive safety, stability, and efficacy data required for regulatory filings—particularly for novel microalgal entities—demands substantial investment and poses a major translational barrier that must be proactively addressed. Reviews of functional ingredients and microalgae in food systems note that harmonized controls (HACCP, ISO) standards—and clearly defined identity–potency specifications are prerequisites for credible liver health claims [1,2,3].

Despite strong preclinical signals across carotenoids, phycobiliproteins, polysaccharides, and PUFAs, high-quality human studies remain rare. The field requires randomized, placebo-controlled trials with verified formulations and endpoints such as ALT, AST, imaging markers, and fibrosis scores [24,37,57].

4.5. Data-Driven Discovery: Multi-Omics, AI/ML, and Prioritization Pipelines

Emerging perspectives promote the integration of multi-omics platforms such as genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomic with machine learning to map strain–metabolite relationships, identify high-value chemotypes, and optimize production workflows for consistent output [4]. AI-assisted applications in microalgae—including strain detection, classification, and utilization—offer new tools for scale-up, process control, and quality assurance [52].

Moreover, domain-specific reviews on algae for metabolic disorders provide curated biological targets—oxidative, inflammatory, and metabolic pathways—that align with the mechanistic modules outlined in Section 3. These frameworks enable rational candidate selection for liver-focused applications [3,86].

4.6. Manufacturing Scale-Up and Sustainability

To enable cost-effective, reproducible deployment at scale, microalgal manufacturing must integrate robust strain preservation, controlled cultivation environments (e.g., photobioreactors), and standardized downstream processing. Industry-focused overviews recommend systems approaches that combine omics data with machine-learning–guided analytics to stabilize quality while also meeting sustainability metrics such as carbon footprint and resource efficiency [2,4].

Such platforms are essential for scaling up production of hepatoprotective microalgal ingredients—ensuring reliable supply for both nutraceutical and functional-food applications.

Furthermore, a critical hurdle is the scalability of production itself. Translating laboratory successes to industrial-scale manufacturing while maintaining strict control over bioactive potency and compositional consistency is non-trivial. Factors such as light gradation, nutrient heterogeneity, and contamination risk are magnified in large-scale bioreactors, potentially leading to batch-to-batch variation that can compromise reproducibility in clinical studies and commercial products.

A summary of key translational challenges and corresponding mitigation strategies is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key clinical translation challenges and proposed strategies.

5. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

5.1. Synthetic Biology for Strain Improvement

Advances in multi-omics and data-informed bioprocess engineering are reshaping how microalgal strains are selected and optimized for hepatoprotective applications. Integrated genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—coupled with machine learning—enable the mapping of strain genetics and culture conditions to the production of bioactives such as carotenoids, polysaccharides, phycobiliproteins, and n-3 PUFAs [2,4,54]. These tools support rational enhancement of mechanistic pathways already implicated in liver protection, including Nrf2 activation and AMPK/PPAR signaling. For instance, composition-tailored combinations like fucoxanthin and low-molecular-weight fucoidan have shown synergistic efficacy in models of diet-induced metabolic syndrome [50].

For multi-omics-guided strain selection, we propose a DBTL pipeline: (Design) build a strain × condition matrix prioritizing diversity in light spectrum, N/P, salinity, and temperature; (Build) generate long-read genomes/pangenomes and RNA-seq/WGCNA modules for target pathways (oxidative stress, lipid remodeling, bile acid signaling), with matched proteomics and untargeted/targeted metabolomics (lipidome, carotenoids, phycobiliproteins, β-glucans); (Test) quantify liver-relevant phenotypes (ALT/AST in cell/animal models, Nrf2/NF-κB readouts, bile acid profiles, SCFAs); (Learn) fit surrogate models (gradient boosting/Bayesian optimization) to rank strain–condition pairs, using multi-objective optimization (maximize efficacy; constrain growth, cost, safety). Feature attribution (e.g., SHAP) highlights driver modules/compounds; promising hits pass confirmatory DOEs and stability/scale checks. Optionally, integrate genome-scale models with measured flux surrogates to nominate edits (overexpression/knock-outs) before the next DBTL cycle. This makes the “omics → candidate → validation” path explicit and reproducible.

As predictive strain optimization and process control become routine, the consistency and potency of food-grade microalgal ingredients—oils, pigments, and polysaccharide-rich fractions—should improve, facilitating applications in translational nutrition and liver health interventions [1,2,24].

5.2. AI and Machine Learning in Bioactive Discovery

Artificial intelligence (AI) including machine learning (ML) is emerging as the powerful accelerator in natural product discovery and microalgal biotechnology. On the discovery side, ML-based models prioritize candidate compounds and extract fractions for hepatoprotective screening, improving throughput and reducing reliance on empirical testing [4,52,106]. In cultivation and downstream processing, AI is being used for phenotyping, real-time monitoring, and optimization—bringing stability to yields and bioactivity profiles [4,52,54,107].

Linking computational prioritization with experimental validation creates a feedback loop that accelerates and refines development of microalgae-derived interventions for liver health.

5.3. Potential Synergistic Combinations of Microalgal Bioactives

Given the orthogonal mechanisms across our modules (M1–M5), rational combinations may outperform single agents. Examples include paramylon (Euglena gracilis; Dectin-1/TLR2/4; gut barrier/innate bias) with astaxanthin (Haematococcus; mitochondrial redox/NLRP3) to couple barrier/immune training with ROS control [83]; C-phycocyanin (Spirulina; TLR4–NF-κB) with EPA/DHA (SPM generation; GPR120/FFAR4 signaling) to combine signal dampening with pro-resolution [82]. A pragmatic testing workflow uses fixed-ratio matrices at ED20–ED50, analyzed by Bliss independence/Chou–Talalay Combination Index (CI < 1 denotes synergy), with confirmatory ZIP scores and factorial DOE for formulation variables (carrier, esterified vs. free carotenoids, phycocyanin purity). Primary readouts: ALT/AST, hepatic TG, Nrf2/NF-κB/NLRP3 markers, HSC activation, gut TJ proteins and SCFAs. Safety/quality controls include peroxide values for LC-n3 oils and contaminant testing. This framework prioritizes combinations that are mechanistically complementary, manufacturable, and translationally tractable for liver indications.

5.4. Formulation and Delivery-Oriented Design

The effectiveness of microalgal interventions depends not only on which bioactives are used but also on how they are delivered. Lipophilic compounds such as astaxanthin and fucoxanthin benefit from food-grade lipid carriers or emulsions, improving both stability and bioaccessibility. Appropriately formulated extracts from Phaeodactylum, Nannochloropsis, and Haematococcus show hepatoprotective effects in vitro and in vivo [1,2,24,25].

Paramylon, a β-1,3-glucan from Euglena gracilis, offers a multifunctional delivery matrix with prebiotic, immunomodulatory, and anti-fibrotic potential. Its co-formulation with carotenoids or PUFAs may support multi-pronged mechanisms targeting oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [21,45,64]. Similarly, combinations such as fucoxanthin plus low-molecular-weight fucoidan demonstrate enhanced efficacy in metabolic liver injury models [24,45,50,57].

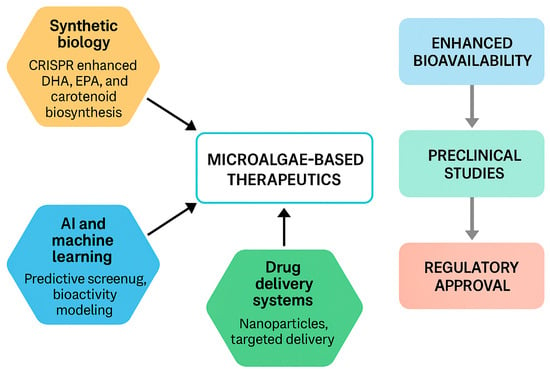

Figure 3 outlines an integrated pipeline from strain selection to clinical translation, emphasizing formulation as a key bridge.

Figure 3.

Translational pipeline for microalgae-based therapeutics. Upstream enablers—synthetic biology (strain/process engineering for carotenoids, EPA/DHA) and AI/ML for discovery & bioprocess control—feed into composition-defined ingredients. Formulation and delivery (e.g., lipid vehicles, micro/nano-encapsulation, and polysaccharide–carotenoid co-formulation) improve bioavailability, enabling robust preclinical efficacy and de-risking toward regulatory approval for foods/supplements/adjuncts. Representative references: [1,2,3,4,24,25,50,52,54,57].

5.5. Microbiome-Mediated Hepatic Effects

Given the pivotal role of the gut–liver axis, microalgal compounds with prebiotic properties are promising candidates for microbiota-driven hepatoprotection. E. gracilis and its paramylon fiber enrich beneficial Lactobacillus species and boost intestinal antioxidant levels—effects associated with reduced hepatic inflammation and improved metabolic function [17,19,62].

Combining microalgal components with traditional prebiotics—such as fucoidan and galactooligosaccharides—has been shown to shift bile acid profiles and microbiota composition in ways that attenuate NAFLD [61]. Extracts from Isochrysis zhangjiangensis have also corrected alcohol-related dysbiosis and liver injury [51]. These findings align with broader literature showing macro- and microalgae as viable prebiotics for controlling inflammation and metabolic disorders [86,87]. Looking ahead, synbiotic formulations (e.g., microalgae-derived prebiotics paired with tailored probiotics) could offer personalized strategies to support liver health [17,19,51,61,62,86,87].

5.6. Environmental Toxin Protection

Another important application area involves protecting the liver against environmental toxins and xenobiotics—including acetaminophen, alcohol, heavy metals, pesticides, and chemotherapeutic agents. Microalgal extracts—particularly those rich in fucoidan or carotenoids—consistently demonstrate hepatoprotective effects in such contexts by reducing oxidative stress, improving liver enzyme profiles, and preserving tissue architecture [35,36,38,40,47,48,51,78,84].

Protective signals extend to models of cisplatin and acrylamide toxicity, as well as classic CCl4-induced injury. Mechanistically, these benefits are commonly linked to activation of Nrf2–HO-1 pathways, mitochondrial quality control, and suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling. As a result, microalgae-derived compounds are being developed as candidate ingredients for functional foods or adjunct therapies in populations at risk of toxin-induced liver injury [21,34,40,55,64,73,74,75,97].

6. Conclusions

Microalgae provide a mechanistically diverse arsenal—carotenoids, phycobiliproteins, polysaccharides, and long-chain omega-3 lipids—that converge on oxidative stress control, inflammatory and innate immune modulation, lipid remodeling, gut–liver axis reinforcement, and anti-fibrotic pathways. Across cell and animal models, these actives consistently improve canonical liver outcomes, with early human data supporting translational potential in metabolic contexts.

Key limitations include heterogeneity in strain genetics, cultivation and processing conditions, variable standardization of extracts, and uneven study quality and endpoints. These issues complicate cross-study comparisons and dose–response generalization.

Future work should prioritize standardized materials and reporting, head-to-head comparisons of molecular forms and purity, and benchmarked in vivo models with harmonized endpoints. Multi-omics and AI-guided design–build–test–learn workflows can accelerate strain–condition selection and nominate combinations that are both mechanistically complementary and manufacturable. Well-designed clinical studies using validated non-invasive endpoints will be essential to define efficacy, safety, and dose ranges. Taken together, microalgal bioactives represent a credible, scalable, and clinically promising avenue for liver health that merits coordinated preclinical and clinical development. To realize the clinical potential of microalgal interventions, the field must now squarely address the key translational challenges highlighted herein: optimizing the bioavailability of diverse compound classes, ensuring the scalability of manufacturing processes, and navigating the complex regulatory hurdles for safety and efficacy approval.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and J.W.; methodology, G.S.; software, W.S.; validation, M.D., D.L. and J.W.; formal analysis, W.S.; investigation, W.S.; resources, D.L. and J.W.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; visualization, M.D. and G.S.; supervision, D.L. and J.W.; project administration, J.W.; funding acquisition, D.L. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by China’s National Key R&D Programs (2021YFA0910800) and The Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (CN) (ZR2022MC203).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| ACSL4 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| AIFM2 (FSP1) | apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 2 (ferroptosis suppressor protein 1) |

| ALD | alcoholic liver disease |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APAP | acetaminophen (paracetamol) |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| BA | bile acid |

| CAT | catalase |

| CCl4 | carbon tetrachloride |

| CHOP (DDIT3) | C/EBP homologous protein |

| CoQ10 | coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone-10) |

| C-PC | C-phycocyanin |

| CYP7A1 | cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| D-GalN | D-galactosamine |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| DILI | drug-induced liver injury |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| FAS | fatty acid synthase |

| FFA | free fatty acid |

| FGF15/19 | fibroblast growth factor 15/19 |

| FGFR4 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 |

| FSP1 (AIFM2) | ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 |

| FXR (NR1H4) | farnesoid X receptor |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| GLP | Good Laboratory Practice |

| GOS | galactooligosaccharide |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| GSH-Px (GPx) | glutathione peroxidase |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| HSC | hepatic stellate cell |

| IRE1α (ERN1) | inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha |

| IRI | ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| KLB (β-Klotho) | beta-Klotho |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| LX-2 | human hepatic stellate cell line LX-2 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| ML | machine learning |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| MW | molecular weight |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| Nrf2 (NFE2L2) | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PARK2 (Parkin) | E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 |

| PPARα | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| QC | quality control |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SREBP-1c | sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c |

| TAA | thioacetamide |

| TGF-β1 | transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| TGR5 (GPBAR1) | G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| UPR | unfolded protein response |

References

- Ampofo, J.; Abbey, L. Microalgae: Bioactive Composition, Health Benefits, Safety and Prospects as Potential High-Value Ingredients for the Functional Food Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporgno, M.P.; Mathys, A. Trends in Microalgae Incorporation Into Innovative Food Products with Potential Health Benefits. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chénais, B. Algae and Microalgae and Their Bioactive Molecules for Human Health. Molecules 2021, 26, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, M.; Elhalis, H.; Liu, Y.; Chow, Y.; Selvarajoo, K. Perspective: Multiomics and Machine Learning Help Unleash the Alternative Food Potential of Microalgae. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice No. 732: Docosahexaenoic Acid Oil Produced in Schizochytrium sp. 6 April 2018. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=732&sort=GRN_No&order=DESC&startrow=1&type=basic&search=732 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice No. 1156: Algal Oil (≥35% Docosahexaenoic Acid) from Schizochytrium sp. FJRK-SCH3. 8 February 2024. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=1156 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice No. 1185: Algal Oil (≥35% Docosahexaenoic Acid) from Schizochytrium sp. FJRK-SCH3. 14 March 2025. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=1185&sort=GRN_No&order=DESC&startrow=1&type=basic&search=1185 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice No. 1236: Algal Oil (≥40% Docosahexaenoic Acid) from Aurantiochytrium Limacinum H Sc-01. 10 June 2025. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=1236 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Allergies, Scientific Opinion on the extension of use for DHA and EPA-rich algal oil from Schizochytrium sp. as a Novel Food ingredient. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Ota, S. What is the correct name for the type of Haematococcus Flot. (Volvocales, Chlorophyceae)? Taxon 2016, 65, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of a change in specifications of the novel food oleoresin from Haematococcus pluvialis containing astaxanthin pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Kearney, J.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of astaxanthin for its use as a novel food in food supplements. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e05993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. 21 CFR 73.530—Spirulina Extract. 21 August 2015. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-73/subpart-A/section-73.530 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. 21 CFR Part 73—Listing of Color Additives Exempt from Certification. 22 March 1977. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-73 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Euglena Co., Ltd. Euglena for the Body That Focuses on Awakening the Body from the Ground up Proposes a New Approach to Health Habits. 16 March 2020. Available online: https://www.euglena.jp/en/news/20200316-2/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Qu, J.; Zhu, T.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Xia, Y.; Ke, X.; Fu, S.; Fan, B. Safety evaluation of Nannochloropsis gaditana oil as a novel food. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 162, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; He, J.; Chen, Z.; Qin, H.; Du, M.; Lei, A.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J. Euglena gracilis Promotes Lactobacillus Growth and Antioxidants Accumulation as a Potential Next-Generation Prebiotic. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 864565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S.; Yamanaka, C.; Koketsu, K.; Nishioka, M.; Onaka, N.; Nishida, N.; Takahashi, M. Effects of paramylon extracted from Euglena gracilis EOD-1 on parameters related to metabolic syndrome in diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, A.; Sugimoto, R.; Suzuki, K.; Shirakata, Y.; Hashiguchi, T.; Yoshida, C.; Nakano, Y. Anti-fibrotic activity of Euglena gracilis and paramylon in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, S.; Chaudhuri, D.; Ghate, N.B.; Mandal, N. Phytochemical profile of a microalgae Euglena tuba and its hepatoprotective effect against iron-induced liver damage in Swiss albino mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, A.; Suzuki, K.; Mitra, S.; Arashida, R.; Yoshida, E.; Nakano, R.; Yabuta, Y.; Takeuchi, T. Hepatoprotective effects of paramylon, a beta-1, 3-D-glucan isolated from Euglena gracilis Z, on acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009, 71, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Lee, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Shin, D.G.; Joshi, P.; Hong, S.H.; Alder, N.; Koo, S.I.; Lee, J.Y. Astaxanthin attenuates the increase in mitochondrial respiration during the activation of hepatic stellate cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 71, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Hou, Y.C.; Li, J.A.; Wang, J.F. The Role of Astaxanthin on Chronic Diseases. Crystals 2021, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.; García-Beltrán, A.; Kapravelou, G.; Mesas, C.; Cabeza, L.; Perazzoli, G.; Guarnizo, P.; Rodríguez-López, A.; Andrés Vallejo, R.; Galisteo, M.; et al. In Vivo Nutritional Assessment of the Microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana and Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Capacity of Its Functional Extracts. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, C.; Côme, M.; Blanckaert, V.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Faraloni, C.; Nazih, H.; Ouguerram, K.; Mimouni, V.; Chénais, B. Effect of Carotenoids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Treated HepG2 Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.Q.; Bae, M.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. n-3 PUFAs inhibit TGFβ1-induced profibrogenic gene expression by ameliorating the repression of PPARγ in hepatic stellate cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 85, 108452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepanlou, S.G.; Safiri, S.; Bisignano, C.; Ikuta, K.S.; Merat, S.; Saberifiroozi, M.; Poustchi, H.; Tsoi, D.; Colombara, D.V.; Abdoli, A.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Treatment for Patients with Liver Scarring Due to Fatty Liver Disease. 14 March 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-patients-liver-scarring-due-fatty-liver-disease (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- El-Baz, F.K.; Salama, A.; Salama, R.A.A. Therapeutic Effect of Dunaliella salina Microalgae on Thioacetamide- (TAA-) Induced Hepatic Liver Fibrosis in Rats: Role of TGF-β and MMP9. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7028314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, F.K.; Salama, A.A.A.; Hussein, R.A. Dunaliella salina microalgae oppose thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.E.B.; Aboulthana, W.M.; El-Feky, A.M.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Seif, M.M. Bio and phyto-chemical effect of Amphora coffeaeformis extract against hepatic injury induced by paracetamol in rats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Guo, C.Y.; Wu, J.Y. Fucoidan: Biological Activity in Liver Diseases. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 1617–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Ye, Q.F. Fucoidan reduces inflammatory response in a rat model of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, W.J.; Qin, S. Therapeutic effect of phycocyanin on acute liver oxidative damage caused by X-ray. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.F.; El-Sayed, A. Prospective Protective Effects of Arthrospira platensis Against Acetaminophen Induced Hepato-Renal Toxicity in Rats. Int. J. Morphol. 2023, 41, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Arceo, M.; Gómez-Zorita, S.; Aguirre, L.; Portillo, M.P. Effect of Microalgae and Macroalgae Extracts on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, M.L.; Zhang, H.Q.; Qiu, X.; Sun, Z.Y.; Liang, H. Protective effects of fucoidan against ethanol-induced liver injury through maintaining mitochondrial function and mitophagy balance in rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3842–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Kim, M.B.; Kang, H.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Comparison of Carotenoids for Their Antifibrogenic Effects in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Lipids 2019, 54, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, J.Y. Fucoxanthin Attenuates the Reprogramming of Energy Metabolism during the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Ammar, R.; Abu Zahra, H.; Abu Zahra, A.M.; Alfwuaires, M.; Alamer, S.A.; Metwally, A.M.; Althnaian, T.A.; Al-Ramadan, S.Y. Protective Effect of Fucoxanthin on Zearalenone-Induced Hepatic Damage through Nrf2 Mediated by PI3K/AKT Signaling. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kim, M.B.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Fucoxanthin metabolites exert anti-fibrogenic and antioxidant effects in hepatic stellate cells. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 6, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.N.; Zheng, J.W.; Tian, X.X.; Xu, B.G.; Yuan, F.L.; Wang, B.; Yang, Z.S.; Huang, F.F. Fucoxanthin Attenuates Free Fatty Acid-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Regulating Lipid Metabolism/Oxidative Stress/Inflammation via the AMPK/Nrf2/TLR4 Signaling Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ieiri, H.; Kameda, N.; Naito, J.; Kawano, T.; Nishida, N.; Takahashi, M.; Katakura, Y. Paramylon extracted from Euglena gracilis EOD-1 augmented the expression of SIRT1. Cytotechnology 2021, 73, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Abushouk, A.I.; Bahbah, E.I.; Bungau, S.G.; Alyousif, M.S.; Aleya, L.; Alkahtani, S. Fucoidan protects against subacute diazinon-induced oxidative damage in cardiac, hepatic, and renal tissues. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 11554–11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahgoub, H.A.; El-Adl, M.A.M.; Martyniuk, C.J. Fucoidan ameliorates acute and sub-chronic in vivo toxicity of the fungicide cholorothalonil in Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 245, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendran, H.R.B.; Sathivel, A.; Rekha, S. 12—Gastric and hepatic protective effects of algal components. In Functional Ingredients from Algae for Foods and Nutraceuticals; Domínguez, H., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 416–452. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Geng, L.H.; Zhang, Q.B.; Yue, Y. Co-activating the AMPK signaling axis by low molecular weight fucoidan LF2 and fucoxanthin improves the HFD-induced metabolic syndrome in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 94, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, L.; He, Y. Ethanol extracts of Isochrysis zhanjiangensis alleviate acute alcoholic liver injury and modulate intestinal bacteria dysbiosis in mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 4354–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Li, R.; Zhou, T. Machine learning for microalgae detection and utilization. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 947394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Álvarez-González, I.; Sumaya-Martínez, M.T.; Gutiérrez-Salinas, J.; Bautista, M.; Morales-González, Á.; García-Luna y González-Rubio, M.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L.; Morales-González, J.A. Review of natural products with hepatoprotective effects. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 14787–14804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamoglu, E. Artificial Intelligence and/or Machine Learning Algorithms in Microalgae Bioprocesses. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanitha, A.; Murthy, K.N.; Kumar, V.; Sakthivelu, G.; Veigas, J.M.; Saibaba, P.; Ravishankar, G.A. Effect of the carotenoid-producing alga, Dunaliella bardawil, on CCl4-induced toxicity in rats. Int. J. Toxicol. 2007, 26, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K.N.; Rajesha, J.; Swamy, M.M.; Ravishankar, G.A. Comparative evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of carotenoids of microalgae. J. Med. Food 2005, 8, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, K.; Inoue, N.; Tsuge, K.; Oikawa, A.; Kayashima, T.; Yanagita, T. Dried and Fermented Powders of Edible Algae (Neopyropia yezoensis) Attenuate Hepatic Steatosis in Obese Mice. Molecules 2022, 27, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekanov, K. Diversity and Distribution of Carotenogenic Algae in Europe: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sevilla, J.M.; Acién Fernández, F.G.; Molina Grima, E. Biotechnological production of lutein and its applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-M.; Liu, H.-J.; Zhang, X.-W.; Chen, F. Production of biomass and lutein by Chlorella protothecoides at various glucose concentrations in heterotrophic cultures. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, P.Y.; Fan, S.J.; Huang, J.L.; Yu, S.Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Li, H.J. Fucoidan and galactooligosaccharides ameliorate high-fat diet-induced dyslipidemia in rats by modulating the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Nutrition 2019, 65, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L.; Wang, J. Paramylon from Euglena gracilis Prevents Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Liver Injury. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 797096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S.; Yamanaka, C.; Mio, K. Microarray analysis of paramylon, isolated from Euglena gracilis EOD-1, and its effects on lipid metabolism in the ileum and liver in diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmic, C.; Barsanti, L.; Di Lascio, N.; Faita, F.; Evangelista, V.; Gualtieri, P. Anti-fibrotic effect of paramylon nanofibers from the WZSL mutant of Euglena gracilis on liver damage induced by CCl4 in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, Y.; Isoo, N.; Nakashima, A.; Suzuki, K.; Yamano, M.; Nariyama, T.; Yagame, M.; Matsui, K. Renoprotective effects of paramylon, a β-1, 3-D-Glucan isolated from Euglena gracilis Z in a rodent model of chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aysin, N.; Mert, H.; Mert, N.; Irak, K. The effect of fucoidan on the changes of some biochemical parameters and protein electrophoresis in hepatotoxicity induced by carbontetrachloride in rats. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2018, 52, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova-Shumkovska, J.; Krstanoski, L.; Veenman, L. Potential Beneficial Actions of Fucoidan in Brain and Liver Injury, Disease, and Intoxication-Potential Implication of Sirtuins. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.Y.; Zhu, L.F.; Zhou, Y.P.; Han, S.; Cao, Y.Y.; Hu, Z.M.; Luo, Y.; Bao, L.Y.; Wu, X.X.; Qin, D.D.; et al. Laminarin ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage and its molecular mechanism in mice. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Haas, W.; Crosas, B.; Santamaria, P.G.; Gygi, S.P.; Walz, T.; Finley, D. The HEAT repeat protein Blm10 regulates the yeast proteasome by capping the core particle. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]