Abstract

This study assesses the ecological conditions of the Colentina urban river system by investigating phytoplankton community traits, with a focus on resource use efficiency (RUE) as a functional indicator. Using phytoplankton biomass, taxonomic composition, and RUE, we assessed the ecological effects of anthropogenic pressures. Our results showed that total phosphorus values indicated chronic eutrophication conditions but supported increased phytoplankton biomass, especially in spring and summer. RUE varied independently of biomass, with maximum values recorded in autumn, suggesting a functional recovery phase, characterized by higher RUE under nutrient decline. The analysis at the phytoplankton group level highlighted distinct ecological strategies: cyanobacteria presented a high RUE in autumn, diatoms increased their efficiency during nutrient limitation periods, and green algae showed a functional flexibility throughout the study period. In contrast, spatial analyses indicated a decoupling between biomass and RUE, reflecting the influence of local environmental conditions on ecosystem functioning. RUE was significantly influenced by total phosphorus, nitrogen forms, temperature and light availability. Our results strengthen the combined approach of structural (biomass) and functional (RUE) indicators for the assessment of communities and anthropogenic impacts in urban and peri-urban aquatic ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Urban aquatic ecosystems are increasingly subject to intense anthropogenic pressures through habitat fragmentation and pollution, including nutrient enrichment from multiple sources. Rivers that cross cities due to adverse conditions often become hotspots of environmental degradation, reflecting cumulative impacts along their course [1,2,3,4]. Multiple anthropogenic pressures compromise the structure and functioning of ecosystems, affecting their capacity to provide ecological services [5]. From both points, water bodies present in urban areas are considered vulnerable. In addition, these systems are frequently used for flood control, water storage, and other services, which contribute to the emergence of complex ecological gradients influenced by local hydrological features [6]. The cumulative impact of high nutrient inputs, other compounds, hydrological regime, fragmentation, etc., has significant effects on the ecological functioning of these systems [7].

Phytoplankton is a key component of these aquatic ecosystems and an important indicator of their ecological status. As the base of the aquatic food web, communities respond rapidly to environmental changes, which makes them valuable for assessing ecosystem responses and the anthropogenic impact [8,9]. Recent literature provides a detailed perspective on the relationship between phytoplankton diversity and the functionality of urban ecosystems exposed to anthropogenic impacts. In this context, assessing resource use efficiency at the phytoplankton level represents a valuable tool for identifying imbalances in the functioning of aquatic ecosystems [10,11]. Recent ecological approaches emphasize the importance of Resource Use Efficiency (RUE)—the ability of organisms to convert available resources into biomass—as a more nuanced indicator of ecosystem productivity [10,12]. RUE is defined as the ratio between biomass produced and the concentration of available nutrients, reflecting the capacity of communities to transform resources into biological production. In this context, RUE serves not only as a metric of phytoplankton performance but also as an indirect indicator of the resilience and metabolic efficiency of aquatic ecosystems under stress [13].

Eutrophication alters the structure of phytoplankton communities, reducing RUE and disrupting energy transfer to higher trophic levels [14,15,16]. Biodiversity loss threatens the health and productivity of aquatic ecosystems. Conversely, higher diversity increases RUE and provides multiple services, and this relationship varies over space and time, being influenced by environmental factors [17,18]. Therefore, the phytoplankton diversity, biomass, and functional traits integrate the effects of environmental conditions as well as disturbance factors [19]. The Colentina River system, a succession of interconnected lakes in the Bucharest metropolitan area (Romania), represents a suitable model to explore how urbanization shapes nutrient dynamics, phytoplankton structure, and Resource Use Efficiency as functional ecosystem responses [20,21]. Under the conditions of multiple synergistic anthropogenic pressures (fragmentation, eutrophication, and other sources of diffuse pollution) on the Colentina urban river, evaluating the functional efficiency of phytoplankton communities in accessing available nutrients may represent an effective approach to identifying the ecosystem’s functioning.

In the context of high anthropogenic pressures on urban aquatic ecosystems, the assessment of RUE at the level of the main phytoplankton communities can provide a functional perspective on the ecological conditions. RUE is the ratio between the phytoplankton biomass and the concentration of available nutrients, reflecting the capacity of communities to transform resources into biological production. In our study, we measured RUE to assess ecosystem functionality, its capacity to convert available resources into biomass, providing a direct measure of its performance. The present study aims to analyze the ecological conditions of the Colentina lake system in Bucharest by investigating the seasonal and spatial dynamics of phytoplankton biomass and RUE, with a focus on the ecological strategies of the main taxonomic groups: Chlorophyceae, Bacillariophyceae and Cyanobacteria. The analysis focuses on the seasonal and spatial dynamics of nutrient availability and phytoplankton biomass, as well as the response of the main phytoplankton groups to environmental variations. Our study objectives were to quantify the seasonal and spatial variations in phytoplankton biomass (chlorophyll a) in relation to the environmental gradient; to assess RUE as an indicator of ecosystem productivity along the Colentina urban lakes system; and to establish the contribution of the main phytoplankton and RUE groups (Chlorophyceae, Bacillariophyceae, Cyanobacteria) to identify their ecological strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

Bucharest is crossed by two rivers, the Colentina and the Dambovita. Starting in 1933, due to the need to manage urban waters, both rivers were subjected to hydrotechnical works that required regularization and integration into a modern urban infrastructure. The Colentina became a priority due to the expansion of the city, public health issues, and the need for economic development. Its transformation consisted of hydrotechnical works with the creation of a lake chain with control locks, bank stabilization and wetland drainage of the ponds. Thus, the Colentina River was integrated into a hydrosocial system that simultaneously fulfilled social and technical functions: on the one hand, it supported urban development through lakes and recreational areas for Bucharest; on the other hand, it was designed as a key component of water management, ensuring drinking water supply, sewage and rainwater drainage, as well as irrigation for the agricultural lands surrounding the city. Today, the Colentina River includes 15 anthropogenic chain lakes, with an important role in managing rainwater and maintaining an urban ecological balance. Many of the areas through which the river passes suffer from pollution, and the banks are subject to constant urban pressures [22,23].

The diversity of local influences and hydromorphological features along the Colentina River provides a relevant framework for analyzing the impact of natural and anthropogenic factors on the aquatic environment.

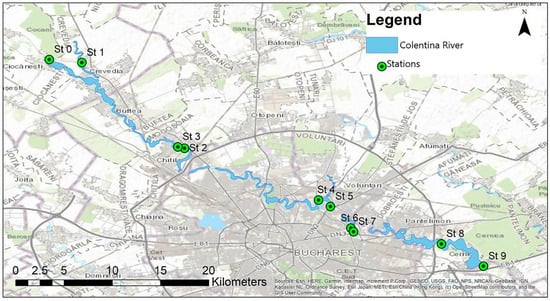

The study was conducted along the Colentina River, with monthly in situ measurements carried out between March and November 2019. Sampling locations included an unaltered natural sector of the Colentina River (Station 0), the Crevedia area (Station 1) with natural traits, peri-urban Lake Mogoșoaia (Stations 2 and 3), urban Lake Plumbuita (Stations 4 and 5), urban Lake Fundeni (Stations 6 and 7), peri-urban Lake Cernica (Station 8), and Cernica canal (Station 9) (Figure 1). The monitoring stations were established to capture anthropogenic gradients of local (rural, peri-urban, and urban influences) and were located at varying distances along the Colentina River. Given the length of the river and the features of the lakes, some stations were situated in proximity. These peri-urban stations reflect cumulative local influences and were used for comparative analyses with stations characterized by rural and urban influences, which are located farther apart.

Figure 1.

Study site and sampling points.

2.2. Physicochemical Parameters

A Hanna Instruments HI 9828 multi-parameter probe (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) was used for water column measurements of percentage saturation of DO (%), temperature (°C), oxidation–reduction potential (ORP) (mV), pH, and turbidity (FTU). Light intensity was assessed with a Lutron LX-1102 light meter (Lutron Electronics Co., Inc., Coopersburg, PA, USA). Water depth was determined using a Secchi disk, and water flow (m/s) was measured with a Geopacks flowmeter (Geopacks Instrumentation, India).

For nutrient analysis, the samples were collected from the water column in plastic bottles. Samples were maintained in cold conditions for laboratory analysis. A 200 mL aliquot was filtered through GF/F Whatman filters (65 μm diameter; Cytiva, Whatman, MA, USA). Nutrients were determined spectrophotometrically following a modified Berthelot method for N–NH4 (mg N–NH4 L−1) [24], Tartari and Mosello [25] for N-NO3 (mg N–NO3 L−1), P-PO4 (mg P-PO4 L−1), and TP (mg PL−1).

Physicochemical parameters were used in the GLM analysis as quantitative explanatory variables influencing the phytoplankton group-level resource use efficiency.

2.3. Phytoplankton Sampling and Analysis

Phytoplankton samples were collected from the water column using a Patalas–Schindler plankton trap (4 L), stored in 500 mL containers, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. The samples were left to settle for 2 weeks and were subsequently analyzed under an inverted microscope (Axiovert 40C, Zeiss, Germany) according to the Utermöhl method [26]. Taxonomic identification was carried out using identification keys specific to Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) [27,28,29,30], Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) [31,32], and Chlorophyceae (green algae) [33,34]. Organisms were identified to the genus or species level, as appropriate. Together with taxonomic assessments, phytoplankton density was estimated and expressed in cells L−1. Phytoplankton biomass was evaluated in situ using a BBE-Moldaenke FluoroProbe (BBE Moldaenke GmbH, Kiel, Germany), which enables quantification of chlorophyll a concentration as a proxy for total biomass, as well as differentiated estimates for the three principal phytoplankton groups: Chlorophyceae, Cyanobacteria, and Bacillariophyceae. Biomass values were expressed in μgL−1 of chlorophyll a [35].

2.4. Phytoplankton Diversity Analysis

The taxonomic diversity of the phytoplankton community was evaluated using the following indices:

S—Species richness, expressed as the total number of species identified per sample.

H′—Shannon–Wiener diversity index, calculated according to the formula:

where pᵢ represents the proportion of the i species within the sample.

H′ = Σpi ln(pi)

J′—Evenness index (Pielou’s index), computed using the formula:

where S = species richness [36].

J = H′/ln S

2.5. Resource Use Efficiency of Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton RUE was employed to quantify the ratio between the biomass produced and the concentration of available nutrients, following the model proposed by Ptacnik et al. [10]. In the Colentina urban river system, phosphorus has been consistently identified as the main limiting nutrient, as confirmed by our results and previous studies [37]. Therefore, total phosphorus (TP) was used as the denominator in the definition of RUE. This formula provides a measure of the efficiency of the phytoplankton community per unit TP, regarded as the primary limiting nutrient in freshwater ecosystems [38].

In this study, RUE was calculated as the ratio between phytoplankton biomass, expressed by chlorophyll a concentration, and total phosphorus (TP):

To assess the resource use efficiency (RUE) within the phytoplankton community, RUE values were calculated both for the total phytoplankton biomass (Total con. µgL−1) and separately for the main taxonomic groups (Chlorophyceae, Bacillariophyceae, and Cyanobacteria). This approach allowed the identification of functional variations specific to each algal group, as well as the comparison of ecological efficiency between taxonomic groups under different environmental conditions.

- RUE—resource use efficiency of total phytoplankton biomass.

- RUEBac—resource use efficiency of Bacillariophyceae.

- RUEChl—resource use efficiency of Chlorophyceae.

- RUECyan—resource use efficiency of Cyanobacteria.

2.6. Data Processing

2.6.1. Two-Way ANOVA

We conducted a two-way ANOVA analysis with interactions to assess the temporal and spatial dynamics of phytoplankton biomass and resource use efficiency. The two fixed factors—ecosystem type (with multiple sampling sites) and season (spring, summer, autumn)—were applied separately to each ecological variable, and the interaction effects between them were measured. Statistical significance was determined using F-statistics and corresponding p-values, with a threshold of p < 0.05 considered statistically significant [39].

2.6.2. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

Redundancy Analysis (RDA) is widely used in ecological and phytoplankton community studies to relate explanatory variables to biological response variables. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) is a multivariate statistical technique that extends multiple linear regression to model the linear relationships between a set of explanatory variables (X) and a set of response variables (Y). In our study, RDA was applied to assess how seasonal variation in phytoplankton group-level biomass (X) influenced RUE at the group level (Y)

2.6.3. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC)

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) was applied to evaluate the spatial similarity of resource use efficiency and phytoplankton biomass. The dissimilarity between samples was quantified using Euclidean distance. Clusters were formed using Ward’s method, an agglomeration technique [40]. The method allowed the identification of spatial patterns and groupings in RUE and phytoplankton biomass, facilitating ecological interpretation of their spatial heterogeneity.

2.6.4. GLM (Generalized Linear Model)

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to analyze the relationship between RUE at the phytoplankton group level as a quantitative response variable Y and multiple explanatory variables X, namely diversity indices and physicochemical parameters (light intensity, depth, turbidity, temperature, pH, water flow, dissolved oxygen (DO%), redox potential (ORP), ammonium (NH4), nitrate (NO3), and total phosphorus (TP)). The use of GLMs facilitates the understanding of the environmental factors influencing RUE. GLMs extend traditional linear regression by allowing the response variable to follow non-normal distributions and thus adjust for the data often encountered in ecological datasets [41].

In statistical analysis, data were preprocessed by logarithmic (ln) transformations to ensure a normal distribution. Analyses were performed using XLStat 2013 [41,42] and Past4.16c [43].

3. Results

3.1. Total Phosphorus as a Key Driver in RUE Assessment

Total phosphorus (TP) showed significant seasonal differences (F2,85 = 245.05; p < 0.0001), with high levels in spring (min–max = 0.05–1.52 mg PL−1; mean = 1.05 mg PL−1) and summer (min–max = 0.08–1.05 mg PL−1; mean = 0.93 mg PL−1). In spring, the TP levels exceeded the threshold, indicating hypertrophic conditions and persisted into summer, although with a gradual decrease toward autumn (min–max = 0.03–0.25 mg PL−1; mean = 0.10 mg PL−1). From a spatial perspective, elevated phosphorus values were consistently observed in all the lakes of the Colentina River system, suggesting multiple sources and accumulation of nutrients along its course. High values of nutrients were recorded in the upstream lakes Colentina (0.61 mg PL−1), Crevedia (0.69 mg PL−1), and Mogoșoaia (0.71 mg PL−1), indicating pressure from peri-urban areas. Further increases in Plumbuita, Fundeni (0.74 mg PL−1), and Cernica canal (0.74 mg PL−1) also highlight the impact of anthropogenic activities on nutrient enrichment.

3.2. Phytoplankton Biomass (Chl-a)

Phytoplankton biomass showed a clear seasonal pattern with an overall increase from spring to summer, followed by a decrease in autumn (Table 1). Spring values ranged from min–max = 7.58 to 125.20 μgL−1 (mean = 60.08 μgL−1), followed by an increase in summer to a wider range of min–max = 3.91–105.24 μgL−1 (mean = 72.12 μgL−1). Then, in autumn, the range was min–max = 1.72–108.90 μgL−1, with a mean of 54.74 μgL−1 (Table 1). The phytoplankton dynamics reflect varying responses of taxa, ranging from low development of some to episodic algal blooms of others.

Table 1.

The mean (± SD), median, minimum, and maximum of phytoplankton biomass µgL−1.

In terms of spatial distribution, except for the upstream natural Colentina area (mean = 10.22 μgL−1), all other lakes recorded significantly higher biomass levels (Table 1). High values were found in Lake Mogoșoaia (mean = 79.31 μgL−1) and Lake Fundeni (mean = 74.92 μgL−1), indicating blooming conditions. Instead, Lake Crevedia showed a moderate impact (mean = 69.25 μgL−1). Downstream, the last sampling points, Lake Cernica and Cernica canal, exhibited comparable values (60.34 μgL−1 and 62.58 μgL−1), suggesting a slight attenuation of biomass accumulation.

3.3. Seasonal and Spatial Phytoplankton Diversity and Functional Implications

Diversity indices represented a valuable tool for assessing spatiotemporal changes in phytoplankton community structure and offered a deeper insight into the ecological processes driven by the structural shifts. Summer was defined by the highest species richness (S), Shannon diversity index (H′), and Pielou’s evenness (J), indicating favorable conditions for a diverse community (Table 2).

Table 2.

Colentina Lakes’ diversity indices of phytoplankton communities.

Spring and autumn exhibited lower diversity values and higher variability, indicating community instability and dominance by a few opportunistic taxa. For example, Lake Plumbuita showed extremely low diversity in spring (H′ = 0.13, J = 0.05), corresponding to an algal community dominated by a single taxon.

3.4. Resource Use Efficiency

3.4.1. Seasonal Traits of RUE

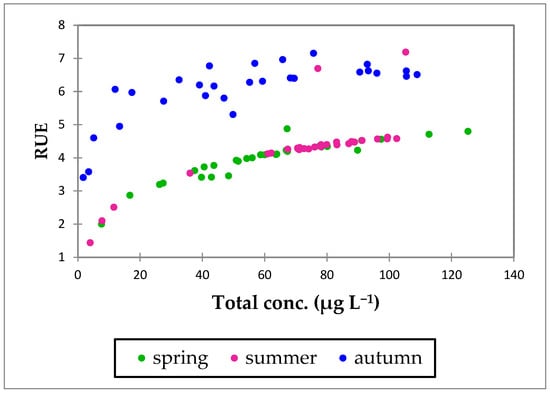

During the study period, the investigated aquatic ecosystems were characterized by eutrophic conditions, with elevated phosphorus concentrations and high phytoplankton biomass accumulation. The Resource Use Efficiency displayed a marked seasonal pattern (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The seasonal variation in phytoplankton RUE across biomass dynamics.

In spring and summer, RUE values remained relatively low and homogenous across ecosystems (mean = 3.94 in spring, 4.29 in summer). In autumn, RUE increased considerably (mean = 6.06) (Table 3; Figure 2), displaying the most resource-efficient period, even with low biomass levels.

Table 3.

The seasonal means of resource use efficiency and phytoplankton group biomass.

At the group level, Chlorophyceae showed distinct seasonal patterns in biomass accumulation and resource use efficiency. In spring, green algae dominated the early stages of phytoplankton development, reaching moderate biomass (mean = 28.18 µgL−1) with relatively low RUE (range = −1.86 to 4.05; mean = 2.96) (Table 3). During summer, biomass increased (mean = 38.22 µgL−1), coupled with slightly improved RUE (min–max = 0.03 to 6.51; mean = 3.50). In autumn, Chlorophyceae biomass decreased (mean = 28.03 µgL−1) with a high variability and the highest seasonal RUE (mean = 4.94).

Bacillariophyceae biomass peaked in spring (mean = 11.06 μgL−1), followed by a decline in summer (mean = 8.49 μgL−1) and autumn (mean = 5.93 μgL−1). Noteworthy, the seasonal dynamics in RUE followed an inverse trend, were low (mean = 1.78) in spring and summer (mean = 1.77), and considerably increased in autumn (mean = 3.20) (Table 3).

Also, Cyanobacteria exhibited a distinct decoupling between biomass production and RUE. During spring, both biomass (mean = 3.49 μgL−1) and RUE (mean = 0.88) were lowest, with occasional negative RUE values. In summer, cyanobacterial biomass increased significantly (mean = 13.90 μgL−1), with moderate RUE values (mean = 2.63). In autumn, cyanobacterial biomass decreased (mean = 8.88 μgL−1), while RUE reached its highest seasonal average (mean = 4.37).

Overall, the ANOVA results (Table 4) showed statistically significant effects of the main factors (lake and season) on the phytoplankton biomass, as well as on their associated RUE (Table 4). The strongest responses were recorded for Cyanobacteria RUE (R2 = 0.76; F17,70 = 13.35; p < 0.0001) and total phytoplankton biomass RUE (R2 = 0.77; F17,70 = 13.44; p < 0.0001). Green algae were distinguished by a high selectivity in ecosystem type, both in terms of biomass (F5,70 = 8.54; p < 0.0001) and their efficiency (F5,70 = 6.08; p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

The two-way ANOVA (2 factors: ecosystem and season) results for phytoplankton group biomass (µg L−1) and RUE. The table presents the coefficient of determination (R2), F-statistics with associated p-values for each variable tested, and the effects of two independent categorical variables on each single quantitative dependent variable, testing three hypotheses: the main effect of the first variable, the main effect of the second variable, and their interaction effect.

Seasonality also had a significant effect on phytoplankton, especially for cyanobacteria biomass (F2,70 = 17.24; p < 0.0001) and RUE (F2,70 = 78.05; p < 0.0001). The interaction between lake and season was significant only for total phytoplankton biomass (F10,70 = 2.85; p = 0.00) and RUE (F10,70 = 2.43; p = 0.02).

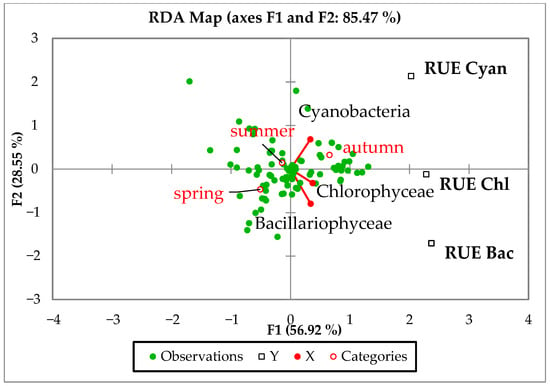

Redundancy analysis (RDA) reveals stronger seasonal differentiation among phytoplankton groups, which influence community efficiency and productivity through their functional traits (Figure 3). The biplot shows a proximity of the vectors for green algae and diatoms, suggesting an overlap of ecological niches. In contrast, the blue-green vector emphasizes a negative relationship with diatoms, underlining the functional differences in RUE strategies and environmental preferences. Cyanobacteria also showed a distinctive, strong positive correlation between biomass and RUE, particularly in autumn. Chlorophyceae also exhibited a positive association between biomass and RUE across seasons, while Bacillariophyceae displayed low RUE values, despite higher biomass (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

RDA biplot with the relationship between the RUE and biomass of plankton groups along the study seasons.

3.4.2. Spatial Traits of RUE

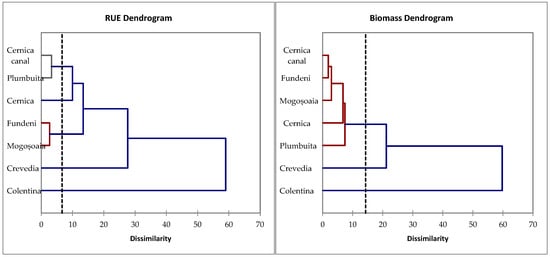

The spatial distribution of both phytoplankton biomass and resource use efficiency, assessed by hierarchical cluster dendrograms (Figure 4), provides insights into productivity patterns and regulatory mechanisms (RUE) with effects on ecosystem functionality. The biomass dendrogram grouped the Cernica canal, Fundeni, and Mogoșoaia lakes into a single cluster, reflecting similarity in phytoplankton assimilation patterns. In contrast, the RUE dendrogram revealed a different functional grouping, with the Cernica canal being closely grouped with Plumbuita and Lake Cernica, thus indicating similarities in resource assimilation efficiency, despite differences in biomass magnitude. These contrasting cluster patterns highlight that RUE does not always align with biomass accumulation. On the other hand, both dendrograms separated the more natural upstream ecosystems, Colentina and Crevedia, from the urban lakes, thus highlighting their unique ecological status in terms of both biomass and nutrient use efficiency.

Figure 4.

Ecosystem dendrograms of RUE and phytoplankton biomass. Colors indicate the clusters, and the dashed line marks the dissimilarity threshold.

3.4.3. Environmental Drivers of Resource Use Efficiency

A generalized linear model (GLM) was applied to identify the key environmental drivers that influenced the Resource Use Efficiency of phytoplankton (Table 5). The model indicated that species richness, Shannon index, and evenness significantly contributed to explaining the variation in RUE. The seasonal differences in diversity patterns were significantly associated with RUE. Through Generalized Linear Models (GLM) (Table 5), Shannon’s H’ and evenness J were established as significant predictors of RUE dynamics, indicating that higher diversity and even distribution of communities tend to use efficiently the available resources. This supports that biodiversity enhances ecosystem functioning by favoring complementary resource use among taxa.

Table 5.

Generalized linear model (GLM) summary statistics between RUE of phytoplankton groups and measured environmental factors, diversity indices.

Among the abiotic factors, total phosphorus (TP), nitrate (NO3−), and ammonium (NH4+) (F = 25.92, p < 0.0001) significantly influenced the RUE, underscoring the dependence on the nutrient availability of the phytoplankton productivity (Table 5). Other physicochemical variables, as pH (F = 74.81, p < 0.0001) and light availability (F = 42.18, p < 0.0001), were also significant predictors of primary production processes. Temperature showed a strong influence on Cyanobacteria RUE (F = 24.89, p < 0.0001), which highlights that the thermal regime in urban lakes favored their development. Additionally, turbidity and dissolved oxygen showed significant effects on both total biomass and cyanobacteria.

4. Discussion

Our results showed that high nutrient availability did not consistently translate into high resource use efficiency. Instead, RUE was characterized by a seasonal decoupling of biomass, with autumn appearing as the period with the highest efficiency, even when phytoplankton was lower. This pattern suggests that phytoplankton groups adopted different ecological strategies: green algae and cyanobacteria increased their efficiency when nutrients were low, while diatoms maintained a low RUE under conditions of high nutrient availability but improved under conditions of nutrient limitation. On the other hand, the contrast of the strategies employed shows us the functional diversity of phytoplankton responses to urban eutrophic conditions and how seasonal dynamics shape community resource use. By integrating RUE as an indicator of phytoplankton biomass patterns and taxonomic structure under different ecological conditions, we provided information on community functions, especially during different periods and in water bodies marked by nutrient enrichment or potential ecological disturbances. RUE, along with phytoplankton biomass assessment, offers additional insight into how efficiently communities convert available nutrients, capturing subtle shifts in the ecosystem. This indicator has been used in studies to identify how ecosystems respond to both chronic and episodic nutrient enrichment [44,45].

In Colentina ecosystems, high concentrations of total phosphorus, particularly in spring and summer, reflect chronic eutrophication throughout the Colentina river–lake system, with significant urban and peri-urban nutrient inputs. These nutrient-rich conditions supported elevated phytoplankton biomass, especially in peri-urban and urban lakes (Table 1), and revealed altered ecological functioning. Elevated nutrient content, particularly phosphorus, is widely reported to lead to an increase in phytoplankton biomass in aquatic ecosystems affected by urban and agricultural runoff. Similar studies have shown that chronic nutrient eutrophication leads to prolonged high phytoplankton biomass in spring and summer [46,47,48]. Further analysis of the total phytoplankton biomass combined with resource use efficiency revealed clear seasonal and spatial patterns that reflect the functional responses of urban river ecosystems and the extent of human impact.

Our results revealed a pronounced seasonal variability in RUE (Figure 2), especially in autumn when, despite moderate phytoplankton biomass, RUE was high, indicating that communities were able to optimize nutrient uptake after the peak of stress and productivity in summer. This autumn peak may result from a functional recovery phase after the collapse of the algal bloom, which, in combination with low phosphorus levels, together enhance the efficiency of nutrient assimilation [49]. In contrast, lower RUE in spring and summer suggests inefficient phosphorus use, potentially driven by unfavorable environmental conditions or competitive dominance of certain species [50,51]. Similar patterns were reported by Zang et al. [52], who linked seasonal inefficiencies in nutrient use to bloom episodes and environmental factors such as light and temperature. These findings reinforce the idea that high nutrient availability does not automatically lead to strong resource efficiency, thus highlighting the importance of seasonal dynamics in regulating phytoplankton nutrient uptake. The phosphorus, albeit essential, does not alone determine changes in phytoplankton communities or RUE patterns. Changes in phytoplankton composition can lead to simultaneous increases in biomass and RUE after a seasonal transition from summer to autumn, which may reflect an adaptation of nutrient uptake strategies during post-stress periods, even under resource-limited conditions [45,53]. Thus, our study highlights that autumn may represent a critical ecological phase of functional recovery, characterized by increased nutritional efficiency within phytoplankton communities.

At the group level, Chlorophyceae, Bacillariophyceae, and Cyanobacteria exhibited distinct seasonal patterns in biomass and RUE (Table 3; Figure 3), reflecting distinctive adaptive ecological strategies. Cyanobacteria showed significant seasonal variability in resource use efficiency, with a clear decoupling from biomass (Table 3). Spring recorded the lowest biomass (6.39 µgL−1) and RUE (0.88) (including negative RUE values in some urban ecosystems), indicating inefficient resource use. Summer was characterized by the highest biomass (13.90 µgL−1), with moderate RUE (2.63), associated with the frequent occurrence of algal blooms. In contrast, in autumn, although biomass decreased (8.88 µgL−1), RUE reached its maximum value (4.37), highlighting an adaptive response to maximize uptake under conditions of low nutrient availability. These results indicate that cyanobacteria adjust their physiological strategies according to seasonal environmental conditions, reflecting a high fitness and competitiveness in stressed urban ecosystems. The cyanobacteria’s survival strategies include mechanisms such as atmospheric nitrogen fixation and access to limited forms of phosphorus, giving them a competitive advantage over other phytoplanktonic groups [12,54]. According to Olli et al. [55], during diazotrophic cyanobacteria blooms, the species contribute to increasing the phosphorus use efficiency, contributing to the persistence of the community. Also, studies have shown that cyanobacteria can “anticipate seasonal changes”, triggering adaptive mechanisms that optimize resource use depending on availability [56,57,58]. The significant values of the coefficient of determination (R2) for the RUE of cyanobacteria seasonal differences (Table 4) confirm their sensitivity to environmental factors and their ecological relevance in the context of urbanization and eutrophication. Instead, Bacillariophyceae biomass peaked in spring (11.06 µgL−1), associated with low RUE (1.78), suggesting rapid biomass accumulation without efficient phosphorus uptake. While biomass was decreasing until autumn, their RUE increased under nutrient-limited conditions, pointing to a seasonal switch toward more efficient uptake strategies. Diatoms tend to maximize the rapid biomass accumulation over optimization of phosphorus uptake, suggesting that phosphorus was not a limiting factor [59]. In contrast, under autumn conditions, biomass declined significantly (5.93 µgL−1), while RUE increased (3.20), indicating a group strategic physiological shift toward more efficient nutrient utilization. In response to nutrient limitation, diatoms enhance their ability to acquire phosphorus and adjust their carbon metabolism to reduce dependence on phosphorus, redirecting towards the accumulation of reserve compounds [60]. The ecological strategy through which diatoms maximize growth rates under abundant resource conditions and shift toward efficiency-driven survival strategies under scarcity is commonly encountered, which allows diatoms to dominate during nutrient enrichment and to maintain themselves under nutrient-limited conditions [61,62].

Chlorophyceae showed a different seasonal trend in which biomass and phosphorus use efficiency depended differently on environmental conditions. The communities maximized their biomass in summer, while phosphorus use efficiency increased gradually until autumn (Table 3). These traits have shown that green algae enhance resource use efficiency in communities, supporting ecosystem functioning across environmental gradients [50]. Analyzing only the biomass often overlooks important functional dynamics and ecological strategies. RUE reveals these aspects, as shown by the group-level patterns. Green algae are known for their ability to undergo physiological changes depending on nutrient availability [8,63]. On the other hand, the relationship between biomass and RUE reflects an important ecological strategy: under conditions of abundant nutrients, green algae grow rapidly but without a highly efficient use of phosphorus, whereas under limited conditions, they optimize resource use to survive [64]. Thus, the changes in autumn can be accounted for by the occurrence of isolated blooms followed by rapid declines, a phenomenon described in many studies investigating phytoplankton dynamics in urban systems [65].

Seasonality significantly influenced resource use efficiency for all phytoplankton groups (Table 4). The highest RUE values were recorded in autumn, especially for Cyanobacteria (F2,70 = 78.05; p < 0.0001), which may indicate a post-bloom functional reorganization and an increased capacity to utilize available phosphorus. This trend was also found in Chlorophyceae (F2,70 = 14.06; p < 0.0001) and Bacillariophyceae (F2,70 = 7.15; p < 0.0001), highlighting distinct seasonal adaptation strategies. In contrast, ecosystem types had a significant effect on total biomass (F5,70 = 18.53; p < 0.0001) and on the RUE of total phytoplankton biomass (F5,70 = 66.28; p < 0.0001), highlighting functional differences between urban lakes and natural areas. In particular, RUECyan was influenced by ecosystem type (F5,70 = 3.47; p = 0.01), suggesting that anthropogenic pressure favors opportunistic strategies of this group. Also, the interaction between season and ecosystem was significant for total biomass (F10,70 = 2.85; p = 0.00) and RUE (F10,70 = 2.43; p = 0.02), confirming that the functional response of phytoplankton is dependent on the local context and temporal dynamics.

Seasonal resource availability can increase group-level competition, leading to the exclusion of less competitive taxa. This was reflected in the presence of biomass outliers and reduced diversity in some lakes (Table 2). Under stress conditions, some species undergo rapid growth and blooming, while others are suppressed. Responses to intergroup competition further illustrate niche differentiation: diatoms increased their RUE under low-nutrient conditions in autumn, while cyanobacteria exploited the environmental conditions, and chlorophytes maintained a constant efficiency throughout the entire period. Understanding these interactions is crucial for interpreting the decoupling between biomass efficiency and predicting ecological trends in response to urban pressures [66,67,68]. The seasonal succession of phytoplankton groups was closely linked to diversity patterns and functional shifts. Spring was characterized by lower Shannon diversity (1.78) but high variation (SD = 0.70), reflecting dominance by a few r-strategists such as diatoms. The relatively low RUE during this period indicates inefficient resource conversion, likely due to competitive pressures or environmental instability. Summer was marked by bloom episodes but with higher diversity (2.19) and smaller variation (SD = 0.35), suggesting a more stable and balanced community.

Overall, environmental stressors in summer reduced growth efficiency despite occasional biomass peaks and favorable diversity (Figure 2). In autumn (Table 2), diversity was intermediate (Shannon–Weiner = 1.85), indicating an ecological transition, with all groups showing improved RUE. This phase could represent an adaptive shift where reduced competition and nutrient availability favor more efficient species and community arrangements. These seasonal phytoplankton patterns align with r/K selection theory: diatoms exhibit traits of K-strategists (stable biomass, lower efficiency), cyanobacteria behave as r-strategists (opportunistic, high RUE under stress), and green algae display intermediate traits, reflecting functional flexibility and resilience [69]. The seasonal succession of phytoplankton groups closely corresponds with changes in diversity and functional traits.

Spatial analyses (Figure 4) revealed a functional decoupling across sites. For instance, although the Cernica canal clustered with Fundeni and Mogoșoaia in terms of biomass, it grouped with Plumbuita and Lake Cernica based on RUE. This functional similarity across structurally distinct sites suggests that resource use is governed by specific local environmental conditions rather than phytoplankton biomass levels. Previous work has demonstrated that spatial variability in phytoplankton RUE often reflects heterogeneity in environmental conditions rather than phytoplankton biomass [50,70]. Additionally, natural upstream sectors (Colentina, Crevedia) consistently formed separate clusters in both biomass and RUE analyses, indicating favorable ecological conditions and lower urban impact. The consistent separation of the Colentina and Crevedia sections from the urban lakes indicates that the upstream natural areas, although presenting lower biomass, maintain a more balanced and efficient use of resources. This highlights the added value of RUE in revealing functional differences that are not captured by biomass alone. Also, the patterns align with the urbanization gradient along the Colentina River, where upstream natural and peri-urban sectors contrast with downstream urban lakes. Higher urban pressure (nutrient enrichment and hydromorphological alteration) is associated with increased biomass but lower efficiency, while upstream sites show moderate biomass and more efficient resource use. These findings echo results from urban gradient studies, where upstream sectors displayed higher functional diversity and RUE compared to downstream, more urbanized sites [71,72].

Phytoplankton biomass and RUE are both sensitive indicators of eutrophication and bloom dynamics, but RUE adds a functional layer, providing early insight into phytoplankton adaptive capacity and responses. Our data show that environmental variables, especially total phosphorus, nitrate, ammonium, light, and temperature, significantly influenced RUE (Table 5). Similar to our findings, studies in eutrophic lakes have demonstrated that environmental variables, such as phosphorus and nitrogen compounds, light availability, and temperature, significantly regulate phytoplankton RUE, underscoring its ecological importance [71]. The complementary perspectives of total phytoplankton as well as group-level analyses allow for the detection of critical ecological changes, such as community reorganization, resilience thresholds, or transitions to different ecological states. For example, Ye et al. [50] showed that RUE captures the efficiency of nutrient uptake and assimilation under fluctuating environmental stress, which is not necessarily reflected by biomass levels. Integrating structural indicators such as biomass with functional indicators such as RUE, along with data on diversity and environmental factors, provides a comprehensive framework for assessing ecosystem health. Numerous studies highlight the value of combining RUE to reveal nuanced ecological responses to anthropogenic pressures. Collectively, evidence supports the use of phytoplankton biomass and RUE as complementary indicators to improve the diagnosis and management of eutrophication and ecological degradation in aquatic networks [73,74]. Our findings support the use of phytoplankton biomass and RUE as integrated indicators for the diagnosis and management of anthropogenic impacts on anthropogenically impacted systems, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas.

Biomass provides a structural measure of productivity, while RUE captures how efficiently available resources are transformed into biomass. Our results showed that the two parameters did not vary in parallel, a relevant distinction for the assessment of urban ecosystems in our study, highlighting that a high level of biomass does not necessarily imply an efficient use of resources, and increased efficiency can occur even under conditions of moderate biomass. Therefore, the simultaneous use of the two indicators allowed us to identify functional differences that are not evident from the simple structural analysis of phytoplankton biomass. The low RUE values recorded during periods of stress (spring and summer) indicate that reducing nutrient pressures is essential for increasing functional efficiency. In contrast, high values in autumn suggest a recovery capacity; thus, RUE is not only a descriptive indicator but can also guide practical measures to reduce eutrophication and improve the resilience of urban ecosystems. Our study, using the phytoplankton biomass/phosphorus ratio as an index of resource use, confirms that TP was a limiting nutrient in the Colentina system, supporting the validity of this approach. However, in aquatic ecosystems, there may be periods of co-limitation due to nitrogen or light, which means that RUE based on TP should be interpreted as a dominant, but not exclusive, factor of phytoplankton functional efficiency. This does not make this approach vulnerable but only emphasizes that RUE complements, rather than replaces, other structural and functional indicators. Therefore, integrating RUE with phytoplankton biomass provides an operational framework for assessing and monitoring urban ecosystems as an early warning tool.

5. Conclusions

The assessment of phytoplankton communities along the Colentina River and the integration of RUE as a functional indicator led us to the following main conclusions of the study:

- Resource use efficiency represented a valuable tool in identifying key ecological aspects apart from the evaluation of phytoplankton biomass per se.

- The chronic eutrophication conditions that characterized the ecosystems of the Colentina River led to an increase in phytoplankton biomass, also indicating blooming periods. RUE showed that high phosphorus values did not always lead to increased resource use efficiency, thus signaling a functional imbalance in stress periods (spring and summer).

- Group-level analyses showed that phytoplankton exhibited distinct seasonal ecological strategies, reflecting their different adaptability:

Cyanobacteria presented a high RUE in autumn, suggesting a superior adaptive capacity under nutritional stress conditions.

Bacillariophyceae accumulated biomass rapidly in spring but with low efficiency, increasing RUE in autumn under nutritional limitation.

Chlorophyceae maintained a relatively constant RUE and showed functional flexibility.

- 4.

- Spatial analyses revealed a decoupling between RUE and biomass in different ecosystems of the Colentina system, highlighting that the functional state of the ecosystem is determined by local conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.M. and L.I.F.; methodology, M.M.M., L.I.F., R.D.C. and C.A.D.; formal analysis, L.I.F.; investigation, M.M.M., L.I.F., R.D.C. and C.A.D.; data curation, L.I.F.; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing, M.M.M., L.I.F. and R.D.C.; visualization, L.I.F.; supervision, M.M.M.; project administration, M.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project no. RO1567-IBB02/2025 of the Institute of Biology Bucharest of the Romanian Academy and RO1567-IBB06/2025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the referees for their valuable comments. Any additional individuals acknowledged have provided their consent to be mentioned.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Paul, M.J.; Meyer, J.L. Streams in the urban landscape. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, D.B.; Hartley, D.; Jackson, R. Forest cover, impervious-surface area, and the mitigation of stormwater impacts. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2002, 38, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.J.; Roy, A.H.; Feminella, J.W.; Cottingham, P.D.; Groffman, P.M.; Morgan, R.P. The urban stream syndrome: Current knowledge and the search for a cure. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2005, 24, 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Reidy, C.A.; Dynesius, M.; Revenga, C. Fragmentation and flow regulation of the world’s large river systems. Science 2005, 308, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.L.; Paul, M.J.; Taulbee, W.K. Impacts of urbanization on stream ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 333–365. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaljević, M.; Stević, F.; Krizmanić, J.; Savić, Ž.; Tokodi, N.; Dulić, T.; Marinović, Z. Phytoplankton functional groups as indicators of the ecological status of urban lakes. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 57, 454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Chislock, M.F.; Doster, E.; Zitomer, R.A.; Wilson, A.E. Eutrophication: Causes, consequences, and controls in aquatic ecosystems. Natl. Educ. Knowl. 2013, 4, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.S. The Ecology of Phytoplankton; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Padisák, J.; Crossetti, L.O.; Naselli-Flores, L. Use and misuse in the application of the phytoplankton functional classification: A critical review with updates. Hydrobiologia 2009, 621, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptacnik, R.; Solimini, A.G.; Andersen, T.; Tamminen, T.; Brettum, P.; Lepisto, L.; Willen, E.; Rekolainen, S. Diversity predicts stability and resource use efficiency in natural phytoplankton communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5134–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodapp, D.; Hillebrand, H.; Striebel, M. “Unifying” the concept of resource use efficiency in ecology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J. Biodiversity improves water quality through niche partitioning. Nature 2011, 472, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucak, T.; Trolle, D.; Andersen, H.E.; Refsgaard, J.C.; Thodsen, H.; Erdogan, S.H.; Ozen, A.; Beklioglu, M. Urbanization and nutrient enrichment drive changes in resource use efficiency and community structure of phytoplankton in urban lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 1370–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Abdullah Al, M.; Ndayishimiye, J.C.; Yang, J.R.; Isabwe, A.; Luo, A.; Yang, J. Urbanization reduces resource use efficiency of phytoplankton community by altering the environment and decreasing biodiversity. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 112, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, A.; Aris, A.Z.; Juahir, H.; Ramli, M.F.; Kura, N.U. River water quality assessment using environmentric techniques: Case study of Jakara River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 5630–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Cui, B. Eutrophication drives resource use efficiency variations in freshwater plankton communities across river–lake continuum in China’s Poyang Lake Basin. Hydrobiologia 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Duffy, J.E.; Zavaleta, E. The functions of biological diversity in an age of extinction. Science 2012, 336, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchman, E.; Klausmeier, C.A. Trait-based community ecology of phytoplankton. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, C.; Stanca, C.; Rîșnoveanu, G.; Cîmpeanu, S.M. Phytoplankton diversity and water quality assessment in urban lakes of Bucharest. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 22, 12517–12527. [Google Scholar]

- Stanca, C.; Rîșnoveanu, G.; Dinu, C.; Cîmpeanu, S.M. Resource use efficiency of phytoplankton in relation to environmental gradients in urban lakes. Hydrobiologia 2019, 831, 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, M.; Stoiculescu, R.C. Landscape changes in Colentina River basin (between Buftea and the confluence with Dâmbovița) as reflected in cartographic documents (1791–2000). Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Cotoi, C.; Iorga, A.; Păduraru, R.; Georgescu, A.I. The lives and afterlives of the Dâmbovița: Between ghost and living river. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2025, 8, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krom, M.D. Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia: A study of a modified Berthelot reaction using salicylate and dichloroisocyanurate. Analyst 1980, 105, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartari, G.; Mosello, R. Metodologie analitiche e controlli di qualità nel laboratorio chimico dell’Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia. In Documenta Dell’Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia; Verbania Pallanza: Verbania, Italy, 1997; Volume 60, pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Edler, L.; Elbrächter, M. The Utermöhl method for quantitative phytoplankton analysis. In Microscopic and Molecular Methods for Quantitative Phytoplankton Analysis; Karlson, B., Cusack, C., Bresnan, E., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Bacillariophyceae, Teil 2. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Bacillariophyceae, Teil 3. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Bacillariophyceae, Teil 4. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Naviculaceae I. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, Teil 1: Chroococcales. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Spektrum, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, Teil 2: Oscillatoriales. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Springer: Spektrum, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ettl, H. Chlorophyta I. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ettl, H.; Gärtner, G. Chlorophyta II. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine, A.; Escoffier, N.; Belhocine, A.; Nasri, A.B.; Hamlaoui, S.; Yéprémian, C.; Bernard, C.; Troussellier, M. On the use of the FluoroProbe(r), a phytoplankton quantification method based on fluorescence excitation spectra for large-scale surveys of lakes and reservoirs. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T. Paleontological Data Analysis; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Florescu, L.I.; Moldoveanu, M.M.; Catană, R.D.; Păceșilă, I.; Dumitrache, A.; Gavrilidis, A.A.; Iojă, C.I. Assessing the Effects of Phytoplankton Structure on Zooplankton Communities in Different Types of Urban Lakes. Diversity 2022, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Wang, H.; Na, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lu, X.; Fan, Y. Temperate urban wetland plankton community stability driven by environmental variables, biodiversity, and resource use efficiency: A case of Hulanhe Wetland. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1148580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)—Exploring possible interaction between factors. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2014, 39, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, I.; Ruske, S.; Topping, D.O.; Gallagher, M.W. Evaluation of hierarchical agglomerative cluster analysis methods for discrimination of primary biological aerosol. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 4979–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Addinsoft. XLSTAT Pro. Data Analysis and Statistical Solutions for Microsoft Excel; XLSTAT: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, M.; Smith, J.A.; Lee, K. Phytoplankton diversity enhances resource use efficiency through complementary nutrient uptake strategies under variable nutrient ratios. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptacnik, R.; Solimini, A.G.; Andersen, T.; Tamminen, T.; Brettum, P.; Lepistö, L.; Willén, E.; Rekolainen, S. Phytoplankton diversity predicts resource use efficiency across freshwater and brackish systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10854–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Cole, J.J.; Kitchell, J.F.; Pace, M.L. Impact of dissolved organic carbon, phosphorus, and grazing on phytoplankton biomass and production in experimental lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.M.; Roberson, J. Phytoplankton growth regulation by dissolved P and mortality regulation by endogenous cell death over 35 years of P control in a mountain lake. J. Plankton Res. 2021, 44, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, B.; Laws, E.A. Nutrients and phytoplankton in a shallow, hypereutrophic urban lake: Prospects for restoration. Water 2017, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.Y.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhong Tang, Y. Harmful algal blooms significantly reduce the resource use efficiency in a coastal plankton community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, F. Functional diversity promotes phytoplankton resource use efficiency. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E. Stoichiometric constraints on phytoplankton resource use efficiency in monocultures and mixtures. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. Groups and driving factors of cyanobacterial blooms in a subtropical reservoir. Water 2019, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, L.; Gall, A.; Hillebrand, H.; Striebel, M. Warming and oligotrophication cause shifts in freshwater phytoplankton communities. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 4532–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, R.; Forchhammer, K. Acclimation of unicellular cyanobacteria to macronutrient deficiency: Emergence of a complex network of cellular responses. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2503–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olli, K.; Klais, R.; Tamminen, T. Rehabilitating the cyanobacteria–niche partitioning, resource use efficiency and phytoplankton community structure during diazotrophic cyanobacterial blooms. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbur, M.L.; Bratton, B.P.; Johnson, C.H. Bacteria can anticipate the seasons: Photoperiodism in cyanobacteria. Science 2024, 385, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, M. The driving mechanism of phytoplankton resource utilization efficiency variation on the occurrence risk of cyanobacterial blooms. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Effects of phytoplankton diversity on resource use efficiency in a eutrophic urban river of Northern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1389220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembu, T.; Mühlroth, A.; Alipanah, L.; Bones, A.M. The effects of phosphorus limitation on carbon metabolism in diatoms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovio-Fragoso, J.P.; de Jesús-Campos, D.; López-Elías, J.A.; Medina-Juárez, L.Á.; Fimbres-Olivarría, D.; Hayano-Kanashiro, C. Biochemical and molecular aspects of phosphorus limitation in diatoms and their relationship with biomolecule accumulation. Biology 2021, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilmi, A.; Karjalainen, S.M.; Landeiro, V.L.; Heino, J. Freshwater diatoms as environmental indicators: Evaluating the effects of eutrophication using species morphology and biological indices. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, T.; Goutam, U.; Arya, A.; Gautam, S. Effect of nutrients on diatom growth: A review. Trends Sci. 2022, 19, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, B.J.; Van Mooy, B.A.; Cotner, J.B.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Trick, C.G. Phosphorus uptake and storage in phytoplankton: Mechanisms and ecological implications. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Litchman, E.; Klausmeier, C.A.; Schofield, O.M.; Falkowski, P.G. The role of functional traits and trade-offs in structuring phytoplankton communities: Scaling from cellular to ecosystem level. Ecol. Lett. 2007, 10, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, U.; Adrian, R.; Baigun, C.; Elser, J.J.; Gaedke, U.; Ibelings, B.; Jeppesen, E.; Lürling, M.; Molinero, J.C.; Mooij, W.M.; et al. Beyond the plankton ecology group (PEG) model: Mechanisms driving plankton succession. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2012, 43, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, G.E. The paradox of the plankton. Am. Nat. 1961, 95, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.L.S. The seasonal succession of optimal diatom traits. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2019, 64, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, B.J. Interspecific resource competition among nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 63, 736–750. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, I.M.; Williamson, T.J.; González, M.J.; Vanni, M.J. Nitrate, ammonium, and phosphorus drive seasonal nutrient limitation of chlorophytes, cyanobacteria, and diatoms in a hyper-eutrophic reservoir. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2019, 65, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, Å.; Li, L.; Sun, X. Water depth and land use intensity indirectly determine phytoplankton functional diversity and regulate resource use efficiency at a multi lake scale. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y. Urbanization reduces resource use efficiency of phytoplankton community by altering the environment and decreasing biodiversity. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhu, M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G. Spatiotemporal dependency of resource use efficiency on phytoplankton diversity in Lake Taihu. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzouki, E.; Cerco, C.; Winder, M.; Klais, R. Phytoplankton functional responses to eutrophication and warming in freshwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 63, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Functional trait diversity improves phytoplankton resource use efficiency in eutrophic lakes. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 109898. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).