Abstract

Postharvest operations are cost intensive in microalgae production, and when electrocoagulation–electroflotation (EC/EF) with aluminum anodes is used, aluminum can remain associated with biomass and wash streams; hence, a selective postwash process is needed. Accordingly, this study defined an operational window for aluminum desorption that preserves the energetic advantage of EC/EF. A response-surface design (I-optimal/CCD) was used to evaluate the effects of the EDTA concentration (1–100 mM), contact time (5–20 min), mixing speed (100–300 rpm), and pH (6–10) on EC/EF-harvested Chlorella sp. biomass, with ANOVA and model diagnostics supporting adequacy. EDTA concentration and mixing emerged as significant factors, whereas time and pH acted mainly through interactions; moreover, quadratic terms for EDTA and mixing indicated diminishing returns at high levels. Consequently, the surface predicted an optimum near EDTA ≈ 65 mM, time ≈ 20 min, pH 10, and 100 rpm, corresponding to ~97% aluminum removal. Importantly, a confirmation run under these conditions across eight chlorophyte strains consistently achieved >95% removal, revealing narrow dispersion yet statistically distinguishable means. Taken together, coupling EC/EF with an EDTA postwash operation in the identified window effectively limits aluminum carry-over in microalgal biomass and, therefore, provides a reproducible basis for downstream conditioning and potential recirculation within biorefinery schemes.

1. Introduction

The postharvest stage accounts for a decisive fraction of the operational and energy costs in microalgae production. Various analyses estimate that harvesting and dewatering alone represent approximately 20–30% of the total cost, with additional penalties associated with maintenance and the electrical demand of mechanical operations such as centrifugation, thereby conditioning the overall technoeconomic feasibility of the process [1,2]. Within this context, electrocoagulation coupled with electroflotation (EC/EF) has been proposed as a primary separation operation because of its ability to concentrate biomass in short residence times with competitive specific energy consumption, aligning separation intensity with more favorable cost windows [3]. Under representative conditions, recovery rates of ≈98% were documented within 15 min at 40.78 mA·cm−2 and an interelectrode distance of 0.5 cm, with a specific energy demand of ≈4.03 kWh·kg−1 of biomass. These metrics support its integration as a preconcentration or harvesting step within biorefineries [4]. Moreover, when EC is applied as a preconcentration stage prior to centrifugation, total energy consumption decreases to 0.136 kWh·kg−1 of dry biomass, confirming the potential of hybridization to lower operating expenses (OPEX) without sacrificing yield [5].

The system behavior is governed by coupled mechanisms: electrocoagulation generates hydroxylated metal species that neutralize the electric double layer and promote “sweep” flocculation, whereas electroflotation contributes to microbubbles that enhance particle–bubble collisions and accelerate floc rise. This coupling explains the high separation kinetics, provided that the current density, pH, and reactor geometry are properly controlled [3]. From the perspective of inorganic chemistry, aluminum speciation depends on pH and ligands: near-neutral ranges favor amorphous Al(OH)3 phases conducive to colloidal capture, whereas at alkaline pH, the fraction of aluminate Al(OH)4− increases, leading to higher dissolved aluminum concentrations and reduced retention efficiency. This underscores the need to control the pH both during harvesting and in subsequent washing steps [6].

The choice of electrode material directly affects the impurity profile of both solids and auxiliary streams. Comparative studies of EC/EF in microalgae harvesting have reported postprocess effluent concentrations of 1.34–9.09 mg·L−1 when sacrificial aluminum anodes are employed, which are incompatible with recirculation without selective posttreatment. This necessitates the design of desorption/chelation barriers to comply with regulated markets [7]. At the same time, continuous and pilot-scale studies have demonstrated that optimizing the current density, interelectrode spacing, and bubbling regimes results in high efficiencies at moderate specific energy demands, leaving room for postwashing operations without neutralizing the energy advantage of the EC/EF [8].

To assess the technological acceptability of aqueous streams in trains employing aluminum-based coagulants, multiple water treatment studies have adopted a residual aluminum concentration of 0.05–0.2 mg·L−1 as an operational benchmark. This range is explicitly used in residual control and coagulation optimization studies as an attainable performance criterion in full-scale plants [9,10]. Indeed, trials designed to minimize dissolved aluminum often set ≤0.2 mg·L−1 as the operational target and verify compliance as a function of pH and dose, thereby providing a reproducible metric to validate polishing and recirculation steps in integrated schemes [11]. On this basis, transferring such benchmarks as internal targets in biorefineries via EC/EF enables evidence-based decisions on whether a washing stream may be recycled for cultivation or requires additional treatment without relying on public health regulatory limits [10].

The postharvest section thus becomes a critical node for controlling the aluminum associated with the cell surface and limiting the dissolved fraction during washing. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is commonly adopted as a reference chelating agent because of the high stability of its complexes with trivalent cations. However, persistence and limited degradability have been noted in soils and aquatic systems, with half-lives extending at low concentrations and cases of no degradation at high concentrations, increasing the risk of organic–metal complex transport in open systems [12]. Consequently, agents with improved environmental profiles have been prioritized, particularly [S,S]-EDDS (ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid) and GLDA (glutamic acid diacetic acid), which maintain effective complexation with faster degradation under representative conditions. In highly contaminated soils, EDDSs exhibit half-lives of ~1.3–3.0 days and complete mineralization within weeks, which is in marked contrast with EDTA [13]. Similarly, soil-washing platforms have demonstrated the applicability of GLDA as a biodegradable chelant in recirculation systems, meeting “ready biodegradability” criteria under standardized frameworks [14]. Interpretation of these results relies on the hierarchy of OECD 301/310 series tests, which are widely employed by the scientific community to identify nonpersistent substances and establish comparability between agents [15]. Within this landscape it is useful to clarify why EDTA is prioritized at this stage so that the postwash optimization remains interpretable and comparable.

Notwithstanding its environmental persistence, EDTA remains a robust methodological reference to delimit the post-EC/EF desorption window. It forms high-stability complexes with trivalent cations and its speciation and stability constants are well parameterized in the neutral-to-alkaline range relevant to our postwash, which reduces uncertainty when interpreting complexation and liquid–solid mass-transfer responses [16]. Moreover, recent computational and experimental analyses and reviews of aminopolycarboxylates support this pH dependence and cross-metal consistency of EDTA performance [17]. In microalgae, EDTA washes are standardized to remove surface-adsorbed metals and to separate extra- and intracellular fractions, which consolidates its role as operational reference before testing greener substitutions [18]. In contrast, GLDA and S,S-EDDS offer better biodegradability yet often show lower stability constants and greater sensitivity to pH and ionic competition, thus requiring dose and condition adjustments to match efficiencies in complex matrices [19,20]. Therefore, optimizing first with EDTA enables a reproducible and literature-comparable window, which can then be transferred to GLDA or EDDS under the same design to transparently evaluate the performance versus environmental profile trade-off [21].

Ensuring alignment between biomass quality and end-use requirements further demands control of inorganic traces that may compromise formulation stability or generate regulatory uncertainties. In the field of dermocosmetics, recent compendia have documented the incorporation of microalgal fractions for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, provided that elemental purity and compositional consistency are ensured in complex matrices [22,23,24]. This quality requirement underscores the value of selective postwashing when harvesting involves aluminum anodes [25]. In agricultural applications, microalgal bioproducts have been shown to increase productivity and resilience; however, the traceability of residues and compositional uniformity remain critical to reproducing field efficacy and sustaining adoption [26,27,28]. Therefore, engineering of the separation–washing train must preserve the EC/EF efficiency while simultaneously achieving verifiable aluminum thresholds in biomass (mg Al·kg−1 dry solids) and in liquid streams (mg·L−1), without incurring energy penalties that undermine process balance [4].

Taken together, the technical problem is constrained by two empirically supported facts. First, EC/EF enables rapid recovery and high efficiency with competitive specific energy consumption when the current density, interelectrode spacing, and bubbling regime are optimized, thereby validating its role as a harvesting or preconcentration operation in biorefineries [9,10]. Second, the use of aluminum anodes introduces metal carry-over into biomass and effluents at concentrations in the mg·L−1 range, which is incompatible with recirculation without treatment and with quality specifications for the cosmetic and agricultural sectors. This necessitates postharvest barriers employing agents with superior environmental performance [7,13].

Accordingly, the present study evaluated the effects of operating variables (pH, contact time, and agitation regime) and the concentration of the chelating agent EDTA, using a response surface experimental design, on a postharvest desorption scheme applied to Chlorella sp. biomass harvested by electrocoagulation–electroflotation with aluminum anodes. The objective is to delimit an operational window that maximizes aluminum removal and supports a reproducible and scalable conditioning protocol.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Biomass Production

Ten algal strains belonging to Chlorella sp. (UFPS012 UFPS014 UFPS015 UFPS016 UFPS017 UFPS019) Scenedesmus sp. (UFPS021) and Halochlorella rubescens UFPS013 were previously isolated from thermal springs in Cúcuta Colombia and were maintained in the INValgae collection of Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander on Bold’s Basal Medium agar slants under a 12 h light and 12 h dark photoperiod at 60 µmol m−2 s−1 and 27 ± 1 °C. For biomass production each strain was grown in 2 L GL45 tubular glass flasks with a working volume of 1.3 L containing Bold’s Basal Medium [29]. Cultures were mixed by filtered air containing 1 percent v/v CO2 at 0.78 L min−1 under a 12 h light and 12 h dark photoperiod at 100 µmol m−2 s−1 and 27 ± 1 °C. The cultivation was continued for 30 days to secure sufficient biomass and a comparable operational state across strains prior to EC EF and postwash optimization. Cultures were started with an inoculum of 10% v/v in 1.3 L of Bold’s Basal Medium. Culture pH was monitored during growth and the final pH at day 30 was 7.6 ± 0.2 measured with a calibrated pH meter.

2.2. Initial Electroflotation of the Harvested Biomass

Once the 30-day cultivation period was completed, each suspension was subjected to electroflotation (EF) in a batch reactor (1.3 L) equipped with eleven aluminum electrodes (Al ≥ 99.5%) arranged in a bipolar configuration with alternating anode–cathode plates. The interelectrode spacing was set at 0.5 mm, with agitation maintained at 150 rpm, and each electrode presented an exposed surface area of 252 cm2 (total exposed area: 2772 cm2). The direct current power supply operated at 50 W (≈50 V, ~1 A), corresponding to a current density of approximately 0.36 mA·cm−2, calculated as the current divided by the total exposed area [30]. The biomass concentration fed to the EF reactor was standardized at 1.0 g L−1 on a dry weight basis for all strains to ensure comparability across runs. Each experimental run lasted 12 min without the addition of electrolytes or coagulants. Under these conditions, aliquots were collected in triplicate every minute (0–12 min), and optical density was measured at the strain-specific wavelength previously determined to construct CE%–time curves. In parallel, pH and temperature were recorded at 0, 6, and 12 min to document system evolution and ensure process stability.

2.3. Quantification of Residual Aluminum in Culture Media and Biomass

After concentration, the biomass was washed thrice with deionized water, centrifuged (2054× g, 10 min, 20 °C), oven-dried overnight (60 °C), and stored in a desiccator until a constant weight was reached. In addition, Al was determined in the biomass according to Standard Methods 3111 D—Direct N2O–C2H2 Flame [31]. The clarified culture media were filtered through GF-C filters (45 mm, 0.45 µm). The filtered media were used for the quantification of free aluminum via the HI 93712–03 Kit (Hanna Instruments, Padova, Italy).

2.4. Determination of Ash Content

Ash content was determined gravimetrically following Moheimani’s Method 16. Dried biomass from the previous step was homogenized, and 200 mg were transferred into pre-weighed porcelain crucibles. Samples were dried at 105 °C for 2 h, cooled in a desiccator, and weighed to constant mass to obtain the dry mass (). The crucibles were then ashed in a muffle furnace at 450 °C for 5 h, cooled again in a desiccator, and reweighed to record the ash mass (). Ash content was calculated on a dry-weight basis using Equation (1). All determinations were performed in independent triplicate ( one original experiment and two replicates).

2.5. Aluminum Desorption Optimization

To increase the desorption of residual aluminum bound to the biomass generated by electroflocculation, the influences of the EDTA concentration, agitation time, agitation speed, and pH were evaluated. An I-optimal experimental design coupled with response surface methodology was employed via Design-Expert® software, version 22.0.2 (Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA; www.statease.com (accessed on 1 November 2025) (Table 1). The most relevant factors were evaluated via an optimization design of experiments (central composite design).

Table 1.

Design variables and experimental ranges for aluminum desorption studies.

3. Results

3.1. Strain Selection

The fixation of wavelengths by strain after scanning from 200 to 800 nm revealed two defined ranges that enable homogeneous biomass readings and consistent comparisons among organisms. Seven strains were located between 258 and 295 nm, and three were located between 389 and 400 nm, ensuring alignment of quantification prior to the analysis of temporal efficiency. This baseline is consolidated in Table 2 and serves as a reference for evaluating concentration efficiency under equivalent conditions.

Table 2.

Wavelength for determining the optical density of algal strains.

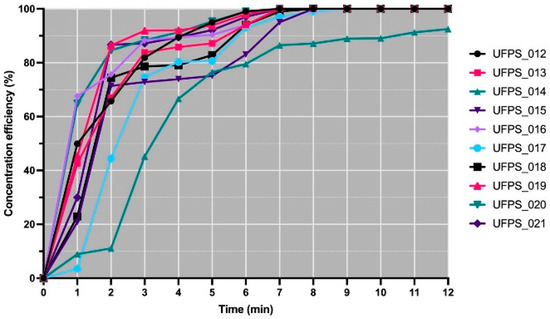

The concentration efficiency curves demonstrated early acceleration and rapid attainment of maximum levels in most organisms. The median t90 was 5.02 min, with a Q1–Q3 of 4.12 to 5.73 min, and the median t95 was 6.17 min, with a Q1–Q3 of 5.28 to 6.20 min, while 9 out of 10 strains reached 95% efficiency within this interval. The initial dynamics exhibited a median slope at 0–2 min of 36.45%·min−1 with a Q1–Q3 of 33.19 to 40.06, which was consistent with the integrated areas from 0 to 12 min of approximately 1020.72%·min, with a Q1–Q3 of 961.46 to 1043.85. Figure 1 depicts the individual trajectories and confirms that the set converges rapidly to the maximum, with a single slower case remaining below 95% at minute 12.

Figure 1.

Electroflotation efficiency (CE % vs. time) by strain.

Three behaviors with explicit compositions were distinguished based on t90, t95, the initial slope, and the integrated area. The fast group included UFPS_019–021 and UFPS_012, characterized by short t90 values, t95 values before 6 min, high slopes, and areas in the upper quartile. The intermediate group included UFPS_013, UFPS_015, UFPS_017, UFPS_018, and UFPS_016, with t90 values between 5 and 6.6 min and t95 values between 6 and 7 min. The slow group included UFPS_014, with t90 values close to 10.42 min and without reaching 95% within the interval. Within the fast group, UFPS_012 stood out for combining short times with early maintenance of 100% efficiency (t50 = 1.01 min, t90 = 4.09 min, t95 = 5.01 min, slope 0–2 min = 32.88%·min−1, area 0–12 min = 1031.05%·min). Consequently, these results position UFPS_012 at the upper extreme of the observed performance, consolidating it as the operational reference for the subsequent desorption stage.

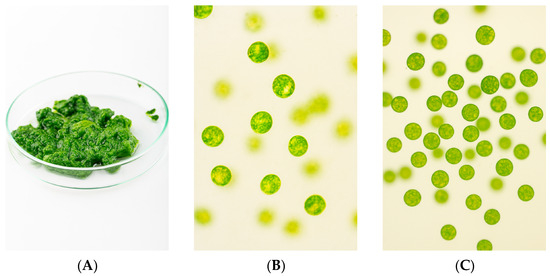

Complementing the electroflotation process characterization, Figure 2 documents the microscale transformation of the suspension. Pre-EC/EF fields show predominantly dispersed cells, whereas post-EC/EF fields display compact aggregates and a stable surface foam; the higher apparent unit count per field reflects concentration rather than growth. This microstructure is consistent with partial double-layer neutralization by aluminum hydroxide species and with cell–bubble adhesion driven by fine microbubbles under the applied regime, which together shorten effective residence time and align with the earlier kinetic analysis of capture efficiency.

Figure 2.

EC/EF microstructure outcomes: (A) collected foam/aggregate layer, (B) pre-EC/EF dispersed cells, (C) post-EC/EF flocculated aggregates with increased areal concentration and compacted floc architecture.

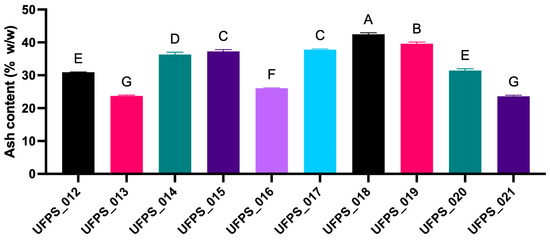

Moreover, the ash content (% w/w, dry basis) by strain, after electrocoagulation–electroflotation (EC/EF), in the range of 25–45% w/w, is depicted in Figure 3. A comparative analysis allows the identification of three bands: an upper band, where UFPS_019 and UFPS_018 presented the highest values (also joined by UFPS_017 and UFPS_016 with values near those with the greatest ash content); an intermediate band with UFPS_012, UFPS_014, UFPS_020, and UFPS_021; and a lower band containing UFPS_013 and UFPS_015, with values lower than those of the set. Additionally, in the statistical comparisons indicated in the figure, no significant differences were found; therefore, at similar concentrations, the variation among organisms was moderate and did not move away from the indicated interval.

Figure 3.

Postelectroflotation ash content by strain. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05), determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

3.2. Analysis of Variance of the Desorption Model

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that the model was highly significant (F = 25.06; p < 0.0001) and that the lack of fit was not significant (F = 1.04; p = 0.4822), which confirmed that the design was adequate for describing the response within the experimental domain (Table 3). The quality measures of the model are R2 = 0.9771, adjusted R2 = 0.9381, predicted R2 = 0.7889, and Adeq Precision = 24.13, which indicates that the model is reliable in explaining the observed variation and has a good signal-to-noise ratio. Partitioning of the sums of squares indicated that blocking contributed significantly to the total variance (SS = 223.97; df = 2; MS = 111.98), although the contribution of the residual was small (SS = 16.95; df = 10; MS = 1.70) and was fairly well balanced due to the lack of a fit component (SS = 8.65; MS = 1.73) and the pure error (SS = 8.30; MS = 1.66). This suggests that deviations unexplained by the model largely reflect the intrinsic experimental noise rather than systematic fitting errors.

Table 3.

ANOVA of the statistical model of Al desorption with EDTA.

In terms of the effects of the main factors, the concentration of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (A) and agitation speed (C) significantly influenced the desorption efficiency (p < 0.001 in both cases), whereas time (B) and pH (D) had no statistically significant individual effects. This result is complemented by the evaluation of quadratic terms, where marked curvature was observed in A2 (F = 44.37; p < 0.0001) and C2 (F = 70.03; p < 0.0001), reflecting a nonlinear response in relation to chelant concentration and agitation, with diminishing returns at the highest levels of both factors. In contrast, B2 was not significant, confirming the linearity of the time effect within the studied domain.

Interactions explained an important fraction of the variance, with the EDTA × time interaction (AB) being the most influential (F = 110.08; p < 0.0001), followed by time × speed (BC), time × pH (BD), and speed × pH (CD), which were highly significant (p ≤ 0.0002). Relevant effects were also recorded for EDTA × speed (AC) and EDTA × pH (AD), demonstrating that desorption efficiency depends not only on the main factors with the greatest degree of determination but also on the interactions among time, pH, chelant concentration, and agitation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the model is consistent and that the studied variables contribute differently to the response, with EDTA and agitation representing the dominant factors in terms of both direct effects and quadratic behavior, whereas time and pH gain importance primarily through their interactions.

3.3. Response Surface of the Desorption Process

Figure 4 shows the response surface for aluminum removal (%) as a function of the EDTA concentration (mM) and time (min) while maintaining a constant pH = 10 and agitation = 100 rpm. The surface behavior reflects a progressive increase in removal with both factors, although the response is more sensitive to the EDTA concentration than to time. At low EDTA concentrations (<20 mM), extending the time to reach the maximum value evaluated (20 min) resulted in only moderate removal increases, whereas at intermediate–high EDTA concentrations (40–70 mM), the effect of time was amplified, and removal reached values close to 97%. The lower plane contours confirm this relationship: the highest-efficiency area is concentrated in the upper-right quadrant (longer times and higher concentrations), forming an optimization zone defined by the interaction of both factors. Within this band, the model’s optimal point is located around EDTA ≈ 65 mM and time ≈ 20 min, representing the most favorable conditions for maximizing aluminum desorption within the evaluated experimental framework. The obtained conditions (EDTA and speed) were optimized using a Central Composite Design in Design Expert.

Figure 4.

Response surface of Al desorption: EDTA (mM) vs. time (min). The red dots indicate the actual experimental conditions used to validate the response surface.

3.4. Optimization Design and ANOVA Analysis

Following the results obtained an optimization design of experiments was created to analyze the impact of EDTA (mM) and mixing speed (rpm) using a central composite design (CCD) coupled with response surface methodology was employed via Design-Expert® software, version 22.0.2 (Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA; www.statease.com (accessed on 1 November 2025) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Design variables and experimental ranges for optimized or aluminum desorption.

3.5. Analysis of Variance of the Optimizated Aluminum Desorption

The ANOVA analysis (Table 5) indicates that the model was highly significant (F = 736.41; p < 0.0001) with a lack of fit was not significant (F = 1.56; p = 0.3307), confirming that the model is adequate to explain the experimental data within the studied domain. The high coefficients of determination (R2 = 0.9981, adjusted R2 = 0.9967, and predicted R2 = 0.9916) and the Adeq Precision value of 51.88 demonstrate that the model has excellent predictive ability, reliability, and a strong signal-to-noise ratio.

Table 5.

Design variables and experimental ranges for optimized aluminum desorption.

Regarding the main factors, the linear effects of EDTA concentration (A) and agitation speed (B) were not statistically significant (p = 0.1796 and p = 0.0540, respectively), suggesting limited direct influence on aluminum desorption within the tested range. However, the interaction between EDTA and speed (AB) was highly significant (F = 37.18; p = 0.0005), indicating that the combined effect of these factors strongly affects desorption efficiency. Also, quadratic terms contributed most to the model with A2 (F = 1902.75; p < 0.0001) and B2 (F = 2014.24; p < 0.0001) both showing strong significance, reflecting a pronounced curvature and nonlinear behavior. This suggests that at extreme levels of EDTA and agitation speed, the system exhibits diminishing returns or saturation effects.

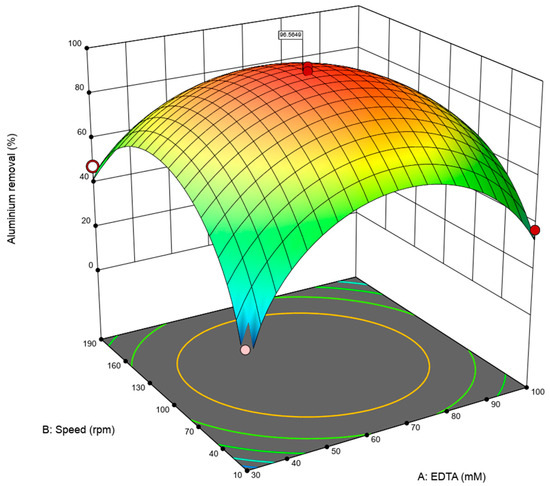

3.6. Response Surface of the Optimizated Aluminum Desorption

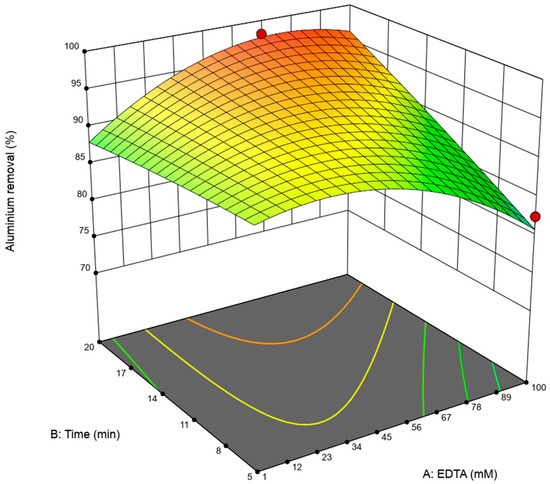

The three-dimensional response surface (Figure 5) shows that the combined effect of EDTA concentration and agitation speed on aluminum desorption efficiency. According to the results the pronounced curvature observed confirms the strong quadratic effects detected in the ANOVA analysis (A2 and B2, p < 0.0001 in both cases).

Figure 5.

Response surface of optimized Al desorption: EDTA (mM) vs. speed (rpm). The red dots indicate the actual experimental conditions used to validate the response surface.

At low and high levels of both EDTA and agitation speed, the desorption efficiency decreases, whereas an optimal region is evident at intermediate concentrations and agitation rates. This indicates a nonlinear behavior, where increasing the levels of either factor beyond the optimum leads to a reduction in efficiency.

The interaction between EDTA and agitation speed (AB) is also reflected in the response surface, as the maximum aluminum removal is achieved only when both variables are simultaneously optimized. This synergistic effect highlights the importance of considering factor interactions rather than analyzing them independently.

Overall, the response surface suggests that maximum aluminum removal (≈96.5%) is achieved at intermediate EDTA concentrations and moderate agitation speeds, validating the statistical significance of the quadratic and interaction terms and supporting the robustness of the optimized desorption model.

Using the optimization module in Design-Expert® software, version 22.0.2 (Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA; www.statease.com (accessed on 1 November 2025) (Table 6), aluminum desorption postelectroflotation was maximized. According to the software, intermediate EDTA concentrations, long reaction times, low revolutions, and pH = 10 are necessary. Therefore, the conditions predicted to maximize the process are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Operational optimum of Al desorption estimated.

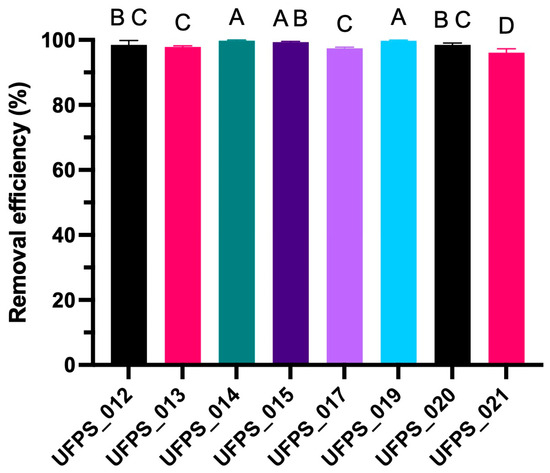

3.7. Experimental Confirmation of Optimal Desorption in Multiple Strains

Confirmation under optimized conditions (EDTA = 65 mM; time = 20 min; agitation = 100 rpm; pH = 10) revealed that all the strains achieved aluminum removal values above 95%, confirming the robustness of the protocol defined in the previous modeling stage. Figure 6 summarizes the behavior of the eight evaluated strains (UFPS_012, UFPS_013–015, UFPS_017, and UFPS_019–021), where it is evident that removal percentages clustered within a narrow range near the experimental maximum, indicating overall high efficiency of the process.

Figure 6.

Aluminum desorption efficiency in algal strains under optimized conditions. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05), determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

However, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05) revealed significant differences among organisms, reflected in the letters above each bar. These letters represent homogeneous subsets, that is, groups of strains without significant differences among themselves but distinct from other groups. The graph clearly shows that most strains cluster at high-efficiency levels, whereas some occupy different positions, indicating variations in desorption magnitude even under identical operating conditions.

More specifically, UFPS_014, UFPS_015, and UFPS_019 formed the upper group, marked with the letters A or AB, achieving efficiencies close to 100% and constituting the best-performing block. In contrast, UFPS_021 presented the letter D, indicating comparatively lower efficiency, although never below 95%. Moreover, UFPS_012 and UFPS_020 appeared at an intermediate level, both labeled BC, indicating that although they reached high removal percentages, these values did not match the maximum values observed in the leading strains. UFPS_013 and UFPS_017 were assigned to group C, and the arrangement of letters above each bar precisely illustrates the statistical relationships among organisms, demonstrating that the results are not uniform but instead reflect inherent variations in each strain.

4. Discussion

4.1. Electroflotation Performance and Strain Variability

On Figure 1 illustrates an electroflotation (EF) harvesting stage characterized by short process times and low dispersion among organisms, a behavior typical of efficient EF/ECF (electrocoagulation–electroflotation) configurations. Studies employing magnesium anodes and carbon cathodes have reported efficiencies close to 98% in approximately 15 min, confirming that the time scales observed here correspond to well-adjusted setups [32]. Complementary evidence from low-cost systems with more than 10 electrodes and agitation speeds of ~150 rpm has shown efficiencies approaching 100% in ≤20 min [30], further confirming the temporal consistency of these results. Additionally, investigations with nonsacrificial anodes have documented recoveries >90% and demonstrated that electrode geometry determines bubble size, which directly influences concentration kinetics [33]. Collectively, these precedents support that the observed performance corresponds to a robust and efficient operational regime for microalgae capture via EFs [34].

Efficiency variations among photosynthetic strains are linked to determinants of bubble–cell interactions and microalgal surface properties. It has been demonstrated that increasing bubble affinity through surface functionalization enhances the adhesion probability, accelerating separation, which is consistent with the fast-response group identified in this study [35]. Cellular hydrophobicity is another critical factor: more hydrophobic cells exhibit faster velocities and higher efficiencies, aligning with the rapid concentration observed in high-performing strains compared with the delayed behavior of the single slower strain [36]. Furthermore, the presence of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) or algal organic matter (AOM) can alter bubble coalescence and gas transfer, thereby conditioning the final efficiency and contributing to interstrain variability [37]; see also Figure 1, where the slope differences between strains illustrate these kinetic disparities.

From a colloidal perspective, the zeta potential (ζ) represents the effective charge of the biomass and, consequently, its suspension stability. In phototrophic organisms such as Chlorella, recent multiscale characterizations have demonstrated that electrostatic and hydrophobic properties govern stability and adhesion events in aqueous media, consistent with the mechanisms relevant to electrocoagulation/electroflotation (EC/EF) [38]. Likewise, in microalgae and cyanobacteria, ζ is consistently observed to be negative under aqueous conditions and to shift toward more negative values as pH increases, leading to enhanced dispersibility [39]. Conversely, the presence of multivalent cations and hydroxylated metal species compresses or neutralizes the electrical double layer, bringing ζ closer to zero and thus promoting flocculation [40]. Within this framework, during EC/EF with aluminum, metallic hydroxides are generated and electrostatic repulsion is neutralized, which explains the rapid capture previously described [4]. Subsequently, during the chelating postwash under alkaline conditions, the complexation of Al3+ by the chelating agent—together with the greater active fraction of the ligand around pH 8–10—tends to restore |ζ| toward more negative values and, consequently, the dispersibility, in agreement with the pH dependence of EDTA efficiency [41].

Regarding the electrode material and electrochemical configuration, studies involving Chlorella sp. consistently compare magnesium and aluminum as high-performance options, identifying aluminum as a balanced choice when both capture efficiency and process compatibility are considered [7,42]. Current density, however, not only determines the Faradaic dose but also influences the size and flow of microbubbles, thereby accelerating floc–bubble collisions and reducing characteristic times when operated within moderate ranges that prevent excessive energy consumption and undesired pH increases [32,43]. In parallel, the geometry of the assembly directly affects the kinetics: decreasing the interelectrode spacing reduces ohmic drop, homogenizes the electric field, and promotes the nucleation of fine bubbles. Consequently, improvements in efficiency and capture times are achieved without energy penalties, provided that the design maintains controlled agitation and a stable flow regime [32,34]. These combined effects explain the compactness of the CE% curves obtained and the high capture efficiency achieved in our system without the need for additional chemical coadjuvants [7,42].

A comparison of parameters such as t50, t90, and t95 is reinforced by prior spectral calibration for each strain. Several authors recommend selecting the wavelength that best correlates optical density with biomass, along with strain-specific calibration curves, to reduce bias before attributing differences to the process [43,44]. Within this framework, UFPS_012 (Chlorella sp.) stands out for combining short times with early and sustained achievement of 100% efficiency, a profile consistent with documented Chlorella performance when the electrode geometry and electrical regime promote fine microbubbles and high adhesion probability [30,33]. Under these conditions, UFPS_012 was consolidated as the operational reference strain for subsequent desorption assays.

Figure 2 places the post-EC/EF ash content between 25 and 45% w/w, which is attributable both to the intrinsic mineral fraction and to the co-flocculation of aluminum hydroxides generated at the anode and retained within the biomass. This behavior is consistent with direct measurements of residual aluminum after electrocoagulation—higher than in systems without anodic dissolution [45], and aligns with reports of metallic incorporation when using sacrificial anodes [4]. When comparing concentration methods, centrifugation and membrane filtration typically yield lower mineral loads than EC/EF, albeit at the expense of higher energy demand or operational costs [2,32]. Consequently, the higher inorganic content observed after EC/EF is both expected and well documented; therefore, the practical strategy is not to discard the electroflotation preconcentrate but rather to implement a selective postwashing step when low ash levels are required, in order to preserve the energetic advantage of the process and ensure the quality of the recovered solid.

Interstrain variability also contributes to dispersion. In Chlorella, electrostatic and hydrophobic differences modulate bubble adhesion and mineral aggregate retention. Recent research has revealed heterogeneity in surface charge and hydrodynamic properties that alter interactions with the gas phase such that a single electric field can translate into different levels of inorganic carry-over depending on the strain [38]. Moreover, interfacial control via bubble functionalization enhances adhesion and, with it, inorganic coentrainment [35]. The electrode diameter also affects the bubble population, collision probability, and solid fraction harvested; configurations with thinner wires have shown greater inorganic retention even without compromising collection efficiency [33]. This explains the dispersion observed in Figure 2 among strains, where UFPS_013–019 exhibit the highest inorganic retention.

4.2. Aluminum Desorption Modeling and Optimization

From a process engineering standpoint, a high ash content compromises the quality of bioproducts through multiple, interrelated pathways. In thermochemical conversions, it alters reaction kinetics and selectivity by catalyzing secondary reactions, shifting cracking routes, and promoting coke formation. Moreover, the presence of alkali and alkaline earth metals lowers the slag melting point, favoring sintering and fouling in heat transfer equipment [46]. In liquid separation processes, high ash levels exacerbate membrane fouling and bed clogging due to precipitates and inorganic complexes, increase solvent demand during extraction, and modify the rheology of pastes and slurries, directly impacting operating expenditures (OPEX) [47]. In microalgal biorefineries, these effects are further intensified when part of the aluminum co-carried during electrocoagulation/electroflotation (EC/EF) remains within the solid matrix, since it can form poorly soluble hydroxides and phosphates that interfere with subsequent stages such as transesterification, pyrolysis, or hydrothermal liquefaction if not removed beforehand [47,48].

In light of this scenario, selective postwashing treatments have proven effective in reducing the inorganic fraction without damaging the biomass. Mild acid washing solubilizes carbonates and hydroxides, while chelation with aminopolycarboxylates removes trivalent cations and part of the divalent ones, producing measurable reductions in ash and associated metals even when the biomass has been concentrated via EC/EF [49,50,51]. To maximize operational performance and minimize energy penalties, the recommended practice is to define an operational window that combines an alkaline pH—favoring the active form of the ligand—with controlled agitation to enhance the mass transfer coefficient and contact times sufficient to reach desorption plateaus, alongside integrated monitoring of conductivity, pH, and residual aluminum in solids and aqueous streams. Under this framework, the optimization with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) conducted in this study establishes a reproducible condition for minimizing aluminum carryover and reducing ash content to levels compatible with higher-value applications, while maintaining the energetic advantage of the electroflotation preconcentrate previously reported for hybrid EC–centrifugation systems [5,8].

The statistical pattern obtained aligns with a desorption process governed by aluminum (Al) complexation with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and by liquid—phase mass transfer. The main effects A (EDTA concentration) and C (agitation speed) were decisive and exhibited significant curvature (A2 and C2), indicating that efficiency increased to a zone of diminishing returns when the chelant dosage or mixing intensity was elevated (see Figure 4, where the response surface visualizes this curvature and the diminishing-return region at higher EDTA and longer times). This behavior is consistent with recent response surface methodology (RSM)-based optimizations of metal desorption, in which eluate concentration and mixing account for most of the variation and display dominant quadratic terms, validating the existence of operational plateaus like those observed here [52]. Likewise, it has been documented that increased agitation enhances the mass transfer coefficient and reduces film resistance, thereby accelerating both adsorption and regeneration/desorption. This mechanism supports the significance of C and the nonlinearity of C2 identified in our model [53,54].

In parallel, pH did not emerge as a main effect, although its influence was revealed through interactions. This response is consistent with the acid–base speciation of EDTA and the stability of its complexes under alkaline conditions, where the deprotonated fraction predominates and chelation becomes more effective, as demonstrated in stability and structural studies of metal–EDTA complexes in alkaline media [16]. The nonsignificance of the lack of fit confirms the adequacy of the polynomial within the experimental domain, and together with a high R2 and Adeq Precision, it supports the validity of the model (see Table 3 for the ANOVA summary and model adequacy statistics). Moreover, the separation between the adjusted R2 and the predicted R2 is compatible with second-order surfaces with multiple interactions, implying that inferences should remain within the design region, as recommended in contemporary RSM methodological guidelines [55,56]. Finally, the blocking factor captured systematic variation not attributable to the main variables, improving estimation precision within the ANOVA, in line with modern RSM applications in separation and water treatment processes [57].

When considering interactions, AB (EDTA × time) was the most influential term, followed by BC (time × agitation), BD (time × pH), and CD (agitation × pH) (Table 3 summarizes the estimated coefficients and the hierarchy of interaction effects). This pattern indicates that time and pH act as kinetic–chemical modulators rather than independent drivers. Specifically, time exerted little isolated influence within the evaluated range but gained importance in the presence of a high EDTA gradient or sufficient mixing to renew the external film and sustain chelant flow to the surface. This finding is consistent with RSM desorption optimizations where the concentration × time interaction dominates the response [52]. Similarly, the pH-related interactions reflect the dependence of both the active EDTA fraction and the biomass surface charge: as the pH increases, the ligand availability and complex stability improve, and the electrostatics of the matrix are modified, making the efficiency sensitive to AD, BD, and CD, as evidenced in studies of chelation and removal processes under alkaline conditions [16]. In the algal context, high desorption yields have been reported when EDTA is applied to recover metals from microalgal biomass and hybrid algal systems, confirming the relevance of the chelating agent and the roles of pH and mixing in the regeneration stage. These precedents are consistent with the structure of effects and interactions observed in the ANOVA and reinforce the proposed mechanistic interpretation [58,59]. Finally, recent studies on adsorbent regeneration conclude that the desorption efficiency tends to stabilize due to mass transfer limitations and site saturation when the operational windows of concentration and agitation are exceeded. This observation is consistent with the significant quadratic terms detected in this study and supports the interpretation of diminishing returns at high levels of EDTA and mixing [49,60].

The maximization band observed—centered around EDTA ≈ 65 mM and prolonged times—is coherent with the ANOVA statistical pattern: A (EDTA) shows both a main effect and curvature (A2), B (time) lacks an isolated effect, and the AB interaction dominates among the significant combinations. Figure 5 shows the corresponding curvature, highlighting the combined influence of EDTA concentration and agitation speed on removal efficiency. This behavior reproduces what has been described in RSM desorption optimizations, where efficiency increases with eluate dosage and contact time until reaching upper-domain plateaus and where the concentration × time synergy emerges as the driver of the optimal region. For example, Bayuo et al. reported analogous maxima with dominant quadratic eluate terms, validated by ANOVA and experimental verification [52]. Moreover, maintaining constant agitation (100 rpm) in the figure isolates the effects of A and B. Nevertheless, the relevance of C in the model is interpreted in terms of solid–liquid transfer: mixing increases the mass transfer coefficient and reduces film resistance, making the effect of B more effective when A is sufficient. This interpretation is consistent with recent correlations on mass transfer in solid–liquid systems and with experimental studies showing kinetic improvements with increased agitation speed [61,62].

Fixing the pH at 10 avoids superimposing speciation changes and favors the deprotonated ligand form, under which metal–EDTA complexes achieve high stability and sustain elevated removal. Consequently, the response surface rises with A across nearly the entire domain and concentrates its maximum in the quadrant of intermediate-to-high EDTA with long contact times. Recent studies in chelation chemistry and EDTA-assisted leaching reported that the neutral-to-alkaline window, with a practical maximum near pH 10, maximizes ligand efficacy in inorganic and aqueous matrices, aligning with the configuration adopted in the figure [63,64]. In the algal context, the use of EDTA for the removal of metals adsorbed on cells has been directly applied in biomass desorption/cleaning protocols, confirming that with sufficient agent availability and adequate contact times, high recoveries are achieved. This outcome is consistent with the reinforced slope observed when A and B increase simultaneously [18].

Finally, the consistency between the geometry of Figure 5 and the model indicators—a nonsignificant lack of fit and high adjusted R2—supports the use of the surface as an operational map within the experimental domain. Operating above a threshold EDTA dose and maintaining long contact times, the system is in the maximum response region, whereas operating at low EDTA levels, even with extended times, sustains only intermediate efficiencies. This interpretation is methodologically congruent with contemporary RSM guidelines and, from a process perspective, provides a clear criterion for planning confirmation runs and validating the optimum (EDTA ≈ 65 mM, 20 min, pH 10, 100 rpm) [65].

4.3. Validation and Cross-Strain Efficiency

The verification set under optimal conditions (EDTA ≈ 65 mM, 20 min, 100 rpm, pH 10) showed that aluminum (Al) removal exceeded 95% in all the evaluated chlorophytes, indicating that the estimated operational point was transferable across strains within the tested panel. The residual variability among organisms is consistent with differences at the cell–metal interface: cell wall composition and the fraction of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) modulate the density of functional groups, surface charge, and hydrophobicity—factors that condition both the initial adsorption and subsequent metal release during postwashing (Figure 6 summarizes these cross-strain efficiencies, showing the narrow 95–100% range and the statistical groupings). This phenomenon is widely described for microalgae and is specifically documented in Chlorella cultures [66].

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons discriminated three levels of efficiency among strains within a narrow range close to the experimental maximum. At the upper level, UFPS_013, UFPS_015, UFPS_017, and UFPS_019 did not differ significantly from each other and achieved values close to the maximum removal threshold. UFPS_012 and UFPS_020 occupied the intermediate level, whereas UFPS_014 and UFPS_021 fell into the lower level, although they still maintained efficiencies above 95%. This interpretation—which is based on post hoc Tukey-type comparisons to identify statistically equivalent or distinct groups—is standard in performance evaluations across strains or treatments in microalgae and is explicitly applied in studies of Chlorella and other genera [67].

The high overall efficiency at pH 10 is consistent with chelation chemistry: under alkaline conditions, the deprotonated form of EDTA predominates, providing greater stability in complex formation and thereby facilitating metal extraction from the biological matrix. Recent studies on extraction/leaching assisted by aminopolycarboxylic agents report maximum efficiency windows in the pH 8–10 range, including comparisons where GLDA (glutamic acid diacetic acid) has emerged as an environmentally favorable alternative with performance close to that of EDTA in inorganic matrices, supporting the use of alkaline pH in the desorption stage [21]. Moreover, contemporary literature on biosorbent regeneration describes chelant-based desorption as the dominant response when liquid–solid transfer is adequate, with high yields reported for microalgal biomass and mixed cultures under similar conditions, which is consistent with the values observed in this confirmation [59,68].

Taken together, the observed pattern—95–100% range, narrow dispersion, and well-defined statistical groups—suggests two process implications. First, the optimized protocol mitigated Al carry-over during postwashing across different strains of the evaluated genus, which is consistent with studies in which Chlorella biomass achieved high metal recoveries following desorption stages with chelating agents [69]. Second, when further homogenization of responses among organisms is needed, it is reasonable to fine-tune microparameters (e.g., solids loading or number of washing steps) while maintaining the main operational window, since the remaining interstrain heterogeneity arises from surface and EPS traits rather than from a limitation of the global optimum [66].

5. Conclusions

The electrocoagulation–electroflotation (EC/EF) scheme proved fully compatible with selective postwashing, maintaining the energetic advantage of the harvesting stage while achieving a significant reduction in residual inorganic content. Response surface modeling confirmed that ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) concentration and agitation speed are the most decisive factors governing aluminum (Al) desorption, whereas time and pH acquire relevance primarily through their synergistic interactions. The resulting polynomial model exhibited robust statistical adequacy, indicating that the process operates under a balance between chelation kinetics and liquid-phase mass transfer. Operating near 65 mM EDTA for 20 min at pH 10 and 100 rpm produced Al removal efficiencies around 97% in the model fit and above 95% in experimental validation, which supports the reproducibility and transferability of the protocol among different chlorophyte strains. This outcome highlights the capacity of the EC/EF + chelation configuration to simultaneously preserve energy efficiency and enhance product purity, consolidating it as a scalable approach for microalgal biomass processing.

Residual differences among organisms persisted due to surface charge, hydrophobicity, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), which affect both adsorption and desorption mechanisms. Such heterogeneity can be minimized through targeted operational refinements—such as adjusting solids loading, extending washing cycles, or modulating mixing intensity—without deviating from the optimal window. From an engineering perspective, the integration of EC/EF harvesting with a chelating postwash represents an operationally coherent strategy for minimizing aluminum carry-over, improving the physicochemical quality of biomass, and ensuring its suitability for subsequent thermochemical, biochemical, or catalytic transformations. The resulting improvement in solid quality not only facilitates downstream processing but also enhances compliance with industrial and environmental standards.

Furthermore, the coupling of electroflotation with controlled chelation establishes a flexible platform for sustainable biorefinery design, enabling the partial recovery of reagents and water-loop closure within integrated systems. Future research should broaden the optimization domain to include environmentally benign complexing agents—such as glutamic acid diacetic acid (GLDA) or iminodisuccinic acid (IDS)—while assessing reagent recovery efficiency and long-term operational stability. It is also recommended to incorporate dynamic control strategies that maintain current density, interelectrode spacing, and hydrodynamic conditions, preserving the efficiency gains observed at laboratory scale. Ultimately, the combination of electrochemical harvesting and selective chelation demonstrates that high-purity biomass recovery can be achieved without compromising energy performance, positioning this hybrid route as a viable foundation for next-generation microalgal valorization processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and J.B.G.-M.; methodology, J.E.C.-R., L.B.C.-C. and A.F.B.-S.; software, A.F.B.-S. and A.Z.; validation, A.Z. and L.B.C.-C.; formal analysis, L.B.C.-C., J.E.C.-R. and J.B.G.-M.; investigation, L.B.C.-C. and J.E.C.-R.; resources, A.F.B.-S. and A.Z.; data curation, J.E.C.-R., J.B.G.-M. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.C.-C. and J.E.C.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.B.G.-M., A.F.B.-S. and A.Z.; visualization, A.F.B.-S.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, A.Z.; funding acquisition, A.F.B.-S. and A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received financial support through grants from Sapienza University for Academic Mid Projects 2021 (Grant No. RM12117A8B58023A). Also funding was received by NeWater project through WATER4ALL Partnership. Additionally, funding was provided by Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander (Colombia) (FINU 001-2025), the Ministry of Science and Technology of Colombia, and the Colombian Institute of Educational Credit and Technical Studies Abroad (MINCIENCIAS-ICETEX) under the project titled “FOTOLIX” with the ID 2023-0686.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Sapienza University of Rome and Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander (Colombia) for providing the equipment for this research. We also thank the Colombian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation MINCIENCIAS for supporting national Ph.D. Doctorates through the Francisco José de Caldas scholarship program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, A.S.; Ali, A.; Gorgun, E.; Jameel, M.; Khandaker, T.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Abdullah, M. Microalgae to Biofuel: Cutting-Edge Harvesting and Extraction Methods for Sustainable Energy Solution. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 3525–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S.J.; Laamanen, C.A.; Senhorinho, G.N.A.; Scott, J.A. Microalgal Harvesting for Biofuels—Options and Associated Operational Costs. Algal Res. 2024, 77, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visigalli, S.; Barberis, M.G.; Turolla, A.; Canziani, R.; Berden Zrimec, M.; Reinhardt, R.; Ficara, E. Electrocoagulation–Flotation (ECF) for Microalgae Harvesting—A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 271, 118684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageshwari, K.; Chang, S.X.; Balasubramanian, P. Integrated Electrocoagulation-Flotation of Microalgae to Produce Mg-Laden Microalgal Biochar for Seeding Struvite Crystallization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucakova, S.; Branyikova, I.; Kovacikova, S.; Pivokonsky, M.; Filipenska, M.; Branyik, T.; Ruzicka, M.C. Electrocoagulation Reduces Harvesting Costs for Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, W.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; He, Z.; Hursthouse, A.; Zhu, G. Variation of Al Species during Water Treatment: Correlation with Treatment Efficiency under Varied Hydraulic Conditions. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.-Aqua 2021, 70, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, J.T.; Pak, H.; We, J.; Oh, S. Evaluation of Pb, Mg, Al, Zn, and Cu as Electrode Materials in the Electrocoagulation of Microalgae. Processes 2021, 9, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucakova, S.; Branyikova, I.; Kovacikova, S.; Masojidek, J.; Ranglova, K.; Branyik, T.; Ruzicka, M.C. Continuous Electrocoagulation of Chlorella Vulgaris in a Novel Channel-Flow Reactor: A Pilot-Scale Harvesting Study. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 126996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupińska, I. Aluminium Drinking Water Treatment Residuals and Their Toxic Impact on Human Health. Molecules 2020, 25, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cheng, J.; Zou, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Gu, J.; Yan, M. Effects of Pre-Oxidation on Residual Dissolved Aluminum in Coagulated Water: A Pilot-Scale Study. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystynik, P.; Dytrych, P.; Paterova, A.; Kluson, P. Novel Approach for Removal of DOC in Samples of Raw Water Using Electrocoagulation for Drinking Water Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 15327–15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.; Engal, O.; Beriozkin, A. EDTA Biodegradability and Assisted Phytoextraction Efficiency in a Large-Scale Field Simulation: Is EDTA Phasing out Justified? J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fernandes de Souza, M.; Li, H.; Qiu, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Meers, E. Biodegradation and Effects of EDDS and NTA on Zn in Soil Solutions during Phytoextraction by Alfalfa in Soils with Three Zn Levels. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaurin, A.; Gluhar, S.; Tilikj, N.; Lestan, D. Soil Washing with Biodegradable Chelating Agents and EDTA: Effect on Soil Properties and Plant Growth. Chemosphere 2020, 260, 127673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, U.; Thouand, G.; Pagga, U.; Gartiser, S.; Heipieper, H.J. Toward the Future of OECD/ISO Biodegradability Testing-New Approaches and Developments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 2073–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, R.D.; Summers, T.J.; Kaliakin, D.S.; Cantu, D.C. The Solution Structures and Relative Stability Constants of Lanthanide–EDTA Complexes Predicted from Computation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 10263–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almubarak, T.; Ng, J.H.; Ramanathan, R.; Nasr-El-Din, H.A. From Initial Treatment Design to Final Disposal of Chelating Agents: A Review of Corrosion and Degradation Mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 1813–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ling, N.; Tian, H.; Guo, C.; Wang, Q. Toxicity, Physiological Response, and Biosorption Mechanism of Dunaliella Salina to Copper, Lead, and Cadmium. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galieva, G.; Kuryntseva, P.; Selivanovskaya, S.; Brusko, V.; Garifullin, B.; Dimiev, A.; Galitskaya, P. Glutamic-N,N-Diacetic Acid as an Innovative Chelating Agent in Microfertilizer Development: Biodegradability, Lettuce Growth Promotion, and Impact on Endospheric Bacterial Communities. Soil. Syst. 2024, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Sauri, A.S.; Kassim, K.; Majanun, E.S.; Mohammat, M.F.; Yaakob, N.; Yaakob, M.K.; Ismail, A.Z.H.; Jaafar Azuddin, F. Performance Analysis of GLDA and HEDTA as Chelators for Calcium and Ferrum Ions at 80 °C: A Combined Molecular Modeling and Experimental Study. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 22576–22584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.; Singhal, A.; Rallapalli, S.; Mishra, A. Bio-Chelate Assisted Leaching for Enhanced Heavy Metal Remediation in Municipal Solid Waste Compost. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Contreras-Ropero, J.E.; Martínez, J.B.G.; Barajas-Ferreira, C.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Natural Antimicrobial Agents from Algae: Current Advances and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-García, D.J.; Rangel-Basto, Y.A.; Urbina-Suarez, N.A.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Muñoz-Peñaloza, Y.A. Lipids Production from Scenedesmus Obliquus through Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio Optimization. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1388, 12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehariya, S.; Fratini, F.; Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Green Extraction of Value-Added Compounds Form Microalgae: A Short Review on Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) and Related Pre-Treatments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Martínez-González, C.A.; Kim, D.-H.; Santiesteban-Romero, B.; Reyes-Pardo, H.; Villaseñor-Zepeda, K.R.; Meléndez-Sánchez, E.R.; Ramírez-Gamboa, D.; Díaz-Zamorano, A.L.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; et al. Microalgae Bioactive Compounds to Topical Applications Products—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabili, A.; Minaoui, F.; Hakkoum, Z.; Douma, M.; Meddich, A.; Loudiki, M. A Comprehensive Review of Microalgae and Cyanobacteria-Based Biostimulants for Agriculture Uses. Plants 2024, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next Generation Plant Growth Additives: Functions, Applications, Challenges and Circular Bioeconomy Based Solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1073546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.B.; Sanchez-Tobos, L.P.; Carvajal-Albarracín, N.A.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Barajas-Ferreira, C.; Kafarov, V.; Zuorro, A. The Circular Economy Approach to Improving CNP Ratio in Inland Fishery Wastewater for Increasing Algal Biomass Production. Water 2022, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Berges, J.; Harrison, P.; Watanabe, M. Recipes for Freshwater and Seawater Media; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Galvis, E.M.; Cardenas-Gutierrez, I.Y.; Contreras-Ropero, J.E.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Zuorro, A. An Innovative Low-Cost Equipment for Electro-Concentration of Microalgal Biomass. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Methods 3111; Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Boinpally, S.; Kolla, A.; Kainthola, J.; Kodali, R.; Vemuri, J. A State-of-the-Art Review of the Electrocoagulation Technology for Wastewater Treatment. Water Cycle 2023, 4, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Min, A.; Ruan, R. Harvesting Chlorella Vulgaris by Electro-Flotation with Stainless Steel Cathode and Non-Sacrificial Anode. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, F.; Lin, F.; Du, H. Algal Removal from Raw Water by Electro-Flotation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1057672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir-Yilmaz, I.; Ftouhi, M.S.; Balayssac, S.; Guiraud, P.; Coudret, C.; Formosa-Dague, C. Bubble Functionalization in Flotation Process Improve Microalgae Harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhan, X.; Stengel, D.B. Low Energy Harvesting of Hydrophobic Microalgae (Tribonema Sp.) by Electro-Flotation without Coagulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krusinova, Z.; Prokopova, M.; Krystynik, P.; Kluson, P.; Pivokonsky, M. Is Electrocoagulation a Promising Technology for Algal Organic Matter Removal? Current Knowledge and Open Questions. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesniewska, N.; Duval, J.F.L.; Caillet, C.; Razafitianamaharavo, A.; Pinheiro, J.P.; Bihannic, I.; Gley, R.; Le Cordier, H.; Vyas, V.; Pagnout, C.; et al. Physicochemical Surface Properties of Chlorella Vulgaris: A Multiscale Assessment, from Electrokinetic and Proton Uptake Descriptors to Intermolecular Adhesion Forces. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 5149–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojkovic, Z.; Skrobonja, A.; Radojicic, V.; Mattei, B. The Use of Flocculation as a Preconcentration Step in the Microalgae Harvesting Process. Physiol. Plant 2025, 177, e70366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Kapur, S.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y. Electrostatic Charges on Microalgae Surface: Mechanism and Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanctis, M.L.; Soranno, E.A.; Messner, E.; Wang, Z.; Turner, E.M.; Falco, R.; Appiah-Madson, H.J.; Distel, D.L. Greater than PH 8: The PH Dependence of EDTA as a Preservative of High Molecular Weight DNA in Biological Samples. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratama, W.D.; Hadiyanto, H. Evaluation of Different Electrodes in Electrocoagulation-Flotation Process for Chlorella Vulgaris Harvesting. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kadam, R.; Jang, H.; Seo, D.; Park, J. Recent Advances in Wastewater Electrocoagulation Technologies: Beyond Chemical Coagulation. Energy 2024, 17, 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, N.; Unpaprom, Y.; Ramaraj, R.; Maniam, G.P.; Govindan, N.; Arunachalam, T.; Paramasivan, B. Recent Advances and Future Prospects of Electrochemical Processes for Microalgae Harvesting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, N.; Yuan, J.; Uguz, S.; Ucok, S.; Gu, Z.; Yang, X. Direct Current (DC) Initiated Flocculation of Scenedesmus Dimorphus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 11292–11298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, L.; Hu, Y.; Naterer, G. Critical Review of the Role of Ash Content and Composition in Biomass Pyrolysis. Front. Fuels 2024, 2, 1378361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, A.F.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Fortunato, L. Membrane Fouling in Algal Separation Processes: A Review of Influencing Factors and Mechanisms. Front. Chem. Eng. 2021, 3, 687422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Qian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mazur, Z.; Kuo, C.-T.; Scheppe, K.; Schideman, L.C.; Sharma, B.K. Effect of Ash on Hydrothermal Liquefaction of High-Ash Content Algal Biomass. Algal Res. 2017, 25, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Oliveira, A.P.; Assemany, P.P.; de Siqueira, C.J.; de Jesus Júnior, M.M.; de Ávila Rodrigues, F.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Campos, M.T.C.; de Cássia Oliveira Carneiro, A.; Calijuri, M.L. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Microalgae Biomass from Wastewater Treatment: Effects of Acid Pretreatment. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 33138–33148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, A.; Daramola, G.; Davis, R.W.; Kumar, S. Environmentally Friendly Chelation for Enhanced Algal Biomass Deashing. Phycology 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Biodegradable Chelating Agents for Enhancing Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, Market Feasibility, and Future Studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayuo, J.; Rwiza, M.J.; Choi, J.W.; Sillanpää, M.; Mtei, K.M. Optimization of Desorption Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology for Enhanced Recovery of Arsenic from Spent Reclaimable Activated Carbon: Eco-Friendly and Sorbent Sustainability Approach. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 280, 116550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Liang, J.; Zhang, G. A Critical Review on Ultrasound-Assisted Adsorption and Desorption Technology: Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, Applications, and Prospects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvalakidou, S.L.; Varoutoglou, A.; Alibrahim, K.A.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. Batch Adsorption Study in Liquid Phase under Agitation, Rotation, and Nanobubbles: Comparisons in a Multi-Parametric Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 114032–114043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ain, N.; Sarah, S.A.; Azmi, N.; Bujang, A.; Ab Mutalib, S.R. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Identifies the Lowest Amount of Chicken Plasma Protein (CPP) in Surimi-Based Products with Optimum Protein Solubility, Cohesiveness, and Whiteness. CyTA-J. Food 2023, 21, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Jiménez, F.-J.; Fernández-Ochoa, Á.; Cádiz-Gurrea, M.d.l.L.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Oliver-Simancas, R.; Alañón, M.E.; Castangia, I.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Arráez-Román, D. Application of Response Surface Methodologies to Optimize High-Added Value Products Developments: Cosmetic Formulations as an Example. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayomi, K.S.; Lau, S.Y.; Danquah, M.K.; Zhang, J.; Chiong, T.; Obayomi, O.V.; Meunier, L.; Rahman, M.M. A Response Surface Methodology Approach for the Removal of Methylene Blue Dye from Wastewater Using Sustainable and Cost-Effective Adsorbent. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani, M.; Adessi, A. Cyanoremediation and Phyconanotechnology: Cyanobacteria for Metal Biosorption toward a Circular Economy. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1166612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabai, A.I.; Mohammed, K. Biosorption and Desorption of Chromium Using Hybrid Microalgae-Activated Sludge Treatment System. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renu; Sithole, T. A Review on Regeneration of Adsorbent and Recovery of Metals: Adsorbent Disposal and Regeneration Mechanism. S Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 50, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Enhancing Liquid-Solid Mass Transfer and Achieving Uniform Particle Dispersion Using an in-Line Toothed High Shear Mixer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 319, 122351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglezakis, V.J.; Balsamo, M.; Montagnaro, F. Liquid-Solid Mass Transfer in Adsorption Systems—An Overlooked Resistance? Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22007–22016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Fu, F.; Tang, B. Fate of Metal-EDTA Complexes during Ferrihydrite Aging: Interaction of Metal-EDTA and Iron Oxides. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sheidi, A.S.A.; Dyer, L.G.; Tadesse, B. Leaching Efficacy of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) to Extract Rare-Earth Elements from Monazite Concentrate. Crystals 2024, 14, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Ali, E.; Al-Saedi, H.F.S.; Mohammed, A.Q.; Mustafa, N.K.; Talib, M.B.; Radi, U.K.; Ramadan, M.F.; Ami, A.A.; Al-Shuwaili, S.J.; et al. A Chemometric Approach Based on Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Antibiotic and Organic Dyes Removal from Water Samples. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciempiel, W.; Czemierska, M.; Wiącek, D.; Szymańska, M.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Krzemińska, I. Lead Biosorption and Chemical Composition of Extracellular Polymeric Substances Isolated from Mixotrophic Microalgal Cultures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer Uyar, G.E.; Mısmıl, N. Symbiotic Association of Microalgae and Plants in a Deep Water Culture System. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde-Garcia, F.; Prasher, S.; Kaliaguine, S.; Tavares, J.R.; Dumont, M.-J. Desorption Strategies and Reusability of Biopolymeric Adsorbents and Semisynthetic Derivatives in Hydrogel and Hydrogel Composites Used in Adsorption Processes. ACS Eng. Au 2023, 3, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, A.R.F.; Passos, H.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Metal Biosorption onto Non-Living Algae: A Critical Review on Metal Recovery from Wastewater. Green. Chem. 2023, 25, 5775–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).