Abstract

Demographic changes have led to an increase in older people in prisons. Whereas the rehabilitative process of younger offenders is geared towards their reintegration into the labour market, successful ageing should be a policy aim for older prisoners. This study explores how older incarcerated persons view their ageing. A qualitative study using a written survey with only the single question What does ageing in prison mean to you? was conducted in Bavaria, Germany. A total of 64 prisoners (61 male, 3 female) supplied answers varying in length from a few words to several pages. The thematic analysis revealed that together with health concerns, social relations and everyday activities, the uncertainty of the future was a central focus point for the older adults in prison. The authors propose that a positive vision of the future needs to be included in any model of successful ageing. If successful ageing is used as an aim for older prisoners, more attention needs to be paid to support interventions during and after the release process.

1. Introduction

The growing numbers of older adults in prisons have become an increasing focus of research worldwide. Demographic changes have led to a substantial increase in this population over the last decades. In Germany, just over 2% of the prison population was over 60 years old in 2000; by 2022, the percentage had risen to 5.1% [1]. Unlike in countries with restrictive sentencing policies, where long sentences as well as a growing prison population further exacerbate the rise in older incarcerated persons [2], in Germany, the prison population has steadily declined over the last two decades to one of the lower imprisonment rates in the world (67 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2022), with only a slight post-COVID-19 increase over the last two years [1,3]

In Germany, as in most other countries, many existing prisons were built in the 18th, 19th or early 20th century with young inmates in mind, as criminal activity significantly declines with age. Buildings are frequently unsuited to the needs of older people with physical or cognitive disabilities, but the impact of the prison system on older people goes beyond the questions of accessibility. There is abundant evidence that the intersection between aging and imprisonment leads to a ‘double burden’ [4] for incarcerated older adults, or as Leigey and Aday call it ‘the gray pains of imprisonment’ [5]. Studies have shown that the health of imprisoned older people is considerably poorer that than that of their community-dwelling peers [6,7] and that prisons inadequately meet the complex health care needs of this group [8]. Resulting functional, mobility and cognitive disabilities often lead to increased social isolation [9,10] and potential victimization [11]. When older people are exempt from work, they often spend most of their time in their cells without having access to meaningful activities or exercise. Not surprisingly, older adults in prisons are affected by loneliness [12] and there is a high prevalence of mental health needs among this group, which mostly remain unmet [13,14].

It has been long recognized that there is a high cost of what Mashi et al. call “the international aging prisoner crisis” [15]. In addition to the substantial financial costs of supporting older people in prisons, the lack of quality of life, the violation of human rights and the premature death of this vulnerable group indicate that there is also a high human cost. Interventions to support this group have been developed in individual prisons [16,17,18,19], yet are not systematically available to all older persons in prison. The highly acclaimed True Grit intervention, a holistic programme to support older people’s physical, mental and spiritual needs through structured daily activities in prison, only exists in Nevada and focuses on older veterans [20]. More widespread are separate wings for older people in prison, some of which have specialist hospice or dementia care facilities [16,17,18,19]. A patchwork of smaller interventions exists in individual prisons aiming to improve specific aspects of older people’s lives, but only a few of them consider the release process and the support needed when older people leave prisons [17].

The situation of older incarcerated people in Germany varies considerably. While best practice projects with separate accommodation and holistic support for this group exist, most older people have no access to them [20]. There is consensus amongst scholars that support for this group needs to be developed further. The state of Hessen in Germany specifies successful ageing as an enforcement aim for older people in prison [20] replacing the standard focus of supporting prisoners’ rehabilitation and reintegration into the labour market.

The notion of successful ageing is a gerontological model that was originally developed by Rowe and Kahn in the 1990s [21], who argue that there are three dimensions to successful ageing. First, good health is key to ageing well. Whereas for Rowe and Kahn, the absence of disease and disability has been paramount to successful ageing, subsequent debates of the concept contend that one can also age well with impairments and the question is not only about optimizing older people’s health but also their care provisions [22]. The importance of the environmental context of ageing can also be seen in relation to the other two dimensions of the concept, namely high cognitive and physical functioning and an active engagement with life. Cognitive and physical functioning cannot be solely regarded as an innate ability, but an enabling environment can promote independence and autonomy, which is central to a high quality of life in later life. The dimension of active engagement with life points out how central social relations and meaningful involvement in one’s community are to older people’s well-being. Critical debates on the model of successful ageing are numerous. One can distinguish between those who want to add additional dimensions to the concept, such as spirituality, personality, optimism, self-efficacy and resilience [23], and those who reject its normative character [24]. Strawbridge et al. argue that it is more important to identify older people’s subjective criteria for ageing well [25].

The concept of successful ageing has so far been rarely used as a framework to reflect on the ageing trajectories of prisoners. Avieli [26] sees the concept of successful ageing as useful, as it moves away from deficit-orientated descriptions of older prisoners to an analysis of their well-being. Her qualitative research in Israel shows that some incarcerated older people compare ageing in prison to being in a retirement home, where loneliness and poverty can be avoided. A position of respect, where people can develop as a person, contributes to positive ageing environments [26]. Thus, Avieli argues that ageing trajectories in prison are not unified, and that prisons also have the potential to nurture older people.

Lucas et al. [27] explore how Filipino women manage to age successfully in prison and develop “a road to success” model with five phases that women undergo to age well in prison, namely struggling, remotivating, reforming, reintegrating and sustaining [27]. Whereas the first three phases involve coming to terms with their imprisonment and accepting the change as a means to bettering themselves, the latter two phases relate to connecting to others and maintaining their health. However, in this study, only those who were seen as ageing successfully participated, and it gives little insight into prisoners’ understanding of ageing in prison. In our study, we aimed to fill this gap by asking all older prisoners in Bavaria to describe their ageing in prison.

2. Materials and Methods

The research project aimed to explore older adults’ views on their ageing in prison. As little was known about prisoners’ perspectives on ageing, a qualitative design was chosen to conduct the research. Due to the infection control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the research (winter 21/22), it was not possible to conduct interviews in prison, and as a result, an unusual design using a written questionnaire was chosen by the research team.

The questionnaire contained only the question What does ageing in prison mean to you? as well as the option to identify one’s gender and age group. The research team abstained from collecting further sociodemographic data to not jeopardize participants’ anonymity. The questionnaire was written in German but was translated into other languages at request (one participant made use of that) and participants had the option to fill it in in their native language. Three participants used this option, and their replies were translated by the research team. The lengths of the replies varied considerably. While a few participants submitted notes of less than a page, many others provided detailed and extensive reports of up to five pages.

The research was undertaken in the state of Bavaria, Germany, where in 2022, 5.26% of the prison population was over 60 years old. A total of 38.3% of the older incarcerated persons were first-time offenders. 15.7% of the older prison population in Bavaria had a life sentence (in Germany, there is the possibility to release adults with a life sentence after 15 years on parole) and another 16.1% were detained on grounds of public security after they had completed their sentence. A total of 23.1% were detained for less than a year. [28]

With the support of the local Kriminologischer Dienst (an institution that is responsible for monitoring, conducting and supporting research in the justice system), 11 prisons where predominantly prisoners with longer sentences were held were selected to be invited to the research project. One prison declined to participate. Each prison manager of participating prisons appointed staff members either from social services or the prison chaplaincy to deliver the questionnaires to all prisoners over the age of 60. Although the research team considered a lower cut-off age in line with other research on this group (e.g., [6,7,10,11]), the cut-off age of 60 was chosen for pragmatic reasons to ensure a manageable sample size.

Questionnaires were returned via prison staff in sealed envelopes to ensure that answers remained anonymous. Although individual responses could thus be linked to prisons, it was decided not to correlate responses to prisons to maximize anonymity. Data collection took place from December 2021 to February 2022.

The data was analysed thematically, and the main categories were deducted by the theoretical framework of successful ageing as well as inductively refined with MAXQDA 2022 [29]. Initially, a section of the data was coded independently by the two researchers before a code system was agreed on.

The research was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Applied Science Munich.

3. Results

The study sample contained 64 responses from older adults in 10 Bavarian prisons. As Table 1 shows, only three older women participated, and two men were over 80 years old. After initially scanning the data, the authors felt that neither gender nor age could be meaningfully incorporated into the analysis.

Table 1.

Gender and age of the study sample (Four persons provided no information about their age and gender, but they were held in prisons for male prisoners.).

The thematic analysis resulted in five main themes: health concerns, everyday life in prison, social relations, perspectives on the future and criticism of the prison and justice system. The latter theme is only included in the analysis in this paper when it relates to ageing processes. The theme of social relations has been dealt with in more detail in a separate paper [30].

3.1. Health Concerns

Three-quarters of the received responses refer to health and healthcare challenges, suggesting that this is a central concern for older adults in prisons. Mental health problems dominate the accounts of older adults, but physical ailments are also mentioned. Participant P56 reflects that health gets “off track” when being imprisoned, thus acknowledging that ageing trajectories are negatively affected in prison. P15, P35, P39, P55 and P56 complain about unhealthy food, arguing that it should be more balanced, contain more vitamins and be geared towards the needs of older prisoners. There is also an awareness that the lack of exercise and movement impacts the health of older adults. P7 worries that the lack of exercise may have a long-lasting impact on his health, while P58 visits the prison’s gym to remain fit.

A third of the respondents complain about the health care provision in prison. In some cases, concrete deficits are described, such as a lack of glasses (P37), insufficient care for dentures (P54) or medication errors (P41). Others remark on structural problems in the system of health care provision in prisons. P27 criticises that staff who are not medically trained are gatekeepers for medical appointments and can cause a delay in prisoners’ being treated. P25 feels there are insufficient rehabilitation services available in prisons after people had hospital treatment. Such comments show an awareness of imprisoned older people of how their incarceration affects their physical ageing negatively.

Study participants also frequently comment on their mental health problems and factors leading to them were identified; some prisoners also reflect on how situations could be improved, but a reflection of mental health problems in relation to ageing is rare. P6 describes his situation as “drowning”, “being in a deep hole” and “lost without any orientation”. The prison system is criticised for offering little support. Comments were made about the stress of family members or pets (P10) dying while in prison, but also the fear of becoming seriously ill or dying in prison without any support from family members. There is no confidence that people will be adequately cared for if support needs arise.

3.2. Everyday Life in Prison

Activities of daily living are key to maintaining functional skills to remain independent in old age. Study participants complain that access to work is often restricted to younger prisoners. P30 argues that disabilities should not be a criterion to exclude older people from work. Only P58 mentions that he has suitable work as a gardener and is grateful for the opportunity. As P60 points out, older people have no chance in the labour market after their release; thus, some of the older people long for different activities that would prepare them for their future lives. As P57 (m, 70–79) argues:

There is no “retired” status in the law or prison. […] As a retired person one is at best “without work, which isn’t one’s fault” and excluded from daily labour, but one has no claim to more leisure, a higher allowance for shopping or covering the needs for mental of physical interests.

Work does not only provide a helpful structure to the day and enables prisoners to earn a small amount of money, but it also gives people value and the feeling of being needed.

I’m feeling then excluded, pushed away, not taken seriously. Often it is then so that the younger ones are unreliable and are kicked out of the [work] interventions. I always have to prove that I’m still “useful”, otherwise I’m immediately a goner.(P6, m, 60–69)

Several of the participants suggest age-friendly activities to structure their day, such as cooking, suitable physical exercise, cultural activities, or P13 would have appreciated leaving the prison for outings with staff. Several participants mentioned a lack of stimulation and loneliness as a result. P53 (m, 60–69) states “one plods along”. P59 and P61 would like to spend more time outside their cells. P14 misses cultural activities, such as going to the theatre or museum. As P26 argues social contact is central to their survival and P61 craves more conversations with others.

The responses from participants suggest that the everyday life of prisoners often focuses on basic needs, such as one’s security and having access to desired foods and drinks. P35 would like more privacy when showering, as he has mobility problems. Some participants worry that they will not be able to meet basic needs on their release as skills to complete activities of daily living are at risk of deteriorating in prison.

I am dependent on help. To act independently is not allowed in prison and we unlearn it. No access to the telephone or internet, because I could do criminal deeds and have learnt nothing.(P6, m 60–69)

Or new skills needed to function in everyday life outside prisons cannot be acquired.

What only worries me is coping with digitalization after my release. There should be timely and thorough training to use a mobile phone and a smart phone, so that everyday tasks can be completed.(P14, m, 80+)

More positive comments are rare. P60 (m, 60–69) sees the advantage of getting older as that age brings “a certain serenity with it, so that one doesn’t get upset about small matters”.

The daily structure of the day in prison is different to that of people living independently in the community. No decisions must be made; no initiatives have to be taken. Repetitive routines and isolation determine the everyday experiences and skills needed to adapt to changes are not nurtured and deteriorate.

3.3. Social Relations

One can distinguish between three different types of people that prisoners have contact with: (a) other prisoners, (b) family and friends and (c) prison staff. Study participants comment on their relations to all three groups.

Older prisoners in this study comment predominantly negatively on fellow prisoners. There are a number of comments on “the young” that are disrespectful, loud, lazy, violent, a threat to older people and are preferred or push ahead of the queue when it comes to activities offered. Only one female person (P11) talks about having made friends in prison. There is otherwise little evidence in the data that fellow prisoners are a positive resource of support for participants.

Emotional and some practical support comes from family members. As P26 says, the person “who hasn’t got any social contact outside, drowns in here” (P26, m, 70–79). Yet social contact with family is limited and P47 desired that more would be done to maintain relationships; P35 thinks visiting hours should be extended. P45 and P46 complain that in other German states, more telephone contacts and visits are allowed. Prisoners who have family abroad find it particularly hard to remain in touch with their families, as no visits are possible. P27 argues that the COVID-19 pandemic made contacting family members more difficult, as no physical contact was allowed on visits, face masks had to be worn and the number of visitors was more restricted.

In addition to providing support to prisoners, the study also reveals that worries about family members can be a burden to older people in prisons. As spouses and partners are likely to be older as well, they may also have their own care and support needs. As P50 (m, 60–69) describes it: “my wife is in a wheelchair and is outside on her own and can’t comprehend the whole imprisonment situation”. Feelings of guilt are evident in some cases.

The feeling that I have brought my wife and my children into a precarious and lonely situation, is a burden to me. Especially, as I can’t do anything to support my wife actively from within prison.(P7, m, 70–79)

Additionally, there is a worry that relatives or the prisoners themselves may die during their time spent in prison and the chance to say goodbye will be denied. As families are frequently seen as a source of support, their absence is often painfully felt; for example, P62 is sad as he misses out on seeing his grandchildren growing up.

Social relations with staff occur within a framework of power, a fact that study participants are aware of. P32 would have liked to write a longer reply to our question but staff denied him to have additional paper. When appointments with medical staff or social workers are requested, staff potentially have the power to delay or speed up processes. P47 accuses staff of not intervening when older prisoners are victimized by their younger peers. P5 (m, 60–69) thinks that “over half of the prison staff treat prisoners very rough”. P63 goes even further in his criticism and claims that staff only act in their own interests. Others comment that staff lack motivation.

Some participants, such as P6, see staff as “flawless” or themselves well supported by individual staff members; for example, a psychiatrist (P39) or a chaplain (P3). P47 argues that the fault of the lack of support does not lie with individual staff members, but with the Bavarian prison system, which grants staff not enough autonomy and places high time constraints on advisory meetings between social staff and inmates.

Older prisoners face being treated in a patronizing way by staff (P27). P16 would like staff to cater better for the needs of older people. As P30 argues, older prisoners should also be seen as having potential by staff.

I think prisons shouldn’t see the elderly as a burden, but as an opportunity to enrich life in prison. That might surely not apply to all prisoners, but I think in many there is a great treasure that needs to be brought to the light.(P30, m, 60–69)

3.4. Perspectives on the Future

There is evidence that many older people in prison have substantial existential anxieties about their future. P28, P41, T54 and P53 worry about not leaving prison alive. As P54 (m, 60–69) writes:

The prison conditions are basically so bad and undignified, that one lives with permanent anxiety to not survive the time in prison.

P60 worries about getting seriously ill and needing to be cared for in prison. Similarly, P39, who has already health problems, only hopes to survive the time in prison, as he regards the medical care he receives in prison as bad. As P20 (m, 70–79) sums it up cynically: “Ageing in prison, for many till their death, a cold death sentence.”

Yet those who do not worry about dying in prison often do not see their future any brighter. P62 (m, 70–79) explains that with time “thoughts get disturbed, hopes confused, ideas demolished, and dreams destroyed”. Like others, P43 (m, 70–79) worries about his financial situation after his release. While some participants (P61, P7) have a large enough pension fund to have financial security on their release, most of the prisoners in Germany are in a more vulnerable position on their release. As no contributions to the pension fund are currently made for any work undertaken in prison, there is little income available once they retire. A similarly precarious situation exists for self-employed workers. P40 (m. 60–69) hopes to continue to work in his business after his release, yet P62 (m, 70–79) is not sure that he has still the energy to do so. There are also comments that pension funds are used to meet debts (P25, P63), and that the advice on debt that prisoners receive is insufficient.

After prisoners’ release, they only receive payment to cover the first four weeks, which as P9 (f, 60–69) argues is not enough “to build a new life”. The concern about suitable housing is also linked to financial worries. P13 sees the chance to get into sheltered housing as a matter of luck, as insufficient places are available in many regions.

Emotional and social worries are added to existential ones. The fear of being stigmatised by family members and the community makes participants anxious and reluctant to face the future. P58 (m, 60–69) dreams of “a halfway dignified life in an environment without hostilities”. P7 (m, 70–79) points out:

I worry about being stigmatised and at my age I have few opportunities for change, that means a spatial distance, a “new start” is practically impossible at my age.

Whereas some participants such as P44 describe how they use their time in prison to make plans for their future lives, most participants feel ill-prepared. There is a consensus among several participants that not enough is done to prepare them for their reintegration into society (P56, P36, P46, P47). As P 46 (m, 70–79) sums it up:

Nothing is done for rehabilitation. One feels like being in a storage box (rented for a while and then out you come).

4. Discussion

The results indicate that the three dimensions of the successful ageing model by Rowe and Kahn are of importance to older people in prisons. Particularly, health and healthcare provision are of key concern to many of the study participants. Unlike in Meyer’s study, where the older prisoners interviewed also talk about individual ageing problems such as incontinence [6], comments in our study often focus on access to medical services in prison, the lack of exercise and poor nutrition rather than individual physical ailments. Their mental health is, however, described in more detail, which underlines the high prevalence of mental health issues and the lack of available support that has been noted in other studies [6,31,32].

Functional skills are key for older people to maintain independence in their everyday life. Results show that life in prison is focused on labour activities, and that some older persons regret not having access to meaningful tasks. When functional skills are not maintained regularly, remaining autonomous in later life becomes increasingly difficult. Older adults with long prison sentences also need support to acquire new digital skills needed in a rapidly changing world. As Geither and Wagner [33] show discrepancies between desired everyday tasks and the actual practice of undertaking them increase a feeling of lack of autonomy. Thus, it is vital to identify how older people want to live after their release and promote the skills needed for doing so during their time in prison.

Results show that the focus of social relations is on older people in prison and their families. However, as Lukas et al. in their study on incarcerated Filipino women show, it is also the integration in the prison community that has a positive impact on ageing processes, as here social relations are immediate and present and thus strengthen people’s identity [27]. Our results show that there is potential to improve the prisoners’ relations to their peers in prison as well as to staff. Although problems of older people’s victimization by other prisoners have been reported previously [34], our study shows that relations between younger and older prisoners remain difficult. Older people in prisons also long to be acknowledged and valued by staff [30]. Separate housing of older people in prisons with staff and fellow prisoners being trained on age-related challenges, such as cognitive decline, is seen as advisable [35].

A key dimension of ageing in prison is the uncertainty of the future. The lack of financial means, housing and uncertain social relations stress older people in prisons and affect their mental health. When care needs are high, it is challenging to find suitable residential services that provide continued care after their release [36]. Whereas in some parts of Germany, organizations exist to support older people’s transitions into the community, these are rare and social workers in prisons lack time and possibly expertise to ensure the best possible living options for their clients.

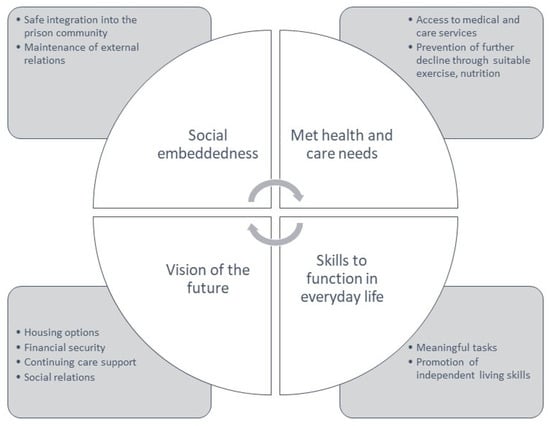

As Bowling pointed out, successful ageing is not so much about health, but about maximizing one’s psychological resources [37]. A positive outlook is linked to resilience [38] and better mental health [39]. In the model of successful ageing that we propose (see Figure 1), a positive vision of the future is interlinked with the other key elements of successful ageing. Being embedded in social relations enables people to be more optimistic about the future, but also vice versa. The motivation to do something for one’s health and maintain daily living skills can be derived from hopes for a dignified life beyond prison.

Figure 1.

Model of successful ageing for older adults in prison.

This model implies that older prisoners need to be well supported to live as independently and socially embedded as possible after their release from prison. Curative as well as preventative healthcare interventions, training of everyday living skills and support in building and promoting social relations and improving transition options by providing safe and adequate housing and support after their release are required for older offenders with a prison sentence to age successfully.

It is also in society’s interest to release older people from prison in the best possible condition to avoid further costs being added to an already extremely expensive system. As the Osborne Foundation points out, warehousing older people in prison is costly, but the security risks associated with the group are low [40]. Providing older people with suitable supported housing and independent living options not only presents them with a brighter future, but also keeps costs lower, as high dependence care homes or keeping older adults in prisons is expensive.

Limitations

The methodological approach of the research might have caused a bias in the way that more educated prisoners are possibly overrepresented in the study. Some of the responses were eloquent, but at the same time, there were also numerous responses with lists or short sentences and numerous language mistakes, indicating that people with a range of educational levels were included. Prisoners whose mother tongue is not German might also be underrepresented in the sample. Illiterate persons could not participate. Interviews instead of the written survey might have allowed for wider participation in the research.

The research project might have also particularly appealed to those prisoners who identify as “old”. The research team had no control over how and if questionnaires were given to all older prisoners by prison staff. Some prisoners might not have participated in the study, as they had to return their replies (even though they were in sealed envelopes) to prison staff.

Whereas the number of older incarcerated persons in Bavaria is close to the German average, Bavaria has some of the most conservative prison policies in Germany [41], where public safety appears to be a higher priority than the rehabilitation of prisoners (for example, in many of the other states, prisoners have had access to private phones to keep in contact with their families for several years [42]). As a result, the comments by study participants might not be totally representative of all older adults incarcerated in Germany. Internationally, prison conditions vary considerably, with many countries providing a harsher environment and longer sentences than Germany. However, this makes a discussion about the impact of imprisonment on ageing universally necessary.

5. Conclusions

At present, older adults in Bavarian prisons face many challenges that affect their ageing in negative ways. Their concerns about their ageing in prison do not only focus on their health and the healthcare provision, but also on their social relations, meaningful everyday life and anxieties about the future. The model of successful ageing can be applied to discuss the changes needed to enhance the ageing trajectories of older people in and beyond prison, but the dimension of a vision of the future needs to be included. Although the German state Hessen includes successful ageing as an aim of their prison policy for older people, states like Bavaria have not developed more age-specific policies. More empirical research is needed to analyse whether the best-practice provision for this group, such as the age-specific accommodation in the prison Kornhaus-Schwalmstadt in Hessen with its holistic health and social support and skills training to support older offenders’ reintegration, leads to more successful ageing processes than in Bavaria and elsewhere.

Gerontology acknowledges that ageing trajectories have become increasingly heterogeneous. However, older prisoners rarely figure in successful ageing discourses. The results from this study suggest that a positive vision of the future is a vital ingredient to ageing well, which has practical implications not only for those organising the prison system and supporting prisoners, but also for those who work with other groups of older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, A.K. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, C.G.; project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, but was supported by the supply of administrative support of the Centre for Ageing at the Catholic University of Applied Science Munich.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Catholic University of Applied Science Munich on 7 October 2021 as well as the Kriminologischer Dienst Bavaria.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is not publicly available, as participants only consented to the study team having access to it.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support from prison staff in delivering and collecting questionnaires. Thanks also to the Centre for Ageing at the Catholic University of Applied Sciences Munich where A.K. undertook the research and Claudia Gerdes for supporting the administration of this project. We also appreciate the helpful comments of the reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Statistisches Bundesamt.Rechtspflege. Demographie und Kriminologische Merkmale der Strafgefangenen zum Stichtag 31.3.2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Staat/Justiz-Rechtspflege/Publikationen/Downloads-Strafverfolgung-Strafvollzug/strafvollzug-2100410227004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Vannier, M.; Nellis, A. ‘Time’s relentless melt’: The severity of life imprisonment through the prism of old age. Punishm. Soc. 2023, 25, 1271–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgen, T. Ältere Menschen im Strafvollzug: Fallzahlen und Entwicklungen. In Alter und Devianz; Pohlmann, S., Ed.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022; pp. 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.; Peacock, M.; Payne, S.; Fletcher, A.; Froggatt, K. Ageing and dying in the contemporary neoliberal prison system: Exploring the ‘double burden’ for older prisoners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 212, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigey, M.E.; Aday, R.H. The Gray Pains of Imprisonment: Examining the Perceptions of Confinement among a Sample of Sexagenarians and Septuagenarians. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2022, 66, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L. Strafvollzug und Demografischer Wandel: Herausforderungen für die Gesundheitssicherung Älterer Menschen in Haftanstalten; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M.; Ahalt, C.; Stijacic-Cenzer, I.; Metzger, L.; Williams, B. Older adults in jail: High rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health Justice 2018, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pageau, F.; Cornaz, C.D.; Gothuey, I.; Seaward, H.; Wangmo, T.; Elger, B.S. Prison Unhealthy Lifestyle and Poor Mental Health of Older Persons—A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 690291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Treacy, S.; Haggith, A.; Wickramasinghe, N.D.; Cater, F.; Kuhn, I.; Van Bortel, T. A systematic integrative review of programmes addressing the social care needs of older prisoners. Health Justice 2019, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.J.; Burns, A.; Turnbull, P.; Shaw, J.J. Social and custodial needs of older adults in prison. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidawi, S.; Trotter, C.; Flynn, C. Prison Experiences and Psychological Distress among Older Inmates. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2016, 59, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pageau, F.; Seaward, H.; Habermeyer, E.; Elger, B.; Wangmo, T. Loneliness and social isolation among the older person in a Swiss secure institution: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, J.M.; Houben, F.R.; Visser, R.C.; MacInnes, D.L. Mental health and offending in older people: Future directions for research. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2019, 29, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, S.G.; Golembeski, C.; Periyakoil, V.S.; Arias, J.; Knittel, A.K.; Ballin, J.; Oliver, H.D.; Tran, N.T. Standardized outcome measures of mental health in research with older adults who are incarcerated. Int. J. Prison. Health 2022, 18, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maschi, T.; Viola, D.; Sun, F. The high cost of the international aging prisoner crisis: Well-being as the common denominator for action. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, C.; Kenkmann, A. Psychosoziale Unterstützungsangebote für lebensältere Menschen in Haft—Eine Literaturanalyse. Bewährungshilfe 2019, 66, 320–344. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.A.; Shaw, R.; Bewert, P.; Salt, M.; Alexander, R.; Loo Gee, B. Systematic review of aged care interventions for older prisoners. Australas. J. Ageing 2018, 37, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canada, K.E.; Barrenger, S.L.; Robinson, E.L.; Washington, K.T.; Mills, T. A systematic review of interventions for older adults living in jails and prisons. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopera-Frye, K.; Harrison, M.T.; Iribarne, J.; Dampsey, E.; Adams, M.; Grabreck, T.; McMullen, T.; Peak, K.; McCown, W.G.; Harrison, W.O. Veterans aging in place behind bars: A structured living program that works. Psychol. Serv. 2013, 10, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkmann, A.; Ghanem, C.; Erhard, S. The Fragmented Picture of Social Care for Older People in German Prisons. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2023, 35, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch-Römer, C.; Wahl, H.W. Toward a More Comprehensive Concept of Successful Aging: Disability and Care Needs. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, L.F.; Buchanan, D. Successful aging: Considering non-biomedical constructs. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, M.; Berridge, C. Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Cohen, R.D. Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avieli, H. ‘A sense of purpose’: Older prisoners’ experiences of successful ageing behind bars. Eur. J. Criminol. 2022, 19, 1660–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, H.M.; Lozano, C.J.; Valdez, L.P.; Manzarate, R.; Lumawag, F.A.J. A grounded theory of successful aging among select incarcerated older Filipino women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 77, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik. Strafvollzugstatistik in Bayern. 2022. Available online: https://www.statistik.bayern.de/mam/produkte/veroffentlichungen/statistische_berichte/b6600c_202200.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, C.; Kenkmann, A. “Ich muss ständig beweisen, dass ich noch brauchbar bin”—Zur sozialen Lebenswirklichkeit älterer Menschen in Haft. Rechtspsychologie 2023, 9, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, A.; Le Mesurier, N.; Kingston, P. The mental health of older prisoners. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combalbert, N.; Ferrand, C.; Pennequin, V.; Keita, M.; Geffray, B. Mental disorders, perceived health and quality of life of older prisoners in France. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2017, 15, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geithner, L.; Wagner, M. Discrepancies between subjective importance and actual everyday practice among very old adults and the consequences for autonomy. Diskrepanzen zwischen subjektiver Bedeutung und tatsächlicher Alltagspraxis bei sehr alten Menschen und die Folgen für die Autonomie. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 54 (Suppl. 2), 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbs, J.J.; Jolley, J.M. Inmate-on-Inmate Victimization among Older Male Prisoners. Crime Delinq. 2007, 53, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, K.; Heathcote, L.; Senior, J.; Malik, B.; Meacock, R.; Perryman, K.; Tucker, S.; Domone, R.; Carr, M.; Hayes, H.; et al. Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Prisoners Aged over 50 Years in England and Wales: A Mixed-Methods Study; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin, L.I.L.; Colibaba, A.; Skinner, M.W.; Balfour, G.; Byrne, D.; Dieleman, C. Lost in transition? Community residential facility staff and stakeholder perspectives on previously incarcerated older adults’ transitions into long-term care. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, A.; Iliffe, S. Psychological approach to successful ageing predicts future quality of life in older adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, A.; Sharek, D.; Glacken, M. Building resilience in the face of adversity: Navigation processes used by older lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults living in Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3652–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M. How Positive Is Their Future? Assessing the Role of Optimism and Social Support in Understanding Mental Health Symptomatology among Homeless Adults. Stress Health 2017, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Osborne Association. The High Costs of Low Risk: The Crisis of America’s Aging Prison Population. 2018. Available online: https://www.osborneny.org/assets/files/Osborne_HighCostsofLowRisk.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Dünkel, F.; Harrendorf, S.; Geng, B.; Pruin, I.; Beresnatzki, P.; Treig, J. Vollzugsöffnende Maßnahmen und Entlassungsvorbereitung—Gesetzgebung und Praxis in den Bundesländern. Monatsschrift Kriminol. Strafrechtsreform 2024, 107, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilchling, M.; Wößner, G. Eingesperrt und Abgehängt? Gefangenentelefonie im Lichte des Resozialisierungsanspruchs, des Rechtlichen Rahmens und der Praxis im Ländervergleich; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).