Abstract

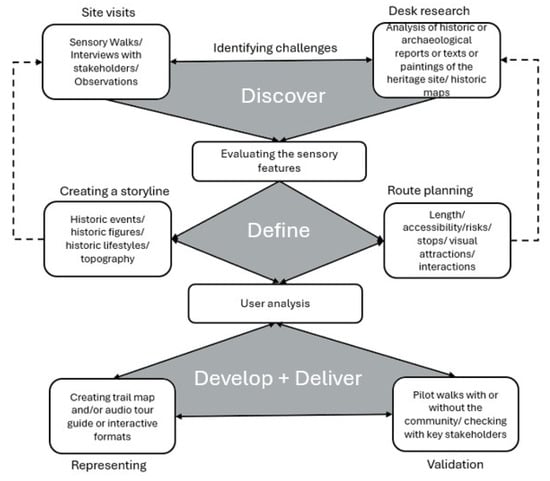

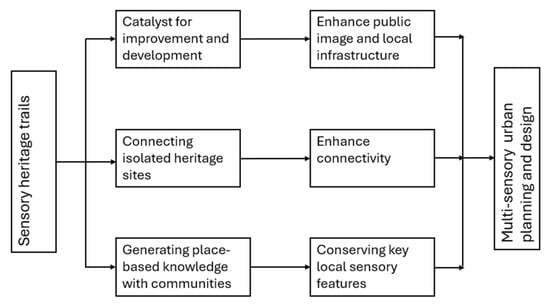

Trails in heritage sites are useful ways to engage visitors with the place. Sensory trails proposed in this paper, engaged with the sensory walking method, are designed purposefully to engage the multi-sensory features onsite with prompts to link to the historic sensory elements that have historic and cultural meanings to the heritage sites. Two questions are asked: (1) What process can we follow to design sensory heritage trails? (2) What criteria can be used to evaluate and guide the sensory features on site and from historic documentations? Taking design research as the overarching methodology, this paper reflects on the creation of two sensory trails, Sensing Beyond the Roundhouse and Sensing Around the Anglesey Column, following the Double Diamond framework developed by UK Design Council. An iterative design framework was developed, beginning with the identification of constraints and sensory opportunities through site observations, document analysis, and stakeholder interviews, which leads to interpretations of sensory features to shape storylines and route planning informed by user analysis. It is followed by representing the trails through sensory maps and other low-cost creative formats and then validating proposed trails with communities and stakeholders via pilot walks and feedback sessions. Four criteria are generated to assess sensory features based on engagement and authenticity: their contribution to the authentic historic atmosphere of the site; their ability to trigger imagination and evoke nostalgia; their distinctiveness and relevance to the site’s heritage narratives; and their capacity to encourage physical interaction and embodied engagement. The discussion part argues that sensory trails can be used as place-based strategies to inform urban planning and development around the heritage site through three pathways: catalyst for improvements and developments, connect isolated heritage sites, generate place-based knowledge.

1. Introduction

Trails and guided tours are popular in destination tourism, providing purposeful interpreted journeys for visitors to have a themed experience [1]. Guided heritage walks engaging with the senses are also becoming a popular and inclusive way to explore heritage sites and museums [2]. For example, Dulverton soundwalks is a guided audio tour inspired by the voices of past residents from within the Exmoor Oral History Archive. Sensory walks are commonly used in urban studies to understand the everyday living environment with a focus on one particular sense such as soundwalks, smellwalks, thermalwalks and lightwalks [3]. Soundwalk is a model that is explored by other sensory walks, and it emerged from the World Soundscape Project led by Schafer, who suggested exploration and evaluation of the surrounding environment by listening [4]. Applying sensory walking methods to museum and heritage sites could enrich sensory experience and bring a place to life for all visitors including those with sensory impairments [5]. However, despite growing interest, there is a lack of guidance on how to design sensory trails for heritage sites using a holistic, multi-sensory approach that bridges past and present. Existing sensory walking models tend to focus on an isolated sense or generate perceptual data on the surrounding environment, offering limited direction for integrating diverse sensory features into coherent heritage narratives and experiences.

Exploring ways to evaluate and design sensory features of heritage sites into trails and guided tours is timely to the shift in heritage practice moving beyond visual and material assets to explore the intangibles. In 2023, The UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council invested £1 million to rethink the role of senses in museums from accession, catalogue, curation of exhibitions, and visitor experiences. This renewed focus suggests a need to extend sensory approaches beyond museums to the wider heritage environment, developing inclusive and creative methods, such as sensory trails, that allow visitors to experience heritage in an embodied way beyond vision.

Addressing this gap, this paper draws on the experience of designing and implementing two sensory trails at small heritage sites in the UK to examine the design process and evaluation of sensory features for authenticity and engagement. The sensory trails proposed in this paper diverge from conventional heritage trails; rather than following predefined historical routes, they function as purposive cultural routes that connect nodes sharing similar pasts, narratives, or products related to the sites through engagement with the sensory heritage represented along the route. Situating sensory trails in the sensory heritage discourse, we aim to answer two questions: (1) What process can we follow to design sensory heritage trails? (2) What criteria can be used to evaluate more-than-visual sensory features on site and from historic documentations? Through answering the two questions, this paper offers a low-cost, non-interventional model for designing sensory heritage trails to evoke embodied and imaginative engagement with heritage sites. It highlights the potential of sensory trails in creating place-based spatial strategies around heritage sites.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

2.1. Sensory Heritage: From Perception to Representation

Recent scholarship positions sensory heritage as an emerging area within heritage and environmental studies. Research over the past decade increasingly recognizes the role of sensory experience in shaping heritage perceptions whilst remains underexplored both conceptually and methodologically [6]. There is a significant gap in understanding how cumulative sensory encounters are actually perceived and embodied on site [6,7]. There has been a bias towards vision over the other senses in the interpretation of knowledge, truth, and reality [8]. This bias reaches back to ancient Greece [9]. The French “sensory heritage law” to protect their natural heritage suggests the sounds of cows or the smell of pig sites are part of the patrimony of rural life, contributing to the ecology and materiality of the landscape [10]. A recent study looking at everyday living sites in Hong Kong defined sensory heritage as “the sum total of culturally valued sensorial experiences of a community—manifested as sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures—enabled through practices, rituals, and everyday activities, along with associated narratives and memories.” [7] (p. 19). They emphasized smells and sounds on site that have a long-term steady-state presence, produced as a result of various activities on site that hold cultural or collective significance to the community. They also highlighted the challenge of balancing subjectivity and inclusivity in determining what sensory elements merit preservation. Since their working context is everyday living spaces valued by the community, there is limited discussion on how histories or the past integrates with the sensory heritage making.

Documenting and representing sensory heritage are becoming popular in museums and heritage sites to engage visitors with the past, reinforcing the learning and understanding of our relationship with the heritage site [11]. Inviting people to touch objects offers a better sense of materials and creates a physical interaction with heritage sites [12]. Recreation of historic food is a common way to integrate taste experience into heritage sites that brings a sense of nostalgia and pleasure, attracting people to visit again [13]. Sound is often used to create spatial awareness and immersion though audio installations and audio walks restoring the historical acoustic environment [14]. Documenting heritage sounds, such as the Sonic Heritage project (2017), or recreating historical acoustic environments based on archival materials, such as the Soundscapes of the York Mystery Plays project (2016–2018), are at the heart of these sonic heritage projects that look at acoustic heritage or heritage soundscapes [15]. Other forms of aural cues, such as audio guides, oral histories, and musical performances, are used to give historical information [16]. Smells in heritage sites are often used to aid the visual cues to stimulate historic imaginations, which works effectively to drive visitors’ curiosities [17]. For example, Jorvik Viking Centre created the smells of Viking-age York. The re-invented smells by perfumers are the main approaches in current heritage and museum sector. In some cases, smell can work as a trigger for memory recall to create emotional connections with visitors of a shared past [18]. Findings from the Odeuropa project show that olfactory cues in exhibitions significantly enrich visitor experiences, with over 80% of participants reporting that smell made the experience more memorable and meaningful [19]. Despite such evidence, olfaction and touch remain under-researched in heritage contexts [6], often constrained by conservation concerns, health considerations, and practical limitations of implementation.

Sensory heritage may have institutional and practical challenges, especially when introducing ‘unpleasant’ sensory features back to the site, such as industrial smoke or sounds, that no longer exist or are ethically or environmentally problematic to reproduce [10]. For example, the Big Pit National Coal Museum in Wales, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, includes the infrastructure and landscapes of a working coal mine from 1880 to 1980. How are the smells and sounds of mine production valued by local people, particularly the current generation, who have minimal association with mines? How should they be part of the heritage and be presented to visitors? In what format should they be presented, as experiential, authentic, and non-harmful? Such questions underscore the need for further inquiry into how sensory heritage can be assessed, authenticated, and ethically represented in different contexts. This raises questions about authenticity, specifically, how much of an in situ sensory experience contributes to the aesthetic and heritage value of a place.

Authenticity in heritage conservation emphasizes the capability of objects, including architecture, that transmit the cultural significance of places such as form and design, materials and substances, use and functions, traditions and techniques, location and setting, and spirit and feeling [20,21]. In the sensory heritage context, discussion of authenticity emphasizes the interpretation process, rather than the physical substances. For example, in the discussion of olfactory heritage, authenticity of smells in heritage spaces could be considered as ‘an attribute to f the object, independent of the nose which smells it, a perception complement dependent on the smeller, or a communication between source and receptor, where meaning is created’ [17] (p. 4). In the discussion of sonic authenticity of soundtracks and music, authenticity is not always about realism but the materiality considering how and where it is made, how it is recorded and presented back to the audience, and supplementary comments from the audience [22]. These discussions shift from a material-based to a perceptual-based understanding of authenticity in understanding and making sensory heritage. For on-site experiences of heritage sites, the in situ experience or perceptions of sensory elements is critical to the sense of authenticity. Unlike mediated heritage experiences in museums, exhibitions, or digital reconstructions, the concept of in situ authenticity emphasises the multisensory, embodied, and situated nature of heritage engagement that is relational [23]. Sensory features presented and perceived on site can potentially create authenticity triggering that contribute to the perceived authenticity of the place. However, to what extent the sensory features on site reflect the cultural relevance of the past and how much intervention should be made to heritage sites to offer the authentic experience needs to be further explored.

2.2. Sensory Walking for Heritage Experience

Sensory walking is a useful method in ethnography enabling a situated understanding of how people perceive and experience the built environment. Through the integration of movement and multisensory perception, walking facilitates embodied interpretations of space where meaning is produced not solely through observation but through the bodily, temporal, and affective engagement with the place. Walking practices shape distinctive sensorial patterns of the city, “mediating the encounter between people and the sensory qualities of built environments.” [24] (p. 3278) In the context of heritage, walking thus provides a method for interpreting how the atmosphere, materiality, and sensory presence of sites contribute to cultural meaning [25].

Focused on the present experience of the local culture, Vasilikou explored participatory sensory walking in a heritage city in the UK–Canterbury. Three different walks were designed to engage communities with the landmarks of the historic core area where rich sensory elements were observed. Participants were asked to focus on interpretating the sensory qualities along the route and map them out afterwards. These walks focused on the presence and how the historic landmarks are experienced now and the sensorial qualities embedded to create the atmosphere. The author suggests there is a need to discuss the sensory assets of a place: “this generates a body of narratives of sensory heritage where the destination is an embodied experience, a path, a point of sensory interest in the traditional townscape.” [26] (p. 8). However, the extent to which these experiences contribute to interpreting historical meaning remains underexplored.

The imaginative dimension of sensory walks further enhances heritage interpretation. For example, situated listening is a form of speculative engagement with the site that can stimulate personal and sonic imagination [27]. Smells, closely associated with memories and emotions, can evoke imaginations even by looking at the source without the presence of the smells [28]. In the context of taste and flavor, imagination is stimulated through chemosensory mental imagery, influenced by expectations and predictions [29]. Sonic and olfactory cues in places could work as a catalyst for the brain to generate expectations, memories and associations, effectively combining the immediate, real world with possibilities and past experiences to create a richer spatial imagination [30]. In tourism contexts, heritage and cultural walks may deliberately invite visitors to see, smell, and taste at different historic spots [31]. Although such sensory engagements are often curated for entertainment or thematic purposes rather than grounded in historically authentic experiences, they nonetheless contribute to visitors’ learning and affective understanding of heritage sites. Low extends this analysis in the context of Singapore, observing that “even if such go-alongs may not be effectively realized, the various sensory descriptions of different trail spots would also serve as an avenue through which the experience of place in the city comes with sensory residues that reflect in embodied ways, the presence of social relations and group dynamics occurring in the urbanity.” [31] (p. 307). However, these curated sensory experiences also raise critical questions about authenticity and commodification in heritage interpretation. When sensory cues are selectively reconstructed or exaggerated to stimulate visitor engagement, they risk transforming heritage into a consumable spectacle rather than a lived, interpretive process.

2.3. Sensory Trails: From Embodied Experience to Imaginative Interpretations

The sensory trails proposed in this paper engage with the sensory walking method by being designed purposefully to engage with the sensory features on site. The features have prompts to link to the sensory elements that have historic and cultural meanings to the heritage sites. A trail, distinct from a simple route, is defined as “a visible linear pathway of many varieties, which is evident on the ground, and which may have at its roots an original and historic linear transport or travel function” [1] (p. 4). Trails are commonly communicated to visitors through formats such as printed, mobile applications, audio guides, etc. Their interpretive flexibility, combining material features with experiential and affective dimensions, can produce a deeper and more layered understanding of place [32]. Particularly for destination managers, trails are also useful tools for visitor management and place branding. The interpretive and emotional power of trails in heritage and cultural experiences of places cannot be underestimated [33]. A trail that encourages visitors to make connections between sites, landscapes, and other features of the journey enhances their experiences, being a transformational storytelling device.

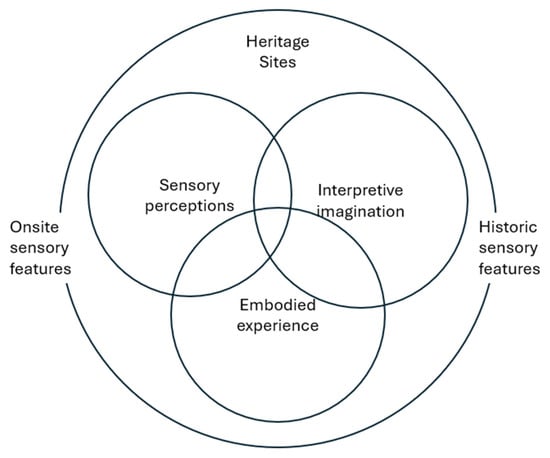

Embodiment through senses is central to the creation of meaningful encounters in sensory trails. Through sensory perceptions, embodied experience, and interpretive imaginations triggered by on-site sensory features or historic sensory prompts, sensory trails create a sense of belonging (see Figure 1), which is central to the cultural value of heritage and to fostering collective identity and empathy [1]. Research on guided heritage tours suggests that participation, hedonism, knowledge, and local culture and nostalgia are determinants of visitors’ experience of heritage sites [34]. Among these parameters, local culture and nostalgia are particularly connected to the sensory features of the site, recalling memories, and stimulating imaginations of the past.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of sensory trails facilitates the interplay between historic sensory features and on-site sensory features through sensory perceptions, embodied experience, and interpretive imagination. This framework is used in this paper to analyze the creation of two trails.

The challenge of creating sensory trails lies in balancing sensory stimulation with historical and cultural integrity, ensuring that sensory heritage experiences do not merely reproduce surface-level impressions but instead foster deeper, situated understandings of how the past is felt, remembered, and embodied in place. Cameron and Gatewood surveyed 225 people in Bethlehem and found that guided tours are among the desired essential features of historic sites. They found people care more about the authenticity and information richness provided on site as well as how they are connected to the site [35]. Most people visit historic sites primarily for information or education purposes, whilst others are looking for personal experience and pleasure. This suggests that sensory trails, by combining interpretation with embodied engagement, may offer a means to reconcile educational and affective dimensions of heritage experience. However, there is limited guidance on how to balance the on-site sensory features and historic pasts to produce an authentic, informative, and playful experience.

3. Materials and Methods

Using design research as the overarching methodological framework, this research adopts a reflective approach to investigate and develop a model for designing sensory trails at heritage sites. Design research positions the design practice as both the context and method of inquiry, using systematic reflection to generate transferable knowledge for future applications [36]. Within this framework, design is not only a creative activity but also a form of research through which insights emerge. The approach aligns with established principles of practice-based research [37,38], which recognize practice as a valid method of knowledge production. The process involves iterative cycles of appreciation, action, and reappreciation [39], where framing and reframing the problem is also part of the reflexive process [40]. Informed by the theory of ‘reflection in action’, a four-step iterative process is developed by UK Design Council starting with discovering the challenge and defining the problem that leads to the developing and delivering [41]. This framework provides a structured and flexible approach to design research by defining when and how research should be conducted across the four phases that can be used not only to guide the design process but also to assess the project [42]. A designer’s own knowledge and reflection are valid because design research aims to uncover the “knowing used” and the “knowing gained” during the design process. Since much of this knowledge is internal, tacit, and developed through the act of designing, the designer is often the only one who can articulate how their understanding shifts [36].

A series of questions can be asked to facilitate the reflections at each stage to ensure the process is valid [43]. For example, at the discover stage, key questions to ask for reflective designers could include the following: What are the constraints of the project? What problems are you solving? What are the needs of stakeholders and users? Through the retrospective reflection on creating two sensory trails (see Table 1), this paper aims to produce outcomes that extend beyond individual experience, offering a framework that can guide designers and heritage practitioners in developing inclusive, sensory-rich visitor experiences.

Table 1.

The reflective process on the design of sensory trails following the Double Diamond framework developed by UK Design Council.

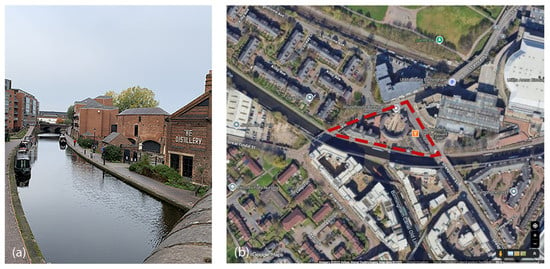

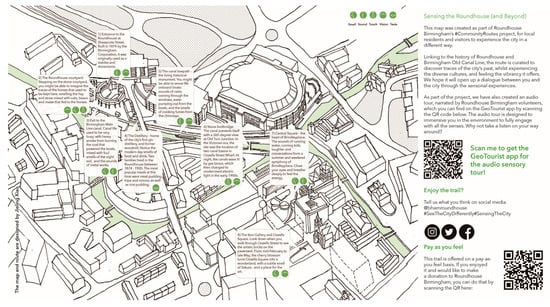

3.1. Initial Exploration Through the Roundhouse Trail

The Roundhouse Birmingham (RB) is a grade 2 listed crescent-shaped heritage building on Sheepcote Street Birmingham that reopened in 2019 (see Figure 2). The building, once used as a depot, is repurposed to have a restaurant, an exhibition space, a meeting space, and a distillery. It is at the quieter end of an old canal, a 10 m walk from the attractions around Brindley Place. The sensory trail was commissioned as one of their four community trails. It is presented through a map and an audio format via GeoTourist to allow self-guided walking following the trail. The audio tour was narrated by a local volunteer and used soundtracks of 19th century environmental sounds from the sound library created by the British Library to offer a historic atmosphere. The trail started from the gate of the Roundhouse, passing through the building, and moving onto the canal-side with a few surrounding attractions, including Birmingham Arena and Sealife Centre, the old Birmingham canal junction, and the Brindley Place clock tower (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(a) photo of the Roundhouse and (b) map showing the boundaries of the site.

Figure 3.

The Sensing Beyond the Roundhouse trail leaflet. The back of the leaflet is the blank map of the wider site inviting visitors to make their own sensory routes. © Jieling Xiao.

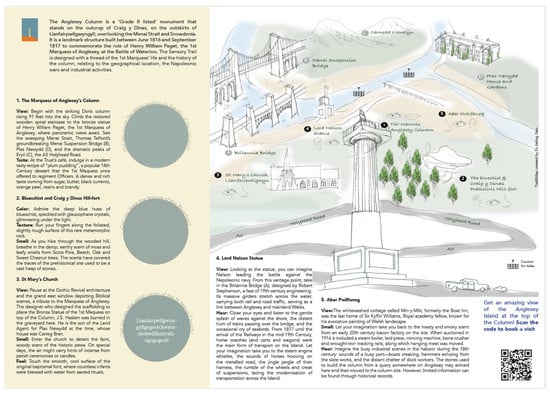

3.2. Further Exploration Through the Anglesey Column Trail

The Marquess of Anglesey’s Column (AC) is also a grade 2 listed heritage building, standing on the top of the UNESCO Site 13 Geopark Geomon, affording unrivalled panoramic views of Anglesey and Snowdonia (see Figure 4). The site’s entrance is hidden among a quiet residential area. Apart from the column, there is cottage building that has been turned into a café and an interpretation center to facilitate learning about the history of the Battle of Waterloo, where the Marquess fought courageously and lost his leg. The sensory trail was created as part of a research project funded by the UK prosperity fund with the main purpose of bringing more people to the site. The trail started with the column and then connected to the surrounding heritage places, which are also associated with the first Marquess (see Figure 5). The sensory features are derived from either historical documents or the site.

Figure 4.

(a) Photo of the Anglesey’s Column and (b) map showing the site boundaries. The site includes the Column, the café onsite, the car park and the trees in the woodland around the Column.

Figure 5.

The Sensing Around the Anglesey Column trail leaflet. The back of the leaflet is the key historical information of relevant figures, objects, and places associated with stops along the trail. © Jieling Xiao.

4. Results

4.1. Iterative Design Process

The design of the RB and AC sensory trails was an iterative, interdisciplinary process involving historians, site managers, creative directors, and community stakeholders (see Figure 6). It combined desk-based historical research, site visits, and participatory validation to translate limited archival information into engaging, multisensory experiences tailored to diverse visitor profiles. The process balanced historical accuracy with experiential engagement, adapting to the specific constraints and opportunities of each site.

Figure 6.

The design process of sensory trails summarized from the two trails.

4.1.1. Discover: Identifying Constraints and Sensory Opportunities

The extraction of historic sensory information is mainly from historic reports of the heritage sites, relevant paintings, and maps from Digmaps that may be related to important events and living culture involving sounds, smells, food, or drinks. As Low suggests that historical text describing sensory details in everyday life provides rich information on how social relations were; analyzing these texts provides necessary insights into how places are sensorially animated and experienced [31]. For example, in the AC case, the historic report contained limited details beyond commissioning and construction of the column, and the team relied heavily on the historic maps before returning to textual sources, leading to multiple exchanges with the historian to confirm accuracy.

On-site sensory features were explored through sensory walks with stakeholders focusing on sensory marks. Initial site assessments revealed key challenges, being small and away from the main road for visitors, that shaped the direction of both trails. For the AC site, additional constraints are identified including the small interior of the column and a 20-min visitor time limit inside the column.

4.1.2. Define: Interpreting Sensory Features to Shape the Narrative

This stage combines two parallel tasks: creating a storyline and planning possible routes for the trails. The key design problems raised from the site constraints are how to attract visitors to the site and create rich sensory heritage experience in the limited space. Looking at the surrounding sites and possible historical routes, the trails were created to connect both sites to their surroundings. It is common for urban-themed trails or tour circuits to link historic sites, buildings, and locations associated with an important period, a famous person, an architectural style, or a significant event [1]. For the RB trail, the storyline focused on the likely route of the horse carrying night soils along the canal during late 19th century Birmingham, revealing the sensory features of everyday life and the surrounding environment. For the AC trail, the storyline was created around the 1st Marquess and the history of the column, imagining a possible route where the stones used to build the column are transported. Drafted routes were developed with attention to length, accessibility, stops, visual attractions and interpretive opportunities linking onsite sensory features to historic narratives.

4.1.3. Develop and Deliver: Representing and Validating with Communities and Stakeholders

Due to the financial constraints, both trails are non-interventional, relying on hand-drawn illustrated map and prompts to evoke imaginations. Pilot walks with stakeholders and communities were used to test the trails, particularly how people engage with the sensory cues. For example, for the RB trail, the lead author conducted two guided tours with local communities during the heritage week of Birmingham in 2023 to validate the design of the trail and explored additional tools such as colored lenses to facilitate the experience. It revealed that historic features that no longer exist on the trail, such as industrial smoke, would require interpretive strategies to help visitors to imagine.

Visitor profiles influenced how both trails were developed and presented. The Roundhouse trail is aiming at local communities whose initial interest might not be the history of the site; the trail thus is created to focus on the lifestyle, boat living culture, and opportunities for interactions with the on-site sensory features. The Anglesey Column has a different landscape of visitors who are either interested in the geological features of the site, the Napoleonic Wars, or have family relationships to the history of the column. The trail in this case foregrounded historic sensory features and interpretive prompts to stimulate historic imaginaries.

4.2. Criteria to Evaluate Sensory Heritage Features

The criteria were derived from observations and reflections on the design iterations, comparing the patterns of on-site and historic sensory cues used in both trails. When analyzing the sensory features, apart from valuing the historic significance and relevance, the potential to create sensory encounters on site is also considered (see Table 2). The three-layered framework was developed from reading visitors’ experiences of Silves Castle and was adapted to guide the initial data analysis: elicited sense (what is the most outstanding and memorable experience), sensory details (sensory associations with the site), and triggers of sensory experiences (how the senses are activated to contribute to building the sense of authenticity) [43].

Table 2.

Examples of the more-than-visual sensory cues included in the two trails that capture the on-site and historic accents of the heritage site.

Four criteria arose inductively to guide evaluations of sensory features on site and from historic documentations that considers engagement and historical meanings.

4.2.1. Essential to the Historic Atmosphere (Historic)

One of the key criteria for evaluating historic sensory features is determining whether they constitute an essential component of the site’s historic scene or atmosphere. This involves assessing whether particular sensory elements, such as sounds, smells, textures, or visual cues, played a defining role in shaping how the site was experienced in its historical context (see Table 1). For instance, the rhythmic clanging of metalwork from the rolling mills along the canal near the Roundhouse would have been a distinctive and characteristic soundscape that conveyed both the industrial activity and social life of the area. Such sensory features are not merely incidental; they form part of the site’s intangible heritage, offering insight into the lived experiences and material culture of the past.

4.2.2. Trigger Imagination and Nostalgia (On Site and Historic)

The sensory features observed on site through sensory walking capture the in situ experience. However, as past activities and uses of heritage sites often significantly differ from their contemporary functions, the sensory cues on site may fail to correspond directly with the site’s historical references or inspirations. Creating a synergy between the on-site and historic sensory cues is critical. On-site and historic sensory features provoking a dialogue comparing the past and present should be included in the trail. For example, in the RB trail, living boats along the canal offer a good observation of the boat living lifestyle while contributing to narration of coal carried by boats moving between Wolverhampton and Birmingham during the 19th century, contrasting the sounds and smells. However, some distinct sensory features on site were deliberately excluded due to operational issues. For example, in the AC trail, the names calved on pole of the timber staircase inside the column could have been a nostalgic element to trace the visitors to the column in the past. It was excluded due to the limit of time that people can stay inside the column for safety and conservation purposes.

4.2.3. Distinctiveness and Relevance (On Site)

Incidental sensory features on site should be excluded, while distinct seasonal sensory features could be used to advise timings to take the trail and variations of the trial experiences. Sensory marks on site are often key features of the site that cannot be ignored [44]. However, not all sensory marks would match the storyline created for the trail. Incorporating sensory marks would need further evaluation whether it causes extra distractions on site or can accentuate the experience. For example, in the RB trail, the bell sound from the clock tower at Brindley Place enriches the historic atmosphere of the canal. Visitors are asked to start the walk from the Roundhouse at half past so that they will reach the bridge and be welcomed by the sound of the clock bell.

4.2.4. Encourage Physical Interaction and Engagement (On Site and Historic)

Some sensory features are selected to create physical interactions between the visitors and site. For example, in the AC trail, visitors are encouraged find and touch the blueschist in the woods at the foot of the column while appreciating the fact the surrounding trees did not exist when the column was firstly built. In the RB trail, visitors are encouraged to clap hands or sing while walking under the vaults of the brick bridge, imagining the busy crowded passing scene of boats during the industrial revolution times. This is possible because of the acoustics parameters of the vault space: the curvature surface creates diffuse reflections that make the clap feel immersive; the smooth brick surfaces absorb little high-frequency sound waves. Another example, in the AC trail, is a plum pudding recipe developed by a food artist in memory of the first Marquess to be experienced or collected at the café on site, enriching the experience of local culture. The trust decided to make it an on-site experience only to encourage visitors to come back. This has proved to be very popular and a source of income: as one batch is sold, another is being made.

4.2.5. Limitation of the Criteria

The criteria were developed based on two small heritage sites with well-documented histories and clear connections to wider historic events. The key purpose of these trails was to communicate these histories through a sensory heritage angle. This context may limit the broader applicability of the approach. For example, in highly transformed and gentrified environments where few materials or sensory traces of the past remain, the criteria may not be applicable. The two sites are small, thus they might not fully translate to larger or more complex heritage environments where sensory cues are more dispersed, fragmented, or contested.

5. Discussion

5.1. Sensory Heritage Trails as Place-Based Spatial Strategies

The two trails reviewed serve more than interpretive visitor routes and show the potential as place-based spatial strategies to engage with the surrounding environment, functioning as a place-based approach to document and present sensory heritage to the public. This aligns with MacLeod’s assertion that the trail space actively shapes visitors’ experiences [32]. Unlike conventional museum tours or traditional heritage trails, sensory trails operate as a way of knowing a place through both the present and the past, offering visitors a more immersive experience through sounds, smells, tastes, and textures. This orientation significantly differs from the technologically mediated sensory experiences, such as XR or immersive museum installations, which reconstruct sensory environments through digital augmentations that are often detached from the fluctuating, ecological, and lived conditions of a site [11]. The embodied approach in sensory trails bring to the foreground the contingent, situated, and ephemeral qualities of heritage sites that emphasize the ecological immediacy and the co-existence of tangible and intangible features in shaping heritage perceptions.

Cultural routes are often used as a strategy to plan and initiate improvements to an area to enhance its public image and boost a sense of place for local communities [1,25]. Some historical sites may also use trails as a strategy to develop the site. For example, the Archaeological Museum and Park Kalkriese created landscape interventions and pathways to represent the probable route of the Roman legions during the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. The spatial design in this case is intentionally following the visitor’s path to experience the heritage site.

However, the sensory trails presented in this article rely on minimal physical interventions to enhance the physical and experiential connectivity of heritage sites through walking. By organizing dispersed sensory nodes into a route with a historic storyline, the trails create mobility pathways that link otherwise isolated landmarks, enabling visitors to navigate through layered sensory meanings embedded in the landscape (see Figure 7). As Degen and Rose suggest, urban design and planning should move beyond the visual to analyze the sensual material life of objects and the affective forces generated when the material world greets the sensorial body [24]. Proactively activating sensory qualities of urban spaces can create richer opportunities for appreciation and engagement with the lived environment [45]. Non-interventional sensory trails may not provide as immersive a historical experience as interventional trails with restored historic features; it encourages visitors to establish their own connections with the site through the senses.

Figure 7.

A conceptual framework of sensory heritage trails as place-based spatial strategies to inform urban policies and design through three pathways.

Meanwhile, sensory trails also serve as valuable tools for generating place-based knowledge, offering insights into the unique qualities and identity of a site. This knowledge can then inform place-based planning strategies, guiding decisions about conservation, public access, and the design of new interventions in ways that are sensitive to the existing environment [46]. For example, identifying areas with distinct auditory or olfactory features might shape the placement of pathways, seating, or interpretive signage to enhance visitor experience without disrupting the site’s character. In this way, sensory trails not only enrich visitor engagement but also act as a research and planning tool, ensuring that development and management strategies are grounded in the lived, sensory realities of a place.

5.2. Community Engagement and Ethics in Creating Sensory Trails

We acknowledge one limitation in the development of the two sensory trails is the minimal engagement with local communities during the initial design stages. This imbalance between expert knowledge and community input raises ethical questions about whose heritage is being represented and whose voices are prioritized. While expert-led design can ensure technical and interpretive rigor, it risks producing trails that are detached from the lived experiences, memories, and values of the communities that inhabit these spaces [25]. Järviluoma, for instance, used participatory sensory memory walking to understand collective identities through sound, movement, and affect [47], revealing meaningful community engagement contributes to truthful remembering of the past and cultural intimacies. Heritage sites that have strong connections with memories of communities in such cases should definitely engage with the community at the very start of the design process to identify sensory features that are meaningful to them, as part of the sensory heritage. Sites that are quite disconnected from the community life may have room to discuss what is the best way to involve the community in the process.

The ethics of the sensory reconstruction of heritage sites, particularly involving physical interventions, requires community engagement from the start of the process. The French sensory heritage law, for example, has implications for a range of stakeholders when a country house is bought as a holiday home [10]. Tourists might be seeking peace and silence, but the law may also allow the noisy early-morning tractors. Another example is the revival of the smell of moss in Norway (a putrid smell), which is disliked by locals despite it being part of their heritage [43]. These cases raise issues of sensory justice, ownership of space, and the politics of whose perception counts in creating sensory trails.

Coordinating diverse perspectives can be time-consuming, and personal memories may conflict or contradict each other, making it difficult to create a coherent experience. Practical issues, such as accessibility, differing levels of interest, or cultural sensitivities, can also complicate collaboration [7]. Further research is needed to tackle these challenges, defining and providing participatory tools to assess different layers of sensory heritage experiences to guide the design and involvement of different stakeholders in designing sensory trails.

5.3. Challenges to Implement Sensory Heritage Trails

The development of a trail from a series of individual nodes (point attractions) to a functional trail requires the successful implementation of networks and social capital building [1]. The implementation requires the coordination of multiple stakeholders, including heritage organizations, local authorities, and community actors to ensure the trails are integrated into broader heritage networks and planning strategies [25]. This is particularly clear in the AC case, where trail implementation is contingent on woodland management plans and financial constraints. Moreover, the promotion and visibility of the trail need partnerships with nearby heritage sites to bring visitors to the column. Although the trails are designed for self-exploration, a few guided talks organized by the heritage organization will be useful to boost its visibility. Training volunteers or staff from the column to guide the trails and utilize the trails for seasonal activities also needs time and financial support to enable it to work effectively to engage with visitors [48]. These would demand institutional capacity, long-term commitment, and policy alignment.

Another challenge to implement sensory trails in multi-cultural and multi-lingual places is the accuracy and cultural sensitivity in translating sensory qualities to its diverse local groups. For example, in the AC case, translating the trail into Welsh will be the first step to implement it on site. This is because the Census (2001) found 1.7 million usual residents in Wales identified with a “Welsh” only identity (55.2% of the population) whose primary language is Welsh [49]. However, limited work can be found in sensory studies comparing descriptions of associated emotions and experiences between English and Welsh. Lessons can be learned from existing research in soundscape where researchers have identified challenges in translating English-based sensory narratives into other languages, suggesting subtleties of meaning, emotional resonance, or culturally specific associations may vary or be lost in the translation process [50]. Meanwhile, how smells and sounds are perceived is highly related to people’s social and racial positions, their familiarity with the space, and the media and political discourse about the place [51]. The embodied sensory experiences along the trails could cause issues around urban diversity and inclusivity if a single narrative is created without considering the multi-cultural demographics. Implementing sensory trails, thus, needs careful attention to translation and interpretation to assure meaningful community engagement and authentic sensory experiences.

Finally, the challenge also lies in sustaining sensory trails beyond their initial implementation, particularly within governance and conservation frameworks that remain predominantly focused on visual and material aspects of heritage. Integrating embodied, multisensory knowledge into spatial planning and decision making requires a significant shift in policy, institutional priorities, and professional practice [52]. Future research into impacts of sensory trails on visitors’ wellbeing and heritage understanding could potentially provide evidence to advocate for a change of attitudes towards conserving and representing meaningful sensory qualities of heritage sites in their practices.

6. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the discourse of sensory heritage by exploring sensory trails as a method to experience and represent sensory heritage. The central contribution is the applied design framework, which provides guidance to create sensory trails for heritage sites. There are two further contributions. The four criteria to evaluate sensory heritage features offers insights into evaluating sensory heritage based on the authenticity and the engagement potential. The conceptual framework of sensory heritage trails as place-based spatial strategies for urban planning and design through three pathways could inform approaches to integrate sensory heritage concept into urban policy and planning practice. The discussion highlights the importance of sensory justice in designing and implementing sensory trails, advocating for a sensitive and ethical approach.

However, this study also reveals limitations and challenges. Although the sensory trails proposed are low-cost and non-interventional, without sustained resources and stakeholder alignment, even well-designed trails could be underutilized. Future research should employ sensory ethnography or visitor analytics and other empirical methods to capture real-time bodily and emotional responses to sensory cues curated along the trail. Such data could help to validate the design framework and sensory elements that meaningfully shape visitor experiences, ensuring sensory trails move beyond design explorations towards evidence-based and visitor-responsive heritage practice. Additionally, a structured matrix of sensory cues linked explicitly to design objectives could enable designers to more systematically plan trails that align with interpretive goals, audience experience, and site-specific narratives. Such a matrix could not only enhance the effectiveness of sensory trails but also provide a critical tool for evaluating and refining trail design in ways that are responsive to both visitor experience and heritage storytelling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and M.B.; J.X. drafted the paper; M.B. reviewed and edited the draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ‘Sensing Around Anglesey Column’ trail is created with funding from The Skills and Innovation Voucher Scheme at the Bangor University (UK Shared Prosperity Fund) led by M.B. as part of The TRANSFORMATION Project (www.thetransformationproject.co.uk).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The two sensory trails and maps were created by J.X. with support from the Roundhouse Birmingham and the Anglesey Column Trust.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Tourism and Trails: Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, E.; Anand, S. Guided heritage walks as a tool for inclusive heritage education: Case study of New Delhi. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, A. A pocket guide to soundwalking: Some introductory notes on its origin, established methods and four experimental variations. In Stadtökonomie–Blickwinkel und Perspektiven: Ein Gemischtwarenladen/Perspectives on Urban Economics: A General Merchandise Store; TU Berlin University Press: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R.M. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, C.; Leemans, I.; Fleming, B. How can scents enhance the impact of guided museum tours? Towards an impact approach for olfactory museology. Senses Soc. 2022, 17, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.; Bond, J. Sensory and multisensory perception—Perspectives toward defining multisensory experience and heritage. J. Sens. Stud. 2024, 39, e12940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P.; Lam, L.H.; Kam, Y.C.; Yue, R. Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, D.M. (Ed.) Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bendix, R. Life itself: An essay on the sensory and the (potential) end of heritage making. Traditiones 2021, 50, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Doucé, L.; Nys, K. Multisensory museum experience: An integrative view and future research directions. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, C. Touch in the Museum. In The Book of Touch; Classen, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J. Creating memorable experiences in a reuse heritage site. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T. Memoryscape: How audio walks can deepen our sense of place by integrating art, oral history and cultural geography. Geogr. Compass 2007, 1, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.J. Sonic Pasts: Acoustical Heritage and Historical Soundscapes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.M. (Ed.) Hearing History: A Reader; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bembibre, C.; Strlič, M. Smell of heritage: A framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembibre, C.; Strlič, M. From smelly buildings to the scented past: An overview of olfactory heritage. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 718287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, S.C.; Leemans, I.; Bembibre, C.; Tullett, W.; Verbeek, C.; Alexopoulos, G.; Marx, L.; Michel, V. The Olfactory Storytelling Toolkit: A “How-To” Guide for Working with Smells in Museums and Heritage Institutions. Odeuropa. 2023. Available online: https://odeuropa.eu/the-olfactory-storytelling-toolkit/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Assi, E. Searching for the concept of authenticity: Implementation guidelines. J. Archit. Conserv. 2000, 6(3), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Xiao, J. Dynamic authenticity: Understanding and conserving Mosuo dwellings in China in transitions. Sustainability 2020, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, N. The Celtic Tiger ‘Unplugged’: DV realism, liveness, and sonic authenticity in Once (2007). Soundtrack 2014, 7, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly, J.; Canavan, B. The emergence of authenticity: Phases of tourist experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 109, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, M.M.; Rose, G. The sensory experiencing of urban design: The role of walking and perceptual memory. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 3271–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.W. Heritage trails and tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilikou, C. Multi-sensory navigation in a heritage city: Walking atmospheres of community well-being in Canterbury. J. Biourban. 2019, 7, 13–24. Available online: https://journalofbiourbanism.org/2019/01/19/jbu-volume-vii-1-2018/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Chung, W.M.; Tsai, W.C.; Liang, R.H.; Liu, M.; Kong, B.; Huang, Y.; Chang, F.C. Soundscape fiction: Designing and situating sonic design fiction to stimulate the imagination. Digit. Creat. 2025, 36, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P.; Liew, K. Real and imagined smellscapes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C. ‘Tasting imagination’: What role chemosensory mental imagery in multisensory flavour perception? Multisensory Res. 2022, 36, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Lindborg, P. Spatializing Sensory Memory Through Sketching and Making. In The Senses and Memory; Dupuis, C., Ed.; Vernon Press: Wilmington, NC, USA, 2025; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Low, K.E. The sensuous city: Sensory methodologies in urban ethnographic research. Ethnography 2015, 16, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, N. The role of trails in the creation of tourist space. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.P. Alternate routes: Interpretive trails, resistance, and the view from East Jerusalem. J. Community Archaeol. Herit. 2015, 2, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M. Satisfying experiences: Guided tours at cultural heritage sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C.M.; Gatewood, J.B. Excursions into the un-remembered past: What people want from visits to historical sites. Public Hist. 2000, 22, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downton, P. Design Research; RMIT Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lunenfeld, P. Design Research: Methods and Perspectives; MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.; Malins, J. Visualizing Research: A Guide to the Research Process in Art and Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W. Schön: Design as a reflective practice. Collection 2010, 21–25. Available online: https://inria.hal.science/inria-00604634v1 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Design Council. The Double Diamond. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Kochanowska, M.; Gagliardi, W.R. The double diamond model: In pursuit of simplicity and flexibility. In Perspectives on Design II: Research, Education and Practice; Raposo, D., Neves, J., Silva, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 16, pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, J.; Andersen, B. Remembering and reconfiguring industrial heritage: The case of the digester in Moss, Norway. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; Cunliffe, A. The dent in the floor: Ecological knowing in the skillful performance of work. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 61, 1766–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, A.; Xiao, J. Proactive Sensory Urban Design. Urban Des. Group J. 2023, 165, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana Vigiola, G. Understanding place in place-based planning: From space-to people-centred approaches. Land 2022, 11, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järviluoma, H. The art and science of sensory memory walking. In The Routledge Companion to Sounding Art; Cobussen, M., Meelberg, V., Truax, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Black, R.; Ham, S. Improving the quality of tour guiding: Towards a model for tour guide certification. J. Ecotourism 2005, 4, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census 2021. Ethnic Group, National Identity, Language and Religion in Wales. Welsh Government. Available online: https://www.gov.wales/ethnic-group-national-identity-language-and-religion-wales-census-2021-html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Aletta, F.; Oberman, T.; Axelsson, Ö.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lau, S.K.; Tang, S.K.; Jambrošić, K.; De Coensel, B.; Van den Bosch, K.; et al. Soundscape assessment: Towards a validated translation of perceptual attributes in different languages. In Inter-noise and Noise-Con Congress and Conference Proceedings; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 261, pp. 3137–3146. [Google Scholar]

- Barwick-Gross, C.; Chollet, J.; Kulz, C. Researching urban diversity and the (re-) production of whiteness: Reflections on the purchase and challenges of sensory methods. Front. Sociol. 2025, 10, 1512271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibaud, J.-P. Sensing the City: Empirical Perspectives on Urban Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.