Abstract

Josip Vojnović (Omiš, 1929–Split, 2008) is a prominent Croatian architect, primarily known in professional circles for organising the construction of Split 3, the expansion of Split during the 1970s. His professional career began with the design of primarily residential buildings and concluded with his position as a university professor. This article analyses the URBS 1 standard residential buildings constructed during the 1960s, which were intended to address the housing shortage in post-war Split. These buildings—the most notable part of Vojnović’s design work—were built in several locations throughout Dalmatia. Even at the time of their construction, they were recognised as a significant example of designed and executed standardised residential architecture. This research is based on archival materials from the State Archives in Split, the Archive of the Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia–Split, as well as research in situ. The article examines the design of the standard building, including a functional analysis of the residential unit and all the floors, as well as a formal and compositional analysis of the façade. The URBS-1 buildings are an illustrative example of housing construction, due to their number, distribution and architectural features shaped by the economic, technological, social and cultural context of the time.

1. Introduction

The work of Croatian architect Josip Vojnović (Omiš, 1929–Split, 2008) is closely linked to the functionalism of the 1950s and 1960s. His residential buildings were built in Dalmatia, mostly in Split. During his professional career, he worked as a designer, mainly of residential buildings, and was involved in the planning and organisation of the construction of the Split 2 residential complex. He was also involved in organising the construction of Split 3—a large expansion of the city to the east. He ended his career as a university professor at the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Split.

The most prominent part of his design work is collective housing, i.e., the design of the URBS 1 residential buildings. These buildings, or rather the apartments, are the topic of this article for several reasons. Even at the time of its construction, the standard URBS 1 building was accepted as an appropriate example of a residential building in Split.

Compared to other typical solutions by other architects from the same period, the URBS 1-type buildings stand out for the multiple repetition of their design. Given that they were built in several residential areas, and in one case even between buildings within the existing city structure, Vojnović’s residential buildings are a significant and illustrative example of housing construction in Split. The floor plan organisation of the URBS 1 buildings influenced the design solutions of many similar buildings (with a “boxy” volume). They are characterised by a structural system with transverse load-bearing walls, longer non-load-bearing façades opened with loggias or glass walls, and apartments of bilateral orientation. Such buildings marked an entire decade of housing construction in Split, and variants of the URBS 1 apartments have been used, as architect Darovan Tušek stated in 1996, for even longer, up to the present day [1] (p. 83).

Despite all of the above, a scientific analysis and evaluation of the typical URBS 1 residential building have not been systematically carried out to date. These buildings, as well as their author, Josip Vojnović, are indispensable when it comes to studying the development of Split in the 1960s in lexicographic terms [2] (p. 30), [3] (pp. 19–21), [4] (pp. 201, 206–207), [1] (pp. 26, 83, 86, 116, 125–126, 163–164, 169, 171–173, 176, 181–183, 188, 196, 198, 200, 211–212, 218, 222, 235, 249, 281, 348, 392, 428, 447, 459–460, 499, 502–504, 506–508, 510–511, 514–515, 521), [5] (pp. 78–79), [6] (pp. 12, 14, 34, 36, 38, 95, 163–164, 191, 197, 339, 351–352, 355–356, 362), [7] (pp. 393–401) and thematic publications [8] (p. 34), [9] (p. 75), [10].

This article analyses the design and application of the typical URBS 1 residential building and apartment in Split. In the period from 1960 to 1967, thirteen such buildings were built in three residential areas, and one building was interpolated into the existing urban fabric. The article examines the design of the standard building, covers a functional analysis of a typical apartment, as well as of all the floors, and includes a form–composition analysis of the standard façade.

2. Professional Background of Architect Josip Vojnović

Josip Vojnović was born in the small town of Omiš near Split in 1929 and died in Split in 2008. He studied at the Department of Architecture of the Faculty of Technology in Zagreb and graduated from there in 1954. After his studies, he lived in Split, where he worked in various architectural jobs. Vojnović’s life is marked by three significantly different, yet logically connected and often intertwined parts of his professional career. At the beginning, after completing his studies, he worked as a designer at the construction company “I. L. Lavčević” from Split. He then took a job at the Urban Planning Bureau–Split, where he worked in the Housing Construction Administration. In this stage of his career, he was working on optimising production costs and processes in relation to the quantity as well as quality of executed buildings, which at that time was covered by the label of rationalisation. In addition to designing buildings, over the next period of almost twenty years, he was involved in organising the construction of residential complexes in Split. In 1959, he was employed at the Bureau for Housing Construction, and then in 1960 at the Municipal Fund for Housing Construction. From 1966 to 1982, he worked at the Split Construction Enterprise (later the Split Construction Institute) [11,12,13]. Throughout his career, he completed almost a hundred mostly residential buildings in Split, Omiš, Šibenik and other towns in Dalmatia. The pinnacle of his ability to manage, organise and implement construction was the large urban area of Split 3—a city expansion project during the 1970s on the eastern part of the Split peninsula, intended for 50,000 inhabitants. In 1976, Josip Vojnović received the City of Split Award for the successful management of the entire Split 3 project [7,11,12].

His vast experience in designing residential buildings, as well as work on the organisation and implementation of residential buildings and whole settlements, encouraged architect Vojnović to try his hand at scientific research on the matter. He systematised and scientifically processed the various data he had at his disposal, and in 1978 he received his doctorate from the Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb with the topic of his doctoral dissertation being “Rationalisation and Evolution of Housing and Communal Construction in the Processes of Planning, Organization and Programming” (mentor Prof. PhD Božidar Rašica) [14]. In 1982 he was employed at the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Split, where he worked at the Department of Building Construction as a full professor until his retirement in 1999. During his work at the faculty, in addition to teaching, he was engaged in research into building physics and reviewed the project documentation for this area.

3. Mass Housing Development in Europe in 1950s and 1960s

At the end of World War II, much of Europe was in ruins. Parallel to the post-war reconstruction of existing infrastructure, a period of intensive industrialisation began, which resulted in migrations from the rural areas to the cities. The post-war period was, therefore, characterised by a significant shortage of housing units, both in the capitalist countries and in the communist ones—the two opposing types of state organisation in post-war Europe. In both cases, this shortage was addressed through indirect state intervention, which resulted in the construction of mass housing estates [15] (pp. 81–86), [16] (pp. 7–9). For this purpose, Western European countries mainly established state-supported organisations: public agencies (e.g., France), social housing companies (e.g., the Netherlands, Austria, Germany) or cooperatives (e.g., Scandinavia). Although communist countries promoted centralised planning, mass housing construction was mediated by different organisational structures indirectly supported by the state, such as industrial enterprises, social enterprises and cooperatives. These were in many ways equivalent to those in Western Europe [15] (pp. 81–86). Post-war mass housing construction rested on the foundations of the CIAM (Congrès internationaux d’architecture modern, held periodically from 1928 to 1959), both in terms of the floor plan layout and overall design of residential buildings and in terms of the urban planning of areas [17]. One of the major ideas of the CIAM was to improve the hygiene conditions for all residents. The spatially minimal individual housing unit that provides high-quality insolation and ventilation became the basic unit for larger facilities, individual buildings or even entire settlements. To achieve equal quality for all units, the perimeter urban block pattern was abandoned, and the new Zeilenbau pattern was adopted instead. The orientation of the longitudinal axis of the rectangular slabs was mainly north–south. Widely spaced linear blocks of apartment buildings with a large number of units allowed for the land to be reserved for greenery and communication [18]. In addition to the architectural and planning principles of the CIAM, by applying standardisation, rationalisation and the use of prefabricated elements during construction, post-war mass housing developments also followed the principles of economic efficiency outlined by the same organisation [19] (pp. 269–270).

Mass housing construction in Croatia and in Split took place in a similar manner to that described above. Croatia was, from 1918, a part of the former Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1945, after the end of World War II, the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia was proclaimed, with Croatia as one of six constituent republics, as a legal successor to the previous kingdom. The established country was led firmly by a one-party communist government headed by President Josip Broz Tito. For the first few years of its existence immediately after the war, Yugoslavia belonged to the Eastern Bloc. However, in 1948 after breaking ties with the USSR, it became politically independent but was subject to economic sanctions from said bloc. In response, it began to rely on Western aid, which partly enabled the country’s post-war modernization and reconstruction. Yugoslavia was a federation of six republics and two autonomous provinces but was ruled by a strong central government under the control of the Communist Party. Yet, the problem of extensive rural-to-urban migration and consequent shortage of housing units was being solved by decentralised local housing organisations that were able to act autonomously within the self-management system [15] (p. 342–376). The right to housing was one of the important determinants of socialism, although in its implementation it was more accessible to some social and political strata. The beginning of mass construction, from 1945 to 1955, was marked by financing from the state budget, but the management of the housing stock was carried out by local authorities. From 1955 to 1960, state and municipal social funds were introduced to grant loans for housing construction. Special organisations were established, which had the functions of investment for contractors and distribution for users. From 1960 to 1965, elements of a market economy were gradually being introduced into housing policy. From 1965 to 1975, municipal funds were abolished, and their role was taken over by local banks. At this stage, construction companies took on the role of producing apartments for the market. In addition to companies buying apartments for their employees, individual buyers were also coming forward. The market approach resulted in apartments of insufficient quality, and from 1971, social management of housing construction was introduced (DUSI “Društveno upravljanje stambenom izgradnjom”). The function of construction organisation was taken over by special organisations (SIZ “Samoupravna interesna zajednica”) [20] (pp. 342–343), [21]. The ownership of the apartments in former Yugoslavia was social, while the users were paying symbolic rent. With the introduction of the democratic system in the 1990s, apartment users were given the opportunity to purchase apartments at preferential prices, far below the market value. By the beginning of the 21st century, most of the apartments in Croatia were owned privately.

Standardised mass housing estates built in Western Europe between 1945 and 1975 and in Eastern Europe between 1950 and 1985 [22] are often facing many problems at the beginning of the 21st century. Some of them have deteriorated significantly due to change in demographic structure, undeveloped transportation infrastructure, poor environmental quality, noise, lack of safety or lack of community involvement. In some cases, problems arise because of poor construction quality. Also, the apartments in these estates were originally designed to meet the needs of middle-class or affluent working-class families. They were often designed to meet minimal spatial standards. Thus, their role in the contemporary housing market is unclear, usually serving just as a temporary solution. And finally, large housing estates, once constructed and maintained with public funds, nowadays face private ownership, which often does not possess the culture, knowledge and understanding of the design unity of the estate, which easily leads to eclectic adaptations [16].

4. Materials and Methods

For the purposes of the research, archival materials from the State Archives in Split, Archives of the Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia–Split were used [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

In the archive, drafts (floor plans, sections, façades) on tracing paper have been partially preserved. These served as templates for reproducing the required number of sheets for the graphic part of the main building project necessary to obtain a building permit. The textual part of the main project, including the technical description, has not been preserved in the archive. For buildings no. 6 and 14 in Split and buildings no. 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 in Šibenik, the drafts have not been preserved. For the other analysed buildings, a certain number of drafts have survived, and for some buildings, only a single draft exists. Therefore, it is very important that the complete conceptual design of the URBS 1 building has been preserved. By analysing this “zero” project, comparing it with the preserved drafts, and conducting in situ inspection and analysis of each building, it was possible to supplement, that is, reconstruct, the project documentation and to reveal Vojnović’s design logic and his approach to planning in this specific location. Such “supplemented” material, created by using Autodesk AutoCAD 2023 software, constitutes an important main contribution of this study, as previously unpublished designs for the URBS 1 buildings have now been published.

The buildings have also been analysed in situ from February to November 2025. For each building in Split, an average of three sessions were conducted, while for the buildings in Šibenik, Omiš, and Ploče, one session was carried out after familiarisation with the examples in Split. The buildings were analysed on-site through visual observation and necessary measurements. Special attention was given to access paths and staircases, as the connection of the buildings to the ground was often unresolved in the preserved drafts. By studying the available archival material and analysing the buildings in situ, certain deviations during construction were identified. For example, buildings no. 12 and 13 are shorter in length than in the design. For buildings no. 9 and 13, parts of the segmented floor plan differ from the project. Buildings no. 11, 12 and 7 were designed with five above-ground floors, but were actually constructed with six. In addition, closures of loggias on the southern façades and improperly executed façade restorations were observed.

5. Rational Residential Buildings Type URBS 1

After World War II, Split became the cultural, economic and administrative centre of Central Dalmatia. As a result, its population started to grow rapidly due to the immigration of people from the surrounding areas. Since the city had the function of a military port, this also entailed the immigration of military personnel from other parts of Yugoslavia at the time. In 1951, Split adopted the Directive Regulation Basis of the City of Split, which determined the network of city roads that demarcates residential areas [1] (p. 105), [35]. According to the CIAM’s guidelines, urban planning regulations for residential settlements were drawn up in the 1960s, and the settlements themselves were constructed by the end of the same decade.

In the late 1950s, the housing crisis in Split reached its peak. In 1948 Split had a population of 48.949, which by 1961 grew to 78.792 and in 1971 to 163.762 [36] (pp. 7, 9). The large increase in the population was not accompanied by the construction of an adequate number of new apartments. The Split municipality sought to solve the problem by building as many apartments as possible in the shortest possible time. In 1957, it invited architects to propose a solution for an apartment whose design could be repeatedly applied when constructing residential buildings in new residential areas of Split. The municipality required that the apartment be designed for a family of four and have a bilateral north–south orientation. By arranging these typical apartment units, buildings with a long axis in the east–west direction and entrances from the south or north side would be formed. The buildings were planned to be five-storey, and the basement to be used to accommodate woodsheds with the possibility of being converted into a wartime shelter. A large number of architects responded to the call with one or more proposals [1] (pp. 80–87). Among them was architect Josip Vojnović from the Urban Planning Bureau-Split, who in 1958 offered a standard two-bedroom apartment for a family of four called URBS 1, which fully met the requirements of the municipal call [23,24].

5.1. Typical Housing Unit

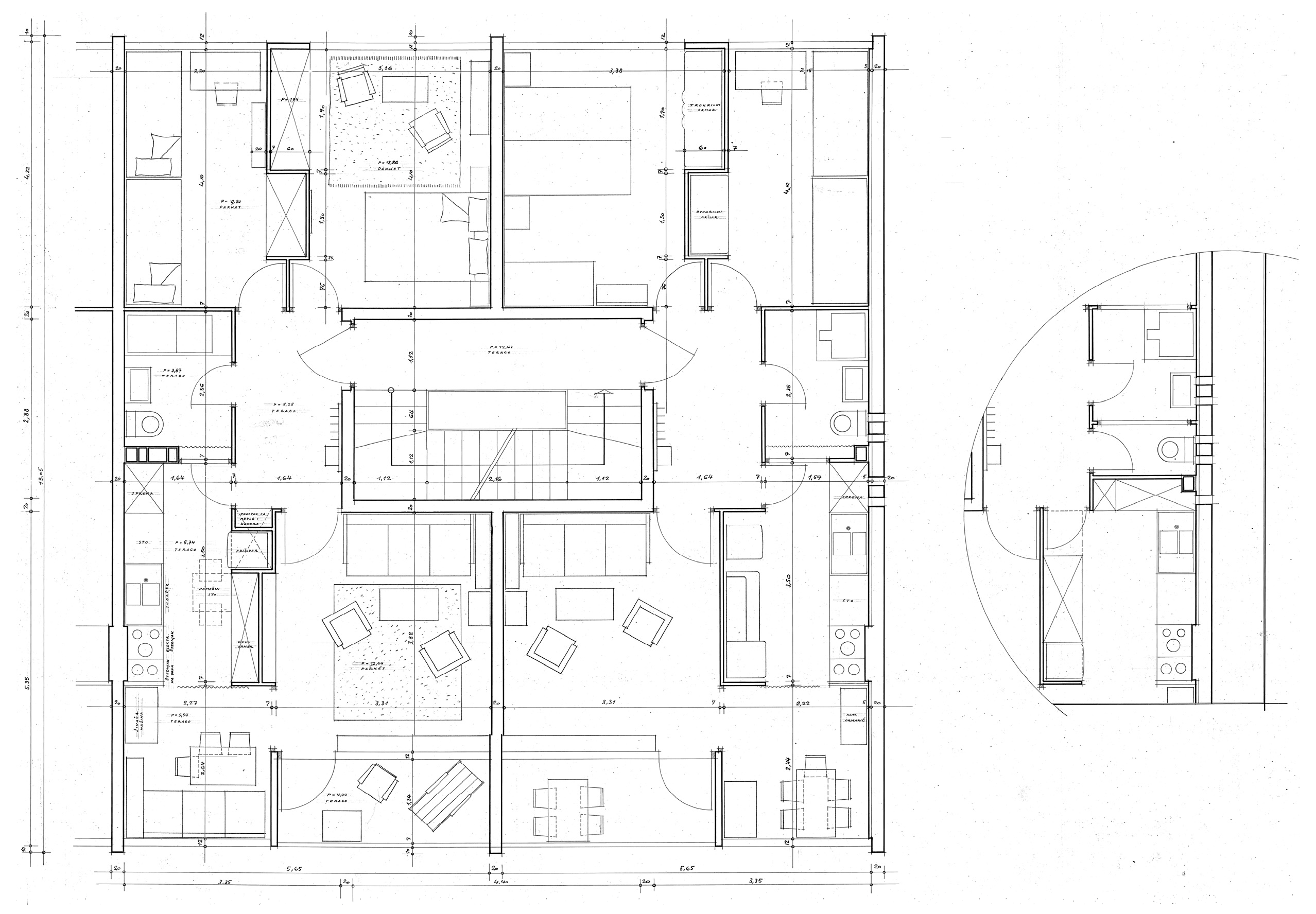

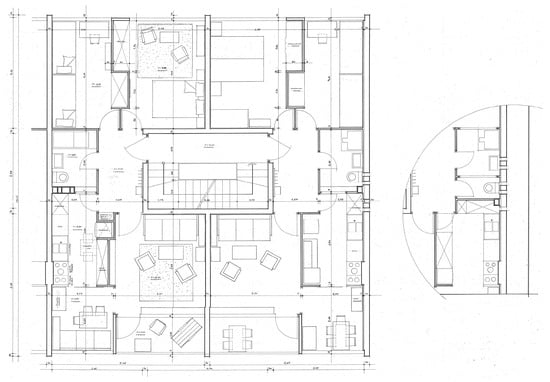

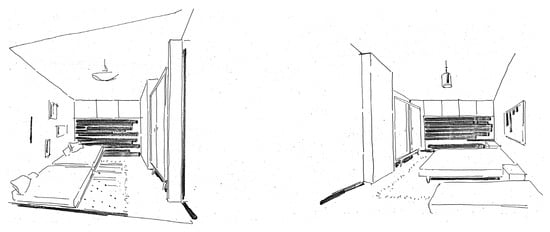

The floor plan of the apartment is functional. It is accessed from the middle of the floor plan, and all the rooms of the apartment can be entered directly from the entrance area. In the northern part of the apartment, there are two bedrooms, and in the southern part, there is a kitchen with a dining room and a living room with access to the loggia. The bathroom occupies the central part of the floor plan and is the only room in the apartment without direct ventilation and sunlight. There are no load-bearing walls inside the apartment, and the rooms are divided by partition walls (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

A typical floor plan from the 1st to the 4th floor of the URBS 1 apartment, with the bathroom layout variant on the right. Source: Ref. [23].

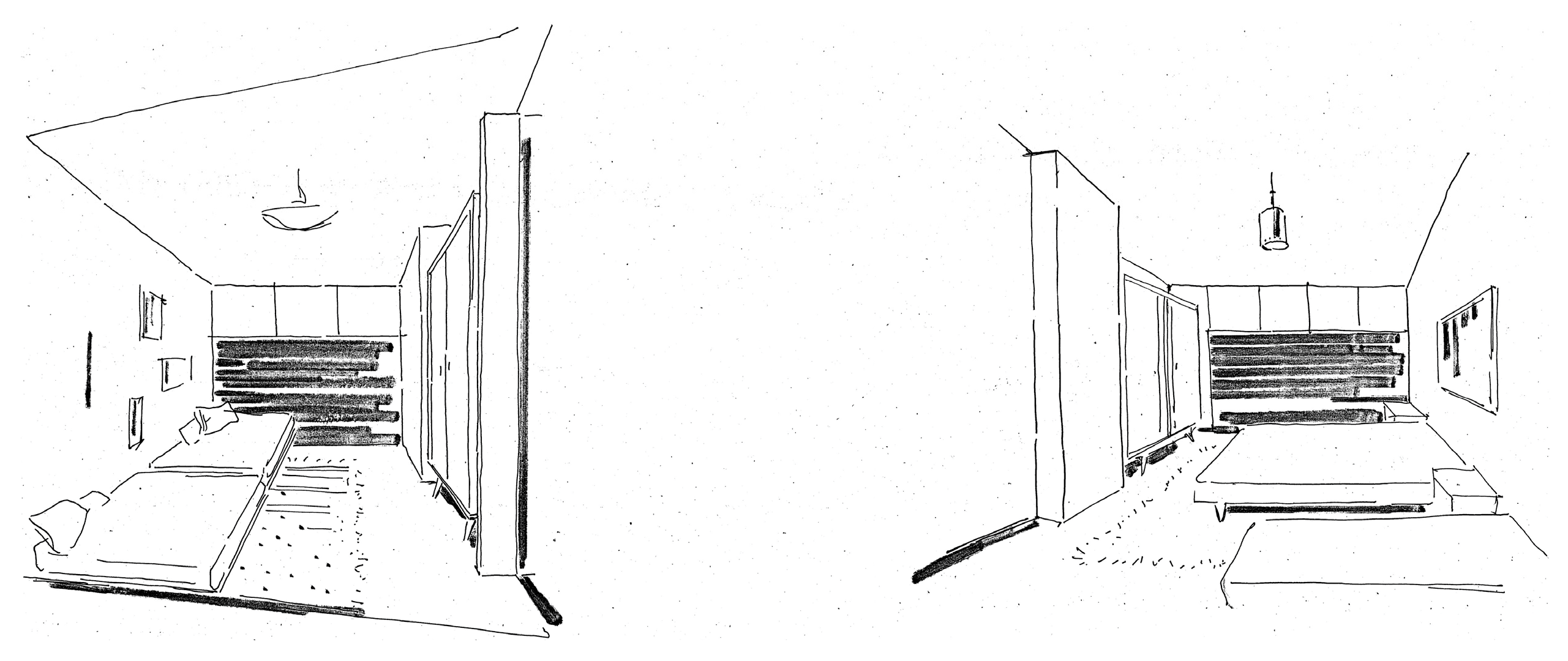

Figure 2.

Interior of the children’s bedroom and the parents’ bedroom. Source: Ref. [23].

Figure 3.

Interior of the living room, kitchen, and dining room. Source: Ref. [23].

At the time of the design and construction of standardised buildings, a large number of articles on the subject were published in the daily newspapers and professional press [37,38] (pp. 72–73), [39] (pp. 104–108), [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Among them, the article entitled Housing Situation in Split/Current State, Opportunities and Paths to Resolution, by economist Drago Sumić and architect Lovro Perković, stood out [40]. The authors analysed the factors that optimise the construction of standardised buildings. In their opinion, these factors arose as a result of good decisions made during the urban design of residential areas, which consequently had an impact on the architectural designs of the buildings. In the times before 1958, which preceded the publication of the article, the authors stated that the locations of buildings in Split were chosen without prior analysis—intuitively. They explained their position: “Since the complete urban design solution with all the communal facilities of a residential neighborhood is financed from the funds for housing construction, it is already required today that the apartment be treated not only as a part of the building, but as part of the urban solution, as a unit of a residential neighbourhood. Therefore, in the future, all financial and technical issues should be coordinated precisely in terms of the most favorable final result of an urbanistically designed whole” [40] (p. 123). They pointed out that the shape of the building’s floor plan is a very important factor in savings. Sumić and Perković argued that, by analysing several construction institutes in different countries, it was determined that “for the same construction area, savings can be achieved with the shape of the floor plan alone”. A smaller width of the street front and a deeper building floor plan result in a smaller volume of walls and less work on the building’s façade. “Good and proper orientation and insolation are also important elements of good and economical housing”, and concluded that a southern orientation is the most favourable for Split’s conditions [40] (p. 125). “The apartment must be treated as a workspace.” Practicality and rational use of time should be taken into account when designing apartments, and outdated concepts of living space should be replaced with new, contemporary solutions. The furnishings in the apartment should be modern instead of massive wooden furniture with large dimensions. The rooms should be of minimal size, but with a view of the external spaces of the surrounding nature. They also emphasised the importance of purposeful solutions for shading and protection of the southern façade from the sun. They advocated for the construction of loggias instead of large windows because they considered loggias to be a better solution in terms of protection from wind and sun [40] (p. 126). Architects should devote great attention to the design of building façades, because “inhabiting a beautiful environment is a fundamental prerequisite for good and pleasant living,” as Perković and Sumić pointed out. “The façade should not be treated in a formalistic manner, with non-functional elements created merely for effect; instead, it should be a rational expression of a better way of living, with visible elements of residential comfort. In doing so, we achieve both a pleasant appearance and an architecture with a sense of joy in living” [40] (p. 127) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Design requirements for residential buildings according to Sumić and Perković [40].

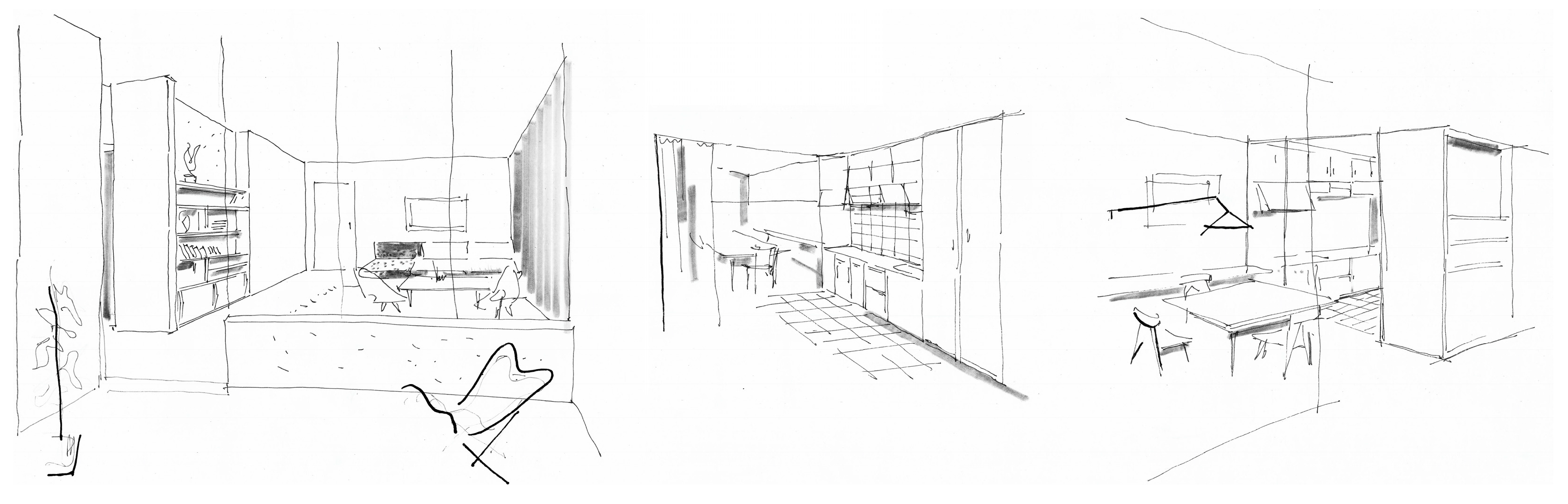

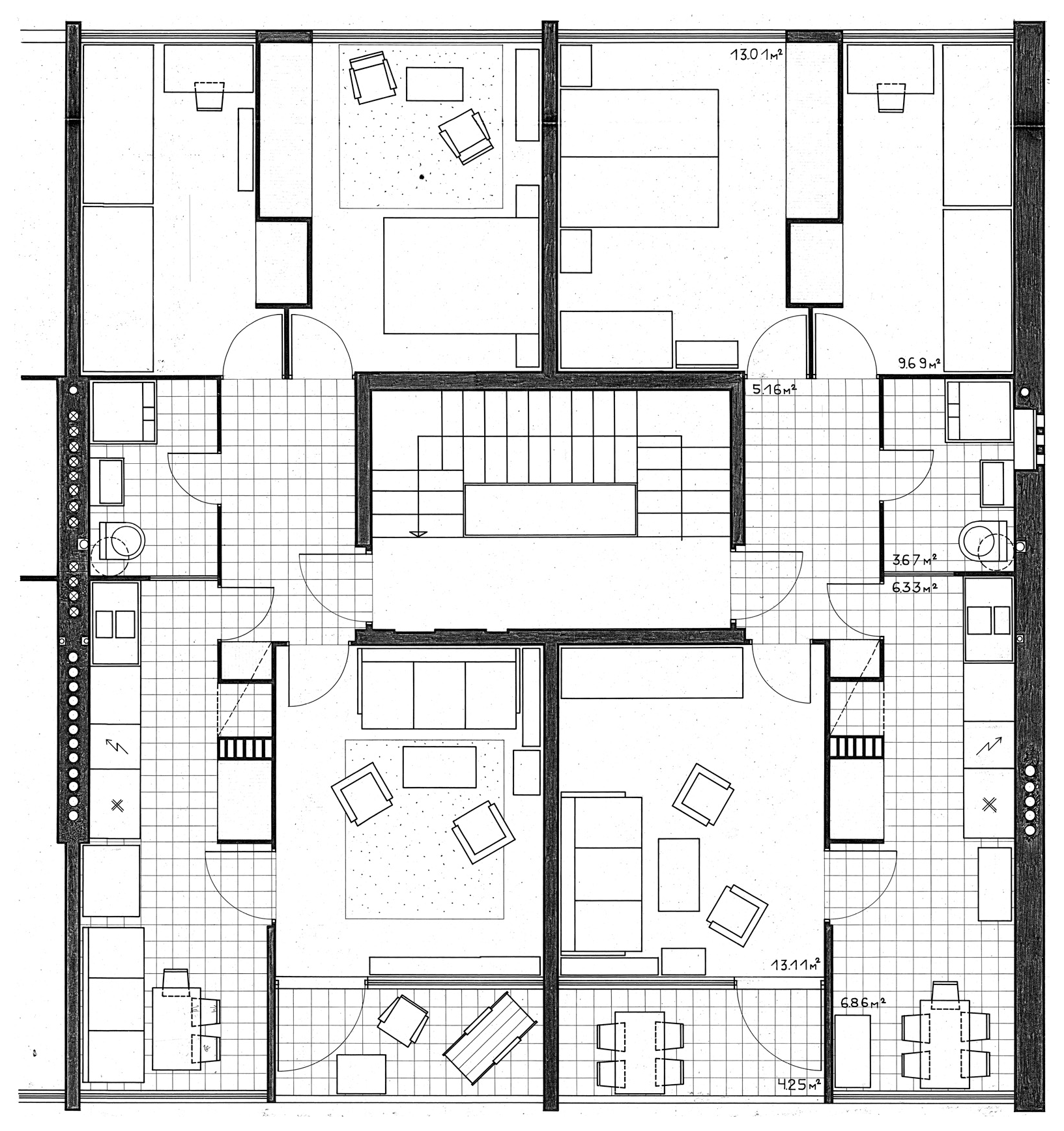

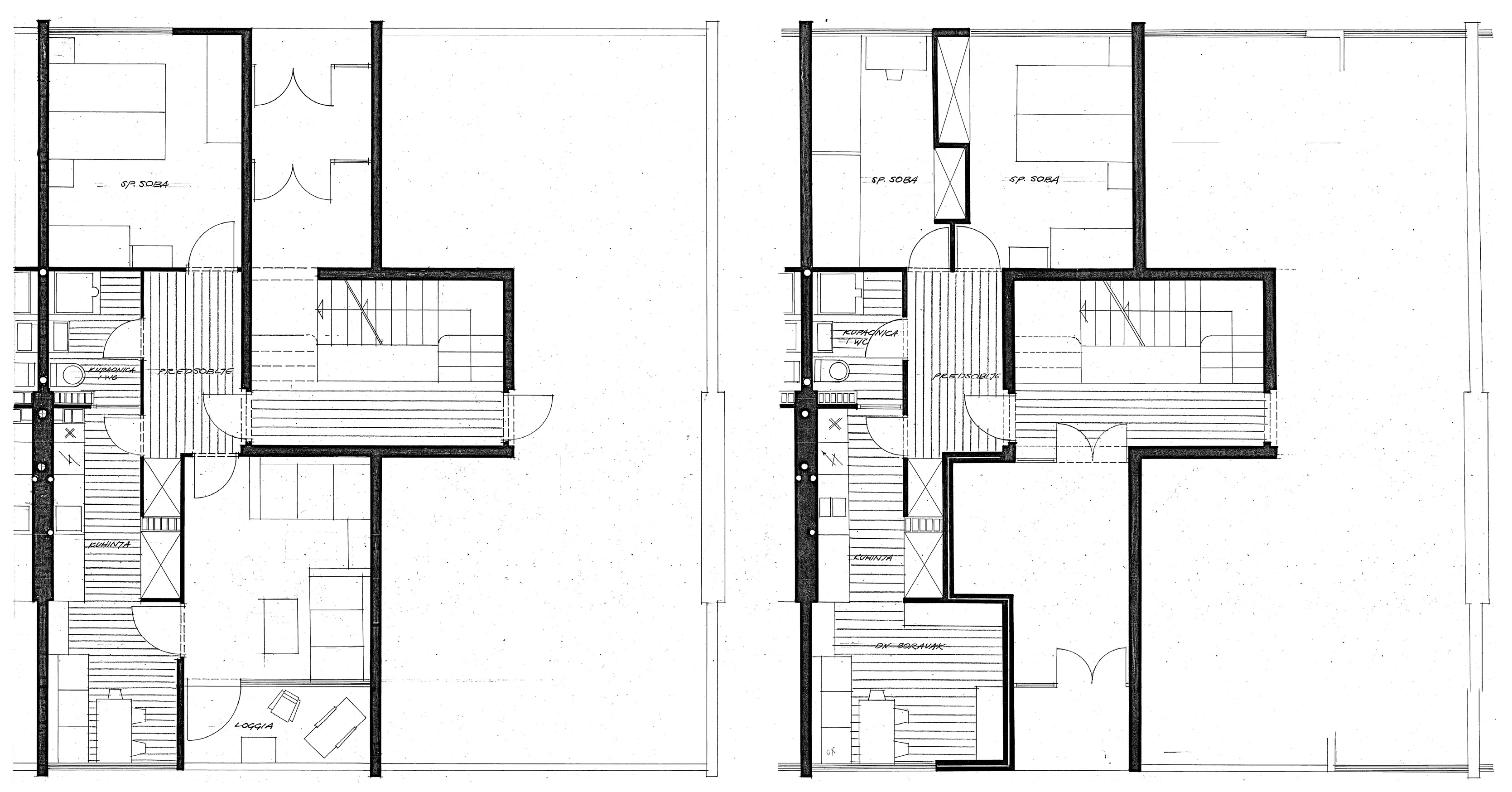

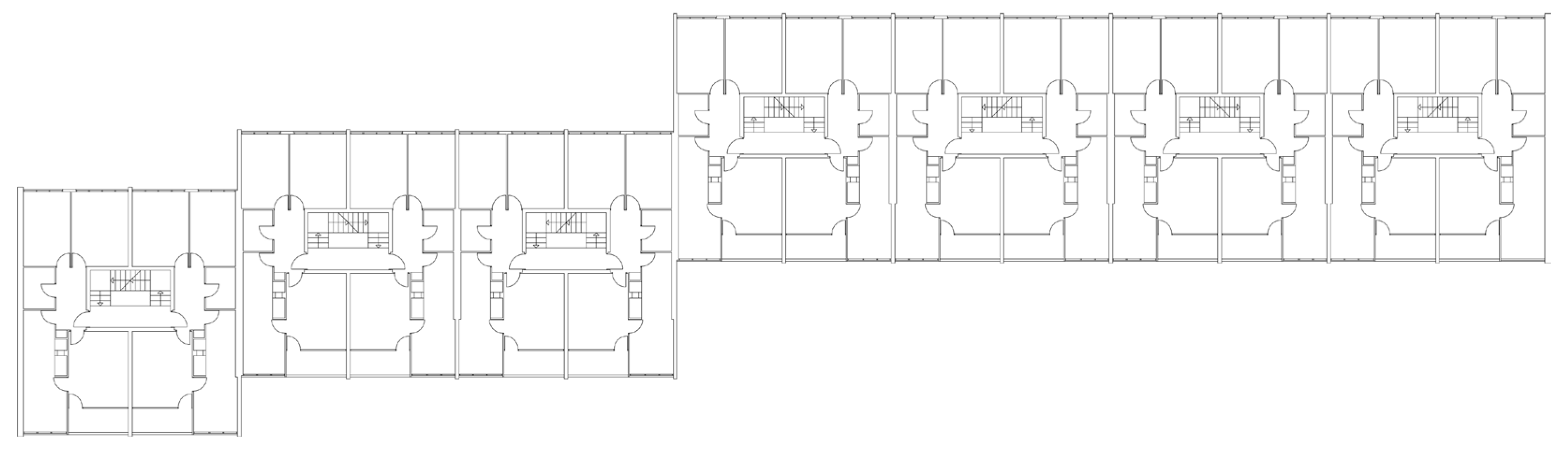

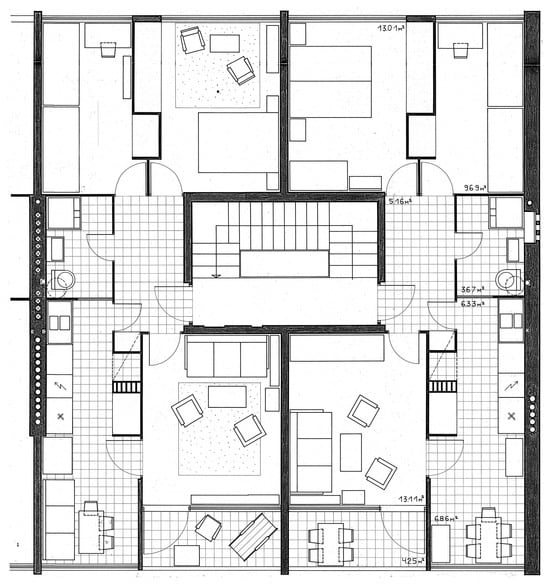

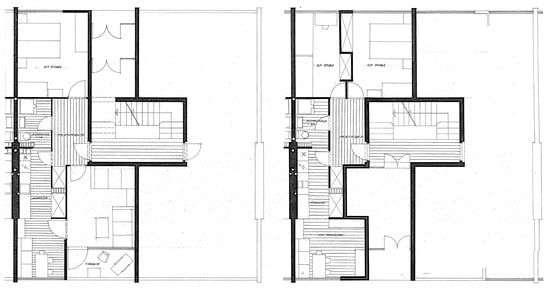

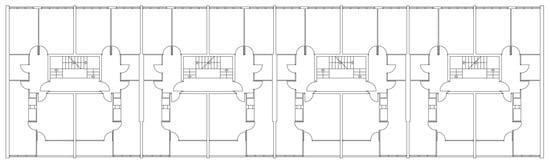

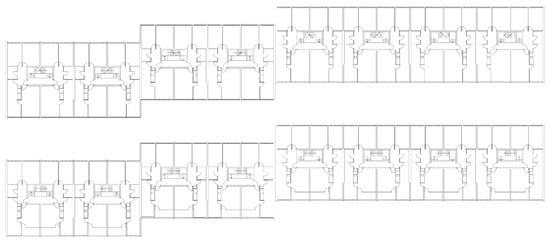

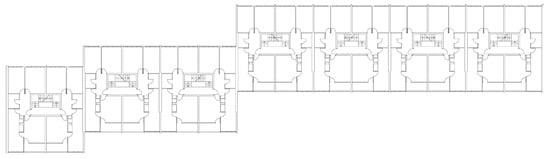

5.2. Typical Building Floor Plans

When designing the URBS 1 standard building, architect Vojnović proposed typical floor plans for all floors. A typical floor unit of the building (a transverse lamella) consists of two standard two-bedroom apartments around a centrally located three-flight staircase that provides access to the apartments. Transverse load-bearing walls with a span of 5.65 m define the space of the residential unit with a relatively large depth and a narrow front façade. This contributes to the cost-effectiveness of the design, but also to more rational use, since less energy is needed to achieve a pleasant climate in the apartment. The longitudinal arrangement of the floor units forms a residential building with a longitudinal or broken floor plan with transverse load-bearing walls. The longer axis of the building is laid in the east–west direction, and the orientation of the apartments is north–south (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A typical floor plan from the 1st to the 4th floor. Source: Ref. [23].

A typical ground-floor level contains the entrance area to the building and two apartments; one is a typical two-bedroom apartment, and the other is a modified typical apartment of smaller size. The entrance to the building is from the south or north side, depending on the location and the position of the access street. In cases where the entrance to the building is from the south, the living room is reduced to a niche within the dining area. When the entrance to the building is from the north, the apartment has one bedroom. The adjacent apartment, which is not reduced in size by the entrance area to the building, is a typical apartment equal to the apartments on the floors in both variants of the ground floor plan (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A typical ground floor with a building entrance from the north (left). A typical ground floor with a building entrance from the south (right). Source: Ref. [23].

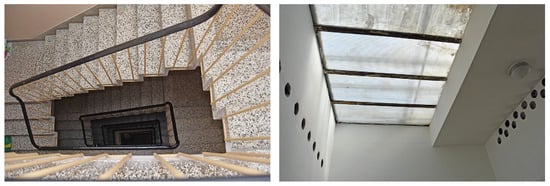

The two apartments on the fifth, top floor are one-bedroom apartments facing south. The remaining part of the fifth floor is a walkable roof terrace facing north, which is used by all residents (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A typical floor plan of the top, 5th floor. Source: Ref. [23].

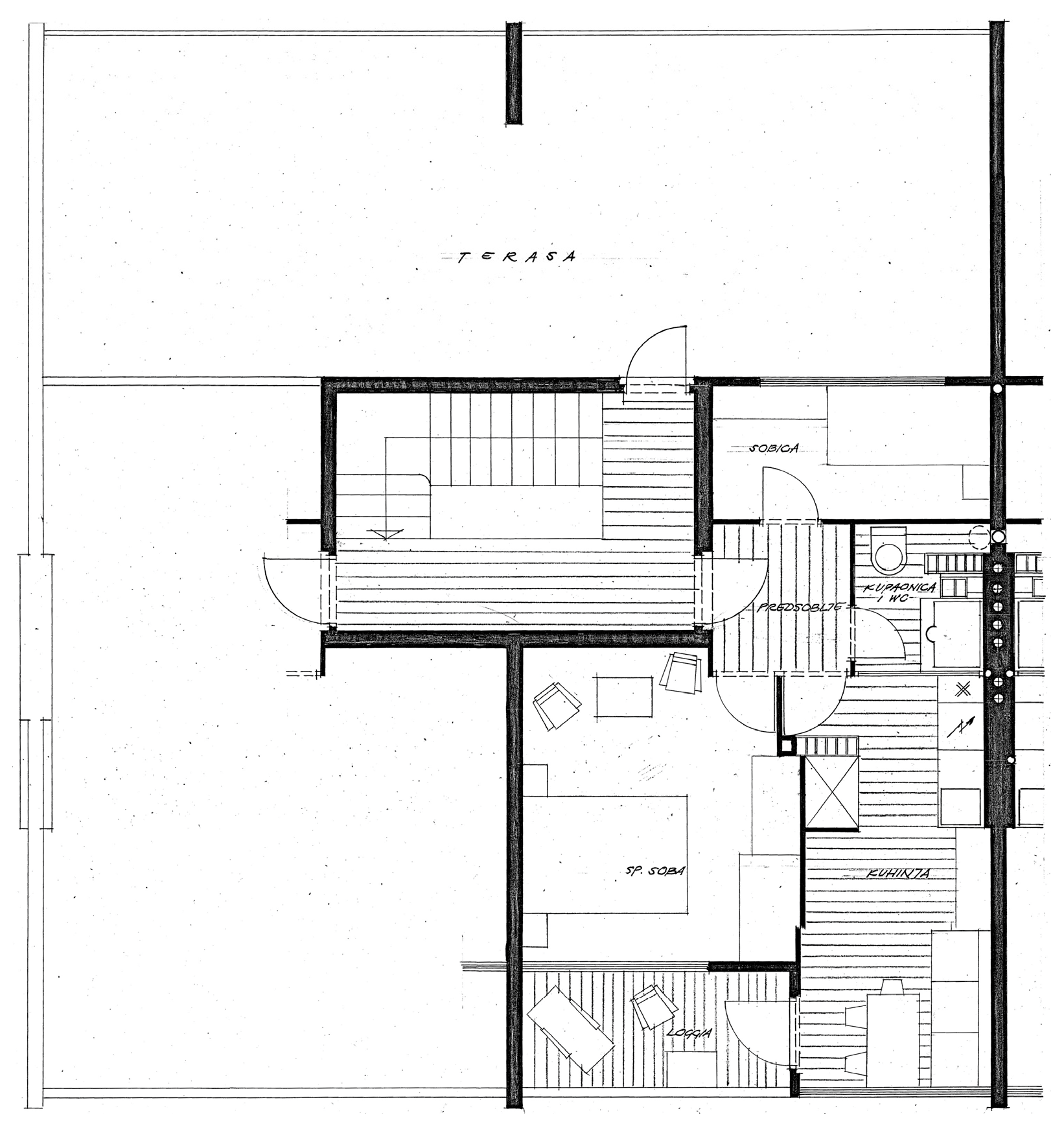

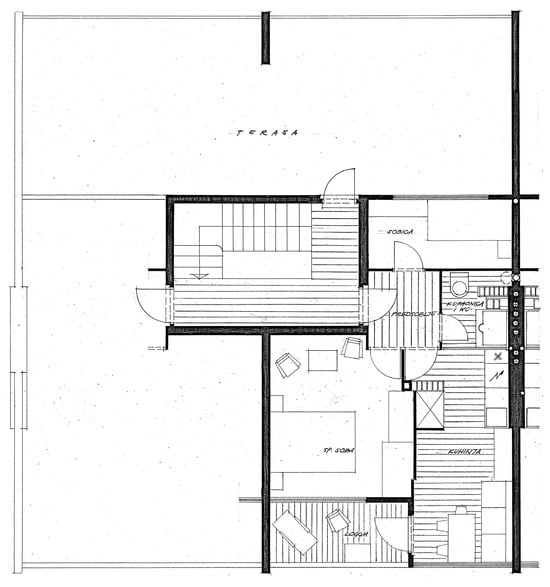

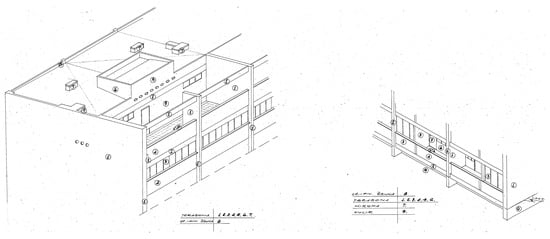

The URBS 1 residential buildings are the first prefabricated buildings in Split [1] (p. 86). The inter-storey structure is semi-prefabricated, type Isteg. This structure was often used in the 1960s and 1970s in Croatia. It consists of prefabricated reinforced-concrete ribs that are 25 cm high and a concrete slab that is 5–10 cm high and made on-site. The transverse reinforced-concrete walls were cast using floor formwork. The façades of the building do not have a load-bearing role and are shaped by loggias, glass walls and ribbon windows with non-load-bearing parapet prefabricated (Monier) walls. The staircase of the building is a three-flight prefabricated staircase. It is of a sawtooth profile, made using the terrazzo technique, and is illuminated from above (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Three-flight prefabricated sawtooth staircase (left). Overhead (zenithal) lighting of staircase (right). Source: author’s archive.

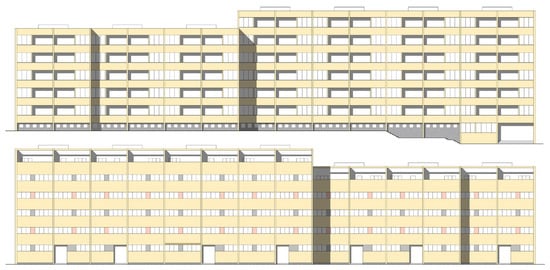

5.3. Typical Building Façades

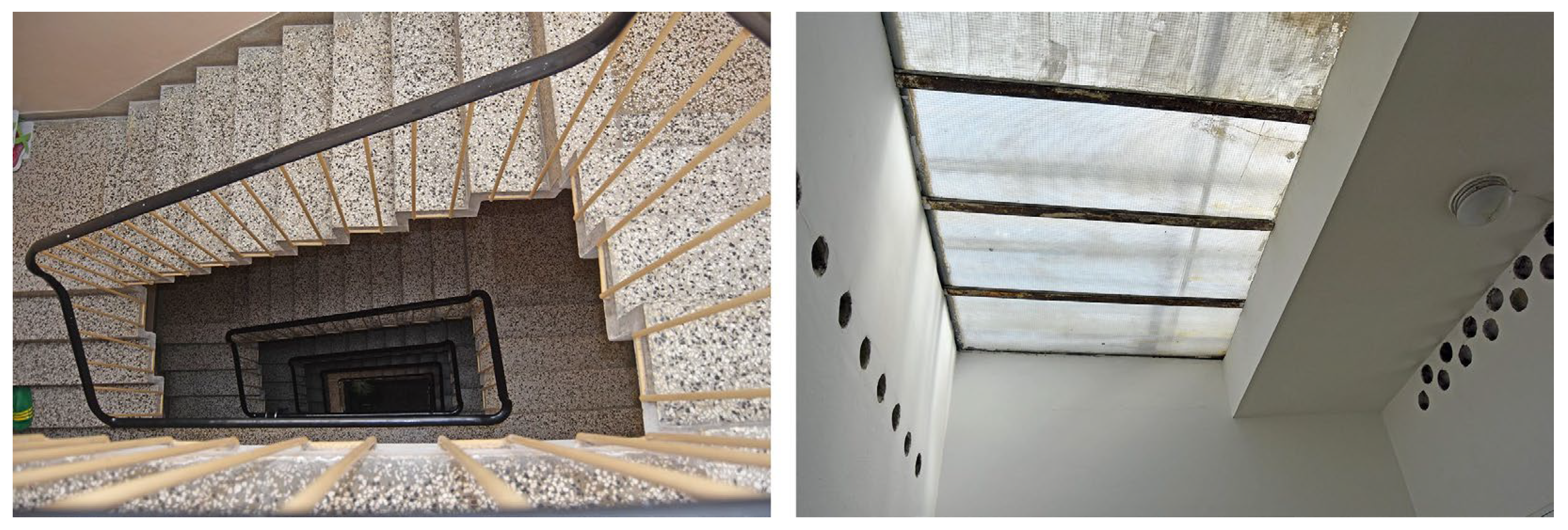

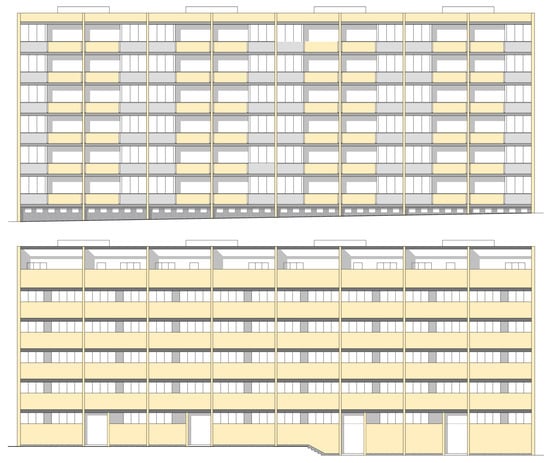

The north and south façades of the building are shaped by the geometric articulation of its planes and by the colour. The surfaces are arranged on different planes along the depth of the façade, with offsets of up to 10 cm. The primary articulation of the façade surface is into rectangular vertical panels, which are defined by vertical lines projecting the load-bearing walls onto the façade plane. These panels are further subdivided by horizontal bands at the floor-slab level and are articulated through loggias, glazed walls and ribbon windows. The façade planes were textured using a fine mineral plaster and either finished with a scraped texture (terabona) or applied using a bush-hammering technique (hirofa). The base of the building, which is 20 to 100 cm high, sometimes even the height of the entire floor, was treated with rusticated (kulier) washed concrete in a predominantly dark-grey tone. (Figure 8 and Figure 9) The façades are painted predominantly in light ochre. Some smaller parts are highlighted in light grey, dark grey, black and red. The railings of the glass walls and loggias, when not full wall parapets, are made of black metal rods. The joinery and sun protection elements, blinds or wooden shutters, are white, or the natural dark brown colour of the wood, while the metal frames of the blinds are black, brown, blue and red. The narrower façades, east and west, are full wall surfaces.

Figure 8.

Surface articulation of the north (left) and south (right) façades. On the north façade (left) terabona (coarse scraped texture) has been marked with numbers 1–7, and gr. i fin. žbuka (coarse and fine plaster) with number 8. On the south façade (right) gr. i fin. žbuka (coarse and fine plaster) has been marked with number 8, terabona (coarse scraped texture) with numbers 1–6, hirofa (sprayed texture) with number 7 and kulir (washed concrete) with number 9. Source: Ref. [23].

Figure 9.

South (left) and north (right) façades of building. Source: author’s archive.

The entrances to the building are recessed into its volume. The building is most often approached via a single-flight staircase, which, depending on the elevations along the building, has a different number of steps. The staircase sometimes descends and sometimes ascends towards the entrance area of the building. A smaller number of buildings are accessed from a pedestrian path along the building (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Different entrance designs in URBS 1 buildings across various locations in Split. Source: author’s archive.

6. Analysis of URBS 1 Buildings Built in Split

The standard residential buildings of the URBS 1 type were constructed at several locations in Split, mostly within the new residential areas built during the 1960s. Each residential settlement within the area, bounded by the city roads and communal infrastructure, was built by a different construction company from Split. The area of the settlement corresponded to the circular reach of a crane, which is why such construction sites are called concentric. The complexes were built first around the perimeter of the historic city centre, and later further eastward on the Split peninsula. The first URBS 1 buildings were erected between 1960 and 1962 in the residential area along Osječka Street (formerly Vrzov Dolac Street and later XX. Dalmatinske divizije Street), and in 1962 in the Skalice city district. In the same year, a building was inserted into the existing urban fabric in Pojišanska Street (formerly Rade Končara Street). In 1964, a URBS 1 building was constructed in the residential settlement in Ljudevita Posavskog Street (formerly Drvarska Street), and in 1967 two additional buildings were built in the city district of Lokve [48] (p. 71). In these buildings, a total of 736 apartments were constructed. (Figure 11 and Figure 12.). In the case of residential buildings along Osječka Street, architect Vojnović applied the original standard floor plan for the apartment, i.e., the building, as well as the standard façade. In the Skalice residential area and the building on Pojišanska Street, the standard floor plans of certain (Skalice) or all floors (Pojišan) of the buildings were slightly modified. This affected the appearance of the façades, causing their design to deviate from the typical façade pattern. Although the floor plans of the buildings in the Lokve residential area are standard, the façades also deviate from the typical pattern. They are simplified and, in terms of structure, texture, and colour, do not follow the typical façade pattern.

Figure 11.

Location of the Republic of Croatia and the city of Split (mark S) in Europe. Source: author’s archive.

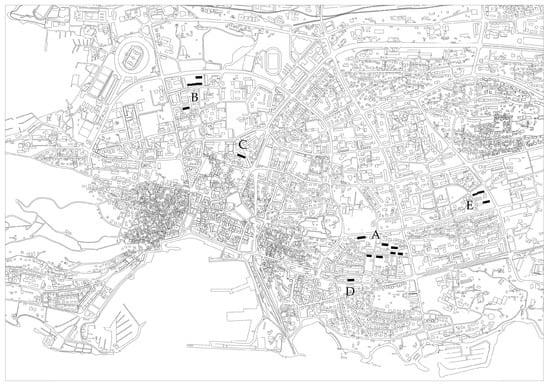

Figure 12.

The locations of URBS 1 buildings by architect Josip Vojnović on the map of the City of Split are marked with capital letters: the buildings in the residential area along Osječka Street—(A); in the Skalice city district—(B); in the residential area along Ljudevita Posavskog Street—(C); along Pojišanska Street—(D); and in the Lokve city district—(E). Source: author’s archive.

6.1. URBS 1 Residential Buildings in Residential Area Along Osječka Street—Project in 1959, Construction from 1960 to 1962

6.1.1. Urban Context

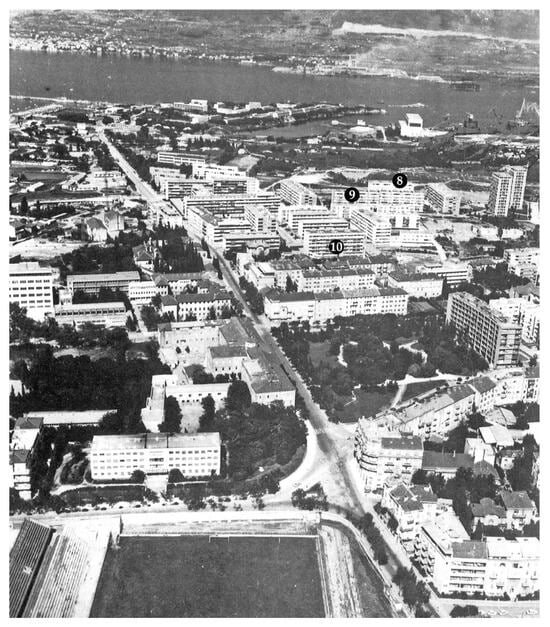

The residential area along Osječka Street (formerly Vrzov Dolac Street, XX. Dalmatinske divizije Street) is located in the central part of the Split peninsula, to the east of the historic core. The settlement was built on the slope of the Gripe hill and faces south. In 1958, architect Petar Mudnić, an employee of the Urban Planning Bureau-Split, drafted the urban planning regulations for the residential area along Osječka Street [49]. Several previously built family houses were retained and incorporated into the urban design of the new settlement, which is predominantly composed of standardised residential buildings designed by architects Josip Vojnović and Lovro Perković. In the construction of the buildings in this settlement, the prefabricated method of building was used for the first time in Split.

Seven URBS 1 standard buildings by architect Josip Vojnović were built in the residential area. These are the buildings at 16, 18, 20 Barakovićeva Street (building no. 1); at 2, 4, 6, 8 Krstulovićeva Street (building no. 2); at 33, 35, 37 Krstulovićeva Street (building no. 3); at 39, 41, 43 Krstulovićeva Street (building no. 4); at 21, 23, 25 Krstulovićeva Street (building no. 5); at 18, 20, 22, 24 Osječka Street (building no. 6); and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 Matice hrvatske Street (building no. 7) (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

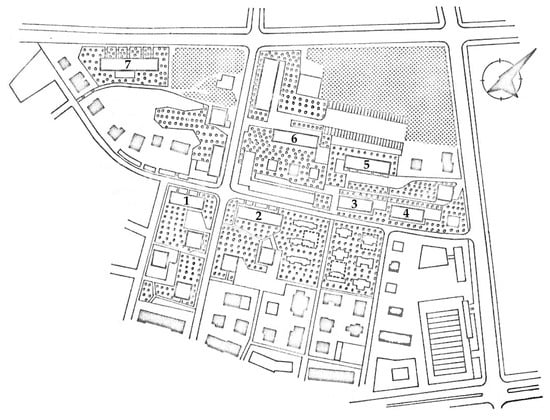

Figure 13.

Layout of the residential area on XX. Dalmatinske divizije Street. The URBS 1 buildings in the residential area along Osječka Street are marked with the numbers 1–7. Source: Ref. [14] (figure no. 17). Marks 1–7 added by the authors of the article.

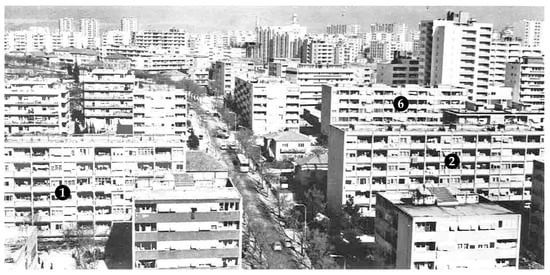

Figure 14.

Residential area along Osječka Street, shortly after it was built. The URBS 1 buildings in the residential area along Osječka Street are marked with the numbers 1, 2 and 6. Source: Ref. [50]. Marks 1, 2 and 6 added by the authors of the article.

6.1.2. Typical URBS 1 Residential Building on Krstulovićeva Street

The residential building at 2, 4, 6, 8 Krstulovićeva Street (building no. 2) has a rectangular floor plan composed of four typical plan lamellae. It is positioned along Krstulovićeva Street and forms its southern façade. The entrances to the building are located on the northern side, so the ground-floor apartments are organised according to the previously explained floor pattern [24,26] (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Floor plan of a typical floor of the building. Source: author’s archive.

The design of the façade follows a standard typological pattern, while the choice of colours of the façades varies somewhat for each individual building within the residential complex. The predominant façade colour of the buildings is light ochre. In the analysed building, the window parapets of the dining rooms on the southern façade and the wall within the band of ribbon windows on the northern, street-facing side are grey. The horizontal bands at the level of the floor slabs on both longer façades, as well as the beam at the top of the upper-most storey on the northern façade, are dark grey. The bedrooms on the northern side of the building are protected from the sun by wooden shutters, which, like the joinery, are painted light grey. On the southern façade, the dining room is protected from the sun by wooden roller shutters in a natural brown colour. The metal frame of the shutters is black, while the joinery is dark brown (Figure 16 and Figure 17).

Figure 16.

South (top) and north (bottom) façades of the building. Source: author’s archive.

Figure 17.

South façade and façade detail, present condition (top). North façade and façade detail, present condition (bottom). Source: author’s archive.

6.2. URBS 1 Residential Buildings in Skalice City District—Project in 1960, Construction in 1962

6.2.1. Urban Context

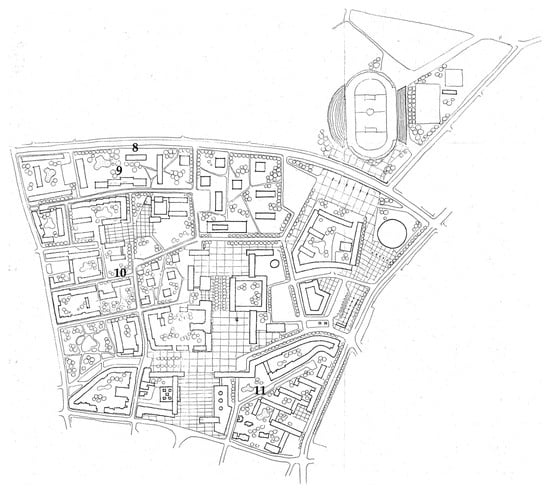

Until the beginning of the 1960s, when its intensive urbanisation began, the area of the city of Split north of the historic core was sparsely built. The construction of this area was aligned with the planned expansion of the city centre, which was planned to expand from the historic city centre within Diocletian’s Palace to undeveloped areas to the north [51,52]. The conceptual design of this project was created in 1959 by architect Berislav Kalogjera, an employee of the Urban Planning Bureau-Split [53,54]. The outer parts were reserved mainly for residential settlements, while the central area was intended for the public urban facilities of the new city center. The Skalice residential district occupies the northwestern section of this area. The buildings are arranged along the new service streets of the residential district and are surrounded by parks. In order to match the heights of the pre-war buildings that were retained in the area, the prevailing building height is five to six storeys above the ground. The residential buildings were constructed in the first half of the 1960s, based on the designs by architects Josip Vojnović, Lovro Perković, Franjo Buškariol and others (Figure 18 and Figure 19).

Figure 18.

Layout of the 4th residential unit. The northeast part is the Skalice city district, and the southwest is the residential settlement in Ljudevita Posavskog Street. The URBS 1 buildings in the Skalice city district and in the residential area along Ljudevita Posavskog Street are marked with numbers 8–11. Source: Ref. [54]. Marks 8–11 added by the authors of the article.

Figure 19.

Skalice city district, shortly after it was built. The URBS 1 buildings in the Skalice city district are marked with numbers 8–10. Source: Ref. [55]. Marks 8–10 added by the authors of the article.

Three URBS 1 standard buildings by architect Josip Vojnović were built in the Skalice residential district. These are the buildings at 23, 25, 27, 29 Put Skalica Street (building no. 8); at 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45 Put Skalica Street (building no. 9); and at 8, 10, 12, 14 Table Street (building no. 10) [27,28,29]. The building footprints and heights were determined by the conceptual urban planning project [54]. Buildings no. 8 and no. 10 have a rectangular floor plan, while building no. 9 is longer, so its floor plan is segmented into three rectangular parts. The buildings are six storeys in height, in accordance with the preliminary urban design (Figure 18 and Figure 19).

The residential building at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 Ljudevita Posavskog Street (building no. 11) was constructed in a smaller residential enclave in the southwestern part of the area. Another planned URBS 1 building in this enclave was never built (Figure 18).

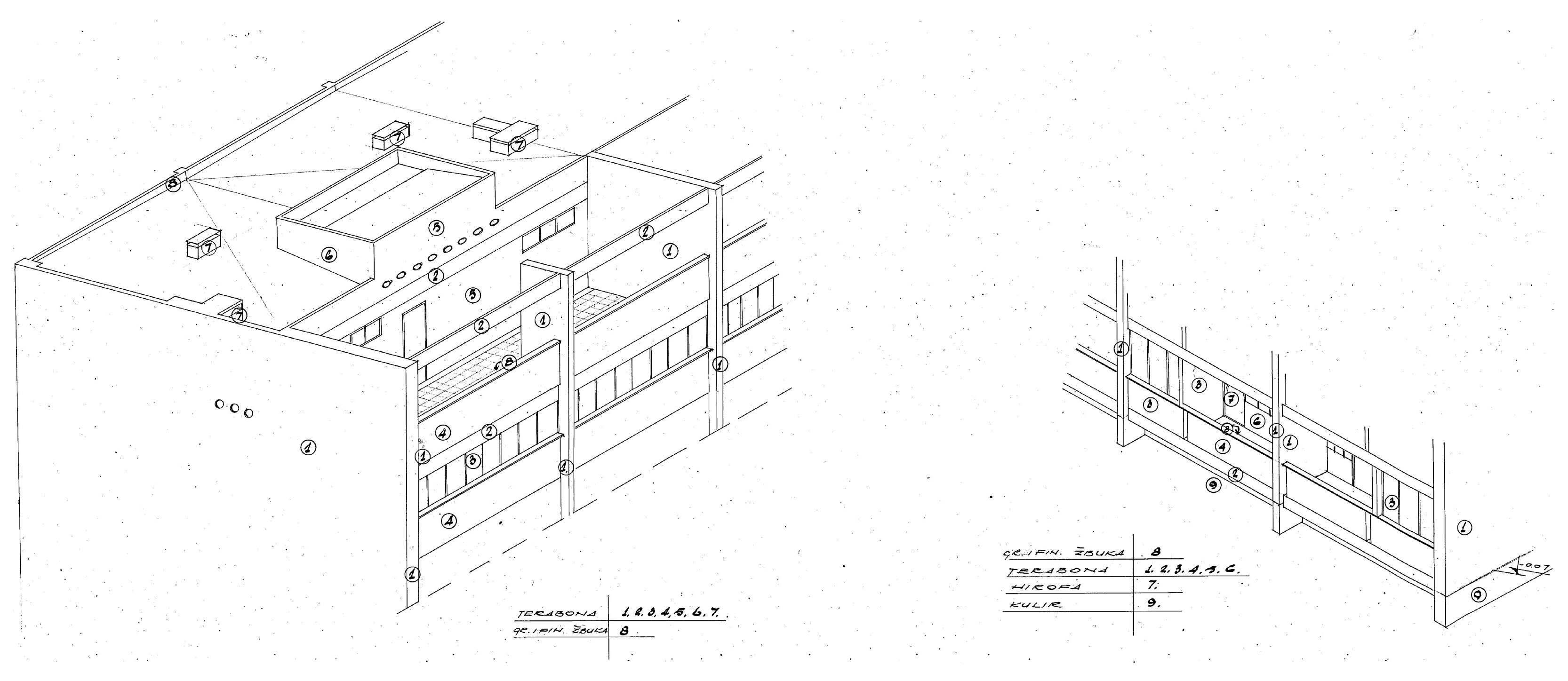

6.2.2. Typical URBS 1 Residential Building on Put Skalica Street

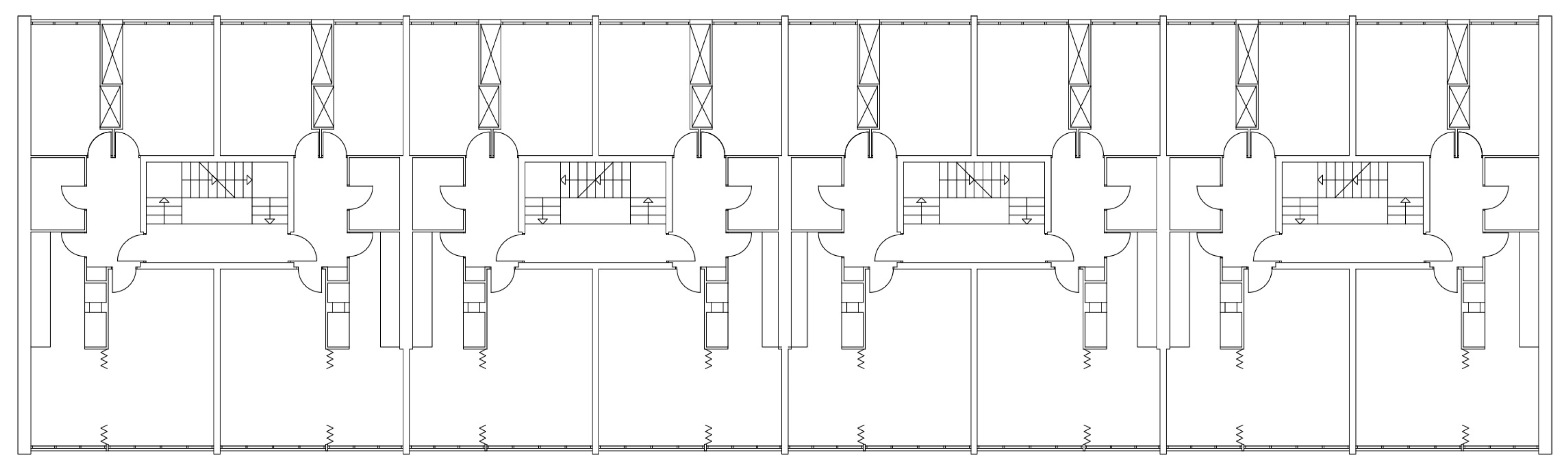

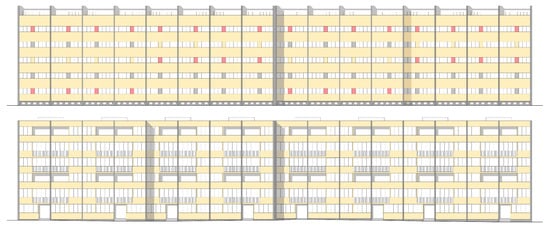

The residential building at 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45 Put Skalica Street (building no. 9) is accessed from the south. Its segmented floor plan is formed by eight typical storey lamellae. In this building, as in the other buildings in the city district of Skalice, architect Josip Vojnović offered two variants of two-bedroom apartments that differ in the size of the living room. In the case of the apartments on the third floor, he retained the typical layout (with the living room with access to the loggia), while on the remaining floors, he proposed apartments with a larger living room featuring a multi-panel glass wall instead of a loggia. (Figure 20) As a result, the southern façade of the building differs somewhat from the typical façade design scheme. Such a typical scheme is maintained on the third and fifth floors, while the façade sections of the first, second and fourth floors are articulated with dining room windows and the glass walls of the living rooms [27].

Figure 20.

Floor plan of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th floors (top). Floor plan of the 2nd floor (bottom). Source: author’s archive.

The predominant colour of the building’s façade is light ochre. The vertical lines of the load-bearing walls highlighted on the façade are black. The walls within the bands of ribbon windows on the northern façade are mostly ochre in colour, with some sections painted red or grey. The joinery is dark blue, as is the metal frame of the wooden shutters, which are in the natural brown colour of wood. The metal railing of the glass wall is black (Figure 21 and Figure 22).

Figure 21.

South façade of building (top). North façade of building (bottom). Source: author’s archive.

Figure 22.

South façade and façade detail, present condition (top). North façade and façade detail, present condition (bottom). Source: author’s archive.

6.3. Residential Building URBS 1 on Pojišanska Street—Project in 1959, Construction in 1961

6.3.1. Urban Context

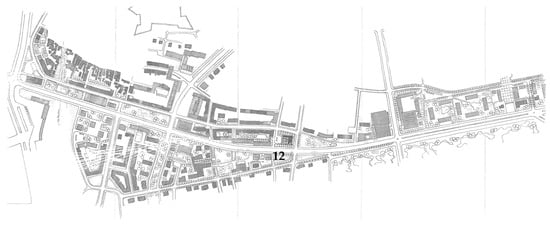

Pojišanska Street (formerly Rade Končara Street) is an access road that from the east leads into the city centre of Split and continues onto Poljička Street. Great attention was devoted to the design of this street, and so in 1960, the regulation plan for the wider Pojišanska Street area was prepared by architect Fabian Barišić of the Urban Planning Bureau-Split. Barišić filled the vacant lots with new buildings in order to complete the block construction that had begun before World War II and to shape the street front that leads towards the historic centre and the City Port [56] (Figure 23).

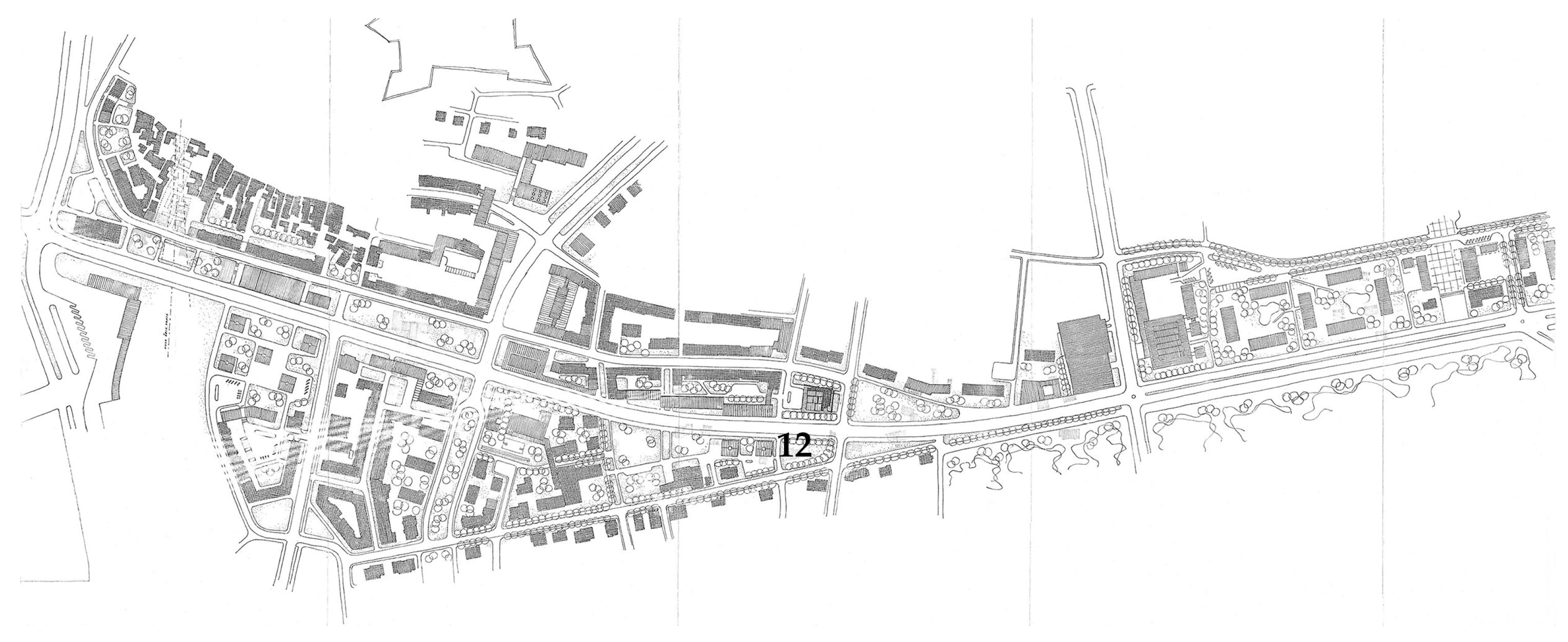

Figure 23.

Conceptual layout of Rade Končara Street. The URBS 1 building along Pojišanska Street is marked with the number 12. Source: Ref. [56]. Mark 12 added by the authors of the article.

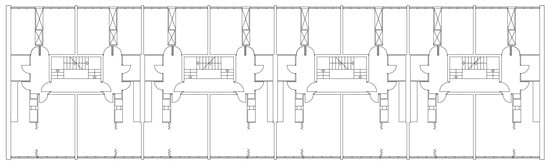

6.3.2. URBS 1 Residential Building on Pojišanska Street

The URBS 1 building at 13, 15, 17, 19 Pojišanska Street (building no. 12) is interpolated into the existing urban fabric. The building is located on the north side of Pojišanska Street and forms its façade. The apartments deviate from the typical floor plan since they do not have loggias (Figure 24). This is reflected in the design of the southern façade, which is articulated by a horizontal sequence of ribbon windows and wall parapets. One window in the sequence is a French window, which is centrally positioned on the upper floors, while on the first floor it is placed at the edge [25] (Figure 25). The longer stretches of the façade of this building are predominantly beige, and the load-bearing walls are highlighted in black. On the southern, street-facing façade, the shutters and joinery are dark brown, while the metal frames of the shutters and the railings of the French windows are black (Figure 26).

Figure 24.

Floor plan of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th floors. Source: author’s archive.

Figure 25.

South façade of the building. Source: author’s archive.

Figure 26.

South façade and façade detail, present condition (top). North façade and façade detail, present condition (bottom). Source: author’s archive. (Revised figure-the order of the two bottom images has been swapped to match the image description and the previous captions.).

6.4. URBS 1 Residential Buildings in the Lokve City District—Project in 1965, Construction in 1967

6.4.1. Urban Context

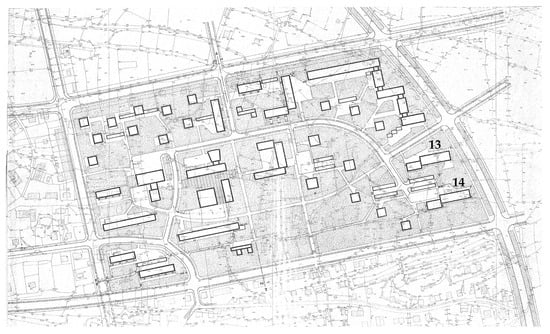

Like the previously analysed housing developments, the Lokve residential settlement, located on the eastern side of Split’s historic core, was part of the city’s periphery in the early 1960s. The urban planning scheme for the settlement was prepared in 1965 by architect Milorad Družeić, an employee of the Urban Planning Bureau-Split [57]. The northern, eastern and western parts of the settlement were intended for housing, while social facilities were planned in the central part, and recreational areas in the south [58]. Buildings with square and rectangular floor plans, surrounded by greenery, are arranged within residential neighbourhoods separated by service streets and pedestrian paths. The height of most of the buildings does not exceed five storeys above the ground. Several 12-storey high-rises were planned within the settlement. A larger number of buildings was constructed in the second half of the 1960s following the designs of architects Franjo Buškariol, Dinko Kovačić, Josip Vojnović, and others.

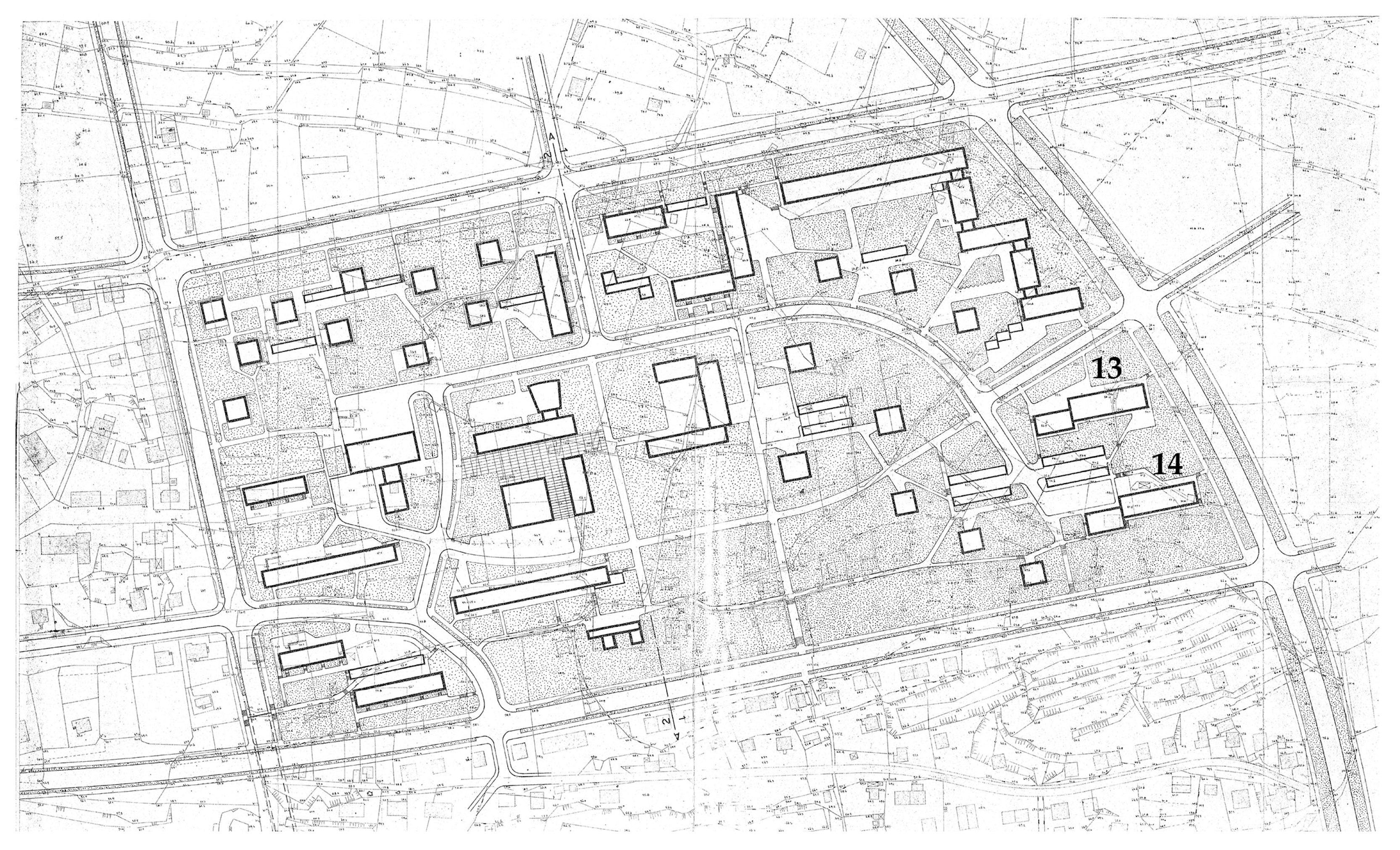

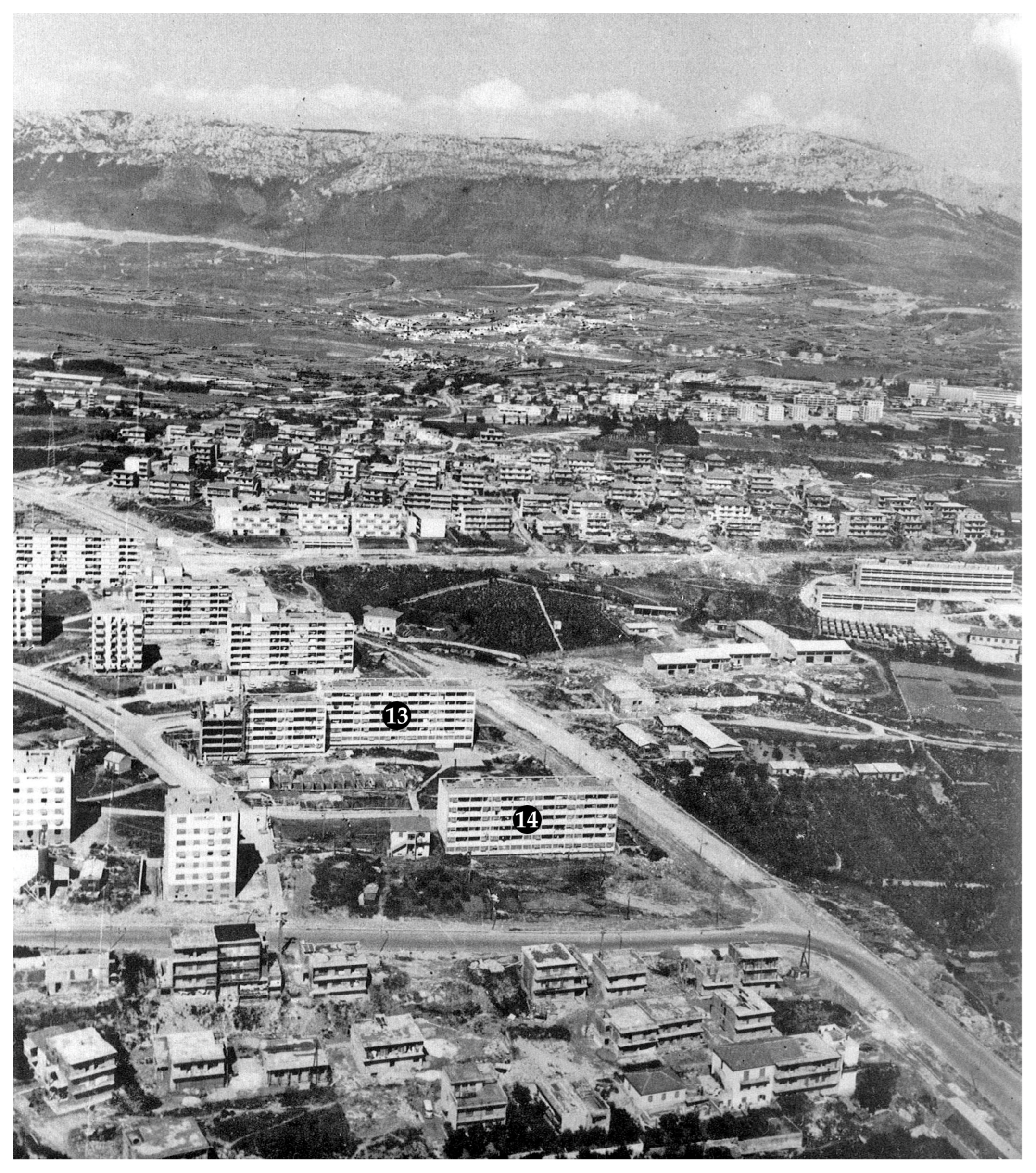

Architect Josip Vojnović prepared designs for four standard URBS 1 buildings in the Lokve city district. Two buildings in the southwestern part of the settlement were never realised [31,32], while two in the southeastern part, at 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34 Jurja Šižgorića Street (building no. 13) [33,34] and at 81, 83, 85, 87 Alojzija Stepinca Street (building no. 14), were constructed in 1967 (Figure 27 and Figure 28).

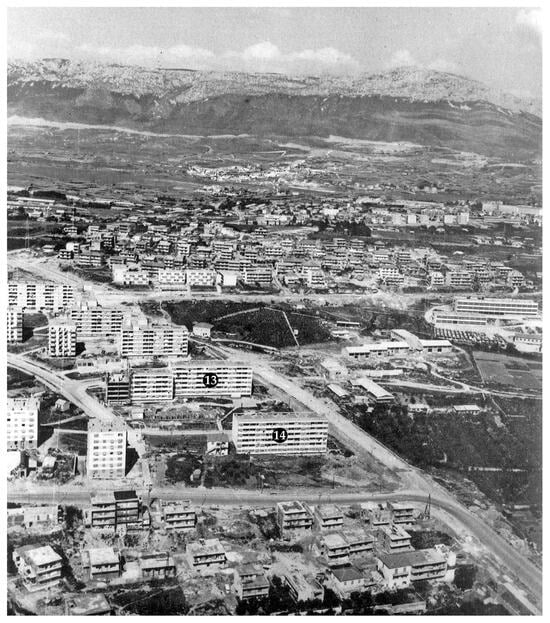

Figure 27.

Urban layout of the Lokve city district. The URBS 1 building in the Lokve city district are marked with the numbers 13 and 14. Source: Ref. [57]. Marks 13 and 14 added by the authors of the article.

Figure 28.

Lokve city district, shortly after it was built. The URBS 1 buildings in the Lokve city district are marked with the numbers 13 and 14. Source: Ref. [59]. Marks 13 and 14 added by the authors of the article.

6.4.2. Typical URBS 1 Residential Building on Jurja Šižgorića Street

The height and segmented floor plan of the building at 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34 Jurja Šižgorića Street (building no. 13) are determined by the urban design of the settlement. The building consists of seven typical storey lamellae and is accessed from the north via the service street of the complex (Figure 29).

Figure 29.

Floor plan of a typical floor of building. Source: author’s archive.

The design of the building’s façade is simplified compared to the typical façade pattern. The longitudinal lines at the level of the floor slabs are omitted, as is the gradation of surfaces in depth [33,34]. The entire south façade is painted in light ochre. The northern façade is also predominantly light ochre, while the wall panels within the horizontal band of windows are light grey on the ground, second, and fourth floors, and pink on the first and third floors. The joinery in the case of this building is white, and the wooden shutters are dark brown with black metal frames (Figure 30 and Figure 31).

Figure 30.

South (top) and north (bottom) façades of the building. Source: author’s archive.

Figure 31.

North façade and façade detail, present condition (top). South façade and façade detail, present condition (bottom). Source: author’s archive.

6.5. URBS 1 Buildings Built in Šibenik, Omiš and Ploče

Apart from Split, URBS-1 buildings have been built in three other Dalmatian cities, namely, Šibenik, Omiš and Ploče. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of the URBS 1 residential building in Split, Šibenik, Omiš, and Ploče.

In Šibenik, four buildings were built in the Baldekin city district (12, 14, 16, 18 Petra Preradovića Street; 78, 80, 82, 84 Stjepana Radića Street; 90, 92, 94, 96 Stjepana Radića Street; and 115, 117, 119, 121, 123, 125, 127, 129 Stjepana Radića Street), four buildings in the Šubićevac city district (8, 10, 12, 14 Bana Josipa Jelačića Street; 16, 18, 20, 22 Bana Josipa Jelačića Street; 38, 40, 42, 44 Bana Josipa Jelačića Street; and 46, 48, 50, 52 Bana Josipa Jelačića Street) and one in the Crnica city district (2, 4, 6 Stipe Ninića Street). Along the southern, shorter façades of the two URBS 1 buildings on Stjepana Radića Street, two architecturally inappropriate residential buildings were subsequently added, which, with their reduced postmodernist design, do not follow the architectural features of typical URBS 1 residential buildings.

A building was also built in Omiš (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 Joke Kneževića Street), but its volume and design were not adapted to the perimeter of the historic core. Although the typical URBS 1 building was primarily intended for the construction of new residential settlements, this building is the only one built close to the historic part of a town [60].

Two more buildings were built in Ploče (8, 10, 12 Vladimira Nazora Street and 16, 18, 20 Vladimira Nazora Street).

7. Conclusions

The URBS 1 standard residential buildings were designed and built as one of a series of standardised models for solving the housing shortage in Split and Dalmatia in the 1960s. A total of 14 such buildings were built in Split at four locations: seven buildings in the residential area along Osječka Street, three buildings in the city district of Skalice, two buildings in the district of Lokve, one building in Ljudevita Posavskog Street and one on the northern side of Pojišanska Street in the already mostly built-up part of the city. The URBS 1 standard residential buildings were also built in three other Dalmatian cities. In Šibenik, buildings were built in two city districts, namely three buildings in Baldekin and four buildings in Šubićevac. One URBS 1 building was built in Omiš and two in Ploče.

The typical floor plans of the URBS 1 buildings differ in the number of repeated typical floor units and in the design of the elongated or segmented rectangular building plan. The elongated rectangular floor plan was applied several times, while the segmented rectangular one was used only twice in the city districts of Skalice and Lokve.

The URBS-1 standard buildings were accepted as an appropriate example of standardised buildings that successfully solved the problem of housing shortages during the 1960s in Split and Dalmatia.

The repeated implementation of these buildings by Josip Vojnović and other typical residential buildings by other authors was initially approved by the professional community, the municipal government and the interested public—at the time, mainly due to their economy and speed of construction.

Apart from approval, criticism also emerged over time. This, according to some experts, was due to the excessive multiplication of identical and series of uniform buildings, and of the same pattern of apartments. Historian Duško Kečkemet also highlighted the insensitivity to the specific conditions of the locations and to the general ambience, as well as to the architectural tradition. He described these, and other similar residential buildings of standardised architectural design, as uniform and monotonous [61]. Also, in addition to the problem of the excessive reduction in the floor area of the apartment and the clear ceiling height of the rooms, architect Frano Gotovac pointed out the use of cheap construction materials when building the apartments [62].

The technical and artistic values and achievements of the URBS 1 standard buildings were observed and re-evaluated in relation to a complex network of circumstances that conditioned and determined their emergence.

Analyses have determined that the URBS 1 residential buildings are functionally well-designed. This is reflected in the balanced ratio between the areas of the buildings’ common spaces and the apartments, as well as in the size, layout, number of rooms, and equipment of the apartments. In terms of area and equipment, entrances and staircases were designed to achieve a functional optimum. Everything within the apartments is dimensioned and arranged functionally, as well. Apartment modifications have been neither frequent nor simple due to the prefabricated modules, which limit the possibilities for alterations. In addition, the analyses have also shown that the URBS 1 standard buildings are adequately adapted to the specific conditions of each location and the environment. The locations of the access streets determined the choice of a typical ground-floor plan of the buildings with south- or north-oriented entrances. The buildings were adapted to different terrain configurations and elevations along them. They are accessed via a pedestrian path or a staircase, which the architect Vojnović designed and adapted in different ways.

The façade design of the buildings was carefully conceived through the structuring of surfaces and the choice of textures and colours. The typical façade pattern was modified by architect Vojnović after the construction of the first buildings in the residential settlement along Osječka Street. Therefore, the façades of the buildings erected in the Skalice and Lokve city districts and the façades of the interpolation along Pojišanska Street differ somewhat from the original typical façade. By choosing different colours, different patterns were created on the façades of buildings, even within the same residential area. Through this approach to exterior design of the buildings, architect Vojnović contributed to the recognition of individual residential buildings and to the overall ambience (and sense of cohesion) of the residential complex rather than the monotony and uniformity with which these residential complexes built in the 1960s in Split have been described (without deeper analysis). Residential areas from this period have gradually been adapted to contemporary urban and architectural housing standards and lifestyle culture, and often do not fall short of the standards of comparable modern housing. Compared to certain modern developments with similar residential buildings, the housing standards in these residential areas are even better in some cases. In the former, the apartments are reduced to minimal floor areas and maximum numbers of rooms, and the layout of building plots and neighbourhoods is limited to meeting the minimal urban parameters prescribed by urban plans.

Compared to the problems some mass housing estates from the second half of the 20th century face at the beginning of the 21st century, URBS 1 standard buildings have successfully maintained their use and value. Once built in the suburbs of Split, they are now located in the wider central area of Split. Since the city is developing as a tourist destination, the demand for apartments is very high, and the value of the existing ones is not decreasing. Carefully designed greenery is well-maintained and adds value to the estates. Although these apartments were originally designed to meet the needs of middle-class or affluent working-class families in the 1960s, they are still successfully meeting the needs of the contemporary Croatian household. This is due to its downgrading from an average of 3.8 members in 1953 to an average of 2.7 members in 2021 [63].

Today, the buildings are in good structural condition, but their façades have mostly been degraded by recent unprofessional renovations. They have been painted inexpertly and with inappropriate colour choices. On some buildings, a uniform layer of plaster has negated the original geometric dynamism, as well as the façade’s structure and texture. Compared to the author’s original idea, the artistic quality of the architectural design of the building was thus impoverished and deprived of the geometricity that was emphasised by texture and colour. Wooden roller blinds and shutters have been replaced mostly with plastic ones, most often in white or brown, depending on the wishes of the tenants.

The URBS-1 standard residential buildings are a high-quality and illustrative example of Split and Dalmatian residential construction in the 1960s due to their number, wide distribution and, above all, architectural features determined by the economic, social and cultural context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; methodology, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; software, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; validation, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; formal analysis, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; investigation, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; resources, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; data curation, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; visualisation, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; supervision, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; project administration, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M.; funding acquisition, V.P., N.M.K. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, project KK.01.1.1.02.0027, which is co-financed by Croatian Government and the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund-the Competitiveness and Cohesion Operational Programme, the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Architecture, institutional project “Adaptability of Buildings” and the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Architecture, institutional project “Urban and architectural characteristics of a modern and contemporary city”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tušek, D. Architectural Competitions in Split 1945–1995; Split Society of Architects, Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Split: Split, Croatia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gamulin, M. Residential Architecture in Split from 1945 Until Today; Arhitektura, 1–3 (208–210); Savez Društava Arhitekata Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 1989–1991; pp. 28–32. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=11200&tify={%22pages%22:[30],%22view%22:%22info%22} (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Muljačić, S. Construction of Split 1944–1969; URBS 8; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1969; pp. 7–42.

- Muljačić, S. Construction of Split 1944–1990. In Split in Tito’s Era/Memento on the 110th Anniversary of the Birth, 22nd Anniversary of the Death of Josip Broz Tito and the 58th Anniversary of the Liberation of Split; Čurin, M., Ed.; Society “Josip Broz Tito”—Split/The Association of Anti-Fascist Fighters and Anti-Fascists—Split: Split, Croatia, 2002; pp. 200–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tušek, D. (Ed.) Split 20th Century Architecture. A Guidebook; Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, University of Split: Split, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tušek, D. A Lexicon of Split Modern Architecture; Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, University of Split: Split, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rošin, J. Josip Vojnović and Split 3. In The Arthitects Unplugged; Alfa: Zagreb, Croatia, 2023; pp. 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Perković, L. Review of the Architectural Achievements of the Urban Planning Bureau; URBS 7; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1967; pp. 29–46.

- Works of the Urban Planning Bureau 1947–1967: Architectural Projects; URBS 7; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1967; pp. 74–80.

- Arheološka, Arhitektonska I Likovna Baština. In Split. Hrvatska Enciklopedija, Mrežno Izdanje. Leksikografski Zavod Miroslav Krleža. 2013–2025. Available online: https://www.enciklopedija.hr/clanak/split (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Vojnović, J. Chronological List of Professional, Scientific and Educational Work: Period from 1954 to the Present; Archives of Faculty of Civil Engeenering, Architecture and Geodesy in Split: Split, Croatia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tušek, D. Josip Vojnović, 1929–2008. In Čovjek I Prostor, 1–2; Croatian Architects’ Association: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008; p. 75. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=11287&tify={%22pages%22:[77],%22panX%22:0.733,%22panY%22:0.681,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.589} (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- In Memoriam: Architect Josip Vojnović. Available online: https://dugirat.com/kultura/68-urbanizam/5895-in-memoriam-arhitekt-josip-vojnovi-v15-5895 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Vojnović, J. Rationalisation and Evolution of Housing and Communal Construction in the Processes of Planning, Organisation and Programming. Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Architecture, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, M. Mass Housing: Modern Architecture and State Power—A Global History, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, D.B.; Tammaru, T.; van Ham, M. (Eds.) Lessons Learned from a Pan-European Study of Large Housing Estates: Origin, Trajectories of Change and Future Prospects Housing. In Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclús, J.; Díez Medina, C. Modernist housing estates in European cities of the Western and Eastern Blocs. Plan. Perspect. 2016, 31, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, E. CIAM and Its Outcomes. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 3rd ed.; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vezilić Strmo, N.; Delić, A.; Kincl, B. Causes of Problems in the Existing Housing Stock in Croatia. Prostor 2013, 21, 340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Mrčela, V. Selected Aspects of Supply and Demand in Yugoslav Housing Construction from 1945 to the Present. Covjek. Prost. 1981, 344, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, K.; Van Kempen, R. Large Housing Estates in Europe: Current Situation and Developments. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2004, 95, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 188/id Typical Residential Building; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1958.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 188/po Typical Residential Building; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1958.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 265/po Typical d Residential Building URBS 1A, Rade Končara Street, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1959.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 271-V7/po Typical Residential Building URBS-1, V7, Vrzov Dolac Street, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1959.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 299/gl Typical Residential Building URBS 1A, “S-4”, Skalice, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1960.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 299/gl Typical Residential Building URBS 1A, “S-5”, Skalice, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1960.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 299/gl Typical Residential Building URBS 1A, “S-6”, Skalice, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1960.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 446/gl Typical Residential Building URBS-1, Split, Lj. Posavskog Street; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1963.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 615/1-gl Residential Building URBS-1, No. 37, Gripe-Lokve, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1965.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 615/2-gl Residential Building URBS-1, No. 37, Gripe-Lokve, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1965.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 616/1-gl Residential Building URBS-1, Lokve, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1965.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., 616/2-gl Residential Building URBS-1, Lokve, Split; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1965.

- Čičin-Šain, Č.; Pervan, B.; Vekarić, Z. The Directive Regulatory Basis of the City of Split; Arhitektura 5–8; Savjet Društava Arhitekata Jugoslavije: Zagreb, Croatia, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- The Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia-Split. Master Urban Plan of Split; Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia: Split, Croatia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Perković, L. For a More Rational and Social Conception of Architecture; URBS 1, Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1957; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Muljačić, S. Chronological Overview of the Construction of Split in the 19th and 20th Centuries (1806–1958). In Proceedings of the Union of Associations of Engineers and Technicians in Split; Zajednica Udruga Inženjera i Tehničara u Splitu: Split, Croatia, 1958; pp. 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Marasović, T. Development of the Residential House in Split: From the Early Middle Ages to the Present Day. In Proceedings of the Union of Associations of Engineers and Technicians Split; Zajednica Udruga Inženjera i Tehničara u Splitu: Split, Croatia, 1958; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sumić, D.; Perković, L. Housing Situation in Split/Current State, Opportunities and Paths to Resolution. In Proceedings of the Union of Associations of Engineers and Technicians in Split; Zajednica Udruga Inženjera i Tehničara u Splitu: Split, Croatia, 1958; pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pervan, B. Organisation of Residential Construction in Split; URBS 1; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1957; pp. 47–50.

- To Determine the Final Residential Development Plan. In Slobodna Dalmacija (12.3.1956); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1956; p. 4.

- Cost-Effective Designs. In Slobodna Dalmacija (29.3.1956); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1956; p. 6.

- To Prioritise the Construction of Apartment Blocks. In Slobodna Dalmacija (4.4.1956); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1956; p. 4.

- How to Address the Housing Issue. In Slobodna Dalmacija (1.-3.5.1956); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1956; p. 12.

- To Draw on the Experience of Other Cities. In Slobodna Dalmacija (28.1.1957); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1957; p. 4.

- More on Low-Cost Housing Construction. In Slobodna Dalmacija (9.11.1957); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1957; p. 2.

- Chronological Review of the Construction of Split 1944–1969; URBS 8; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1969; pp. 47–101.

- Mudnić, P. VII-VIII Residential Unit; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966; pp. 109–110.

- Ivan Lučić Lavčević, Split. Jugoslavia: 1948–1978; I. L. Lavčević: Split, Croatia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogjera, B. Split—Study on Urban Regulation of the City Centre; URBS 3; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1959; pp. 9–32.

- Kalogjera, B. The New Town Centre; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966; pp. 71–73.

- Kalogjera, B. “Skalice—Glavičine” Residential Unit; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966; pp. 86–88.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., IV-D/2 Urban Regulation of the Skalice District, Preliminary Design; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1959.

- Graphic Attachment No. 9—Skalice Tabla; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., D-XXXIX Rade Končara Street, Preliminary Urban Plan; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1960.

- National Archives in Split. HR-DAST-119 Urban Planning Institute of Dalmatia—Split, Sign. 2.7., SP-XIII/5 Urban Design Project for the Gripe-Lokve Residential District; National Archives in Split: Split, Croatia, 1965.

- Družeić, M. “Gripe—Lokve” Residential Unit; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966; pp. 103–105.

- Graphic Attachment No. 8—Lokve; URBS 6; Urban Planning Bureau-Split: Split, Croatia, 1966.

- Barišić Marenić, Z.; Perković Jović, V. Modernism in the Mediterranean: Omiš, Croatia, Urban and Architectural Development of the Dalmatian City in the Second Half of the 20th Century. Heritage 2023, 6, 3921–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kečkemet, D. City for Man; Book XXVII; The Croatian Society of Art Historians: Split, Croatia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gotovac, F. Humanisation of Space. Slobodna Dalmacija, (1.-3.1.1963); Nakladni Zavod Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1963; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Croatia; Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Decline in the Number of Households with Three or More Members, and Increase in Single-and Two-Person Households. Published on 31 May 2023. Available online: https://dzs.gov.hr/vijesti/pad-broja-kucanstava-od-tri-i-vise-clanova-a-porast-broja-samackih-i-dvoclanih-kucanstava/1565 (accessed on 20 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.