Abstract

Traditional housing is a type of housing that emerged during a specific era in history, when inhabitants designed and built their own houses with the help of the entire community. In Togo, a West African country, and specifically in the urban area of Kara, traditional housing is characterized by a variety of styles due to socio-temporal changes. This study aims to analyze the dynamics of traditional housing in this urban area following these changes. The results were obtained using a methodological approach based on documentary research, interviews, field observations, GPS surveys and sketches of existing traditional buildings in the urban agglomeration of Kara. Qualitative and quantitative data were also collected. According to the methodology adopted, a total of 327 households out of a total of 24,512 were surveyed and 34 interviews were conducted. This approach reveals that the urban agglomeration of Kara has three (03) types of traditional housing depending on changes and evolution within the community. The first type, known as the original type, is characterized by round-shaped houses covered with straw and built using purely traditional methods. The second type is marked by a change in the original forms. In addition to the original round shapes, rectangular or square shapes are added, using traditional materials and techniques, with the beginning of the use of imported materials. The third type is characterized by the use of modern materials, creating a mix of shapes and materials.

1. Introduction

In their quest to protect themselves from external dangers, to create privacy and comfort, but also to develop their activities, humans have, over the course of history, built a wide variety of habitats, from the simplest shelter to the most elaborate urban complexes, as well as traditional dwellings using locally available materials [,,].

Traditional housing is a type of dwelling housing of a specific period, in a country, of a territory, geographical or cultural zone [], in which the inhabitants designed and built their own homes [], with the help and assistance of their peers and the whole community. It is also a collection of buildings, whatever their shape or size, built mainly of earth and bearing witness to the know-how and techniques of the ancestors []. This type of habitat, found all over the world, is characterized by perfect, harmonious integration with the site, and the use of traditional techniques and local materials to ensure comfort while respecting the environment []. Today, traditional housing is recognized as a testimony to the past, a heritage to be preserved and passed on []. It is characterized by buildings made with local materials [], such as earth, stone, straw, wood, etc. [], with traditional building techniques based on the know-how and indigenous knowledge of peoples and ethnic groups, populations which have for centuries been able to adapt materials to specific ecological, economic and socio-cultural conditions [].

Classified as one of the most representative forms of traditional housing, earthen architecture is seen as a symbolic expression of the human ability to create a built environment by making the most of locally available resources [,]. Characterized by low-cost, easy-to-use buildings, this is sustainable architecture, with the possibility of reusing materials at the end of their life cycle in the construction of new buildings []. The protection and enhancement of earthen architectural heritage is increasingly at the heart of sustainable development issues, as awareness grows of the need to adopt more environmentally friendly lifestyles. Ecological construction, including raw earth housing, is booming, as the building and construction industry is one of the sectors most concerned by the challenges of sustainable development []. From [], raw earth has very interesting thermo-hygro-mechanical properties, which can help to reduce the environmental impact of buildings not only during construction but also during their lifetime.

Traditional architecture is a testimony to the diversity of cultures and lifestyles, passed down from generation to generation and specific to a given community or country []. In Africa, it is characterized by local materials such as earth, stone, wood and straw, and is essentially shaped by a number of environmental, ecological, sociological, demographic, geographic, religious and climate-related factors []. It is also shaped by natural conditions, notably the climate, vegetation and soil [], and by the absence of construction specialists, each one working for himself according to virtually unchanging techniques handed down from generation to generation []. Each actor plays a specific role in the construction process. From [], the man plays the essential part, the woman plasters and decorates, and the young people are responsible for transport, especially water by the young girls. Indeed, ancient African societies are known for the exceptional character of certain significant elements of their architectural and landscape heritage. Within this African architectural heritage, stone and earthen constructions play an important role. Earthen architecture is represented by monumental buildings and constructions of quality that have stood the test of time. The earthen mosques of Mali (Djenné, Tombouctou, and Gao) and the Toloy granaries (2nd–3rd century) have nothing to envy of medieval European cathedrals or some emblematic Asian constructions of the same period such as Machu Picchu and the Taj Mahal []. The high representation of earthen buildings on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List, estimated at around 17% of archaeological and architectural historic sites, representing 120 listed ensembles, although hundreds more deserve to be listed [], testifies to the authenticity and originality of the ancestral skills of earthen architecture.

Despite its modest size, Togo is no stranger to traditional architectural treasures []. From [], in Lomé, there is a whole range of architectural creations by and for the inhabitants themselves, which makes the city unique and the old districts astonishingly rich. Togo’s population is characterized by a mosaic of ethnic groups of all sizes and origins, whose traditional architecture derives from daily customs, forms of belief, economic conditions and the degree of cultural development of the surrounding environment. Adapted to the family structure, it evolves according to the family’s needs. Examples include the royal palaces of Aného in the maritime region, the caves of Nano in the Savanes region, and the Tata of the Tamberma of the Batammariba ethnic group in the Kara region, whose ingenuity in design, organization and construction of their dwellings was recognized by the inclusion of the Koutamakou site on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 2004, illustrating this traditional architecture marked by the ingenuity of the people in the design and construction of their buildings. As stated in [], each geographical area within a country has its own vernacular architecture, shaping unique landscapes.

In the urban agglomeration of Kara, traditional housing is characterized by the courtyard element. The various elements making up the architectural ensemble are arranged around it []. Unlike traditional Herati houses, which are characterized by a series of rooms arranged around a rectangular courtyard [], the courtyard of traditional houses in the urban agglomeration of Kara is circular. The courtyard is a distinctive feature of many traditional Black African houses []. Puddled earth or rammed earth remains the main building material for traditional dwellings in and around the urban agglomeration of Kara. Coatings are made from earth mixed with cow dung, locust bean tree pods, shea butter, straw, etc. [,], and decorations are made with animal remains and horns. Work is carried out in communities, marked by a strong bond of socialization to the rhythm of beautiful and melodious songs that convey the history of the elders and at the same time give advice to the youngest members of society. The courtyard is treated with shards of broken pottery, while the rooms are tamped with earth by the women []. These construction techniques and materials protect the yard from erosion and provide a particularly effective system for protecting and beautifying the soil. The foundations of the houses are reinforced with local stone to protect the houses. Drawing on its cultural and architectural potential, as well as socio-temporal changes and the evolution of building materials, the urban agglomeration of Kara records a series of traditional building styles that trace the history and ingenuity of mankind from the choice of site, through spatial organization, to the final erection of the edifice. Their way of life, their way of thinking, their social organization and their traditions are also represented through their habitats [].

Despite all this potential, traditional housing around the world is increasingly undergoing radical change, due to the evolution of lifestyles and societies, colonization and the emergence of new needs [], rapid urbanization [], strong population growth [] and, above all, changes in building materials []. Originally using local materials such as earth, straw, wood, locust bean pods, stone, etc., builders and beneficiaries in urban and rural areas are increasingly interested in modern materials such as cement [], sheet metal, ceramics, etc. This situation is gradually leading to the deterioration and disappearance of the original traditional buildings, which are places of memory filled with history and messages for present and future generations. From [], earthen constructions are losing ground in Africa to industrial materials. As early as 2000, in its World Report on Monuments and Sites in Danger, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) warned of the growing threat of degradation and disappearance of various types of heritage, including vernacular heritage, especially in war-torn and developing countries. Throughout the world, and especially in Africa, there is a wide variety of monuments, historic villages and towns, family homes, archaeological sites, etc., which are in the process of changing, deteriorating or disappearing, and which are of economic, ecological and social importance to their communities and make a positive contribution to the local economy. In full and strong urban transition [,,], Africa’s traditional buildings are gradually disappearing and undergoing radical change [].

The gradual disappearance of traditional dwellings observed throughout the world is a particularity in Togo. According to the fifth (5th) General Population and Housing Census (RGPH-5, 2022), housing in Togo is dominated by the traditional type (42%), followed by the semi-modern type (31%) and the modern type (27%). A summary analysis of this data shows that semi-modern and modern housing (58%) outnumbers traditional housing. Traditional Togolese housing is therefore in the throes of degradation and change.

In the urban area of Kara, traditional architecture is undergoing the effects of time and socio-temporal change. The puddled earth used to build traditional walls is increasingly giving way to mud bricks, mixed or not mixed with cement. Straw gives way to sheet metal, and wood to metal. The same applies to the broken pottery in the courtyard and the compacting of soil in the rooms, which have been replaced by ceramics, cobblestones and washed concrete. Community and social work are increasingly giving way to individual work. These traditional materials, all the know-how and traditional building techniques that are one of the beauties of Togo and the urban agglomeration of Kara, are in the throes of change. Considered indigenous, the Kabyè are the majority people in this geographical area. For the purposes of this study, the traditional habitat of the urban agglomeration of Kara is the traditional habitat of the Kabyè people.

With this in mind, the main objective of this article is to analyze the traditional habitats of the urban agglomeration of Kara in the wake of socio-temporal changes. Specifically, the aim is as follows: (i) to list the different traditional architectural styles of the urban agglomeration of Kara following socio-temporal changes; and (ii) to present the characteristics of each type of traditional habitat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

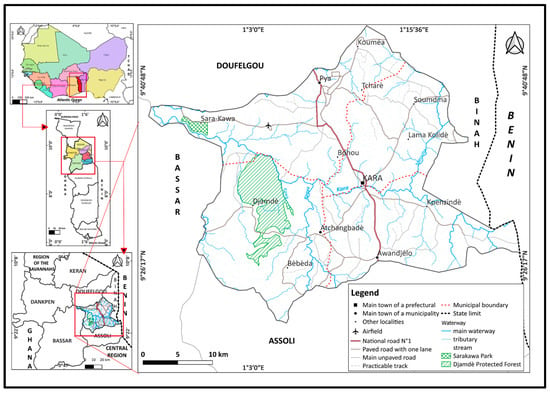

The study area, the urban agglomeration of Kara, is located in Togo, West Africa. It is situated in the northern region of the country. It lies between 9°30′ and 9°45′ north latitude and 1° and 1°15′ east longitude, with an average surface area of 1075 km2, and is mainly populated by the Kabyè (people who consider themselves indigenous to the place). Other ethnic groups such as the Tem, Lamba, Nawdéba, etc., and foreigners are also found in the locality. It is bordered to the north by the Doufelgou prefecture, to the south by the Assoli prefecture, to the east by the Binah prefecture and the Republic of Benin, and to the west by the Bassar and Dankpen prefectures. Administratively, with an estimated population of 283,738, the prefecture of Kozah is made up of one hundred and ten (110) villages grouped into fifteen (15) cantons (INSEED 2022) and structured into four (04) communes, namely the commune of Kozah 1 with Kara as its administrative center, the commune of Kozah 2 with Pya as its administrative center, the commune of Kozah 3 with Awandjélo as its administrative center, and the commune of Kozah 4 with Atchangbadé as its administrative center. The town of Kara is the capital of the Kara region, the capital of the Kozah prefecture and the capital of the Kozah 1 commune. In the context of our study, the urban agglomeration of Kara is made up of the town center, which is the commune of Kozah 1, and the outskirts, which are the communes of Kozah 2, Kozah 3 and Kozah 4. It can therefore be assimilated into the Kozah prefecture, as shown on Scheme 1. The human occupation of the Kabyè, the majority and presumed indigenous people of the study area, is the consequence of a long-standing settlement process. This ancient process can be understood through two diametrically opposed interpretations. The first stems from the descent of the first Kabyè man from the sky, while the second locates the origin of the people in migratory phenomena.

Scheme 1.

Geographical location of the urban agglomeration of Kara. Source: INSEED, 2022 modified Author.

2.2. Research Methodology

This research is based on a mixed methodology that combines quantitative and qualitative data. It also draws on secondary and primary data.

2.2.1. Documentary Research

Existing data were provided by documentary research, which was of vital importance to this study. It enabled us to take stock of the research question, define the scope of the study and identify the issues and challenges faced by other researchers. It was based on the reading of general and specific works, theses, dissertations, reviews and articles to better define the contours of the theme. This led us to documentation centers such as the national library in Lomé, the central library of the University of Lomé and of Kara, the Research Laboratory on the Dynamics of Environments and Societies (LARDYMES), the National Institute for Statistics and Economic and Demographic Studies (INSEED) and the African School of Architecture and Urban Planning library (EAMAU). We also visited online research sites related to our research topic. All this documentation made it possible to reframe the research topic and to have the necessary resources to support this research.

2.2.2. Observation

As a preliminary investigative tool for all research, observation enabled us to grasp the realities relating to the research problem. It enabled us to take stock of the architectural heritage and to analyze the situation in a participatory manner. In the field, we were able to observe traditional building forms, construction styles and the cohabitation of traditional and modern buildings, building materials and construction techniques. These observations made it possible to reframe the research subject and establish the research findings. Observation also involved taking pictures and images to illustrate scientific reasoning. The observation phase took place during the entire data collection process of the pre-survey, which was conducted from 5 to 9 February 2024, and the survey from 12 to 24 August 2024.

2.2.3. Interviews

Interviews were conducted using an interview guide. The interview guide was used to collect the qualitative data required for the research. Institutions such as the regional directorate of culture, the regional directorate of planning, the four (04) communes of the urban agglomeration of Kara, the manager of the Kara Museum and traditional chiefs were interviewed. Table 1 shows the interviews conducted during this research. These are the people available to provide information related to the research topic. Discussions and interviews with resource persons, i.e., traditional chiefs and village elders from Tcharé, Lassa, Yadé, Bohou, Kouméa, Pya and Lama, neighborhood chiefs, traditional priests, traditional masons, managers of the technical services of the four (04) town councils (DST), the mayors of the four (04) communes, chiefs of cantons and villages, managers and directors of the Yadè traditional museum and the Kara regional museum, the regional director of arts and culture for the Kara region, and the regional director of planning for the Kara region provided the information needed to write this article. The canton of Lama had more interviews with resource persons, while in the other cantons, questionnaires were administered to households in addition to a few interviews.

Table 1.

People identified for interviews.

2.2.4. Questionnaire-Based Survey

Quantitative data were collected from household surveys using a questionnaire guide. This approach made it possible to obtain data on the characteristics and types of traditional dwellings in the area. It also provided information on wall construction materials, roofing materials, the size and number of rooms in the concessions, the average surface area of rooms and concessions, the reasons for choosing a settlement site and the actors involved in building traditional houses.

- Sampling technique

- To determine the sample to be surveyed, the following formula was adopted:

- N: P/T

- N: Number of households

- P: Target population

- T: Average household size

The average household size used in this study is 5 persons per household, in line with the results of the fifth General Population and Housing Census (RGPH-5, 2022). The sampling rate used is 1/75. The total number of households surveyed was 327, distributed according to canton. The data were collected using the Kobocollect software (ODK Collect v2024.2.4). The unit used for the survey was the chief of the household. He or she may be represented by a third party, depending on convenience and availability. The chief of the household is the most appropriate person to intervene in household decisions and to master the contours of the research problem around housing and building choice. The choice of households to be surveyed was made at random, according to the availability of the heads of households to answer the questionnaires. Architectural surveys and sketches enabled us to reconstruct the habitat types. GPS coordinates of traditional settlements were taken for a better cartographic representation of the different types according to the classification criteria retained. Table 2 summarizes the households surveyed.

Table 2.

Households surveyed.

For the purposes of this study, and on the basis of the pre-survey, interviews, field surveys and literature review, the following classification criteria were adopted, such as the construction and roofing materials and the shape of the room (round, square or rectangular). In total, three types of traditional house were categorized in the study area, in accordance with the field surveys and data processing, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Categorization of traditional house types according to classification criteria.

2.2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

To analyze and interpret the quantitative and qualitative data obtained in the field, the data collected was processed using the S.P.S.S. V 29.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 29.0) software, which has the advantage of handling large sample sizes and producing simple tables and cross-tabulations. Word was used for text processing and editing. Graphics were produced using Excel. Mapping software programs such as Autocar and ArcGIS were used to produce maps. Sketches were made by hand with pencil and eraser.

3. Results

The traditional habitat of the urban agglomeration of Kara derives from daily use, forms of belief and the degree of economic development of the area. It is distinguished by its originality in terms of the shape of the rooms, spatial organization, local building materials and implementation techniques. Over time, this type of habitat has evolved in terms of shape, construction materials and roofing materials, giving rise to two (02) additional types of traditional habitat, in addition to the original one.

3.1. Type 1: An Original Habitat Marked by Round Rooms Made of Puddled Earth and Straw Roofing

3.1.1. Composition and Spatial Organization of Buildings

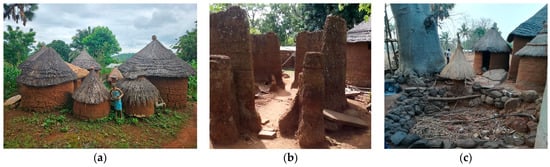

In Africa, the habitat unit is not usually a compact building concentrating several functions, but rather these activities are carried out in small units distributed around a courtyard []. The original traditional habitat of the urban agglomeration of Kara is composed of a central courtyard around which are grafted rooms intended for various functions. Figure 1 shows in (a) an overview of the original traditional Kabyè dwelling in the urban agglomeration of Kara, in (b) two (02) giant clods of earth averaging 1.5 m in height framing the house entrance and in (c) an open mini-pit averaging one meter (01 m) in depth, a sizeable space that is an integral part of the original traditional Kabyè concession located at the front of the house. The results of field surveys show that this is a space intended for keeping animals, generally goats, under the visual control and vigilance of all nearby residents, and which also serves as a place for preparing natural manure for cultivation periods.

Figure 1.

Traditional Kabyè habitat. Source: Auteur, 2024.

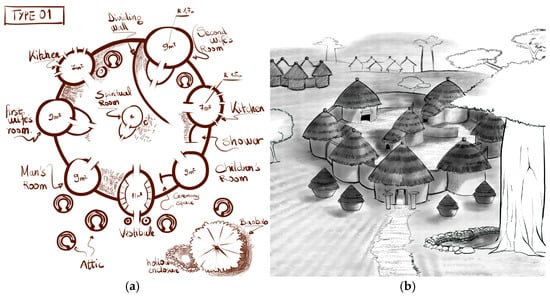

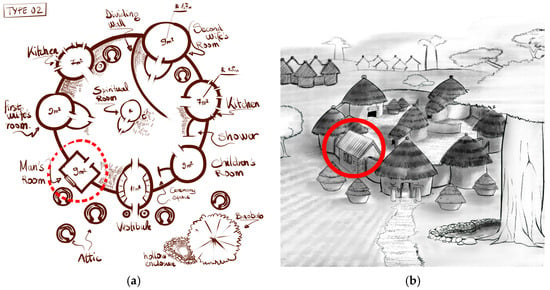

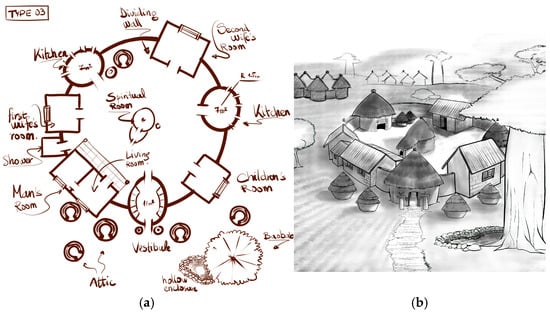

All this, organized in a spectacular and original way, testifies to the ingenuity of the Kabyè builders in the design and implementation of their traditional structures. Figure 2 shows in (a) a two-dimensional view (2d) and in (b) a three-dimensional view (3d) of the original traditional dwelling in the urban agglomeration of Kara, with the rooms arranged around the courtyard. This is composed of a vestibule, rooms for sleeping, kitchens, attics, a shower, a room for deities and chicken coops, all arranged in a circular fashion to form a courtyard in the middle of the house. The Kabyè house has no particular orientation. As shown in Figure 2, the vestibule is positioned to facilitate the entry and exit of the inhabitants. It determines the position of the other rooms.

Figure 2.

2d and 3d view of an original traditional Kabyè house (type 1). Source: Auteur, 2024.

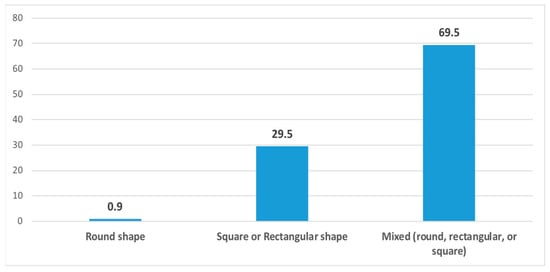

These original dwellings, with their round rooms, are disappearing and being replaced by rectangular or square shapes. Figure 3 shows that 69.5% of respondents live in mixed rooms, i.e., round, rectangular or square, 29.5% in rectangular or square rooms and 0.9% in round rooms. This result shows the extent to which the original round shape has disappeared and been replaced by new shapes such as the square and the rectangle. This mutation is the result of changing lifestyles, galloping urbanization, the growing disinterest of young people and those involved in the construction of traditional buildings, the emergence of new needs and global warming. From [], the major destruction of buildings and historic sites are among the risks to humanity associated with climate change.

Figure 3.

The shape of habitat rooms. Source: Field data, 2024.

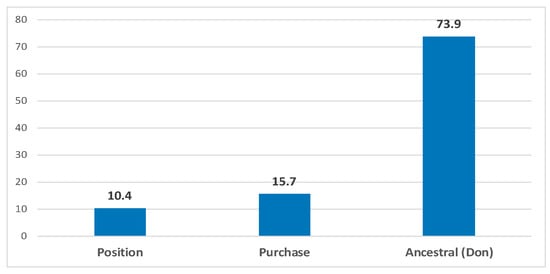

Like all dwellings, the traditional Kabyè house is built on a well-chosen site according to well-defined ceremonies, prayers and rituals. In fact, the choice of site is made from several angles, depending on the position, by purchase or as a donation. Figure 4 shows that 73.9% of sites were acquired by donation, 15.7% by purchase and 10.4% due to the position. These data reveal a shift in land acquisition from customary to modern law. Originally, among the Kabyè people, the land did not belong to humans but to the deities and ancestors, and men only borrow it for their needs (living or farming). Whatever the acquisition formula adopted, the approval of the deities on the site is mandatory and is obtained following well-known ceremonies and rituals. Therefore, solicitation takes the form of well-known ceremonies during which the deities express themselves and give or withhold their approval.

Figure 4.

Choosing a site for building a new home. Source: Field data, 2024.

3.1.2. Traditional Construction Actors

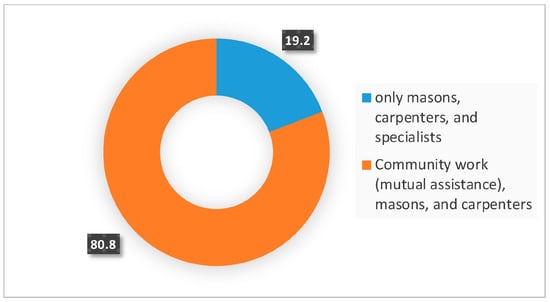

The construction of any human dwelling mobilizes a number of actors according to their skills and knowledge. In the urban agglomeration of Kara, the original traditional habitat is no exception to this rule. In fact, the buildings are built by the entire community through mutual aid, bringing together people of all profiles. Figure 5 shows that the original traditional dwellings in the urban agglomeration of Kara are built by the entire community, assisted by masons and carpenters in a mutual aid scheme. This construction process was confirmed by 80.8% of respondents. The house is built by craftsmen and assisted by the beneficiaries of the work. All the work is done by hand. From [], in traditional African society, there are no specialists for construction. Everyone works for themselves, following virtually unchanging techniques handed down from generation to generation. In this traditional construction, as among the Batammariba, the labor force and time are not binding parameters, yet today they have become very significant. As far as categories of people are concerned, there are no exceptions. All categories, i.e., men, women and children, assist and contribute to the implementation of the work. In addition to the latter, the elderly, deities and ancestors have their share of participation, which is not necessarily physical. Each category plays a specific role. From [], in the construction of traditional African rural dwellings, everyone has a role to play. The man has the essential part; the woman plasters and decorates, and the young people are responsible for transport, especially water by the young girls. The whole chain of work illustrates the solidarity and sociability of the construction industry in the Kabyè region.

Figure 5.

Actors involved in building construction. Source: Field data, 2024.

3.1.3. Building Materials and Techniques

All houses are built using specific techniques and materials. In the urban agglomeration of Kara, traditional Kabyè houses are built using purely traditional techniques and local materials: raw earth, straw and raw wood. Figure 6 shows in (a) earth dug near a building site to a depth of 80 cm to around one meter (01 m), in (b) straw to cover the houses, in (c) wood for the framework and in (d) the successive laying of rammed earth clods. All these show the local materials (earth, straw, and wood) used to build traditional houses and the techniques employed. Indeed, this kneaded earth technique remains the construction technique par excellence. The dug earth is kneaded by hand and feet, successively mixed with water, then shaped into earthen balls and laid in successive layers. Wood and straw are used for roofing and the roof frame.

Figure 6.

Phase of digging the earth and forming clods of earth near a construction site. Source: Author, 2022.

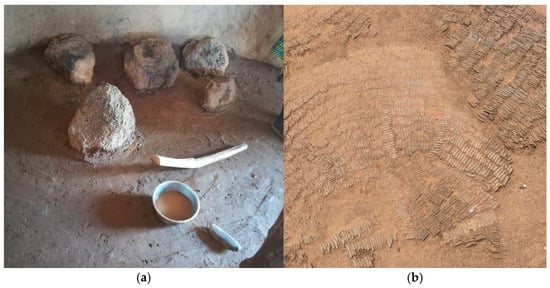

The construction is completed with finishing work such as plastering and smoothing the walls by the women, tamping the floor and paving in broken pottery shards. Figure 7 shows in (a) ground tarmac work in a bedroom and in (b) paving work in a courtyard using broken shard pottery. This technique enhances the view and protects the courtyard from erosion during heavy rainfall. Floor tamping and smoothing in the bedrooms protects the floors and is the final coating applied in these areas.

Figure 7.

Damage to the floor in a room and paving made of broken pottery shards in a courtyard. Source: Author, 2022.

3.1.4. House Decoration

The beauty of a house depends on its aesthetics through decoration and facades. In the urban agglomeration of Kara, builders take aesthetics into account when constructing houses, as confirmed by 67.28% of those surveyed, according to Table 4.

Table 4.

Table showing the rate at which esthetics are taken into account in the construction of traditional dwellings.

The Kabyè decorate their homes with hunting and war trophies, namely the horns of wild beasts and weapons taken from the enemy. Figure 8 shows in (a) and in (b) the remains and horns of animals on the facades of a house, as decoration and spiritual protection against evil spirits. Kabyè house facades are generally very simple. Overhanging roofs protect the walls from the elements and shade the facades. However, with migration, outside influences, the emergence of new needs, the arrival of new shapes such as rectangular and square and the evolution of building materials, the original traditional habitat of the urban agglomeration of Kara has evolved to give rise to two (02) additional types of traditional habitat, in addition to the original, within this geographical area.

Figure 8.

Animal horn decorations on the house. Source: Author, 2022.

3.2. Type 2: Habitat Marked by the Emergence of the Rectangular Shape, and the First Use of Molded Mud Bricks and Steel Sheets for Roofing

An evolved form, type 2, is the first variant, derived from the original. The traditional Kabyè house has developed over the years, under the influence of migration from north to south, and externally with neighboring countries and the rest of the world, as the Kabyè are rightly renowned for their agrarian civilization and rural migration [], with the appearance of new shapes, the evolution of construction techniques from kneaded earth to mud brick and the beginning of the use of steel sheeting for roofing. Figure 9 shows in (a) the two-dimensional view and in (b) the three-dimensional view of the spatial organization of type 2 habitats, illustrating the new shapes introduced and the sheet metal roof. This is the rectangular or square shape, dedicated exclusively to the man’s bedroom.

Figure 9.

Two-dimensional and 3d views of the evolved traditional Kabyè dwelling, type 2. Source: Author, 2022.

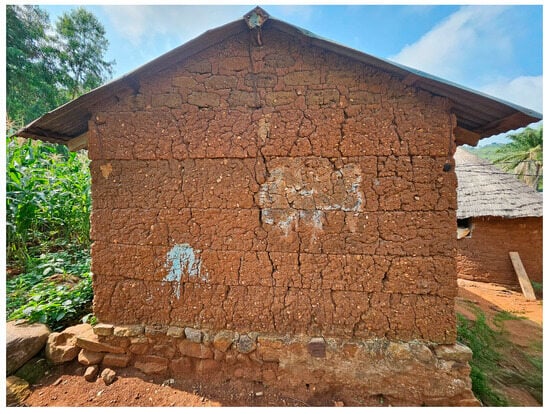

Added to this is the evolution of techniques, marked by the beginning of the use of earth bricks or adobe. Figure 10 shows a model of a traditional Kabyè habitat, type 2, in the villages of Lassa in (a) and Soumdina in (b). This is composed of round rooms, with a rectangular mixed form for the man’s bedroom, built in mud bricks, and covered in steel sheeting. Earthen bricks made from a wooden mold mark an evolution in earthen construction techniques in the urban agglomeration of Kara. This evolution is due to the dynamics and, above all, the commercial and knowledge exchanges between construction workers, the wealthy owners of the time and travelers.

Figure 10.

View of a traditional dwelling, type 2. Source: Author, 2022.

However, for a long time, this new technique, which was little mastered by craftsmen, was rarely used. This type is also marked by the extensive use of rammed earth for the construction of rectangular houses. Figure 11 shows an advanced example of a traditional Kabyè house, with a rectangular shape but with a purely traditional clod wall covered in sheet metal. This confirms the continued use of the kneaded earth technique in spite of the dynamics and reflects the Kabyè builder’s constant attachment to traditional techniques, achievements, origins and know-how. Although the materials and techniques are evolving, the composition, spatial organization, choice of site and people involved in construction remain unchanged from the original style. However, aspects such as openings, the morphological aspect of certain rooms, construction techniques and materials are evolving.

Figure 11.

Rectangular room built of earth and covered with sheet metal. Source: Author, 2022.

3.2.1. The Origin of the Rectangular House: A New Shape Resulting from External Migration

The rectangular house first appeared in the southern part of Togo before independence in the 1960s, following the migrations, voyages and discoveries made by traders and slaves on the continents of Europe, Asia and America. They then discovered the rectangular shape, distinguished by its simplicity and the easiest way to manage the space. Their return home marked the start of a series of changes in habits, lifestyles and ways of living. These changes affected both the daily lives of residents and their know-how. Under the influence of internal north–south migrations, builders and travelers, especially merchants, discovered these changes, in particular the rectangular shape introduced by external migrations. This shape is characterized by its adaptability to new needs. The traditional Kabyè habitat, which in the past was characterized by round-shaped houses, is beginning to undergo a number of changes, with the substitution of the round house for the rectangular house for the man’s bedroom, to embody novelty, evolution, modernism and superiority. At first, this type of home was dedicated exclusively to the head of the family or concession. The latter could easily receive his distinguished guests, set up a table, a lounge, eat his meals, accommodate a modern bed and much more. For a long time, the rectangular shape was a privilege that only the heads of concessions could afford according to their financial means.

3.2.2. Man’s Room or “Laza”: A Round Shape Replaced by a Rectangular One

Commonly known as “Laza”, for the rectangular shape of the man’s room, this replaces the round shape of the man’s room. This is a consequence of migration on two (02) levels, external migration between Togo and the rest of the world, and internal migration between northern and southern Togo. This marks the beginning of the changes observed in the traditional habitat of the Kabyè people of the urban agglomeration of Kara. This involves a new shape for the room and a new way of covering the room. We are now seeing a two-slope roof, with gable walls generally running lengthwise. Straw is the main roofing material, and on rare occasions, when the means are available, steel sheeting is used to match the evolution of the roof with a frame still made of local wood.

3.2.3. Raw Earth Bricks or Adobe: An Evolution in Earth Building Techniques

Described as an indirect construction method, the earth is molded into wooden frames for masonry. Figure 12 shows in (a) a wooden mold and in (b) a mold and mud bricks, also known as molded bricks or adobes. The transition from kneaded clay to molded brick is probably the result of an interior influence, especially between northern and southern Togo, and external influences from neighboring countries (Benin and Ghana). More suited to rectangular shapes, molded bricks or mud bricks appeared in the urban agglomeration of Kara at the same time as the rectangular form. Raw earth brick or adobe is a mixture of clay, water and sometimes plant matter such as chopped straw to increase its strength. From [], the mixing of straw and clay is due to the complementary nature of these two materials. Adobe is therefore a building material made from a mixture of sand, clay and a quantity of chopped straw or other plant fiber. Each element in the mix plays its part. The sand reduces the likelihood of micro-cracks in the earth block, the clay binds the particles together and the chopped straw gives a certain degree of flexibility [].

Figure 12.

Wooden frame and adobe brick. Source: Author, 2024.

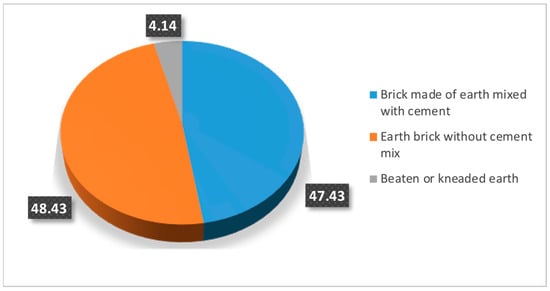

In the urban agglomeration of Kara, mud bricks are widely used. Figure 13 shows, according to the results of field surveys, that 48.43% of buildings are made of uncemented mud bricks, compared with 47.43% made of mixed materials and 4.14% made of kneaded earth. These data illustrate an increasing shift away from the use of kneaded earth, which symbolizes the originality of wall construction, towards more advanced materials, notably mud bricks and cement mixes. From [], knowledge of brick manufacture often preceded the adoption of the rectangular plan. This assertion does not seem to have been verified by the Kabyè when we see that rectangular houses were built using the rammed earth construction technique long before rectangular houses were built using the mud brick technique.

Figure 13.

Traditional wall construction materials. Source: Field data, 2024.

3.2.4. Increasingly Large Room Openings in Response to the Evolution of Living Modes

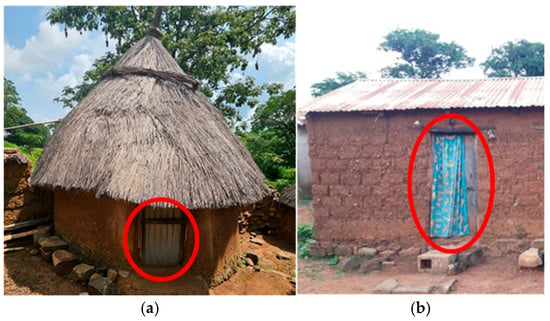

With the mutation from a round to rectangular shape, the change introduced in habits and ways of living, the traditional Kabyè house, particularly the rectangular room, is experiencing an evolution in the size and dimensions of openings, namely doors and windows. From [], the door is a fundamental architectural element that provides access between interior and exterior spaces. With regard to doors, the builder went from small openings where once you had to stoop to enter the house, to man-height openings that made it easier for people to enter and exit without having to make large maneuvers. Figure 14 shows a rectangular room with door openings, with the average dimensions ranging from 80 cm to 90 cm wide and 1.8 m to 2 m high.

Figure 14.

View of the door openings of a rectangular room. Source: Author, 2024.

These openings are larger in width and height than the access openings to the original type of housing, which vary in size from 60 cm to 70 cm wide and 1.5 m to 1.8 m high. Figure 15 shows in (a) the access opening of a round room and in (b) the access opening of a rectangular room, illustrating the difference in dimensions between the two (02) opening shapes.

Figure 15.

View of the various access openings of a round room and a rectangular room. Source: Author, 2024.

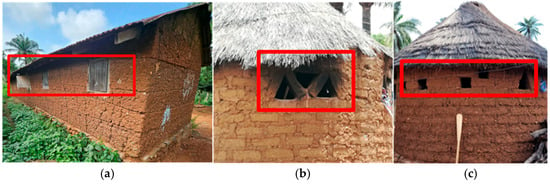

The change in door dimensions can also be seen in the windows, which have gone from dormitory rooms with no windows and kitchen rooms with small triangular or square openings to large rectangular or square openings averaging 80 cm wide by 1 m high, with wooden fastenings for sleeping rooms. Figure 16 shows in (a) the windows of a rectangular room that are larger than the window openings of the original kitchen rooms, in (b) and in (c), marking the evolution in traditional building styles in the urban agglomeration of Kara. All these photos, data and comparisons illustrate the first evolution of the original traditional house of the urban agglomeration of Kara, marking the dynamics observed.

Figure 16.

Comparative view of the window openings in a rectangular sleeping room and the original circular kitchen rooms. Source: Author, 2024.

This first architectural variant, under the constant effect of changing lifestyles and building materials with the arrival of cement and other modern materials, gave rise to a second type of traditional habitat, as follows.

3.3. Type 3: Propagation of the Rectangular Shape and Use of Modern Materials

This type of traditional Kabyè house, the advanced form of traditional housing, is marked by the extensive use of modern materials such as cement and sheet metal, and above all by the intensification of the rectangular shape. Figure 17 shows in (a) a two-dimensional (2d) view and in (b) a three-dimensional (3d) view of the most advanced model of traditional housing in the urban agglomeration of Kara. The strong presence of rectangular rooms illustrates the dynamics of the shapes observed. With its spatial organization virtually unchanged from the original, this house symbolizes the beginning of the modernization of the traditional Kabyè house.

Figure 17.

Two-dimensional and 3d views of the third type of traditional Kabyè dwelling. Source: Author, 2024.

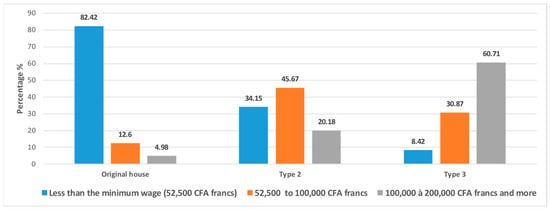

In every society and for thousands of years, access to an evolution has always been reserved for a social category of people, commonly called ‘cadres’, who have a higher income than the average farmer. Figure 18 shows that, firstly, among the occupants of the original habitat, 82.42% of the respondents have a monthly income below the minimum wage (XOF 52,500), while 12.6% and 4.98% of the respondents have a monthly income above the minimum wage. Among type 2 residents, 34.15% and 45.67% have a monthly income below the minimum wage and between XOF 52,500 and 100,000, respectively. Finally, among type 3 residents, 60.71% have a monthly income between XOF 100,000 and 200,000 or more. High monthly incomes facilitate the purchase of modern building materials, which farmers are unable to afford. This would be the reason which explains the low proportion of occupants in the third type. From [], earth building materials are generally less expensive.

Figure 18.

Monthly income of inhabitants of traditional buildings. Source: Field data, 2024.

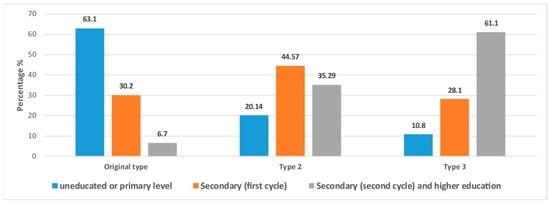

In addition to a high monthly income, occupants of this advanced type have a certain level of education. Figure 19 shows that, according to the field results, 63.1% of the occupants of the original houses have no education or a primary-level education, 44.57% of the occupants of type 2 houses have a lower secondary education and 61.1% of the occupants of type 3 houses have upper secondary education. These data illustrate a strong presence and proportion of the less educated people in the original traditional buildings, while the more educated dominate in the more advanced traditional buildings. This can be explained by the desire and willingness of the educated persons to change and bring something new or modern to the design and construction of their homes. Indeed, the latter, because of their high level of education, are more likely to find a decent job and earn enough money to afford modern building materials. This is not the case for the less educated people, who for lack of education are mostly farmers and craftsmen.

Figure 19.

Level of education of inhabitants of traditional buildings. Source: Field data, 2024.

In terms of materials, the arrival of cement marked a significant change, as cement was mixed with earth to make mud bricks. House roofing switched from straw to sheet metal. As in rural Martinique, the evolution of peasant housing is reflected in a shift from straw to sheet metal for roofing, and as underlined by [], the house is evolving. In the past, the use of straw was a serious improvement. Today, straw is no longer satisfactory. Straw roofing does not last long enough and presents fire hazards, while sheet metal, which breaks the picturesque charm of the room, seems to be a providence in practical life. Transport and installation are easy, the duration is satisfactory, and the small farmer is proud when he builds a house of planks covered with sheet metal, while waiting for something better. Sheet metal is therefore used instead of straw for roofing houses, and cement for making bricks and coating. Figure 20 shows in (a) a rectangular house built of uncemented mud brick, covered in sheet metal, with the beginnings of a cement coating, and in (b) a rectangular house built of uncemented mud brick, lightly coated with cement and covered in sheet metal. Steel sheets are the most common material used.

Figure 20.

Rectangular houses with the use of cement. Source: Author, 2024.

The purpose of mixing cement with earth to make mud bricks is to increase the strength of the bricks. When financial resources permit, it is also used to plaster the inside and outside of the houses. The better-off use cement bricks instead of mud bricks mixed with cement. This represents a change in construction techniques and a modernization of the way people live. These new housing models increasingly call on the services of specialists such as masons, carpenters and sheet metal workers. All this shows the evolution of construction techniques through the specialization of the various persons following the arrival of new building materials. This new chain of actors clashes with the purely traditional models that included all the actors in society, whether experienced or not, with the result that the community, social and mutual aid work observed in the construction cycle of the original traditional dwellings in the urban agglomeration of Kara has disappeared. This actor change marks a significant turning point in the evolution of traditional habitats and lifestyles within the urban agglomeration of Kara.

Decorations, once marked by animal horns and the smoothing of walls with locust bean pods and shea oil, are increasingly giving way to paintings on cement-coated walls.

The composition and spatial organization of the sites have changed very little, demonstrating the great importance attached by the Kabyè to their origins and heritage. The choice of a new building site is always preceded by rituals and ceremonies. Construction stages are closely linked to construction techniques and are undergoing significant change. New techniques for mixing soil with cement have saved time in the search for soil. The fact that earth was no longer mixed with water alone, but also with cement to increase the strength of the bricks, marked the beginning of a considerable reduction in the quantity of earth used by the Kabyè builder. Buildings grow more easily and more quickly thanks to cement, which has good resistance and hardens more quickly than simple earth [].

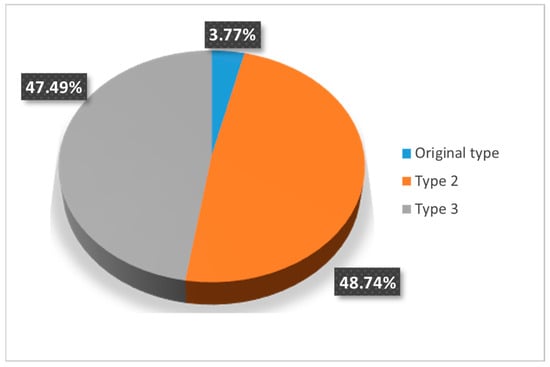

From the original style to the changes observed in traditional housing in the urban agglomeration of Kara, the spatial organization, ceremonies to choose the building site and composition of the dwelling remain strongly rooted in the Kabyè builder’s use of space. The gradual disappearance of the original habitat is a fact of life in this geographical zone, and is being strongly replaced by the derivative types described above. Figure 21 shows a representation rate of 3.77% for the purely original style, compared with 48.74% for type 2 and 47.45% for type 3. These data show a strong substitution of modern forms of housing to the detriment of the original form. The rapid disappearance of the original traditional habitat in the urban agglomeration is increasingly worrying, and is leading to the disappearance of know-how and social values.

Figure 21.

Distribution of different types of traditional habitats. Source: Field data, 2024.

4. Discussion

Traditional housing in the urban agglomeration of Kara derives from daily use, forms of belief and the degree of economic development of the area and its occupants. Through their creative diversity, traditional Kabyè builders have made their mark through their ingenuity in designing and constructing traditional dwellings using materials from their environment. In fact, the Kabyè builder paves his courtyard with shards of broken pottery, which allows him to decorate and protect his space against erosion caused by the region’s heavy rains. The research work of [] highlights broken pottery floor coverings in Togo, and more specifically in northern Togo, in the Kabyè region. It underscores the aesthetic appearance of this coating, as well as its resistance over time. These are coatings that can last up to a century. Raw earth, the main material used to build the original traditional dwellings of the urban agglomeration of Kara, is a historic material that has been used for thousands of years and since the standardization of men. From [], it is one of the oldest building materials in the history of man, and its high representation on the World Heritage List (20% according to UNESCO) bears witness to the world’s rich earthen architectural heritage. This view is also shared by [], which states raw earth has been a building material for over eleven millennia, and today, earthen architectural heritage is universally spread across all inhabited continents. Ref. [] joins this idea by presenting the exceptional character of certain significant elements of the architectural and landscape heritage of ancient African societies. Earthen architecture is an important part of this heritage, and is represented by constructions of quality that date back thousands of years and have stood the test of time, such as the earthen mosques of Mali (Djenné, Tombouctou, and Gao) and the Toloy granaries (2nd–3rd century). Raw earth has very interesting thermo-hygro-mechanical properties, which can help reduce the environmental impact of buildings from the construction phase through to their entire lifespan []. The earth used to build the original Kabyè habitats is clay, available on the construction site and obtained by digging to a given depth near the site. It is processed using the kneaded earth technique. The Tamberma tatas, who live in the same region as the Kabyè, use the same soil-finding process and construction technique. From [], the technique for shaping clay is almost the same in all African countries. The earth used in Koutammakou is mainly clay. It is taken from the building site, and the mason does not have to travel far to find it. The same applies to the wood and straw used in the roofing and framing of houses. Evolving lifestyles and living habits, strong population growth, rapid urbanization and the emergence of new building techniques and materials such as sheet metal and cement have brought about considerable changes in traditional Kabyè housing. From the technique of kneaded earth came the technique of earth bricks without a cement mixture, then earth bricks with a cement mixture, and cement bricks, used for building walls. Additionally, there was an evolution from round to rectangular shapes and the use of sheet metal as roofing material. These changes have given rise to two (02) types of traditional housing in addition to the original within the urban agglomeration of Kara. From [], the use of sheet metal instead of straw is the result of a normal process of evolution and improvement in occupant safety. This paper states sheet metal roofing is not only a source of pride for the small-scale farmer who can afford to use it to cover his house, straw roofing is also too short-lived and presents fire hazards, whereas sheet metal is more resistant, longer-lasting and easier to install. These changes can also be seen in the traditional Bamiléké habitats in western Cameron. From [], the straw roof of traditional Bamiléké houses has been replaced by a corrugated metal sheet roof as traditional housing has evolved. These results are also supported by the research work of [], which states that confrontation with the way of life, and in particular the Western lifestyle, generated by colonization, triggered far-reaching changes in the traditional habitat of the Ksourians of the Ziban region. Cement is used in the construction of traditional dwellings to reinforce structures and protect homes against rapid deterioration, as this material offers good mechanical performance and rapid hardening. This also reduces construction times. This hypothesis is supported by [], which explores the reasons behind the use of cement in home construction and its impact on occupant comfort. The results show that cement is widely used in the Kara region because of its technical properties of strength, rapid hardening, time-saving and aesthetic appeal. This choice is also linked to the availability of financial resources, as underlined by []; people build different types of residential buildings according to their purchasing power. This view is also shared by [] which, in research on the evolution of the rural habitat and its becoming in the Central Rif, distinguishes three (03) types of rural housing as the traditional type for low-income earners, the mixed type for middle-income earners and the modern type for the local bourgeoisie.

5. Conclusions

This study on the dynamics and types of traditional dwellings in the urban agglomeration of Kara catalogs and presents the architectural characteristics of the traditional buildings of the Kabyè people, who consider themselves indigenous to this geographical area. Based on the evolution of shapes and building and roofing materials, three (03) traditional habitat types have been identified, namely type 1 or the original style, consisting of round houses built with purely local materials such as raw earth, wood and straw. Then, a second type derived from the original is characterized by a shift of the form through the introduction of the rectangular or square shape and an evolution of the construction technique from kneaded earth to mud brick. Finally, a third type is marked by the intensification of the rectangular or square shape and the arrival of cement to make bricks, as well as the use of sheet metal instead of straw. From the original to the third variant, the ceremonies for choosing the site of a new building and the morphology of certain rooms such as the spiritual room, the kitchen and the attics remain unchanged. However, the evolution of construction techniques from kneaded earth to earth bricks mixed with cement or cement bricks, the replacement of straw by sheet metal, and the replacement of tamping in bedrooms and paving in courtyards with shards of broken pottery, respectively, by cementing and ceramic cladding in rooms and cement screed in courtyards, mark significant changes and contribute to the disappearance of the social values of the communal living, community work and mutual aid that are one of the beauties and pride of the Kabyè people. All this is contributing to the disappearance of cultural and social values in the urban area of Kara. Urgent action is needed to help safeguard the heritage, especially the architectural heritage, of the urban area of Kara. These discoveries have significant implications for understanding the factors and level of disappearance and degradation of the original architectural heritage, as well as the mutations observed in this geographical area. Given the limited existing documentation on the architectural heritage of this geographic area, further research is essential to highlight and document the immense cultural, artistic and architectural richness of the urban agglomeration of Kara, particularly in the face of rapid urbanization and its consequences. This research could look at interactions between towns and countries from the perspective of safeguarding cultural heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A.A.K., M.B. and C.C.A.; methodology, G.A.A.K. and M.B.; software, G.A.A.K. and M.B., validation, G.A.A.K., M.B. and C.C.A.; formal analysis, J.T. and C.C.A.; investigation, G.A.A.K.; resources, G.A.A.K.; data curation, G.A.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.A.K.; writing—review and editing, M.B., J.T. and C.C.A.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.B., J.T. and C.C.A.; funding acquisition, G.A.A.K. and C.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the World Bank through the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERVIDA-DOUNEDON), funding number IDA 5360 TG or 6512-TG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors declare that this study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of CERVIDA-DOUNEDON at the thesis stage of the 2023–2024 academic year.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The necessary data are contained in the article. For any additional data relating to this study, requests should be sent to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the World Bank and the University of Lomé (UL) via the Regional Center of Excellence for Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERVIDA-DOUNEDON) for their financial contributions and scientific supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dejeant, F.; Garnier, P.; Joffroy, T. Matériaux Locaux, Matériaux D’avenir. CRAterre. 2021; 96p. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03293589 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Huret, J. Quel avenir pour les constructions en terre crue dans les campagnes d’aujourd’hui? Le cas de la Communauté d’Agglomération du Mont Saint-Michel Normandie. Géographie, 2019, 157. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02375892v1 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Cisse, A. Quelle Perception de L’architecture Traditionnelle Africaine Aux Yeux de la Nouvelle Génération? In Proceedings of the Terra Lyon 2016, Lyon, France, 10–14 July 2016; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Elamé, J.E.; Landry, T.T.N. La Concession Familiale Bamiléké: Un Exemple D’architecture Endogène au Cameroun. Can. Geogr./Géogr. Can. 2023, 67, 304–315. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cag.12804 (accessed on 19 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Attab, S. Amélioration de la Situation de L’habitat Traditionnel Collectif Dans un Quartier Ancien à Guelma [Mémoire de Master 2]. [Guelema]: Université 8 Mai 1945—Guelma. 2021. Available online: https://dspace.univ-guelma.dz/jspui/handle/123456789/11556 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Laouar, D. Etude D’une Rétrospective Historique de L’habitat: Le Bati Residentiel Traditionnel du Vieux Mila Comme Reference Dans la Production de L’habitat [Mémoire de Magister]. [ALGERIE]: Ferhat Abbas-Setif. 2018. Available online: http://dspace.univ-setif.dz:8888/jspui/handle/123456789/2816 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- David, G.; Leticia, D. Patrimoine Mondial: Inventaire de I’architecture de Terre; CRATerre-ENSAG: Grenoble, France, 2012; 280p, ISBN 978-2-906901-69-8. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000217037 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Fabbri, A.; Morel, J.C.; Gallipoli, D. Assessing the Performance of Earth Building Materials: A Review of Recent Developments. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2018, 3, 46–58. Available online: https://letters.rilem.net/index.php/rilem/article/view/71 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- BTPAfrique. Architecture Africaine: Un Savoir-Faire Ancestral. BTP Afrique. 2021. Available online: https://btpafrique.com/2021/04/23/architecture-africaine-un-savoir-faire-ancestral/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Brasseur, G. L’habitat Rural Africain à Grands Traits, Etudes Scientifiques, 1975, 10. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/pleins_textes_7/b_fdi_55-56/010022593.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Hubert, G. Architecture de Terre: Histoire, Culture et Société; UNIVERSITE PIERRE MENDÈS FRANCE DE GRENOBLE: Grenoble, France, 2007; Volume 3, p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Fiefonou, D.A.A. Architecture Bioclimatique Dans Six Principales Villes du Togo, In Revue Habitat et Ville Durable2023; Volume 1, pp. 92–104. Available online: https://www.eamau.org/?page_id=2710 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Marguerat, Y. L’architecture populaire ancienne à Lomé, Editions Haho, 1991, 7. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers17-06/010028873.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Rauss, R. Le Pays Kabié: Les Vertes Collines de L’AFRIQUE de L’ouest. 1998; pp. 189–205. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/globe_0398-3412_1998_num_138_1_1399 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Alavi, S.F.; Tanaka, T. Analyzing the Role of Identity Elements and Features of Housing in Historical and Modern Architecture in Shaping Architectural Identity: The Case of Herat City. Architecture 2023, 3, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossim, M.J.; Aholou, C.C.; Ayité, Y.M.X.D. The Contribution of Earth Bricks Reinforced with the Aqueous Maceration of Néré Pods (Parkia biglobosa) to Sustainable Construction in Togo: Characterization, Formulation, Mechanical Performance, and Recommendations. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguigah, D.A. Archéologie et Architecture Traditionnelle en Afrique de L’ouest: Le Cas des Revêtements de Sols au Togo: Une Étude Comparée. 2018; pp. 1–277. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/it/resources/an/4788143 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Jonathan, K.; Johannes, N.M. Le Dynamisme Architectural en Zone Rurale: Cas des Palais Royaux de la Région de L’ouest–Cameroun. Chapitre D’ouvrage. 2023; pp. 99–345. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/114397761/LE_DYNAMISME_ARCHITECTURAL_EN_ZONE_RURALE_CAS_DES_PALAIS_ROYAUX_DE_LA_R%C3%89GION_DE_L_OUEST_CAMEROUN (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Philokyprou, M. Continuities and Discontinuities in the Vernacular Architecture. Res. Gate 2015, 1, 111–120. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329107381_Continuities_and_Discontinuities_in_the_Vernacular_Architecture (accessed on 16 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Kuipers, M. Acknowledging the Dignity of Architectural Heritage Adding a Fourth Virtue to the Vitruvian Triad. Res. Gate 2023, 9, 257–280. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372020895_Acknowledging_the_Dignity_of_Architectural_Heritage_Adding_a_Fourth_Virtue_to_the_Vitruvian_Triad (accessed on 19 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Donfack, K.; Aurélien, Y. Evolution de L’habitat Traditionnel en Afrique. Exemple de la Province de L’ouest au Cameroun [These]. [Berlin]: Université technique de Berlin/Technischen Universität Berlin. 2011. Available online: https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/items/urn:nbn:de:kobv:83-opus-33510 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Tossim, M.J.; Tombar, P.A.; Banakinao, S.; Mavunda, C.A.; Sondou, T.; Aholou, C.C.; Ayité, Y.M.X.D. Analysis of the Choice of Cement in Construction and Its Impact on Comfort in Togo. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koita, F. L’art en Afrique|PDF|Afrique|Environnement Naturel. 2021; p. 3. Available online: https://fr.scribd.com/document/489649897/L-art-en-Afrique (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bank, A.D. Dynamiques de l’urbanisation en Afrique 2022—Le Rayonnement Économique des Villes Africaines. African Development Bank Group; 2022, p. 205. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents/dynamiques-de-lurbanisation-en-afrique-2022-le-rayonnement-economique-des-villes-africaines (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Antoine, P. L’urbanisation en Afrique et ses perspectives, In Aliments dans les Villes, 1997, 21. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9c0aee9f-3eee-436e-ae14-9a19bcb19c70/content (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Escallier, R. La croissance des populations urbaines en Afrique. Quelques éléments D’introduction. 1988; pp. 177–182. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/espos_0755-7809_1988_num_6_2_1262 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Rosa Latapie, S.; Abou-Chakra, A.; Sabathier, V. Bibliometric Analysis of Bio- and Earth-Based Building Materials: Current and Future Trends. Constr. Mater. 2023, 3, 474–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillet-Schwartz, A.M. Aménagement de L’espace et Mouvements de Populations au Togo: L’exemple du Pays Kabyè. Cah. D’études Afr. 1986, 26, 317–331. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1986_num_26_103_1705 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chaib, H. Contribution à l’Etude des Propriétés Thermo-Mécaniques des Briques en Terre Confectionnée par des Fibres Végétale Locale. (Cas de la ville de Ouargla) [Thesis]. [ALGERIE]: Universite Kasdi Merbah—Ouargla. 2017. Available online: http://dspace.univ-ouargla.dz/jspui/handle/123456789/13967 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Seignobos, C. Les Transformations de L’habitation Traditionnelle au Tchad: Du Cercle au Carré. 1971; Volume 24, N95, pp. 294–324. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/caoum_0373-5834_1971_num_24_95_2591 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Çelik, O.; Bideci, A. Material and Design Analysis of Doors in Traditional Düzce–Konuralp Architecture. Architecture 2025, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegun, O.B.; Adedeji, Y.M.D. Review of Economic and Environmental Benefits of Earthen Materials for Housing in Africa. Front. Archit. Res. 2017, 6, 519–528. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2095263517300547 (accessed on 24 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Denise, C. Une Histoire Évolutive de L’habitat Martiniquais. Situ Rev. Des Patrim. 2004, 5, 11. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/insitu/2381 (accessed on 26 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mango-Itulamya, L.A. La Construction en Terre Crue. Raw Earth Construction. 2019; p. 15. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/237179 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Anger, R. Approche Granulaire et Colloïdale du Matériau Terre Pour la Construction [phdthesis]. INSA de Lyon. 2011. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-00735722 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Amoussou, G.K. La Transmission du Savoir-Faire Lié à la Construction de L’habitat Traditionnel «Takienta» et Son Impact Sur la Conservation Du «Koutammakou» du Togo [Mémoire de Maîtrise des Sciences Appliquées (M. Sc. A.) en Aménagement, Option Conservation de L’environnement Bâti]. [Montréal]: Université de Montréal. 2008. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1866/8240 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Sriti, L.; Tabet-aoul, K. Evolution des Modeles D’habitat et Appropriation de L’espace. Courr. Savoir Sci. Tech. 2014, 5, 23–30. Available online: https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/77934 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ma, X.; Wang, T. Research on the Traditional Architecture Types of Huai’an Canal. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 287–292. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=104419 (accessed on 19 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Boudouah, M.; Mimouni, N. Evolution de L’habitat Rural et Son Devenir Dans le Rif Central (Senhaja Sraîr). TIDIGHIN 2016, 5, 13. Available online: https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/TIDIGHIN/article/view/8029 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).