Abstract

The atmosphere of an interior space within an architectural built form can be defined by the interactions between the material and immaterial elements surrounding the inhabitant of a space, expressed through our own responding embodied experience. These psychologically tangible yet often immaterial experiences are deeply embodied, realised through our interconnected visual perception, haptic engagement, auditory characteristics, temporal movement and thermal comfort. The study questions how we can harvest useful data to explore atmosphere as an “in-between” state between perceiver and surroundings, through aligning physical environmental recordings with felt personal responses over parallel time-based studies. The approach explored analyses a set of existing spaces through the harvesting of sensory elements using on-site, temporal recordings and participatory haptic engagement. Physical presence is recorded through measured environmental data and audited through a theoretical stance of “conservation of mass”, as each extracted element is replaced and balanced by the other sensorial elements, supporting a holistic experience. Evolving thinking around design approaches promoting an awareness of atmospheric sensibilities can ensure that we do not lose the rich opportunities that sensory design can provide for contemporary architectural design practice. Harvesting atmospheres seeks to describe the broad, elemental nature of sensory design, defining examples of real-time temporary, elusive boundaries and fluid domains that shift spaces between atmospheric experiences, whilst supporting the interconnected collage of the “in-between” complexity of designing with this realm.

1. Introduction

This study aims to reveal the possibilities of intuitive atmospheric approaches to architectural design processes through the study and measurement of real-time spatial atmospheres. As a designer’s intuitive design approach is driven by the articulation of a personal, embodied understanding of atmospheres, this study measures elements of environmental conditions. It seeks to define different atmospheric modalities and record haptic personal responses to the perceived atmosphere to understand better how we perceive boundaries between atmospheres (as transitions between atmospheric modalities).

Significant research in the field of atmospheres discusses the ontological relations between the inhabitant of a space and their surrounding atmosphere [1,2,3,4,5]. Bohme [6] defines atmospheres as “experienced in bodily presence in relation to persons and things in spaces”. Rauh [4,5] theoretically purports to these co-existing relationships between inhabitants and their spatial environments as a “coming together of perceptual components”, described as “the whereby”. This “web of environmental qualities and sensitivities” [4], influenced by the embodied co-presence or co-existence we experience in an interior space, affects our perception of the particular atmosphere at an individual level in an inherently embodied way.

To explore this phenomenon using a “designerly” [7] approach, the following study of the examination and collection of environmental data from a series of rooms in a natural working environment with real “passers-by”, recorded in real time in parallel timeframes, seeks to add to the current conversation by introducing the opportunities of designing with “atmospheric boundary” parameters. It explains how these temporal environmental registers, formatted as environmental data and user responses, can assert a place within the known complex web of data and embodied presence [1] that an interior atmosphere encompasses. The study therefore first questions how we can harvest useful data to explore atmosphere as an “in-between” state between perceiver and surroundings through aligning physical environmental recordings with felt personal responses over parallel time-based studies. It queries whether environmental sensitivity “band widths” can be found or established. It further questions the value of this approach and its usefulness to designers seeking to define or conserve an atmospheric state. The study describes a series of scenarios where the findings posit a change in atmosphere may occur. And, finally, it invites us to reflect on designing for atmospheres as fluid domains, through negotiating “interrupting”, disruptive elements and developing a heightened awareness of perceived responses to our ever-changing surrounding environments.

2. Materials and Methods

In gathering and collecting data, this study seeks to harvest tangible, quantifiable measures, represented as numerical values found within the selected spatial environments, “rooms”, alongside concurrent participant qualitative interactions and responses. This approach to harvesting data allows for the collection of environmental background readings that have been “maturing” as more static elements within this given architectural space and are now available for extraction, in addition to the layers of temporal elements, with expected fluctuations in readings and sporadic disruptive events. In essence, the harvesting exercise seeks to extract from the spatial atmosphere a variety of constituent parts defined through the recording of a set of selected sensory elements through parallel relational qualitative interactions, seeking to satisfy a holistic viewpoint and relational ontology.

2.1. The Room—A Theoretical Perspective and Approach

Ottolini, in Canepa [8], states that, “The room is a very small part of the architectural score”. However, we know that any room is the defining spatial volume and atmospheric void within which we interact directly with our environment and surroundings. The room is therefore the critical medium between building (or architectural score) and inhabitant when studying atmosphere. The character of a room and its atmosphere can vary from an unconscious and underwhelming experience to a conscious and stimulating (a positive or negative) reaction to a particular space. It provides an embodied relationship to our spatial and environmental surroundings when we engage with it.

The room, If defined as the space surrounding us, Is composed of material components that can all be physically described, each one in turn, as “physical and physiological” [9]. The room that the atmosphere inhabits is formed of a variety of interconnected elements, “endowed with thickness, consistency, weight and materiality” [8]. The physical boundaries of the room, if defined by atmospheric volume, are, however, more challenging to determine. Pallasmaa outlines the complexity of this construct that we experience in our surroundings, proposing that, “The boundary line between the self and the world is identified by our senses” [10].

Our physical “presence” is therefore required within the room to assimilate this atmospheric information through an engagement with our senses and support any boundary conditions we propose. These boundaries are, however, often temporal, and consequently difficult to capture and record as their limits become elusive. Our sensory awareness may stretch to hearing sounds from an adjacent room or external context to a macro fixed focus gaze, harnessing our visual attention on light hitting a textured wall, within arm’s reach.

This fluidity of atmospheric volume highlights the challenge of the research environment. The confines and containment of an atmosphere in a space are therefore unrealistic to determine over a longer period of time, but are rather, if expected to be unpredictable, in a state of flux and generally elusive, only determined by the inhabitant of the space and the physical and atmospheric presence within their surroundings that they are reacting to. The void created by the physical, sometimes impermeable, sometimes permeable, walls, ceiling and floor is the space within which the human inhabits, and our understanding of how to capture, or “see” [11], the space as a fluctuating environmental condition is paramount in understanding more about the atmosphere and the integrated, embodied elements it carries.

2.2. Conservation of Mass in Atmospheres—A Methodology

The law of conservation of mass as a scientific theory refers to a process associated with chemical reactions. It works within a closed system (where no matter can enter or exit) where the total mass, after any reaction, equals the total mass before the reaction took place. The atoms are rearranged further in the reaction as part of the chemical process, but are not destroyed or multiplied, just changed in form. This theory aligns closely with our current understanding of human perception as the bio-regulatory reactions responsible for emotions and the associated effects of physical and neurological stimuli on our sensory regulation processes.

Applying the theory of conservation of mass to an analysis of atmospheric conditions within an architectural space demands a new application of theoretical thinking and a new identity for the space or “room”. Formed by a particular ontological perspective, it provides a rationale for the definition of agreed boundaries or confines of the experimental space and, most importantly, ensures that we capture “the nuanced and fleeting nature of the atmospheric event” [8], or reaction.

Working with the theory of conservation of mass and an aligned ontological approach to data harvesting of atmospheres within interiors, the following approaches can be considered. First, each harvested physical element is conceptually removed momentarily, as it is recorded as a physical attribute and manifestation; the other elements balance out to fill this void temporarily, creating a shift in the balance of the elements but allowing the void of the “in-between” to provide the continuum of the atmosphere. The continuum of the atmosphere is then limited to background “noise”, as each element is extracted with a series of interruptive events being recorded as perceptual changes.

Each individual element is therefore required to combine together, to work holistically, to allow us to assemble a wider picture of the situation and the particular atmosphere perceived. This second approach aligns with Canepa’s [8] discussion of Luhmann’s [12] description of atmosphere as a “kind of excess effect caused by the difference”, affecting the “sensory-perceptive spectrum of the spatially immersed individual” [8]. In this case, it is proposed that atmospheric understanding can be unravelled and advanced through the following:

- Measuring, collecting and analysing physical environmental parameters of a set of specific places, within specific timeframes;

- Using a broad range of numerical measurement methods in tandem with a qualitative, participatory approach;

- Recording of participant’s reactions to a perceived atmospheric change—a physical change indicator button to record atmospheric “difference” between one referenced moment of time and another.

2.3. Material Harvesting—Sensory Elements and Their Physical Attribution

Giere’s [13] perspective on scientific realism and instrumentalism adds to the discussion of appropriate methodologies for recording the physical attributions and characteristics of atmosphere. He proposes that scientific assertions are “analogous, they are assertions about how the world is, from this theory, or using this instrument”. Brown [14], an expert in the aligned field of colour philosophy, proposes that Giere’s [13] approach challenges our assumptions of scientific measurement, to question if there really can be a “unique, unified description of the world” that is the “real” one.

Rauh [4] reiterates an alignment with this question and further develops the discussion by highlighting that what “is perceived and thus what stimulates perception” is not “determined solely” by “acoustically perceived tone sequences in a certain decibel strength, different intensities of light of different wavelengths”, the temperature in a room and other environmental and sensory factors. He notes that we must not forget personal perception through feelings or mood. Bohme [6] proposes that these feelings define our perception of the “atmosphere” and are required to mediate the “objective factors of the environment with aesthetic feelings of a human being”.

The investigation and interrogation of atmosphere as a whole therefore cannot be a simple measurement exercise of environmental factors in a set of rooms, but, as Canepa [8] notes, requires to be the sum of all “affective qualities identifying a place that engages us in a state of resonance and attunement” [8], embracing sensorimotor, emotive and cognitive processes. This research investigation thus explores a set of sensory elements as key environmental indicator readings to reveal the environmental elements providing the most valuable data for extraction for the analysis of atmosphere. In parallel, the framework invites the qualitative study of human emotive and cognitive perceptions of changing temporal atmospheres within a selected set of interior spaces.

2.4. A Framework for Harvesting Sensory Elements

A selection of sensory components were identified to include a broad variety of quantitative environmental measures to permit the harvesting of as many useful sensory elements as possible, assumed to be generators, carriers or amplifiers of atmospheric character.

- A distance range for visual and acoustic recordings was also considered to support key explorations and definitions of the atmospheric boundary without limiting the collection of key contributing factors influencing the atmosphere’s character. Distal and/or proximal measurements were included for each sensory value type, with both included where practical and appropriate.

- Visual Perception—distal and proximal: Harvested data include photographic recording, background lighting levels and further layers of light as illuminance values and as luminance contrast studies, recorded in both the horizontal working plane and physical vertical boundary elements (walls, doors, windows, digital screens).

- Haptic Engagement—proximal (not included in the scope of this study beyond engaging with a table and chair in the experimental location and a clicker via a “silent” mouse).

- Auditory Characteristics—distal and proximal (sounds within the space, adjacent spaces and from the exterior environment measured in “Decibels relative to full scale”—dBFS).

- Temporal Movement—of external factors only, not encouraged for the participant, to ensure continuity of the experimental format and focus on the chosen task. Tasks selected were participant’s personal choice, all desk-based (as required by the spatial furniture arrangement), and the subsequent physical body movements varied accordingly to suit.

- Thermal Comfort—distal only (again, proximal not included within the scope of this study but recommended for further study).

In addition to the experimental protocols being agreed upon, the measurement devices were then tested in the chosen environment before the experimental event as a data collection pilot study to test the experimental process. With successful test readings completed, the experimental set-up was defined, and it was decided to have the devices/monitors/sensors temporarily fixed in chosen, relatively hidden locations, for the duration of each research event. Phones, sensors and/or cameras were used to provide synchronous, parallel data and instantaneous sets of results, to limit experimental error and to support a short set-up time with background recording running as unobtrusively as possible.

The following android apps were used to record audio and acoustic measurements: “Spectroid” (real-time spectrum analyser measuring and displaying frequency and intensity using Fast Fourier Transform), “Audio Recorder” and “Sound Spectrum Analyzer”.

Lighting illuminance values were measured using 2 x calibrated light meters and the android 2025 version of the “Fusion Optix” app for luminance spot values and luminance contrast images. Illuminance, temperature (wet bulb and dry bulb) and wind flow were measured using a Kestrel 3000 33673 & Lutron LM-8000 (The University of Edinburgh Bookit store, Edinburgh, UK.) Anemometer.

“Flir One Pro—iOS” (Apple Ipad version) thermal imaging software was used with the Apple Ipad camera to ascertain thermal temperature values and visual imaging. The sensor was kept within the advised operating temperature range.

Photographs and videos were collected before the sessions to record the physical context, experimental set-up, spatial volumes and colours, using Sony Experia, Canon Legria HF M506, Nikon D5600 DSLR +18–55 mm Lens (Sony, Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. “Room” Selection and the Value of the “Passer-By”

“Atmospheres prevail wherever spaces are experienced—albeit with varying intensity and obtrusiveness” [4]. A set of existing spaces were selected for the research study to allow participants to experience the spaces and support the intuitive understanding and definition of participants’ own levels of intensity or obtrusiveness they perceived within the space.

To ensure useful responses to the research aims, the experimental set-up required a set of environments where specific events could provide sensations through which a perceived change in atmosphere would occur. The selected spaces are located in University buildings in the centre of Edinburgh. They were chosen to ensure they did not convey the feeling of experimental test laboratory spaces, but rather, during the experimental event and data collection process, they would function with their normal purpose, as individual study and group meeting spaces for staff and students in the University. It was hoped that the popularity and the subsequent consistent demand for use of these selected spaces would benefit the research project two-fold: through reasonably high footfall to provoke interest and “passers-by” (participants) to engage with the research, and through the popularity of the location and type of study space available to use if participating in the research event. Participants were notified of the event with a poster noting the experimental set-up and data recording protocols, located adjacent to each test event room. This information invited any University staff or students to participate who wished to use the space for study, research or other self-focused academic activity. Although any University staff or student member could participate, the research data were expected to have a reduced general applicability due to the limitations of demographic diversity of the participant pool and the identification of pre-existing hypo/hyper-environmental sensitivities.

Through maintaining the intended use of the space use, the study sought to encourage participants to feel comfortable and familiar in a location they frequented often to complete these academic tasks. This experimental set-up sought to avoid forced or predetermined results, which could be the research outcome if using a space specifically designed by the researcher to evaluate environmental factors, or, through experimental set-up, force un-natural or assumed outcomes. The design or insertion of a specifically designed experimental space generally faces challenges as any new interventions/space designs would expect to have difficulty initially naturally fitting into the surrounding context. Rather, by using “real” spaces, the study could seek to address the atmosphere of the selected spaces with a reduced intrusion into the normal environment the participants would expect to find in these locations. Without these distractions, it was anticipated that the study could support a different emphasis and focus.

The experimental set-up included two separate rooms that were used by different participants simultaneously. Room 01 was an internal room with three “enclosing” red walls, functioning as a single study space, located off the main corridor thoroughfare; see Figure 1a–c. Room 02 was located on the third floor, in the East wing of the same building, see Figure 2a,b.

Figure 1.

(a) Room 01 viewed from the front; (b) Room 01 viewed in the context of the adjoining corridor; (c) Room 01: the view out of the space into the adjacent corridor and panelled wall of study lounge.

Figure 2.

(a) Room 02 viewed from inside; (b) Room 02 viewed in the context of the adjoining corridor space, with research event space on right.

Room 02 was considerably larger, providing windows with views to the exterior street, classroom seating and vertical digital screens at the end of each table and on the four fixed walls in the room. Room 02 had a door which was left open ajar, as it had been found prior to the experimental set-up.

3. Results

Pre-Event Collection of Participant Information

All participants entering either room were given a QR code link to a short, anonymous questionnaire to fill in on their mobile phone prior to entering the space to provide information on the following:

- Their previous location—External for 20 min or more/internal another building/internal same building;

- Their “current feeling about their surrounding environment”—open ended descriptive text box required completion, with a maximum of 20 characters;

- The task they would do in the space—from a choice of the following: urgent work/digital work/physical writing or drawing/reading/phone call/play game on phone/meditate/not sure yet;

- The length of time they needed to complete their chosen task—2 min/5 min/between 5 and 10 min/more than 10 min.

Participants were then given a space to sit in the chosen room with a computer mouse, and, as per the initial experimental test instruction sheet outlined, each participant was asked to click the mouse when they felt the “atmosphere of the space was different”.

A total of 25 adult participants were recruited to take part in the testing for Room 01, of which 22 had previously used the space before at least once. Participants spent between 6 and 12 min (mean = 8 min) in the space, and the study produced approximately 4.5 h of video and 1 h of 1–2 min bursts of audio recordings. Participants chose to work on a quick email, study or use their mobile phone in the space, with most noting in the starting questionnaire that they were planning just to complete a quick task.

The Room 02 research event recruited 14 adult participants over three separate mornings. In total, 3 of the 14 participants had used this room before. Participants spent between approximately 18 to 35 min (mean = 26 min) in the space; the study produced approximately 2.5 h of video and 55 min of 1–2 min bites of audio recordings. Participants entering Room 01 were asked to stay no longer than 10 min to allow others to participate. Before entering Room 02, participants were told they could stay up to 30 min in the room. All participants were told they would not be observed and that they would be reminded when their time was over. Ten participants described the work they needed to do as “urgent” and would take “more than 10 min” to complete.

As participants were sitting in the rooms, the following measurements were recorded and have been summarised below for Room 01 in Table 1 and Room 02 in Table 2.

Table 1.

Room 01 recorded data of element measurement range.

Table 1.

Room 01 recorded data of element measurement range.

| Sensory Element | Light | Sound | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Type 1 | Horizontal illuminance values peaked at 410 Lux on the working plane (table). Band-width variation of ± of 10 Lux under artificial illumination conditions. | Acoustic measurements— recording of background sound—band-width between 28 and 48 dB + additional transient sounds, seen as spikes in Figure 3. | Steady-state band-width between 21 and 22 degrees Celsius recorded at all wall surfaces. No fluctuations over the time periods recorded. |

| Measurement Type 2 | Vertical illuminance values taken on the face of the stone wall at the threshold of the room were 205 Lux. On the panelled wall visible from the space, the reading recorded approximately 256 Lux as a fixed value. Band-width variation of ± 5 Lux. | Sound recordings were collected in short bursts between 1 and 5 min duration, starting as soon as the participant entered the room. Maximum background sound readings were recorded as 48 dB, with the majority of sound recorded within lower frequencies, average of 38 Db, varying band-width of −10 dB. | See Figure 4a,b for visual representation of thermal recordings using Flir measurement app. |

| Measurement Type 3 | Luminance values for both the internal room walls and the adjacent surfaces are shown in Figure 5a,b. | Spikes in sound aligned with sounds from the lift as people entered and exited with the call bell indicator creating high frequency spikes to 75 dB. |

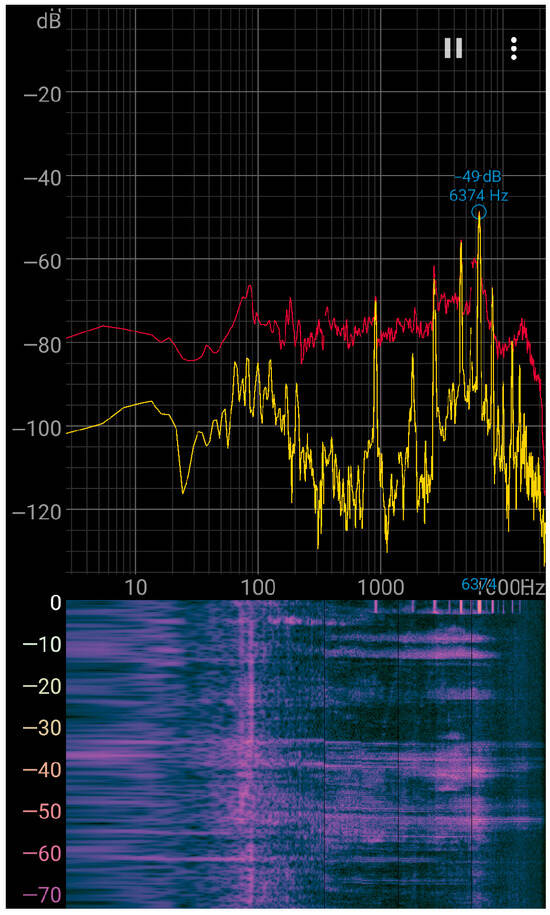

Figure 3.

Acoustic recording in Room 01 with “Spectroid” app showing disruptive sound patterns in yellow, with previously highest maximum sound recording level in recorded session shown in red.

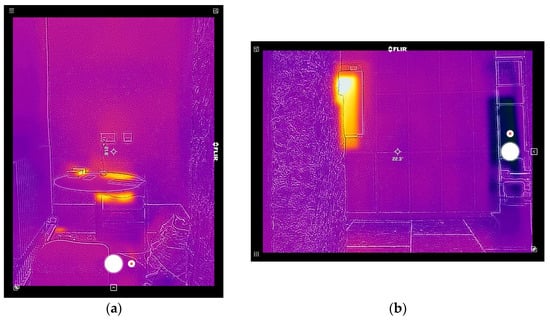

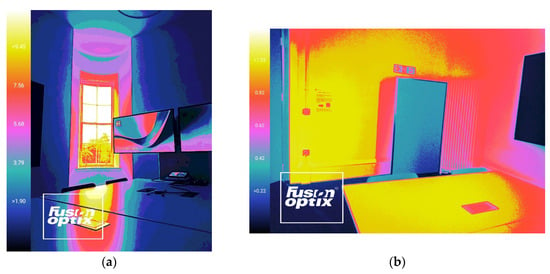

Figure 4.

(a) Room 01 Flir One Pro image showing wall temperature within the room. (b) Room 02 Flir One Pro image showing wall temperature on the panelled wall across the corridor from the room with the digital screen reaching +50 degrees Celsius.

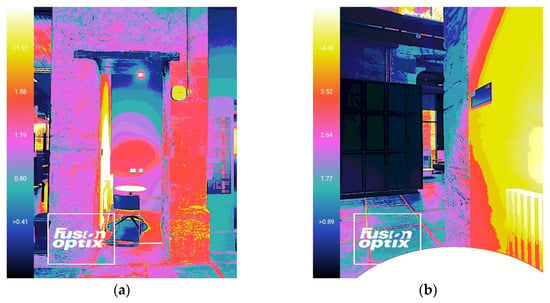

Figure 5.

(a) Room 01 Fusion Optix image showing lighting contrast within the room—brightness ratio 1:10 is significant and shows the high brightness conditions the table area receives. (b) Room 01 Fusion Optix image showing the lighting contrast in cd/sqm on the panelled wall across the corridor from the room with lighting contrast between the adjacent side, internal wall of the room and the panelled wall across the corridor reaching 1:20. This contrast indicates a high-brightness situation with discomfort glare expected.

An example screenshot from the sound recording using the “Spectroid” app is shown above. The spikes in high frequency sound are shown in both the data table and the frequency of the acoustically disruptive events in the lower image, which also captures and expresses time-based patterns (Figure 3). The band-width variation in sound in this location extended to almost 50 Hz of variation.

Table 2.

Room 02 recorded data of elements measurement range.

Table 2.

Room 02 recorded data of elements measurement range.

| Sensory Element | Light | Sound | Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Type 1 | Horizontal illuminance values peaked at 190 Lux on the working plane (the table/desk). | Acoustic measurements— recording of background sound varied between 28 ± 10 dB due to additional transient sounds from the exterior road traffic. | Steady-state between 17 and 18 degrees Celsius recorded at the window and 28 degrees Celsius at the digital screens. No fluctuations over the time periods recorded. |

| Variation of ± of 5 Lux under daylighting illumination conditions. | |||

| Horizontal illuminance values peaked at 190 Lux on the working plane (table). | |||

| Measurement type 2 | Vertical illuminance values taken on the face of the walls of Room 02 varied between 695 Lux on the walls surrounding the window to less than 200 Lux on the walls to the rear of the participant. | Frequency of recording—sound recordings were collected in short bursts between 1 and 5 min duration, starting as soon as the participant entered the room. | See Figure 6a,b for visual representation of thermal recordings using Flir measurement app. |

| Measurement Type 3 | Luminance values for the room walls and the adjacent surfaces are shown in Figure 7a,b. |

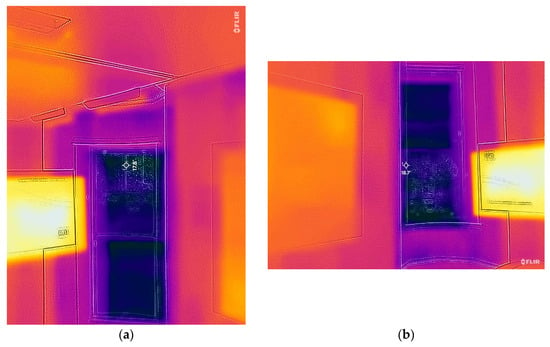

Figure 6.

(a) Room 02 Flir One Pro image showing wall temperature within the room viewed from the table towards the ceiling. (b) Room 02 Flir One Pro image showing wall temperatures within the room viewed from the table towards the window with digital screens on either side.

Figure 7.

(a) Room 02 Fusion Optix image showing lighting contrast within the room—brightness ratio 1:10 is significant and shows the high brightness conditions caused by the corner window. (b) Room 02 Fusion Optix image showing the lighting contrast in cd/sqm on the walls to the rear of the participant. This light indicates a possible balancing out of lighting levels perceived as light is coming from all directions.

4. Discussion

Findings from the correlated results harvested from two different ontological understandings, the scientific physical elemental environmental measures recorded at the same time as the physiological element of the activated “click” initiated by the participant, have shown to be useful approaches for defining moments of atmospheric change. There are limitations of the study in relation to the single selected building typology, however, and a further repetition of this recording approach in other settings would be of value to add to the existing data set and inform design interventions in other spatial contexts.

The recorded “feeling”, or unspoken “interoception” [15], of the participant at the start of the research event, alongside the participant’s response to a previous physical location, has revealed connections that would benefit from further investigation. Almost all participants who noted they had previously been (working/studying or eating) in the building prior to the event were less engaged in the task of “clicking” the mouse. They rarely interjected with a “click” during the session and verbally commented that nothing had changed during their time in the space. Those who had been elsewhere, in another building or in an external environment, showed a heightened sense of curiosity and interacted enthusiastically with the task, clicking more frequently. This amplified awareness of their perceived atmospheric condition, due to the changing “affective states” [16] of their “psychophysiological mode” [15], was particularly evident in participants in Room 02. This room had very few fluctuations in measurable environmental conditions, as can be seen in the band-width variations in the results, yet had the most participant engagement.

The study highlighted some factors that influenced the atmospheric experience of the participants. Visual changes occurring through the window in Room 02 did not result in changes to the atmosphere at all, but auditory changes from the same location did seem to affect the participants’ perceived atmosphere.

Measurements through the “conservation of mass” allowed the researcher and participant to question the nature of our heightened emotive awareness and focus when specific interrupters break into the currently perceived atmosphere and change our cognitive focus from one element to another. The speed of each measurable environmental change was a significant component in the participant sensorimotor “click” action. Short bursts of high-frequency sound or sudden lighting changes (luminance—lighting contrast levels) as people walked past proved to be significant interrupters of the atmosphere.

These findings suggest that the theoretical use of the “conservation of mass” as a recording methodology can provide practical design approaches in relation to the atmospheric disrupters revealed in the results. In designing spaces, we can assume that minor changes to environmental conditions happening over a period of 20 min or more will have less impact on perceived atmospheric changes than interrupters that are temporary and short, with a larger band-width, activating an instantaneous change and an extended spatial boundary condition. During the point of activation of an “interrupter”, the boundary is elusive, as the space is defined by the farthest source of elemental measure: distant changes in sunlight and clouds through glazed apertures, the movement of people disrupting visual continuity or peripheral sounds.

These quantitative findings and participant perceptions support the challenge many experts in the field of theoretical atmospheric research predict. The interrupting elemental changes were temporal and transient, stretching the boundaries of the atmosphere with them [17]. The boundary of the atmosphere became elusive and difficult to define. Griffero [18] notes that, “the more positively active” the atmospheres are, “the more they are evanescent”. The atmosphere, when broken by significant changes in sound, light, participants’ own digital devices or personal thoughts, changed to become a new experience, with the participant and their environment as a holistic entity [19,20]. The constant change for some was noted as “refreshing”, but for others the unpredictable and often temporary change in the nature or character of the atmosphere proved to be unsettling through a sharpened sense that was punctuated by significant interrupters as “sounds, textures, and movements” [21]. Although beyond the scope of this study, further research into prolonged or repeated exposure to these “interrupters” would be valuable to ascertain their significance in atmospheric perception. Canepa [8] proposes that it is the surrounding architectural environment, with its many “voids and fulls”, that “stages the atmospheric artifice—coordinating different sources of emotional expression—that combine together to create a unitary spatial effect”, or atmosphere [3,4,5].

Future research on the fleeting nature of atmospheric events would permit the further definition of atmospheric boundaries through recording environmental elements beyond the selected space. With a distal lens recording the surrounding environment beyond the room, the boundaries of elusive atmospheres might be successfully harvested and our understanding expanded.

Funding

The University of Edinburgh.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Edinburgh 13 June 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Further raw data are available for access by contacting the author directly or https://doi.org/10.7488/ds/8051.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the University for access to the Edinburgh Futures Institute where this study was carried out.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaalama, K.; Fagerholm, N.; Julin, A.; Virtanen, J.-P.; Maksimainen, M.; Hyyppä, H. Sense of presence and sense of place in perceiving a 3D geovisualization for communication in urban planning—Differences introduced by prior familiarity with the place. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B. Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canepa, E.; Scelsi, V.; Fassio, A.; Avanzino, L.; Lagravinese, G.; Chiorri, C. Atmospheres: Feeling Architecture by Emotions: Preliminary Neuroscientific Insights on Atmospheric Perception in Architecture. Ambiances 2019, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, A. The Atmospheric Whereby: Reflections on Subject and Object. Open Philos. 2019, 2, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, G. Atmospheric Architectures: The Aesthetics of Felt Spaces; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bohme, G.; Thibaud, J.-P. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres (Ambiances, Atmospheres and Sensory Experiences of Space); Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, E. Architecture is Atmosphere; Mimesis International: Sesto San Giovanni, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morava, A.K.; Fischer, O.W. Precisions: Architektur Zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst = Precisions: Architecture Between Sciences and the Arts (TheorieBau = Theorybuilding; Bd. 1); Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J.; Zambelli, M. Inseminations: Seeds for Architectural Thought; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zevi, B.; Barry, J.A. Architecture as Space: How to Look at Architecture, Revised ed.; Da Capo Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Art as a Social System (Meridian, Crossing Aesthetics); Stanford University Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giere, R.N. Scientific Perspectivism, Paperback ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.H.; Macpherson, F. The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Colour (Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy); Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S.N. Interoception and emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettieri, G.; Calce, R.P.; Giraudet, E.; Collignon, O. Visual Experience Shapes Bodily Representation of Emotion. Emotion 2025, 25, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments: Surrounding Objects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Griffero, T. Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces; Ashagte Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: Architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C. Experimental atmospherics: A multi-sensory perspective. Qual. Mark. Res. 2022, 25, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K. Atmospheric Attunements. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2011, 29, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).