Abstract

Daylighting is essential in residential building design because it influences energy efficiency and visual comfort while also supporting occupants’ health and overall well-being. Adequate natural light exposure aids circadian regulation and psychological restoration and enhances indoor environmental quality. This study examines how the window-to-wall ratio, skylight-to-roof ratio, and building orientation in a selected low-rise residential building can be optimized to ensure sufficient daylight in warm-humid climates. Using on-site illuminance measurements and climate-based simulations, the daylight performance is evaluated using metrics such as useful daylight illuminance, spatial daylight autonomy, and annual sunlight exposure. Results indicated that a 5% skylight-to-roof ratio (such as a 1:2 skylight setup), combined with a 22% window-to-wall ratio and glazing with a visible transmittance of 0.45, provides a balanced improvement in daylight availability for the chosen case study. The selected configuration optimizes spatial daylight autonomy and useful daylight illuminance while keeping annual sunlight exposure within recommended levels based on the surrounding building landscape. The findings emphasize the importance of tailoring daylighting strategies to site-specific orientation, glazing options, and design constraints. The approach and insights from this case study can be beneficial for incorporating into similar low-rise residential buildings in warm-humid contexts. Incorporating daylight-responsive design into urban and architectural planning supports several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3, 11, and 13).

1. Introduction

Daylight utilization in buildings improves occupant comfort, supporting visual and mental health [1,2], while reducing reliance on energy resources and promoting conservation [3]. Because lighting accounts for a major share of India’s electricity use, effective daylighting strategies are critical for minimizing reliance on artificial lighting [4,5]. Urbanization places a valuable strain on infrastructure and increases pollution and urban heat [6], making proper daylighting to deliver quality illumination and reducing glare-free energy use [7]. In tropical buildings, daylighting is fundamental to most functions [8]. Optimal daylight use reduces energy consumption, but excessive daylight can be counterproductive, emphasizing the importance of efficient architectural design for net-zero buildings [9,10,11].

Building orientation strongly influences sunlight exposure and airflow, highlighting its significance in design [12]. Window-to-wall ratio (WWR), glazing, window placement, orientation, and air-conditioning modes also substantially affect energy performance [13,14]. Higher WWR increases energy use but improves daylight access [15], and a moderate ~30% ratio can minimize overall consumption [16]. Glazing selection is essential in tropical climates, where minor adjustments significantly improve daylight quality and visual comfort [17]. Technologies such as reflective glass and polycarbonate roofing enhance efficiency in warm, humid regions, while well-planned building design, including courtyards and atriums, further improves daylighting and occupant well-being [18,19,20]. Atriums enhance daylight and ventilation in deep-plan buildings and can reduce energy use across climates [21,22]. However, poor daylighting leads to reduced visibility, discomfort, increased thermal gain, and increased energy use [23]. Glare-related anxiety is common in tropical climates [24], and excessive heat and glare may negate daylighting benefits in air-conditioned buildings without proper controls [25]. Glare indices also influenced comfort in window-rich homes, where roof design affects efficiency [26]. Analytical models and daylighting technologies remained essential for estimating exterior daylight parameters and guiding design [27], especially in warm, humid regions where limited research on residential daylight performance under overcast skies exists.

Recent studies have explored technological advancements in tropical daylighting, including dynamic louver shading systems for double-skin facades [28], which improve thermal comfort, reduce cooling loads by 26.2%, and enhance daylighting by 24.76%, including a 6.25% increase in spatial daylight autonomy (sDA). Reviews highlight fiber-based systems, light pipes, and solar concentrators, with Fresnel lenses noted for their lightweight, cost-effective design [29]. In Malaysian offices, double-laminated monocrystalline photovoltaic glass reduces lighting energy consumption by up to 80%, with over 30% of the floor area achieving daylight factor (DF) 1.0–3.5% [30]. Additional research showed that the task-to-medium luminance ratio strongly affects daylight satisfaction and complexity [31]. Organic phase-change materials in double-pane glazing improve thermal comfort, energy efficiency, and daylighting in Vellore and Delhi, reducing solar heat gain by 238.96 kWh and 208.5 kWh, respectively [32]. Psychological studies reported that artificial light is perceived as uniform and suitable for tasks, while daylight with window views improves physiological responses, supporting reductions of 5% in blood pressure and 3% in heart rate [33].

Courtyard building forms in Indian hospitals improved daylight autonomy by 15–20% and reduced energy consumption by 10–15%, emphasizing climate-responsive design [34]. Passive fiber-optic daylighting systems can deliver ≥180 lux with sDA of 85% and >80% uniformity, reducing energy by up to 30% while minimizing glare in windowless interiors [35]. Thermochromic glazing in elderly apartments in Changsha lowered energy use by up to 40%, increased useful daylight illuminance (UDI) by 27%, and improved Circadian Stimulus by 15%, enhanced sleep quality and circadian alignment [36]. Daylighting strengthened links between performance and sustainability by improving visual comfort, reducing energy demands, and supporting health [37]. Integrating daylight-sensitive design into urban planning helped evaluate progress toward the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, 11, and 13 [38,39], with precise light-exposure measurements aiding resilient, low-impact development [40]. A study on elevator retrofits in aging Beijing communities showed that accessibility improvements must balance daylight, ventilation, noise, and visual quality, and offer decision frameworks for sustainable retrofits [41].

Passive cooling and daylighting retrofits for rural Ugandan dwellings achieved up to 47% energy savings through low-cost combinations such as shading, fiber-optic daylighting, and reflective roofs [42]. Urban-morphology analyses emphasized orientation (25.6%), WWR (19.0%), and building height (14.0%) as key energy-related metrics, with insulation, FAR, and aspect ratio also impacting thermal performance [43]. Common indicators such as density, plot ratio, street-canyon ratio, verticality, and height difference show negative correlations with solar access. In contrast, height, shape factor, WWR, building spacing, and sky-view factors are positively correlated [44]. Despite increasing research on daylighting technologies, few studies have simultaneously examined architectural parameters such as WWR, skylight-to-roof ratio (SRR), and orientation for residential buildings in warm-humid regions.

Most existing studies focus on commercial and institutional buildings, leaving a clear gap in understanding passive daylighting strategies for low-rise residential settings in warm-humid climates. This study fills that gap by evaluating daylight performance in a single-story home using an integrated analysis of three key architectural parameters, such as WWR, SRR, and orientation. Unlike previous research that examines these variables or technologies separately, this study combines field illuminance measurements with climate-based simulations to assess their combined effect. The resulting quantitative thresholds not only validate traditional passive design principles but also offer localized, data-driven guidance for architects designing in warm-humid environments.

The present study is divided into four sections. Section 1 discusses the significance of daylighting in residential buildings. Section 2 outlines the experimental and simulation methods used. Section 3 presents the key research findings. Section 4 reviews the main results, discusses limitations, and offers potential recommendations. Section 5 summarizes the main findings of the investigation for future academic research.

2. Materials and Methods

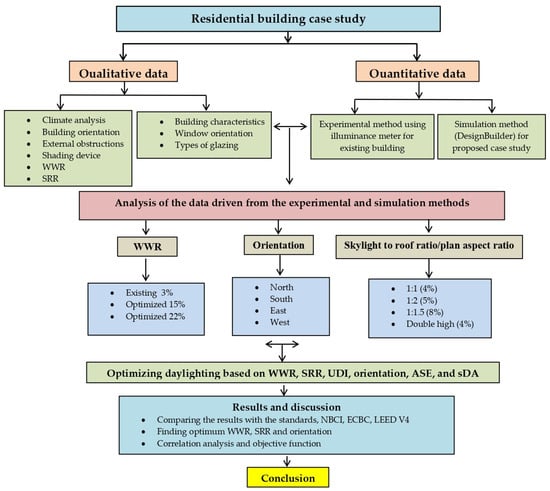

A single-story residence in Chennai is selected for analysis and enhancement of its daylighting performance, based on real-site conditions and dimensions. The examination of climate, topography, orientation, and external obstruction was conducted within the framework of qualitative approaches. The first method involved using an illuminance meter; indoor and outdoor illuminance readings were taken at a 0.8 m work-plane height at 9:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m. in September [45]. As per the National Building Code of India (NBCI) 2016 requirements, grid points within each room were established using the Room Index method, and the DF was calculated from recorded illuminance values and benchmarked against NBCI [46]. On-site measurements were supplemented by the second method simulation modeling using DesignBuilder (Radiance engine) with precise inputs for building geometry, material reflectance (50% walls, 70% ceiling, 20% floor), and glazing characteristics, visible light transmittance (VLT) of 0.45, solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) of 0.25, and overall heat transfer coefficient (U) of 1.5 W/m2K [47]. EnergyPlus was used to obtain Chennai weather data (2009–2023) [48]. After creating a baseline model, the simulation tested iterative variations in WWR (3%, 15%, 22%), SRR (4%, 5%, 8%, and a double-high 4% well), four cardinal orientations, and proportional external shading devices with a projection factor of 0.5 times the window height. Three climate-based daylight performance metrics—sDA, UDI, and annual sunlight exposure (ASE)—aligned with LEED v4.1 requirements were used to evaluate each iteration. The correlations between these parameters were examined using correlation analysis to see how WWR, SRR, and orientation affect daytime behavior. Finally, weighted scores (0.4 for UDI, 0.3 for sDA, and 0.3 for glare-free area [1–ASE]) were assigned to determine the optimum balanced arrangement. Figure 1 illustrates the study’s methodology.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive overview of the research methodology utilized in the research.

2.1. Qualitative Methods

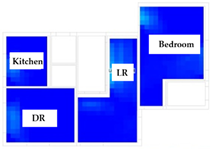

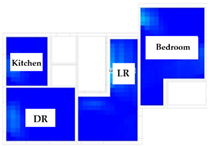

As mentioned above, the study was conducted in a single-story residence located in a low-rise area not exceeding 15 m in height, in a warm and humid climate as per NBCI 2016. The chosen single-story residence reflects the prevailing low-rise style in Chennai, characterized by narrow plots, closely packed neighboring buildings, and low WWRs. Figure 2 shows the house’s blueprints. It is occupied on the ground floor. Surrounding residential buildings are located on the east and west sides of the north-facing unit.

Figure 2.

A test-case single-story residential building.

The house’s physical features are detailed in Table 1. Windows in the current building face all directions, allowing daylight and solar radiation to enter. There is greenery on the western and southern sides of the building, which is enclosed by a compound wall. Windows, skylight performance, and VLT were evaluated separately.

Table 1.

The physical characteristics of the ground floor space.

2.2. Quantitative Methods

Two quantitative techniques were employed to analyze different daylight metrics, such as sDA, UDI, and ASE, for various WWR, orientations, and SRR: the simulation method using DesignBuilder [47] and the experimental method utilizing an illuminance meter.

2.2.1. Experimental Method Using Illuminance Meter

The technique used to distribute illuminance, as well as the surrounding environment, significantly impacts an occupant’s visual tasks [49]. Therefore, adherence to the illuminance standards mandated by NBCI is essential. The illuminance meter measures each illuminance value. The room index formula was used to calculate total points for assessing illuminance, in accordance with the NBCI guidelines. Measurements were taken at a work plane height of 0.8 m from the floor, and indoor and outdoor illuminance were measured using an illuminance meter [46]. The values were recorded at three specific times—9:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m., and 3:00 p.m.—during September. Since it is a Warm-humid climate, the sky is typically overcast, reflecting the region’s typical sky condition [45]. Although the field measurements were taken on a single representative overcast day, the baseline simulation showed good agreement with the observed illuminance levels, providing sufficient confidence in the model’s reliability for evaluating the WWR, SRR, and orientation variations using DesignBuilder as well. From the study and the existing literature, it is observed that room illuminance intensity varies with orientation, obstructions, and window area. The quality of illuminance also differs between rooms [50]. Additionally, illuminance levels vary across the ground-floor rooms due to significant differences in morning, daytime, and afternoon conditions.

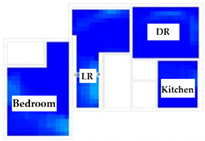

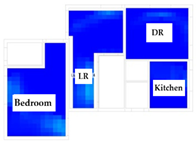

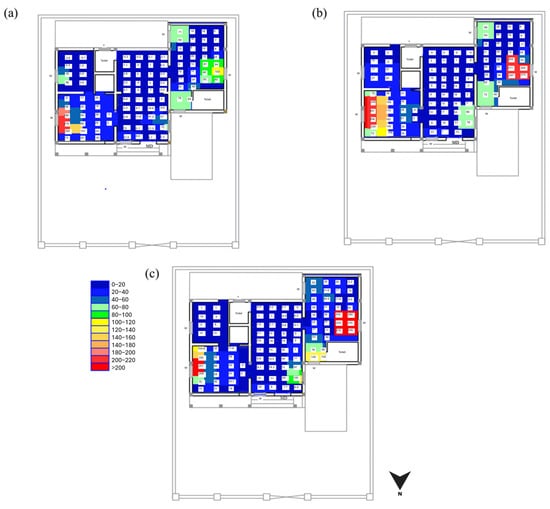

Figure 3 and Table 2 show the illuminance values at 9 a.m., 12 p.m., and 3 p.m., respectively. The identified illuminance levels indicate insufficient daylighting in all spaces compared to the NBCI standards. Except for the points next to the window at all three times, the other points have inadequate daylight. Insufficient daylighting occurs further from the window, although the illuminance value for DR is satisfied near the window. Similarly, the illuminance levels required for the bedroom, DR, and living room are reached near the window. However, they are less than the recommended values on average, resulting in inadequate daylight in other areas.

Figure 3.

Illuminance value calculated with room index points: (a) at 9 a.m., (b) at 12 p.m., and (c) at 3 p.m.

Table 2.

DF values for the rooms at 9 am, 12 pm, and 3 pm.

The building’s orientation affects the amount of daylight that penetrates the space. When the sun is on the eastern side in the morning (at 9 am), the eastern rooms receive more daylight than the western ones. Conversely, in the late afternoon (at 3 pm), western rooms experience higher levels of illuminance. In spaces like the LR, the rear end receives the least daylight at noon and 3 pm due to limited penetration and distance from the window. Although rooms 1 and 2, along with the LR, have windows on the outer wall, the illuminance remains low because the roof blocks daylight from entering. The kitchen and LR appear to be the least lit spaces due to low WWR and external obstructions, such as the roof and neighboring buildings. The WWR is low across all spaces and should be increased during redesign to maximize daylight access. Thus, these values provide a more detailed and realistic understanding of daylighting at selected points and times. The data from the illuminance meter study can help improve daylighting provisions. Additionally, the results showed that the measured illuminance in each room falls below National Building Code standards. While the illuminance meter offers valuable information, a more comprehensive assessment involves analyzing daylighting performance throughout the year using simulation methods. Thus, the data indicate that indoor illuminance values vary significantly throughout the day due to the dynamic nature of sunlight and its interaction with the building’s architectural features, such as window size, orientation, and the presence of external obstructions. As a next step to enhance daylighting, a skylight was added to the model, and modifications to WWR and orientation were explored through iterative simulations to examine the impact of architectural design parameters on daylighting performance in the residence.

2.2.2. Simulation Method Using DesignBuilder

One well-known research method that provides reliable predictions but requires considering various factors is daylight simulation. Simulations are among the most effective methods for precise forecasting. Despite the availability of advanced devices, simulations still demand significant computational power and time, especially for iterative design decisions [51]. Radiance, a simulation engine, accurately predicts internal illuminance under overcast sky conditions [52]. Using yearly climate-based daylight regulations from simulations, subjective lighting assessments can determine whether a space appears dark or luminous and identify instances where overall daylight levels are insufficient [53]. Research indicates that maximizing indirect corneal illuminance depends on the reflective properties of room surfaces [54]. Such properties are incorporated, and the simulation is conducted in the later stages.

The study examines the impact of WWR, orientation, and SRR on the selected residential house. Along with modifying the WWR and orientation and using DesignBuilder simulation software, a skylight was added to the existing home typology to maximize daylighting output. Table 3 shows the properties of the simulated model. Weather data for Chennai, India, from the World Meteorological Organization recorded for 2009–2023 via the Climate One Building database (www.climate.onebuilding.org, accessed on 30 November 2025) [55], showed mostly overcast sky conditions. For analysis, heat-absorbing glass was used as the glazing type, with a VLT of 0.45, a U-value of 1.5, and a SHGC of 0.25. This combination helps reduce solar heat gain while allowing moderate daylight transmission in the region’s cloudy weather.

Table 3.

Simulation attributes of the residential building.

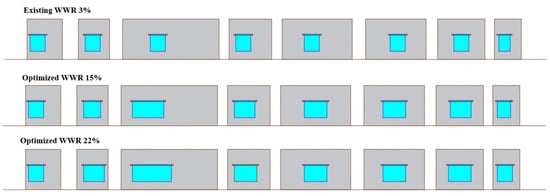

Figure 4 illustrates the iterations and model used for the simulation. The warm-humid climate was thoroughly integrated into the study design. The simulation utilized an EnergyPlus weather file for Chennai, India (2009–2023), which accurately reflects the region’s typical solar radiation, cloud cover, and humidity patterns. In this study, a VLT of 0.45 was used, based on the most common glazing type in residential buildings in Chennai’s warm-humid region, as determined by market surveys and availability. This value aims to represent the current construction practices and occupant preferences for privacy, thermal comfort, and glare control.

Figure 4.

Existing and optimized WWR for iteration.

The VLT was kept constant to limit the scope of variables and focus specifically on evaluating the combined effect of architectural design parameters such as WWR, SRR, and orientation. While glazing enhancements such as increasing the VLT or applying thin films are valid retrofit strategies after construction, this study intentionally maintained the VLT at 0.45 to isolate the combined effects of architectural design variables—WWR, SRR, and orientation—on daylighting performance. Based on field data and simulations, the existing WWR of approximately 3% was found to be insufficient for adequate daylight penetration in both methods. Therefore, the study tested increased WWRs of 15% and 22% through simulation, rather than relying on a single uniform value, and the existing case itself presents different WWR percentages across orientations. Building on these baseline conditions, the proposed scenarios introduce multiple façade-specific ratios to enhance daylight performance. In addition, orientation-specific shading devices have been incorporated—particularly on the south façade—to ensure realistic control of solar ingress and to reflect practical design strategies for warm tropical climates. These values align with recommended thermal comfort and visual quality ranges for warm, humid climates, supported by studies [18,19,20] showing that a 15–30% WWR effectively balances daylight and heat gain, especially when combined with reflective glazing or skylights. Raising VLT without accounting for orientation or shading can increase glare and solar heat gain, reducing overall comfort. Therefore, although advanced glazing systems are promising, this study emphasizes architectural parameters that provide essential passive design guidance for residential buildings. Future research might examine how glazing types and retrofit options, such as reflective films or new technologies, affect performance. Moreover, the sun’s east-to-west path across the southern hemisphere greatly influences indoor light levels and daylight patterns. Previous research has highlighted the importance of atrium shape and orientation in relation to sunlight, particularly in atrium buildings [60]. It is crucial to ensure proper shading for building windows, as inadequate shading can increase cooling demands and glare, particularly in hot climates [61]. Thus, the performance of windows has been analyzed with a focus on VLT, window type, and orientation to maximize thermal and visual comfort [62]. However, research in warm, humid climates remains limited. Therefore, optimizing the structure’s efficiency involved considering WWR modifications ranging from 15% to 22%. The middle option achieves a better balance by skillfully managing the trade-off between daylight access and glare reduction. Raising the WWR to 40% or 50% is likely to increase cooling energy use and cause glare-related discomfort [16]. A detailed analysis of four orientations, a range of SRRs, and WWR variations was conducted to assess different daylight metrics.

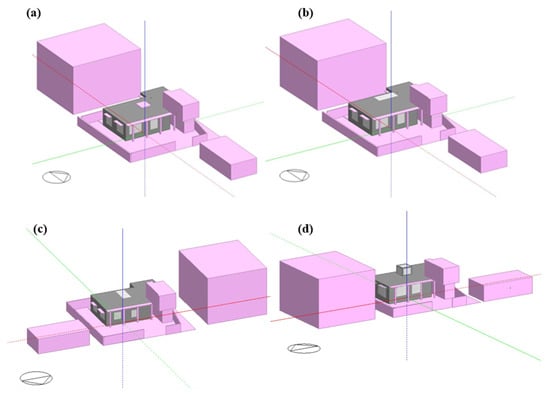

Additionally, to maintain visual comfort and promote realistic architectural design, external horizontal shading devices were incorporated for all window configurations. As WWR increased, the shading depth proportionally increased, based on a projection factor of 0.5 times the window height, in accordance with standard passive design practices for warm-humid climates [39]. This approach ensures that the benefits of increased daylight from glazing are balanced by solar control measures that reduce glare and overheating. Although only fixed shading was modeled, future studies will explore variable shading systems and advanced control strategies. Figure 5 shows the DesignBuilder model of the selected residence. Table 4 lists the various variables simulated under the assumptions of a 0.8 m work plane height, a 50% internal reflectance wall, a 70% ceiling, a 20% floor, and a 20% furniture component.

Figure 5.

DesignBuilder model of the residence: (a) SRR 1:1, (b) SRR 1:1.5, (c) SRR 1:2, and (d) SRR double-high.

Table 4.

Different variables were iterated for the simulation.

Considering all these, the four SRR values used (4%, 5%, 8%, and a double-height configuration with 4%), along with the above-mentioned WWR and orientation that were selected based on literature recommendations for atrium and skylight sizing in warm-humid climates, as well as practical constraints in residential building design. The double-height atrium variation, with a higher roof height, was included to simulate a vertical skylight well, a common feature of low-rise tropical residences, and to evaluate its potential to improve light penetration depth. The base building remains single-story, and this is a conceptual daylighting simulation for comparative analysis only. This has greatly assisted in providing a comprehensive analysis of the building’s daylight performance.

Table S1 analyzes the sDA’s performance in terms of SRR, WWR, and orientation. WWR and SRR meet the required sDA value of 50% of annual daylight hours at 300 lux [12]. Increased WWR values are associated with higher sDA percentages (15–22%). This suggests that increasing WWR allows more daylight to penetrate the structure, enhancing sDA. The building’s orientation influences sDA values. Structures with windows facing east or north are better positioned to maximize daylight autonomy while reducing glare. Due to openings, the south tends to perform better in terms of sDA percentage, though it also leads to higher glare from solar gain. External barriers surrounding the structures also impact this. According to LEED, glare occurs at illuminance levels above 1000 lux [18]. Windows with proper reflectance levels and shading devices are crucial for mitigating glare. sDA is affected by the size of shading devices, interior reflectance, and VLT. Therefore, this analysis shows that building orientation, WWR, and SRR all influence a building’s sDA performance.

Table S2 displays the UDI performance across different SRRs for various orientations and WWR. The WWRs and SRR have been identified as significant factors influencing UDI, such as sDA, as indicated by the recent study [61]. The UDI metric in this study was calculated as the percentage of floor area with illuminance levels within the range of 300–3000 lux for at least 90% of the occupied hours per year. This study focuses specifically on UDI-a, which represents the UDI range relevant for typical indoor visual tasks. The other UDI components—UDI-f (underlit), UDI-s (supplementary), and UDI-e (excessive)—were not considered, as the intent was to evaluate the portion of daylight that directly contributes to visual comfort and task performance. By focusing on UDI-a, the analysis highlights illuminance levels genuinely beneficial to occupants, while complementary metrics, such as sDA and ASE, capture daylight sufficiency and potential overexposure.

Higher WWR values, such as 15% and 22%, are generally associated with increased UDI percentages, ensuring a balanced daylight range for most of the year. This shows that maximizing UDI benefits can be achieved by increasing the WWR. Such an approach allows a more balanced amount of daylight to enter the space without causing excessive glare or insufficient light. The UDI values are affected by the building’s orientation. Compared with west- and south-facing orientations, east- and north-facing orientations consistently deliver higher UDI. The inference is that building facades facing east or north are strategically beneficial for achieving optimal UDI, as they provide adequate daylight without the risk of under- or over-illumination. The surrounding context, including obstructions and reflective surfaces, can further enhance or mitigate these effects. As highlighted by the LEED Code, uncontrolled daylight, especially above 1000 lux, can cause discomfort glare. Since east- and north-facing orientations are less exposed to direct sunlight, they are more likely to maintain balanced illuminance levels (UDI) and experience fewer instances of extreme brightness. Conversely, west- and south-facing orientations, which are more exposed to direct solar rays, tend to have lower UDI percentages due to frequent over-illuminated conditions, thereby increasing the ASE percentage while decreasing the UDI.

Mitigation strategies, such as installing efficient shading devices, optimal WWR and selecting glazing with suitable properties, are essential for controlling glare and optimizing UDI [63,64]. The depth and configuration of shading devices, along with the reflectance of interior finishes, also influence daylight distribution, thereby affecting UDI. Table 5 shows the ASE readings for the residence. When evaluating how WWR, orientation, and SRR influence ASE, values below 90% suggest a potential glare risk. However, ASE is not a direct glare metric; it is used here as an indicator for zones exceeding 1000 lux for more than 250 h annually per LEED v4.1, with future research planned to include actual glare metrics like DGP. A 15% WWR generally keeps ASE above 90% across most orientations and SRRs, but increasing WWR to 22% causes ASE to drop below 90% in most cases (except 1:2) and orientations—particularly east, north, and south—where ASE decreases to 79.5%, 82.86%, and 84.7%, respectively, indicating increased glare risk. The 1:2 SRR helps maintain ASE above 90%, implying better glare control, and orientation-driven solar exposure explains why east- and west-facing buildings experience higher exposure, while north- and south-facing buildings can still encounter glare without careful WWR–SRR planning.

Table 5.

ASE performance across different SRR for different orientations and WWR.

The results underline the difficulty of achieving a balance between daylight availability and glare control, particularly as WWR increases. While a 15% WWR appears to manage glare across various orientations and SRR, increasing the WWR to 22% enhances daylight penetration. However, it requires more careful planning of other design elements, such as SRR, to prevent excessive glare, particularly in east, north, and south-facing orientations for the chosen cases. Beyond numerical gains in UDI, sDA, and ASE, the findings translate into clear design advantages. The 1:2 SRR provides deeper, well-diffused daylight while maintaining a modest skylight size, reducing the need for larger east–west openings that often cause low-angle glare in warm-humid climates. A 22% WWR enhances lateral daylighting without significantly increasing heat gain. These factors together create brighter circulation areas, minimize dark rear corners, and enable smoother luminance transitions, leading to a more visually comfortable and functional interior environment.

3. Results

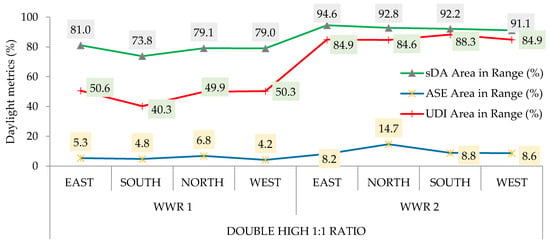

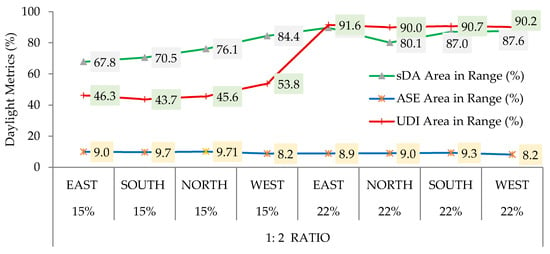

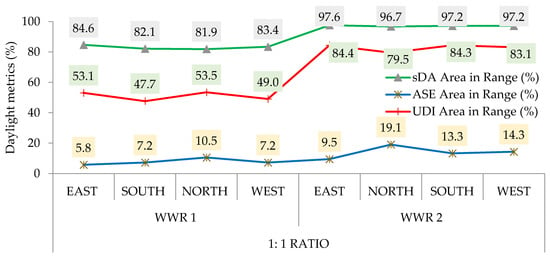

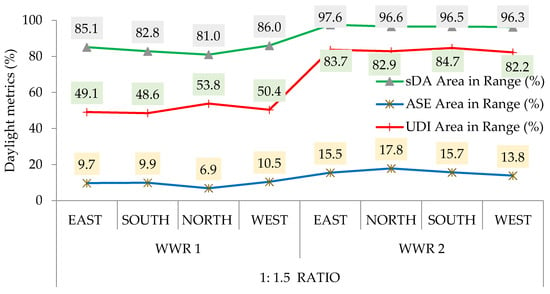

Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present an analysis of the orientation and WWR for each of the four SRR variations. In this regard, the results of daylight metrics, including sDA, ASE (glare), and UDI, were evaluated. The WWR shows that, across all graphs, the house’s daylighting effectiveness improved by 22%. ASE, which is inversely related to glare values, increases as WWR rises, with a few exceptions where this is due to factors such as window size, quantity, or other exterior impediments, such as neighboring buildings. Orientation, the SRR, the WWR, and other factors influence the house’s UDI performance.

Figure 6.

UDI, ASE, and sDA areas in range for the different SRR, orientation, and WWR (double-high 1:1 ratio).

Figure 7.

UDI, ASE, and sDA areas in range for the different SRR, orientation, and WWR (1:2 ratio).

Figure 8.

UDI, ASE, and sDA areas in range for the different SRR, orientation, and WWR (1:1 ratio).

Figure 9.

UDI, ASE, and sDA areas in range for the different SRR, orientation, and WWR (1:1.5 ratio).

As measured by the UDI metric, daylight penetration was calculated by the combined effect of all three. sDA and UDI are performance-related; however, sDA is calculated based on 250 working hours, whereas UDI is a more precise metric. Based on an examination of data on ASE, sDA, and UDI, it can be concluded that the 1:2 SRR effectively manages the trade-off between glare control and daylight quality, surpassing alternative ratios and establishing itself as the preferred choice in many situations.

Correlation Analysis

One of the key variables distinguishing the 1:2 ratio is its ability to preserve a more favorable equilibrium between high sDA and UDI values and comparatively low ASE values across various WWR and orientations. This ratio effectively increases daylight penetration (as indicated by higher sDA and UDI) while maintaining acceptable levels of excessive glare (ASE) compared with the 1:1 and 1:1.5 ratios.

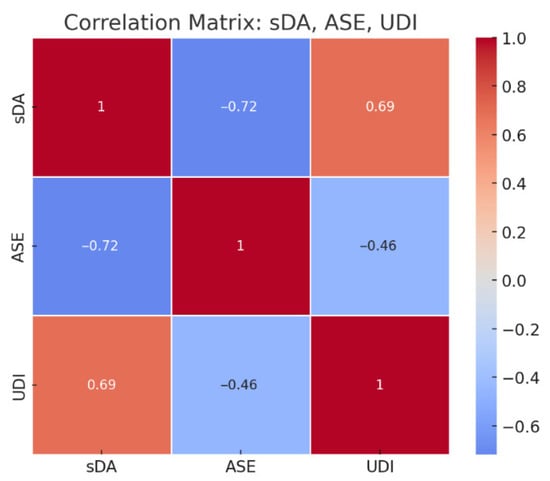

Figure 10 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients for the different metrics. The ASE (1 − ASE) and sDA (−0.719): sDA and ASE (1 − ASE) have a strong negative correlation. As sDA (the percentage of space receiving adequate daylight) increases, ASE decreases. A positive relationship in building design involves striking a balance between adequate daylight and avoiding glare for better performance. sDA and UDI (r = 0.685): sDA and UDI exhibit a moderately strong positive correlation. This indicates that as sDA increases, UDI tends to increase as well. UDI measures the percentage of time when daylight levels are neither inadequate for basic activities nor too high to cause discomfort or require artificial light control. A positive correlation with sDA implies that spaces with good daylight autonomy and UDI spend a significant amount of time with comfortable daylight levels; however, the total hours are higher in UDI than in sDA, indicating a moderate relationship.

Figure 10.

Correlation matrix of key daylight matrix (SDA, UDI, and ASE).

ASE (1 − ASE) and UDI (−0.456): ASE (1 − ASE) and UDI exhibit a moderately negative correlation. This implies that as ASE increases (due to greater exposure to excessive sunlight), UDI decreases (as less time is spent at comfortable daylight levels). This relationship suggests that excessive daylight can cause discomfort and necessitate controlling artificial light, thereby limiting the usefulness of daylight in an area. Thus, these correlations indicate that well-designed spaces can achieve a balance between adequate daylight (high sDA) and reduced exposure to excessive sunlight, resulting in more time spent at comfortable daylight levels (high UDI). This balance is crucial in creating environments that conserve energy, promote occupant comfort, and enhance well-being. The regression model’s values for each dependent variable, with WWR, SRR, and orientation as independent variables, were determined. The correlation trends guided the assignment of weights, prioritizing UDI due to its positive synergy with sDA and inverse relationship with ASE, while ensuring that glare [ASE − (1 − ASE)] was penalized appropriately. Thus, the matrix provides statistical validation for both visual interpretation and multi-metric performance evaluation through the objective function.

4. Discussion

Among the different SRRs analyzed, the 1:2 ratio demonstrates the most balanced daylighting performance across all three metrics—sDA, UDI, and ASE. As shown in the top-right graph, both sDA (R2 = 0.72) and UDI (R2 = 0.80) exhibit consistent growth trends, indicating that the 1:2 ratio effectively enhances daylight autonomy and maintains a substantial portion of the space within the useful daylight range. Notably, the ASE trend (R2 = 0.64) remains relatively stable, meaning that excessive sunlight and glare risks do not increase significantly, making this ratio ideal for warm-humid climates where glare control is critical.

In comparison, the double-high 1:1 ratio produces the highest UDI improvement (R2 = 0.97), but its form may not always be practical for residential typologies, and its sDA increases are slightly lower. The 1:1 ratio, while offering strong daylighting performance, shows a higher ASE trend (R2 = 0.95), suggesting greater potential for glare issues. The 1:1.5 ratio presents moderate improvements across all metrics but does not outperform the 1:2 ratio in balancing daylight enhancement with glare control.

The graphical trends helped inform the development of a multi-metric objective function, used to identify the most balanced configuration across all performance indicators. The final objective function (OF) was structured in Equation (1).

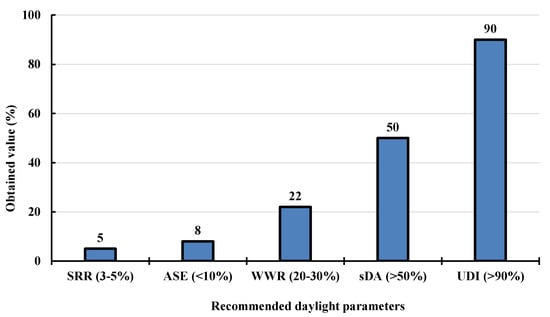

OF = 0.3 (1 − ASE) + 0.3 sDA + 0.4 UDI

This OF assigns the highest weight to UDI (40%), recognizing its comprehensive nature as a comfort-based metric that avoids both under- and over-lighting. The weights used in the objective function were selected based on the correlation patterns among the daylight metrics, with UDI showing the strongest overall relationship with both sDA and ASE and therefore receiving the highest weight. sDA and the glare-free component (1 − ASE) were assigned equal weights to balance daylight adequacy and glare control. To ensure the weighting was not arbitrary, alternative combinations—including equal weights and glare-focused weights—were tested, and all yielded the same optimal configuration, confirming the robustness of the results. Figure 11 indicates a well-balanced design that provides sufficient daylight, minimizes glare risk, and ensures visual comfort, supporting an effective and energy-efficient indoor environment for the selected low-rise residential buildings with the actual surrounding landscapes. The daylight performance aligns well with recommended benchmarks: SRR, ASE, WWR, sDA, and UDI all meet their target ranges.

Figure 11.

The optimal configuration of the selected low-rise case study building at a skylight-to-roof-to-plan ratio of 1:2 and east-north orientation.

Table 6 compares the significant findings with earlier studies. Based on the objective scoring, the SRR 1:2 configuration (5%) combined with a WWR of 22% and an east or north orientation delivered the best overall performance, offering high UDI, adequate sDA, and ASE below the 10% LEED v4.1 threshold. Although other SRRs (e.g., 1:1, 1:1.5) performed well in specific metrics such as sDA, they resulted in higher ASE in certain orientations due to increased exposure to low-angle morning and evening sunlight from east–west window placements, highlighting the combined effects of window direction and building orientation on glare [65,66].

Table 6.

Comparison of the findings with previous studies.

Although other SRRs (e.g., 1:1, 1:1.5) performed well in specific metrics such as sDA, they resulted in higher ASE in certain orientations due to increased exposure to low-angle morning and evening sunlight from east–west window placements, highlighting the com-bined effects of window direction and building orientation on glare [70,71]. SRR and WWR mainly influence light distribution—with SRR creating a broader, more uniform impact, and WWR having a more substantial effect near openings—while orientation affects the quality and seasonal variation in daylight. Orientation offers strategic opportunities to enhance daylight, but site constraints often limit its application, making WWR and SRR vital for managing illuminance levels. These observations are based on daylighting behavior specific to this case-study residential building and should be understood within its spatial layout, glazing type, and surrounding obstructions related to the site. Additionally, daylighting performance is affected by reflectance and shading conditions, including nearby building obstructions. This integrated approach supports evidence-based passive design for warm-humid, low-rise residences [72], highlighting how daylight distribution influences façade proportions, shading strategies, and spatial planning. Improved UDI and sDA values promote uniform lighting, reduce dependence on artificial lighting, and enhance visual comfort and spatial clarity in tropical residential architecture. The residential daylight score (RDS) helps assess daylight autonomy and direct sunlight on a seasonal and daily basis [73].

4.1. Limitations of the Study

While this study offers valuable insights into daylight optimization for single-story residential buildings in warm-humid climates, it has certain limitations. The study focuses on a single building case with fixed parameters—uniform glazing (VLT = 0.45) and static shading—which limits its applicability to diverse real-world conditions. The limitations of the study are as follows:

- The study focuses solely on warm-humid climates, which limits how applicable their findings are. The best daylighting setups identified may not work in buildings located in temperate, cold, or hot-arid areas, where solar angles, cloud cover, and seasonal changes vary widely.

- Since this investigation focuses on a single case-study residence with its unique orientation constraints, urban obstructions, and window layout, the optimal configuration identified reflects the daylighting behavior of this specific building type. However, the core design principles can be adapted and applied to similar low-rise residential settings with comparable spatial and climatic conditions.

- Although climate-based daylight modeling was employed, the simulations depend on simplified assumptions that might not fully capture real-world conditions, such as furniture placement, shading adjustments, occupant details, or environmental shifts.

- The study assesses daylight quality using UDI, sDA, and ASE. Still, it does not consider other important factors, such as glare risk, thermal loads, or the interaction between daylighting and artificial lighting controls. As a result, the overall impact on energy use and visual comfort may be underestimated.

- Following LEED v4.1, this study assesses daylight performance using UDI, sDA, and ASE. However, metrics explicitly developed for residential settings—such as the RDS—are increasingly recommended for evaluating daylight sufficiency in dwellings, as they offer a more residential-specific perspective.

- Only one glazing transmittance value (VLT = 0.45) and a few skylight configurations were tested. Other glazing types, shading systems, or advanced daylighting devices (e.g., light shelves, diffusing skylights, dynamic glazing) were not examined, which limits the range of potential optimized solutions.

Broader geographic analysis would improve generalizability. ASE was used as a glare proxy, although more advanced metrics like DGP would better represent occupant discomfort. Occupant-centered measures, such as vertical or eye-level illuminance, should also be considered in future residential studies.

4.2. Recommendations

This section consolidates the quantitative findings into evidence-based design guidelines for low-rise residential buildings in warm-humid climates. The following recommendations focus on balancing key daylighting metrics—UDI, sDA, and ASE—to promote energy efficiency, visual comfort, health and well-being, and compliance with standards like LEED v4.1. The main goal is to help designers and policymakers design residences based on architectural design parameters and performance.

- Implement an SRR of 1:2 (equivalent to a 5% SRR) combined with a WWR of 22%. This setup offers the best balance of high UDI, adequate sDA, and low ASE, aligning with LEED v4.1 standards.

- Prioritize east-facing configurations with most windows on the north and south facades and few west-facing openings. When combined with appropriate shading and consideration of context, reflectance, and interior layout, this approach improves daylight performance while managing glare and heat gain.

- Use glazing with about 22% WWR and a VLT of 0.45 for low-rise buildings in warm and humid regions.

- Add effective shading devices to block direct sunlight and keep ASE at or below 10% to prevent visual discomfort.

- Prioritize placing most windows on the north and south facades to lower direct solar exposure and reduce low-angle glare.

- Reduce the size and number of windows on east and west facades, as these orientations allow low-angle morning and evening sun to increase ASE.

- If a south-facing orientation is needed, consider lowering the WWR to 15% along with the 5% SRR to maintain good daylighting while controlling glare. If using the 22% WWR for south, add strong glare-control measures such as advanced shading or selective glazing.

- Design to promote a positive relationship between sDA and UDI, ensuring that increased daylight autonomy comes with sufficient usable light.

- Manage the negative relationship between ASE and UDI actively to prevent too much sunlight from reducing effective daylighting.

- Use WWR and SRR as main controls for light intensity, focusing on how light is distributed and concentrated near windows.

- Shape the light environment through building orientation to maximize seasonal and diurnal light benefits.

- Implement an integrated design process that combines scatter plot trends (for visual analysis) and an objective function (for quantitative assessment) to support passive design decisions.

- While the optimal 22% WWR and 1:2 SRR configuration performed best for the studied residence, similar outcomes may differ in buildings with different layouts, obstruction patterns, or climate conditions. Therefore, refining façade proportions, shading details, and spatial layouts based on daylighting results to ensure consistent indoor lighting and reduce the need for artificial lighting can improve the clarity of tropical residential spaces.

Using assessments like DGP to improve occupant comfort analysis, along with vertical or eye-level illuminance measurements, can provide better insights into occupant experience. Showing the importance of tracking year-round occupant comfort and well-being strengthens the argument for adding these metrics to national building codes. At the same time, the workflow offered here gives a repeatable process that can guide the design of similar buildings, helping architects and policymakers develop human-centered, performance-driven daylighting strategies.

5. Conclusions

The research assessed how the WWR, orientation, and SRR affect the daylighting efficiency of a standard one-story residential structure situated in warm-humid climates. Fundamental performance indicators (SDA, ASE, and UDI) were used to assess daylighting efficiency in accordance with LEED v4.1 criteria. The principal discoveries are delineated as follows:

- An SRR of 5% with a plan ratio of 1:2 met standards across all three daylight metrics (UDI, sDA, ASE), while other ratios performed well in sDA but exhibited glare issues based on scatter plot analysis.

- North-facing orientation with the same setup (22% WWR and 5% SRR) also performed well, providing high daylight autonomy with minimal glare, since windows face east and west, ideally for consistent, year-round indirect lighting with little discomfort.

- South-facing orientation showed promising results, especially with 15% WWR and 5% SRR, maintaining strong daylighting levels. However, glare mitigation strategies such as shading devices or selective glazing are recommended if choosing a 22% WWR in this orientation. Most windows on the north and south faces are preferred over those on the east and west to reduce glare, which is why east-facing windows are often paired with those on the north and south.

- Optimal window designs feature glazing with a 22% WWR and a VLT of 0.45, combined with effective shading devices to block glare and achieve an ASE of no more than 10%. While ASE does not directly measure glare perception, it is used here to assess potential visual discomfort from excessive illuminance.

- The east-facing orientation demonstrated the strongest performance, providing ample daylight with minimal glare, especially when most windows were on the south and north facades and fewer on the west.

- UDI was the primary metric for evaluating year-round daylight conditions, while ASE and sDA offered additional assessments aligned with LEED v4.1 standards.

- A positive correlation between sDA and UDI further suggests that higher daylight autonomy leads to better usable daylight levels, while the negative correlation between ASE and UDI highlights that too much sunlight can decrease effective daylight utilization.

Future work could expand and confirm the RDS across a wider variety of climates, building types, and occupant needs to establish universally relevant benchmarks for residential daylight performance. More research should investigate dynamic façades, adjustable glazing systems, and user-adaptive controls. Increasing vertical housing, adopting higher-density forms, and integrating daylight-energy co-simulation with life-cycle assessment can improve scalability. Despite these limitations, the study offers LEED-aligned design insights and confirms the importance of daylighting strategies in low-rise tropical housing. Additional research is necessary to adapt these strategies to multi-story urban settings and promote sustainable, occupant-focused design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/architecture5040125/s1, Table S1: sDA performance across different SRR for different orientations and WWR; Table S2: UDI performance across different SRR for different orientations and WWR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and R.S.P.; formal analysis, K.K., S.G., R.S.P. and R.S.; methodology, K.K., S.G., R.S.P., C.S. and R.S.; data visualization, K.K., C.S. and R.S.; investigation, K.K., S.G., R.S.P., C.S. and R.S.; original draft writing, K.K. and S.G.; data curation, S.G.; data validation, R.S.P. and R.S.; review and editing, R.S.P., C.S. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, for providing research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASE | Annual sunlight exposure |

| DF | Daylight factor |

| DGP | Daylight glare probability |

| DR | Dining room |

| OF | Objective function |

| LEED | Leadership in energy and environmental design |

| LR | Living room |

| NBCI | National Building Code of India |

| sDA | Spatial daylight autonomy |

| SHGC | Solar heat gain coefficient |

| SRR | Skylight-to-roof ratio |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient |

| UDI | Useful daylight illuminance |

| VLT | Visible light transmittance |

| WWR | Window-to-wall ratio |

References

- Rastegari, E.; Adamsson, M.; Aries, M. Daylight potential of Swedish residential environments: Visual and beyond-vision effects and the relationship with well-being assessment. Light. Res. Technol. 2024, 57, 156–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, Ö.K.; Chamilothori, K.; Van Duijnhoven, J.; Aarts, M.P.J.; De Kort, Y.A.W. Restorative Effects of Daylight in Indoor Environments—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Su, Y. Daylight Availability Assessment and Its Potential Energy Saving Estimation—A Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Husin, S.N.F.; Hanur Harith, Z.Y. The Performance of Daylight through Various Windows for Residential Buildings. Asian J. Environ. Behav. Stud. 2018, 3, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenberg Vaz, N.; Inanici, M. Syncing with the Sky: Daylight-Driven Circadian Lighting Design. LEUKOS 2020, 17, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, U.K.; Senthil, R. Influence of balcony greenery on indoor temperature reduction in tropical urban residential buildings. Energy Build. 2025, 343, 115915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, M.; Vlachokostas, A.; Madamopoulos, N. Experimental Demonstration and Performance Evaluation of a Complex Fenestration System for Daylighting and Thermal Harvesting. Sol. Energy 2020, 197, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.; Steemers, K. Daylight Design of Buildings; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.M.R.; Nessim, A.; Fathy, F. Daylighting and Energy Consumption in Museums and Bridging the Gap by Multi-Objective Optimization. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, F.S.; Sa’di, B.; Safa-Gamal, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alrifaey, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S. Energy Efficiency in Sustainable Buildings: A Systematic Review with Taxonomy, Challenges, Motivations, Methodological Aspects, Recommendations, and Pathways for Future Research. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 45, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzarooni, M.; Olabi, A.G.; Mahmoud, M.; Alzubaidi, S.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Study on Improving the Energy Efficiency of a Building: Utilization of Daylight through Solar Film Sheets. Energies 2023, 16, 7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fela, R.F.; Utami, S.S.; Mangkuto, R.A.; Suroso, D.J. The Effects of Orientation, Window Size, and Lighting Control to Climate-Based Daylight Performance and Lighting Energy Demand on Buildings in Tropical Area. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation Conference, Loughborough, UK, 21–22 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahi, N.; Shokri, E. Daylight Illuminance in Urban Environments for Visual Comfort and Energy Performance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; Peng, C. An Investigation of Optimal Window-to-Wall Ratio Based on Changes in Building Orientations for Traditional Dwellings. Sol. Energy 2020, 195, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoul, S.K.; Rijabo, H.G.; Mashena, M.E. Energy Consumption in Buildings: A Correlation for the Influence of Window to Wall Ratio and Window Orientation in Tripoli, Libya. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, O.S. A Comparison between the Daylighting and Energy Performance of Courtyard and Atrium Buildings Considering the Hot Climate of Saudi Arabia. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.L. Daylighting; Routledge eBooks: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tamimi, N.; Qahtan, A. Influence of Glazing Types on the Indoor Thermal Performance of Tropical High-Rise Residential Buildings. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 692, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Ismail, M.; Abdul Rahman, A.M. Energy Efficient Skylight Design in Tropical Houses. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 632, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talip, M.S.; Shaari, M.F.; Ahmad, S.S.; Sanchez, R.B. Optimising Daylighting Performance in Tropical Courtyard and Atrium Buildings for Occupants’ Wellbeing. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2021, 6, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Berardi, U.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Li, D.H.W. Is Atrium an Ideal Form for Daylight in Buildings? Architect. Sci. Rev. 2019, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapisa, R.; Karudin, A.; Martias, M.; Krismadinata, K.; Ambiyar, A.; Romani, Z.; Salagnac, P. Effect of Skylight–Roof Ratio on Warehouse Building Energy Balance and Thermal–Visual Comfort in Hot-Humid Climate Area. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 21, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Dehghan, N. Optimization of Energy Consumption and Daylight Performance in Residential Building Regarding Windows Design in Hot and Dry Climate of Isfahan. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2020, 27, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.G.; Yamín Garretón, J.A.; Pattini, A.E. An Epidemiological Approach to Daylight Discomfort Glare. Build. Environ. 2017, 113, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onubogu, N.O.; Chong, K.K.; Tan, M.H. Review of Active and Passive Daylighting Technologies for Sustainable Building. Int. J. Photoenergy 2021, 26, e8802691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksmiyanti, D.P.E.; Salisnanda, R.P. Atrium Form and Thermal Performance of Middle-Rise Wide Span Building in Tropics. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 462, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freewan, A.A.Y.; Al Dalala, J.A. Assessment of Daylight Performance of Advanced Daylighting Strategies in Large University Classrooms: Case Study Classrooms at JUST. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdad, A.A.; Taib, N.; Allahaim, F.S.; Ajlan, A.M. Parametric Optimization Approach to Evaluate Dynamic Shading within Double-Skin Insulated Glazed Units for Multi-Criteria Daylighting Performance in Tropics. J. Daylighting 2024, 11, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Zala, P.; Gupta, S.; Varshney, S. Solar Concentration-Based Indoor Daylighting System to Achieve Net Zero Sustainable Buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.J.; Islam, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Cuce, E. Energy Consumption, Power Generation, and Performance Analysis of Solar Photovoltaic Module-Based Building Roof. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Luo, Z.; Ghahramani, A.; Zhuang, D.; Sun, C. A Study of Subjective Evaluation Factors Regarding Visual Effects of Daylight in Offices Using Machine Learning. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.; Priya, A.V.; Maduru, V.R.; Rahaman, A.; Arıcı, M.; Kontoleon, K.J.; Li, D. Glazing Systems Utilizing Phase Change Materials: Solar-Optical Characteristics, Potential for Energy Conservation, Role in Reducing Carbon Emissions, and Impact on Natural Illumination. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Satvaya, P.; Bhattacharya, S. Effects of Indoor Lighting Conditions on Subjective Preferences of Task Lighting and Room Aesthetics in an Indian Tertiary Educational Institution. Build. Environ. 2023, 249, 111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshalatha; Patil, S.; Kini, P.G.; Sathwik, B. Daylighting Analysis for Selection of Optimal Hospital Building Form in Warm Humid Climate. Energy Build. 2025, 341, 115858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Xie, L.; Zhong, Q. Multi-Objective Optimization of Thermochromic Glazing: Evaluating Useful Daylight Illuminance, Circadian Stimulus, and Energy Performance with Implications for Sleep Quality Improvement. Energy Build. 2025, 333, 115460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavuthimadathil, S.; Ramamurthy, K. Design of a Passive Fibre Optic System with Non-Tracking Imaging CPC Collector and Optimised Fibre Bundle for Indoor Illumination. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 107, 112662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Oswald, A.; Yang, X. Effectiveness of daylighting design and occupant visual satisfaction in a LEED Gold laboratory building. Build. Environ. 2010, 46, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; Jing, R.; Tang, R.; Wang, M. State-of-the-art review of urban building energy modelling on supporting sustainable development goals. Appl. Energy 2025, 402, 126924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Huang, H.; Zhang, W. Towards building floor-level nighttime light exposure assessment using SDGSAT-1 GLI data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 223, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataee, S.; Lopes, M.; Relvas, H. Environmental comfort in urban spaces: A systematic literature review and a system dynamics analysis. Urban Clim. 2025, 60, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, C.; Gong, R.; Jin, E. Elevator Selection Methodology for Existing Residential Buildings Oriented Toward Living Quality Improvement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebir, N.; Miranda, N.D.; Sedki, L.; Hirmer, S.; McCulloch, M. Opportunities stemming from retrofitting low-resource East African dwellings by introducing passive cooling and daylighting measures. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 69, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejon-Esparza, N.M.; González-Trevizo, M.E.; Martínez-Torres, K.E.; Santamouris, M. Optimizing Urban Morphology: Evolutionary Design and Multi-Objective Optimization of Thermal Comfort and Energy Performance-Based City Forms for Microclimate Adaptation. Energy Build. 2025, 342, 115750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Cho, S.; Chow, D.H.C. Urban Morphology Indicators and Solar Radiation Acquisition: 2011–2022 Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenigsberger, O.H.; Ingersoll, T.G.; Mayhew, A.; Szokolay, S.V. Manual of Tropical Housing and Building: Climatic Design; Universities Press: Hyderabad, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Building Code of India 2016. Available online: https://www.bis.gov.in/standards/technical-department/national-building-code/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- DesignBuilder Software Ltd. (2019). Available online: https://designbuilder.co.uk/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- EnergyPlus. Available online: https://energyplus.net/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Sokkar, R.; Alibaba, H.Z. Thermal Comfort Improvement for Atrium Building with Double-Skin Skylight in the Mediterranean Climate. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.; Esquivias, P.; Moreno, D.; Acosta, I.; Navarro, J. Climate-Based Daylighting Analysis for the Effects of Location, Orientation and Obstruction. Light. Res. Technol. 2014, 46, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M. A Review on Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict Daylighting Inside Buildings. Sol. Energy 2020, 202, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharvari, F. An Empirical Validation of Daylighting Tools: Assessing Radiance Parameters and Simulation Settings in Ladybug and Honeybee against Field Measurements. Sol. Energy 2020, 207, 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembilla, E.; Drosou, N.C.; Mardaljevic, J. Assessing Daylight Performance in Use: A Comparison between Long-Term Daylight Measurements and Simulations. Energy Build. 2022, 262, 111989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Cai, W.; Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Xue, P.; Dai, Q. Efficient Circadian Daylighting: A Proposed Equation, Experimental Validation, and the Consequent Importance of Room Surface Reflectance. Energy Build. 2020, 210, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data. Available online: www.climate.onebuilding.org (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Nabil, A.; Mardaljevic, J. Useful Daylight Illuminance: A New Paradigm for Assessing Daylight in Buildings. Light. Res. Technol. 2005, 37, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M. 100 Years of Daylighting: A Chronological Review of Daylight Prediction and Calculation Methods. Sol. Energy 2019, 194, 360–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). LEED Rating System. 2020. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/leed (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Q.; Hu, K. A Study on Daylighting Metrics Related to the Subjective Evaluation of Daylight and Visual Comfort of Students in China. Energy Build. 2023, 287, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wei, R.; Zhao, S. A Case Study on Multi-Objective Optimization Design of College Teaching Building Atrium in Cold Regions Based on Passive Concept. Buildings 2023, 13, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffat, R.M.; Ahmad, R.M. Determination of Optimal Energy-Efficient Integrated Daylighting Systems into Building Windows. Sol. Energy 2020, 209, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhagla, K.; Mansour, A.; Elbassuoni, R. Optimizing Windows for Enhancing Daylighting Performance and Energy Saving. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, M.; Shu, C.; Mmereki, D.; Hossain, M.U.; Zhan, X. Impact Analysis of Window-Wall Ratio on Heating and Cooling Energy Consumption of Residential Buildings in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone in China. J. Eng. 2015, 2015, 538254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denan, Z.; Abdul Majid, N.H. An Assessment on Glare from Daylight through Various Designs of Shading Devices in Hot Humid Climate: Case Study in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2015, 7, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.H.W.; Wong, S.L. Daylighting and Energy Implications Due to Shading Effects from Nearby Buildings. Appl. Energy 2007, 84, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.; Yim, W.S.; Kim, D.D. Evaluation of Daylight and Cooling Performance of Shading Devices in Residential Buildings in South Korea. Energies 2020, 13, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Joarder, M.A.R. Optimising Daylighting and Energy Performance in Deep-Plan Tropical Buildings: Uniform versus Staggered Lightwell Configurations for Multistory Apartments. J Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Ao, Y.; Long, Y.; Martek, I. Thermal Performance of Post-Disaster Housing and Its Impact on Occupant Comfort: An Integrated ML-ABM Approach. Build Environ. 2025, 281, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalabadi, S.T.; Hosseini, M.; Azmoodeh, M. Integration of Bio-Inspired Adaptive Systems for Optimizing Daylight Performance and Glare Control. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpong, E.; Uzuegbunam, F.O.; Ibem, E.O.; Udomiaye, E. Daylighting Performance Evaluation in Tropical Lecture Rooms: A Comparative Analysis of Static and Climate-Based Metrics. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atthaillah; Mangkuto, R.A.; Bintoro, A. Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization of Facade Design to Improve Daylight Performance of Tropical Classrooms with an Adjacent Building. J. Daylighting 2025, 12, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaimathy, K.; Priya, R.S.; Rajagopal, P.; Pradeepa, C.; Senthil, R. Daylight Performance Analysis of a Residential Building in a Tropical Climate. Energy Nexus 2023, 11, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, T.; Park, Y.C. Testing the residential daylight score: Comparing climate-based daylighting metrics for 2444 individual dwelling units in temperate climates. Light. Res. Technol. 2020, 52, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).