Inclusive Mediterranean Torrent Cityscapes? A Case Study of Design for Just Resilience Against Droughts and Floods in Volos, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Can Resilience Be Just and Inclusive?

1.2. Infrastructure and Landscape, Care and Co-Vulnerability

2. Methodology: Inscribing the Mediterranean Torrentscapes of Volos as Crucial Landscapes

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Timescale Analysis I: Mediterranean Torrents Observed During a Vast Timescale

- “Often a vast column of water towers in the sky,

- and clouds from the heights gather into a vile tempest

- of dark rain:

- …the ditches fill, and the channelled rivers swell and roar,

- and the heaving ocean boils in the narrow straits.”

- “<he> brings upon his crops a water course, guiding

- its streamlets as he will, and, when the scorched land

- swelters, and the green blades would feign die, lo, from

- the brow of the hillside channel he decoys the water.

- The water, as it falls, wakes murmurs amid the smooth

- stones, and with its gushing stream gives the thirsty

- fields just the draughts they need”

3.2. Timescale Analysis II: Chronomapping Analysis and the Krafsidonas Torrent’s Turn: Landscape, Floodscape, or Infrastructure?

3.2.1. The Founding of Modern Volos and the Krafsidonas Torrent [1881,1882,1883]

3.2.2. Infrastructure Takes Control of Torrent Krafsidonas (1881–1887), (1888–1910)

3.2.3. The Krafsidonas Torrent as an Industrial Zone (1888–1910)

3.2.4. Catastrophic Floods During the 20th and 21st Centuries

3.2.5. From Top-Down to Community and Bottom-Up Initiatives in the 20th and 21st Centuries

3.3. Vast Spatial Scales: National Legislative Framework Analysis

3.3.1. Water Legislative Framework in Greece: Either Droughts or Floods

3.3.2. Torrent-Related National Legislation: Invisible, Yet Flooding

3.3.3. The Regional Climate Change Adaption Plan

3.4. Integrated Catchment Management Plans: An Approach of Territorial Scale in Relation to EU Guidelines and Directives

3.4.1. Upper Catchments

3.4.2. Intermediate (Mid)-Catchments

3.4.3. Lower Catchments

3.4.4. Overall Catchment Assessment Summary

3.4.5. Ecotones as Non-Anthropocentric Eco-Corridors, Transversal to Each Catchment

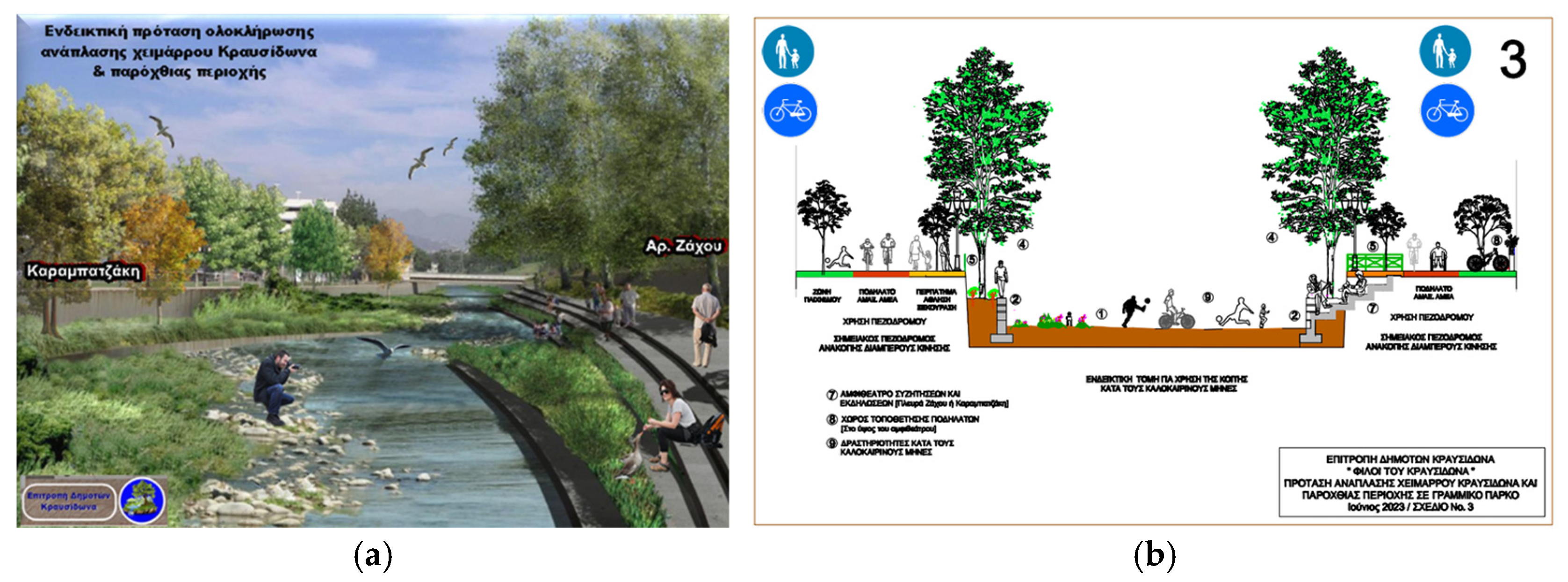

3.5. Research for Torrentscape Restoration Through Landscape Design([RtD) for Krafsidonas’ Lower Catchment Scale

3.6. Synchronic Actions for Volos’ Torrentscapes, from an Anthropological Standpoint

3.6.1. Floodmarks Exhibition’s Tracings, on the Krafsidonas Torrentscape

3.6.2. “The Water Remembers”, Geolocated Media Walks

4. Discussion: Understanding the Krafsidonas Torrentscape Under the Prisms of Co-Vulnerability and Just Resilience

4.1. Co-Vulnerability

- “…through such mutual helpfulness men repair

- the ravages of tempest, earthquake, time.”

4.2. Addressing Social Justice for Just Resilience

5. Conclusions

- A visionary analysis and critique of the national, regional, and EU legislative framework and guidelines concerning the management of perennial Mediterranean torrents and streams, is provided. A critical approach to the actual national legislative framework concerning the hydraulic basins—catchments—and their waterbeds, the management of their waters, their flood-risk management plans, as well as the regional framework for the adaptation to climate change is effectuated, exposing serious gaps between the Greek and EU framework, and the lack of a consistent response to the dual challenges of floods and droughts.

- A path to envision and discuss possible parameters of an integrated catchment management plan for the three Volos’ city torrents—Xerias, Krafsidonas, and Anavros—has been opened. An argument for their ecological value as ecotones and eco-corridors, and their diachronic bonds with the riparian communities has been developed. Strengthening this vision is in line with the EU guidelines and directives, but concerning the case study seems almost utopian, considering the severe lacunas observed, concerning the absence of all of these three torrents from the River Basin Management Plans of the region of Thessaly. To investigate ways of staging alternative possibilities and finding the means for the implementation of such an ambitious plan, in direct collaboration with the riparian communities, is envisioned as a stable step towards this direction.

- Transdisciplinary research was conducted, aiming at the combination of architectural, landscape design, and planning qualities, in collaboration with civil engineering and forest engineering, and in synergy with social anthropological methodologies and perspectives, for attaining flood risk mitigation with the objective of just resilience, including visions of the Krafsidonas’ riparian community’s inhabitants.

- The role of oral history, and direct discussions with local communities and bottom-up initiatives, as crucial for the preservation of memories and experiences which enrich our understanding of torrentscapes, emerges from this approach. The narratives concerning the sharing of traumas from flood events, but also memories of joy which exhibit the affectionate bonds between the riparian communities and their torrentscapes, and the collective mapping of the two floods, are complementary ways to increase awareness on the manifold nature of Mediterranean torrentscapes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latour, B. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 1-5095-3059-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aït-Touati, F.; Arènes, A.; Grégoire, A. Terra Forma: Manuel de Cartographies Potentielles; Éditions Les Presses du Réel: Dijon, France, 2019; ISBN 978-2-490-07795-3. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Weibel, P. Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 0-262-04445-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, D. The Climate of History: Four Theses. Crit. Inq. 2009, 35, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T. Ecology without the Present. Oxf. Lit. Rev. 2012, 34, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriendos, M.; Gil-Guirado, S.; Pino, D.; Tuset, J.; Pérez-Morales, A.; Alberola, A.; Costa, J.; Balasch, J.C.; Castelltort, X.; Mazón, J. Climatic and Social Factors behind the Spanish Mediterranean Flood Event Chronologies from Documentary Sources (14th–20th Centuries). Glob. Planet. Change 2019, 182, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G.; Macklin, M.G.; Zielhofer, C.; Jones, A.F.; Machado, M.J. Holocene Flooding and Climate Change in the Mediterranean. Catena 2015, 130, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Engineering Resilience Versus Ecological Resilience; Engineering within Ecological Constraints; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban Resilience for Whom, What, When, Where, and Why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorn, N.; Gardoni, P.; Murphy, C. A Multidisciplinary Definition and Evaluation of Resilience: The Role of Social Justice in Defining Resilience. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2018, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, J.; Novák, L. (Eds.) Chapter 6 Torrent Control. In Developments in Soil Science; Soil Conservation and Silviculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 23, pp. 148–289. [Google Scholar]

- Diprose, K. Resilience Is Futile. Soundings 2015, 58, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank: The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- European Environment Agency. European Climate Risk Assessment Executive Summary—EEA Report 01/2024; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks; Official Journal of the European Union; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sargentis, G.-F.; Iliopoulou, T.; Ioannidis, R.; Kougia, M.; Benekos, I.; Dimitriadis, P.; Koukouvinos, A.; Dimitrakopoulou, D.; Mamassis, N.; Tsouni, A.; et al. Technological Advances in Flood Risk Assessment and Related 1 Operational Practices since the 1970s: A Case Study in the 2 Pikrodafni River of Attica. Water 2025, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprotny, D.; Terefenko, P.; Śledziowski, J. HANZE v2. 1: An Improved Database of Flood Impacts in Europe from 1870 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 5145–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokman, A. On Designing Infrastructure Systems as Landscape. In Topology. Landscript 3; Zürich, E.T.H., Ed.; Jovis Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, R.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; Sargentis, G.-F. Landscape Design in Infrastructure Projects-Is It an Extravagance? A Cost-Benefit Investigation of Practices in Dams. Landsc. Res. 2022, 47, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, R.; Mamassis, N.; Efstratiadis, A.; Koutsoyiannis, D. Reversing Visibility Analysis: Towards an Accelerated a Priori Assessment of Landscape Impacts of Renewable Energy Projects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, H. Thoughts on the Aesthetics of Dams. Int. J. Hydropower Dams 2011, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Tsani, T.; Pelser, T.; Ioannidis, R.; Maier, R.; Chen, R.; Risch, S.; Kullmann, F.; Mckenna, R.; Stolten, D.; Weinand, J. Quantifying the Trade-Offs between Renewable Energy Visibility and System Costs. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, E.; Lingg, S.; Lomoschitz, C. Feminist Nightscapes. FKW//Zeitschrift Für Geschlechterforschung Und Visuelle Kultur 2024, 74, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, B. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2013, 42, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, E.; Lingg, S. Introduction//feminist infrastructural critique. Life-affirming practices against capital. FKW//Zeitschrift Für Geschlechterforschung Und Visuelle Kultur 2024, 74, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.M.; Zettel, T.; Neimanis, A. Feminist Infrastructure for Better Weathering. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2021, 36, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, J. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 1-003-07067-1. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, J.; Keller, P. An Analytical Framework to Examine Empowerment Associated with Participatory Geographic Information Systems (PGIS). Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 2005, 40, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, J.; Everett, G. Sustainable Blue-Green Infrastructure: A Social Practice Approach to Understanding Community Preferences and Stewardship. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulou, D.; Dimitriadis, P.; Ioannidis, R.; Sargentis, G.-F.; Chardavellas, E.; Sigourou, S.; Pagana, V.; Tsouni, A.; Mamassis, N.; Koutsoyiannis, D.; et al. The Importance of Citizens’ Engagement in the Implementation of Civil Works for the Mitigation of Natural Disasters with Focus on Flood Risk. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts; European Geosciences Union: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, R.; Zakynthinou-Xanthi, M.; Mamassis, N.; Moraitis, K. An Initial Investigation of the Potential of Participatory Landscape Assessment through Crowdsourcing within University Education. J. Sustain. Dev. Cult. Tradit. SDCT 2024, 3, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Horden, P.; Purcell, N. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-631-21890-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bombino, G.; Boix-Fayos, C.; Gurnell, A.M.; Tamburino, V.; Zema, D.A.; Zimbone, S.M. Check Dam Influence on Vegetation Species Diversity in Mountain Torrents of the Mediterranean Environment. Ecohydrology 2014, 7, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.2 Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure; UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH): Nottingham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Papailias, P. Floodmarks. Exhibition of the University of Thessaly and Pelion Summer Lab for Cultural Theory and Experi-mental Humanities. 2025. Available online: https://snfphi.columbia.edu/events/floodmarks/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Volk, K. Vergil’s Georgics; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 0-19-156229-7. [Google Scholar]

- Papamargariti, S.; Phokaides, P. Hydrocultures of Thessaly in a Diachronic Perspective” [Special Research Topic]; Department of Architecture, University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, B.; Batziou, A.; Adrymi-Sismani, V.; Mommsen, H.; Maran, J.; Prillwitz, S. Pottery Production, Exchange and Consumption in Late Bronze Age Magnesia (Thessaly): Results of Neutron Activation Analysis of Pottery from Dimini, Volos (Nea Ionia, Kastro/Palaia), Pefkakia and Velestino. Annu. Br. Sch. Athens 2023, 118, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastaoglou, V. Volos: Portrait of the City in the 19th and 20th Century; Publishing House of the University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2002; ISBN 978-960-86742-8-8. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Magnisia sto Perasma tou Xronou. Magnisia in the Passing of Time. Volos Magnisia. 12 July 2013. Available online: https://volosmagnisia.wordpress.com (accessed on 30 March 2025). (In Greek).

- Karagiannidis, A.; Ntafis, S.; Lagouvardos, K. First Comparison of Rainfall from Storms Daniel and Elias. Meteo Articles. 2023. Available online: https://www.meteo.gr/article_view.cfm?entryID=2951 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Dimitrakopoulou, E.; Diamantouli, E.; Petras, A.; Papailias, P.; Vyzoviti, S.; Marou, T.; Themou, M.; Kissas, L.; Ioannidis, R.; Kouzoupi, A. After the Flooding: Living Within a Mediterranean Torrentscape. In Book of Full Text Proceedings, VOL2/IFLA 60th Wold Congress—Code Red for Earth; Şahin, Ş., Çabuk, A., Uslu, A., Kaymaz, I., Bakkaloğlu, A.C., Ok, G., Eds.; International Federation of Landscape Architecture (IFLA): Instanbul, Turkiye, 2025; Available online: https://api.peyzajmimoda.org.tr/uploads/PublicationFiles/2025-03-18-14-26-52-007629.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Myofa, N. Neighbourhood of Social Housing Estates in Tavros. Athens Soc. Atlas 2020, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Trigonis. Nea Ionia of 1933. The Journalist Research of Athos Trigonis, for the Newspaper ‘People’s Voice”, “Life and Needs of the Settlement of Nea Ionia”; Iones [Cultural House of Asia Minor people from Nea Ionia]: New Ionia, Magnesia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- LIFE Programme for the Environment, European Commission. LIFE--Environment in Action: 56 New Success Stories for Europe’s Environment; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2001; ISBN 92-894-0272-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. First Revision of the Flood Risk Management Plan for the River Water Basin of the Water District of Thessaly (EL08)—FRMP; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2024. Available online: https://floods.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/EL08_2round_consultation_P11-T1.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Greek Government. Government Gazette Issue A’ 280/9.12.2003; Water Protection and Management—Harmonization with Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000, Pub. L. No. Law 3199/2003 (FEK A’ 280/9.12.2003, 280 280 4821); Greek Government: Athens, Greece, 2003. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/sites/default/files/2019-07/280a_03.1126767280457.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. Second Revision of the Management Plan of the River Basin for the Water District of Thessaly (EL08)—RBMP; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2024. Available online: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/EL08_2REV_P4.5_Mitrwo-Prost.-Per.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. First Revision of the Management Plan of the River Basin for the Water District of Thessaly (EL08)—RBMP; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2024. Available online: https://wfdver.ypeka.gr/el/management-plans-gr/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. First Revision of the Flood Risk Management Plan for the River Water Basin of the Water District of Thessaly (EL08)—FRMP; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2024. Available online: https://floods.ypeka.gr/sdkp-lap/maps-1round/sdkp-el08-1round/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Region of Thessaly Plan for the Adaptation to Climate Change, approved by the Ministry of Environment and Energy and the Regional Council of Thessaly 2025. Available online: https://www.thessalia.gov.gr/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- European Parliament. Regulation 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- European Commission Critical Infrastructure Protection & Resilience—EC Technical Guidance on Climate Proofing of Infrastructure. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/cipr/items/722278/en (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Green Infrastructure Policy Official Journal of the European Union. European Parliament Resolution of 12 December 2013 on Green Infrastructure—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital (2013/2663(RSP)); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- HVA. HVA First Report Regarding Post-Disaster Remediation. 2023. Available online: https://www.government.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/HVA-Fact-Finding-Mission-Report-on-Thessaly-Post-Disaster-Remediation.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zema, D.A.; Carrà, B.G.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Filianoti, P.G.F.; Pérez-Cutillas, P.; Conesa-García, C. Modelling Water Flow and Soil Erosion in Mediterranean Headwaters (with or without Check Dams) under Land-Use and Climate Change Scenarios Using SWAT. Water 2022, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. ‘Sponge City’: Theory and Practice; [Office Website]; Turenscape: Beijing, China, 2015; Available online: https://www.turenscape.com/topic/en/spongecity/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Haraway, D. When Species Meet; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2008; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Staying with the Trouble for Multispecies Environmental Justice. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2018, 8, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noukakis, Y. Krafsidonas: Contact Zone (Supervised by Giannisi Phoebe and Tzirtzilakis Yorgos); Department of Architecture of the University of Thessaly: Volos, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzimentor, A.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Mazaris, A.D. A Review of Green Infrastructure Research in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R. Research by Design: Proposition for a Methodological Approach. Urban Sci. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, S.; Bobbink, I. Design-Related Research in Landscape Architecture. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, M.T. Cicero de Officiis; William Heinemann: London, UK, 1921; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. The Force of Nonviolence; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.J. Training in the Contact Zone: Power, Play, and Invention in the Sport of Agility; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pelion Summer Lab. “The Water Remembers”. Geolocated Media Walks; Pelion Summer Lab: Volos, Greece, 2024; Available online: https://www.pelionsummerlab.net/tonerothimatai.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Doherty, G. Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Neimanis, A. Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 1-4742-7540-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Notice Technical Guidance on the Climate Proofing of Infrastructure in the Period 2021–2027; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- McKittrick, K.; Woods, C.A. Black Geographies and the Politics of Place; South End Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand, M. Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1-5095-4624-3. [Google Scholar]

- The UN General Assembly. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; A/CONF; UN: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 151, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitrakopoulou, E.; Diamantouli, E.A.; Themou, M.; Petras, A.; Marou, T.; Noukakis, Y.; Vyzoviti, S.; Kissas, L.; Papamargariti, S.; Ioannidis, R.; et al. Inclusive Mediterranean Torrent Cityscapes? A Case Study of Design for Just Resilience Against Droughts and Floods in Volos, Greece. Architecture 2025, 5, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040124

Dimitrakopoulou E, Diamantouli EA, Themou M, Petras A, Marou T, Noukakis Y, Vyzoviti S, Kissas L, Papamargariti S, Ioannidis R, et al. Inclusive Mediterranean Torrent Cityscapes? A Case Study of Design for Just Resilience Against Droughts and Floods in Volos, Greece. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040124

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitrakopoulou, Efthymia, Eliki Athanasia Diamantouli, Monika Themou, Antonios Petras, Thalia Marou, Yorgis Noukakis, Sophia Vyzoviti, Lambros Kissas, Sofia Papamargariti, Romanos Ioannidis, and et al. 2025. "Inclusive Mediterranean Torrent Cityscapes? A Case Study of Design for Just Resilience Against Droughts and Floods in Volos, Greece" Architecture 5, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040124

APA StyleDimitrakopoulou, E., Diamantouli, E. A., Themou, M., Petras, A., Marou, T., Noukakis, Y., Vyzoviti, S., Kissas, L., Papamargariti, S., Ioannidis, R., Papailias, P. c., & Kouzoupi, A. (2025). Inclusive Mediterranean Torrent Cityscapes? A Case Study of Design for Just Resilience Against Droughts and Floods in Volos, Greece. Architecture, 5(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040124