Definition of Emerging Microplastic Syndrome Based on Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

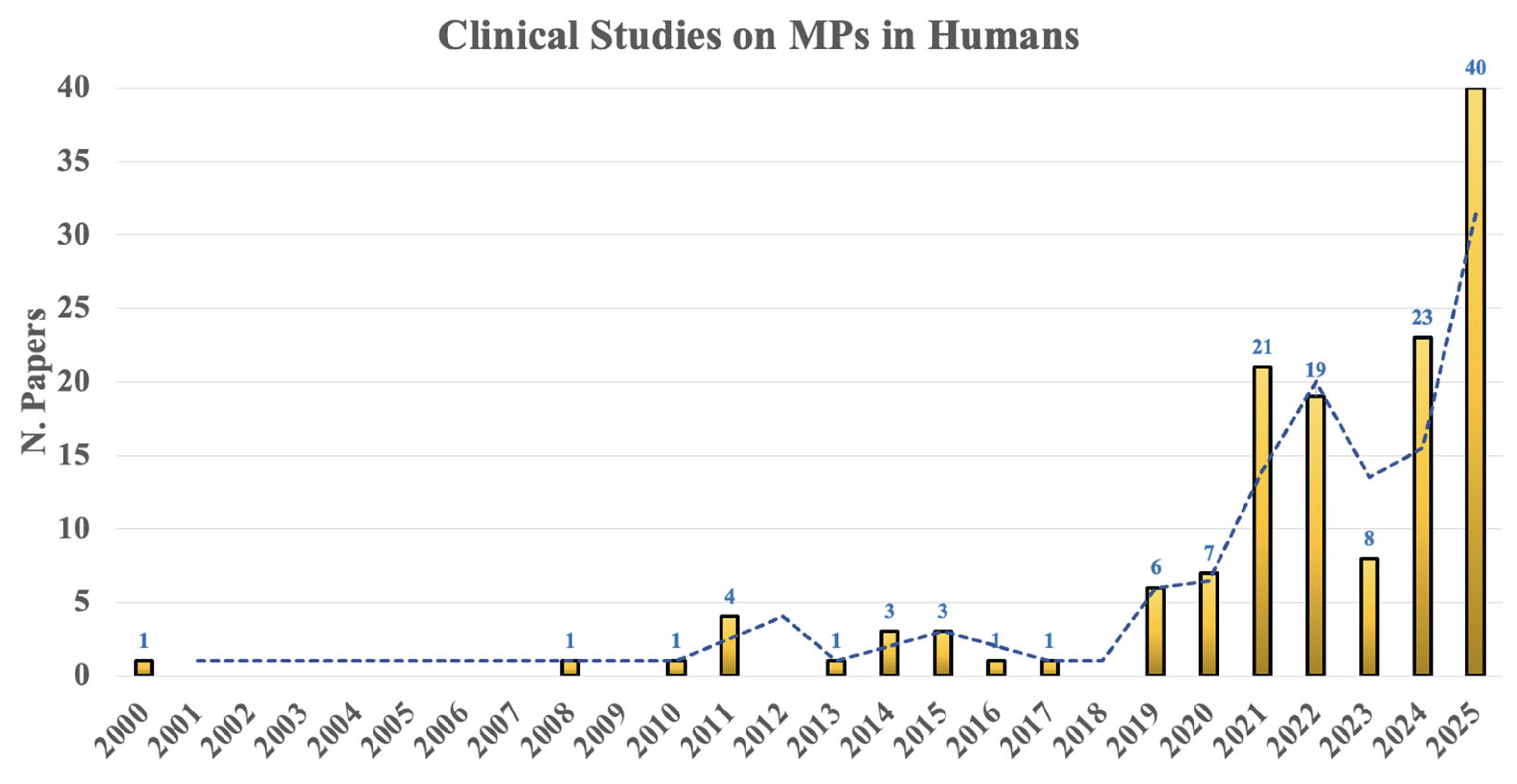

2.1. Methodological Approach/Literature Search

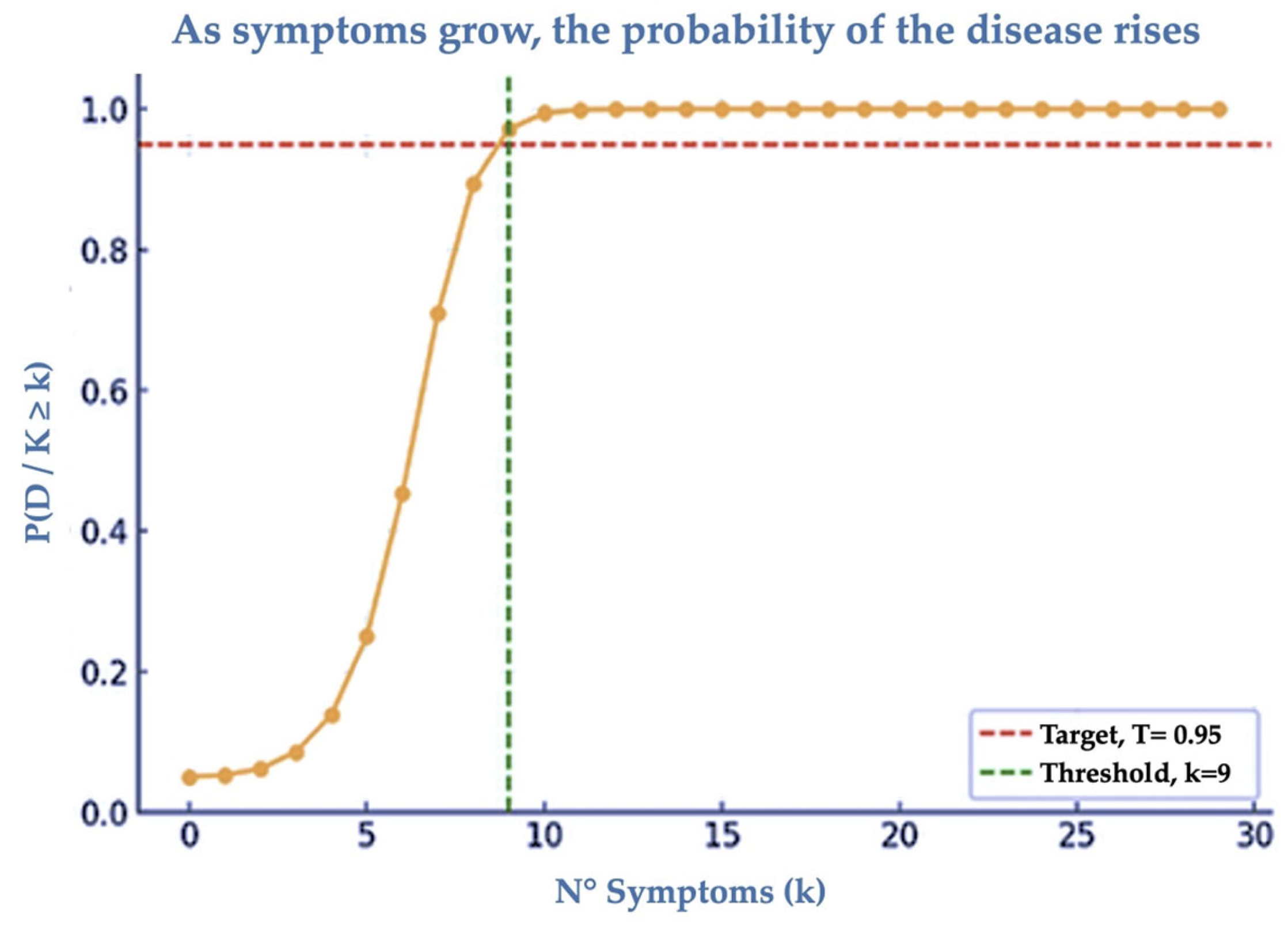

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

3.2. Map of the Organ/System Affected by MNPs

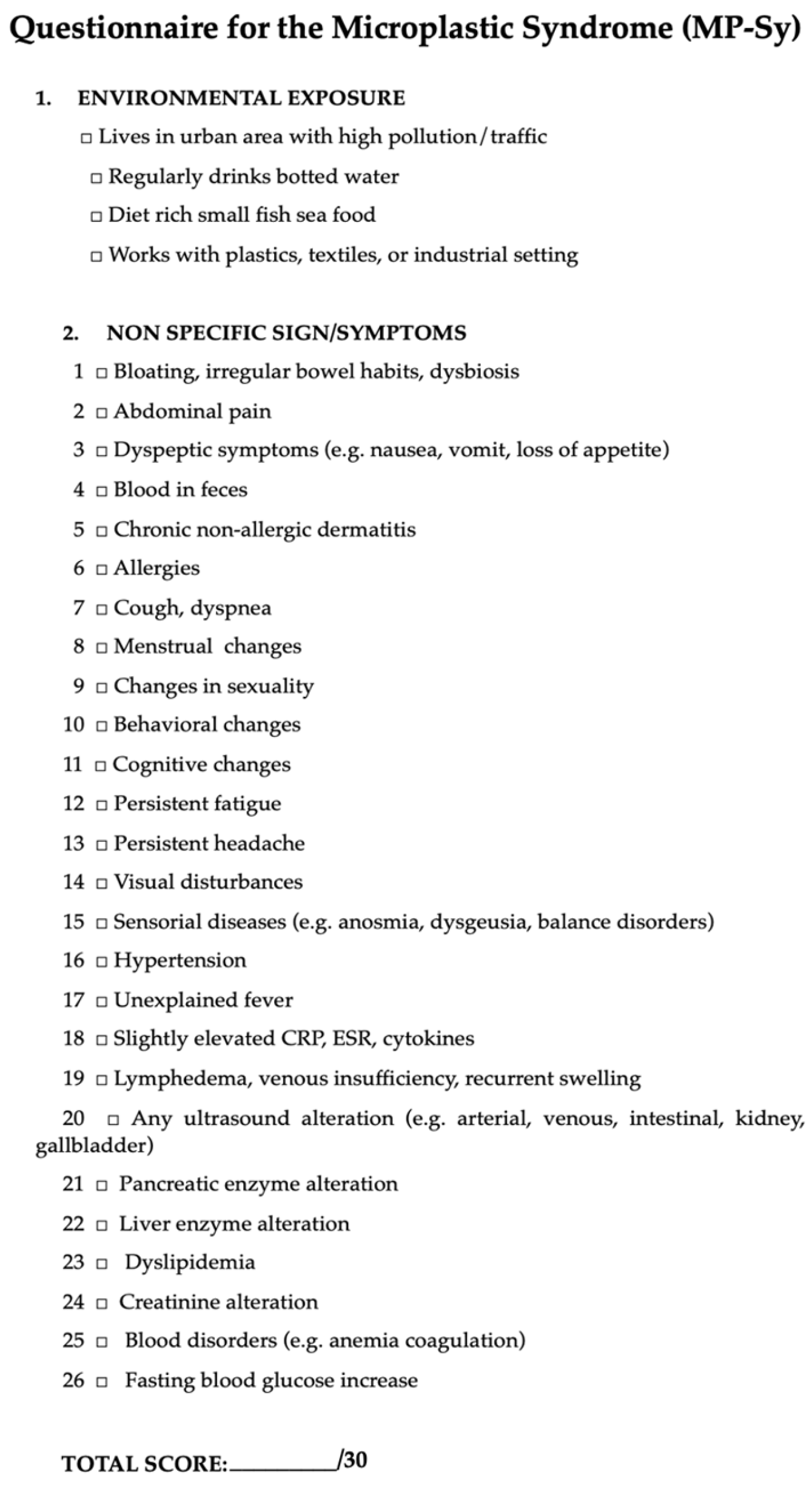

3.3. MNPs Syndrome (MP-Sy)

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Epidemiological Outcomes

4.2. Pathophysiological Processes

4.3. Effects on Therapy and Prevention

4.4. Proposal for Diagnostics and Limitations

4.5. Compared to Other Syndromes

4.6. Concluding Remarks

5. Putative Limitations and Methodological Considerations

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| CCES | Chicago Cluster Evaluation System |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DVT | Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| EDCs | Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| ISTAT | Italian National Institute of Statistics |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MNPs | Micro-Nanoplastics |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| MP-Sy | Microplastic Syndrome |

| Mt | Metric Tons |

| NPs | Nanoplastics |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PVC | Polyvynil Chloride |

| SMRs | Standardized Mortality Rates |

| TBC | Tuberculosis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Casella, C.; Ballaz, S.J. Genotoxic and neurotoxic potential of intracellular nanoplastics: A review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 1657–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastic Europe 2024 Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024 Plastics Europe. 2024. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Haque, M.K.; Uddin, M.; Kormoker, T.; Ahmed, T.; Zaman, M.R.U.; Rahman, M.S.; Tsang, Y.F. Occurrences, sources, fate and impacts of plastic on aquatic organisms and human health in global perspectives: What Bangladesh can do in future? Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5531–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J. Micro (nano) plastics in the human body: Sources, occurrences, fates, and health risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3065–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, G.; Abdulkadhim, M.; Joshi, K.; Wankhede, L.; Das, R.K.; Brar, S.K. Exposure Pathways, Systemic Distribution, and Health Implications of Micro-and Nanoplastics in Humans. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, R.; Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Xia, Y.; Luo, Y. A systematic review of the impacts of exposure to micro-and nano-plastics on human tissue accumulation and health. Eco-Environ. Health 2023, 2, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, S.; Ruffolo, S.A.; Lofaro, D.; Perri, A.; La Russa, M.F. Endocrine Toxicity of Micro-and Nanoplastics, and Advances in Detection Techniques for Human Tissues: A Comprehensive Review. Endocrines 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.; Visalli, G.; Facciolà, A.; Saija, C.; Bertuccio, M.P.; Baluce, B.; Di Pietro, A. Sterile inflammation induced by respirable micro and nano polystyrene particles in the pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 13, tfae138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F.; Sarker, D.B.; Jocelyn, J.A.; Sang, Q.X.A. Molecular and cellular effects of microplastics and nanoplastics: Focus on inflammation and senescence. Cells 2024, 13, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizzolo, M.; Martins, V.H.; Ghelli, F.; Squillacioti, G.; Bellisario, V.; Garzaro, G.; Bergamaschi, E. Biomarkers of oxidative stress, inflammation, and genotoxicity to assess exposure to micro-and nanoplastics. A literature review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 267, 115645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, C.; Cornelli, U.; Ballaz, S.; Zanoni, G.; Merlo, G.; Ramos-Guerrero, L. Plastic Smell: A Review of the Hidden Threat of Airborne Micro and Nanoplastics to Human Health and the Environment. Toxics 2025, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasse, G.F.; Melgert, B.N. Microplastic and plastic pollution: Impact on respiratory disease and health. Eur. Respirat. Rev. 2024, 33, 230226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaran, B.; Özçifçi, Z.; Akcay, H.T.; Aytan, Ü. Microplastics in branded milk: Dietary exposure and risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Basantes, M.F.; Conesa, J.A.; Fullana, A. Microplastics in honey, beer, milk and refreshments in Ecuador as emerging contaminants. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, E.; Niero, G.; Benetti, F.; Perini, A.; Zanella, M.; Pozza, M.; De Marchi, M. Preliminary characterization of microplastics in beef hamburgers. Meat Sci. 2024, 217, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberghini, L.; Truant, A.; Santonicola, S.; Colavita, G.; Giaccone, V. Microplastics in fish and fishery products and risks for human health: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.J.; Moon, N.; Kim, J.H. A systematic review and quality assessment of estimated daily intake of microplastics through food. Rev. Environ. Health 2025, 40, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Azmi, A.A.; Wan Mohd Khalik, W.M.A.; Lehata, S.; Hamzah, S.R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Raps, H.; Cropper, M.; Bald, C.; et al. The Minderoo-Monaco commission on plastics and human health. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, A.; Molinero, N.; Reinosa, J.J.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Portela, R.; Bañares, M.A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. PET microplastics affect human gut microbiota communities during simulated gastrointestinal digestion, first evidence of plausible polymer biodegradation during human digestion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, C.E.; Anderton, R.S.; Gorecki, A.M. Mind over microplastics: Exploring microplastic-induced gut disruption and gut-brain-axis consequences. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4186–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhi, F. Lower level of bacteroides in the gut microbiota is associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5828959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal, M.; Jiménez-Orrego, K.V.; Caicedo-León, M.D.; Páez-Cárdenas, L.S.; Castellanos-García, I.; Villalba-Moreno, D.L.; Gold, M. Microplastics in dermatology: Potential effects on skin homeostasis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, M.S.L.; Hii, L.W.; Looi, C.K.; Lim, W.M.; Wong, S.F.; Kok, Y.Y.; Leong, C.O. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human health. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C. Microplastics and human health: Integrating pharmacokinetics. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; Van Velzen, M.J.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironti, C.; Notarstefano, V.; Ricciardi, M.; Motta, O.; Giorgini, E.; Montano, L. First evidence of microplastics in human urine, a preliminary study of intake in the human body. Toxics 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotchell, J.M.; Austin, C.; Chapman, E.; Atherall, C.A.; Liddle, C.R.; Dunstan, T.S.; Guinn, B.A. Microplastics in human urine: Characterisation using μFTIR and sampling challenges using healthy donors and endometriosis participants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 274, 116208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Jung, J.; Park, S.A.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Han, C.; Hong, Y.C. Microplastic particles in human blood and their association with coagulation markers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Notarstefano, V.; Svelato, A.; Belloni, A.; Gioacchini, G.; Blondeel, C.; Giorgini, E. Raman microspectroscopy detection and characterisation of microplastics in human breastmilk. Polymers 2022, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.T.; Nugrahapraja, H.; Wahyuono, R.A.; Islami, I.; Haekal, M.H.; Fardiansyah, Y.; Luqman, A. Microplastic contamination in the human gastrointestinal tract and daily consumables associated with an Indonesian farming community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of various microplastics in human stool: A prospective case series. Ann. Int. Med. 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Ehrlich, L.; Henrich, W.; Koeppel, S.; Lomako, I.; Schwabl, P.; Liebmann, B. Detection of microplastic in human placenta and meconium in a clinical setting. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, E.; Du, Z.; Peng, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, X. Detection of various microplastics in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 10911–10918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, L.; Weng, J.; Jin, Z.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z. Detection and characterization of microplastics in the human testis and semen. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Huang, X.; Bi, R.; Guo, Q.; Yu, X.; Zeng, Q.; Guo, P. Detection and analysis of microplastics in human sputum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Feng, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J.; Guan, Q.; Yang, X.; Luo, Y. Pigment microparticles and microplastics found in human thrombi based on Raman spectral evidence. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 49, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2022-SDGS-Report_Inglese.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Horvatits, T.; Tamminga, M.; Liu, B.; Sebode, M.; Carambia, A.; Fischer, L.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Dalu, T.; Kadushkin, A.; Singh, J.; Li, R. Coronas of micro/nano plastics: A key determinant in their risk assessments. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.L.; Bose, U.; Ni, D.; Nelis, J.L.D. Unravelling protein corona formation on pristine and leached microplastics. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2024, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotchell, J.M.; Jenner, L.C.; Chapman, E.; Bennett, R.T.; Bolanle, I.O.; Loubani, M.; Palmer, T.M. Detection of microplastics in human saphenous vein tissue using μFTIR: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Wang, F.; Xi, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y. Association of microplastics in human cerebrospinal fluid with Alzheimer’s disease-related changes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.; Symeonides, C.; Raps, H.; Dunlop, S. The global plastics treaty: Why is it needed? Lancet 2023, 402, 2274–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, Y.S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Azmi, A.A.; Wan Mohd Khalik, W.M.A.; Lehata, S.; Hamzah, S.R.; Lee, Y.Y. Detection of microplastics in human colectomy specimens. JGH Open 2021, 5, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of microplastics in human feces reveals a correlation between fecal microplastics and inflammatory bowel disease status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Peng, L.; Huang, H. Microplastics are detected in human gallstones and have the ability to form large cholesterol-microplastic heteroaggregates. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, B.M.; Tuna, A.; Başaran Kankılıç, G.; Koçak, F.M.; Şencan, Z.; Cömert, E.; Bayar Muluk, N. Role of microplastics in chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, D.; Wen, K.; Cai, J.; Huang, Z. Revealing new insights: Two-center evidence of microplastics in human vitreous humor and their implications for ocular health. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihart, A.J.; Garcia, M.A.; El Hayek, E.; Liu, R.; Olewine, M.; Kingston, J.D.; Campen, M.J. Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, N.A.; Munk, A.S.F.; Lundgaard, I.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic system: A beginner’s guide. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 2583–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lei, J.; Pang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, T. Neurotoxicity of Micro-and Nanoplastics: A Comprehensive Review of Central Nervous System Impacts. Environ. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelli, U.; Algeri, F.; Brignoli, A. The increase of chronic diseases death during COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: The effect of vaccinations. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 16, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Yao, C.; Huang, L.; Liu, N. Environmental neurotoxicity revisited: Evaluating microplastics as a potential risk factor for autism spectrum disorder. Innov. Med. 2025, 3, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, B.J.; Yang, Y.P.; Li, H.; Wang, F. Impact of microplastics on the human digestive system: From basic to clinical. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella, C.; Cornelli, U.; Ballaz, S.; Recchia, M.; Zanoni, G.; Ramos-Guerrero, L. Preliminary Study on PCC-Chitosan’s Ability to Enhance Microplastic Excretion in Human Stools from Healthy Volunteers. Foods 2025, 14, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Sanyal, T.; Kundu, P.; Kumar, R.; Ghosh, D.; Chakrabarti, G.; Das, A. Microplastics as emerging carcinogens: From environmental pollutants to oncogenic drivers. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, P.; Prejbisz, A.; Kuryłowicz, A.; Baska, A.; Burchardt, P.; Chlebus, K.; Bogdański, P. Metabolic syndrome—A new definition and management guidelines. Arter. Hypertens. 2022, 26, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Giorgini, E. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, A.; Matta, M.; Cristiano, L.; Matassa, R.; Battaglione, E.; Svelato, A.; Nottola, S.A. Deeply in plasticenta: Presence of microplastics in the intracellular compartment of human placentas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Katsouli, J.; Marczylo, E.L.; Gant, T.W.; Wright, S.; De La Serna, J.B. The potential impacts of micro-and-nano plastics on various organ systems in humans. EBioMedicine 2022, 99, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, H.; Moradalizadeh, S.; Jahani, Y.; Nasiri, A. Biomonitoring of microplastics in saliva and hands of young children in kindergartens: Identification, quantification, and exposure assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.R.; Lecka, J.; Pulicharla, R.; Brar, S.K. Microplastic pollution and associated health hazards: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 34, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Agullo, A.; Karanasiou, A.; Moreno, T.; Lacorte, S. Overview on the occurrence of microplastics in air and implications from the use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella, C.; Vadivel, D.; Dondi, D. The current situation of the legislative gap on microplastics (MPs) as new pollutants for the environment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, C.; Cornelli, U.; Zanoni, G.; Moncayo, P.; Ramos-Guerrero, L. Health Risks from Microplastics in Intravenous Infusions: Evidence from Italy, Spain, and Ecuador. Toxics 2025, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashim, J.; Ji, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Jang, S.; Kim, W.; Yu, W. Protein Microplastic Coronation Complexes Trigger Proteome Changes in Brain-Derived Neuronal and Glial Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 14993–15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, Y. Take-out containers as nano-and microplastics reservoirs: Diet-driven gut dysbiosis in university students. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Rong, M.; Fan, Y.; Teng, X.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Y. The Presence of Microplastics in Human Semen and Their Associations with Semen Quality. Toxics 2025, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, M. Microplastics promote chemoresistance by mediating lipid metabolism and suppressing pyroptosis in colorectal cancer. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2287–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, X.; Yang, L.; Jia, Y.; Song, F.; Ma, G. Microplastics in stools and their influencing factors among young adults from three cities in China: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 364, 125168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, D.; Dou, J.; Liu, Y. Association between long-term exposure of polystyrene microplastics and exacerbation of seizure symptoms: Evidence from multiple approaches. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qu, J.; Jin, H.; Mao, W. Associations between Microplastics in Human Feces and Colorectal Cancer Risk. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 139099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xi, Q.; Weng, Y. Impact of urinary microplastic exposure on cognitive function in primary school children. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; Prattichizzo, F.; Sardu, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Graciotti, L.; Spadoni, T.; Paolisso, G. Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N. Eng. J. Med. 2024, 390, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, L.C.; Rotchell, J.M.; Bennett, R.T.; Cowen, M.; Tentzeris, V.; Sadofsky, L.R. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokos, G.C. The immunology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Costa, F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordás, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, R.; Giovannoni, G. Multiple sclerosis—A review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmeier, C.F.; Criner, G.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P.J.; Bourbeau, J.; Agusti, A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Gabbay, R.A. Introduction and methodology: Standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2022, 46 (Suppl 1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado-Priego, L.N.; Cueto-Ureña, C.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Fibromyalgia: A review of the pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary treatment strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, A.S.; Khurana, J.K. Medical Reference Tools and Pharmaceutical Promotion: A History of Entanglement. Ann. Int. Med. 2025, 178, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Váradi, C. Clinical features of Parkinson’s disease: The evolution of critical symptoms. Biology 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallahi, P.; Elia, G.; Ragusa, F.; Paparo, S.R.; Patrizio, A.; Balestri, E.; Ferrari, S.M. Thyroid autoimmunity and SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Assessing National Capacity for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Report of the 2021 Global Survey; World Health Organization: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=OaIOEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Fact+sheet:+noncommunicable+diseases+2023&ots=p15J-xsQck&sig=fLqXvRb4JunM0GSC_J57jjZFKQo#v=onepage&q=Fact%20sheet%3A%20noncommunicable%20diseases%202023&f=false (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- MSD Manual. Clinical Reference. 2025. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Mehra, A.; Khanna, J.; Singh, G.; Sachdeva, V.; Bedi, N. A Comprehensive Review on Major Depressive Disorder: Exploring Etiology, Pathogenesis and Clinical Approaches. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic. Health Information Resource. 2025. Available online: https://monument.health/mayo-clinic-health-information-library/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Puledda, F.; Silva, E.M.; Suwanlaong, K.; Goadsby, P.J. Migraine: From pathophysiology to treatment. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 3654–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenot, P.J. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. 2023. Available online: https://www.merckmanuals.com/en-ca/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/disorders-of-urination/control-of-urination (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Nguyen, N.N.; Tissot-Dupont, H.; Brouqui, P.; Gautret, P. Post-COVID syndrome in symptomatic COVID-19 patients: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2025, 25, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Infectious Diseases. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Cecchetti, M.; Scarallo, L.; Lionetti, P.; Ooi, C.Y.; Terlizzi, V. Impact of highly effective modulator therapy on gastrointestinal symptoms and features in people with cystic fibrosis. Paediat. Respir. Rev. 2025, 54, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.S.; Pereira, I.A.; Sztajnbok, F.; Rosa Neto, N.S. Sarcoidosis: A general overview. Adv. Rheumatol. 2024, 64, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Isaacson, R.S.; Knox, S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Rubino, I. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical practice in 2021. J. Prev. Alzheimer Dis. 2021, 8, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, S.; Binet, A.; Téteau, O.; Desmarchais, A.; Papillier, P.; Lacroix, M.Z.; Elis, S. Bisphenol S impaired human granulosa cell steroidogenesis in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelouahab, N.; Langlois, M.F.; Lavoie, L.; Corbin, F.; Pasquier, J.C.; Takser, L. Maternal and cord-blood thyroid hormone levels and exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated biphenyls during early pregnancy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Zhan, D.; Fang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; Wang, L. Microplastics, potential threat to patients with lung diseases. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 958414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Disease | SMRs Values (×104); Means ± SD | p c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2022 | ||

| Blood and hematopoietic a | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | <0.05 |

| Endocrine system (excluding diabetes) | 0.79 ± 0.19 | 1.20 ± 0.27 | <0.05 |

| Mental disorders | 1.73 ± 0.59 | 3.50 ± 1.27 | <0.05 |

| Senile dementia a | 1.44 ± 0.54 | 3.21 ± 1.31 | <0.05 |

| Parkinson | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 1.15 ± 0.14 | <0.05 |

| Genito-urinary a | 1.72 ± 0.35 | 1.86 ± 0.29 | >0.05 |

| Unknown a | 0.42 ± 0.61 | 1.66 ± 1.22 | <0.05 |

| Cancers b | |||

| Pancreas | 1.43 ± 0.37 | 1.72 ± 0.22 | <0.05 |

| CNS | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.62 ± 0.10 | <0.05 |

| TOTAL | 109.64 ± 6.62 | 90.73 ± 6.60 | <0.05 |

| Organ/System | Symptoms | Main Laboratory Test |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Anemia, thrombosis | Cell count, coagulation markers |

| Microbiota | Abdominal discomfort, pain, diarrhea, constipation | Inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Arteries | Hypertension | Inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Veins | Insufficiency | Inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Lymphatic | Insufficiency | Inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Pancreas | Abdominal pain | Specific enzymes, inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Liver | Enlarged, hardness | Dyslipidemia, specific enzymes, inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Brain | Anxiety, depression, aggressiveness, sleep disorders, headache, irritability, paranoia | Inflammatory markers, neurological tests, cognitive tests, functional tests, ultrasound |

| Lung | Dyspnea, cough | Inflammatory markers, pulmonary function tests, ultrasound |

| Nose | Rhinosinusitis | Inflammatory markers, ultrasound |

| Eyes | Intraocular pressure, retinal damage | Inflammatory markers, ocular function tests |

| Skin | Irritation, inflammation | Inflammatory markers, images |

| Reproductive | Sexual disorders, menstrual disorders | Hormonal imbalance, sperm modification, inflammatory markers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cornelli, U.; Casella, C.; Belcaro, G.; Cesarone, M.R.; Marucci, S.; Rondanelli, M.; Recchia, M.; Zanoni, G. Definition of Emerging Microplastic Syndrome Based on Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence: A Narrative Review. Microplastics 2025, 4, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040093

Cornelli U, Casella C, Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Marucci S, Rondanelli M, Recchia M, Zanoni G. Definition of Emerging Microplastic Syndrome Based on Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence: A Narrative Review. Microplastics. 2025; 4(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleCornelli, Umberto, Claudio Casella, Giovanni Belcaro, Maria Rosaria Cesarone, Simonetta Marucci, Mariangela Rondanelli, Martino Recchia, and Giuseppe Zanoni. 2025. "Definition of Emerging Microplastic Syndrome Based on Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence: A Narrative Review" Microplastics 4, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040093

APA StyleCornelli, U., Casella, C., Belcaro, G., Cesarone, M. R., Marucci, S., Rondanelli, M., Recchia, M., & Zanoni, G. (2025). Definition of Emerging Microplastic Syndrome Based on Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence: A Narrative Review. Microplastics, 4(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040093