Abstract

External fixation is widely used in trauma care for managing bone and soft tissue injuries. These devices are often associated with psychological challenges and are often not followed up with sufficient psychological support for the patient. The specific psychological impact of external fixation following traumatic injuries remains underexplored. This scoping review aimed to synthesize the current literature on the psychological impact of external fixation in trauma patients. A systematic search of CINAHL, Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and EBSCO identified ten studies (2006–2024), from the USA, Europe, Asia, and Oceania to be included based on inclusion criteria of using the device for traumatic injuries (excluding limb lengthening procedures) and assessing psychological outcomes using validated tools. Data extracted included injury type, fixator application, survey type, and mental health outcomes. Common measures included HADS, SF-36/SF-12, PedsQL, CRIES-13, EQ-5D-5L, and patient-reported questionnaires. The findings showed that elevated psychological distress was greatest during early recovery (~1 month). Body image concerns were frequently reported with the fixator in place; however, partial recovery of mental health scores was seen by 12–24 months. These findings emphasize the need for additional research and a greater integration of mental health resources in trauma care protocols involving external fixation.

Keywords:

external fixation; external fixator; orthopedic trauma; mental health; anxiety; depression 1. Introduction

External fixator devices have been used as a treatment option for the management of traumatic injuries, particularly fractures. Although external fixators have been utilized for thousands of years, dating back to the ancient Greeks, advancements in their design and biomechanics have significantly evolved. These devices are primarily used to facilitate fracture alignment and stabilization [1]. This tool was once used as the last option to traumatic injuries, especially those that involved an edematous limb that precluded casting [2]. More recently, external fixators have been used for indications beyond fractures, including limb lengthening procedures and complex open fractures such as knee dislocations, multi-ligament knee injuries, and fractures involving other joints, such as the elbow [1,2,3]. There are several construct variations for external fixation devices, including uniplanar or multiplanar, circular, and unilateral or bilateral, each with its own indications.

Given the appropriate clinical context, external fixation devices can be an important tool in the treatment armamentarium of the orthopedic surgeon. For example, these devices can enable serial management of soft-tissue injuries around fractures [2]. They can even allow for earlier mobility of the limb, compared to a cast [1,4]. External fixation is especially beneficial for polytraumatized patients, as it provides rapid stabilization of the injured region in patients who may have more serious injuries that must be prioritized [5].

Unfortunately, the burden associated with trauma extends beyond physical repercussions. Orthopedic trauma has been shown to cause psychological distress in patients, potentially resulting in high levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD, which may persist for years after surgical treatment [2]. Recognizing the significance of psychological recovery is vital to delivering comprehensive trauma care, particularly for patients undergoing major orthopedic interventions, such as external fixation. Poor function following orthopedic surgery has also been shown to be correlated with poor mental health [2]. As with many orthopedic surgeries, psychological impact is understudied, even though these procedures can be burdensome. Due to the absence of research within this area, patients often receive insufficient psychological support after application of an external fixator. Without adequate support, patients are often left to adjust to the physical and psychological challenges associated with the external fixator on their own [5]. In addition to the physical recovery process that patients must endure with external fixators, there is also the mental and emotional toll patients experience. The bulky and cumbersome nature of these devices has been reported to adversely affect patients’ psychological well-being and mental health [6].

The purpose of this scoping review was to thematically synthesize the existing literature regarding the psychological impact of external fixation in the treatment of traumatic injuries.

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of this scoping review was to evaluate the literature addressing the psychological impact of external fixation in patients treated for traumatic injury.

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using CINAHL, Cochrane Library, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar to identify survey studies published from 2000 to 2025 in which the psychological well-being of patients with external fixator devices was assessed. Search strategies were developed with the assistance of a medical librarian. The gray literature was searched in the following agencies and websites: National Institute of Mental Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Defense Health Agency, Google Scholar, OCLC OAIster Database, EBSCO OpenDissertations, government and institutional websites. Search queries used for PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, and Cochrane Library are detailed in Table 1. The initial search began on 8 June 2025 and concluded on 25 June 2025. This protocol was retrospectively registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF), and can be accessed via DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/6QNDR.

Table 1.

Search Terms and Results for PubMed, PsychInfo, CINHAL, SCOPUS, and Cochrane Library.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

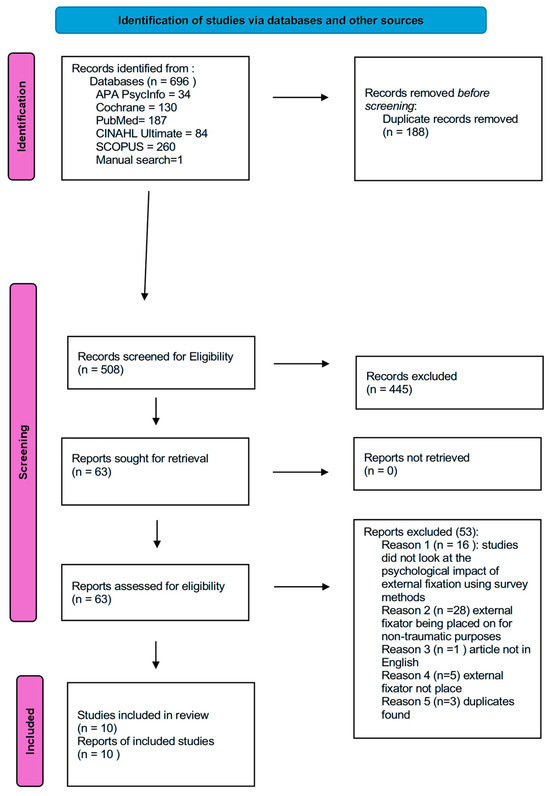

Once all the studies were retrieved, the dataset was exported into PICO portal, an artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled systematic review platform to screen titles and abstracts. Clinical studies were included if the following criteria were met: the study population included only participants with external fixators placed due to fractures from traumatic injuries (1), mental and emotional well-being was assessed (2), and assessment of psychological impact was in the form of a survey, questionnaire, or interview (3). Studies were excluded if the external fixator was placed for reasons other than traumatic injury, such as limb lengthening, and if the articles were not in English. All studies were independently screened by two reviewers (M.N. and E.A.), with a third reviewer (M.M) consulted to resolve any discrepancies. The selection process is summarized in PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), which outlines the number of studies excluded during each stage. A final sample of ten studies were eligible using inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for identification of studies via databases and registers.

2.3. Data Extraction

For each of the studies, the study country and design as well as age, body part of injury, reason for external fixation and description of the injury, survey tools used, and results were extracted. Table 2 presents the authors, study country, study design, and types of survey methods used in the studies.

Table 2.

General characteristics of included studies.

3. Results

A total of 696 potential studies were identified. After removing 188 duplicates, 508 results were screened for eligibility based on the abstract. Studies that did not examine the psychological impact of external fixations were then removed. The remaining 63 studies were then re-screened. An additional 53 studies were removed for one of five different reasons: (1) study did not look at the psychological impact of the external fixation using survey methods (2) external fixation was placed for non-traumatic reasons such as limb lengthening (3) article was not English (4) external fixation was not used (5) duplicates were found. Finally, a total of 10 studies were assessed that met the inclusion criteria and were therefore included in the scoping review.

The 10 included studies, published from 2006 to 2024, were from the United States, Denmark, Sweden, Australia, UK, China, and Pakistan. All studies included a component of assessing psychological outcomes in patients that underwent external fixation due to a traumatic injury. Studies that described external fixators placed for congenital deformities or limb lengthening procedures were removed. This was to ensure that this scoping review maintained a homogenous population when evaluating the impact of external fixation in an acute trauma setting. Each of the general characteristics of the study (author, publication year, study country, study designs, and tools used to measure psychological impact) are all labeled in Table 2. Thematic analysis of each of the studies also revealed three recurring themes between the 10 studies.

3.1. Psychological Distress Within the Early Stages

One of the first themes identified was the psychological distress experienced by patients, specifically during the early post-operative period. In on qualitative study, adolescents were interviewed about their experience after external fixator placement [7]. They described a loss of control over daily activities such as movement and dressing. Participants reported being able to regain some autonomy in small ways such as being able to control their own room setting and routine within the hospital. However, as they adapted to life with the device, the patients described regaining a sense of independence through actions such as using the bathroom unaided or independently managing their pain [7]. According to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) that was given to patients, the scores from the pre-operative group (5.18 ± 1.17) to the 7th day postoperative (7.31 ± 1.47), the scores in both anxiety and depression increased. Notably, the external fixator group had the highest anxiety scores (9.49 ± 2.29) after the first month post-surgery [12]. Additionally, with the same HADS survey given to patients, a similar trend is seen in patients regarding depression scores, increasing from a pre-operation score of 4.28 ± 1.30 to a score of 6.69 ± 2.42 at 7 days post-operation (Table 3). Patients had the highest depression scores at the 1st month post operation as well [12].

Table 3.

HADS-Anxiety and Depression Scores over time in External Fixation Group (Data from Jia et al. [12]). Note: Higher scores indicate worse depression and anxiety.

When the mental component of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) was administered to patients with an external fixator device, their scores showed a statistically significant difference compared to patients with internal fixator device [12]. By day 7 post operation, the mean mental component score (MCS) was significantly higher in those with the internal fixator device compared to those with an external fixator device. Specifically, the lowest mean score for the external fixator group was during the first month post-surgery, with a significant difference from its internal fixator group counterpart (Table 4). The SF-36 scores are consistent with findings from the HADS survey, corroborating that psychological distress is seen in patients, especially in early months post external fixator placement [12].

Table 4.

Statistically Significant Mental Component Scores of the SF-36 in the external fixator group (EFG) and internal fixator group (IFG) group (data from Jia et al. [12]). Note: higher scores indicate better mental well-being.

The Children’s Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES) was used to assess PTSD symptoms in pediatric patients following traumatic injury, comparing outcomes between those treated with external fixators and those treated with casts [16]. Compared to the children who wore a cast, those with an external fixator demonstrated more variable outcomes and showed less improvement over time [16]. Scores above 30 indicate a significant risk for PTSD, but most children in the cast group had scores below 30 after the first month. While the frame group had a similar downward trend, approximately 25% of children with external fixators continued to score above 30. A statistically significant improvement was observed only in the cast group [16].

3.2. Body Image Disturbances and Post Traumatic Stress

Several studies have also assessed the altered self-image caused by external fixators. Using Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale at three time points, including hospital discharge, six months after frame applications, and at the time of frame removal, there was a 12% decline in self-esteem scores, which was statistically significant [13]. An additional study with adolescents pointed to the multiple changes in their body image. Adolescents wearing the external fixation device reported experiencing public attention, often in the form of unsolicited glances from others, bringing up feelings of not feeling like their “old self”. Some even described themselves as looking “robotic”, especially those who had never seen an external fixation device before [6]. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PEDSQL) was used to assess health-related quality of life in children who experienced lower limb pediatric trauma [15]. Using a cutoff of under 80 to indicate reduced quality of life, results showed children assessed with the PEDSQL, less than 12 months, post injury had a median total score of 73, with a physical component of 78 and psychosocial component of 75. After more than 12 months post injury, the median score improved to approximately 81 for physical and 80 for both the total and the psychosocial score. The scores showed that there was a high incidence of post-traumatic stress using the self-reported scores from the PEDSQL [15].

3.3. Adjustment in the Long-Term

Though the psychological impact of the external fixator persists during treatment and several months thereafter, studies do suggest that patients gradually adapt and accept the long-term consequences that the treatment had brought. By using the mental health component scores (MCS) of the SF-36 in patients from 1 month post injury till 2 years post injury, scores were shown to increase from the initial time point of one month post injury with the 2-year mark demonstrating scores that were like normal age matched (Table 5) [9]. It was also observed that the scores for the MCS component of the SF-36 had a significant increase compared to previous scores from 3 months post injury and 6 months post injury [8]. Other research has also shown that as time progresses post injury, the mental health scores have increased with the lowest score being the first month post-surgery for the external fixator device [12].

Table 5.

Scores of Mental Component Scores of time points 1 month, 3 months, and 24 months (Data from Marsh et al. [14]). Note: higher scores indicate better mental well-being.

Patients that had a tibial plafond fracture had lower average scores on the mental and physical component of the SF-36 compared to the U.S population norms; however, these differences were not reported as statistically significant [14]. The mental component showed a score of 49 compared to the U.S norm of 53 at around 2 years post external fixator device placement [14]. Using the PEDQL, the median total score among children post-injury improved from 73 to 81 after more than 12 months, with scores below 80 indicating reduced health-related quality of life [15]. Though several studies showed the improvement of mental health scores in patients undergoing external fixation, some studies demonstrated that even after 12 months after frame removal the mean 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ5D-5L) score was 69 (SD = 24.4) [8]. The authors noted that compared to the normal values for Denmark, the EQ5D-5L scores were much lower [8].

4. Discussion

This scoping review identified three key themes in the literature regarding the psychological impact of external fixation on patients with traumatic injuries: psychological distress experienced during early recovery, body image disturbance and post-traumatic stress symptoms, and eventual long-term psychological adjustment. These themes highlight common psychological patterns in these patients, potentially influenced by the visibility and bulkiness of the device.

Previous research has shown a negative psychological impact that orthopedic surgeries can have on a patient with traumatic injuries [17]. These findings align with the results of this scoping review, in which patients with external fixation similarly reported experiencing immediate psychological distress. It is important to note that the level of psychological impact of external fixation can be attributed to differences in injury patterns, rehabilitation access, or even patient demographics. Compared to internal fixation devices, the external fixation devices have greater significant psychological impact on patients.

The external fixator’s visible and bulky appearance appeared to contribute significantly to the negative body image and self-esteem patients’ experiences. Patients, specifically adolescents, acknowledge the bulkiness of the device and its impact in public situations, particularly due to unwanted attention and staring. The bulkiness of the device makes it harder for patients to cover up the device with clothing and not only restricts mobility, but also serves as a constant reminder of the traumatic event, potentially exacerbating emotional distress and body image disturbances [7]. It was also shown that self-esteem scores declined while wearing the device [13]. These findings suggest that the visible nature of external fixation may contribute to declines in self-esteem and body image during treatment.

Though studies show the negative impact of external fixation on patients, these impacts are often seen to gradually improve. Multiple studies demonstrated that mental health scores often showed improvement over time, particularly within one to two years post-treatment [12,14]. However, even after 12 months post frame removal, the quality-of-life scores remained significantly lower than the general population [8]. Over time, most patients were seen to adapt and return to normal levels in mental health surveys. This variation can be attributed to multiple different factors like social support and healthy coping mechanisms or even access to rehabilitation.

These findings suggest a need for multidisciplinary care approaches that will incorporate psychological screening in patients undergoing external fixation device placement after a traumatic injury. Further research is needed to explore how the frame characteristics like size and location, patient demographics, access to rehabilitation resources can impact the psychological impact of the external fixator device.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review is one of the few studies that systematically assessed psychological outcomes in patients treated with external fixator devices, utilizing validated assessment tools. By synthesizing the current evidence, this review identifies important gaps in the literature looking at the psychological impact on patients treated with external fixator devices.

However, this study has several limitations. Only ten articles were able to meet the inclusion criteria, which limits the breadth of the available evidence. Due to the small number of included studies, the stratification of psychological outcomes was not able to be stratified by frame size or anatomical location, both factors that may significantly influence mental health. Most of the articles used validated survey tools such as the SF-36, it is unclear whether unmeasured confounders, such as prior psychiatric history or social history, may have influenced the results.

Future studies should consider stratifying results based on the specific frame characteristics like size and anatomical location. This may lead to a better understanding of how these factors influence psychological outcomes in patients treated with external fixator devices. While this scoping review aimed to map the psychological impact of external fixation on patients with traumatic injuries, it became evident that there is limited research in this topic. As such, this review highlights a need for more comprehensive research in this area to fully understand the psychological impact associated with external fixation. Addressing this will enable physicians to incorporate more patient-centered care and improve overall treatment outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review aimed to thematically synthesize the literature related to the psychological impact of external fixator devices on traumatic patients, specifically those undergoing this treatment due to traumatic injuries. This review identified three core themes, including psychological distress in the early stages of recovery, body image disturbances and PTSD in patients, and adjustment in the long term, across the literature on this topic. However, future research should continue to explore postoperative psychological distress to support patient-centered care and emphasize the integration of both physical and mental health recovery in orthopedic surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.N. and M.J.M.; methodology, M.V.N., E.M.A., M.J.M.; formal analysis, M.V.N., E.M.A., M.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.N., E.M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.J.M., B.Z., C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xueying Ren for her assistance with our literature search.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Erwin, E.R.; Ray, K.S.; Han, S. The Hidden Impact of Orthopedic Surgeries: Examining the Psychological Consequences. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2023, 47, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, D.C.; Franklin, P.D.; Ring, D.C. The Role of Emotional Health in Functional Outcomes After Orthopaedic Surgery: Extending the Biopsychosocial Model to Orthopaedics: AOA Critical Issues. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2013, 95, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, E.M.; Nair, M.; Levitt, S.J.; Levy, B.A.; Medvecky, M.J. Knee-Spanning External Fixation in the Management of Knee Dislocations and Multiligamentous Knee Injuries: A Narrative Review. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2025, 16, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, E.M.; Levitt, S.; Abrams, G.D.; Stannard, J.P.; Medvecky, M.J. The Role of Hinged External Fixation in the Treatment of Knee Dislocation, Subluxation and Fracture-dislocation: A Systematic Review of Indications. J. Exp. Orthop. 2025, 12, e70275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bible, J.E.; Mir, H.R. External Fixation: Principles and Applications. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragomen, A.T.; Rozbruch, S.R. The Mechanics of External Fixation. HSS J.® Musculoskelet. J. Hosp. Spec. Surg. 2007, 3, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.M. Adolescent Experience with Traumatic Injury and Orthopaedic External Fixation: Forever Changed. Orthop. Nurs. 2010, 29, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsoe, R.; Larsen, P.; Petruskevicius, J.; Kold, S. Complex Tibial Fractures Are Associated with Lower Social Classes and Predict Early Exit from Employment and Worse Patient-Reported QOL: A Prospective Observational Study of 46 Complex Tibial Fractures Treated with a Ring Fixator. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2018, 13, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.L.; McKinley, T.; Dirschl, D.; Pick, A.; Haft, G.; Anderson, D.D.; Brown, T. The Sequential Recovery of Health Status after Tibial Plafond Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2010, 24, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modin, M.; Ramos, T.; Stomberg, M.W. Postoperative Impact of Daily Life after Primary Treatment of Proximal Distal Tibiafracture with Ilizarov External Fixation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3498–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonato, L.J.; Edwards, E.R.; Gosling, C.M.; Hau, R.; Hofstee, D.J.; Shuen, A.; Gabbe, B.J. Patient Reported Health Related Quality of Life Early Outcomes at 12 Months after Surgically Managed Tibial Plafond Fracture. Injury 2017, 48, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.; Peng, Z.; Huang, A.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, W.; Xie, Z.; Ma, C. Is Fracture Management Merely a Physical Process? Exploring the Psychological Effects of Internal and External Fixation. J. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Siddiqui, F.; Bashar, M.; Adeel, M.; Rajput, I.M.; Katto, M.S. Impact of Ilizarov Fixation Technique on the Limb Functionality and Self-Esteem of Patients with Unilateral Tibial Fractures. Cureus 2019, 11, e5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, J.L.; Muehling, V.; Dirschl, D.; Hurwitz, S.; Brown, T.D.; Nepola, J. Tibial Plafond Fractures Treated by Articulated External Fixation: A Randomized Trial of Postoperative Motion versus Nonmotion. J. Orthop. Trauma 2006, 20, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, J.; Harwood, P.; Johnson, L.; Itte, V.; Bourke, G.; Foster, P. Lower Limb Paediatric Trauma with Bone and Soft Tissue Loss: Ortho-Plastic Management and Outcome in a Major Trauma Centre. Injury 2020, 51, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L.; Messner, J.; Igoe, E.J.; Foster, P.; Harwood, P. Quality of Life and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Paediatric Patients with Tibial Fractures during Treatment with Cast or Ilizarov Frame. Injury 2020, 51, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, M.; Busse, J.; Hanson, B.; Leece, P.; Ayeni, O.; Schemitsch, E. Psychological Distress and Quality of Life after Orthopedic Trauma: An Observational Study. Yearb. Orthop. 2009, 2009, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).