Abstract

Background/Objectives: Early diagnosis and surgical intervention are critical in upper extremity (UE) compartment syndrome to prevent irreversible muscle necrosis or amputation. Despite its prevalence, there remains limited literature guiding surgical management or predictors of complications. This study aims to characterize risk factors and outcomes following UE fasciotomies. Methods: A 14-year (2010–2024) retrospective review was conducted of adult patients undergoing fasciotomies for UE compartment syndrome at a level 1 trauma center. Exclusion criteria included age <18 years, incomplete records, or fasciotomies not performed for compartment syndrome. Data collected include demographics, injury mechanism, presenting symptoms, and diagnostic methods. Intraoperative details obtained include incision type, number of interventions, closure method, presence of muscle necrosis, and amputation. Results: Fifty-five patients (58 extremities) met the inclusion criteria (median age 42 years; 85% male). Mechanisms included fractures (29.3%), prolonged pressure (“found-down”) (25.9%), vascular injuries (13.8%), ballistic trauma (8.6%), crush (6.9%), and other (15.5%). Common symptoms were pain (72.4%), paresthesias (48.3%), and motor dysfunction (43.1%). Isolated fasciotomy incisions included volar forearm (41.4%), hand (8.6%), dorsal forearm (3.4%), and upper arm (1.7%), with the remaining being combinations thereof. Among the 40 total volar forearm fasciotomies, none developed postoperative dorsal forearm muscle necrosis. Muscle necrosis (19%) was associated with pallor (p = 0.05) and pulselessness (p < 0.001). A prolonged pressure mechanism was associated with increased muscle necrosis (p = 0.02) and amputation (p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the fracture mechanism was associated with decreased muscle necrosis (p < 0.001) and higher DPC rates (p < 0.001). Conclusions: Pain, paresthesias, and motor dysfunction were most common symptoms in UE compartment syndrome; pallor and pulselessness correlated with muscle necrosis, indicating advanced compartment syndrome. The prolonged pressure mechanism was associated with greater muscle necrosis and amputation, while fracture-related mechanisms were associated with decreased muscle necrosis and higher DPC rates.

1. Introduction

Early diagnosis and surgical intervention are critical in cases of upper extremity (UE) compartment syndrome to decrease the risk of irreversible muscle necrosis, neural dysfunction or possible amputation. Compartment syndrome may occur following trauma, vascular injuries, fractures, or with reperfusion after vascular repair; moreover, additional attention has been brought to compartment syndrome recently due to its high incidence following combat-related injuries in the current geopolitical environment [1].

While the general principles of management for compartment syndrome are well established, particularly for the lower extremity [2,3,4], there remains a dearth of clinical data guiding management of UE injuries. The diagnostic utility of the commonly cited “5 P’s” (pain, paresthesias, paralysis, pallor, and pulselessness) has been debated [5]. Of the limited literature describing fasciotomy incision planning, such as whether targeted single compartment fasciotomies are adequate or whether fasciotomies of multiple adjacent compartments are required [6,7], there remains a lack of consensus regarding the effect of these surgical techniques on clinical outcomes. Additionally, few studies have investigated risk factors for complications such as requiring graft or flap coverage, developing muscle necrosis, or requiring secondary amputation.

This study aims to describe clinical characteristics, operative approach, and identify independent risk factors for failing delayed primary closure, developing muscle necrosis, or requiring secondary amputation in those with UE compartment syndrome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

A 14-year (2010–2024) retrospective review of adult patients (age > 18) undergoing UE fasciotomies for compartment syndrome was conducted at the Harborview Medical Center Level I trauma center. Patients were identified using a combination of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for UE compartment syndrome and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for UE fasciotomy procedures. Exclusion criteria included age < 18 years, incomplete records, or fasciotomies performed for indications other than compartment syndrome.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Interventional Review Board of the University of Washington.

2.2. Data Collection

Chart review was performed to demographic data, injury mechanism, clinical symptoms at time of presentation, and diagnostic method employed. Operative details, including fasciotomy incisions, concomitant carpal tunnel release, number of operative dates, presence of muscle necrosis intraoperatively, and method of closure, were collected.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Clinical variables, intraoperative findings, and outcomes were tabulated using parametric analyses as appropriate. Continuous data were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD), while binary data was expressed as a number and percentage. A priori power calculation could not be performed given the prevalence of compartment syndrome and that rates of adverse outcomes are not well described. The two-tailed threshold for statistical significance was set at an alpha value of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort

A total of 55 patients (47 male [85%] and 8 female [15%]) comprising 58 upper extremities met the criteria for inclusion in the final analysis. The mean age was 42.9 years (SD ± 13.9). The predominant injury mechanism causing compartment syndrome was a fracture (n = 17, 29%), followed by a prolonged pressure (“found-down”) mechanism (n = 15, 26%). Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients who underwent UW fasciotomies.

3.2. Physical Examination at Presentation

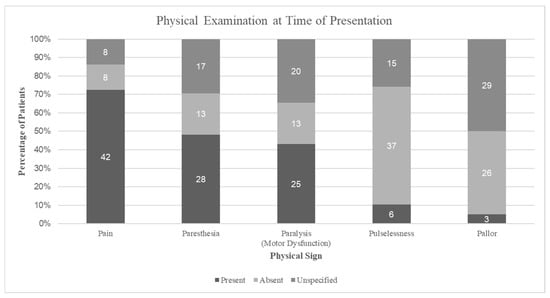

Compartment syndrome diagnosis was primarily clinical (n = 50, 86%), though needle pressure measurements were performed in eight cases (14%) when clinical findings were equivocal or the patient was unable to participate in an awake examination. On presentation, the most common symptom was pain with passive motion or out of proportion to exam (72.4%), followed by paresthesias (48.3%), motor dysfunction (43.1%), pulselessness (10.3%), and pallor (5.2%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physical examination findings at presentation, showing the proportion of patients with each traditional signs, documented as present, absent, or unspecified.

3.3. Operative Approach and Intraoperative Findings

Overall, the median number of operations was 3 (range 1–9). The median time from presentation to fasciotomy was 361 min (range 66–8056) and the median time from fasciotomy to closure was 7 days (range 0–245). In the primary closure subcohort, patients required fewer operations, with a median of 2.5 operations (range 1–5), and had a shorter average time interval to closure of 5.2 days (SD ± 4.3). Carpal tunnel release (CTR) was performed in 39 (67%) extremities in total, of which 22 were performed with an adjunct single-incision fasciotomy and 17 with multiple-incision fasciotomies. Among the 28 extremities that reported paresthesias upon presentation, 19 (50%) underwent carpal tunnel release (15 CTR without hand fasciotomy and 4 with hand fasciotomy), 1 underwent hand fasciotomy alone, and 8 received neither intervention.

The most common isolated fasciotomy type was volar forearm fasciotomy (VFF) (n = 24, 41.4%), followed by hand fasciotomy (HF) (n = 5, 8.6%) and dorsal forearm fasciotomy (DFF) (n = 2, 3.4%). Meanwhile, combined fasciotomies were more often VFF + DFF (n = 10, 17.2%), followed by VFF + DFF + HF (n = 6, 10.3%). Isolated upper arm fasciotomies (AF) (n = 1, 1.7%) and combined DFF + HF (n = 1, 1.7%) were least common. Among the 40 total VFFs, whether in isolation or combination, 31 (77.5%) did not undergo DFF and none developed postoperative dorsal forearm muscle necrosis or required secondary DFF. Operative fasciotomy incision techniques are summarized in Table 2. The method of closure included delayed primary closure (DPC) (62.1%), skin grafting (24.1%), amputation (6.9%), flap coverage (3.4%), or healing by secondary intention (3.4%). Operative closure techniques are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Frequency of fasciotomy incision types.

Table 3.

Frequency of closure techniques.

Necrotic muscle was found intraoperatively in 19% of cases and was significantly associated with pallor (9%, p = 0.05), pulselessness (9%, p < 0.001), and a prolonged pressure mechanism (54.5%, p = 0.02), while fractures were negatively associated (18%, p < 0.001). Among DPC cases, 22% had definitive closure at the first return to the OR, with a mean time of 4.3 days versus 3.3 days in those requiring additional procedures (p = 0.28). Fractures were associated with higher rates of DPC (82%, p < 0.001) and a lower incidence of muscle necrosis (12%, p < 0.001). Conversely, prolonged pressure mechanisms had lower DPC rates (47%, p = 0.11) and higher rates of muscle necrosis (40%, p = 0.02) and amputation (20%, p < 0.001). Single-incision fasciotomies were associated with higher rates of DPC (56%, p < 0.001) and higher rates of muscle necrosis (9%, p = 0.01).

4. Discussion

This study reviews a 14-year period of the clinical presentation, operative management, and closure techniques in patients undergoing fasciotomy for UE compartment syndrome. While the principles of diagnosis and treatment of compartment syndrome are well established, most prior work has focused on the LE, with a limited literature specific to the UE. Our findings address this gap by characterizing clinical exam patterns, operative techniques, and risk factors for complications. These findings highlight the importance of continuous monitoring, expedient fasciotomy release, and incisional planning.

In our study, there was a correlation between the mechanism of injury and development of complications. Specifically, we found a higher rate (29%) of fracture-related injuries compared to some literature, which report an incidence of up to 10% [8,9,10,11]. These patients were significantly more likely to undergo DPC and were associated with lower incidence of necrosis and amputation. This may reflect that fracture patients often sustain a discrete and immediately apparent injury in individuals who are otherwise alert and oriented, which facilitates both earlier diagnosis and treatment. In contrast, patients with a prolonged pressure mechanism of injury are frequently obtunded, often due to intoxication or other medical comorbidities, often resulting in delayed presentation and intervention. These differences in presentation and timeliness of care likely contribute to the time for ischemic injury and necrosis to develop. While fractures have been recognized as a common risk factor for compartment syndrome, due to increased bleeding, swelling, and soft tissue injury within a fixed-volume space [12,13,14,15], greater awareness in these patient associations has prompted closer monitoring practices in such fracture patients and subsequently has hopefully helped decrease the risk of severe sequelae. Together, these findings suggest that the mechanism of injury and patient factors of presentation influence both recognition and outcomes in compartment syndrome.

This study found that while pain with passive motion or stretch was the most sensitive and frequently reported symptom, pallor and pulselessness were significantly associated with muscle necrosis. This pattern and association may suggest that these vascular symptoms indicate a more advanced stage of compartment syndrome, when intracompartmental pressures have already surpassed arterial inflow and critical ischemia has developed. By this point in time, microvascular damage may have already caused irreversible muscle and/or nerve injury. This aligns with prior observations that, while the “five P’s” of compartment syndrome are well established, not all are equally predictive or sensitive of severity or tissue loss [4,5]. As such, this highlights the need for rapid recognition and management, especially before overt signs of impaired perfusion are present.

Regarding the surgical strategy, volar forearm fasciotomy (VFF) was the most common approach, with 41.4% being performed as an isolated VFF. Importantly, none of the patients who underwent isolated VFF subsequently developed dorsal muscle necrosis. This aligns with the literature that demonstrates volar incisions can decompress all three compartments (volar, dorsal, and mobile wad compartments), rendering a separate dorsal incision unnecessary unless specific clinical concerns are present [16]. This finding contributes to the ongoing debate regarding the routine need for dual-compartment release [17,18,19]. Although some authors advocate for combined volar and dorsal approaches to ensure complete decompression, our data support a selective approach in which the extent of fasciotomy decompression is guided by patient-specific clinical and intraoperative findings.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature may introduce selection bias and limits our ability to determine causality. Second, the lack of long-term follow-up precludes assessment of functional outcomes, neurologic recovery, or quality of life following fasciotomy. Third, the sample size remains limited in power to detect small differences between subgroups. Additionally, intraoperative decisions, such as the extent of fasciotomy or use of carpal tunnel release, were based on surgeon preference, which may introduce practice variation.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide valuable insights into the presentation and surgical management of compartment syndrome of the upper extremities. By identifying associations between clinical symptoms, injury mechanisms, and outcomes, we contribute to a growing body of evidence that can inform future treatment algorithms.

Further prospective studies are warranted to validate these findings, assess functional outcomes, and explore the role of early adjunct imaging or pressure monitoring in high-risk populations. As management protocols continue to evolve, greater standardization of surgical technique and wound closure approaches may improve both limb salvage and long-term recovery in patients with upper extremity compartment syndrome.

5. Conclusions

Pain, paresthesias, and motor dysfunction emerged as the most common symptoms of UE compartment syndrome at time of presentation. In contrast, pallor and pulselessness were strongly associated with underlying muscle necrosis, thus signaling a more advanced stage of the condition. Mechanism of injury had an influential role, as prolonged pressure mechanism of injury was linked to higher rates of muscle necrosis and subsequent amputation, while fracture-related mechanisms were associated with lower rates of muscle necrosis and higher rates of DPC. These findings underscore the importance of early symptom recognition and the influence of injury mechanism in guiding timely intervention and anticipating clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.D.R., J.B.F. and Y.K.L.; methodology, S.H.V. and B.J.D.R.; data collection, S.H.V., B.J.D.R. and S.J.K.; data analysis, S.H.V. and B.J.D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.V.; writing—review and editing, S.H.V., B.J.D.R., J.B.F., C.S.C. and Y.K.L.; visualization, S.H.V.; supervision, Y.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington (protocol code STUDY00020956 and date of 23 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact that this was a retrospective review of data that was routinely collected and has no impact on patient management.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UE | Upper Extremity |

| LE | Lower Extremity |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| CPT | Current Procedural Terminology |

| CTR | Carpal Tunnel Release |

| VFF | Volar Forearm Fasciotomy |

| DFF | Dorsal Forearm Fasciotomy |

| HF | Hand Fasciotomy |

| AF | (Upper) Arm Fasciotomy |

| DPC | Delayed Primary Closure |

References

- Gordon, W.T.; Talbot, M.; Shero, J.C.; Osier, C.J.; E Johnson, A.; Balsamo, L.H.; Stockinger, Z.T. Acute Extremity Compartment Syndrome and the Role of Fasciotomy in Extremity War Wounds. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frink, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Krettek, C.; Brand, J.; Hankemeier, S. Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg and Foot. Clin. Orthop. 2010, 468, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, B.J.; Quintana, M.T.; Michael Scalea, T.; DuBose, J.; Feliciano, D.V. Two Urgency Categories, Same Outcome: No Difference After “Therapeutic” vs. “Prophylactic” Fasciotomy. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulmer, T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: Are clinical findings predictive of the disorder? J. Orthop. Trauma 2002, 16, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Keudell, A.G.; Weaver, M.J.; Appleton, P.T.; Bae, D.S.; Dyer, G.S.M.; Heng, M.; Jupiter, J.B.; Vrahas, M.S. Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronel, D.N.; Mtui, E.; Nolan, W.B. Forearm compartment syndrome: Anatomical analysis of surgical approaches to the deep space. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 114, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelberman, R.H.; Zakaib, G.S.; Mubarak, S.J.; Hargens, A.R.; Akeson, W.H. Decompression of forearm compartment syndromes. Clin. Orthop. 1978, 134, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLee, J.C.; Stiehl, J.B. Open tibia fracture with compartment syndrome. Clin. Orthop. 1981, 160, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blick, S.S.; Brumback, R.J.; Poka, A.; Burgess, A.R.; Ebraheim, N.A. Compartment syndrome in open tibial fractures. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1986, 68, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischenko, G.J.; Goodman, S.B. Compartment syndrome after intramedullary nailing of the tibia. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1990, 72, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskey, T.; Hardcastle, J.; O’Toole, R.V. Are Certain Fractures at Increased Risk for Compartment Syndrome After Civilian Ballistic Injury? J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2011, 71, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyani, B.S.; Fisher, B.E.; Roberts, C.S.; Giannoudis, P.V. Compartment Syndrome of the Forearm: A Systematic Review. J. Hand Surg. 2011, 36, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grottkau, B.E.; Epps, H.R.; Di Scala, C. Compartment syndrome in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2005, 40, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, M.M.; Gaston, P.; Court-Brown, C.M. Acute compartment syndrome: Who is at risk? J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2000, 82, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.S.; Kadiyala, R.K.; Waters, P.M. Acute compartment syndrome in children: Contemporary diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2001, 21, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojike, N.I.; Alla, S.R.; Battista, C.T.; Roberts, C.S. A single volar incision fasciotomy will decompress all three forearm compartments: A cadaver study. Injury 2012, 43, 1949–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grechenig, C.; Valsamis, E.M.; Koutp, A.; Hohenberger, G.; di Vora, T.; Grechenig, P. Dual-incision minimally invasive fasciotomy of the anterior and peroneal compartments for chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeKeyser, G.; Bunzel, E.; O’Neill, D.; Nork, S.; Haller, J.; Barei, D. Single-Incision Fasciotomy Decreases Infection Risk Compared with Dual-Incision Fasciotomy in Treatment of Tibial Plateau Fractures with Acute Compartment Syndrome. J. Orthop. Trauma 2023, 37, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Bible, J.E.; Mir, H.R. Single and Dual-Incision Fasciotomy of the Lower Leg. JBJS Essent. Surg. Tech. 2015, 5, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).