Abstract

Lyophilization (freeze-drying) has become a cornerstone pharmaceutical technology for stabilizing biopharmaceuticals, overcoming the inherent instability of biologics, vaccines, and complex drug formulations in aqueous environments. The appropriate literature for this review was identified through a structured search of several databases (such as PubMed, Scopus) covering publications from late 1990s till date, with inclusion limited to peer-reviewed studies on lyophilization processes, formulation development, and process analytical technologies. This succinct review examines both fundamental principles and cutting-edge advancements in lyophilization technology, with particular emphasis on Quality by Design (QbD) frameworks for optimizing formulation development and manufacturing processes. The work systematically analyzes the critical three-stage lyophilization cycle—freezing, primary drying, and secondary drying—while detailing how key parameters (shelf temperature, chamber pressure, annealing) influence critical quality attributes (CQAs) including cake morphology, residual moisture content, and reconstitution behavior. Special attention is given to formulation strategies employing synthetic surfactants, cryoprotectants, and stabilizers for complex delivery systems such as liposomes, nanoparticles, and biologics. The review highlights transformative technological innovations, including artificial intelligence (AI)-driven cycle optimization, digital twin simulations, and automated visual inspection systems, which are revolutionizing process control and quality assurance. Practical case studies demonstrate successful applications across diverse therapeutic categories, from small molecules to monoclonal antibodies and vaccines, showcasing improved stability profiles and manufacturing efficiency. Finally, the discussion addresses current regulatory expectations (FDA/ICH) and compliance considerations, particularly regarding cGMP implementation and the evolving landscape of AI/ML (machine learning) validation in pharmaceutical manufacturing. By integrating QbD-driven process design with AI-enabled modeling, process analytical technology (PAT) implementation, and regulatory alignment, this review provides both a strategic roadmap and practical insights for advancing lyophilized drug product development to meet contemporary challenges in biopharmaceutical stabilization and global distribution. Despite several publications addressing individual aspects of lyophilization, there is currently no comprehensive synthesis that integrates formulation science, QbD principles, and emerging digital technologies such as AI/ML and digital twins within a unified framework for process optimization. Future work should integrate advanced technologies, AI/ML standardization, and global access initiatives within a QbD framework to enable next-generation lyophilized products with improved stability and patient focus.

1. Introduction

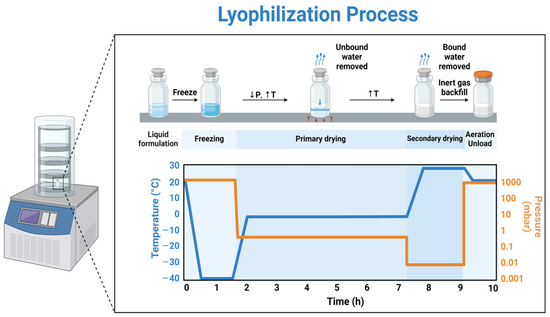

Many biopharmaceutical entities are unstable in aqueous solutions over extended periods. The presence of water, whether as a solvent or cosolvent, can lead to degradation through hydrolysis or other chemical reactions due to increased molecular mobility in the liquid state. Elevated temperatures can further accelerate these degradation processes. Lyophilization (Figure 1), which involves low-temperature vacuum drying, offers a safe and efficient method to remove water and transform the substance into a solid form, thereby enhancing long-term stability [1]. This stabilization process is a method of choice for heat-sensitive medications [2] and starts with the freezing phase to obtain a frozen mass [3], followed by sublimation (primary drying) and desorption (secondary drying) to obtain reduced solvent levels. Solvent quantities are reduced to such a level that the final product does not support any chemical reaction or biological growth [4,5].

Figure 1.

Schematic of the three processes that occur during lyophilization [6]. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

The evolution of lyophilization, originally developed during World War II to preserve heat-sensitive biological materials such as plasma and vaccines, has since become a cornerstone technology in modern biopharmaceutical manufacturing. This review builds on that historical foundation to explore its contemporary relevance in the stabilization of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), recombinant protein therapeutics, and vaccines—the three primary classes of biologics that dominate current clinical and commercial pipelines. These biologics are particularly susceptible to degradation during storage and transportation, making lyophilization a critical step for maintaining structural integrity and therapeutic efficacy. Contemporary drugs often exhibit poor solubility and necessitate their development into complex dosage forms such as liposomes and micro/nanoparticles. Due to their inherent instability, these dosage forms are susceptible to tendencies like agglomeration and sedimentation; however, they can be effectively stabilized using freeze drying [7]. The composition of the material—whether it is an intermediate, active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), or final product governs the formulation behavior and, in turn, defines the processing conditions required for successful handling. These processing conditions directly influence the parameters of the lyophilization cycle and, consequently, the equipment design. Shelf-temperature, chamber pressure and time are the key parameters that critically influence the product quality [1].

Lyophilization has progressed from a basic preservation method to a fundamental process in modern pharmaceutical manufacturing, enabling the long-term stability of biologics, vaccines, and other moisture-sensitive therapeutics. The application of Quality by Design (QbD) principles has shifted the process from empirical trial-and-error to a science-based, systematically controlled approach. Pharmaceutical product quality is defined as the drug product that meets pre-established pharmaceutical attributes or regulatory specifications. A quality product consistently delivers the label claims and is characterized by lack of contamination [8]. Pharmaceutical QbD focuses on identifying CQAs and key variables, enabling optimization of both the final product and the development process [9]. Key components of QbD include defining the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), conducting risk assessments, designing and understanding the product and process to identify Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs), and implementing a control strategy to consistently ensure high product quality [10,11,12]. This concise review presents a modern, integrative framework for the lyophilization process that combines Quality by Design (QbD) principles with emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to enhance process efficiency and product quality. It uniquely contributes to the field by demonstrating how data-driven, risk-based approaches supported by AI can optimize predictive modeling, process control, and decision-making. Furthermore, the inclusion of novel excipients—such as advanced cryo/lyoprotectants, synthetic surfactants, and tonicity agents—improves product stability, reconstitution performance, and overall shelf-life. Together, this multidisciplinary strategy bridges formulation science and digital innovation, offering a next-generation roadmap for developing robust, efficient, and patient-centered biopharmaceuticals.

2. QbD-Driven Development and Performance of Lyophilized Products

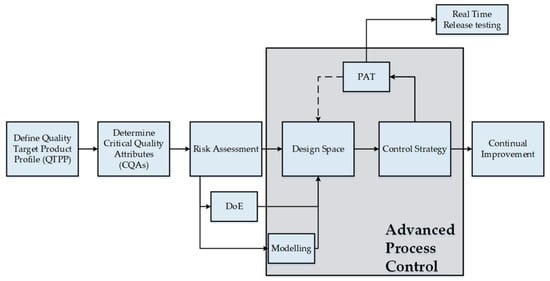

QbD has evolved through the introduction of The International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines, including ICH Q8 (R2) on Pharmaceutical Development, ICH Q9 on Quality Risk Management, and ICH Q10 on the Pharmaceutical Quality System. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began implementing the Quality by Design (QbD) approach in lyophilization technology, promoting robust testing of the final lyophilized product as a standard practice [13]. Pharmaceutical QbD represents a structured development approach that begins with clear defined objectives and focuses on deep product and process understanding, along with scientifically grounded risk management [14,15]. This methodology identifies quality attributes from the end-user’s perspective and translates them into critical characteristics of the drug product. It establishes connections between formulation and manufacturing parameters such as CMAs, CPPs, and CQAs to ensure consistent production of high-quality pharmaceuticals (Figure 2) [16]. Despite its many benefits, the adoption of QbD varies throughout the pharmaceutical industry due to differing levels of comprehension, leading to challenges in its implementation. The development of lyophilized products involves intricate interactions among numerous formulation and process variables and understanding their impact is essential to ensure product quality [17,18]. Optimizing these variables is also vital for consistent manufacturing outcomes. Proactive risk identification and mitigation are central to the QbD approach, while inaccurate risk assessments can result in unforeseen failures and compromised product quality. A solid grasp of QbD principles is therefore crucial in minimizing quality-related issues during development. The key elements of QbD are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Figure 2.

QbD process development workflow [15]. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

2.1. QTPP Identification and Risk Assessment Analysis

The QTPP for lyophilized dosage forms serves as a forward-looking summary of the desired CQAs expected in the final product [19,20]. These may include attributes such as the cake appearance, uniformity of dosage units, water content, reconstitution time, appearance, pH, color and clarity of the reconstituted solution, assay and related substances [21,22,23]. Table 1 illustrates common excipients used in parenteral lyophilized formulations and their impact on product quality. Within the QbD framework, these quality attributes can be systematically controlled and optimized to achieve the intended product quality. Variations in raw material sources and proposed manufacturing processes are recognized as risk factors that may impact the CQAs, potentially leading to product failure [24,25]. To address this, it is essential to identify the likelihood and potential severity of these risk factors. This enables the development of targeted action plans focused on CMAs and CPPs to mitigate these risks [26]. Table 2 and Table 3 present an overview of possible risk factors and the relevant CQAs and their justification, respectively. High risk suggests that risk is unacceptable and further investigation is needed, while medium risk suggests that risk is acceptable and further investigation may be needed to lower the risk. Low risk indicates that the risk is broadly acceptable.

Table 1.

Common excipients used in parenteral lyophilized formulations.

Table 2.

Risk assessment of formulation factors and process variables.

Table 3.

Justification for risk assessment of formulation factors and process variables.

2.2. Overview of Lyophilization Process: Process Control Parameters and Critical Temperatures

Typical lyophilization process consists of three stages: freezing stage (with optional pre-freezing and annealing stages), primary drying (sublimation) stage and secondary drying (desorption) stage [27,28,29,30,31]. The size and structure of the ice crystals is influenced by freezing initiation and therefore pre-freezing the bulk solution may be necessary before the main freezing step. Usually, the shelf is set to 2–8 °C before vial loading. This pre-freezing step lowers the thermal degradation of molecular entities that are unstable at ambient temperature. Additionally, it reduces vial to vial freezing heterogeneity [32,33]. Alteration of water to ice during the freezing phase separates the solvent from the solutes thus creating a concentrated multi-phase system [34]. To achieve complete solidification, the formulation must be frozen to a lower temperature [4,23]. The freezing step is usually completed in a few hours; however, it largely depends on the fill volume. Freezing of the bulk solution is influenced by fill depth and fill volume should not exceed 50% of the vial capacity. High fill depth results in irregular formation of the ice crystals and affects the product’s resistance to vapor flow. Including an annealing step during the freezing phase can reduce product resistance by promoting the growth of larger ice crystals in the frozen layer [35,36,37]. Large crystals result in larger pores leading to a tortuous path for vapor flow. The annealing step consists of raising the product temperature by 10–20 °C above its Tg (glass transition temperature), while remaining safely below the Teu (eutectic temperature) of any crystalline bulking agents. This temperature is maintained for several hours to allow structural changes. Annealing is typically performed after the initial freezing phase, once the shelf temperature aligns with the product temperature [38]. After annealing, the shelf temperature is reduced back to the final set freezing point.

Primary drying (sublimation) is the most time- and energy-intensive phase of the freeze-drying process. During this stage, water is removed from the frozen product as sublimation occurs under vacuum conditions within the freeze-drying chamber. Primary drying temperature is maintained at 5–7 °C below the Tc (collapse temperature) to prevent melting of the frozen mass [39,40]. The shelf temperature is gradually increased in steps, allowing heat to transfer from the shelf to the product. This heat drives the sublimation of ice within the vials. The resulting water vapor (mass transfer) then moves to the condenser, where it refreezes into ice. During primary drying, the chamber pressure should be set to about 10–30% of the ice vapor pressure corresponding to the target product temperature. For instance, at −5 °C, the vapor pressure of ice is approximately 2765 mTorr (368.63 Pa). Therefore, maintaining a chamber pressure between 50 and 200 mTorr (6.66 to 26.66 Pa) is generally sufficient to ensure efficient sublimation. Insufficient primary drying time can lead to cake melting, elevated moisture content, and eventual product collapse. Therefore, accurately determining the duration needed to reach the target product temperature is essential. It is also recommended to extend drying by 2–3 h after this point to ensure uniformity across vials [33].

Secondary drying, also known as desorption, is the last step of the lyophilization cycle. Some water remains unfrozen during the freezing phase and becomes trapped within the solute matrix as non-freezing water. The primary goal of secondary drying is to lower the residual moisture content to below 1%, ensuring the long-term stability of the lyophilized cake [41]. Temperature and duration are critical in secondary drying, as they directly influence the final moisture content of the product. Depending on the drug’s thermal stability, secondary drying temperatures typically range from 15 °C to 45 °C. Higher temperatures accelerate moisture desorption and reduce drying time, while heat-sensitive products are generally dried at temperatures below 25 °C [33,40].

2.3. Critical Drug Product Attributes

Physical (cake appearance, reconstitution time) and chemical (residual moisture, assay and related substances) quality attributes of lyophilized product are critical to ensure its safety and efficacy. Microbial quality attributes such as particulate matter, sterility and bacterial endotoxin can be controlled by the aseptic manufacturing process [33].

2.3.1. Cake Appearance

Following lyophilization, drug products are visually inspected for cake appearance, extraneous particulate matter and minor, major and critical defects. An ideal lyophilized cake should be elegant, uniform and mechanically strong to withstand handling and distribution. Differences in the lyophilized cake’s appearance may include partial or complete collapse, shrinkage, melt-back, and cracking. The impact of these variations on the product quality should be assessed at batch release and during stability. This is because there are no pre-established criteria for acceptance or rejection of a drug product based on cake alterations [42,43,44]. The FDA’s guidance document Inspections of Lyophilization of Parenterals (7/93) provides a summary of the limited information regarding lyophilized cake appearance.

2.3.2. Reconstitution

Lyophilized parenteral products require reconstitution before administration. The reconstitution time is defined as the time taken for the solid content to completely dissolve in the solution after manual agitation (shaking or swirling) of the vial. It is generally determined by visual observation [45]. Reconstitution time is influenced by formulation (e.g., powder porosity, surface area, gel formation, wettability, foaming), diluent (type and volume), and CCS (e.g. headspace of glass vial) factors [46,47]. In addition to reconstitution time, key properties of the reconstituted solution such as appearance, pH, color and clarity can be objectively evaluated using IV inspection box, pH meter, UV/Colorimeter and turbidimetry/image analysis, respectively. These properties aid in establishment of the shelf life and safety of the end user prior to administration.

2.3.3. Assay and Impurities

The Lyophilization process may cause a loss in potency of the API by inducing degradation of the final product. Differences in fill volume, and drying conditions influence the potency of the drug product. Weight variation and content uniformity tests are essential to ensure dose accuracy. Weight variation is a physical check to determine filling and processing consistency, whereas content uniformity is a chemical test to determine the exact amount of the active ingredient. Reconstituting the entire contents of the vial and performing the assay will confirm the product’s label claim. Assay determination must be performed on the vial with the known weight of the sample. The primary source of hydrolysis degradation is from elastomeric stoppers containing residual moisture. The specifications for degradation impurities are set based on the maximum daily dose of the drug product as mentioned in ICH Q3B [33].

2.3.4. Moisture Content

Primary factors affecting moisture content of the lyophilized drug products are formulation components, container closure system and secondary drying conditions (time and temperature). The presence of a high level of moisture leads to drug product degradation thus leading to physical and chemical instability. Residual moisture in the elastomeric stoppers may ingress into the vial resulting in the moisture uptake by the cake. Drying the vials for an extended period prior to their usage may help in the reduction in the residual moisture levels. Sampling finished product vials from various locations on the shelf provides insight into batch-to-batch consistency of moisture content [48,49].

3. Technology-Driven Advances in Pharmaceutical Lyophilization

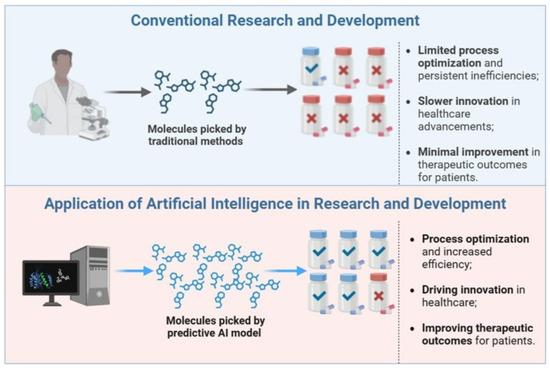

Artificial intelligence is reshaping pharmaceutical formulation development. By optimizing and expediting the design, testing, and manufacturing of these formulations, AI offers significant advantages, including greater efficiency, enhanced accuracy, and the potential to enable personalized medicine [50]. Machine learning models can help optimize manufacturing processes by identifying optimal parameters such as temperature and pressure. Using AI in this way can enhance efficiency and reduce batch-to-batch variability [51]. AI can help predict the stability of formulations under different storage conditions, such as varying temperature and humidity (Figure 3). This enables the design of more stable products, ensuring the drug’s potency and efficacy is maintained throughout its shelf life [52]. Before conducting physical tests, AI can be used to virtually screen excipients, drug compounds, and formulation strategies.

Figure 3.

Applications of AI in Pharmaceutical Innovation [53]. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

This approach reduces the time and cost of laboratory experiments and helps identify the most promising candidates for further development [54,55]. Table 4 provides a concise comparison between traditional and QbD/AI-driven approaches.

Table 4.

Traditional vs. QbD/AI-Driven Lyophilization.

Developing a freeze-drying cycle can take weeks or months due to product complexity, team experience, and resource demands. Traditional methods rely on labor-intensive trial runs and repeated adjustments. Combining QbD with a digital twin framework can greatly speed this up by using predictive modeling based on scientific principles. In one study, a digital twin optimized primary drying conditions by simulating key parameters like critical temperature (Tc), heat transfer coefficient (Kv), sublimation flux (Jmax), and dry layer resistance (Rp). Controlled nucleation improved reproducibility, while simulations ensured product temperatures stayed below Tc. This approach reduced optimization to 14 days using only 540 mL of solution, and to five days for later batches, delivering faster, safer, and more cost-effective lyophilization with up to 300% productivity gains and 60–75% cost savings [56].

Because visual inspection is the industry standard, frequent ‘fogging’ on vials can lead to inaccurate defect detection. Fogging the white haze seen on glass above the product cake after lyophilization is generally considered cosmetic, not critical. However, since fogging cannot be fully eliminated, inspection methods must reliably distinguish it from true product defects. Automating this process is challenging because of vial ‘fogging’ and the limited availability of defective samples to train decision models. Calvin Tsay and Zheng Li applied deep neural networks and computer vision to automate the classification of lyophilized product vials. The approach used shared convolutional layers to process multiple images of each vial taken at different rotations and explored transfer learning to help address the limited availability of defective samples in industrial settings. This method was tested on a real-world industrial product as a case study. Results showed that 85–90% of defects were detected from a single camera angle, highlighting the promise of multi-input neural networks for lyophilized vial inspection. Additionally, the findings indicate that transfer learning improves model generalization, even when using training data from unrelated tasks [57]. Applying artificial intelligence specifically computer vision—to high-resolution images of each freeze-dried product can deliver both quantitative and qualitative improvements over manual visual inspection. In a study, continuously freeze-dried samples were prepared to mimic a real-world pharmaceutical product, with manually added particles ranging from 50 μm to 1 mm. These samples were imaged using a custom setup to create a dataset for training multiple object detection models. The You Only Look Once version 7 (YOLOv7) model significantly outperformed human inspection, achieving a particle detection precision of up to 88.9% with a controlled recall of 81.2%, while detecting most objects in under one second per vial [58]. The topology and surface features of lyophilizates play a key role in the stability and ease of reconstitution of freeze-dried pharmaceuticals. As a result, visual quality control is essential. However, this process is time-consuming, labor-intensive, costly, and susceptible to human error. A study examined a fully automated and non-destructive approach for inspection of freeze-dried pharmaceuticals [59].

Drăgoi et al. developed a detailed phenomenological model to generate training data for the neural network. A self-adaptive differential evolution method, combined with a back-propagation algorithm, optimized the network’s structure and parameters to model the freeze-drying process. Using real-time measurements, the network estimated future product temperature and dried cake thickness under given operating conditions (shelf temperature and chamber pressure). From cake thickness, residual ice and sublimation flux were calculated. The model also predicted the duration of primary drying and maximum product temperature, helping determine if process adjustments were needed to avoid exceeding temperature limits. Even when tested under different heat and mass transfer conditions than the training data, the network provided accurate, reliable predictions [60].

An experimental study applied neural network-based models integrated with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to predict temperature distribution during the freeze-drying of biopharmaceuticals. Among the models evaluated—Single-Layer Perceptron (SLP), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), and Deep Neural Network (DNN)—the MLP exhibited the highest predictive accuracy (R2 ≈ 0.997), demonstrating superior performance in capturing spatial temperature variations. Optimization using the Fireworks Algorithm (FWA) further enhanced model precision, underscoring the potential of AI-driven modeling for accurate temperature prediction and process optimization in pharmaceutical freeze-drying [61]. Accurate temperature prediction in pharmaceutical freeze-drying is challenging due to nonlinear spatial–temperature relationships. This study compares Cheetah Optimizer (CO)-enhanced machine learning models—Support Vector Regression (SVR), Poisson Regression (POR), and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)—for temperature prediction based on spatial coordinates. The CO-SVR model achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.953, MSE = 9.893, MAE = 2.549), outperforming CO-ANFIS and CO-POR. These findings demonstrate the superior predictive power of CO-SVR and the potential of CO-optimized ML models for precise temperature estimation in freeze-drying processes [62].

Drug–excipient compatibility assessment is a critical component of pre-formulation studies, aimed at identifying potential physicochemical or chemical interactions that could affect the stability, efficacy, or processability of the formulation during lyophilization. A machine learning-based approach was presented in a study using Mol2vec and 2D molecular descriptors with a stacking technique to enhance prediction accuracy. The model achieved high performance (accuracy = 0.98, precision = 0.87, recall = 0.88, AUC = 0.93, MCC = 0.86) and outperformed the DE-INTERACT model by correctly identifying 10 of 12 incompatibility cases versus 3 of 12. The trained model is accessible via a user-friendly web platform, allowing compatibility prediction from compound names, PubChem CIDs, or SMILES strings. Continuous model refinement remains essential for broader practical application [63].

Artificial intelligence holds immense promise for revolutionizing lyophilization in pharmaceutical manufacturing, yet several critical challenges must be overcome to realize its full potential. The path to adoption faces hurdles, including data limitations where sparse, fragmented, and proprietary datasets constrain model generalizability, along with stringent requirements for GMP-compliant validation to ensure reproducibility, reliability, and regulatory compliance. Success will depend on coordinated efforts between drug manufacturers, AI developers, and regulatory bodies to establish standardized validation protocols and lifecycle management frameworks that balance innovation with quality assurance. When effectively implemented, AI transforms lyophilization through predictive modeling that accelerates cycle development, adaptive process control for real-time optimization, and resource-efficient digital twin simulations [64]. These advancements dramatically reduce development timelines and costs while enhancing product consistency particularly crucial for sensitive biologics like vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and gene therapies where precision lyophilization is paramount [65]. Capitalizing on this opportunity requires a concerted industry focus on three fronts: fostering deeper collaboration across scientific, technical, and regulatory disciplines; building robust digital infrastructure to support AI integration; and maintaining proactive dialog with regulators to align evolving standards with technological progress. By addressing these priorities, the pharmaceutical industry can unlock a new era of intelligent lyophilization, delivering faster, more cost-effective, and higher-quality manufacturing for next-generation therapeutics.

4. Scope, Industrial Relevance and Pharmaceutical Applications

4.1. Conventional Small Molecules

Lyophilization has long been used to produce stable, elegant injectable formulations. Antimicrobial agents inhibit/kill the infecting microorganism(s) without significantly affecting the host. The principle of selective microbial toxicity relies on targeting a microbial structure (such as the cell wall) or a metabolic pathway (such as folate synthesis) absent in the host. A project was designed to develop a lyophilized combination of a β-lactam antibiotic and β-lactamase inhibitor with reduced cycle time and improved stability, making the product more economical. Excipients in a lyophilized formulation are selected based on specific formulation needs to achieve a simple, stable, and elegant product. Three bulking agents (mannitol, lactose, dextrose) were tested at various concentrations. Six formulations were prepared and lyophilized using three different cycles. Among these, formulation F2 with 5% mannitol and lyophilization cycle 3 gave the best results, showing good cake structure, faster processing, and compliance with USP limits during three months of accelerated stability testing. Overall, F2 with 5% mannitol was identified as the optimal formulation for a stable injectable product with enhanced cake characteristics and shorter lyophilization time [66].

Cyclophosphamide, an API, is available in monohydrate form and valued for its excellent stability. Preserving this monohydrate form after lyophilization is crucial to ensure product stability. A study focused on optimizing key lyophilization parameters to develop an effective and robust freeze-drying cycle using a QbD framework-primary drying temperature, time and vacuum were examined. Results confirmed the existence of monohydrate form as verified by moisture analysis and X-ray diffraction (XRD) [67].

4.2. Liposomes

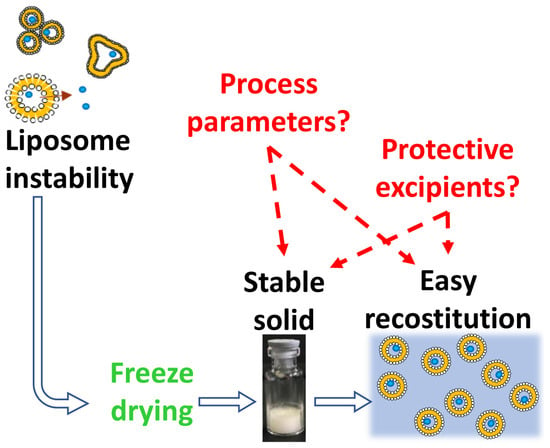

Liposomes are highly versatile drug delivery systems that use their unique structural properties to improve therapeutic efficacy. They are spherical vesicles composed of one or more lipid bilayers, enabling the encapsulation of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [68,69,70]. Despite their advantages, these complex systems often suffer from physico-chemical instabilities that can limit shelf life. Key stability concerns include liposome aggregation, phospholipid oxidation, poor re-dispersibility, and drug leakage. Lyophilization (freeze-drying) is commonly employed to address these issues, although maintaining liposomal integrity during the process remains a major challenge [71,72]. A lyophilized liposomal formulation (Figure 4) containing a peptidomimetic–doxorubicin conjugate was developed to achieve targeted delivery to HER2-positive cancer cells. This pH-sensitive formulation demonstrated greater efficacy than the free drug and maintained long-term stability at 4 °C [73].

Figure 4.

Freeze-drying of liposome dispersions [74]. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Multilamellar liposomes containing 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) were prepared using a modified lipid film hydration method and lyophilized with or without saccharose as a cryoprotectant. The impact of lyophilization on liposome stability was assessed by comparing vesicle size, encapsulation efficiency, and drug release before and after freeze-drying and rehydration. Lyophilization without a cryoprotectant led to increased particle size and significant drug leakage, whereas adding saccharose stabilized the lipid bilayers, reduced permeability, and retained about 80% of 5-FU. With saccharose, freeze-drying did not affect particle size. The rehydrated liposomes exhibited biphasic drug release following Higuchi’s square root model: an initial burst release from leaked drug, followed by sustained zero-order release [75].

4.3. Synthetic Surfactants

Synthetic surfactants are amphiphilic molecules extensively employed in lyophilized pharmaceutical formulations to improve stability, prevent aggregation, and enhance reconstitution efficiency [76]. Their primary function lies in reducing interfacial tension at solid-liquid and liquid-vapor interfaces, thereby mitigating stress-induced degradation of labile biomolecules such as proteins, liposomes, and nanoparticles throughout the freeze-drying process [77]. Commonly used synthetic surfactants include polysorbates (e.g., polysorbate 20 and 80), poloxamers (e.g., Pluronic F68), and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based agents. During freezing and primary drying, proteins are particularly vulnerable to interface-induced denaturation and aggregation. Surfactants act by preferentially adsorbing to hydrophobic interfaces, effectively shielding proteins from shear forces and ice crystal-induced stress [78]. For instance, polysorbate 20 has been shown to reduce monoclonal antibody (mAb) aggregation by competitively occupying interfacial sites and stabilizing protein conformation [79]. The effect of hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding and Van der Waals’ forces between poloxamer 188 and tween 80 with methotrexate to improve stability and solubility were studied using Plackett–Burman and Central Composite designs [80]. In liposomal systems, nonionic surfactants such as Tween 80 help maintain bilayer integrity by preventing vesicle fusion and minimizing phase transition disturbances. Nanoparticles also benefit from surfactant-mediated stabilization, with agents like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) providing electrostatic or steric hindrance to aggregation [81].

In addition to stabilizing complex biological structures, synthetic surfactants improve the wettability of lyophilized cakes, thereby accelerating reconstitution kinetics, a key parameter for clinical usability, particularly in vaccine and emergency formulations [82]. Poloxamers, owing to their block copolymer architecture, exhibit high thermal stability and minimal oxidative degradation, making them advantageous for long-term storage under fluctuating environmental conditions. Despite their benefits, surfactants must be carefully optimized within a QbD framework. They are recognized as CMAs due to their significant influence on CQAs such as aggregation propensity, residual moisture content, and cake morphology. Surfactant concentration may also influence thermal characteristics of the formulation matrix, including collapse temperature (Tc) and glass transition temperature (Tg), thereby affecting product robustness [83]. Halikala et al. investigated the influence of surfactants on the crystallization behavior of mannitol. They found that increasing the concentration of polysorbate 80 led to enhanced crystallinity of mannitol, and at concentrations of 0.01% or higher, a greater proportion of δ-mannitol was produced [84]. Risk assessment tools such as Ishikawa diagrams and Design of Experiments (DOE) studies are instrumental in balancing efficacy and safety [83].

Emerging technologies are pushing the frontiers of surfactant design and application. Machine learning models are being developed to predict surfactant-excipient interactions and degradation pathways, reducing reliance on empirical screening. Furthermore, novel biodegradable and bioengineered surfactants such as rhamnolipids are under exploration to address concerns regarding toxicity and environmental impact. Table 5 describes the key advantages of bioengineered surfactants over synthetic surfactants. While polysorbates remain the industry standard, they are not without challenges. Their susceptibility to hydrolytic and oxidative degradation can lead to the formation of free fatty acids thus producing visible and subvisible particulates that are potentially immunogenic species. Mitigation strategies include the addition of antioxidants like ascorbic acid or substitution with more stable alternatives such as sucrose esters. As the pharmaceutical landscape shifts toward complex biologics and personalized medicine, the role of surfactants must evolve to accommodate diverse formulation needs and stringent regulatory expectations. Tools such as cryo-TEM and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) will be increasingly vital in mechanistic understanding and real-time monitoring [85].

Table 5.

Comparison of synthetic vs. bioengineered surfactants.

4.4. Nanoparticles

In recent decades, nanoparticles have attracted significant attention in medical sciences [86,87], particularly in the areas of imaging [88,89], sensing [90,91], gene delivery [92,93], and drug delivery [94,95]. The development of nanoparticle-based drug formulations has created new opportunities to address challenging diseases [96]. Nanoparticles typically range from 100 to 500 nm in size. By tailoring their size, surface properties, and materials, they can be engineered into smart systems that carry both therapeutic and imaging agents while exhibiting stealth characteristics. Further, these systems can deliver drug to specific tissues and provide controlled release therapy [97,98]. Neurotensin (NTS)-polyplex is a nanoparticle system for targeted gene delivery with significant potential for treating Parkinson’s disease and various cancers. However, its instability in aqueous suspension limits its clinical application. To address this, a clinical-grade formulation and lyophilization process for NTS-polyplex nanoparticles was developed. Reconstituted samples were compared with fresh preparations using transmission electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering, electrophoretic mobility, circular dichroism, and in vitro and in vivo transfection assays. The new formulation provided lyoprotection and maintained nanoparticle stability. TEM and SEC-HPLC with a radioactive tag confirmed that interaction with fetal bovine or human serum did not affect their biophysical properties. Moreover, the formulation and freeze-drying process preserved functional nanoparticles for at least six months at 25 °C and 60% relative humidity. These findings offer a pharmaceutical strategy for the formulation and long-term storage of NTS-polyplex nanoparticles, with potential application to other polyplex systems [99].

Freeze-drying often causes destruction and aggregation of polymeric nanoparticles. The integrity of doxorubicin-loaded polymeric nanoparticles (DOX-NPs) made from mPEG-PLGA-PGlu was first evaluated without stabilizers using DSC, microscopy, and FT-IR. Although the nanoparticles retained their nanostructure due to the copolymer’s long hydrophobic block, severe aggregation still occurred. Various lyoprotectants were then screened to prevent this. A low concentration of hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD, 1% w/v) effectively stabilized DOX-NPs, maintaining particle size and PDI after reconstitution by forming an inclusion complex at the surface. In vivo, the reconstituted DOX-NPs showed AUC0–t, AUC0–∞, and t1/2 values 2.65-, 3.13-, and 8.68-fold higher than free doxorubicin. Compared to free DOX, they reduced drug levels in major organs and doubled tumor accumulation at 8 h post-injection in tumor-bearing mice. Enzyme analysis confirmed no organ toxicity for DOX-NPs, while free DOX showed clear heart toxicity at 10 mg/kg. Overall, the lyophilized DOX-NPs demonstrated strong potential for clinical use [100].

4.5. Biologics/Vaccines

Lyophilization has become essential in the biopharmaceutical industry as more biological entities are developed as therapeutics. For biologics that are unstable in aqueous solutions, freeze-drying remains the most common and effective strategy for enhancing long-term stability [101]. The QbD approach to evaluate multiple variables and their interactions affecting the quality of a challenging model murine IgG3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was utilized to develop an optimized formulation with a defined quality target product profile. This antibody was selected due to its tendency to precipitate, making it a good test case for difficult formulations. Initial experiments excluded incompatible buffers. A fractional factorial design screened the effects of buffer type, pH, and excipients (sucrose, NaCl, lactic acid, Polysorbate 20) on key attributes such as glass transition temperature (Tg), concentration, aggregation, unfolding temperature (Tm), and particle size after reconstitution. A Box–Behnken design further explored main, interaction, and quadratic effects. Pareto analysis identified pH, NaCl, and Polysorbate 20 as the most influential factors. An optimal design space was established and verified experimentally, indicating that high pH (8), moderate NaCl (50 mM), and low Polysorbate 20 (0.008 mM) levels produced the best formulation. Analytical tests confirmed protein integrity and minimal aggregation post-lyophilization. Overall, this experimental design approach successfully defined optimal excipient concentrations and pH for this difficult mAb formulation [102].

Development studies were carried out to design a pharmaceutical composition that stabilizes a parenteral rhEGF formulation as a lyophilized dosage form. Both unannealed and annealed drying protocols were tested during excipient screening. Freeze-dry microscopy guided the selection of excipients, formulations, and freeze-drying parameters. Excipients were evaluated for their impact on freeze-drying recovery and dried product stability at 50 °C, using analytical methods to assess chemical stability, protein conformation, and bioactivity. Sucrose and trehalose provided the best stability during freeze-drying, while dextran, sucrose, trehalose, or raffinose best preserved stability during storage at 50 °C. A formulation combining sucrose and dextran effectively prevented protein degradation during both drying and delivery. The degradation rate, measured by RP-HPLC, was reduced by 100-fold at 37 °C and 70-fold at 50 °C compared to the aqueous form. These results demonstrate that the freeze-dried formulation offers a robust solution for stabilizing rhEGF [103].

Poliomyelitis is a highly infectious disease, affecting young children. The disease is caused by any one of three serotypes of poliovirus (type 1, type 2 or type 3) and does not have any specific treatment. However, the occurrence can be prevented through vaccination. A study was conducted to develop a dried inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) using D-optimal design with 22 formulations to determine the effect of commonly used stabilizers. A 24 full factorial design was used for screening of excipients and the central composite circumscribed design was used for formulation optimization. The results showed the potential of development of a lyophilized vaccine with minimal potency loss and the possibility of eliminating the need of a cold chain [104]. Recent advances have demonstrated that circRNA vaccines maintain their immunogenic potency after lyophilization and storage at standard refrigeration temperatures, helping to overcome cold-chain challenges that limit the global distribution of traditional mRNA vaccines [105,106].

5. Scientific and Regulatory Considerations (FDA Perspective)

The development of a lyophilized parenteral product must align with FDA requirements for sterile drug manufacturing, as described in the Guidance for Industry: Sterile Drug Products Produced by Aseptic Processing—Current Good Manufacturing Practice [107]. The CQAs such as residual moisture, cake appearance, and reconstitution time must be defined and controlled through scientifically justified process parameters, guided by thermal properties like the glass transition temperature (Tg) and collapse temperature (Tc). Consistent with FDA’s adoption of ICH Q8(R2) (Pharmaceutical Development), a QbD framework is applied to identify CPPs and establish an appropriate design space. Validation must follow FDA’s Process Validation: General Principles and Practices [108]. Container-closure integrity must meet standards outlined in the Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics guidance [109]. Analytical methods for residual moisture, cake structure, and sterility should comply with USP requirements and FDA method validation principles. Together, these measures ensure that the lyophilized product remains stable, safe, and compliant, supporting robust CMC documentation for INDs (Investigational New Drug), NDAs (New Drug Application), or BLAs (Biologic License Application).

From the FDA perspective, the integration of AI and machine learning (ML) into the development of pharmaceutical products, including lyophilized parenteral dosage forms, must align with existing regulatory principles for safety, quality, and process control. As outlined in FDA discussion papers and the Agency’s evolving AI/ML framework, AI can enhance pharmaceutical development by supporting advanced modeling, predictive cycle design, real-time process monitoring, and QbD applications. However, AI models used to optimize critical steps in lyophilization—such as freeze–thaw behavior, primary drying conditions, and CQAs must be scientifically justified, transparent, and validated in line with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) and established guidelines for process validation and control. The FDA emphasizes that any AI-driven tool or model must produce explainable, reproducible results that can be traced within a robust quality system, ensuring that data integrity and product quality meet regulatory expectations for sterile parenteral products. The FDA’s evolving guidance (Using Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning in the Development of Drug & Biological Products) underscores that any AI-driven decision-making must be transparent and auditable, with robust documentation to demonstrate data integrity, traceability, and reproducibility. For lyophilized products, this means AI/ML must support scientifically justified design spaces and maintain sterility assurance and product quality throughout development, scale-up, commercial manufacturing and shelf-life [106,110].

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This review consolidates current scientific understanding and industrial practices in pharmaceutical lyophilization, emphasizing the integration of Quality by Design (QbD) principles and emerging digital technologies to enhance process robustness and product quality. Our analysis highlights how systematic application of QbD has transformed lyophilization from an empirical operation to a mechanistically guided process, allowing better control of critical process parameters and quality attributes.

Based on the literature evaluated, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and digital twin frameworks are now enabling data-driven process optimization, cycle prediction, and real-time monitoring, offering tangible reductions in development timelines and variability. These technologies, when implemented within a regulatory-aligned QbD framework, are positioned to redefine process control and lifecycle management in lyophilized product manufacturing.

We also observe a growing need for harmonization between technological innovation and regulatory acceptance. Standardization of AI/ML models, validation strategies, and transparent data handling will be essential for broader implementation under cGMP conditions. Furthermore, lyophilization continues to play a pivotal role in global access to biologics and vaccines by improving thermal stability and reducing cold-chain dependency—particularly relevant for resource-limited settings.

In conclusion, lyophilization stands at a pivotal juncture where scientific insight, digital innovation, and regulatory science converge. By advancing stabilization strategies for complex biologics, adopting validated AI-driven models, and promoting globally accessible manufacturing paradigms, the field can evolve toward smarter, more efficient, and patient-centered lyophilized therapeutics.

Future efforts must focus on:

Integration of cutting-edge technologies such as continuous lyophilization, IoT-enabled equipment, and blockchain-based quality tracking.

Advanced Stabilization Strategies: Developing biodegradable surfactants and cryoprotectants for complex biologics.

AI Standardization: Establishing validated AI/ML models for regulatory acceptance.

Global Accessibility: Leveraging lyophilization to overcome cold-chain barriers for vaccines and thermosensitive therapies.

By integrating QbD, AI, and robust regulatory science, the pharmaceutical industry can unlock next-generation lyophilized products that combine stability, efficacy, and patient-centric design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A. and S.A.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A. and S.A.A.R.; writing—review and editing, P.A. and S.A.A.R. Both P.A. and S.A.A.R. contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No primary research result, software, or code has been included, and no new data were generated or analyzed as part of this review. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Costantino, H.R.; Pikal, M.J. Lyophilization of Biopharmaceuticals; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ledet, G.A.; Graves, R.A.; Bostanian, L.A.; Mandal, T.K. Spray-Drying of Biopharmaceuticals. In Lyophilized Biologics and Vaccines: Modality-Based Approaches; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, B.D.; Le, L.; Patapoff, T.W.; Cromwell, M.E.M.; Moore, J.M.R.; Lam, P. Protein Aggregation in Frozen Trehalose Formulations: Effects of Composition, Cooling Rate, and Storage Temperature. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 4170–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, D.; Iqbal, Z. Lyophilization—Process and optimization for pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Drug Regul. Aff. 2018, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidhani, K.A.; Harwalkar, M.; Bhambere, D.; Nirgude, P.S. Lyophilization/Freeze Drying—A Review. World J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 4, 516–543. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; Patel, R.; Wang, B.; Evans-Nguyen, T.; Patel, N.A. Lyophilized Small Extracellular Vesicles (sEVs) Derived from Human Adipose Stem Cells Maintain Efficacy to Promote Healing in Neuronal Injuries. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar, G.; Prashanth, N.; Chaitanya Kumari, B. Fundamentals and Applications of Lyophilization. J. Adv. Pharm. Res. 2011, 2, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, J. The concept of pharmaceutical quality. Am. Pharm. Rev. 2004, 7, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M.T.; Alahmed, T.A.A.; Sami, F. Quality by Design (QbD) Concept for Formulation of Oral Formulations for Tablets. In Introduction to Quality by Design (QbD) From Theory to Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.X.; Amidon, G.; Khan, M.A.; Hoag, S.W.; Polli, J.; Raju, G.K.; Woodcock, J. Understanding pharmaceutical quality by design. AAPS J. 2014, 16, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atre, P.; Rizvi, S.A.A. Advances in Oral Solid Drug Delivery Systems: Quality by Design Approach in Development of Controlled Release Tablets. BioChem 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.K.; Jee, J.P.; Jang, D.J.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, J.E. Quality by Design (QbD) application for the pharmaceutical development process. J. Pharm. Investig. 2022, 52, 649–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Pharmaceutical CGMPs for the 21s Century—A Risk-Based Approach; Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Xu, X.; Khan, M.A.; Burgess, D.J. A quality by design (QbD) case study on liposomes containing hydrophilic API: I. Formulation, processing design and risk assessment. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 419, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juckers, A.; Knerr, P.; Harms, F.; Strube, J. Effect of the Freezing Step on Primary Drying Experiments and Simulation of Lyophilization Processes. Processes 2023, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.X. Pharmaceutical quality by design: Product and process development, understanding, and control. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, D.; Choudhary, N.K. Enhancing Sublingual Tablet-Quality Through Quality-by-Design Principles: Current Trends and Insights. Precis. Med. 2023, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Jagan, B.G.V.S.; Murthy, P.N.; Mahapatra, A.K.; Patra, R.K. Quality by design (QBD): Principles, underlying concepts, and regulatory prospects. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 45, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, D.W. Impact of quality by design on topical product excipient suppliers, part I: A drug manufacturer’s perspective. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 40, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, J.G.; Blanco, M.; González, J.M.; Alcalá, M. Quality by design approach of a pharmaceutical gel manufacturing process, part 1: Determination of the design space. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 4432–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, H. Qbd in developing topical dosage forms. Ely. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S. Quality by design (QBD): A comprehensive understanding of implementation and challenges in pharmaceuticals development. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, H.; Shimanouchi, T.; Kimura, Y. Recent Development of Optimization of Lyophilization Process. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 9502856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.K.; Raw, A.; Lionberger, R.; Yu, L. Generic development of topical dermatologic products: Formulation development, process development, and testing of topical dermatologic products. AAPS J. 2012, 15, 41–52, Erratum in AAPS J. 2013, 17, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, M. Manufacturing Topical Formulations: Scale-up from Lab to Pilot Production. In Handbook of Formulating Dermal Applications; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, D.; Zahel, T.; Thomassen, Y.E.; Herwig, C.; Suarez-Zuluaga, D.A. Quantitative CPP Evaluation from Risk Assessment Using Integrated Process Modeling. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The freeze-drying of foods—The characteristic of the process course and the effect of its parameters on the physical proNoperties of food materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, I.; Gupta, M.N. Freeze-drying of proteins: Some emerging concerns. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2004, 39, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, X. Exergy analysis for a freeze-drying process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S. Freeze drying process: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 3061. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Dash, S.K.; Dhawan, D.; Sahoo, P.K.; Jindal, A.; Gugulothu, D. Freeze-drying revolution: Unleashing the potential of lyophilization in advancing drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 1111–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passot, S.; Tréléa, I.C.; Marin, M.; Galan, M.; Morris, G.J.; Fonseca, F. Effect of controlled ice nucleation on primary drying stage and protein recovery in vials cooled in a modified freeze-dryer. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009, 131, 074511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butreddy, A.; Dudhipala, N.; Janga, K.Y.; Gaddam, R.P. Lyophilization of Small-Molecule Injectables: An Industry Perspective on Formulation Development, Process Optimization, Scale-Up Challenges, and Drug Product Quality Attributes. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franks, F.; Auffret, T. Freeze-Drying of Pharmaceuticals and Biopharmaceuticals; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, S.; Seyferth, S.; Lee, G. Measurement of shrinkage and cracking in lyophilized amorphous cakes. Part I: Final-product assessment. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.C.; Nail, S.L.; Pikal, M.J. Evaluation of manometric temperature measurement, a process analytical technology tool for freeze-drying: Part II measurement of dry-layer resistance. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneid, S.; Gieseler, H. Effect of Concentration, Vial Size, and Fill Depth, on Product Resistance of Sucrose Solution During Freeze-Drying. In Proceedings of the 6th World Meeting on Pharmaceutics, Biopharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Searles, J.A.; Carpenter, J.F.; Randolph, T.W. The ice nucleation temperature determines the primary drying rate of lyophilization for samples frozen on a temperature-controlled shelf. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 90, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Alvarez, M.A.; Acosta, L.L.; Terry, A.M.; Labrada, A. Establishing a Multi-Vial Design Space for the Freeze-Drying Process by Means of Mathematical Modeling of the Primary Drying Stage. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 113, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lale, S.V.; Goyal, M.; Bansal, A.K. Development of lyophilization cycle and effect of excipients on the stability of catalase during lyophilization. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2011, 1, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Pikal, M.J. Design of Freeze-Drying Processes for Pharmaceuticals: Practical Advice. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.M.; Nail, S.L.; Pikal, M.J.; Geidobler, R.; Winter, G.; Hawe, A.; Davagnino, J.; Gupta, S.R. Lyophilized Drug Product Cake Appearance: What Is Acceptable? J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 1706–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiary, R.; Gattu, S.K.; Stewart, J.M.; Patel, S.M. Effect of Freezing on Lyophilization Process Performance and Drug Product Cake Appearance. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, F. Freeze-drying of bioproducts: Putting principles into practice. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1998, 45, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werk, T.; Huwyler, J.; Hafner, M.; Luemkemann, J.; Mahler, H.C. An Impedance-Based Method to Determine Reconstitution Time for Freeze-Dried Pharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 2948–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwale, P.; Amin, A.; Kumar, L.; Bansal, A.K. Variables affecting reconstitution time of dry powder for injection. Pharm. Technol. 2008, 32, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, A.K. Product development issues of powders for injection. Pharm. Technol. 2002, 26, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.F.; Bunnell, R. Moisture matters in lyophilized drug product using an alternate moisture-generation method may provide more accurate data for regulatory submissions. Biopharm Int. 2012, 25, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mirasol, F. Lyophilization presents complex challenges. Biopharm Int. 2020, 33, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huanbutta, K.; Burapapadh, K.; Kraisit, P.; Sriamornsak, P.; Ganokratana, T.; Suwanpitak, K.; Sangnim, T. The Artificial Intelligence-Driven Pharmaceutical Industry: A Paradigm Shift in Drug Discovery, Formulation Development, Manufacturing, Quality Control, and Post-Market Surveillance. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 203, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Nugent, M.; Whitaker, D.; McAfee, M. Machine learning for process monitoring and control of hot-melt extrusion: Current state of the art and future directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, X.; Ouyang, D.; Williams, R.O. Emerging Artificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies Used in the Development of Solid Dosage Forms. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, V.; Santos, B.; Figueiras, A.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F. The potential of artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical innovation: From drug discovery to clinical trials. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, G.K.; Patra, C.N.; Jammula, S.; Rana, R.; Chand, S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Implemented Drug Delivery Systems: A Paradigm Shift in the Pharmaceutical Industry. J. BioX Res. 2024, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Singh, A.; Singhal, R.; Yadav, J.P. Revolutionizing drug discovery: The impact of artificial intelligence on advancements in pharmacology and the pharmaceutical industry. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Behera, M.; Saraf, S.A.; Shukla, R. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Synergies in Drug Discovery: From Computers to Clinics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2024, 30, 2187–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, C.; Li, Z. Automating Visual Inspection of Lyophilized Drug Products with Multi-Input Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–26 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Herve, Q.; Ipek, N.; Verwaeren, J.; De Beer, T. Automated particle inspection of continuously freeze-dried products using computer vision. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 664, 124629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.; Sack, A.; Dümler, J.; Heckel, M.; Wenzel, T.; Siegert, T.; Schuldt-Lieb, S.; Gieseler, H.; Pöschel, T. Automated tomographic assessment of structural defects of freeze-dried pharmaceuticals. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drǎgoi, E.N.; Curteanu, S.; Fissore, D. On the Use of Artificial Neural Networks to Monitor a Pharmaceutical Freeze-Drying Process. Dry. Technol. 2013, 31, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hagbani, T.; Alamoudi, J.A.; Bajaber, M.A.; Alsayed, H.I.; Al-Fanhrawi, H.J. Theoretical investigations on analysis and optimization of freeze drying of pharmaceutical powder using machine learning modeling of temperature distribution. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.; Alqarni, A.A. Computational and intelligence modeling analysis of pharmaceutical freeze drying for prediction of temperature in the process. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, N.T.; Long, N.T.; Duy, N.D.; Chien, N.N.; Van Phuong, N. Towards safer and efficient formulations: Machine learning approaches to predict drug-excipient compatibility. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 653, 123884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Fey, M.; Brecher, C. A survey on AI-driven digital twins in industry 4.0: Smart manufacturing and advanced robotics. Sensors 2021, 21, 6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, A.; Greif, L.; Häußermann, T.M.; Otto, S.; Kastner, K.; El Bobbou, S.; Chardonnet, J.-R.; Reichwald, J.; Fleischer, J.; Ovtcharova, J. Digital Twins, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing Reconfiguration: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.R.; Vasanth, P.M.; Ramesh, T.; Ramesh, M. Formulation and evaluation of lyophilized antibacterial agent. Int. J. Pharmtech Res. 2013, 5, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Ahammad, S.R.; Narayanasamy, D. A QbD approach for optimizing the lyophilization parameters of cyclophosphamide monohydrate. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2025, 51, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattni, B.S.; Chupin, V.V.; Torchilin, V.P. New Developments in Liposomal Drug Delivery. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 10938–10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S. Liposomes for drug delivery: Review of vesicular composition, factors affecting drug release and drug loading in liposomes. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Hu, C.M.J.; Fang, R.H.; Zhang, L. Liposome-like nanostructures for drug delivery. J. Mater Chem. B 2013, 1, 6569–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boafo, G.F.; Magar, K.T.; Ekpo, M.D.; Qian, W.; Tan, S.; Chen, C. The Role of Cryoprotective Agents in Liposome Stabilization and Preservation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atre, P.; Rizvi, S.A.A. A brief overview of quality by design approach for developing pharmaceutical liposomes as nano-sized parenteral drug delivery systems. RSC Pharm. 2024, 1, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonju, J.J.; Shrestha, P.; Dahal, A.; Gu, X.; Johnson, W.D.; Zhang, D.; Muthumula, C.M.R.; Meyer, S.A.; Mattheolabakis, G.; Jois, S.D. Lyophilized liposomal formulation of a peptidomimetic-Dox conjugate for HER2 positive breast and lung cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 639, 122950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzé, S.; Selmin, F.; Samaritani, E.; Minghetti, P.; Cilurzo, F. Lyophilization of liposomal formulations: Still necessary, still challenging. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas-Dodov, M.; Fredro-Kumbaradzi, E.; Goracinova, K.; Simonoska, M.; Calis, S.; Trajkovic-Jolevska, S.; Hincal, A.A. The effects of lyophilization on the stability of liposomes containing 5-FU. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 291, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.E.; Humphrey, J.R.; Laughton, C.A.; Thomas, N.R.; Hirst, J.D. Optimizing Excipient Properties to Prevent Aggregation in Biopharmaceutical Formulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommineni, N.; Butreddy, A.; Sainaga Jyothi, V.G.S.; Angsantikul, P. Freeze-drying for the preservation of immunoengineering products. iScience 2022, 25, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollenbach, L.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P. Poloxamer 188 as surfactant in biological formulations—An alternative for polysorbate 20/80? Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 620, 121706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.M.; Bandi, S.; Jones, D.N.M.; Mallela, K.M.G. Effect of Polysorbate 20 and Polysorbate 80 on the Higher-Order Structure of a Monoclonal Antibody and Its Fab and Fc Fragments Probed Using 2D Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 3486–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powar, T.; Hajare, A.; Jarag, R.; Nangare, S. Development and Evaluation of Lyophilized Methotrexate Nanosuspension using Quality by Design Approach. Acta Chim. Slov. 2021, 68, 861–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, T.; Itaya, M.; Burdeos, G.C.; Nakagawa, K.; Miyazawa, T. A critical review of the use of surfactant-coated nanoparticles in nanomedicine and food nanotechnology. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 3937–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, K.B.; Randolph, T.W. Stability of lyophilized and spray dried vaccine formulations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 171, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, D.; Ramsey, J.D.; Kabanov, A.V. Polymeric micelles for the delivery of poorly soluble drugs: From nanoformulation to clinical approval. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 156, 80–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikala, R.; Eerola, R.; Tanninen, V.P.; Yliruusi, J. Polymorphic changes of mannitol during freeze-drying: Effect of surface- active agents. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 1997, 51, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nnadili, M.; Okafor, A.N.; Olayiwola, T.; Akinpelu, D.; Kumar, R.; Romagnoli, J.A. Surfactant-specific ai-driven molecular design: Integrating generative models, predictive modeling, and reinforcement learning for tailored surfactant synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 6313–6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, J.; Morozov, K.I.; Wu, Z.; Xu, T.; Rozen, I.; Leshansky, A.M.; Li, L.; Wang, J. Highly efficient freestyle magnetic nanoswimmer. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 5092–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza Mozafari, M. Nanomaterials and Nanosystems for Biomedical Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Potara, M.; Nagy-Simon, T.; Focsan, M.; Licarete, E.; Soritau, O.; Vulpoi, A.; Astilean, S. Folate-targeted Pluronic-chitosan nanocapsules loaded with IR780 for near-infrared fluorescence imaging and photothermal-photodynamic therapy of ovarian cancer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 203, 111755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankali, E.; Shaabanzadeh, M.; Torbati, M.B. Fluorescent tamoxifen-encapsulated nanocapsules functionalized with folic acid for enhanced drug delivery toward breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and cancer cell imaging. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechnak, L.; El Kurdi, R.; Patra, D. Fluorescence Sensing of Nucleic Acid by Curcumin Encapsulated Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Block-Poly(Propylene Oxide)-Block-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Based Nanocapsules. J. Fluoresc. 2020, 30, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Gu, Z. Enzyme Nanocapsules for Glucose Sensing and Insulin Delivery. In Biocatalysis and Nanotechnology; Pan Stanford Publishing Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Jain, A.; Cring, M.; Searby, C.; Sheffield, V.C. Positively Charged TPGS-Chiotsan Nanocapsules as a Non-Viral Vector for Glaucoma Gene Therapy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 2896. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Zhao, N.; Xu, F.J. Rattle-Structured Rough Nanocapsules with in-Situ-Formed Gold Nanorod Cores for Complementary Gene/Chemo/Photothermal Therapy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5646–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Remuñán-López, C.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Alonso, M.J. Development of positively charged colloidal drug carriers: Chitosan-coated polyester nanocapsules and submicron-emulsions. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1997, 275, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.; Chauhan, S.; Nagaich, U.; Jain, N. Current advances in chitosan nanoparticles based drug delivery and targeting. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolluru, L.P.; Atre, P.; Rizvi, S.A.A. Characterization and applications of colloidal systems as versatile drug delivery carriers for parenteral formulations. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, S.A.A.; Saleh, A.M. Applications of nanoparticle systems in drug delivery technology. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Y.; Rizvi, S.A.A.; Yousaf, A.M.; Hussain, T. Drug Delivery Using Nanomaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Barradas, M.E.; Márquez, M.; Quintanar, L.; Santoyo-Salazar, J.; Espadas-Álvarez, A.J.; Martínez-Fong, D.; García-García, E. Development of a parenteral formulation of NTS-polyplex nanoparticles for clinical purpose. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fang, G.; Gou, J.; Wang, S.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y. Lyophilization of self-assembled polymeric nanoparticles without compromising their microstructure and their in vivo evaluation: Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and toxicity. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2015, 5, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotwe-Otoo, D.; Khan, M.A. Lyophilization of Biologics: An FDA Perspective. In Lyophilized Biologics and Vaccines; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Awotwe-Otoo, D.; Agarabi, C.; Wu, G.K.; Casey, E.; Read, E.; Lute, S.; Brorson, K.A.; Khaln, M.A.; Shah, R.B. Quality by design: Impact of formulation variables and their interactions on quality attributes of a lyophilized monoclonal antibody. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 438, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, H.; Sotolongo, J.; González, Y.; Hernández, G.; Chinea, G.; Gerónimo, H.; Amarantes, O.; Beldarraín, A.; Páez, R. Stabilization of a recombinant human epidermal growth factor parenteral formulation through freeze-drying. Biologicals 2014, 42, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraan, H.; Van Herpen, P.; Kersten, G.; Amorij, J.P. Development of thermostable lyophilized inactivated polio vaccine. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, M.; Fu, Z.F.; Zhao, L. Circular RNA vaccines with long-term lymph node-targeting delivery stability after lyophilization induce potent and persistent immune responses. mBio 2024, 15, e0177523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoola, M.; Niazi, S.K. Current Progress and Future Perspectives of RNA-Based Cancer Vaccines: A 2025 Update. Cancers 2025, 17, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravante, F.; Sacchini, F.; Mancin, S.; Lopane, D.; Parozzi, M.; Ferrara, G.; Sguanci, M.; Palomares, S.M.; Biondini, F.; Marfella, F.; et al. Preventing Microorganism Contamination in Starting Active Materials for Synthesis from Global Regulatory Agencies: Overview for Public Health Implications. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C. FDA 2011 Process Validation Guidance: Lifecycle Compliance Model. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2014, 68, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.; Mahler, H.-C.; Mellman, J.; Nieto, A.; Wagner, D.; Schaar, M.; Mathaes, R.; Kossinna, J.; Schmitting, F.; Dreher, S.; et al. Container Closure Integrity Testing—Practical Aspects and Approaches in the Pharmaceutical Industry. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2016, 71, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirakhori, F.; Niazi, S.K. Harnessing the AI/ML in Drug and Biological Products Discovery and Development: The Regulatory Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).