Abstract

Background/Objectives: Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) are the gold standard to measure fat mass, but they are unavailable in regular consultations. Relative Fat Mass (RFM) and Pediatric Relative Fat Mass (pRFM) equations are calculated using DXA images in adults and children, but they have not been correlated with BIA. Methods: A longitudinal prospective study was conducted with 531 children from a public school followed over one year; sex, age, weight, height, waist circumference and fat mass percentage were recorded. We calculated body mass index Z-score (Z-BMI), body mass index percentile (Pc BMI), waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and RFM-pRFM to diagnose Overweight (Ow)/Obesity (Ob). We used descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlation, sensitivity and specificity, 95% CI, and ROC curves; SPSS version 22 was used. Results: Adiposity was found in 34.5%, 33.2%, 21.5% and 43.5% of children using Z-BMI, Pc BMI, WHtR, and BIA, respectively; excluding children younger than 8 years old, the frequency of adiposity was 51.5% by RFM-pRFM. The highest correlation was between RFM-pRFM and BIA (0.84, p < 0.000). Of the total measurements of each visit considered as normal weight using Z-BMI, 21.5% had adiposity using BIA, and the proportion of girls underdiagnosed was twice that of boys. Conclusions: RFM-pRFM had the highest correlation with BIA but Z-BMI, Pc BMI, and WHtR are also helpful. It is important to consider that 21.5% of children with apparent normal weight present adiposity.

1. Introduction

Current evidence shows that one of five children or adolescents (22.2%) present overweight or obesity (adiposity), 14.8% overweight and 8.5% obesity in the world [1]. The ENSANUT (Mexican National Survey) 2020–2022 reported a prevalence of overweight and obesity of 37% in schoolchildren (5–11 years) and 41% in adolescents, 24% more in schoolchildren and 50% more in adolescents compared to 2006 [2,3]. According to the most recent global meta-analysis [1,4], the prevalence of childhood obesity (only obesity and not overweight) estimated by the WHO is 8.6%, 5.4% by the IOTF, and 14.5% by the CDC. Given this alarming trend and the use of different diagnostic methods, it is important to unify criteria for diagnosis.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is considered the gold standard for measuring body composition, but it is not feasible for large populations due to cost, limited accessibility, and risk of exposure to ionizing radiation; this is unsuitable for repeated use in children. Instead, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is a more practical diagnostic tool, and its correlation has been reported to be up to 0.959 with DXA in 7-year-old children (boys and girls) with fat mass index [5]. Other authors found that, in 14-year-old children with obesity and severe obesity, there is 0.95 correlation with DXA [6]. BIA is useful to diagnose and give a better follow-up for children with adiposity. Recently, Woolcott et al. studied several DXA images in adults and children to calculate Relative Fat Mass (RFM) equation to measure fat mass, and they did an adjustment for children between 8 and 14 years old: Pediatric Relative Fat Mass (pRFM) [7]. In Mexican children, Costa Urrutia et al. identified ≥30% in girls and ≥25% in boys as an indicator of cardiometabolic risk and obesity using BIA [8]. Currently, no universal cutoff point exists for defining overweight based on body fat percentage in children. In the pediatric population, we used WHO criteria (BMI Z- score 1–1.99 = overweight, ≥2 = obesity) and CDC criteria (BMI-for-age percentiles ≥ 85th = overweight and ≥95th = obesity) [9]. Some authors have reported that using only the BMI Z-score, 46.4% could be misdiagnosed when fat mass is measured by DXA [10]. BMI percentiles (85 or higher) by CDC curves has shown an association with health problems and higher mortality when they become adults [11,12]. On the other hand, waist height rate (WHtR) ≥0.5 is considered a good marker of visceral fat and cardiometabolic risk [13,14].

DXA is expensive, and it is not widely available and involves radiation; BIA is safer and more available, but it is not common to use it in regular consultations. Therefore, RFM-pRFM could be a helpful diagnostic alternative to calculate body fat percentage in pediatric patients [7], but it has not yet been correlated with BIA, which is important because it is easier to compare diagnoses and principal outcomes of children with adiposity during their follow-up.

Our objective was to diagnose adiposity (overweight/obesity) using different diagnostic methods, to correlate them vs. BIA, the gold standard, and to identify cases of misdiagnosis.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This is a longitudinal prospective study performed in a public school population with duration of 1 year of follow-up and visits every 3 months. The total number of eligible children was 698 students who were 6 to 18 years old, of which 76% of children and their parents accepted to participate in our study. Of a total of 531 children and 1926 measurements, we excluded 426 measurements due to the age being <8 years old and few cases due to not attending school, having metals in their bones, or physical limitations to be measured using BIA. Children younger than 8 years old were excluded because the pRFM equation considers only 8 years old or more. The median age of children in the 1500 measurements was 12.23 years old (range: 8–17), and 56.5% were female. The inclusion criteria included being a student at the school, and exclusion criteria were having a metal in their bone structure or a physical impossibility to be measured by BIA.

2.2. Subjects

We recorded sex, age, weight, height, waist circumference, and body composition by BIA in the basal visit and each visit. We also calculated Body Mass Index-Z score (Z-BMI) with WHO software Anthro Plus 1.0.4, 2007, Percentile of BMI -Pc BMI- using CDC curves, and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) as the waist circumference in centimeters divided by the height in centimeters and fat mass percentage using the Relative Fat Mass (RFM) and pediatric Relative Fat Mass (pRFM) equations (Table 1). Misdiagnosed cases were considered the children diagnosed with adiposity but with normal fat mass percentage (overdiagnosis) and children with normal weight but high fat mass percentage by BIA (underdiagnosis).

Table 1.

Equations of Relative Fat Mass (RFM) and Pediatric Relative Fat Mass (pRFM).

All measurements were taken by the same trained physicians and nutritionists who were standardized and also were the same in each visit, and each one took the same measures as weight, height, waist, and body fat percentage using the same devices. For the waist measurement, we used a tape measure and followed the recommendations of the WHO. The measurements were taken with the patient standing, taking as reference the midpoint between the lower edge of the last palpable rib and the upper edge of the iliac crest. The patient is asked to inhale and exhale without exerting force on the abdominal muscles. The measurement should be taken after normal exhalation. Each measurement is repeated twice; if they have a variation greater than one centimeter, the measurement was repeated. The height was determined in a BSM 120 InBody digital stadiometer made in South Korea. Weight and body fat mass percentage were determined using the same devices, InBody Biospace 120, made in South Korea.

Participants were instructed to hydrate adequately one day before the measurement, wear light clothing, not eat at least two hours before the test, not exercise eight hours before, go to the bathroom beforehand, have clean palms and soles, and remove shoes, socks, electronic devices and jewelry. A parent representative and a teacher were present when the measurements were taken in groups of 20 children approximately every 30–40 min.

We first diagnosed the frequency of Overweight (Ow) and Obesity (Ob) in all participants of each visit using the different diagnostic methods. The percentage of body fat measured by BIA was considered obesity using the cutoff point ≥25% in boys and ≥30% in girls [8]. WHtR was considered altered if it was ≥0.5 [12,13]. In order to correlate the different diagnostic methods, we only used 1500 measurements out of a total of 1926 because pRFM has not been used in children under 8 years old. We used descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlation, sensitivity and specificity, 95%CI, and COR curves through SPSS version 22.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board at the Instituto Nacional de Perinatología (Reference No. 2018-1-177), and written informed consent was obtained from parents and children.

3. Results

In Table 2, we show the percentages of Ow/Ob using Z-BMI, Pc-BMI, fat mass as obesity using cutoff point ≥25% in boys and ≥30% in girls [8], and altered WHtR in each visit for all children, even those younger than 8 years old.

Table 2.

Frequencies (percentages) of adiposity (Ow/Ob) using different methods in each visit.

We measured Pearson’s correlation between BIA and WHtR, RFM-pRFMp, Z-BMI, and Pc-BMI in the 1500 measurements of children who were 8 years old or older in order to use RFM-pRFM equations. Pc BMI and Z-BMI had the highest correlation between both, but comparing with BIA, Z-BMI had a better correlation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation among different diagnostic tools.

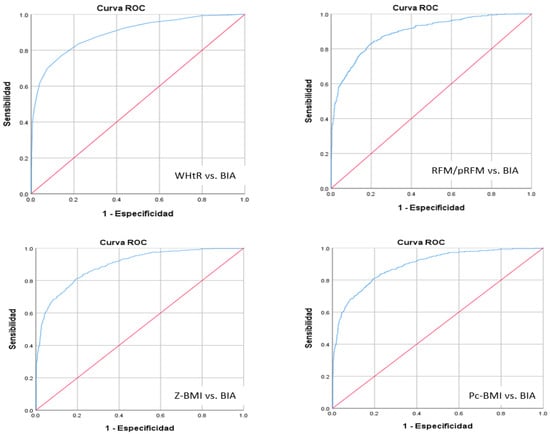

Of the total measurements of each visit considered as normal weight using Z-BMI, 21.5% had adiposity using BIA, and the proportion of girls underdiagnosed was twice that of boys. On the other hand, only 10% of the measurements defined as overweight or obesity had normal fat mass percentage by BIA. So then, the total percentage of misdiagnoses was 31.5%. We found the best sensitivity and specificity for WHtR of 0.46, RFM/pRFM of 28.9, Z-BMI of 0.57, and Pc BMI of 66.35. Figure 1 and Table 4.

Figure 1.

The AUC according to diagnostic method WHtR, RFM/pRFM, Z-BMI and Pc BMI vs. BIA. The sensitivity (the proportion of true positive results) is shown on the y axis, going from 0 to 1 (0–100%) and 1-specificity (the proportion of false positive results) is shown on the x axis, going from 0 to 1 (0–100%).

Table 4.

Different diagnostic methods considering area under curve and confidence interval.

The four diagnostic methods had good sensitivity and specificity with statistical significance and acceptable confidence interval.

4. Discussion

This study presents the frequency of adiposity (overweight/obesity) measured during the follow-up of 531 children and adolescents, using different methods for comparison with BIA (the most accurate method after DXA).

It is important to remember that although we obtained a total of 1926 measurements during the follow-up, we could not include 426 measurements of children younger than 8 years old because pRFM has been calculated only in children ≥8 years old. The frequencies of Ow and Ob (Table 2) were very similar between Z-BMI and Pc BMI, but Ow was almost twice using Z-BMI compared to using Pc BMI.

We found that the frequency of adiposity by BIA was 44%, 10% higher that Ow/Ob diagnosed by Z-BMI and Pc BMI, but if we had considered only obesity according to Z-BMI ≥ 2 and Pc BMI ≥ 95, the diagnosis by BIA would have been four times more than that using Z-BMI, almost three times more than that using Pc BMI and two times more than that using WHtR. Furthermore, RFM/pRFM slightly overdiagnoses adiposity but it had the best correlation with fat mass percentage by BIA. Sometimes, overweight and obesity are not clearly differentiated, even when reporting statistics about their frequencies [1,2,3,4]. In our study, we found a lower percentage of underdiagnosis than that reported by other authors [6], but this involved joining both conditions of Ow/Ob as classified by Z-BMI and Pc BMI. When we compare the fat mass percentage only with Ob using these two methods, the high level of underdiagnosis is similar to the results of other studies. It is important to join both conditions and consider a new cutoff point to diagnose overweight. This cutoff point could be 75 Pc BMI as other authors have suggested [11,15], but based on our results, we suggest 66.35 as the cutoff point. It is also necessary to find cutoff points for body fat percentage to classify overweight, not just obesity, mainly because parents do not realize the magnitude of excess weight in their children [16,17]; they will perhaps be able to better understand their physical condition by knowing the amount of body fat percentage. In the future, we will try to analyze how children and parents can better understand their diagnosis and results, whether it is body fat percentage, BMI percentile curves, or a combination of different diagnostic methods.

Another problem is the lack of standardization for the definition criteria of Ow and Ob because some authors use different cutoff points in Z-BMI or Pc BMI. Chavira-Suarez et al. defined overweight with Z-BMI 2 < 3 and obesity with 3 or more and pathologic WHtR using percentiles (65th in girls and 77th in boys) [18,19]. According to reports of the latest global prevalence, 22.3% of children have Ow/Ob [20] and 34% in this study by Z-BMI, but using BIA, the most accurate method, 44% of the measurements in our study participants showed twice the amount of obesity as the global prevalence rate. However, we cannot compare frequencies with this method because the percentage of fat mass is not reported in the worldwide cross-sectional studies [20,21] and even less so in longitudinal ones. Nonetheless, we found similar frequency of obesity with this more precise method (BIA), as reported by Costa-Urrutia in 2019. This is not a good prognostic because despite governmental efforts, there was no decrease in this high frequency. On the other hand, the frequency of adiposity measured by BIA was twice as high in women compared to men. This is concerning due to its role in the metabolic programming of new generations [22,23,24]. Efforts need to be directed at reducing this high frequency in all children, but especially in girls.

We found the highest Pearson’s correlation between BIA and RFM; thus, in the absence of BIA, RFM-pRFM could be used, principally in order to obtain a better approximation of fat mass percentage if physicians or nutritionists do not have DXA or BIA and they can complement the measurement with WHtR. The second highest Pearson’s correlation was for Z-BMI; therefore this is also a good method for diagnosis. However, when we used COR curves, we found very similar precision to the rest of the diagnostic methods, but we included children with overweight.

Therefore, we suggest using the BIA whenever possible, or at least the RFM-pRFM. Recently, the use of two or more different methods has been proposed to diagnose adiposity, including the presence of complications [25]. Although WHtR is considered to indicate visceral fat and cardiovascular risk [26,27,28], using it in a systematic way could be helpful if physicians do not have BIA or time to calculate RFM-pRFM.

In our comprehensive program “Sacbe” (Mayan word that means “White Way”) to prevent and treat adiposity in children, we have achieved promising results to decrease BMI Z-score due to several factors [29,30]. From a qualitative point of view, we observed that if children and their parents realize the percentage of fat mass in their bodies, they show a better disposition to make changes; therefore, using BIA or RFM-pRFM could also offer great utility in improving adherence. In general, diagnosis of Ow/Ob, Z-BMI and Pc BMI showed good correlation with BIA, but to obtain a more precise measurement of amount of fat mass (%), RFM-pRFM and WHtR are more helpful methods.

5. Conclusions

RFM-pRFM had the highest correlation with BIA, but the sensibility and specificity were adequate for the four diagnostic methods. One in five children with normal weight by Z-BMI had adiposity, and twice the number of girls presented adiposity as boys. Thus, we should use RFM-pRFM and WHtR if BIA or DXA is unavailable, although Z-BMI and Pc BMI also are helpful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.-V. and L.F.F.-S.; methodology, all authors; software A.R.-V.; validation, A.R.-V., L.F.F.-S. and N.Z.-P.; formal analysis, A.R.-V., L.F.F.-S., N.Z.-P. and D.P.; investigation, all authors; resources, A.R.-V.; data curation, A.R.-V., L.F.F.-S. and N.Z.-P.; writing-original draft preparation, N.Z.-P.; writing-review and editing, A.R.-V.; visualization, all authors; supervision A.R.-V.; Project administration, A.R.-V.; funding acquisition, A.R.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONAHCYT grant number 6708 (2019), and Fundación Gonzalo Río Arronte grant number S697 (2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Perinatology Institute Research and Ethics Committee (protocol code 2018-1-177 and date of approval 20 March 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the study can be requested through the corresponding author within a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Christel House School authorities, Fernando Guerra, Gabriel Arteaga, and Mario Tapia; Claudia Leal, Minerva Hernandez-Flores, Paola Hamilton, Jessica Rodríguez, Alejandra Navarrete, Ana Fuentes and Julián Uriarte.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Ni, Y.; Yi, C.; Fang, Y.; Qingyng, N.; Shen, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Global Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G.; Méndez Gómez-Humarán, I.; Ávila-Arcos, M.A. Childhood obesity in Mexico: Influencing factors and prevention strategies. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 949893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Morales-Ruan, C.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G.; Méndez-Gómez Humaran, I.; Ávila-Arcos, M.A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the school-age and adolescent population in Mexico. Ensanut Continua 2020–2022. Public Health Mex. 2023, 65, s218–s224. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca-Colomer, F.; Murillo-Llorente, M.T.; Legidos-García, M.E.; Palau-Ferré, A.; Pérez-Bermejo, M. Differences in Classification Standards For the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 14, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, V.; Closa-Monasterolo, R.; Rubio-Torrents, C.; Zaragoza-Jordana, M.; Ferré, N.; Gispert-Llauradó, M.; Escribano, J. Bioimpedance in 7-year-old children: Validation by dual X-ray absorptiometry—Part 1: Assessment of whole body composition. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014, 64, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Xanthakos, S.A.; Hornung, L.; Arce-Clachar, C.; Siegel, R.; Kalkwarf, H.J. Relative Accuracy of Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis for Assessing Body Composition in Children With Severe Obesity. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020, 70, e129–e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Woolcott, O.O.; Bergman, R.N. Relative Fat Mass as an estimator of whole-body fat percentage among children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study using NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costa-Urrutia, P.; Vizuet-Gámez, A.; Ramirez-Alcántara, M.; Guillen-González, M.Á.; Medina-Contreras, O.; Valdes-Moreno, M.; Musalem-Younes, C.; Solares-Tlapechco, J.; Granados, J.; Franco-Trecu, V.; et al. Obesity measured as percent body fat, relationship with body mass index, and percentile curves for Mexican pediatric population. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Styne, D.M.; Arslanian, S.A.; Connor, E.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Murad, M.H.; Silverstein, J.H.; Yanovski, J.A. Pediatric Obesity—Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 2017, 102, 709–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasor-Ortolá, D.; Quesada-Rico, J.A.; Nso-Roca, A.P.; Rizo-Baeza, M.; Cortés-Castell, E.; Martínez-Segura, A.; Sánchez-Ferrer, F. Degree of Accuracy of the BMI Z-Score to Determine Excess Fat Mass Using DXA in Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.; Kelly, J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.L.; Mihrshahi, S.; Gale, J.; Drayton, B.; Bauman, A.; Mitchell, J. 30-year trends in overweight, obesity and waist-to-height ratio by socioeconomic status in Australian children, 1985 to 2015. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Ribas, L.; Koebnick, C.; Funtikova, A.; Gomez, S.F.; Fíto, M.; Perez-Rodrigo, C.; Serra-Majem, L. Prevalence of Abdominal Obesity in Spanish Children and Adolescents. Do We Need Waist Circumference Measurements in Pediatric Practice? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, A.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Siegel, R.M.; Fogelman, Y.; Dubnov-Raz, G. Using weight-for-age percentiles to screen for overweight and obese children and adolescents. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ventura, A.L.; Pelaez-Ballestas, I.; Sámano-Sámano, R.; Jimenez-Gutierrez, C.; Aguilar-Salinas, C. Barriers to lose weight from the perspective of children with overweight/obesity and their parents: A sociocultural approach. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 575184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samano, R.; Rodríguez-Ventura, A.L.; Sanchez-Jimenez, B.; Martinez, E.Y.G.; Noriega, A.; Zelonka, R.; Garza, M.; Nieto, J. Body image satisfaction in mexican adolescents and adults and its relation with body selfperception and real body mass index. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavira-Suarez, E.; Rosel-Pech, C.; Polo-Oteyza, E.; Ancira-Moreno, M.; Ibarra-Gonzalez, I.; Vela-Amieva, M.; Meraz-Cruz, N.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. Simultaneous evaluation of metabolomic and inflammatory biomarkers in children with different body mass index (BMI) and waist-to height ratio (WHtR). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44583 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- GBD 2021 Adolescent BMI Collaboraters. Global, regional, and national prevalence of child and adolescent overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I.; Brett, E.M.; Garber, A.J.; Hurley, D.L.; Jastreboff, A.M.; Nadolsky, K.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Plodkowski, R. Reviewers of AACE/ACE Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist and American College of Endocrinology: Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Medical Care of patients with obesity. Endocr. Pract. Off. J. Am. Coll. Endocrinol. Am. Assoc. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S3), 1–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, M.W.; Kallapur, S.G.; Jobe, A.H.; Newnham, J.P. Obesity and the developmental origins of health and disease. J. Pediatr. Child Health 2012, 48, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano, E.; Ibáñez, C.; Martinez-Samayoa, P.; Lomas-Soria, C.; Durand-Carbajal Rodríguez-Gonzalez, G.L. Maternal Obesity: Lifelong Metabolic Outcomes for Offspring from Poor Developmental Trajectories During the Perinatal Period. Arch. Clin. Res. 2016, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giza, S.A.; Sethi, S.; Smit, L.M.; Empey, M.E.E.T.; Morris, L.E.; McKenzie, C.A. The application of in utero magnetic resonance imaging in the study of the metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of the developmental origins of health and disease. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2021, 12, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A.; Stanford, F.C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Metzger, D.L.; Daymont, C.; Hadjiyannakis, S.; Rodd, C.J. LMS tables for waist-circumference and waist-height ratio Z-scores in children aged 5–19 y in NHANES III: Association with cardio-metabolic risks. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm, A.; Roswall, J.; Alm, B.; Almquist-Tangen, G.; Bremander, A.; Dahlgren, J.; Staland-Nyman, C.; Bergman, S. Body Mass Index Classification Misses to Identify Children With an Elevated Waist-to-Height Ratio at 5 Years of Age. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsma, A.; Bocca, G.; L’Abée, C.; Liem, E.T.; Sauer, P.J.; Corpeleijn, E. Waist-to-Height Ratio, Waist Circumference and BMI as Indicators of Percentage Fat Mass and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Children Aged 3-7 Years. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ventura, A.; Parra-Solano, A.; Illescas-Zárate, D.; Hernández-Flores, M.; Paredes, C.; Flores-Cisneros, C.; Sánchez, B.; Tolentino, M.; Sámano, R.; Chinchilla, D. “Sacbe”, a Comprehensive Intervention to Decrease Body Mass Index in Children with Adiposity: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Solano, A.; Hernández-Flores, M.; Sánchez, B.; Paredes, C.; Monroy, L.; Palacios, F.; Almaguer, L.; Rodriguez-Ventura, A. Reducing the Number of Times Eating Out Helps to Decrease Adiposity (Overweight/Obesity) in Children. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).