Abstract

Central sensitization of pain (CSP) is defined as the “increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) to normal or subthreshold afferent input” The primary objective of this study is to compare the prevalence of CSP between patients presenting with foot and ankle conditions and those presenting with low back pain. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted comparing a cohort of patients with a first consultation for foot and ankle disorders to another cohort with a first consultation for lumbar spine pain at the same institution. Demographic variables, pain duration, main diagnosis, and a series of questionnaires assessing pain and disability were collected. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI) was administered to determine the presence of CSP within the groups. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA. Results: A total of 195 patients presenting with foot/ankle conditions and 252 patients with low back pain were included. Among the foot/ankle cohort, 16.4% (95% CI, 10.92–21.9%) were classified as having CSP, compared to 22.2% (95% CI, 16.85–27.6%) in the lumbar pain cohort. The difference in CSP prevalence between groups was not statistically significant (difference 5.79%, Chi2 = 2.357, p = 0.125). However, the difference in mean scores on Part A of the CSI was statistically significant (31.82 ± 13.88 vs. 25.20 ± 14.31, z = 4.237, p < 0.001). Among foot/ankle pathologies, plantar fasciitis showed the highest prevalence of CSP (21.9%), followed by hallux valgus (18.8%). A significant association was observed between CSP and higher levels of pain and disability. Female patients demonstrated a higher prevalence of CSP. Conclusions: Patients with low back pain exhibited higher CSI scores and a greater prevalence of central sensitization compared with those with foot and ankle disorders. Recognizing these mechanisms may help clinicians tailor more effective, multidisciplinary treatment strategies.

1. Introduction

Central sensitization of pain (CSP) is defined as the “increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) to normal or subthreshold afferent input [1].” Pain is one of the leading reasons for medical consultation worldwide and represents a major challenge for clinicians due to its complex and multifactorial nature. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or similar to that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” [2]. This definition underscores both the subjective nature of pain and the fact that it may not always correlate directly with identifiable tissue injury.

From a pathophysiological perspective, pain can be categorized into three main types: nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, and pain due to central sensitization (CS). Nociceptive pain arises from the activation of nociceptors by chemical, mechanical, or thermal stimuli in non-neuronal tissues [3,4]. Neuropathic pain, by contrast, is caused by a primary lesion or disease of the somatosensory system, and can be peripheral (nerve, plexus, dorsal root ganglion) or central (spinal cord or brain) in origin [3,5]. A distinguishing clinical feature of neuropathic pain is its restriction to a neuroanatomically plausible distribution, directly related to the affected nervous structure [3].

Central sensitization pain (CSP) represents a third category, defined by the IASP as “increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to normal or subthreshold afferent input” [1]. Clifford J. Woolf first described this phenomenon in the early 1980s, drawing upon the spinal gate control hypothesis. This model proposes that nociceptive signaling can be attenuated through the activation of inhibitory mechanisms, via either peripheral inhibitory fibers or descending modulatory pathways originating from the brainstem, which act by reducing the transmission of pain signals at the level of the spinal cord. Consequently, impairment or reduction of these inhibitory pathways results in enhanced pain perception in affected patients [6]. In this setting, pain loses its protective biological role and manifests as spontaneous pain, pain evoked by normally innocuous stimuli (allodynia), exaggerated or prolonged responses to noxious stimuli (hyperalgesia), and spreading of pain beyond the initial site of injury (secondary hyperalgesia) [4,7]. SCD is reflected in the term nociplastic pain, recently included by the IASP, which defines it as pain originating from an alteration of nociception with sensitisation as the main underlying mechanism [7].

Understanding the mechanisms underlying different pain phenotypes has important clinical implications. Identifying CS not only improves diagnostic accuracy and prognosis but also opens the door to novel therapeutic strategies aimed at controlling persistent pain and improving quality of life in affected patients [1,7].

Among chronic pain conditions, low back pain (LBP) is one of the most prevalent and disabling worldwide. Lifetime prevalence estimates range from 70% to 85% in adults, making it a major cause of disability and socioeconomic burden [3]. Increasing evidence indicates that CS is present in a subgroup of patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) [8,9]. A systematic review estimated its prevalence in this population at approximately 48.9%, although significant heterogeneity and disagreement persist across studies [10].

While CS has been extensively investigated in LBP [11] and other musculoskeletal disorders, its role in foot and ankle pathologies remains largely unexplored. These conditions are frequent causes of chronic pain and functional limitation, yet the possible contribution of central mechanisms has not been adequately addressed. Establishing whether CS contributes to pain chronicity in foot and ankle disorders would not only provide new insights into their pathophysiology but could also have practical consequences for clinical management [7].

To facilitate the detection of CS in clinical settings, the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI) was developed and validated [12]. This questionnaire allows clinicians to identify patients with a high probability of CS and has been widely applied in chronic pain populations. Nonetheless, debate remains regarding the most appropriate cut-off values to define clinically relevant sensitization, with some authors advocating for a threshold of 40 points [13] and others supporting lower cut-offs [14].

In this context, a direct comparison of CS prevalence between patients with LBP and those with foot and ankle pathologies could clarify the clinical importance of central mechanisms across different musculoskeletal disorders. Furthermore, identifying associations between CS and demographic, clinical, and quality-of-life variables would contribute to significant understanding of its impact on patient outcomes.

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of CS, as assessed by the CSI, in patients presenting for the first time with LBP compared with those presenting with foot and ankle pathology at the University of Navarra Clinic (CUN). In addition, we sought to examine the potential associations between CS and other clinical and demographic variables collected in both patient groups.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study conducted at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology of CUN. Data were collected prospectively over a three-month period (September to December 2023) from adult patients who attended their first consultation for either LBP or foot and ankle pathology.

A “first consultation” was defined as the initial clinical visit to the department for a new musculoskeletal complaint, without prior assessment, diagnosis, or medical treatment of the same condition at our center.

Eligible participants were adults (≥18 years) presenting for their first consultation with one of the two target conditions. The LBP group included patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP), persisting for ≥12 weeks, with or without associated radicular symptoms. The foot and ankle group comprised patients with structural, degenerative, traumatic, or overuse-related pathologies (e.g., hallux valgus, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, ankle instability, post-traumatic deformities, or osteoarthritis).

Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, if they attended the department for follow-up of a previously diagnosed condition, or if their consultation was unrelated to the inclusion criteria. All participants were informed about the objectives of the study and provided written informed consent prior to inclusion.

Upon recruitment, all patients completed self-administered questionnaires during their consultation. In the group of patients presenting with LBP, the following data were collected: sex, age, reason for consultation, duration of symptoms in months, and pain intensity assessed with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). In addition, pain in the affected lower limb was specifically assessed using the VAS, disability was measured with the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), a questionnaire for assessing the degree of disability caused specifically by low back pain [15]. Health-related quality of life was evaluated with the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [16]. CS was assessed using the CSI Part A, while Part B of the CSI was used to record previous diagnoses of other conditions associated with CS [12]. The clinical diagnosis provided at the consultation was also registered.

For patients presenting with foot and ankle pathology, a similar protocol was followed. Data included sex, age, reason for consultation, duration of symptoms, and pain intensity measured with the VAS. Functional status was assessed using the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) for both activities of daily living and sports performance [17,18]. Health-related quality of life was also evaluated with the SF-12 [16]. CS and associated diagnoses were measured using the CSI, Parts A and B [12], and the final clinical diagnosis was recorded. CS was defined using the CSI, applying a cut-off score of greater than 40 points in Part A, consistent with prior studies [13].

A descriptive analysis was performed for all variables. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), while categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons were conducted using Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, depending on their distribution. Normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homoscedasticity with Levene’s test. For categorical variables, either the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA software version 14.

The study was conducted retrospectively with anonymized data, and according to the regulations in place at our institution/country at the time the research began. The work was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, and data confidentiality was maintained at all times.

3. Results

A total of 447 patients were included in the study, of whom 259 (57.9%) were women and 188 (42.1%) were men, with a mean age of 55.05 ± 16.06 years.

The mean duration of pain was 19.97 ± 29.66 months (Table 1) and the mean VAS score for patients’ chief complaint (low back pain and foot or ankle pain for each group) was 5.85 ± 2.52. The mean scores on the SF-12 were 38.63 ± 11.39 for the physical component (SF-12P) and 51.15 ± 10.32 for the mental component (SF-12M). In the subgroup of patients with LBP, the mean lower-limb VAS score was 3.79 ± 3.11 and the ODI was 25.63 ± 16.73%. Among those with foot and ankle pathology, the FAAM averaged 71.0 ± 22.25% for activities of daily living and 52.26 ± 28.57% for sports activity.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients at first consultation for LBP and foot and ankle pathology. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (95% confidence interval) or as absolute number (percentage).

The mean score for Part A of CSI was 28.94 ± 14.43; 88 patients (19.7%) scored >40 points and 305 (68.2%) scored <40. In Part B, 269 patients (60.2%) reported no comorbidities, 110 (24.6%) reported one, 37 (8.3%) two, 20 (4.5%) three and 11 (2.5%) four or more (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of patients for the entire population and both groups. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (95% confidence interval) or as absolute number (percentage).

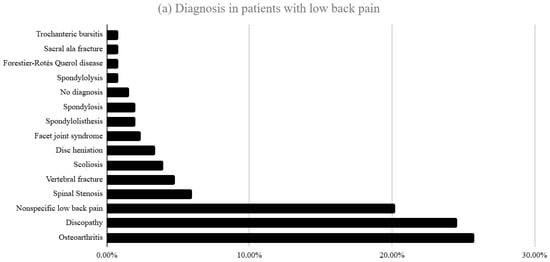

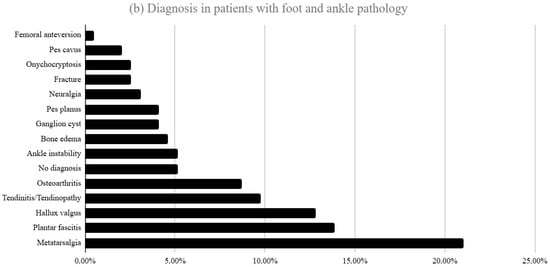

Figure 1a,b show the most frequent diagnosis of the studied patients. Of the total cohort, 252 patients (56.4%) consulted LBP and 195 (43.6%) for foot/ankle disorders. In the low back pain group, isolated lumbar pain (59.9%) and lumbar pain with radiation to the lower limb (23.4%) were the most frequent complaints. The most frequent diagnoses in patients with low back pain were osteoarthritis (25.8%), discopathy (24.6%) and non-specific low back pain (20.2%). In the foot/ankle group, plantar pain (24.1%), non-specific foot pain (19.5%) and ankle pain (14.4%) predominated.

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of diagnoses among patients presenting with LBP at their first consultation (b) Diagnoses in patients presenting with foot and ankle pathology at first consultation.

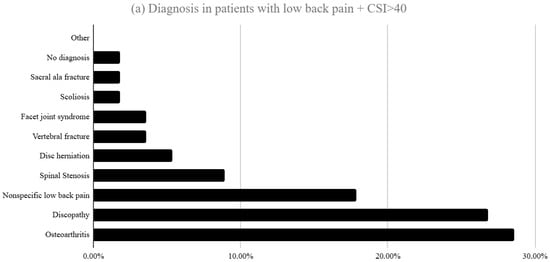

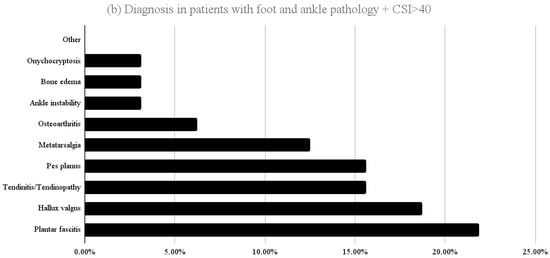

The diagnoses corresponding to patients who scored >40 in part A of the CSI are shown in Figure 2. In the LBP group the highest proportions corresponded to osteoarthritis (28.6%), discopathy (26.8%) and non-specific low back pain (17.9%). In the foot/ankle group, the most prevalent were plantar fasciitis (21.9%), hallux valgus (18.8%), tendinitis/tendinopathy (15.6%) and flatfoot (15.6%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of diagnoses among patients who scored >40 in part A of the CSI (a) presenting with LBP and (b) presenting with foot and ankle pathology at first consultation.

Women predominated in both groups (56% in low back pain and 60.5% in foot/ankle disorders) with no significant difference (Chi2 = 0.9382; p = 0.333). Mean age was higher in the low back pain group (56.6 ± 16.74 years) than in the foot/ankle group (53.05 ± 14.95 years) (z = 2.059; p = 0.0395). Symptom duration was also longer in the low back pain group (23.26 ± 36.29 months vs. 15.5 ± 15.91 months; z = 2.327; p = 0.02) (Table 1).

VAS scores did not differ significantly (6.01 ± 2.41 vs. 5.63 ± 2.64; z = 1.229; p = 0.2192). SF-12 scores were lower in low back pain (SF-12P: 36.63 ± 10.99; SF-12M: 49.94 ± 11.06) than in foot/ankle disorders (SF-12P: 41.27 ± 11.40; SF-12M: 52.78 ± 9.01), with significant differences (SF-12P: z = −3.914; p = 0.0001; SF-12M: z = −2.474; p = 0.0134) (Table 2).

The mean CSI Part A score was higher in the low back pain group (31.82 ± 13.88) than in the foot/ankle group (25.20 ± 14.31) (z = 4.237; p = 0.000). However, the proportion of patients scoring >40 did not differ significantly (22.2% vs. 16.4%); Chi2 = 2.357; p = 0.125). No significant differences were found in CSI Part B (p = 0.752) (Table 2).

When patients were grouped by CSI Part A score (>40 vs. <40), those with higher scores included more women (73.86% vs. 54.42%; Chi2 = 10.6494; p = 0.001) and had a longer symptom duration (22.15 ± 16.24 vs. 20.15 ± 33.81 months; z = −1.98; p = 0.0477). Overall VAS scores were higher (6.7 ± 2.32 vs. 5.67 ± 2.51; z = −3.378; p = 0.0007). SF-12 scores were lower (SF-12P: 31.52 ± 11.26 vs. 40.9 ± 10.46; z = 6.67; p = 0.0000; SF-12M: 44.45 ± 11.94 vs. 53.01 ± 8.98; z = 5.971; p = 0.0000), and the number of comorbidities recorded in CSI Part B was significantly higher (p = 0.000).

Within the low back pain subgroup, patients with CSI > 40 showed higher ODI scores (36.26% ± 19.35 vs. 22.23% ± 13.82; z = −4.744; p = 0.0000) and higher lower-limb VAS scores (4.86 ± 2.63 vs. 3.4 ± 3.16; z = 2.677; p = 0.0074). Among patients with foot/ankle disorders, the FAAM score was significantly lower in those with CSI > 40 (61.03% ± 23.6 vs. 73.52% ± 20.43; z = 2.780; p = 0.0054), whereas the FAAM Sports score did not differ significantly (43.06% ± 25.97 vs. 54.6% ± 28.34; t = 1.9106; p = 0.0579).

Overall, these findings show that central sensitization, defined as CSI Part A > 40, is associated with higher pain intensity, poorer physical and mental health-related quality of life, greater functional disability in low back pain and reduced ability in daily living activities in foot and ankle disorders, as well as a higher burden of comorbidities, regardless of the anatomical origin of the musculoskeletal pain.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the presence and clinical correlates of central sensitization (CS) among patients consulting for low back pain (LBP) and foot and ankle pathologies. Using the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI), we observed that mean CSI Part A scores were significantly higher in patients with LBP compared with those with foot and ankle complaints, although no significant differences emerged in the proportion of individuals exceeding the cut-off threshold of 40 or in CSI Part B results. Furthermore, comparisons between patients above and below the CSI threshold revealed that higher CSI scores were associated with longer symptom duration, greater pain severity, higher disability indices, and lower quality-of-life measures. Importantly, we also identified sex- and age-related differences, with women and older individuals more likely to present with elevated CSI scores.

These findings add to a growing body of literature that has documented the role of CS in chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions, including LBP [8,10,18,19], carpal tunnel syndrome [14], frozen shoulder [20], and osteoarthritis [21]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore CS in foot and ankle pathologies, identifying a substantial prevalence and suggesting that CS may contribute to the chronicity and treatment response of these conditions in a similar way to other orthopedic presentations.

A notable aspect of our results is the discrepancy between mean CSI Part A scores and the proportion of positive cases defined by the ≥40 cut-off. While the LBP group demonstrated higher mean scores, no significant differences were found when categorizing patients by positivity. This raises important questions about the appropriateness of the threshold applied. In our study we adopted the cut-off of 40 as recommended by Neblett et al. [13], who validated the CSI in a sample of patients from an interdisciplinary pain clinic. However, this threshold may not be universally applicable to orthopedic populations. Indeed, when we applied a lower cut-off of 30, as used in prior studies [14], differences between groups reached statistical significance. This observation underscores the need for population-specific validation of the CSI and suggests that the 40-point criterion may be too restrictive in musculoskeletal settings.

The lack of significant findings for CSI Part B is consistent with previous reports. Mayer et al. [12] similarly found no differences between chronic LBP patients and controls in Part B, which documents the presence of central sensitivity syndromes. Our findings support the idea that Part B may be less sensitive to condition-specific variations than Part A, and that CS manifestations may not always co-occur with diagnosed comorbidities. Nevertheless, our observation that higher Part A scores correlated with a greater number of self-reported syndromes suggests that the two components are not entirely independent.

In terms of pain severity, no differences in VAS scores were observed between the LBP and foot/ankle groups. This result is expected, as the VAS captures subjective pain intensity regardless of anatomical location [22]. However, patients with elevated CSI scores consistently reported higher VAS values, both general and limb-specific, aligning with previous findings linking CS to enhanced pain perception [19,23]. This is consistent with the definition of CS as increased nociceptive sensitivity to normal or subthreshold stimuli [1,2].

Our study also highlights important demographic and clinical associations. LBP patients were older and had longer symptom duration than those with foot/ankle pathology, findings in line with the established age-related increase in LBP prevalence and severity [24,25]. Moreover, higher CSI scores were associated with older age, supporting Ramaswamy’s hypothesis that age-related changes in pain modulation may amplify central pain processing [26]. Similarly, female sex was more prevalent among patients with CSI ≥ 40, echoing prior work showing sex differences in pain processing and central modulation [27]. These findings underscore the importance of considering demographic factors when assessing the risk of CS in orthopedic populations.

In terms of disability and quality of life, our results reveal a consistent pattern: patients with higher CSI scores reported worse outcomes. The ODI was significantly higher in the high-CSI LBP subgroup, reflecting greater disability. This resonates with evidence from lumbar decompression surgery patients, where pre- and postoperative CSI scores correlated with ODI values and recovery trajectories [28]. Similarly, lower SF-12 physical and mental scores in the high-CSI group reflect the impact of CS on health-related quality of life, even though no prior studies have directly linked the SF-12 and CSI. The consistency of these associations reinforces the clinical relevance of CSI as a measure of disease burden.

Interestingly, we found that higher CSI scores were associated with worse scores on the FAAM for daily living activities, but not for sports activity. To date, no studies have examined links between the FAAM and CSI. The discrepancy may reflect differential functional demands: activities of daily living are universal, while sports activities are only applicable to a subset of patients. Thus, CSI may have a stronger association with basic daily limitations than with higher-level activities, particularly in older or less active populations. Further research is needed to clarify these relationships.

Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that CS plays an important role in musculoskeletal pain beyond the lumbar spine, extending to the foot and ankle. This is a novel contribution, as no prior studies have examined CS in foot/ankle patients. Identifying CS in this population has potential implications for prognosis and management. As suggested by prior research in other orthopedic conditions [14,19,20,21,22], CS may predict poorer response to conventional interventions and greater risk of chronicity. If confirmed in longitudinal studies, routine assessment of CS could guide individualized treatment strategies, such as integrating pain neuroscience education, graded exercise, and multimodal rehabilitation approaches targeting central mechanisms [3,5,7].

Regarding the pharmacotherapy on CSI, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as Duloxetine, have been shown to be effective in controlling pain, depression, anxiety and improving sleeping quality of patients [8]. Another group of drugs that have demonstrated efficacy are the serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Another key implication of our work concerns diagnostic thresholds. Our results indicate that reliance on a fixed CSI cut-off may obscure clinically meaningful differences between patient groups. This finding supports calls for population-specific validation of the CSI and careful interpretation of borderline scores [13]. Clinicians should be aware that even sub-threshold elevations in CSI may signify heightened central pain processing with functional consequences.

5. Limitations

Despite its strengths, including prospective data collection and the use of validated outcome measures [15,16,17,18,29], this study has several limitations that deserve consideration. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality. We cannot determine whether CS precedes symptom chronicity or arises as a consequence of persistent pain [30].

Second, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces potential recall and reporting bias. Although the instruments employed have demonstrated reliability and validity [12,15,16,17,18,29], subjective measures inevitably involve variability.

Third, generalizability is limited by the single-center setting. The sample was drawn from patients consulting at the University of Navarra Clinic, which may not reflect the demographic or clinical characteristics of patients in other institutions or health systems. Moreover, detailed information regarding the referral source and the pathway by which patients were included was not collected, limiting our ability to analyze clinical pathways and referral patterns.

Fourth, due to the lack of specific diagnostic data, we were unable to classify patients according to pain phenotypes, which restricts phenotype-based subgroup analyses. The choice of CSI cut-off remains a source of uncertainty. While we adhered to the widely used threshold of 40 points [13], our exploratory analyses suggest that alternative thresholds may yield different conclusions.

Fifth, data regarding the use of centrally acting pain-modulating medication was not collected. Medication history, including the use of drugs potentially influencing central sensitization (e.g., duloxetine, pregabalin, gabapentin), was not recorded, which may have influenced CSI scores. We recommend that future investigations include assessment of these pharmacotherapies to clarify their influence on central sensitization and patient outcomes.

Finally, objective physiological or neuroimaging markers of CS, such as quantitative sensory testing or functional imaging were not assessed. Including these could provide complementary evidence of central alterations [4,6,7].

6. Conclusions

Patients with low back pain exhibited higher CSI scores and a greater prevalence of central sensitization compared with those with foot and ankle disorders. Central sensitization is linked to greater pain, disability, and comorbidity. Early identification of central sensitization through routine screening is recommended, as multidisciplinary management strategies—combining education, rehabilitation, and pharmacotherapy—can optimize recovery and improve quality of life. These positive outcomes underscore the value of proactive screening and tailored interventions for affected patients.

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Pain central sensitization in patients consulting for low back pain and foot pathology, are there differences?” which was presented as a poster at Eurospine 2024 in Vienna 2–4 October 2024 [31].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L.-B., J.D.F., M.A.O.-G. and M.A.A.; methodology, R.L.-B., M.A.A. and C.S.M.; software, M.A.A.; formal analysis, R.L.-B., M.A.A.; investigation, M.A.A., N.M.G.; resources, R.L.-B., M.A.A.; data curation, M.A.A., N.M.G. and C.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.A., N.M.G. and C.S.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A., N.M.G. and R.L.-B.; visualization, M.A.A. and N.M.G.; supervision, R.L.-B., J.D.F., M.A.O.-G.; project administration, R.L.-B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and retrospectively using anonymized data. According to the regulations in place at our institution/country at the time the research began (Law 14/2007, of 3 July, on Biomedical Research (BOE No. 159, 4 July 2007); Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights; Royal Decree 957/2020, of 3 November, regulating observational studies with medicines for human use), this type of study did not require approval from an ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSP | Central Sensitization of pain |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| CUN | University Navarra Clinic |

| LBP | Low back pain |

| LL | Lower Limb |

| CLBP | Chronic low back pain |

| CSI | Central sensitization inventory |

| VAS | Visual analogue Scale |

| ODI | Oswestry disability index |

| SF-12 | 12-item Short Form Health Survey |

| FAAM | Foot and Ankle Ability Measure |

| SF-12M | 12-item Short Form Mental Health Survey |

| CS | Central sensitization |

References

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Morlion, B.; Perrot, S.; Dahan, A.; Dickenson, A.; Kress, H.G.; Wells, C.; Bouhassira, D.; Drewes, A.M. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitization across different chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, J.; Apeldoorn, A.; Hallegraeff, H.; Clark, J.; Smeets, R.; Malfliet, A.; Girbes, E.L.; De Kooning, M.; Ickmans, K. Low back pain: Guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 2015, 18, E333–E346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain 2009, 10, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Torres-Cueco, R.; van Wilgen, C.P.; Girbés, E.L.; Struyf, F.; Roussel, N.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; Daenen, L.; Kuppens, K.; Vanwerweeen, L.; et al. Applying modern pain neuroscience in clinical practice: Criteria for the classification of central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 2014, 17, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: Uncovering the relation between pain and plasticity. Anesthesiology 2007, 106, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; George, S.Z.; Clauw, D.J.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Kosek, E.; Ickmans, K.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Polli, A.; Kapreli, E.; Huysmans, E.; et al. Central sensitization in chronic pain conditions: Latest discoveries and their potential for precision medicine. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e383–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzarello, I.; Merlini, L.; Rosa, M.A.; Perrone, M.; Frugiuele, J.; Borghi, R.; Faldini, C. Central sensitization in chronic low back pain: A narrative review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2016, 29, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nopsopon, T.; Suputtitada, A.; Lertparinyaphorn, I.; Pongpirul, K. Nonoperative treatment for pain sensitization in patients with low back pain: Protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuttert, I.; Timmerman, H.; Petersen, K.K.; McPhee, M.E.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Reneman, M.F.; Wolff, A.P. Definition, assessment, and prevalence of central sensitization in patients with chronic low back pain: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, Y.; Connolly, M.; Srinivasan, A.; Kim, J.; Capizzano, A.A.; Moritani, T. Mechanisms and origins of spinal pain: From molecules to anatomy, with diagnostic clues and imaging findings. Radiographics 2020, 40, 1163–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.G.; Neblett, R.; Cohen, H.; Howard, K.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Williams, M.J.; Perez, Y.; Gatchel, R.J. Development and psychometric validation of the Central Sensitization Inventory. Pain Pract. 2012, 12, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R.; Cohen, H.; Choi, Y.; Hartzell, M.M.; Williams, M.; Mayer, T.G.; Gatchel, R.J. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI): Establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J. Pain 2013, 14, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Gong, C.; You, L.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ip, W.Y.; Wang, Y. Central sensitization in patients with chronic pain secondary to carpal tunnel syndrome and determinants. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 4353–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.L.; Irrgang, J.J.; Burdett, R.G.; Conti, S.F.; Van Swearingen, J.M. Evidence of validity for the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM). Foot Ankle Int. 2005, 26, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussel, N.A.; Nijs, J.; Meeus, M.; Mylius, V.; Fayt, C.; Oostendorp, R. Central sensitization and altered central pain processing in chronic low back pain: Fact or myth? Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, M.G.; Struyf, F.; Lluch Girbes, E.; Dueñas, L.; Verborgt, O.; Meeus, M. Autonomic nervous system function and central pain processing in people with frozen shoulder: A case-control study. Clin. J. Pain 2022, 38, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Fukushima, K.; Inoue, G.; Takaso, M. Mechanisms of peripheral and central sensitization in osteoarthritis pain. Cureus 2023, 15, e35446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Valente, M.A.; Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Jensen, M.P. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011, 152, 2399–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Koh, I.J.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, K.Y.; Kang, K.H.; In, Y. Central sensitization is associated with inferior patient-reported outcomes and increased osteotomy site pain in patients undergoing medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Medicina 2022, 58, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogon, I.; Takashima, H.; Morita, T.; Fukushi, R.; Takebayashi, T.; Teramoto, A. Association of central sensitization, visceral fat, and surgical outcomes in lumbar spinal stenosis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, N.; Emanski, E.; Knaub, M.A. Acute and chronic low back pain. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 98, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meucci, R.D.; Fassa, A.G.; Xavier Faria, N.M. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: Systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, S.; Wodehouse, T. Conditioned pain modulation—A comprehensive review. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2021, 51, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karshikoff, B.; Lekander, M.; Soop, A.; Lindstedt, F.; Ingvar, M.; Kosek, E.; Höglund, C.O.; Axelsson, J. Modality and sex differences in pain sensitivity during human endotoxemia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 46, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, T.; Iwata, E.; Nakajima, H.; Sada, T.; Tanaka, M.; Okuda, A.; Kawasaki, S.; Shigematsu, H.; Tanaka, Y. Central sensitization adversely affects quality of recovery following lumbar decompression surgery. J. Orthop. Sci. 2024, 29, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.; Layte, R.; Jenkinson, D.; Lawrence, K.; Petersen, S.; Paice, C.; Stradling, J. A shorter form health survey: Can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J. Public Health Med. 1997, 19, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković Vega, A.; Maguiña, J.L.; Soto, A.; Lama-Valdivia, J.; Correa López, L.E. Estudios transversales. Rev. Fac. Med. Humana 2021, 21, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart-Blanco, R.; Andrada, M.; Domenech-Fernández, J.; Alfonso, M.; Mateo, N. Pain central sensitization in patients consulting for low back pain and foot pathology, are there differences? Brain Spine 2024, 4 (Suppl. S2), 103067. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).