Definition

This report bridges fundamental ideas from introductory calculus to advanced concepts in quantum mechanics and nonlinear dynamics. Beginning with the behavior of second derivatives in oscillatory and exponential functions, it introduces the Airy equation and the WKB approximation as mathematical tools for describing wave propagation and quantum tunneling near turning points—locations where transitions between oscillatory and exponential components occur. The analysis then extends to the non-dissipative Lorenz model, whose double-well potential and solitary-wave (sech-type) solutions reveal a deep mathematical connection with the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Together, these examples highlight the universality of second-order differential equations in describing turning-point dynamics, encompassing physical phenomena ranging from quantum tunneling to coherent solitary-wave structures in fluid and atmospheric systems.

1. Introduction

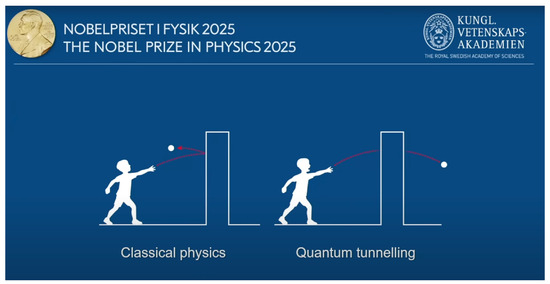

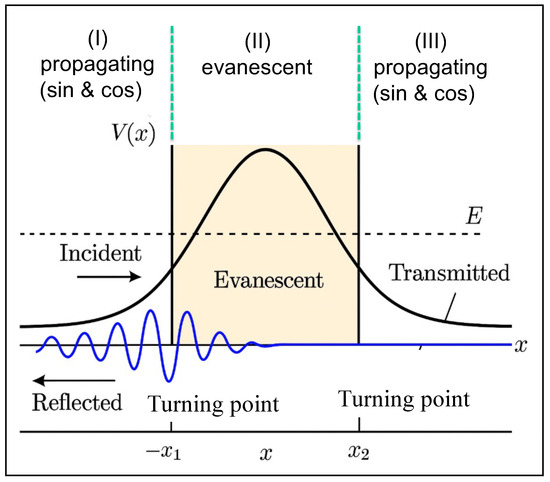

In 2025, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for pioneering research related to the phenomenon of quantum tunneling [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] (see Figure 1). Quantum tunneling describes how particles can traverse potential barriers that would be classically forbidden—a process central to nuclear fusion in stars [9,10], semiconductor devices [11], and scanning tunneling microscopy [12,13]. This remarkable discovery not only deepened our understanding of quantum mechanics but also inspired new perspectives on wave propagation and energy transfer across different physical systems. Figure 1 highlights the scientific importance of this concept.

Figure 1.

Quantum tunneling. The illustration is adapted from the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics press material, awarded for pioneering work on quantum tunneling, and is reproduced with permission. Credit: © Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences [7].

Originally derived from the Schrödinger equation, the phenomenon of tunneling can be described mathematically through the Airy equation [14,15] and the WKB (Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin) approximation ([14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]). These methods reveal how an oscillatory (propagating) solution transitions smoothly into an exponentially decaying (evanescent) solution near a turning point. The Airy equation provides a local model valid near the turning point, while the WKB method offers an asymptotic description of the same wave behavior away from it.

Beyond quantum mechanics, the same mathematical structures emerge in nonlinear systems. The nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation ([25]) and the non-dissipative Lorenz model ([26]) share strikingly similar amplitude equations that govern solitary waves and homoclinic orbits. This correspondence demonstrates the beauty of mathematical universality: the same second-order nonlinear differential forms that describe quantum tunneling also govern coherent wave structures in fluid dynamics and atmospheric models.

This report, therefore, explores how fundamental second-order differential equations connect seemingly different phenomena—the propagation of waves, quantum tunneling, and nonlinear solitary waves. Beginning from elementary calculus concepts, we trace a logical path from simple oscillations to complex nonlinear dynamics represented by the non-dissipative Lorenz model. The goals are twofold: (1) to help students who have completed Calculus I and II visualize the mathematical meaning of turning points and transitions between oscillatory and exponential behaviors, and (2) to show how similar mathematical structures appear across quantum mechanics, wave theory, and nonlinear dynamics.

This report is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the properties of second derivatives of the sine, cosine, and exponential functions to help first-year college students who have completed Calculus I and II understand the concepts of propagating and evanescent modes. Building on these introductory ideas, Section 3 demonstrates how a local analysis of the linear Schrödinger equation leads to the Airy equation, which contains a turning point where a transition between oscillatory and exponential components occurs. The corresponding and solutions of the Airy equation are presented, followed by an introduction to the WKB approximation. Section 4 discusses the non-dissipative Lorenz model, identifies two turning points in its structure, and establishes its relationship with the amplitude equation of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLS). A summary is provided at the end. Appendix A and Appendix B offer additional details on the analysis of phase and amplitude in the nonlinear and linear Schrödinger equations, respectively. Appendix C offers a concise overview of the non-dissipative Lorenz model. Appendix D discusses effective turning points of the non-dissipative Lorenz model.

2. Exploring Second Derivatives from a Calculus Perspective

Before studying differential equations, it is helpful to recall what a second derivative represents. The first derivative, , describes how fast a quantity changes, while the second derivative, , indicates how the rate of change itself varies. In Calculus III, where vector functions and their derivatives and integrals are discussed, if represents displacement, then its first and second derivatives correspond to velocity and acceleration, respectively. By examining a few familiar functions that appear in wave dynamics, we can already observe rich and contrasting behaviors that later lead to the concepts of propagating and evanescent solutions.

2.1. Second Derivatives of Sine and Cosine

Consider the sine and cosine functions that students first meet in Calculus I:

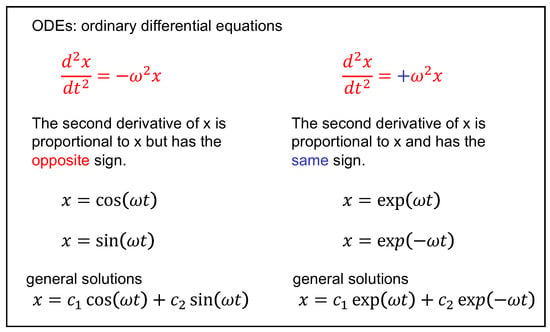

In both cases, the second derivative is proportional to the negative of the original function. This simple observation explains the repetitive, oscillatory nature of sine and cosine: whenever the curve bends downward, its rate of change reverses direction, producing continual motion back and forth. These relationships are summarized in Figure 2 under the label “”—a shorthand way to express that the acceleration (second derivative) is opposite in sign to the displacement.

Figure 2.

Illustration of second-derivative behavior. Sine and cosine have (), leading to oscillations, whereas exponential growth or decay has (). Red text highlights the oscillatory case where the second derivative has the opposite sign of the function while blue text highlights the exponential case where the second derivative has the same sign as the function. These two possibilities form the conceptual starting point for later discussions of propagating and evanescent solutions.

2.2. Second Derivatives of Exponential Growth and Decay

Now consider the exponential functions, and , introduced in Calculus II. Their second derivatives satisfy

Here, the second derivative has the same sign as the function itself. Such a relationship leads to a rapid increase or decrease rather than a periodic motion. The curves shown in Figure 2 “” illustrate how the acceleration reinforces (rather than opposes) the displacement, producing growth or decay instead of oscillation.

2.3. A Unified Mathematical Description

Both behaviors can be summarized by writing

where the constant determines the character of the motion:

- (a)

- (b)

2.4. A Note on Complex Numbers

To unify these two cases even further, mathematicians introduce complex numbers. By letting , the relation (1) with becomes equivalent to that for sine and cosine functions through Euler’s identity . The use of imaginary or complex variables thus allows one expression to describe both oscillatory and exponential behaviors. Students who continue to courses on complex variables or differential equations will see this idea developed systematically, forming the foundation for wave motion, quantum mechanics, and many physical applications.

3. Airy Equation and the Schrödinger Analogy

The preceding section presents simple second-order ODEs that exhibit either purely oscillatory or purely exponential behavior, corresponding to propagating and evanescent wave dynamics, respectively. However, in many physical systems, wave-like behavior changes character near a turning point—the location where motion transitions from an oscillatory (propagating) region to an exponential (evanescent) one. The Airy equation provides the simplest local model of this transition.

3.1. From the Schrödinger Equation to the Airy Equation

In the semiclassical (WKB) picture of the time-independent Schrödinger equation,

The quantity represents the local wave number and plays a role analogous to in Equation (1). Here, m denotes the particle mass, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant that characterizes the fundamental scale of quantum action, and E and represent the total and potential energy, respectively. A turning point occurs where , i.e., when the total energy equals the potential energy:

At this location, the nature of the solution changes: for () the wave solution oscillates, while for () it decays exponentially.

3.2. Linearizing the Potential near the Turning Point

To understand the local behavior near the turning point , we expand the potential linearly:

Substituting this into the definition of gives

where is a positive constant if . The Schrödinger Equation (2) then becomes

3.3. Rescaling to the Standard Airy Form

To simplify this expression, we introduce a dimensionless coordinate

which rescales the varying length scale near the turning point. In terms of X, Equation (5) reduces to the standard Airy equation

Its two independent solutions are the Airy functions and , which are discussed below.

3.4. Physical Interpretation

The Airy equation (Equation (6)) describes the smooth connection between oscillatory and exponential regions:

- For (corresponding to ), the solutions satisfy and are oscillatory, analogous to propagating waves.

- For (corresponding to ), the solutions satisfy and decay exponentially, representing the classically forbidden region.

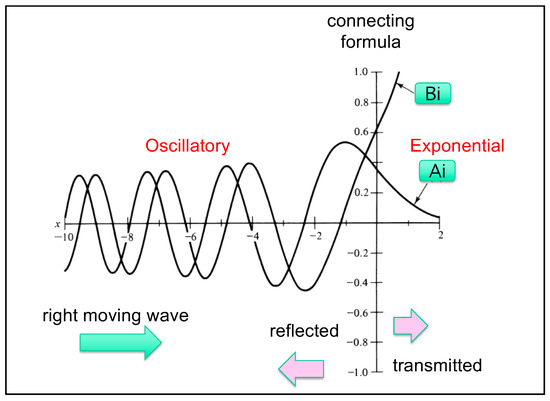

The boundary at represents the turning point. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Airy function decays for but oscillates for , making it the physically relevant solution for most tunneling problems. This mathematical structure captures the essence of quantum tunneling: a right-moving wave approaching a potential barrier can partially penetrate the region with , where the classical energy condition would otherwise forbid motion. Consequently, both reflected and transmitted components can be observed on opposite sides of the turning point.

Figure 3.

Physical interpretation of Airy functions across a turning point [27]. For the scaled Airy coordinate X (with the turning point at ): is oscillatory for (classically allowed) and decays for (forbidden), making it the physically relevant solution for tunneling problems; oscillates for but grows for , so it is typically excluded on the decaying side yet is useful in matching/connection formulas. An arrow indicates the direction of wave propagation. The oscillatory side can be decomposed into right-moving (incident) and left–moving (reflected) components, while the transmitted component resides in the exponential side ().

3.5. Review of the WKB (Liouville–Green) Method

The preceding discussions qualitatively illustrated the propagating and evanescent modes of solutions in the neighborhood of a turning point, where the equation reduces to the Airy form and the Airy functions provide the appropriate local approximation. To describe the solution behavior on the two sides of a turning point (but not at the turning point itself), the WKB method—named after Wentzel, Kramers, and Brillouin, and originally developed by Jeffreys—is often employed ([14,17,22]). A brief introduction is provided below.

The WKB method provides approximate solutions for linear second-order differential equations of the form ([22]):

where varies slowly compared with one oscillation or exponential length of the solution. This assumption is sometimes stated as

When is positive, the solution oscillates; when is negative, it decays exponentially. The WKB form unifies both behaviors.

3.5.1. Derivation Sketch

Following Mathews and Walker [22], we seek a solution of the form . Substituting into (7) and collecting terms yields

Assuming is small compared with (the slowly varying amplitude assumption), we obtain to leading order

and to next order . Combining the two gives the familiar WKB (or Liouville–Green) expression ([17]):

where and are constants.

3.5.2. Oscillatory and Evanescent Regions

- If , is real, and the solution is oscillatory (propagating waves).

- If , is imaginary, and the exponentials become real, giving decaying or growing (evanescent) behavior.

- The turning point occurs where and the two regimes meet. Near this point, the WKB form fails, and the equation must be approximated by the Airy equation as shown earlier.

3.5.3. Alternative Formulation and Notation

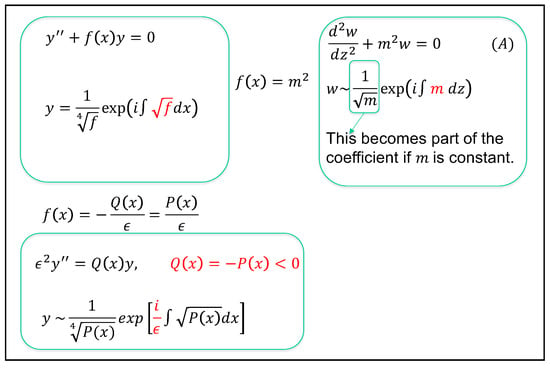

In physics texts, the equation is often written ([14])

with a small parameter and . The solution can then be expressed as

which emphasizes that the method is valid when varies slowly in space. This representation is consistent with the Liouville–Green form used in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Side-by-side presentations of the WKB method [27]. Left: the Liouville–Green form with the standard WKB amplitude/phase approximation . Right: the varying coefficient wave form , as compared to Equation (1), highlighting how and how the amplitude factor enters when m varies. Bottom: equivalent notations used in physics, with . Text in red highlights the coefficient of the linear term in all three ODEs, illustrating how this coefficient appears in different, but mathematically equivalent forms across the various WKB notations.

3.5.4. Connection Between the WKB and Airy Approaches

The WKB method provides an analytic bridge between the simple harmonic equation with constant frequency and variable-coefficient wave or Schrödinger equations. It is the natural asymptotic counterpart to the Airy-function treatment near a turning point. Together, the Airy and WKB approaches describe how waves propagate, attenuate, and reconnect across regions of varying barrier height or curvature.

4. The Non-Dissipative Lorenz Model and Solitary Waves

We now consider the nonlinear second-order ordinary differential equation

which may be viewed as a simplified form of the Duffing equation [26,28] or, equivalently, as the non-dissipative Lorenz model [26]. This equation can be derived from the Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC) system by neglecting the viscous and thermal diffusive terms, or from the classical Lorenz (1963) model [29,30,31] by removing the linear dissipative coefficients [32]. In the resulting system, the nonlinear energy transfer remains active, but the absence of dissipation leads to a conservative framework in which the total energy is preserved. The simplified coefficients in Equation (9) highlight the essential nonlinear restoring mechanism that allows the system to exhibit both oscillatory and exponentially decaying behaviors, depending on the solution amplitude. In the following sections, we establish the mathematical connection between the non-dissipative Lorenz model and the nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation. We then analyze the potential function associated with the non-dissipative Lorenz model and compare it with the typical scenario of a single potential barrier featuring two turning points.

- (a)

- Multiply by the derivative

Multiplying Equation (9) by gives

Recognizing that each term is the derivative of an energy-like quantity,

Equation (10) can be rewritten as a total derivative:

- (b)

- Integrate with respect to time

Integrating once with respect to t gives the first integral

where C is a constant of integration (the total energy). For the homoclinic solution, , so

4.1. Connection to the Nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) Equation

Equation (12) can be rewritten in the form

which is mathematically identical to the amplitude equation derived from the nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) framework discussed in Appendix A ([25,26]). The NLS equation, including its Gross–Pitaevskii form, has been widely applied to the study of Bose–Einstein condensation [33,34,35,36], as well as to water-wave dynamics and the classical Benjamin–Feir (modulational) instability [37,38,39,40,41]. The NLS equation plays a central role in the classical analysis of the Benjamin–Feir (modulational) instability. Related mechanisms of modulational instability have also been investigated in other dispersive-wave models, including Korteweg–de Vries (KdV)–type equations and full-dispersion shallow-water models [42]. In addition, the NLS equation and several of its variants have been employed in the study of chaotic dynamics and spatiotemporal complexity [43,44].

As shown in Appendix A, the amplitude equation associated with a traveling-wave solution of the NLS model takes the form

whose structure is identical to Equation (13) after a suitable rescaling of variables, including

Here, the variable in Equation (14) represents the spatial coordinate of the envelope function , while and determine the linear and nonlinear response coefficients.

4.2. Potential Function and Comparison with the Linear Schrödinger Case

In the linear Schrödinger equation, as briefly summarized in Appendix B, the relative strength of the potential function with respect to the energy E defines the energy landscape that determines whether a wave is propagating () or evanescent (), with the turning point marking the transition between the two regimes. In a similar spirit, the nonlinear equation of the non-dissipative Lorenz model admits an effective potential function that governs the evolution of . This analogy allows a direct comparison between the potential barrier in the Schrödinger case and the double-well potential in the Lorenz system, which is illustrated below.

Equation (9),

can be written in the form of a conservative system

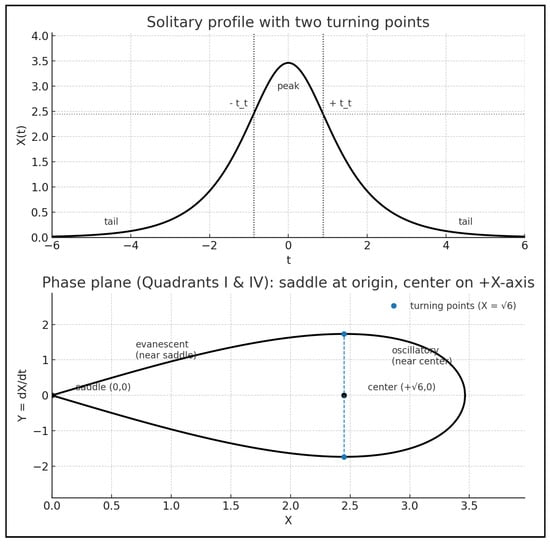

where the potential function is defined by

This potential has three stationary points (where ):

The equilibrium at corresponds to a local maximum of (a saddle in the phase plane), whereas the two symmetric equilibria at are local minima (centers). Thus, forms a symmetric double-well potential, shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Potential function associated with the non-dissipative Lorenz model (red). The maximum at (saddle) separates two minima at (centers). Regions near the minima correspond to oscillatory (propagating) behavior, whereas the central barrier region is evanescent. Mathematical equations for the full nonlinear, cubic-truncated, and linearized systems are presented in Appendix C.

It is important to distinguish between the potential energy introduced in the context of the linear Schrödinger equation and the potential function defined here for the non-dissipative Lorenz system. In the Schrödinger equation, is an externally prescribed function that shapes the energy landscape through which a wave propagates. In contrast, the potential in Equation (15) arises internally from the nonlinear dynamics of the system itself; it characterizes the self-consistent interaction of X and its derivatives. Thus, represents an external barrier or well that governs tunneling behavior, whereas serves as an effective potential describing the intrinsic structure of a nonlinear oscillator.

Physical interpretation

The motion of a particle in this potential mimics the behavior of the homoclinic orbit: it departs from the saddle at , oscillates within one well (), and returns to the saddle. The regions near the local minima (i.e., centers) represent propagating (oscillatory) states, while the vicinity of the barrier top near corresponds to an evanescent (exponential) region. As discussed in Appendix D, there exists a turning point between the saddle and either of the centers, where the effective coefficient of X changes sign. These interpretations are fully consistent with the analysis of turning points in the WKB and Airy-equation framework.

Comparison with the Linear Schrödinger Potential

Figure 6 presents the corresponding potential for the linear Schrödinger tunneling problem. In that case, the potential energy varies smoothly with a single barrier, producing three distinct regions:

| Region I (left, oscillatory) | Region II (barrier, evanescent) | Region III (right, oscillatory). |

The turning points occur where the total energy equals the potential, , marking the boundaries between oscillatory and exponential behavior.

Unlike the nonlinear potential (15) for the non-dissipative Lorenz model, the Schrödinger potential in Figure 6 contains no local minima. Its shape corresponds to a single barrier with two turning points, one on each side of the barrier crest. The double-well potential of the non-dissipative Lorenz system (Figure 5) therefore represents a nonlinear generalization of this concept: its two minima play roles analogous to Regions I and III in the quantum-mechanical tunneling problem, while the central barrier at serves as the evanescent region (Region II).

Figure 6.

Linear Schrödinger potential illustrating three regions and two turning points. Regions I and III are oscillatory, separated by the barrier region II, where the wavefunction decays exponentially (shaded in yellow). Unlike Figure 5, this potential lacks local minima and represents a single-barrier configuration.

- Figure 5 (nonlinear Lorenz potential): double-well structure with one central maximum and two local minima, supporting localized (homoclinic) oscillations.

- Figure 6 (linear Schrödinger potential): single-barrier structure without local minima, defining three regions separated by two turning points associated with quantum tunneling.

Although their geometries differ (with or without local minima), both potentials illustrate the same underlying principle: transitions between oscillatory (propagating) and exponential (evanescent) behaviors at turning points.

4.3. Solitary-Wave Solution

4.4. Physical Interpretation

The term in Equation (11) acts as a linear forcing, while represents the nonlinear restoring force. The interplay between these two terms permits a localized pulse that is oscillatory in its core and exponentially decaying in its tails. In the phase plane, the origin corresponds to a saddle associated with the evanescent tails, whereas the equilibria at are centers associated with oscillatory motion.

Figure 7.

Top: solitary profile . The levels mark the centers, defined by the condition . Bottom: corresponding phase-plane trajectory showing the saddle at and the centers at . Between the saddle at the origin and either center, the effective coefficient of X in the non-dissipative Lorenz model changes sign, defining an effective turning point (see Appendix D for details). These turning points play the same mathematical role as the turning point in the linear Schrödinger equation, separating oscillatory and evanescent-like regions of the solution. To compare the two panels, it is instructive to rotate the top panel by 90° clockwise: the propagating (oscillatory) components then appear at large , while the evanescent components occur near . The energy integral (11) mirrors the amplitude equation of the NLS form (14).

While Figure 5 and Figure 6 compare the potential-energy landscapes of nonlinear and linear systems, Figure 7 relates the potential in Figure 5 to the corresponding time-dependent solution of the non-dissipative Lorenz model. To compare the two figures geometrically, one may rotate the top panel of Figure 7 by clockwise: in this rotated view, the propagating (oscillatory) regions correspond to large X near the centers, whereas the evanescent region appears near the saddle where X is small. This visual correspondence reinforces the analogy between temporal evolution in the Lorenz system and spatial tunneling in the Schrödinger framework.

Connection to KdV-Type Equations

This study reviews the dynamics of the X–component of the non-dissipative Lorenz model (Appendix C) and its link to envelope equations, such as the NLS. As shown in [26], the Z–component of the non-dissipative Lorenz model is exactly equivalent to a KdV-type equation in a traveling-frame reduction. Its solitary-wave solution is the standard profile. For additional discussions of solitary-wave dynamics, see [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Connection to the Classical and Generalized Lorenz Models

In addition to solitary-wave solutions, the NLM also admits two types of oscillatory solutions [32]. By comparison, the classical dissipative Lorenz model produces three classes of solutions—steady states, limit cycles, and chaotic attractors—depending on the relative strengths of the heating and dissipative forcing [53,54,55]. A comparison between the non-dissipative and dissipative Lorenz models further shows that dissipation is essential for the emergence of a chaotic attractor. Moreover, by extending the nonlinear feedback loop of the classical Lorenz model [55], the inclusion of additional Fourier modes introduces extra nonlinear and dissipative terms, which can collectively provide aggregative negative feedback to stabilize solutions. Additional details can be found in [31,53,55].

5. Summary

This report has built a conceptual and mathematical bridge from fundamental calculus concepts to advanced topics in quantum and nonlinear dynamics. Beginning with the role of second derivatives in shaping oscillatory and exponential behaviors, the analysis showed how these elementary ideas evolve into the Airy and WKB formulations that govern wave propagation and tunneling near turning points.

The transition from linear to nonlinear systems reveals a deeper universality. The Airy equation captures how a wave passes smoothly from a propagating to an evanescent state, while the nonlinear, non-dissipative Lorenz model extends this idea to self-interacting systems with multiple equilibria. Its double-well potential exhibits turning points, centers, and saddles analogous to those in quantum tunneling, and its solitary (sech-type) solution demonstrates how localized oscillations can coexist with exponential tails.

By comparing the potential of the nonlinear, non-dissipative Lorenz model with the single-barrier potential of the linear Schrödinger equation, we recognized a unifying physical picture: both systems contain regions where the solution transitions between oscillatory (propagating) and exponential (evanescent) behavior, separated by turning points. Furthermore, the energy integral of the non-dissipative Lorenz model (Equation (13)) reproduces the amplitude equation of the nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation, linking localized solitary-wave dynamics with quantum dynamics through a common mathematical structure.

Together, these examples illustrate how simple mathematical principles—curvature, derivatives, and sign changes in the coefficients of second-order ordinary differential equations—reappear across scales and disciplines, from quantum tunneling to solitary waves in nonlinear fluids and atmospheric models. By connecting introductory calculus to modern physics and dynamical-systems theory, this study underscores the beauty of mathematical universality and its power to unify seemingly distinct physical phenomena.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to David Kuo, Pi-Gang Luan, and Mark Dunster for valuable discussions on quantum tunneling and turning points. He also thanks the students of Math 340 for their thoughtful feedback on the discussions presented in Section 2. Near the end of the manuscript, the author used the AI tool (manus) to verify the accuracy of several mathematical discussions. In particular, the AI-generated responses helped confirm the consistency of sign conventions in the Schrödinger equations—specifically, whether the coefficients appeared as or , and whether the phase factors were expressed as or .

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Connection Between the Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation and the Non-Dissipative Lorenz Equation

This appendix establishes a theoretical bridge between the amplitude equation derived from the nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation and the non-dissipative Lorenz model. By expressing the complex wave field of the NLS equation as the product of a slowly varying amplitude and a spatiotemporal oscillatory mode, one finds that the governing ordinary differential equation for the amplitude exhibits the same mathematical structure as the Lorenz-type equation discussed in Section 4. This connection highlights the shared mechanisms of self-modulation, dispersion–nonlinearity balance, and the emergence of solitary (sech-type) solutions that characterize both systems.

To demonstrate the universality of nonlinear wave equations, we consider the one-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation [14,25]:

which describes the slow evolution of weakly nonlinear dispersive waves. Here is a complex-valued wave function, and measures the strength of the nonlinear self-interaction. The NLS equation appears widely in quantum mechanics, nonlinear optics, and fluid dynamics, and serves as a canonical model for the formation of solitons.

Appendix A.1. Approach A: Spectral Representation

This approach demonstrates the limitations of single-mode analysis for connecting to amplitude equations; see discussion after Equation (A6).

By applying a spectral or separation-of-variables representation, we express the wave function as a product of an amplitude and a spatial mode:

where denotes the time-dependent amplitude, and is a normalized eigenfunction representing a spatial oscillation such as , , or .

Equations for the Amplitude

If the spatial mode satisfies the eigenvalue problem

then , we obtain

For the constant-modulus eigenmode , we have , yielding

which governs the complex amplitude .

What Equation (A5) actually implies.

Write with . Substituting this expression into (A5) and separating the real and imaginary parts yields

The time derivative of the phase, , represents the instantaneous (angular) frequency of the envelope. Equation (A6) shows that the frequency remains constant when the linear term () is considered. In the nonlinear case, also remains constant but is shifted by the nonlinear phase term .

Thus, the single spectral mode has a constant modulus and a nonlinearly rotating phase (self-phase modulation). Equation (A6) may be directly compared with the corresponding relation for the linear Schrödinger equation discussed in Appendix B, where the nonlinear term proportional to is absent.

However, it should be noted that the spectral method only yields phase dynamics. We cannot derive a second-order ODE for the amplitude from this approach. The connection to the Lorenz equation (which is second-order) cannot be established through this route.

Appendix A.2. Approach B: Traveling-Wave (Envelope) Reduction

Assume

The exponential factor represents a carrier wave with wavenumber k and carrier frequency , while the envelope function modulates the overall amplitude (and implicitly the phase) of the wave. Substituting into (A1) and separating real/imaginary parts gives the real amplitude ODE

For focusing nonlinearity (, i.e., ) and , the above equation has the same mathematical structure as the amplitude equation derived earlier from the non-dissipative Lorenz model [26], which admits localized (solitary) sech-type solutions.

Amplitude–phase formulation

To extend Equation (A7) to a complex envelope, let with . Substituting into Equation (A7) and separating the real and imaginary parts yield

The second equation integrates to , implying , where C is a real constant. Hence,

The first equation governs the envelope amplitude, while the second expresses the spatial phase gradient, , which represents a local wavenumber shift—a spatial analogue of the instantaneous frequency in the temporal formulation (Approach A). When , the envelope is purely real and Equation (A7) is recovered; when , the additional term introduces coupling between amplitude and phase, leading to spatially modulated (chirped) envelope solutions.

| Key Insight: |

| Single spectral modes (Approach A) exhibit only phase dynamics (self-phase modulation) (Equation (A6)) To obtain the amplitude dynamics that connect to the non-dissipative Lorenz model, we must consider spatially modulated envelopes (Approach B). This demonstrates why envelope equations (Equation (A7)) are essential for solitary-wave formation. |

Appendix A.3. Physical Interpretation

The correspondence between the NLS PDE (A1) and its amplitude ODE (A7) highlights a shared physical mechanism: both systems describe the evolution of a slowly modulated envelope that balances nonlinear self-interaction with dispersion. The NLS equation provides the complex-field description, while the amplitude equation (i.e., the non-dissipative Lorenz model) captures the underlying real-valued amplitude dynamics. This connection further emphasizes the mathematical unity among nonlinear wave equations, solitary waves, and coherent structures observed in fluid and atmospheric systems [14,17,26].

Appendix B. Linear Schrödinger Equation (with )

This appendix complements Appendix A by examining the linear Schrödinger equation with a nonzero potential term . In contrast to the nonlinear case, where the amplitude evolves according to a Lorenz-type equation, the linear formulation leads to constant-amplitude modes whose dynamics are governed solely by phase evolution. This comparison clarifies how the nonlinear self-modulation term in Appendix A alters the otherwise purely harmonic behavior of the linear system.

We consider the one-dimensional linear Schrödinger equation:

Appendix B.1. Approach A: Spectral Representation (General V(x))

Seek a separated field . Substituting into (A8) and dividing by gives

where the separation constant is independent of x. Hence,

Equivalently, writing with , we obtain the stationary second-order ODE:

Equations (A10) and (A11) are mathematically equivalent, both representing the stationary Schrödinger eigenvalue problem.

Amplitude–phase form for .

Let with . From (A9), we have , which gives

Thus, each separated mode possesses a constant amplitude and a purely oscillatory phase. When , Equation (A11) yields the free-particle dispersion relation , leading to

This result can be directly compared with Equation (A6) in Appendix A, where the additional term proportional to introduces a nonlinear phase modulation.

Appendix B.2. Approach B: Traveling-Wave (Envelope) Reduction

Consider the traveling-envelope ansatz

Differentiating gives

where primes denote . Substituting into (A8) and canceling yields

Separating real and imaginary parts (with h real) gives

Compatibility and physical interpretation

To admit a nontrivial envelope (), the imaginary part enforces

For the free Schrödinger dispersion , this yields in nondimensional units. The equality thus reflects the fact that the envelope travels at the group velocity of the carrier, not that speed and wavenumber are dimensionally identical.

Envelope equation

When is (A15) a true ODE in ?

In (A15), V remains a function of x. If is constant, then the equation becomes

However, if varies spatially, then with , introduces explicit time dependence unless V co-moves with the same velocity c. Hence, the traveling-wave reduction is valid only for constant (or co-moving) potentials; otherwise, the stationary separation method leading to (A11) is more appropriate. Note that the sign of in of Equations (A7) and (A15) is the same in the NLS (Appendix A) and linear Schrödinger (Appendix B) formulation.

Appendix B.3. Comparison of the Two Approaches

- For a general static potential , the separation ansatz leads to Equation (A11),which is an ordinary differential equation (ODE) in the spatial variable x.

- For a traveling-envelope reduction with a nontrivial envelope function , the condition must be satisfied, leading to Equation (A16),which represents an ODE in the co-moving coordinate only when V is constant or co-moving with the envelope.

The traveling-wave reduction is most naturally applied when V is either constant or co-moving with the wave. For general static potentials , the separation-of-variables approach (Approach A) is more appropriate.

| Potential Type | Best Approach | Resulting Equation |

| Either | ODE in or x | |

| static | Separation of variables | Stationary ODE in x |

| co-moving | Traveling-wave reduction | ODE in |

Appendix B.4. Linear vs. Nonlinear Regimes: The Role of δ and Turning Points

In the stationary form of the linear Schrödinger equation (where ), Equation (A11) can be expressed as

The sign of governs the qualitative behavior and changes at turning points where : for , solutions are oscillatory (propagating); for , they are exponential (evanescent).

| Region | Condition | Sign of | Behavior |

| I | Oscillatory (propagating) | ||

| II | Turning point | ||

| III | Exponential (evanescent) |

In the nonlinear (NLS/Lorenz-type) amplitude Equation (A7), a negative linear coefficient () can be balanced by the cubic term, producing a localized solitary wave (sech-type) with an oscillatory core and exponential tails. Thus, while implies evanescence in the linear problem, the nonlinear system supports coherent structures through a balance between dispersion and nonlinearity.

Concluding remark. Both the nonlinear NLS (Appendix A) and linear Schrödinger (Appendix B) equations admit spectral decompositions yielding constant-amplitude modes with phase dynamics. More generally, both linear and nonlinear Schrödinger formulations can be reduced to amplitude equations whose oscillatory or evanescent character directly corresponds to the turning-point dynamics discussed in the main text. In the linear Schrödinger equation in Equation (A11), changes sign across turning points, distinguishing propagating and evanescent regions. By contrast, in the nonlinear amplitude dynamics in Equation (A7), the linear tendency () is offset by the cubic nonlinearity, producing localized solitary waves consistent with the Lorenz-type model analyzed in Section 4.

Appendix C. The Non-Dissipative Lorenz Model

This appendix provides a brief review of how the non-dissipative Lorenz model (3D-NLM) can be derived from the two-dimensional (2D) Boussinesq equations for Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RBC) ([26,32,54]).

Appendix C.1. Governing Equations

The following 2D Boussinesq system is used as a starting point for deriving the non-dissipative Lorenz model and for computing the corresponding kinetic and potential energies:

Here, is the stream function such that and represent the horizontal and vertical velocity perturbations, respectively, and is the temperature perturbation. denotes the imposed temperature difference between the bottom and top boundaries. The constants g, , , and are the acceleration due to gravity, coefficient of thermal expansion, kinematic viscosity, and thermal diffusivity, respectively. The Jacobian of two functions is defined as

The crossed-out terms indicate neglected contributions in the dissipationless limit. These same equations, including the dissipative terms, were used by Lorenz (1963) [29,30,56].

Appendix C.2. Full and Non-Dissipative Lorenz Models

The dimensional reduction of the above system using the lowest Fourier modes yields the Lorenz three-mode system:

Here are the mode amplitudes, is the nondimensional time, is the Prandtl number, r is the normalized Rayleigh number (heating parameter), and b is a geometric constant associated with dissipation. Once again, the crossed-out terms denote the linear dissipative contributions that are omitted in the non-dissipative limit.

Appendix C.3. Energy Relation and the Non-Dissipative Form

Combining (A20) and (A22) (by multiplying (A20) by X and subtracting times (A22)) gives

which integrates to

where C is a constant representing a conserved quantity of the system.

Taking the time derivative of (A20) and adding (A21) yields

Substituting the conserved relation (A24) gives

This second-order equation is the non-dissipative Lorenz model, which represents a conservative nonlinear oscillator with both linear and cubic terms. After suitable rescaling of coefficients, it reduces to the canonical form used in the main text:

Appendix C.4. Connection to a Nonlinear Pendulum Equation

Here, I provide a brief introduction to the nonlinear pendulum equation and a short note on the stability of the unstable equilibrium point in the system, which yields the non-dissipative Lorenz model (NLM) as a reduced form.

Figure A1 displays a pendulum consisting of a weightless rod of length L with an attached bob of mass m. The opposite end of the rod is fixed at a support point located on a wall, which we take as the origin. The mass is free to oscillate or rotate, and its time-varying position is determined by the angle between the rod and the downward vertical direction. As shown in Figure A1, the angle is measured counterclockwise, so the natural hanging position corresponds to , while the inverted position with the mass vertically above the pivot corresponds to . These two positions are the lower (stable) and upper (unstable) equilibrium points, respectively.

Figure A1.

A pendulum consisting of a weightless rod of length L and a bob of mass m. The bob and the point of support are marked with a red and black dot, respectively. The parameter g denotes the gravitational force. The counterclockwise angle is measured from the downward vertical direction. Equilibrium points occur at (stable) and (unstable).

The time-varying angle of the nonlinear pendulum with a dissipative term is governed by

where k represents the damping (dissipative) coefficient. For the non-dissipative case (), the equilibrium points occur at (stable) and (unstable), where n is any integer.

A commonly used simplification is the linearized system near the stable equilibrium , obtained by replacing with :

For , this system corresponds to the simple harmonic oscillator illustrated on the left side of Figure 2.

Stability analysis of the unstable equilibrium

To examine the dynamics near the inverted position, we introduce a new variable

which shifts the unstable equilibrium to . Substituting this definition into Equation (A28) with yields

Using the Taylor expansion valid near , Equation (A30) becomes

Equation (A31) has the same mathematical structure as Equation (9) of the NLM and is also closely related to reduced forms of other physical models, including the inviscid Pedlosky model [57,58,59,60]. Stated alternatively, near the unstable equilibrium, the pendulum equation reduces to a cubic nonlinear oscillator. After rescaling time and amplitude, this reduced system becomes mathematically identical to the non-dissipative Lorenz model. The equivalence arises because both systems contain three terms and two independent scaling freedoms.

Appendix D. Effective Turning Points of the Non-Dissipative Lorenz Model

This appendix provides a concise overview of three complementary regimes within the non-dissipative Lorenz model, followed by a discussion of its effective turning points.

Appendix D.1. Three Complementary Regimes

The three cases collectively explain the evanescent tails, the oscillatory core, and the large-amplitude (nonlinear) behavior of the solitary pulse.

Scenario 1: Near the Trivial Equilibrium ()

Let with . Linearizing (9) gives

The general solution,

exhibits exponential growth/decay, consistent with a saddle at . This regime corresponds to evanescent behavior (non-oscillatory tails).

Scenario 2: Near the Nontrivial Equilibria ()

Let with . Substituting into (9) and retaining linear terms yields

For ,

whose solution

describes small oscillations about the centers with angular frequency . This regime captures the oscillatory core of the solitary structure.

Scenario 3: Large-Amplitude (Nonlinear) Regime

When is large, the cubic term dominates the linear term and (9) reduces to the leading-order balance

A consistent phase–amplitude representation is obtained by setting

which implies

Thus, satisfies the large-amplitude asymptotic equation. This regime characterizes the outer nonlinear envelope where the cubic restoring force dominates the dynamics.

Remark on Energetics

Multiplying (9) by and integrating gives the conserved energy form

The first term represents kinetic energy. The second and third terms, corresponding to the linear and cubic terms in (9), respectively, represent contributions to the effective potential energy. Scenario 1 corresponds to motion near the saddle of the effective potential, where the kinetic and linear terms dominate. Scenario 2 describes small oscillations near either potential minimum. Scenario 3 captures the asymptotic balance in which the kinetic and cubic terms dominate.

Appendix D.2. Potential–Curvature Viewpoint and Effective Turning Points

Although the non-dissipative Lorenz model does not explicitly contain a spatially varying coefficient, its potential function and corresponding restoring force vary continuously with X. Therefore, by considering the continuity of the local coefficients in the linearized form of the equation, we can identify a critical amplitude at which the system experiences a transition analogous to the classical turning point in the Airy equation. Below, this analogy is illustrated through an analysis of the curvature of the potential function.

We recast each model in the conservative form and identify the local curvature , which classifies equilibria and distinguishes regions of oscillatory (propagating) versus exponential (evanescent) behavior.

- (I)

- Linear unstable: X″ = X.Here , so . The origin is a local maximum of U (saddle in phase space), giving exponential behavior.

- (II)

- Linear stable: X″ = −X.Here , so . The origin is a local minimum (center), giving small–amplitude oscillations.

- (III)

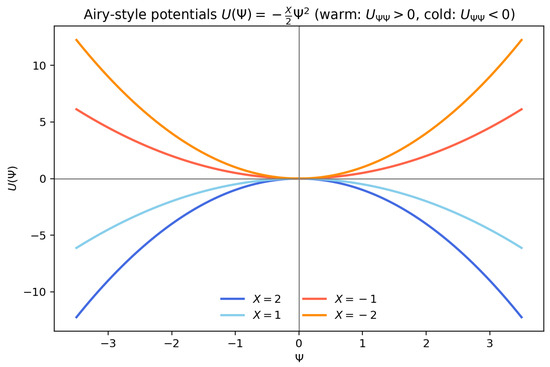

- The Airy Equation

Starting from the Airy equation, Equation (6), we may rewrite it in the conservative form , giving

Hence, the curvature changes sign with X: for , the potential is concave down (a local maximum), while for , it is concave up (a local minimum). Figure A2 illustrates for and .

Figure A2.

Airy-style potential in the U– space, written as . Warm colors () indicate positive curvature () corresponding to oscillatory (propagating) regimes, whereas cold colors () indicate negative curvature (), associated with evanescent (decaying) regimes. The curvature sign change thus marks the effective turning point in this dependent-variable representation.

- (IV)

- Non-dissipative Lorenz model

Starting from the non-dissipative Lorenz model, Equation (9) we

we obtain stationary points at , corresponding to a saddle and two centers. In contrast to the standard critical-point analysis, the present curvature analysis identifies the effective turning points as locations where the curvature of the potential vanishes, that is,

These points mark the boundaries between regions of positive and negative curvature in the potential function. Consequently, the two regimes are associated, respectively, with evanescent-like and oscillatory components in the phase-space sense. This curvature-based criterion provides an amplitude-space analogue of the Airy turning point, where a spatial coefficient changes sign.

Appendix D.3. Defining a Turning Point via the Curvature of the Potential Function

To clarify how a turning point can be understood in terms of the potential curvature, we examine a simple one-dimensional system governed by . By successively introducing (A) a linear oscillator with constant coefficients, (B) its derivation through linearization of a general potential about a reference point, and (C) the role of the curvature , we show that the vanishing of this curvature marks the transition between oscillatory () and evanescent () behaviors—that is, the definition of a turning point.

Part A. General Solution of a Shifted Linear Oscillator

Consider the ordinary differential equation

where a and b are constants. The associated homogeneous equation, , has characteristic roots , giving oscillatory or exponential behavior depending on .

Homogeneous solution.

Particular solution.

For , a constant satisfies the equation. For , direct integration yields .

General solution.

The constant term shifts the equilibrium position to and does not affect whether the motion is oscillatory () or evanescent ().

Part B. Linearization via Potential and Curvature at a Reference Point

Consider a conservative system

with potential function . Let be any reference point. Expanding F about gives

where and .

Define

Neglecting higher-order terms yields

which matches the form studied in Part A.

Interpretation.

The solution can be written as

Thus, represents the local curvature of the potential, and its sign determines whether the motion near is oscillatory (around a potential minimum) or evanescent (away from a potential maximum).

Part C. Turning Point Condition

From Parts A and B, the parameter determines the local character of the motion:

Therefore,

marks the transition between these two regimes. In this sense, (or ) corresponds to a turning point—the location where the potential curvature changes sign and the solution switches between oscillatory and evanescent behavior. To describe the detailed transition near such a point, higher-order terms (e.g., ) must be retained, leading to the familiar Airy-type connection between the two regions.

References

- Caldeira, A.O.; Leggett, A.J. Influence of Dissipation on Quantum Tunneling in Macroscopic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 46, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Cleland, A.N.; Devoret, M.H.; Esteve, D.; Martinis, J.M. Quantum Mechanics of a Macroscopic Variable: The Phase Difference of a Josephson Junction. Science 1988, 239, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devoret, M.H.; Martinis, J.M.; Clarke, J. Measurement of Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling out of a Zero-Voltage State of a Current-Biased Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 1908–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, J.B. The 1973 Nobel Prize for physics. Proc. IEEE 1974, 62, 823–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinis, J.M.; Devoret, M.H.; Clarke, J. Energy-Level Quantization in the Zero-Voltage State of a Current-Biased Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025—Popular Information. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/popular-information/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025—Popular Information. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2025/10/press-physicsprize2025-figure2.jpg (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Voss, R.F.; Webb, R.A. Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling in 1-µm Nb Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.A. Energy Production in Stars. Phys. Rev. 1939, 55, 103–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamow, G. Zur Quantentheorie des Atomkernes. Z. Für Phys. 1928, 51, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel Foundation. The Nobel Prize in Physics 1973. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1973/summary (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Binnig, G.; Rohrer, H. Scanning Tunneling Microscopy—From Birth to Adolescence. 1987. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/binnig-lecture.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986. 1986. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1986/summary (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Bender, C.M.; Orszag, S.A. Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers: Asymptotic Methods and Perturbation Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dunster, T.M. Simplified Airy function asymptotic expansions for reverse generalised Bessel polynomials. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. La mécanique ondulatoire de Schrödinger: Une méthode générale de resolution par approximations successives. Comptes Rendus L’AcadéMie Sci. 1926, 183, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.E. Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics, 1st ed.; International Geophysics Series; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Green, G. On the motion of waves in a variable canal of small depth and width. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1837, 6, 457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kramers, H.A. Wellenmechanik und halbzahlige Quantisierung. Z. Für Phys. 1926, 39, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, 3rd ed.; Course of Theoretical Physics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1977; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Liouville, J. Sur le développement des fonctions et séries. J. Mathématiques Pures Appliquées 1837, 1, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J.; Walker, R.L. Mathematical Methods of Physics, 2nd ed.; Addison–Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, G. Eine Verallgemeinerung der Quantenbedingungen für die Zwecke der Wellenmechanik. Z. Für Phys. 1926, 38, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, R. Applied Partial Differential Equations with Fourier Series and Boundary Value Problems, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2013; p. 756. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.-W. Homoclinic Orbits and Solitary Waves within the Non-dissipative Lorenz Model and KdV Equation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W. Lecture Notes on the WKB Method; Math 537: Ordinary Differential Equations, Fall 2020; San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.; Devaney, R.L.; Hall, G.R. Differential Equations (with CD-ROM), 3rd ed.; Brooks/Cole: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. The Essence of Chaos; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993; p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.-W. A Review of Lorenz’s Models from 1960 to 2008. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2023, 33, 2330024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W. On periodic solutions in the non-dissipative Lorenz model: The role of the nonlinear feedback loop. Tellus A 2018, 70, 1471912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalfovo, F.; Giorgini, S.; Pitaevskii, L.P.; Stringari, S. Theory of Bose–Einstein condensation in trapped gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, 463–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, L. Nonlinear Schrödinger Equations for Bose–Einstein Condensates. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.01921. [Google Scholar]

- Pitaevskii, L.; Stringari, S. Bose–Einstein Condensation and Superfluidity; International Series of Monographs on Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pitaevskii, L.; Stringari, S. Bose–Einstein Condensation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, D.; Stuhlmeier, R. The nonlinear Benjamin–Feir instability: Hamiltonian dynamics, discrete breathers and steady solutions. J. Fluid Mech. 2023, 958, A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, T.B.; Feir, J.E. The disintegration of wave trains on deep water. Part 1: Theory. J. Fluid Mech. 1967, 27, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleewong, M.; Grimshaw, R. Examination of the effect of wind drift on water wave packets in the forced nonlinear Schrödinger equation. J. Ocean. Eng. Mar. Energy 2025, 11, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.R. Nonlinear water wave equations. In Nonlinear Ocean Waves and the Inverse Scattering Transform; International Geophysics; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 97, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.E. Stability of periodic waves of finite amplitude on the surface of a deep fluid. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 1968, 9, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronski, J.C.; Hur, V.M.; Johnson, M.A. Modulational Instability in Equations of KdV Type. In New Approaches to Nonlinear Waves; Tobisch, E., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablowitz, M.J.; Herbst, B.M.; Schober, C.M. Computational chaos in the nonlinear Schrödinger equation without homoclinic crossings. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1996, 228, 212–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlizerman, E.; Rom-Kedar, V. Three types of chaos in the forced nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mandi, L.; Chatterjee, P. Effect of externally applied periodic force on ion acoustic waves in superthermal plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 042112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamarion, M.V.; Pelinovsky, E. Interaction of interfacial waves with an external force: The Benjamin–Ono equation framework. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamarion, M.V.; Pelinovsky, E. Interactions of solitons with an external force field: Exploring the Schamel equation framework. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, R.; Pelinovsky, E. Interaction of a solitary wave with an external force in the extended Korteweg–de Vries equation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2002, 12, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, R.; Pelinovsky, E.; Sakov, P. Interaction of a solitary wave with an external force moving with variable speed. Stud. Appl. Math. 1996, 97, 235–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, R.; Pelinovsky, E.; Tian, X. Interaction of a solitary wave with an external force. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1994, 77, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovsky, L.; Pelinovsky, E.; Shrira, V.; Stepanyants, Y. Localized wave structures: Solitons and beyond. Chaos 2024, 34, 062101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxson, W.; Shen, B.-W. A KdV-SIR Equation and Its Analytical Solutions for Solitary Epidemic Waves. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2022, 32, 2250199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Zeng, X. 50th Anniversary of the Metaphorical Butterfly Effect since Lorenz (1972): Special Issue on Multistability, Multiscale Predictability, and Sensitivity in Numerical Models. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Zeng, X. One Saddle Point and Two Types of Sensitivities Within the Lorenz 1963 and 1969 Models. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.-W. Aggregated Negative Feedback in a Generalized Lorenz Model. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2019, 29, 1950037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, B. Finite amplitude free convection as an initial value problem. J. Atmos. Sci. 1962, 19, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedlosky, J. Finite-amplitude baroclinic waves with small dissipation. J. Atmos. Sci. 1971, 28, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedlosky, J. Limit cycles and unstable baroclinic waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 1972, 29, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedlosky, J. Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 710. [Google Scholar]

- Pedlosky, J.; Frenzen, C. Chaotic and periodic behavior of finite-amplitude baroclinic waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 1980, 37, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).