Definition

Cochlear implants (CIs), a revolutionary breakthrough in auditory technology, have profoundly impacted the lives of individuals with severe hearing impairment. Surgically implanted behind the ear and within the delicate cochlea, these devices represent a direct pathway to restoring the sense of hearing. Implanting hope alongside innovation, their captivating history unfolds through pivotal dates and transformative milestones. From the first human implantation by Drs. William House and John Doyle in 1961 to FDA approval in 1984, each step in their evolution mirrors a triumph of human ingenuity. The 1990s witnessed significant miniaturization, enhancing accessibility, while the 21st century brought about improvements in speech processing and electrode technology. These strides have elevated CIs beyond functional devices to life-changing instruments, enriching both auditory experiences and communication skills. This entry delves into the captivating history of CIs, spotlighting key dates that paint a vivid picture of challenges overcome and remarkable progress achieved. It explores the people and moments that defined their development, ultimately shaping these implants into indispensable tools that continually redefine the landscape of hearing assistance.

1. Introduction

Cochlear implants (CIs) represent a significant advancement in auditory rehabilitation, offering a pioneering solution for individuals with severe hearing impairment.

These sophisticated electronic devices, surgically implanted with precision, aim to restore the sense of hearing by directly stimulating the auditory nerve [1]. Comprising external and internal components, the device is intricately engineered to rest discreetly behind the ear, while the internal element finds its purpose within the cochlea—a delicate, spiral-shaped cavity nestled in the inner ear. The external setup consists of a microphone, sound processor, and transmission system, while the internal device consists of a receiver/stimulator and an electrode array.

In brief, the external microphone captures environmental sound or speech, sending the information to the sound processor. The speech processor converts mechanical vibrations (sound) into an electric signal, which is wirelessly transmitted through the skin via radio frequency to the internal receiver/stimulator. The receiver/stimulator then directs the electrical signal to the cochlea’s electrode array, stimulating the auditory nerve and allowing the signal to travel along the auditory pathway to the auditory cortex in the brain [2]. In the continuum of technological progress, CIs have evolved into indispensable instruments, acting not only as adept conductors of auditory restoration but also as pivotal tools in enhancing communication skills. This technological development goes beyond its initial purpose, improving the overall quality of life for those contending with profound hearing challenges.

This manuscript endeavors to delve into the historical evolution of CIs, tracing their development from conceptualization to the cutting-edge devices we recognize today. By presenting a chronological narrative, we seek to highlight key milestones, technological advancements, and societal implications that have shaped the trajectory of CI innovation. Through this exploration, we strive to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the historical context surrounding CIs, shedding light on the challenges overcome and the triumphs achieved in the journey towards enabling individuals with hearing impairment to experience the world of sound.

2. Early Developments: Alessandro Volta’s Groundbreaking Exploration into Harnessing Electricity for Auditory Perception

The Leyden jar, invented in 1745, significantly advanced the medical use of electricity. Benjamin Wilson detailed extra-auricular electrical stimulation in 1748, applying an electrified vial to a deafened woman’s left temple. Although subsequent repetitions improved her hearing, attempts on six other deaf individuals were unsuccessful [3].

Alessandro Volta, renowned for inventing the voltaic pile, the first chemical battery, made a pioneering contribution to the exploration of electricity’s auditory potential. In the early 1800s, he devised an experiment where he connected each pole of a battery to a metal probe. Intriguingly, Volta inserted one probe into one of his ear canals and the other into the opposite canal. Notably, one of the probes featured a switch that could interrupt or allow the flow of current. Upon closing the switch, he recounted the resulting sensation as a “jolt in the head”, accompanied by a sound reminiscent of “crackling, jerking, or bubbling, as if some dough or thick material was boiling” [4]. This laid the groundwork for future developments like CIs.

In 1855, Duchenne de Boulogne experimented with cochlear stimulation using alternating current, experiencing sensations of buzzing, hissing, and ringing. The stimulation also triggered non-auditory sensations, including a metallic taste [5]. In 1905, the American La Forest Potter patented an electrical stimulating system for the mastoid bone, describing improvements in passing electric current through mastoid bones and natural ear passages, as well as transmitting phonetic excitement through an electric current [6]. By 1930, Ernst Glen Wever and Charles Bray observed that amplifying the output from an electrode intracranially in a cat’s acoustic nerve replicated speech waveforms in both frequency and amplitude [7]. The first direct evidence of electric stimulation affecting the auditory nerve in humans, however, was provided by a group of Russian scientists. They reported that electric stimulation resulted in a sensation of hearing in a deaf patient with damage to both the middle and inner ears [8].

In 1939, the Bell Labs researcher Homer Dudley introduced the vocoder, a real-time voice synthesizer. It extracted speech components using 10 bandpass filters, condensing speech into fundamental frequency, spectral intensity, and overall power [9]. The vocoder’s principles influenced early speech processing for multichannel CIs. In 1940, the Americans Clark Jones, Stanley Smith Stevens, and Moses Lurie inserted electrodes directly into the middle ears of 20 patients without tympanic membranes. Most had undergone mastoid operations [10]. This proximity to the inner ear, producing sounds, led to the hypothesis that direct stimulation of the auditory nerve could result in hearing.

3. Post-World War II Advances

3.1. Electronics, Auditory Nerve Stimulation Experiments, and the Emergence of Multichannel Cochlear Implants with Silicon Technology Impact

In 1950, the Swedish neurosurgeon Lundberg conducted a neurosurgical operation where he stimulated a patient’s auditory nerve with a sinusoidal electric current. A surprising finding was that the sinusoidal current was perceived not as a tone but as a noise [11].

The French team of André Djourno and Charles Eyriès is often credited as early pioneers of cochlear implantation. During facial nerve graft surgery on a patient with prior cholesteatoma-related temporal bone resection, they observed a small segment of the VIII nerve. On 25 February 1957, they cautiously placed an electrode on the accessible vestibular nerve segment. Dr. Eyriès hesitated due to extensive damage but proceeded, implanting a 2.5 cm induction device. Despite not mentioning the cochlea, Djourno and Eyriès are acknowledged for their groundbreaking intra-auricular electrode implantation, foreseeing the future development of the CI. Their studies, though short-lived, gained wide recognition through their publication in La Presse Médicale [12]. The news spread beyond France, reaching the Los Angeles Times. A patient at Dr. William House’s clinic shared the article, leading Dr. House to explore further. Convinced by the insights, he aimed to develop a reliable auditory prosthesis for the deaf.

In 1961, Drs. House and Doyle pioneered CIs by implanting gold-insulated electrodes in two deaf patients in Los Angeles. Dr. House, an otology specialist, collaborated with Dr. Doyle, a neurosurgeon, to develop the initial implants featuring either a single wire with a flamed ball contact or an array of five electrodes. Their surgical approach involved inserting the electrode(s) into the scala tympani through an incision in the round window membrane [13]. Despite early success, including basic frequency discrimination and word identification in closed sets, complications arose due to the insufficient biocompatibility of the electrodes, leading to their removal and limiting long-term testing. Concerns about infection and electrode rejection prompted a temporary pause in Dr. House’s work on the implant. Dr. House’s interest in CIs was reignited, as he observed successes with other medical devices. Collaborating with the electrical engineer Mr. Urban, they developed the first CI system usable outside the laboratory, marking a significant milestone in the history of CIs. This achievement solidified Dr. House’s status as the widely recognized “father” of CIs.

In 1966, Simmons implanted single-wire electrodes in a deaf-blind volunteer’s modiolus, distinct from scala tympani implants [14]. Basic studies showed pitch variations with electrode or rate changes. Speech signals produced speech-like percepts, but comprehension was limited. Simmons, disappointed, ceased human studies, turning to animal research for broader physiological insights and safety evaluation. In the early 1970s, a University of California, San Francisco team, led by Michelson and Merzenich, explored single-electrode implants. Initial trials showed limited speech recognition, but Merzenich’s animal experiments demonstrated time-locked neural responses for frequencies up to 600 Hz [15]. Further studies aimed to develop CI systems with multiple stimulation sites to represent frequencies above 600 Hz.

In 1975, at the Technical University of Vienna, Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair initiated CI development with the goal of designing an electronic implant for both hearing sounds and understanding speech. Their CI, successfully implanted at the University Clinic in Vienna by Prof. Kurt Burian on 16 December 1977, marked a significant achievement [16]. Simultaneously, at the University of Pittsburgh, Bilger and colleagues assessed the speech performance of single-electrode CI recipients [17]. Despite assisting in recognizing environmental sounds, open-set speech recognition remained challenging. During a controversial period for CIs, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) commissioned a study led by Dr. Robert C. Bilger. The study included all 13 U.S.-implanted patients at that time, using early single-site stimulation devices. The “Bilger Report” demonstrated significant quality-of-life improvements, reshaping perceptions at the NIH and among experts. The study marked a pivotal moment, granting respectability to CIs in medical and scientific communities, leading to increased NIH support for CI research and development from 1978.

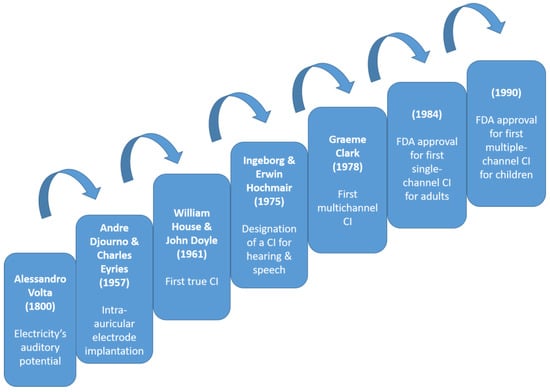

In 1978, Graeme Clark achieved a milestone with the first contemporary multichannel CI, restoring hearing in a post-lingual deaf adult [18]. Between the 1970s and 1990s, CI technology advanced significantly, surpassing 1000 surgeries. The first “successful” single-channel cochlear implantation occurred in 1972, with notable improvements in speech perception in the mid-1980s. However, it did not fully replicate normal neural activity. By 1984, the 3M/House single-electrode CI gained FDA approval [19]. In the 1990s, advancements in speech processing technology propelled CIs into mainstream medicine, significantly improving patients’ quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of cochlear implant evolution over time highlighting key milestones as steps on a ladder, each serving as a leap to the next stage [4,12,13,16,18,19,20].

The utilization of silicon-based materials has facilitated the creation of smaller, more intricate components, contributing to the development of compact and highly sophisticated CI processors. The integration of silicon microchips has significantly enhanced signal processing capabilities, resulting in improved sound quality and heightened precision in auditory stimulation. Moreover, the biocompatibility of silicon materials ensures compatibility with the human body. As silicon technology continues to advance, its ongoing impact on implant design holds promise for further innovations.

Significant challenges in CI development include refining speech processing algorithms to enhance sound perception, improving battery life, and addressing issues related to device durability and long-term reliability. Additionally, challenges arise in optimizing outcomes for specific patient populations, such as children and individuals with residual hearing. Overcoming these challenges requires ongoing research, technological advancements, and collaboration between clinicians, researchers, and CI manufacturers. Continuous innovation, combined with rigorous testing and regulatory approval processes, ensures the continued improvement and accessibility of CIs for individuals with hearing impairment.

3.2. Limited Success and Ethical Dilemmas: Scientists’ Perspectives on First Cochlear Implants

In the early stages, CIs faced skepticism and scrutiny within the scientific community, a common reaction to most emerging technologies. Many auditory scientists and otologists criticized these implants, rejecting the potential for restoring useful hearing due to perceived crude stimulation patterns [21]. Dr. Merle Lawrence expressed doubt, asserting the impossibility of stimulating auditory nerve fibers for speech perception [22]. Despite initial skepticism, pioneers persevered, laying the groundwork for today’s advanced CI devices. Over time, attitudes shifted, with Gifford and her team reporting in 2008 that over a quarter of CI patients achieved perfect scores in sentence recognition tests [23]. As CIs advanced, standard audiological tests became inadequate for assessing speech understanding deficits.

4. Expanding Applications and Technological Advances (1990s–2000s)

Undoubtedly, there is considerable variability and individual differences in speech and language outcomes among deaf children and adults who have undergone cochlear implantation. Indeed, some studies report that, for many CI users, speech communication continues to be challenging and effortful, especially in everyday, real-world listening conditions [24].

4.1. Pediatric Cochlear Implantation

The FDA first approved the use of CIs in children at least 2 years old in 1990, and lowered the minimum age to 12 months in 2000. Research developments and technological improvements provided the foundation to approve lowering the indication to 9 months [20]. Pediatric cochlear implantation is pivotal for children with hearing impairment, particularly when performed early in life. Early intervention, typically within the first few years, maximizes developmental benefits by capitalizing on the critical stages of auditory system maturation during early childhood. Research consistently shows that early cochlear implantation fosters significant progress in communication, language acquisition, and overall cognitive development. By providing access to auditory input during this sensitive period, children can establish neural pathways for effective auditory processing, facilitating age-appropriate language milestones and enhancing social integration.

4.2. Bilateral Cochlear Implants

Recent studies underscore the increasing adoption of bilateral cochlear implantation, unveiling a spectrum of benefits such as enhanced binaural summation and a notable surge in speech recognition, especially in noisy environments, outperforming the capabilities of unilateral implants [25]. In the midst of ongoing debates on cost-effectiveness, bilateral CIs are steadily solidifying their status as the standard treatment for individuals with bilateral profound sensorineural deafness.

This innovative paradigm in cochlear implantation yields a multitude of advantages. It goes beyond merely improving speech comprehension in challenging auditory environments; it significantly elevates sound localization capabilities. Moreover, it rectifies the asymmetry inherent in unilateral solutions, providing a more equitable representation of auditory input. By delivering stimulation to both ears, bilateral cochlear implantation optimally exploits the advantages of binaural hearing [26]. This not only heightens spatial awareness but also enhances the ability to discriminate between diverse sounds, enriching the overall auditory experience for recipients.

Bilateral cochlear implantation, whether executed simultaneously or sequentially, offers numerous potential advantages, yet there may be a few associated drawbacks. Initial concerns about postoperative balance function, anesthesia duration, and cost-effectiveness in simultaneous procedures have been mitigated by studies in children and infants, establishing their safety. Sequential bilateral cochlear implantation is highly advisable for unilaterally implanted children with limited residual hearing or poor discrimination skills in the opposite ear. Decisions should be individualized, and although a short inter-implant delay and lower age at the second surgery are preferable, benefits can still be realized even with delayed procedures. Older age at the second implant or extended inter-implant delays do not necessarily negate the potential advantages of bilateral electrical stimulation [27]. While simultaneous procedures have been shown to be advantageous and resource-efficient in children, comprehensive data on adults remain limited. Adults with bilateral hearing loss often favor a sequential approach, beginning with the worse ear.

4.3. Cochlear Implant Processing: Guiding Auditory Perception and Enhancing Speech Recognition

Navigating the intricacies of signal processing can pose a challenge for individuals without specialized training in this complex and technical field. In this manuscript, we elected to avoid analytical signal processing details, which have been thoroughly analyzed in other reports [28]. However, it is essential to note that the ultimate and potentially decisive distinction among implant devices lies in the chosen signal processing strategy responsible for transforming the speech signal into electrical stimuli. Over the past 25 years, a spectrum of techniques has emerged, some emphasizing waveform preservation and others giving priority to envelope or spectral features, such as formants.

Modern CIs employ advanced sound processing, utilizing algorithms like “Continuous Interleaved Sampling” to mimic the auditory system’s filtering function. Through pre-emphasis to enhance high frequencies, the digitized sound is filtered through a set of filters corresponding to intracochlear electrodes. These electrodes deliver modulated electrical pulses, simulating the behavior of hair cells.

In tandem, advancements in speech processing research have paralleled evolving implant designs, emphasizing the effective translation of sound stimuli into neural codes for improved speech recognition [29]. CI processors, driven by fast microprocessors, have transitioned from single-electrode to multiple-electrode configurations along the basilar membrane. Modern processors utilize bandpass filters to segregate the sound spectrum and implement automatic gain control to manage sound intensities before applying them to corresponding electrodes. The continuous evolution of CI technology aims to refine speech discrimination and enhance the perception of diverse sound types, including music.

5. Beyond Auditory Restoration

5.1. Cochlear Implants for Single-Sided Deafness and Tinnitus

CIs have evolved beyond their initial purpose of restoring hearing, expanding their capabilities to address challenges beyond bilateral hearing loss. This broader application now includes individuals with single-sided deafness (SSD) and those with persistent tinnitus. For individuals with SSD, characterized by profound hearing loss in one ear while the other remains unaffected, CIs present a remarkable solution. Moreover, CIs have shown promise in managing tinnitus, a condition characterized by the perception of noise in the absence of external stimuli. Through the strategic electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve, CIs have demonstrated the potential to mitigate the symptoms of tinnitus, providing relief for those plagued by persistent ringing or buzzing sounds [30].

In the realm of SSD, adults encounter challenges encompassing compromised sound source localization, diminished speech understanding in noisy environments, and the distressing presence of tinnitus [31]. Existing non-invasive interventions, such as contralateral routing of signal (CROS) and bone conduction devices (BCDs), aim to address these issues but are associated with limitations [32,33]. Cochlear implantation emerges as a highly effective alternative, showcasing superiority by significantly enhancing sound localization, improving speech understanding, and enhancing the overall quality of life for both adults and pediatric patients with SSD.

5.2. Cochlear Implant Innovations in Music Perception

The intersection of CIs and music perception poses significant challenges due to the complex nature of musical elements such as pitch, melody, rhythm, and timbre. Early CI users reported difficulties in discerning and appreciating music, highlighting limitations in both technology and understanding. Nevertheless, technological progress has evolved the landscape over the years. Modern CI designs, sophisticated signal processing algorithms, and improved electrode arrays have substantially enhanced the music perception capabilities of individuals with CIs [34]. Current research and contemporary insights suggest notable improvements in musical experiences for CI users, with rehabilitation programs playing a crucial role in refining their ability to engage with and enjoy music. Therefore, it is not surprising to see CI users playing a musical instrument [35]. While challenges persist, ongoing efforts in research and innovation continue, attempting to connect CIs with the world of music, offering promising prospects for the future.

5.3. Advances in Hybrid Devices

Recent advances in the field of auditory prosthetics have brought about notable developments in hybrid devices, significantly improving the options available for individuals with hearing impairment. Hybrid devices represent another innovative frontier, blending traditional CI technology with acoustic amplification for individuals with partial hearing loss. These devices combine electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve with natural acoustic input, catering to individuals who may have residual low-frequency hearing [36]. Hybrid implants aim to preserve any remaining natural hearing while providing the necessary electrical stimulation for higher-frequency sounds, resulting in a more natural and comprehensive auditory experience. Advancements in signal processing algorithms and electrode array designs have further refined the performance of implantation and hybrid devices. These innovations focus on optimizing the synchronization of signals from both implants and tailoring the stimulation patterns to individual hearing profiles, thereby maximizing the benefits of these technologies. These advances signify a significant step forward, offering individuals with hearing impairment more personalized and effective solutions.

6. Social Impact and Ethical Considerations

6.1. Deaf Culture and the Deaf Community’s Response to Cochlear Implants

The Deaf community is a vibrant group with its own language and traditions, rooted in the shared experiences of individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing. Sign language is often the primary mode of communication. The introduction of CIs, designed to enhance hearing, has sparked varied responses within the Deaf community, reflecting its diverse perspectives [37,38].

Some members view CIs as a valuable tool for individual choice and autonomy, providing access to sound and speech for better integration into the hearing world. They see these implants as a personal decision aligned with autonomy and the right to choose one’s path in life. Others approach them cautiously, expressing concerns about cultural assimilation and the potential threat to Deaf culture and sign language.

It is crucial to acknowledge the diverse and deeply personal perspectives within the Deaf community regarding CIs. While some embrace the technology for its potential benefits, others are cautious about its impact on cultural identity. This discourse mirrors broader discussions on the intersection of technology, identity, and cultural preservation. Understanding and respecting these diverse viewpoints is vital for fostering a more inclusive and informed conversation about hearing technologies within the Deaf community.

6.2. The Role of Advocacy Groups and Policy in Shaping Implantation Practices

Advocacy groups and policy are central to shaping cochlear implantation practices, exerting influence in development, adoption, and accessibility. They raise awareness about hearing impairment and CIs, disseminate information to address misconceptions, and engage with policymakers to advocate for improved access, insurance coverage, and research funding. Policy changes driven by these groups significantly impact the availability and affordability of CIs.

These entities also allocate funds for research, contributing to the refinement of implant technologies and rehabilitation strategies. Emphasizing inclusivity, they advocate for equal access across diverse demographics, working to eliminate barriers hindering certain populations. Collaborating with healthcare professionals, they establish high-quality standards for cochlear implantation, ensuring safety, efficacy, and ethical considerations. Additionally, advocacy groups empower individuals and families affected by hearing impairment, providing crucial support networks, resources, and guidance throughout the implantation process. Through awareness, policy influence, research support, and inclusivity advocacy, these entities profoundly contribute to shaping the evolution and accessibility of cochlear implantation technologies.

7. Contemporary Trends and Future Prospects

7.1. Pioneering Companies in Cochlear Implants

Professor Clark’s work in 1983 led to the formation of Cochlear Ltd. in Sydney, Australia. In 1989, Professors Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair established the MED-EL Company, headquartered in Innsbruck, Austria. These companies, along with Advanced Bionics in Zurich, Switzerland, are globally recognized leaders in CIs. As the market for CIs expanded over time, additional companies, like Nurotron Biotechnology from Hangzhou, China, joined the field, further contributing to the advancements in this area [39].

7.2. Current Criteria for Cochlear Implantation

The criteria for CIs [40] are refined through a comprehensive evaluation process. Typically, candidates exhibit severe or profound sensorineural hearing loss, irrespective of age, accompanied by a demonstrated limited benefit from conventional hearing aids. Stratified based on the onset of deafness, these criteria distinguish between prelingual and post-lingual conditions. For children, there is a lower age limit, and the current threshold for implantation has advanced to 9 months after birth, recognizing the importance of early intervention. In practice, some centers have proceeded with implantation in children much younger than 9 months. Absolute contraindications for surgery include the absence of the cochlea and auditory nerve, total cochlear ossification, and complete deafness due to pathology in areas of the central nervous system. Relative contraindications involve significant intracochlear ossification or fibrosis, congenital malformations within the inner ear, and active chronic otitis media.

Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) is a recently recognized condition characterized by sensorineural hearing loss, impacting speech comprehension due to a defect in the inner ear, auditory nerve, or their connection. This disorder primarily affects children but can also go undiagnosed in some adults. CIs are recommended for individuals with ANSD who struggle with speech comprehension despite having intact cochlear hair cells but impaired auditory nerve function [41]. The implants bypass the compromised auditory nerve, facilitating direct transmission of sound signals to the brain.

It is essential to note that while these criteria provide a general framework, there may be slight variations across countries and healthcare providers. The determination of candidacy for cochlear implantation is meticulously carried out through individualized assessments conducted by qualified audiologists and ear, nose, and throat specialists. This personalized approach ensures that the specific needs and circumstances of each individual are thoroughly considered, acknowledging the nuanced nature of hearing loss and maximizing the potential benefits of CI technology.

7.3. Expanding the Candidate Pool: Aging Populations and Adult Implantation

Expanding the candidate pool for cochlear implantation has become a significant focus in recent years, particularly with the aging of populations worldwide. As individuals age, the prevalence of hearing loss increases, leading to a growing demand for effective hearing solutions. Adult implantation has emerged as a key aspect of addressing this need, as advancements in CI technology and surgical techniques have made the procedure more accessible and beneficial for older individuals. Recognizing the impact of hearing loss on the overall well-being of aging populations, there is a concerted effort to raise awareness and provide comprehensive evaluations for potential CI candidates among adults [42]. This shift in perspective not only enhances the quality of life for older individuals by restoring auditory function but also underscores the evolving landscape of cochlear implantation to accommodate a broader demographic. Additionally, the adoption of local anesthesia with conscious sedation for implantation procedures in older individuals further contributes to making the process more feasible and comfortable, ensuring that age is not a barrier to accessing this transformative technology [43].

7.4. Biocompatible Materials and Implant Longevity

Biocompatible materials play a pivotal role in determining the longevity and success of CIs. Their longevity relies heavily on the ability of materials to withstand the complex physiological environment within the human body [44]. Over the years, there has been a significant emphasis on the use of biocompatible materials to mitigate issues such as inflammation and tissue rejection. The electrode arrays, a critical component of CIs, are often made from materials like platinum, iridium, or silicone, which are known for their biocompatibility. These materials aim to minimize the risk of adverse reactions and promote long-term stability within the cochlea. Advances in materials science have led to the development of coatings that enhance biocompatibility, reducing the likelihood of fibrous tissue formation around the implant. The use of durable and biocompatible materials not only contributes to the physical integrity of the implant but also plays a crucial role in maintaining optimal electrical performance over an extended period. As research in materials science progresses, further innovations in biocompatible materials are expected to enhance the longevity and overall reliability of CI devices.

7.5. Wireless Connectivity and Smartphone Integration

The integration of wireless connectivity and smartphone technology has marked a transformative phase in the realm of CIs, enhancing user experience and accessibility [45]. With wireless connectivity, CI users can seamlessly connect their devices to smartphones, enabling a range of functionalities that go beyond traditional hearing aid capabilities. Smartphone integration allows users to adjust settings, customize preferences, and even stream audio directly to their CIs, providing a more personalized and versatile auditory experience. Additionally, smartphone applications developed by CI manufacturers facilitate remote monitoring, troubleshooting, and software updates, empowering users to take control of their hearing journey. This integration not only simplifies the management of CI settings but also opens avenues for future innovations, fostering a more interconnected and user-centric approach in the field of auditory prosthetics.

7.6. Integration of Cochlear Implants with Other Technologies

The integration of CIs with various technologies beyond wireless connectivity is an exciting frontier in enhancing the functionality and user experience of these devices. One notable area of integration is the collaboration between CIs and artificial intelligence (AI). AI algorithms can be employed to optimize signal processing, adapt to users’ unique hearing needs, and improve speech recognition in various environments [46]. Concerning smartphone applications, integration with CIs allows users to have greater control over their device settings, access personalized hearing profiles, and even receive real-time remote adjustments from healthcare professionals. Additionally, advancements in battery technology contribute to the development of more efficient and longer-lasting power sources for CIs, ensuring sustained usage without frequent recharging. Overall, the integration of CIs with AI and advanced battery technologies showcases a promising future for improving the overall effectiveness, adaptability, and user satisfaction of CI technology.

7.7. Totally Implantable Cochlear Implants and Beyond

Totally implantable CIs are a cutting-edge solution for severe-to-profound hearing loss, distinct for being fully embedded within the ear, minimizing visibility and eliminating external components. This innovation offers a discreet and aesthetically pleasing option for those prioritizing both functionality and subtlety in hearing restoration. However, considerations include surgical risks, substantial costs, suitability limitations, variable adaptation periods, potential sound quality constraints, device malfunctions, battery replacements, and the irreversibility of the procedure [47]. Prospective users should consult professionals for a comprehensive understanding of benefits and drawbacks before deciding.

Beyond advancements in fully implantable devices, remote programming of CIs, minimizing surgical trauma, enhancing neural health through targeted drug therapy, intraneural electrode placement, and refining the interface between the neural system and the prosthesis, there is still considerable uncharted territory [48]. Exploring these avenues further is poised to yield significant progress in CI technology, fostering the development of increasingly effective and user-friendly solutions for the future.

7.8. Stem Cells and Gene Therapy in Hearing Restoration

Ongoing research explores the potential of stem cells and gene therapy to replace CIs, offering promising prospects for advancing hearing restoration. Although CIs effectively provide auditory input for sensorineural hearing loss, stem cells and gene therapy present innovative approaches to address the root causes at a cellular and molecular level [49]. Stem cell therapy aims to regenerate damaged or lost hair cells in the inner ear, while gene therapy focuses on correcting genetic factors associated with hearing impairment. Despite being in early research stages, these approaches hold exciting potential for the future of hearing restoration. However, practical application and widespread adoption necessitate further development, testing, and addressing potential challenges.

8. Conclusions

The story of CIs unfolds with a fascinating blend of breakthroughs and technological progress. The journey of CI technology has not only reshaped auditory rehabilitation but has also become a central element in the ongoing narrative of innovation. As CIs continue to redefine the possibilities in hearing restoration, the intricate dance between technological advancements and the evolving landscape of auditory solutions takes center stage. This historical narrative prompts a continuous exploration and discussion to ensure that CIs remain aligned with the ever-evolving technological landscape, contributing to increasingly refined outcomes in auditory rehabilitation. The historical progression of CIs highlights their dynamic role and transformative impact on the journey of hearing restoration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, I.A.; Methodology, Investigation, M.A. and P.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.A. and P.S.; Review and Editing, I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mudry, A.; Mills, M. The Early History of the Cochlear Implant: A Retrospective. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macherey, O.; Carlyon, R.P. Cochlear Implants. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R878–R884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. A Treatise on Electricity, 2nd ed.; Davis: London, UK, 1752; pp. 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Volta, A. On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds. Philos. Trans. 1800, 90, 403–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchenne, G.B.A. De L’électrisation Localisée et de son Application à la Physiologie, à la Pathologie et à la Thérapeutique; Baillière: Paris, France, 1855; Volume 73, pp. 807–813. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, L.F. Electric Ostephone. U.S. Patent 792162, 13 June 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Wever, E.G.; Bray, C. The Nature of Acoustic Response: The Relation Between Sound Frequency and Frequency of Impulse in the Auditory Nerve. J. Exp. Psychol. 1930, 11, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersuni, G.V.; Volokhov, A.A. On the Electrical Excitability of the Auditory Organ: The Effect of Alternating Currents on the Normal Auditory Apparatus. J. Exp. Psychol. 1936, 19, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, H. Remaking Speech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1939, 11, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.C.; Stevens, S.S.; Lurie, M.H. Three Mechanisms of Hearing by Electrical Stimulation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1940, 12, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, N.L.; Dowling, E.M.; Jethanamest, D.; Carlson, M.L. Cochlear Implantation: An Overview. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2019, 80, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djourno, A.; Eyries, C. Auditory Prosthesis by Means of a Distant Electrical Stimulation of the Sensory Nerve with the Use of an Indwelt Coiling. Presse Med. 1957, 65, 1417. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.; Doyle, D.; House, W. Electrical Stimulation of Eight Nerve Deafness. Bull. Los Angeles Neurol. Soc. 1963, 28, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, F.B. Electrical Stimulation of the Auditory Nerve in Man. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1966, 84, 2–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzenich, M.M.; Michelson, R.P.; Pettit, C.R.; Schindler, R.A.; Reid, M. Neural Encoding of Sound Sensation Evoked by Electrical Stimulation of the Acoustic Nerve. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1973, 82, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshraghi, A.A.; Nazarian, R.; Telischi, F.F.; Rajguru, S.M.; Truy, E.; Gupta, C. The Cochlear Implant: Historical Aspects and Future Prospects. Anat Rec. 2012, 295, 1967–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilger, R.C.; Black, F.O. Auditory Prostheses in Perspective. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1977, 86, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, G.M.; Tong, Y.C.; Black, R.; Forster, I.C.; Patrick, J.F.; Dewhurst, D.J. A Multiple-Electrode Cochlear Implant. J. Otolaryngol. Soc. Austral. 1978, 4, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauterkus, G.; Maxwell, A.K.; Kahane, J.B.; Lentz, J.J.; Arriaga, M.A. Conversations in Cochlear Implantation: The Inner Ear Therapy of Today. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadarajan, V.V.; Sydlowski, S.A.; Li, M.M.; Anne, S.; Adunka, O.F. Evolving Criteria for Adult and Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangabeira Albernaz, P.L. History of Cochlear Implants. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.S.; Dorman, M.F. Cochlear Implants: A Remarkable Past and a Brilliant Future. Hear. Res. 2008, 242, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Shallop, J.; Peterson, A. Speech Recognition Materials and Ceiling Effects: Considerations for Cochlear Implant Programs. Audiol. Neurotol. 2008, 13, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamati, T.; Pisoni, D.B.; Moberly, A.C. Speech and Language Outcomes in Adults and Children with Cochlear Implants. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2022, 8, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasingh, A.; Hochmair, I. Bilateral Cochlear Implantation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2021, 141, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, J.J.; Stern Shavit, S.; Vicario-Quinoñes, F.; Lalwani, A.K. Is Bilateral Cochlear Implantation Cost-Effective Compared to Unilateral Cochlear Implantation? Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forli, F.; Bruschini, L.; Franciosi, B.; Berrettini, S.; Lazzerini, F. Sequential bilateral cochlear implant: Long-term speech perception results in children first implanted at an early age. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasingh, A.; Hochmair, I. Signal processing & audio processors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2021, 141, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pisoni, D.B.; Kronenberger, W.G.; Harris, M.S.; Moberly, A.C. Three Challenges for Future Research on Cochlear Implants. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 3, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.A.; Lee, J.A.; Nguyen, S.A.; McRackan, T.R.; Meyer, T.A.; Lambert, P.R. Cochlear Implantation for Treatment of Tinnitus in Single-sided Deafness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e1004–e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, N.R.; Holder, J.T.; Patro, A.; Cass, N.D.; Tawfik, K.O.; O’Malley, M.R.; Bennett, M.L.; Haynes, D.S.; Gifford, R.H.; Perkins, E.L. Cochlear Implants for Single-Sided Deafness: Quality of Life, Daily Usage, and Duration of Deafness. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 2362–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.P.M.; van Heteren, J.A.A.; Wendrich, A.W.; van Zanten, G.A.; Grolman, W.; Stokroos, R.J.; Smit, A.L. Short-term outcomes of cochlear implantation for single-sided deafness compared to bone conduction devices and contralateral routing of sound hearing aids-Results of a Randomised controlled trial (CINGLE-trial). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, B.; Hogg, E.S.; Patefield, A.; Strachan, L.; Sharma, S.D. Hearing outcomes in children with single sided deafness: Our experience at a tertiary paediatric otorhinolaryngology unit. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 167, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, A.; Delcenserie, A.; Champoux, F. Auditory Event-Related Potentials Associated With Music Perception in Cochlear Implant Users. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 7, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spangmose, S.; Hjortkjær, J.; Marozeau, J. Perception of Musical Tension in Cochlear Implant Listeners. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, M.K.; Quimby, A.E.; Bartellas, M.; Kaufman, H.S.; Bigelow, D.C.; Brant, J.A.; Ruckenstein, M.J. Long-Term Hearing Outcomes After Hybrid Cochlear Implantation. Otol. Neurotol. 2023, 44, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A. Hear Me Out: Hearing Each Other for the First Time-The Implications of Cochlear Implant Activation. Mo. Med. 2019, 116, 469–471. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, B.; Alexander, S.P.; McMenamin, K.; Welch, D. Deaf community views on paediatric cochlear implantation. N. Z. Med. J. 2022, 135, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Ni, W.; Li, W.; Li, H. Cochlear Implantation and Rehabilitation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1130, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biever, A.; Kelsall, D.C.; Lupo, J.E.; Haase, G.M. Evolution of the Candidacy Requirements and Patient Perioperative Assessment Protocols for Cochlear Implantation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2022, 152, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, R.J.; Nassiri, A.M.; Rivas, A. Auditory Neuropathy: Bridging the Gap Between Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 52, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, S.S.; Goldstein, M.R.; Morris, S.A.; Jacob, A. Cochlear Implant Outcomes in the Very Elderly. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabashev, S.; Fouad, Y.; Huncke, T.K.; Roland, J.T. Cochlear Implantation Under Conscious Sedation with Local Anesthesia: Safety, Efficacy, Costs, and Satisfaction. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2017, 18, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spałek, J.; Ociepa, P.; Deptuła, P.; Piktel, E.; Daniluk, T.; Król, G.; Góźdź, S.; Bucki, R.; Okła, S. Biocompatible Materials in Otorhinolaryngology and Their Antibacterial Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.H.; Jung, Y.; Hur, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.Y. Feasibility of Speech Testing Using Wireless Connection in Single-Sided Cochlear Implant Users. J. Audiol. Otol. 2023, 27, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltzman, S.B.; Kelsall, D.C. The Use of Artificial Intelligence to Program Cochlear Implants. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trudel, M.; Morris, D.P. The Remaining Obstacles for a Totally Implantable Cochlear Implant. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forli, F.; Lazzerini, F.; Bruschini, L.; Danti, S.; Berrettini, S. Recent and future developments in cochlear implant technology: Review of the literature. Otorhinolaryngology 2021, 71, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Park, Y.H. Potential of Gene and Cell Therapy for Inner Ear Hair Cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8137614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).