Abstract

Vulnerable populations experience higher mortality and readmission after hospital discharge. We sought to evaluate the impact of the Transitions Of Care Bundle (TOCB™) on COVID-19 patient outcomes post-discharge compared to a control cohort. This retrospective study used electronic health record data collected for 243 COVID-19 patients (65 TOCB™, 178 control) during the initial pandemic months at a large academic facility in Northeast New Jersey (NJ). Data included demographics, comorbidities, readmissions, mortality, and payor. The TOCB™ cohort had proportionally more Hispanic patients (56.92% vs. 48.3%, p = 0.0885). All TOCB™ patients were discharged home without needing additional services, compared to only 36% of the control group. The implementation of TOCB™ was associated with shorter hospital stays, a potential decrease in readmission rates, and fewer emergency department visits. These results imply that well-coordinated post-discharge services are linked to a diminished risk of mortality, possible hospital readmission, and other adverse health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Persistently high mortality rates, preventable readmission, and adverse outcomes in vulnerable populations call for a comprehensive, collaborative transition of care model [1,2,3]. Transition of care (TOC) models refer to interventions that keep all patients safe as they move between healthcare settings and care levels, including care coordination, advanced care planning, patient education, self-care, and medication management [4,5,6]. Indigent populations across the United States (US) often present to healthcare facilities underinsured and unable to navigate the system to apply for benefits [7,8,9]. Lack of access to care increases risk of hospital readmissions and poor health outcomes [10,11,12]. Low educational attainment, limited health literacy, and social determinants of health (SDoH) disparities contribute to poor outcomes, emphasizing an urgent need to implement interventions to prevent patients from becoming hospitalized [13,14,15].

Disparities in SDoH contribute to poor health outcomes [16,17,18], but it is often difficult to find opportunities to test targeted interventions for vulnerable populations. However, during the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the healthcare system received a large volume of patients from underserved communities with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and provided such an opportunity. Specifically, caring for patients during the pandemic provided an opportunity to test an innovative program bundle in crisis to assess its effect on this population. The Transitions of Care Bundle (TOCB) comprises nurse care coordination, medication reconciliation, post-discharge phone calls, provision of shared-ride transportation, and an individualized Wellness Package with self-monitoring tools. These components are initiated during admission and continue post-discharge. Important considerations include emergency department (ED) return visits, hospital readmission, mortality, and length of stay (LOS) [19,20]. Though prior work exists to address this gap, it is yet to be determined if a TOCB can impact mortality rate, readmissions, and patient health outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to establish and test a bundle of interventions, such as the TOCB described above, during a crisis. This paper aims to examine the utilization and possible impact of the TOCB of interventions by a dedicated TOC team during a period of healthcare crisis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

Hackensack University Medical Center (HUMC), a large academic facility in Northeast New Jersey (NJ) with 803 beds, was the study site, with the study performed in during 2020. As part of the state’s largest healthcare network, HUMC has more than 100,787 ED visits annually, with 23% of patients being admitted.

2.2. Study Design and Study Sample

This observational study includes patients who received the TOCB and patients who received a standard discharge (the No-TOCB cohort). The project included patients referred by admitting physicians. All patients had a diagnosis of COVID-19 or were persons under investigation (PUI), age 18 and older. The study sample included 65 adult patients who received the TOCB and 178 control patients who did not. All patients were discharged within the first three months of the pandemic. Prior approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.3. The Intervention

The TOCB care team was made up of two Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) and a Registered Nurse (RN), whose responsibilities included care coordination, monitoring patients post-discharge, and addressing SDoH. During the patient’s index admission, the TOCB care team actively advocated for the specific individual’s needs. Through systematic collaboration with the broader clinical care team, the TOCB team was instrumental in instituting necessary interventions. This continuum of care was sustained post-discharge, with the TOCB care team conducting diligent follow-up to ensure safe transition from hospital to home. The TOCB comprises five interventions that embrace a patient-centered care philosophy, including care coordination, medication reconciliation, discharge phone calls, transportation, and an individualized Wellness Package. The Wellness Package includes self-monitoring tools like blood pressure machines, glucometers, pulse oximeters, and Durable Medical Equipment (DME) such as home oxygen. These tools were given to patients during the admission, along with instructions on using them and documenting findings. The findings were reported to the team during the post-discharge period and also shared with the outpatient provider. The above interventions focus on creating linkage to community-based organizations (CBOs), addressing SDoH and other health-related social needs (HRSNs).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Propensity Score Matching

In order to evaluate the differences in clinical outcomes between the intervention and control cohorts, a comparative analysis of a matched cohort design was pursued. Since cases (TOCB recipients) and controls (No-TOCB) were observed in the same window of the first three months of the pandemic, propensity score matching (PSM) was chosen as a suitable approach for ensuring the patients in the cohorts are comparable. PSM uses a vector of covariates from the COVID-19 patients to predict the probability of receiving TOCB and not receiving TOCB. In particular, the propensity score is the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed baseline characteristics. The goal of the PSM was to ensure the distribution of observed baseline covariates was similar between TOCB and No-TOCB subjects. To achieve the distributional balance in the covariates while comparing to the unmatched samples, we explored several PSM methods, including a full match and nearest neighbor with a caliper of 0.22 and a caliper of 0.25. Caliper is defined as the tolerance for the difference in the propensity scores between the TOCB and No-TOCB groups. The matching was performed utilizing the variables: gender (male vs. female), age class [younger (age: 30–45 years) vs. midlife (age: 45–64 years) vs. older (64–94 years)], race/ethnicity [white (non-Hispanic) vs. Hispanic vs. Black (non-Hispanic) vs. Asian/Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) vs. other vs. unknown], insurance status (Medicare vs. self-pay vs. charity vs. Medicaid vs. private), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, yes vs. no), hypertension (yes vs. no), body-mass index (BMI)-class revised (underweight and normal weight vs. overweight vs. obese), diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) and stroke (yes vs. no). In this study, the quality and adequacy of the quality of balance of covariates were assessed using standardized mean differences, ratio of variances, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov, as well as the use of love plots and balance plots.

2.4.2. Variables and Measures

Variables collected included additional diagnoses, payor sources, and services provided. Post-hospitalization outcomes included LOS, return ED visits, and 30-day hospital readmissions. Demographic information collected from the electronic health record (EHR) included race, ethnicity, age, gender, zip code, and county. To reduce errors in chart abstraction, trained chart abstractors utilized a double data entry methodology to collect and enter data into a REDCap database.

2.4.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and present the demographic and clinical data. Comparisons of continuous variables between independent groups, such as in the unmatched samples of TOCB and No-TOCB were performed using two-sided two-sample t-tests or two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. Comparisons of continuous variables between dependent groups, such as in the matched samples of TOCB and No-TOCB were performed using two-sided paired t-tests or two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, as appropriate. Comparison of categorical variables between independent groups, such as the unmatched samples of TOCB and No-TOCB were conducted using two-sided Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s chi-square test, as appropriate. Comparison of categorical variables between dependent groups, such as the matched samples of TOCB and No-TOCB were conducted using two-sided McNemar’s test or Bowker’s test of symmetry, as appropriate.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), except for propensity matching, which was performed using the package MatchIt version 4.5.1; covariate balance was performed using the package Cobalt version 4.5.0 in R 4.2.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Any p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Any 0.05 ≤ p < 0.10 was considered trending toward significance.

We compared clinical outcomes in patients who received the intervention to those who did not within the first three months of the coronavirus pandemic. Specifically, the LOS coupled with discharge disposition was examined so that the primary outcome, “time to being discharged to home without services,” as a time-to-event endpoint, was compared between the two cohorts. For this endpoint, death during the hospitalization was considered a competing risk to being discharged to home without services; patients discharged to other less acute-care centers for rehabilitation were censored at the time of discharge. The cumulative incidence functions (CIF) for patients who received TOCB and patients who did not receive TOCB were estimated, and incidence rates at 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days since admission were estimated from the CIF curves. A comparison of CIFs between the cohorts was performed using Gray’s test of equality of CIFs. The benefit of being discharged to home without services was assessed by fitting the Fine-Gray model and reporting the hazard ratio (HR), taken as the benefit ratio, and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

3. Results

A total of 65 patients (27% of the study sample) received care as part of the TOCB intervention (Cohort A), and 178 patients (73% of the study sample) did not receive the TOCB intervention (Cohort B). Patient selection was done by matching the 65 patients to a sample of 178 patients who did not receive the TOCB interventions but had similar demographic diagnoses and received care during the same time period and location.

In this study, 243 charts met the criteria for study entry of a median age of 61.0 years (IQR 51.0–59.0 years), with actual age ranging from 30.0 to 94.0 years. Of the 243 patients, 147 (60.5%) were male. 233 (95.9%) were from NJ, with most patients from Bergen (56.8%), Passaic (21.8%), and Hudson (10.7%) counties. 65 of the 243 patients were in the TOCB cohort, and 178 of them did not receive the TOCB. A comparison of the characteristics of the matched patients in the No-TOCB and TOCB cohorts is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Matched Characteristics of No-TOCB and TOCB COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients.

Nearest Neighbor (Nn) Propensity Score Matched Sample

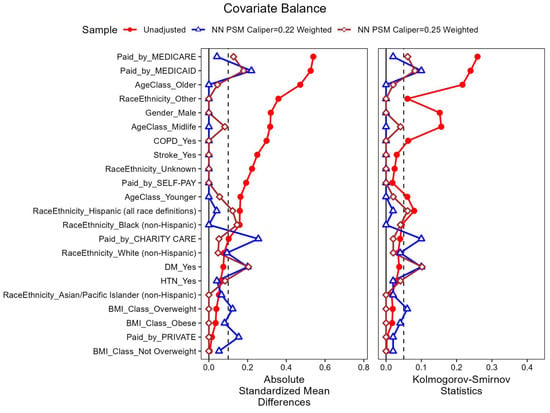

The results of a propensity score matching sample step on nearest-neighbor and caliper = 0.22 conducted with an exact match requirement for gender and age class yielded a 1:1 matched sample of 50 TOCB-No-TOCB pairs. The comparative analysis of characteristics in Table 2 shows that there were no significant differences between the two TOCB cohorts after the NN-PSM. The analysis of covariate balance between the matched cohorts (Figure 1 and Figure 2) indicated that the NN-PSM had achieved good distributional balance.

Table 2.

Summary of Outcomes of No-TOCB and TOCB in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients.

Figure 1.

Overlaid Love Plots for Unweighted sample [No-TOCB (n = 167) vs. TOCB (n = 63)]; Nearest-neighbor (NN) PSM Caliper = 0.22 Weighted Sample [No-TOCB (n = 50) vs. TOCB (n = 50)]; Nearest-neighbor (NN) PSM Caliper = 0.25 Weighted Sample [No-TOCB (n = 49) vs. TOCB (n = 49)]. The vertical dotted line at 0.1 in the love plot for absolute standardized mean differences ndicates the maximum cutoff value for good covariate balance. The vertical dotted line at 0.05 in the love plot Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic indicates the maximum cutoff value for differences in the empirical cumulative distribution function between two cohorts.

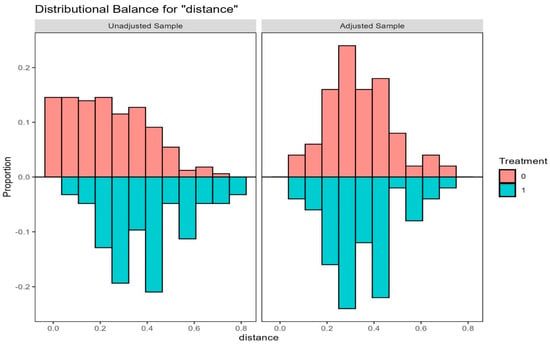

Figure 2.

Mirrored Histogram of Distance in Unweighted and Nearest-neighbor 1:1 Propensity Score Matched (PSM) sample with Caliper = 0.22, where Age Class and sex are exactly matched for COVID-19 patients with No-TOCB (n = 50) and with TOCB (n = 50). Treatment = 0, depicted in salmon pink color, represents the cohort that did not receive TOCB (No-TOCB). Treatment = 1, depicted in green color, represents the cohort that received TOCB (TOCB).

After applying a nearest-neighbor propensity match method, we analyzed a sample of 100 patients, with 50 patients (F/M: 15/35) in the No-TOCB cohort aged 56.5 yrs (IQR, 48.0–65.0 yrs) and 50 patients (F/M: 15/35) in the TOCB cohort aged 57.0 yrs (IQR, 49.0–67.0 yrs). A comparison of all characteristics of the PS-matched patients in the No-TOCB and TOCB cohorts is presented in Table 1.

Patient outcomes of the two PS-matched cohorts are presented in Table 2. Discharge disposition distribution was different between the No-TOCB and TOCB cohorts since all 50 TOCB patients were discharged to home without additional services after receiving the TOCB, while only 33 (64.0%) of the No-TOCB were discharged to home without needing additional services. Further, mortality occurrence in the No-TOCB cohort was higher than in the TOCB cohort [15 (30.0%) vs. 0 (0.0%)]. Of the 30 mortalities in the No-TOCB, 1 occurred after discharge, while 14 (93.3%) occurred during the index hospital stay. Consequently, all mortality-related outcomes-during admission, 30-day, 60-day, 90-day, and beyond 90-day post-discharge reported significant differences between the cohorts.

An analysis of length of stay in the PS-matched cohort, not accounting for discharge disposition, reported a longer LOS in the No-TOCB (median = 8.5 days, IQR: 2.0 to 12.0 days) than in the TOCB (median = 6.5 days, IQR, 4.0 to 10 days); however, the paired difference (median = −1.0 days, IQR, −7.0 to 5.8 days) was not statistically significant.

The primary outcome of incidence of discharge to home without services, taking in-hospital death as a competing risk, indicated that the rate of being discharged was much higher in the TOCB cohort than in the No-TOCB cohort in patients who were discharged alive. COVID-19 patients in the TOCB cohort had an 86% increased benefit of being discharged to home without services compared to COVID-19 patients in the No-TOCB cohort (hazard ratio = 1.86; 95% CI 1.22 to 2.82, Supplemental Figure S1).

4. Discussion

Patients with care coordination had a shorter LOS, likely since all post-discharge services were arranged promptly. After the TOCB implementation, the discharge process became efficient because of established workflows with specific community partners. The HMH inpatient physicians developed trust in the process and were comfortable referring patients for discharge. As a result, the LOS decreased for the 65 patients in the TOCB cohort, who were successfully discharged without requiring any extra services beyond those already coordinated. As depicted in Table 2, mortality impacted only those patients in Cohort B (25.28%), which might be attributed to the lack of exposure to TOCB. Additionally, comorbidities like hypertension (HTN) and diabetes mellitus (DM) were prevalent in both groups, which could have contributed to poor health outcomes.

According to the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), women are 30% more likely than men to attend medical appointments and 100% more likely to seek preventive care [21,22]. Study findings revealed more males in both cohorts, which can be attributed to a preponderance of admissions for males with COVID-19 [23,24]. During this time, only patients who were severely ill and in need of oxygen were admitted to the hospital. Minority populations, such as Hispanics, are less likely to have medical insurance and receive primary care [25,26]. This population often seeks care when symptoms are severe and life-threatening [27,28,29]. A financial barrier often results in this population seeking delayed treatment, as reported that 36% of Hispanic adults have trouble paying medical bills in 2023 [30]. Other studies found that individuals with COVID-19 and additional comorbidities who experience delays in medical care have a higher risk of mortality [31,32,33]. According to the CDC, Hispanics have higher risk factors and are more likely to be hospitalized with a positive COVID-19 diagnosis [33,34,35]. In alignment with other studies, this study revealed a higher percentage of Hispanic patients who became critically ill as a result of COVID-19, with 56.9% in Cohort A and 48.3% in Cohort B as indicated in Table 2 [36,37]. The next highest group in illness severity of COVID-19 was White, which seemed unexpected with 24.6% in Cohort A and 20.79% in Cohort B as depicted in Table 1. Of all the COVID-19 patients who died during their hospital stay, the majority were of Hispanic ethnicity (47.37%), followed by White non-Hispanic (21.05%). Although readmission rates were generally low, the impact on readmissions has yet to be determined and requires a larger study [38].

In response to the unprecedented surge in patients and significant staffing limitations during this period, a specialized TOC team was established immediately and proactively. This “all hands on deck” initiative was a critical measure to manage the overwhelming patient influx and ensure continuity of care.

The personnel composition of this team was intentionally and strategically composed of experienced Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) and a Registered Nurse serving as care navigators. This decision was based on the unique and extensive qualifications of nurses, who possess expert knowledge, complex decision-making skills, and advanced clinical competencies. The established expertise in leadership, patient care coordination, and clinical protocol development was paramount in a crisis where rapid, effective, and safe patient transitions were essential.

Crucially, the formation of this specialized team did not incur any additional costs, as it was assembled by strategically reallocating existing team members’ roles. This fiscally responsible approach enabled a rapid, agile response to the crisis by leveraging in-house talent and resources, ensuring the organization could enhance patient care delivery during a period of immense strain without the financial burden of new hires. The formation of this team underscored a necessary strategic response to the pandemic, leveraging the highest level of expertise to navigate the complexities of patient care transitions amidst severe resource constraints.

The implementation of the TOCB provides a valid case for supporting a patient cohort during such a crisis. The effectiveness of this program relies on care navigators serving as the primary point of contact for post-discharge planning, scheduling follow-up appointments, providing patient-specific education, and addressing patient concerns before they escalate.

The implementation of the TOCB intervention resulted in a notable reduction in hospital stay, leading to potential cost savings. Patients in the TOCB cohort had a median hospital stay that was 2 days shorter than the No-TOCB group (6.5 days vs. 8.5 days). This 100-day reduction across the entire 50-patient cohort translates into a substantial financial benefit. Using the national average hospital-day cost of approximately $3025 [39], the estimated savings amount to $302,500. In essence, the TOCB intervention demonstrates a clear clinical benefit by shortening patient hospital stay, which in turn creates a strong opportunity for a positive financial return. This not only helps avoid costly penalties from payors such as Medicare but also reduces unreimbursed costs associated with high-acuity care. The program’s significant value lies in its ability to improve patient outcomes and reduce mortality rates, thereby fulfilling the organization’s core mission while enhancing its financial health.

Limitations include all those typical of a retrospective observational data analysis study: investigators were limited to the information available in the chart, including a possibility of selection bias or misclassification. Another limitation was that cohort A, which received the TOCB, was a sample of convenience and not randomized because the TOCB of interventions were offered to all patients in need and the sample size was small which may affect the statistical power and precision of our estimates. Another limitation is that LOS, mortality, and readmission measures were calculated based on Medicaid, low insurance, or no insurance (TOCB program-qualifying patients). Hence, whether the findings are similar among commercially insured populations remains uncertain. Also, data was collected early during the COVID-19 pandemic, which had multiple challenges, including connecting immigrants living on the fringes of society to healthcare for the first time. Though the examined sample included uninsured individuals, many without proper immigration documentation to reside in the US, disqualifying them from governmental assistance like Medicaid or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) may have introduced confounders.

This study’s strengths include the fact that the rates measured were not obtained from administrative claims data and, consequently, had complementary detailed clinical information. Also, this study enabled the construction and quantitative evaluation of the TOCB tool. This work adds to the limited evidence on TOC interventions and specific healthcare outcomes. The appraisal of this paper was conducted using the STROBE guidelines [40].

This study looked at “time to discharge to home without services,” ED visits, risk of mortality, and readmissions at 30 days and post-90 days for patients who received a TOCB vs. those who did not, among a cohort of COVID-19 or PUI, in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Examining data results from the TOCB and No-TOCB cohorts yielded different outcomes, with the TOCB cohort associated with better outcomes. The findings call for urgent action to enhance patient care with TOCB to meet the needs of underserved communities. Addressing SDoH with interventions like care coordination, transportation, or a post-discharge call can make a difference. TOC involves the deliberate organization and coordination of patient care services, which increases patient safety and satisfaction [41,42]. Historically, patient care was limited to the inpatient setting; however, this project emphasizes the importance of extending care plans beyond hospital walls [43,44,45]. Policies and procedures must clearly define the process and interventions for clinical teams to enhance the discharge process for disadvantaged communities. Additionally, new or existing resources must be allocated efficiently and equitably to improve the quality of care and patient safety in marginalized groups [46,47,48].

Disparities in income, education, employment, and social support have been used to create an SES index. People with a lower SES face decreased life expectancy, stemming from the inequities, leading to detrimental health outcomes [11,49,50].

Our TOCB intervention targets key social elements of the SDoH–the non-medical conditions where people are born, grow, work, and live that fundamentally shape outcomes [51]; we are confident that our TOCB is addressing the needs identified as integral to an SES-based model for SDoH gaps. Future studies might be beneficial in developing a score that could be examined for similar correlation.

5. Conclusions

As the global landscape of COVID-19 evolved, the TOCB was applied to a cohort of patients, and the new findings revealed the potential for increasing the likelihood of hospitalized patients being discharged to home without needing services, decreasing mortality, LOS and, possibly, hospital readmissions. Individuals of Hispanic and African American descent, with underlying chronic conditions and health-related social needs, faced a higher susceptibility to contracting the virus and experiencing severe illness. The clinical findings of this study bring new knowledge about the critical importance of efficient and early coordination of post-discharge services, as failure to do so could place patients at increased risk of hospital readmission and mortality. Findings from this project yielded promising results with decreasing LOS, mortality, ED return visits, and potentially reduce readmission. Individuals with chronic diseases must be provided with TOCB-like interventions that can secure their way back to recovery and healthy living. This study also enabled the assembly, construction, and quantitative evaluation of the TOCB. Future research should seek reliability and validation of the TOCB as well as examine the application of the TOCB in other groups of underserved patients, such as those with chronic conditions or non-communicable diseases.

The 30-day period following hospital discharge is a critical, highly vulnerable phase in a patient’s recovery journey. The moment a patient leaves the hospital, there’s always a risk period. Research has consistently shown that adverse events are alarmingly common, which are frequently preventable and often stem from systemic breakdowns in communication and post-discharge preparation. During the crucial transition period, a structured post-hospital support program that leverages seamless care coordination, transforming the traditional procedural checklist into a proactive, patient-centered approach, bridges the gap between hospital and home. Whether the post-discharge challenge becomes a full-blown crisis often depends on the availability of resources [52] A lack of support on either the patient or system side can quickly escalate a manageable issue into a more extended hospital stay and costly readmission. To mitigate risks, our healthcare organization shifted from a reactive to a proactive discharge model. The involvement of patients in this process has been essential in enhancing collaboration, increasing adherence to treatment plans, and boosting confidence in managing conditions at home.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid6010013/s1, Figure S1: Incidence Functions of Discharge to Home.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.; formal analysis, T.N.; data curation, T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.; writing—review and editing, V.C., J.C., T.N. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was formally reviewed and approved by the Hackensack Meridian Health Institutional Review Board (Protocol #PRO2020-0592, approved 10 February 2021) in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This research and quality improvement projects, which were classified as a minimal risk study involving human subjects, underwent an expedited review process. Given the nature of the study, the IRB granted waivers for both informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study. The research involved pre-existing patient data from electronic medical records and posed no harm other than a minimal risk of breach of confidentiality. It was not feasible to contact patients to obtain consent, and all data were de-identified and analyzed in aggregate.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions, as the dataset contains protected health information derived from patient electronic health records. To maintain patient confidentiality in accordance with ethical guidelines, all data were coded and stored in a secure, encrypted, password-protected database with access limited to authorized study personnel. The aggregated data that support the findings of this study are presented within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Carmen Luna; Nida Ali; Dyna Pierre, and Craig Solid.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APN | Advanced Practice Nurse |

| BMI | Body-mass index |

| CBO | Community-based organization |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CIF | Cumulative incidence function |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DME | Durable medical equipment |

| ED | Emergency department |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HRSN | health-related social need |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| HMH | Hackensack Medical Center |

| HUMC | Hackensack University Medical Center |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| NN | Nearest Neighbor |

| PUI | Persons under investigation |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| RN | Registered nurse |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| SDoH | Social determinants of health |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| TOCB | Transition of care bundle |

References

- Ojo, S.; Okoye, T.O.; Olaniyi, S.A.; Ofochukwu, V.C.; Obi, M.O.; Nwokolo, A.S.; Okeke-Moffatt, C.; Iyun, O.B.; Idemudia, E.A.; Obodo, O.R.; et al. Ensuring Continuity of Care: Effective Strategies for the Post-hospitalization Transition of Psychiatric Patients in a Family Medicine Outpatient Clinic. Cureus 2024, 16, e52263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.E.; Haselden, M.; Corbeil, T.; Tang, F.; Radigan, M.; Essock, S.M.; Wall, M.M.; Dixon, L.B.; Wang, R.; Frimpong, E.; et al. Relationship Between Continuity of Care and Discharge Planning After Hospital Psychiatric Admission. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwobah, E.; Jaguga, F.; Robert, K.; Ndolo, E.; Kariuki, J. Efforts and Challenges to Ensure Continuity of Mental Healthcare Service Delivery in a Low Resource Settings During COVID-19 Pandemic-A Case of a Kenyan Referral Hospital. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 588216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrais, D.J.L.; Gomes, M.C.; da Cunha, C.L.F.; Riegel, F.; da Costa, M.F.B.N.A.; Aben-Athar, C.Y.U.P.; Ramos, A.M.C.; Parente, A.T.; Rodrigues, D.P.; de Sousa, F.J.D. Transition of Care for Post-COVID-19 Patients: Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile and Associated Factors. Nurs. Forum 2023, 2023, 3505657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansukhani, R.P.; Bridgeman, M.B.; Candelario, D.; Eckert, L.J. Exploring Transitional Care: Evidence-Based Strategies for Improving Provider Communication and Reducing Readmissions. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 690–694. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, C.; Johnston-Fleece, M.; Johnson, M.C., Jr.; Shifreen, A.; Clauser, S.B. Patient-Centered Approaches to Transitional Care Research and Implementation: Overview and Insights From Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s Transitional Care Portfolio. Med. Care 2021, 59, S330–S335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Kelley, A.T.; Morgan, A.U.; Duong, A.; Mahajan, A.; Gipson, J.D. Challenges for Adult Undocumented Immigrants in Accessing Primary Care: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Workers in Los Angeles County. Health Equity 2020, 4, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Kluender, R.; Mahoney, N.; Wang, J.; Wong, F.; Yin, W. The Impact of Financial Assistance Programs on Health Care Utilization: Evidence from Kaiser Permanente. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2022, 4, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiyachati, K.H.; Qi, M.; Werner, R.M. Nonprofit Hospital Community Benefit Spending and Readmission Rates. Popul. Health Manag. 2020, 23, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, S.; John, D.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y.; Mattingly-App, A.; Jain, S.; Chang, E.Y.; Ongkeko, W.M. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic-Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singu, S.; Acharya, A.; Challagundla, K.; Byrareddy, S.N. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Emerging COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcendor, D.J. Racial Disparities-Associated COVID-19 Mortality Among Minority Populations in the US. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ju, X.; Zhang, X. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melix, B.L.; Uejio, C.K.; Kintziger, K.W.; Reid, K.; Duclos, C.; Jordan, M.M.; Holmes, T.; Joiner, J. Florida neighborhood analysis of social determinants and their relationship to life expectancy. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.; Shoker, M.; Chu, L.M.; Frehlick, R.; Ward, H.; Pahwa, P. Impact of low health literacy on patients’ health outcomes: A multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H.; Fernandez, R.; MacPhail, C. The social determinants of health and health outcomes among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Public Health Nurs. 2021, 38, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Natale, G.; Link, B.G. Socioeconomic inequalities in the spread of coronavirus-19 in the United States: A examination of the emergence of social inequalities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Asaria, M.; Stranges, S. COVID-19 and inequality: Are we all in this together? Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, M.E.; Gottlieb, L.M.; Doubeni, C.A.; Viswanathan, M.; Cartier, Y.; Aceves, B.; Fichtenberg, C.; Cené, C.W. Advancing health equity through social care interventions. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, A.; Negussie, Y.; Geller, A.; Weinstein, J.N. (Eds.) Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.E.; Anisimowicz, Y.; Miedema, B.; Hogg, W.; Wodchis, W.P.; Aubrey-Bassler, K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hunt, K.; Nazareth, I.; Freemantle, N.; Petersen, I. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballering, A.V.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Olde Hartman, T.C.; Rosmalen, J.G.M.; Lifelines Corona Research Initiative. Sex and Gender-Related Differences in COVID-19 Diagnoses and SARS-CoV-2 Testing Practices During the First Wave of the Pandemic: The Dutch Lifelines COVID-19 Cohort Study. J. Womens Health 2021, 30, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, A.; Fathabadi, A.; Razmi, M.; Zarifian, A.; Amiri, M.; Ghodsi, A.; Moradi, E.V. Characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes associated with readmission in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 52, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, K.; Conmy, A.; Chu, R.C.; Bosworth, A.; Sommers, B.D. Trends in the US Uninsured Population, 2010–2020; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unemployment Rate Falls to 6.9 Percent in October 2020. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-falls-to-6-point-9-percent-in-october-2020.htm (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Buchmueller, T.C.; Levy, H.G. The ACA’s Impact On Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Health Insurance Coverage And Access To Care. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder-Dixon, A.R.; Adams, O.R.; Cobb, T.L.; Goldberg, A.J.; Fikslin, R.A.; Reinka, M.A.; Gesselman, A.N.; Price, D.M. Medical avoidance among marginalized groups: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 45, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage: Dynamics of Gaining and Losing Coverage over the Life-Course. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2017, 36, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. How Does Cost Affect Access to Healthcare? Available online: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/cost-affect-access-healthcare/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Patidar, R.; Younis, K.; Desai, P.; Hosein, Z.; Padda, I.; Mangat, J.; Altaf, M. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Hu, K.; Chen, G.; Wei, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhou, C.; Yu, H.; et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Jacobson, M.; Chang, T.Y.; Shah, M.; Pramanik, R.; Shah, S.B. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Testing and COVID-19 Outcomes in a Medicaid Managed Care Cohort. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Snyder, V.N.S.; McDaniel, M.; Padilla, A.M.; Parra-Medina, D. Impact of COVID-19 on Latinos: A Social Determinants of Health Model and Scoping Review of the Literature. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2021, 43, 174–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Medical Association. Social Determinants of Health: Health Systems Science Learning Series; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Andermann, A.; CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. CMAJ 2016, 188, E474–E483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogedegbe, G.; Ravenell, J.; Adhikari, S.; Butler, M.; Cook, T.; Francois, F.; Iturrate, E.; Jean-Louis, G.; Jones, S.A.; Onakomaiya, D.; et al. Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospitalization and Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2026881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, R. State-by-State Breakdown—Average Cost of Hospital Stays in the U.S. 2025. Available online: https://nchstats.com/average-cost-of-hospital-stays-in-us/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelBoccio, S.; Smith, D.; Hicks, M.; Lowe, P.; Graves-Rust, J.; Volland, J.; Fryda, S. Successes and Challenges in Patient Care Transition Programming: One Hospital’s Journey. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2015, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loerinc, L.B.; Scheel, A.M.; Evans, S.T.; Shabto, J.M.; O’Keefe, G.A.; O’Keefe, J.B. Discharge characteristics and care transitions of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Healthcare 2021, 9, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyer, E.H.; Brotman, D.J.; Apfel, A.; Leung, C.; Boonyasai, R.T.; Richardson, M.; Lepley, D.; Deutschendorf, A. Improving Outcomes After Hospitalization: A Prospective Observational Multicenter Evaluation of Care Coordination Strategies for Reducing 30-Day Readmissions to Maryland Hospitals. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labson, M.C. Innovative and successful approaches to improving care transitions from hospital to home. Home Healthc. Now 2015, 33, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.L., Jr.; McCauley, L.A.; Koller, C.F. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: A Report From the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. JAMA 2021, 325, 2437–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; DuGoff, E.H.; Novak, P.; Wang, M.Q. Variation of hospital-based adoption of care coordination services by community-level social determinants of health. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi-Sohi, S.; Panagioti, M.; Daker-White, G.; Giles, S.; Riste, L.; Kirk, S.; Ong, B.N.; Poppleton, A.; Campbell, S.; Sanders, C. Patient safety in marginalised groups: A narrative scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kane, M.; Agrawal, S.; Binder, L.; Dzau, V.; Gandhi, T.K.; Harrington, R.; Mate, K.; McGann, P.; Meyers, D.; Rosen, P. An Equity Agenda for the Field of Health Care Quality Improvement. NAM Perspect. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, F.; Waldhauer, J.; Wollgast, L.; Pförtner, T.-K.; Wahrendorf, M.; Haller, S.; Hoebel, J.; Wachtler, B. Temporal Dynamics of Socioeconomic Inequalities in COVID-19 Outcomes Over the Course of the Pandemic—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1605128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gurmu Dugasa, Y. Level of Patient Health Literacy and Associated Factors Among Adult Admitted Patients at Public Hospitals of West Shoa Oromia, Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Al-Ammari, M.A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.A.; Al-Taweel, M.M.; Al-Harthi, A.S. Reducing delays, improving flow: The importance of a dedicated discharge coordinator in hospital discharge planning. Cureus 2024, 16, e58634. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.