Abstract

Local Owner-Operated Retail Outlets (LOOROs) in India faced unprecedented disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic, with digital transformation emerging as both a challenge and an opportunity. The growing dominance of larger online and offline competitors, who swiftly adopted digital payments, posed a threat to traditional business models of these small neighborhood retailers. This study employs the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) framework to examine the antecedents shaping LOORO owners’ attitudes toward digital payment practices and how these attitudes influence their intention and actual adoption. A survey of 175 LOOROs in Navi Mumbai was analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The findings revealed that resource availability and customer care significantly influenced adoption, whereas competitor and customer pressure had little effect. Overall, LOORO owners demonstrated a positive outlook toward integrating digital payment systems, indicating their adaptive capacity to navigate the digital shift accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Digitalization, a knowledge-based and data-driven activity enabled by technology and communication networks, has transformed lifestyles globally [1]. This transformation has triggered a major shift, as evidenced by the gradual move from cash to digital payments [2]. At the individual level, most services, ranging from utility bills to banking and travel bookings, are now accessible and paid through mobile applications. However, despite India’s vast internet user base of 692 million [3], many still prefer to use cash, with reluctance toward digital adoption [4]. Recent studies have examined this issue through the lens of India’s digital payment system infrastructure and adoption dynamics [5].

The Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector is India’s second-largest employment generator [6], with Local Owner-Operated Retail Outlets (LOOROs), also known locally as Kirana stores, being a crucial segment of this sector. Kirana stores are neighborhood retail stores, typically under 500 sq. ft., offering convenience and familiarity [7]. LOOROs have been slow to adopt digital solutions, despite technology offering a solution to regain competitiveness [8]. However, competitive pressures and customer expectations demand digitalization [9,10].

The sudden, unexpected onset of COVID-19 pandemic amplified these pressures. Lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, and reduced foot traffic during the pandemic accelerated the use of the internet [11] and smartphone usage in emerging economies [12]. Simultaneously, digital payment practices in India gained substantial popularity and momentum during this period [13]. In a volatile context like the pandemic, contactless digital payments emerged as an important way out to thwart the spread of the virus [14]. Social distancing and concerns over cash as a potential medium for contracting the virus led to increased digital payment adoption [15,16]. Especially for LOOROs, their small shop sizes make digital payments crucial for managing transactions quickly.

Despite increasing research on digital payments in India, few studies have explored digital adoption from the perspective of small, owner-operated retailers in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most existing work is customer-focused [17] and neglects informal, small enterprises such as LOOROs. Studies rarely analyze how behavioral factors, such as empathy, customer/competitor pressures, or resource constraints, influence digital payment adoption from the standpoint of LOORO owners. Additionally, the drivers of adoption identified before the pandemic may not fully apply to the disrupted COVID-19 environment. This highlights a significant gap in understanding the unique adoption dynamics within India’s LOORO segment, which remains an understudied yet economically vital part of the MSME sector.

Our study addresses this gap by empirically analyzing data from LOORO owners in Navi Mumbai, a commercial hub with over a million residents. Its unique contribution lies in shifting the focus from customer-centric studies to exploring the perspectives of LOORO owners during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, this study investigates the impact of Available Resources (AR), Customer Pressure (CP), Perceived Pressure from Competition (PPC), and Empathy (EMP) on Attitude (ATT), Intention to Adopt (ITA), and Current Use of Digital Payments (CU). This study is structured around the following questions:

- ○

- RQ1: How do available resources, customer pressure, perceived pressure from competition, and empathy influence LOORO owners’ attitudes toward adopting digital payments?

- ○

- RQ2: How does attitude influence intention to adopt digital payments?

- ○

- RQ3: Does intention to adopt digital payments translate into current use among LOORO owners?

This study aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG 8 and SDG 9. Section 2 reviews the existing literature and theory. Section 3 formulates the hypotheses; Section 4 describes the methodology and results. Section 5 offers a discussion. Finally, Section 6 provides the implications, limitations & future scope.

2. Literature Review

2.1. LOOROs and Digital Payment Scenario in India

According to [8], a retail store can be categorized as a LOORO if it is an independent local shop where the owner manages daily operations. It typically sells FMCG products and operates during regular business hours, at least five days a week. LOOROs suffered greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic owing to their small size and physical nature. In such situations, digital payments were seen as a way to boost consumer traffic and enable LOORO owners to respond to consumers more quickly [17].

LOOROs form a significant part of MSMEs in India, and among the 63 million MSMEs in the country, 99% are micro-enterprises. Only 5 million MSMEs accept digital payments [18]. The retail industry in India accounts for approximately $790 billion, with the unorganized retail sector accounting for $695 billion [19]. This indicates the vast untapped potential of digital payments in this sector. The Indian government has been making focused efforts, such as the Digital India initiative, to promote digital payments, aiming to reduce the country’s cash dependency, thereby reducing corruption and enhancing transparency [20,21]. Many people who previously lacked access to banking facilities were able to open bank accounts with the widespread introduction of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana. Additionally, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology launched the ‘Digi Dhan Abhiyan’ campaign to encourage cashless transactions.

2.2. Stimulus–Organism–Response Model (S-O-R) Model

Several theoretical frameworks have been used in prior studies to investigate the consumers’ adoption of new technology. Based on the critical review conducted by Dahlberg et al. [22] and Pal et al. [23], studies in the domain of digital payments and Fintech are dominated by established theories such as the technology acceptance model (TAM) [24], the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT/UTAUT2) [25,26] and the diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory [27]. TAM is widely accepted [28] because it incorporates key factors such as perceived usefulness and ease of use [29]. Additionally, UTUAT/UTUAT2 was found to be extensively used in studies on consumer behavior in the FinTech domain [30,31]. Other prevalent frameworks include the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [32], theory of reasoned action (TRA) and task–technology fit (TTF).

Although several researchers turned to well-established frameworks, many others introduced new constructs because of circumstantial importance [23]. In the case of digital payments during COVID-19, especially in a developing country like India, context plays a critical role. In times of crisis, digital payments do not merely involve the acceptance of a new technology. For LOORO owners, contextual factors such as lockdowns, fear of contagion, adherence to social distancing rules, financial vulnerability and concern for customer well-being compelled them to look beyond their traditional practice of preferring cash payments. To incorporate these contextual and crisis-driven issues, adoption of a holistic and flexible approach, such as the S-O-R framework, is essential.

This study is based on Mehrabian and Russell’s Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) model [33]. The S-O-R model was thought to be better suited for our study, as it explicitly includes internal emotional states (organism) triggered by external stimuli, providing an important understanding of psychological responses of LOORO owners during a crisis like the pandemic. This was particularly true for small retailers whose adoption of digital payments during the pandemic may be due to fear of contagion and changed social conditions [28,34]. Although digital payments existed before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in India, their rapid adoption may have been accelerated for external reasons. These drivers precede internal cognitive evaluations (attitudes towards digital payments), resulting in behavioral responses (intent to adopt and use). The S-O-R model has been used by prior researchers in various contexts, such as mobile banking [35], mobile applications [36], green marketing and innovation [37], and drone deliveries [38], to name a few. Several studies have also applied the theory to explain digital payment adoption, including P2P payments [39], facial recognition payments [40], digital payments [41] and WhatsApp payments [42]. These examples demonstrate the versatility and adaptability of the S-O-R framework.

2.3. Available Resources

LOOROs, often limited by scarce external and internal resources, frequently struggle to invest in digital tools that could provide them with a competitive edge. Poor physical and digital infrastructure, limited access, unreliability of digital technologies, and high costs hinder the adoption of digital tools by small retailers [10]. A study in Jaipur, India [43], found that about 60% of the sample had not adopted any form of digital payment, highlighting the low adoption rate among small businesses. Another study in Bangalore indicated that only 48% of small merchants accepted digital payments, suggesting that 52% avoided digital platforms [44]. The reasons for low digital payment adoption include reliance on cash transactions, high operating costs, and a lack of digital skills. Challenges such as low cash flow and additional charges associated with digital payments further complicate small merchants’ attitudes towards digital payment systems. Although LOOROs have some control over their internal resources, certain external factors may restrict their ability to adopt digital technologies [45,46]. Consequently, we view available resources as the primary stimulus, reflecting how much a LOORO perceives resource constraints as limiting their capacity to adopt digital payments [47].

2.4. Customer Pressure

Customer pressure is considered a significant predictor of fintech adoption among small retailers, mainly due to the increasing expectation for efficient, convenient and trackable transactions that digital technology can provide [48]. Customer demand hastens the uptake of Industry 4.0 technologies, underscoring the decisive role of customer involvement in digital technology adoption [49,50]. The relationship between customer pressure and digitalization is complex and affects various aspects of business operations and strategies. Given their high levels of customer interaction, LOOROs are particularly influenced by the need to respond to evolving customer expectations and pressures [51,52].

2.5. Perceived Pressure from Competitors

The perceived pressure from competitors is evident in how businesses view their development in relation to others and how they anticipate external pressures to maintain a competitive advantage [45,53]. According to Porter and Millar [54], adopting innovation can enable organizations to shift competition norms. This pressure is evident in many sectors where digital transformation is essential for improved performance. Therefore, increased adoption of digital technologies often occurs in industries, such as LOOROs, where competitiveness is intensifying [55].

2.6. Empathy

Empathy is the ability to share the emotions or experiences of another person by imagining what it would be like to be in their shoes [56]. Empathy is crucial in retail for understanding user needs. LOORO owners need to be able to put themselves in the user’s shoes to grasp their perspective [57]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns were enforced and limited shopping was permitted under strict social distancing guidelines, customer experiences were reshaped by the sensitivity of businesses that demonstrated empathy and showed care and concern [16]. Therefore, the fourth stimulus considered in this study is empathy towards customers.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Influence of Availability of Resources on Attitude

One of the factors influencing the adoption of digital payments by LOOROs is resource availability, which encompasses a business’s ability to invest in digital infrastructure and the knowledge required to operate and perform digital payments [10]. Alamsyah et al. [58] found that adequate infrastructure facilitates the use of digital payment methods. Golitsis et al. [59] identified inadequate payment infrastructure as a significant barrier, suggesting that resource availability may be crucial for the successful implementation of digital payments. Furthermore, the affordability of fees on digital platforms and the merchants’ digital literacy help overcome obstacles to adoption. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The availability of resources has a positive influence on the attitude towards digital payment methods.

3.2. Influence of Customer Pressure on Attitude

Customer pressure relates to the perception of customers’ expectations of digitalization [60]. Customer expectations can influence retail businesses to adopt technology for digitalization [52]. To maintain a competitive position, LOOROs are more likely to adopt payment technologies and innovations when they perceive pressure from their customers [61]. According to Kumar et al. [62], 98.1% of respondents in Bengaluru’s suburban area preferred digital wallet services. As more people opt for digital payment methods, LOOROs are compelled to adopt digital payments. Therefore, we can hypothesize that,

H2.

Customer pressure towards digitalization has a positive influence on the attitude towards digital payment methods.

3.3. Influence of Perceived Competitiveness Towards Customers on Attitude

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing number of people sought contactless payment options, and digital solutions such as UPI payments became more convenient [63,64]. During the crisis, many businesses had no choice but to switch to digital payments as their competitors offered contactless payment options. However, small stores are generally slower to adopt digital technologies because of low digital literacy and transaction costs [65]. Hence, LOOROs were forced to explore digital payment options to remain competitive [10]. This change is part of a larger trend in which digital payments are no longer optional but necessary. Hence, we hypothesize:

H3.

Perceived Competitiveness towards digitalization has a positive influence on the attitude towards digital payment methods.

3.4. Influence of Empathy Towards Customers on Attitude

An organization’s ability to provide services tailored to customer needs is linked to empathy [56]. Understanding customers’ expectations, as noted by Bahadur et al. [66], aligns with a shop owner’s empathy, as it helps them anticipate their needs. Previous studies have shown that customer satisfaction increases when frontline service staff demonstrate empathy and care [67]. Conversely, a lack of empathy has been found to affect customer engagement negatively [67,68,69]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4.

Empathy towards customers has a positive influence on the attitude towards digital payment methods.

3.5. Influence of Positive Attitude Towards Digitalization on the Intention to Use Digital Payment Methods

The four dimensions of the Stimulus, namely available resources, perceived pressure from competitors, customer pressure, and empathy, cause the organism’s (emotional) reactions, influencing the owner’s attitude toward digital payment options [47]. Although attitude does not directly influence actual behavior, it affects usage through the behavioral intention to use digital payments [26,32]. Therefore, the owner’s attitude toward digital payment options shapes their intent to use them [70]. To support this argument, we propose the following hypothesis.

H5.

Attitude towards digitalization has a positive influence on the intention to adopt digital payment methods.

3.6. Influence of Intention to Use Digital Payment Options on Actual Usage

Prior studies indicate that the intention to use influences actual usage behavior [26,32,71]. For example, a study conducted during the demonetization period in India revealed that behavioral intention significantly influenced the use of digital payments [72]. In line with the S-O-R framework, once the organism is exposed to stimuli, the actual behavior of the organism, that is, the LOORO owner, is affected by the behavioral intentions they form. Therefore, it directly impacts the usage of digital payments [47]. Hence, we hypothesize:

H6.

The intention to adopt digital payment methods has a positive influence on the current usage of digital payment methods.

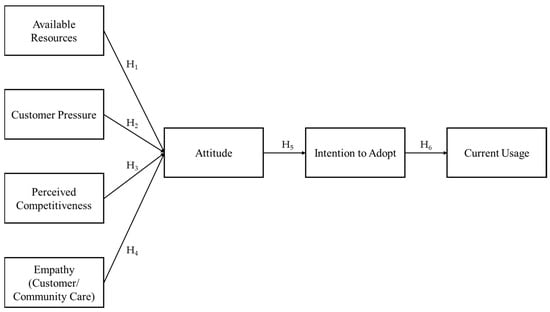

The conceptual model developed for this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model (Author’s own work).

4. Methods

4.1. Research Instrument

A quantitative method was used in this study. Cross-sectional data were collected in person through a questionnaire survey. Structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was utilized to validate the measurement model and test the hypotheses. Validated questions from prior studies were included in the questionnaire used in this research. Additionally, the content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by experts in the field. The reflective constructs were measured using a survey questionnaire (Table 1) on a five-point Likert scale. Before conducting the primary survey, a pilot test was conducted with 20 LOORO owners to evaluate the clarity, reliability, and understanding of the items. Minor wording changes were made based on their feedback before the final version of the questionnaire was released.

Table 1.

Research Instrument.

4.2. Data Collection

Data was collected by personally visiting the kirana stores (LOOROs). Convenience sampling was used because there was no formal or usable sampling frame for LOOROs, and mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 period made probability-based sampling impractical. Survey forms were distributed in the areas of Nerul, Seawoods, Sanpada, and Vashi in Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. The criteria used for selecting the shops to be surveyed are that the establishment must be independently owned, with the owner actively involved in day-to-day store operations. The LOORO owner was allowed to respond in either Hindi (the local language) or English. The questionnaire went through a thorough translation and validation process. The original English version was translated into Hindi, following Sperber’s [74] forward–backward translation guidelines, to ensure semantic and conceptual equivalence. Two bilingual experts reviewed the translations, and any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Content validity was further confirmed by three domain experts who assessed item clarity, relevance, and alignment with construct definitions. The survey was conducted over four months, starting in May 2021, during the aftermath of India’s severe second COVID-19 wave. During this period, mobility restrictions, increased health concerns, and reliance on contactless transactions remained significant, directly influencing the perceptions and adoption of digital payment practices among LOORO owners.

A total of 175 completed responses were analyzed for the study, and 42 shops either refused to participate or did not respond, resulting in a response rate of 80.65%. A mean replacement algorithm was used to handle the missing data. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 2. Ninety-two percent of the respondents were male, and the rest were female. Eighty-four percent of the respondents were between the ages of 18 and 45.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.3.1. Measurement Model Analysis

The assessment of indicator reliability depends on outer loadings. Any item with an outer loading below 0.4 should be omitted, while items with outer loadings between 0.4 and 0.7 should only be discarded if doing so improves Cronbach’s alpha and Composite reliability. A Cronbach’s alpha above 0.6 is considered acceptable for explanatory analysis [75], although values between 0.5 and 0.6 indicate moderate reliability [76]. A Composite reliability between 0.6 and 0.7 is acceptable for explanatory analysis, while values between 0.7 and 0.9 are regarded as satisfactory [75]. The outer loading values of AR_4, PPC_2, CP_1, and ATT_5 were below 0.6; therefore, they were removed from the model to ensure good composite reliability and convergent validity. These items showed weak indicator reliability and did not adequately represent their constructs, as maintaining them in a negative state influenced construct reliability. Their removal enhanced the overall measurement quality, leading to higher composite reliability and AVE values for the retained indicators (Table 3).

Table 3.

Measurement model analysis.

Composite Reliability (CR) ranged from 0.768 to 0.947, which is well above the threshold value of 0.70. Convergent validity is the extent to which two measures of a construct that are theoretically related are, in fact, related [77]. An average variance extracted (AVE) greater than 0.5 for each construct indicates that the model satisfies convergent validity [78]. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for the constructs ranged from 0.526 to 0.856, which is well above the threshold value of 0.50, confirming convergent validity. The results of the measurement model analysis are shown in Table 3.

Discriminant validity assesses whether concepts or measurements that should not be related are indeed unrelated [77]. The questionnaire was tested for divergence using the discriminant validity method, as outlined in the Fornell–Larcker criteria. In the result matrix, the diagonals represent the square root of the AVE values. These diagonal values should exceed any other value in their respective row and column to demonstrate discriminant validity [75] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

4.3.2. Structural Model Analysis

The first step in assessing the structural model is to check for collinearity among the constructs. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values greater than 3 suggest the possibility of multicollinearity, and values above 5 indicate its presence. All constructs have VIFs below the minimum threshold of 5 and remain under 3, indicating no multicollinearity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multicollinearity testing—Inner VIF values.

Using the bootstrapping algorithm, the path coefficients are calculated from t-statistic values based on 5000 subsamples. Table 6 shows the t-values and path coefficients of the constructs, emphasizing the significant relationships.

Table 6.

Hypothesis Testing.

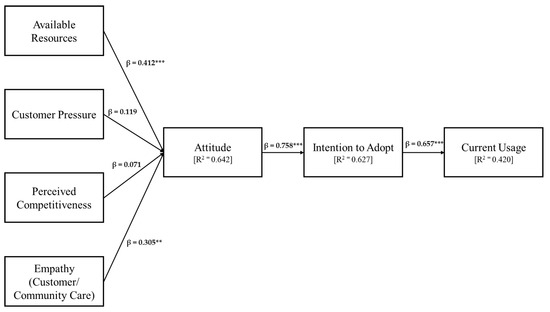

The results supported four out of six hypotheses (Figure 2). Available resources (β = 0.412, p < 0.001) and empathy (β = 0.305, p < 0.01) significantly influenced attitude. However, perceived pressure from competitors (β = 0.071, p > 0.05) and customer pressure (β = 0.119, p > 0.05) did not have a significant effect on attitude. Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 4 are supported, while hypotheses 2 and 3 are not. The intention to adopt was significantly affected by attitude (β = 0.758, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 5. Finally, the intention to adopt significantly influenced current usage (β = 0.657, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 6.

Figure 2.

Structural Model Results (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

The R2 values, also known as the coefficients of determination, indicate the proportion of variance in endogenous constructs that is explained by exogenous constructs [75]. The interpretation of R2 values varies across studies. Values from 0.33 to 0.67 signify moderate influence, while values from 0.19 to 0.33 denote weak influence [79]. Table 7 presents the R2 values obtained. The R2 for Attitude was 0.642, for Intention to Adopt was 0.42, and for Current Usage was 0.627, all suggesting moderate influence on the respective endogenous constructs.

Table 7.

R2 Values.

5. Discussion

The study observed a significant influence of available resources on positive attitudes toward digital payment options. These results are consistent with those of Bollweg et al. [80] and Delgado-de Miguel et al. [81]. To accept payments via the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in India, the most popular e-payment method, LOOROs must have devices capable of running UPI apps, such as Paytm, PhonePe and Google Pay, along with internet connectivity for seamless transactions and scannable QR codes. The results indicate that the availability of such resources affected LOORO’s attitude toward digital payments during the COVID-19 pandemic. This result aligns with prior research, which shows that access to digital infrastructure remains the strongest factor influencing the adoption of digital payment systems [82]. India’s rapid growth in digital payments is closely linked to resource accessibility, driven by policy efforts to expand broadband and digital services for small merchants [83]. This finding also aligns with cross-country studies conducted during the pandemic, which consistently show that resource availability, device readiness, and connectivity significantly impact SME’s digital payment adoption [84,85].

This study found that perceived pressure from competitors and customers did not significantly influence the attitude of LOOROs towards adopting digital payment practices, contradicting Bollweg et al. [80], who found that perceived pressure from competitors and customers was a significant factor. This aligns with Franco et al. [86], who highlight the critical influence of customer pressure in the digitalization of SMEs. Their view finds support in a study conducted by Khan & Ali [53], who found that consumer pressure was a key driver. However, the same study found that competitive pressure had no significant effect on the adoption of digital payment applications. These results must be cautiously viewed in the light of a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, where health concerns and convenience dominated adoption decisions rather than social influences or competitive pressure. For example, in China, research conducted during COVID-19 showed that perceived benefits were crucial, suggesting that perceptions were shaped mainly by contexts rather than competitive or social pressure [34]. Similarly, a study in India found that while digital payment adoption during COVID-19 was influenced by factors such as performance expectancy, ease of use, and trust, social factors did not play a role [87]. Bhatia et al. also found that factors such as perceived risk and expectation played more dominant roles in digital payment use during COVID-19, indicating that intrinsic drivers outpaced social pressure drivers [88]. This suggests individuals value risk mitigation and system trust over external social pressure from competitors or customers. Similar mixed or inconclusive results have been reported in other emerging markets, where competition did not consistently promote digital payment adoption among SMEs [89]. These findings could also be attributed to the fact that most respondents have already adopted digital payment options in their businesses; therefore, perceived pressure from competitors and customers does not significantly influence their attitude.

Furthermore, to distinguish themselves from competitors, LOOROs often focus on creating unique customer experiences. Therefore, customer loyalty remains vital, as customers may continue to patronize a specific retail outlet despite the payment options offered by competing LOOROs, prioritizing factors such as familiarity and proximity. Additionally, India’s relationship-based retail culture, where customer loyalty is built on long-term relationships rather than payment methods, diminishes the influence of competitive pressure on the adoption of payment systems.

These contradictory findings may also be related to the Indian cultural context, where customer payment preferences are diverse: younger consumers often expect digital payments, whereas older or less tech-savvy customers prefer cash. Consequently, LOOROs may not face consistent customer-driven pressure to adopt digital payment methods.

Finally, it is also possible that measures for customer and competitive pressures in normal business contexts might not have captured the nuanced pandemic-driven behavioral factors. The pandemic introduced exceptional circumstances like enforced lockdowns and altered consumer priorities, which may have diluted normal pressure effects [90]. Thus, we consider failure to modify measurement scales to include COVID-specific contextual pressures could have led to insignificant findings.

We found that empathy significantly influenced attitudes toward adopting digital payments. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s challenges and suffering fostered feelings of empathy for one another. Studies agree that having empathic concern for those most at risk of contracting the virus increases the desire to adopt and uphold social precautions [16,91,92]. They also found that traits such as empathy correlate with the voluntary adoption of social distancing. Since the use of digital payments encourages social distancing, this aligns with the findings of our study. As the pandemic compelled consumers to depend more on contactless payments and e-commerce, local businesses recognized the need to offer digital payment options to their customers, who were concerned about social distancing and safety. Findings from other Asian countries, such as China [84], also suggest that broader prosocial motivations and perceived safety benefits played a role in technology adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study found positive attitudes towards digitalization, which significantly influenced the intention to adopt digital technologies. This aligns with many previous studies [93,94,95], which have shown that attitude has a strong impact on intent. LOOROs are more likely to implement these technologies because they view digital payments as an effective way to improve customer experience, streamline transactions, and stay competitive. Similar relationships between attitude and intention have been observed among SMEs in other emerging economies that have adopted mobile payments [70].

Furthermore, the results revealed that the intention to provide digital payments has a positive relationship with the current use of such technology. These findings align with those of Bollweg et al. [80]. This is further supported by Chaveesuk et al. [96] and Musyaffi et al. [97]. Comparable evidence from Indonesia confirms that intention is a key determinant of QR-based mobile payment use among MSME merchants [70].

6. Implications, Limitations and Future Scope

6.1. Theoretical Implications

LOOROs in India faced unprecedented challenges due to repeated lockdowns and reduced foot traffic during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, digital payments proved to be a silver lining, helping them manage the crisis as contactless transactions became possible, ensuring safety for both employees and customers. This study captures a critical moment when India adopted disruptive technology, paving the way for transparent and convenient transactions that continued even after the pandemic subsided. Our study offers a unique contribution to the body of knowledge in the context of a densely populated metropolis like Mumbai, capturing the perspectives of LOORO owners during the intense lockdown period and shortly afterwards. It also provides a foundation for researchers to understand the factors from the perspective of a developing economy that supported the acceptance of digital technology amid a crisis.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings that resource availability significantly influences local LOORO’s adoption of digital payments have important policy implications. First, by educating LOORO owners about the benefits of digital payments, policymakers should focus on initiatives that foster a positive attitude towards digital payments. These initiatives may include awareness campaigns, training sessions, tools, and support needed to improve their knowledge of digital payment technology, which can enhance their chances of adopting digital payments. To build trust and confidence among small businesses and customers alike, governments can establish clear regulatory standards that ensure data privacy and security in digital payment systems. Adoption rates can be significantly increased by offering incentives to firms that use digital payments, such as lower transaction fees or tax benefits.

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Scope

Our study has several limitations. First, the study only used data from Navi Mumbai, a single Indian city, which limits the applicability of the findings to other cities or areas where factors influencing digital payment adoption may vary. Second, convenience sampling, although practical during the pandemic, may reduce the sample’s representativeness and introduce regional or socioeconomic bias. While we attempted to keep participants homogeneous and minimize bias, participation primarily depended on proximity and the willingness of LOORO owners. Third, although the sample size was sufficient for PLS-SEM analysis, a larger and more diverse sample could provide more profound insights into the factors influencing digital payment adoption. Additionally, since the questionnaire focused on digital payment practices, social desirability bias may have occurred, with some LOORO owners possibly overstating positive attitudes or behaviors to conform to expected norms. Lack of COVID-contextual scales could have reduced the sensitivity of the measurement and might have contributed to the insignificant results. Finally, most respondents belonged to essential service categories, such as general stores, pharmacies, and food vendors. Owing to travel restrictions, the study was mostly limited to urban neighborhoods.

Developing countries like India are going through rapid digitalization, transforming public mindset towards contactless payments and boosting the national economy. Small businesses such as LOOROs operate within this continuously evolving digital ecosystem. Thus, there is considerable potential for future research. First, there is always a scope to examine new drivers leading to customer intent to adopt digital payments. Some likely drivers include community influence, store loyalty, visibility anxiety, inclusivity and modernity signaling, and word of mouth among consumers, which might impact the adoption of digital payments. Additionally, future studies should consider moderating factors such as education level, digital literacy, and access to technology, which may affect the adoption of digital payment systems. Second, longitudinal studies may be conducted to understand whether the relationship between the factors considered and the adoption patterns observed during COVID-19 persists. Such studies would help us understand whether the crisis-induced findings were temporary reactions or long-term behavioral shifts. Furthermore, researchers could explore the extension of S-O-R theory in other digital payment studies subjected to context-specific stimuli, such as unexpected regulatory or policy changes. As the current study is quantitative, a qualitative/mixed-methods approach could be employed subsequently, involving interviews with LOORO owners to gain a better understanding of their motivation and hesitations in adopting digital payment methods. Understanding the possible discrepancies and associations between constructs in different settings may offer valuable and interesting insights. Hence, comparative review studies between developed and developing countries may be conducted in the future to investigate situation-specific adoption behaviors brought forth by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.L. and B.M.; Data curation, B.M. and A.O.M.; Formal analysis, A.K.L., B.M. and A.O.M.; Investigation, A.K.L. and A.O.M.; Methodology, B.M. and A.O.M.; Project administration, A.K.L.; Software, B.M. and A.O.M.; Supervision, A.O.M.; Validation, A.O.M.; Writing—original draft, A.K.L. and B.M.; Writing—review and editing, B.M. and A.O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in full compliance with ethical research guidelines. It qualifies for exemption from formal ethical approval as per the institutional circular by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of Kasturba Medical College and Kasturba Hospital under the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) (ECR/146/Inst/KA/2013/RR-19), on 14 December 2021, DHR registration number EC/NEW/INST/2019/374).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all survey respondents of the study prior to collecting the data.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LOORO | Local Owner-Operated Retail Outlets |

| S-O-R | Stimulus–Organism–Response |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| MSME | Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises |

| AR | Available Resources |

| CP | Customer Pressure |

| PPC | Perceived Pressure from Competition |

| EMP | Empathy |

| ATT | Attitude |

| ITA | Intention to Adopt |

| CU | Current Use of Digital Payments |

| FMCG | Fast Moving Consumer Goods |

References

- Wang, K.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Xue, K.; Wang, C.; Peng, M. Digital Resilience in the Internationalization of Small and Medium Companies: How Does It Work? J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 1458–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudin, M.N.; Shkodinskii, S.V.; Usmanov, D.I. Key Trends and Regulations of the Development of Digital Business Models of Banking Services in Industry 4.0. Financ. Theory Pract. 2021, 25, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. India’s Growing Internet Connectivity. May 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/262966/number-of-internet-users-in-selected-countries/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Shree, S.; Pratap, B.; Saroy, R.; Dhal, S. Digital Payments and Consumer Experience in India: A Survey Based Empirical Study. J. Bank. Financ. Technol. 2021, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.; Agarwal, B.; Nautiyal, N. Financial Technology Adoption—A Case of Indian MSMEs. Financ. Theory Pract. 2022, 26, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A. Covid-19 Affect on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Times of India Blog. 23 September 2020. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/agyeya/covid-19-affect-on-micro-small-and-medium-enterprises-msmes/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- The Telegraph Online. Little guy stands tall. The Telegraph, 27 July 2023. Available online: https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/the-friendly-neighbourhood-kirana-is-going-nowhere/cid/1845080 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Bollweg, L.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M.; Weber, P. Carrot-or-Stick: How to Trigger the Digitalization of Local Owner Operated Retail Outlets? In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärsch, S.; Bollweg, L.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M.; Weber, P.; Wulfhorst, V. Local Shopping Platforms–Harnessing Locational Advantages for the Digital Transformation of Local Retail Outlets: A Content Analysis. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI 2019), Siegen, Germany, 24–27 February 2019; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2019/track06/papers/5/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Seethamraju, R.; Diatha, K.S. Adoption of Digital Payments by Small Retail Stores. In Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Sydney, Australia, 3–5 December 2018; UTS ePRESS: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britwum, F.; Anin, S.K.; Agormedah, E.K.; Quansah, F.; Srem-Sai, M.; Hagan, J.E.; Schack, T. Assessing Internet Surfing Behaviours and Digital Health Literacy among University Students in Ghana during the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2023, 3, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, C. From Necessity to Excess: Temporal Differences in Smartphone App Usage–PSU Links During COVID-19. COVID 2025, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, T.; Suresha, B.; Prakash, N.; Vazirani, K.; Krishna, T.A. Digital Financial Literacy among Adults in India: Measurement and Validation. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2132631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttena, R.K.; Atmaja, F.T.; Wu, C.H.J. COVID-19 crisis–coping up strategies of companies to sustain in markets. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2024, 18, 1366–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, G.O.C.; Balunywa, W.; Mwebaza Basalirwa, E.; Ngoma, M.; Mpeera Ntayi, J. Contactless Digital Financial Innovation and Global Contagious COVID-19 Pandemic in Low Income Countries: Evidence from Uganda. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2023, 11, 2132631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Kim, J.; Min, J.; Hernandez-Calderon, A. Effects of Retailers’ Service Quality and Legitimacy on Behavioral Intention: The Role of Emotions during COVID-19. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Kumar, S.; Verma, P.; Maiti, M. Determinants of Digitalization in Unorganized Localized Neighborhood Retail Outlets in India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, A. If We Are to Drive Digital Adoption, Growth Will Come from MSMEs: FSS. DATAQUEST. 2022. Available online: https://www.dqindia.com/if-we-are-to-drive-digital-adoption-growth-will-come-from-msmes-fss/amp/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- RETAIL-IBEF. India Brand Equity Foundation. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibef.org/download/Retail-January-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Deb, M.; Agrawal, A. Factors Impacting the Adoption of M-Banking: Understanding Brand India’s Potential for Financial Inclusion. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2017, 11, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, N. Modi urges country to become a cashless society. The Hindu, 17 November 2021. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/article60596527.ece (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Dahlberg, T.; Guo, J.; Ondrus, J. A critical review of mobile payment research. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; De’, R.; Herath, T.; Rao, H.R. A review of contextual factors affecting mobile payment adoption and use. J. Bank. Financ. Technol. 2019, 3, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, E.; Solikin, I.; Purnomo, B.S. A review of digital payment adoption in Asia. Adv. Int. J. Bus. Entrep. SMEs 2022, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryyev, G.; Spyridou, A.; Yeh, S.; Lo, C.C. Factors of digital payment adoption in hospitality businesses: A conceptual approach. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 29, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Chun T’ing, L.; Chea Yee, K.; Wen Huey, A.; Joe In, L.; Chyi Feng, P.; Jia Yi, T. What drives the adoption of mobile payment? A Malaysian perspective. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 25, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odei-Appiah, S.; Wiredu, G.; Adjei, J.K. Fintech use, digital divide and financial inclusion. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2022, 24, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. How does the pandemic facilitate mobile payment? An investigation on users’ perspective under the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.; Pillai, S.S. Role of mobile banking servicescape on customer attitude and engagement: An empirical investigation in India. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shah, A. Revisiting food delivery apps during COVID-19 pandemic? Investigating the role of emotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya Rivas, A.; Liao, Y.K.; Vu, M.Q.; Hung, C. Toward a comprehensive model of green marketing and innovative green adoption: Application of a stimulus-organism-response model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Rodriguez-López, M.E.; Higueras-Castillo, E.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Drones in food delivery: An analysis of consumer values and perspectives. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 28, 1744–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia-Diéguez, A.; Velicia-Martín, F.; Aguayo-Camacho, M. Predicting FinTech innovation adoption: The mediator role of social norms and attitudes. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Pan, L.Y. Smile to pay: Predicting continuous usage intention toward contactless payment services in the post-COVID-19 era. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, H.; Glavee-Geo, R.; Alharthi, M.; Doszhan, R.; Suyunchaliyeva, M.M. Exploring trust and outcome expectancy in FinTech digital payments: Insights from the stimulus-organism-response model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2025, 43, 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.F.; Kirmani, M.D.; Bin Sabir, L.; Faisal, M.N.; Rana, N.P. Consumer resistance to WhatsApp payment system: Integrating innovation resistance theory and SOR framework. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025, 43, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, E.; Malick, B.; Sheth, K.; Trachtman, C. What Explains Low Adoption of Digital Payment Technologies? Evidence from Small-Scale Merchants in Jaipur, India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, T.; Prakash, N. Determinants of Adoption of Digital Payment Services among Small Fixed Retail Stores in Bangalore, India. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2022, 28, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, R.; Day, J. Determinant Factors of E-Commerce Adoption by SMEs in Developing Country: Evidence from Indonesia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparling, L.; Toleman, M.; Cater-steel, A. SME Adoption of E-Commerce in the Central Okanagan Region of Canada Review of e-Commerce Adoption Literature. In Proceedings of the 18th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia, 5–7 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bollweg, L.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M.; Weber, P. Drivers and barriers of the digitalization of local owner operated retail outlets. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 32, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abueid, A.I.; Mohammad, A.A.S.; Almomani, H.M.; Mohammad, S.I.; Vasudevan, A.; Almohaimmeed, B.M.; Al Oraini, B.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Saraireh, S. Strategies for Successful Digital Transformation in the Jordanian Banking Sector: Leveraging FinTech for Enhanced Customer Engagement. In Artificial Intelligence, Sustainable Technologies, and Business Innovation: Opportunities and Challenges of Digital Transformation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.K.; Sahoo, S.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, P.P.; Ilahi, F. Impact of institutional pressures and security on blockchain technology adoption and organization performance: An empirical study. J. Technol. Transf. 2025, 50, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H.C.; Yu, M. Proposing a four-dimension model to study the drivers of Industry 4.0 technology adoption and service innovation from a moderated mediation perspective. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital Business Strategy: Toward a next Generation of Insights. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strønen, F. Drivers for Digitalization in Retail and Service Industries. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, ECMLG 2020, Online, 26–27 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Ali, A. Factors Affecting Retailer’s Adoption of Mobile Payment Systems: A SEM-Neural Network Modeling Approach. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 103, 2529–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Millar, V.E. How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage. Harvard Buiness Rev. 1985, 49, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L. Post-Adoption Variations in Usage and Value of e-Business by Organizations: Cross-Country Evidence from the Retail Industry. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 61–84. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23015765 (accessed on 10 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A. The Service-Quality Puzzle. Bus. Horiz. 1988, 31, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrell, T. User Empathy in the Early Phase of Product–Service Systems Development. In Empathic Service Design; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2025; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, F.; Usman, I.; Lestari, Y.D. The influence of infrastructure quality on usage smart mobile applications and digital payments. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golitsis, P.; Hornichna, Y.; Szamosi, L. Cashless transformation and consumer spending during extreme crises: Evidence from Ukraine. J. East-West Bus. 2025, 31, 382–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollweg, L.; Siepermann, M.; Sutai, A.; Lackes, R.; Weber, P. Digitalization of Owner Operated Retail Outlets: The Role of the Perception of Competition and Customer Expectations. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.; Deng, H.; Corbitt, B. Evaluating the Critical Determinants for Adopting E-Market in Australian Small-and-Medium Sized Enterprises. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Mehrotra, I.; Ahmed, K.A.A. Determinants of Digital/Mobile Payment Services Adoption in India. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2021, 8, 845–857. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR2107718.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Chaturvedi, A.; Ranjan, S. Impact of Digital Payment Trends: Unraveling Consumer Behavior Patterns (Pre-and Post-COVID-19). In Microfinance, Financial Innovation, and Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Economics; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, V.; Padmavathy; Indira, D. Perception of small retail stores towards digital payment. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 3007, p. 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanigan, J.; Reddy, N.S.; Maity, M.; Sethuraman, P.; Rajesh, J.I. An integrated framework for understanding innovative digital payment adoption and continued usage by small offline retailers. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2462442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, W.; Aziz, S.; Zulfiqar, S. Effect of Employee Empathy on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty during Employee–Customer Interactions: The Mediating Role of Customer Affective Commitment and Perceived Service Quality. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1491780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Comer, L.B.; Dubinsky, A.J.; Schafer, K. The Role of Emotion in the Relationship between Customers and Automobile Salespeople. J. Manag. Issues 2011, 23, 206–226. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23209226 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Gorry, G.A.; Westbrook, R.A. Once More, with Feeling: Empathy and Technology in Customer Care. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, R.; Krush, M.T. Salesperson Empathy, Ethical Behaviors, and Sales Performance: The Moderating Role of Trust in One’s Manager. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2015, 35, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irianto, A.B.P.; Chanvarasuth, P. Drivers and Barriers of Mobile Payment Adoption Among MSMEs: Insights from Indonesia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, E.; Sjarief, R.; Dawan, A.; Kurniawan, S.; Pertiwi, N.; Zahra, N. The Acceptance of Electronic Payment Among Urban People: An Empirical Study of the C-Utaut-Irt Model. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 2023, 11, e559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivathanu, B. Adoption of Digital Payment Systems in the Era of Demonetization in India: An Empirical Study. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollweg, L.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M.; Weber, P. Digitalization of Local Owner-Operated Retail Outlets: Between Customer Demand, Competitive Challenge and Business Persistence. In Proceedings of the WI2020 Zentrale Tracks, Potsdam, Germany, 8–11 March 2020; pp. 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, A.D. Translation and Validation of Study Instruments for Cross-Cultural Research. Proc. Gastroenterol. 2004, 126, S124–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.; McMurray, I.; Brownlow, C. SPSS Explained; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, M.; Shuttleworth, M. Convergent and Discriminant Validity. Explorable. 2009. Available online: https://explorable.com/convergent-validity (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, H.; Verhagen, T.; Creemers, M. Understanding Online Purchase Intentions: Contributions from Technology and Trust Perspectives. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollweg, L.; Baersch, S.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M.; Weber, P. The Digitalization of Local Owner-Operated Retail Outlets: How Environmental and Organizational Factors Drive the Use of Digital Tools and Applications. In Proceedings of the Business Information Systems, Online, 14–17 June 2021; pp. 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-de Miguel, J.F.; Menchero, T.B.L.; Esteban-Navarro, M.Á.; García-Madurga, M.Á. Proximity Trade and Urban Sustainability: Small Retailers’ Expectations towards Local Online Marketplaces. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafif, H.; Ouboumlik, A.; Touhami, N.O. Digital Divide and the Adoption of Digital Payments in Mena Countries: Challenges and Opportunities for Financial Inclusion. Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2025, 20, 291–318. [Google Scholar]

- PWC India. The Indian Payments Handbook (2020–2025); PWC India: Bhopal, India, 2020; Available online: https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/consulting/financial-services/fintech/payments-transformation/the-indian-payments-handbook-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Cao, T. The Study of Factors on the Small and Medium Enterprises’ Adoption of Mobile Payment: Implications for the COVID-19 Era. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 646592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Digitalizing SMEs to Boost Competitiveness; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099515009292224182/pdf/P17608901a9db608909f5b02980d48c4e28.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Franco, M.; Godinho, L.; Rodrigues, M. Exploring the Influence of Digital Entrepreneurship on SME Digitalization and Management. Small Enterp. Res. 2021, 28, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandru, P.; Chendragiri, M.; Senthilkumar, S.A. Factors affecting the adoption of mobile payment services during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application of extended UTAUT2 model. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2025, 16, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Singh, N.; Liebana-Cabanillas, F. Intermittent continued adoption of digital payment services during the COVID-19 induced pandemic. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 2905–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, F.; Le, V.; Masli, E.K. Determinants of digital technology adoption in innovative SMEs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H. How successful countries are in promoting digital transactions during COVID-19. J. Econ. Stud. 2022, 49, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galang, C.M.; Johnson, D.; Obhi, S.S. Exploring the Relationship Between Empathy, Self-Construal Style, and Self-Reported Social Distancing Tendencies During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 588934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nockur, L.; Böhm, R.; Sassenrath, C.; Petersen, M.B. The Emotional Path to Action: Empathy Promotes Physical Distancing and Wearing of Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the Attitude and Intention to Use Smartphone Chatbots for Shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.W.; Kim, J.K. Factors That Influence Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-González, S.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Predicting the Intentions to Use Chatbots for Travel and Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 24, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaveesuk, S.; Khalid, B.; Chaiyasoonthorn, W. Digital Payment System Innovations: A Marketing Perspective on Intention and Actual Use in the Retail Sector. Innov. Mark. 2021, 17, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyaffi, A.M.; Sari, D.A.P.; Respati, D.K. Understanding of digital payment usage during COVID-19 pandemic: A study of UTAUT extension model in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. 2021, 8, 475–482. Available online: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO202115563442861.page (accessed on 20 April 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.