Abstract

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, disrupts human cellular pathways through complex protein–protein interaction, contributing to disease progression. As the virus has evolved, emerging variants have exhibited differences in transmissibility, immune evasion, and pathogenicity, underscoring the need to investigate their distinct molecular interactions with host proteins. In this study, we constructed a comprehensive SARS–CoV–2–human protein–protein interaction network and analyzed the temporal evolution of pathway perturbations across different variants. We employed computational approaches, including network-based clustering and functional enrichment analysis, using our custom-developed Python (v3.13) pipeline, BioEnrichPy, to identify key host pathways perturbed by each SARS-CoV-2 variant. Our analyses revealed that while the early variants predominantly targeted respiratory and inflammatory pathways, later variants such as Delta and Omicron exerted more extensive systemic effects, notably impacting neurological and cardiovascular systems. Comparative analyses uncovered distinct, variant-specific molecular adaptations, underscoring the dynamic and evolving nature of SARS-CoV-2–host interactions. Furthermore, we identified host proteins and pathways that represent potential therapeutic vulnerabilities, which appear to have co-evolved with viral mutations.

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused a global health crisis since its emergence in late 2019, leading to significant morbidity, mortality, and socio-economic challenges [1]. As the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), SARS-CoV-2 employs a complex array of molecular interactions to hijack human cellular machinery, enabling viral replication and dissemination [2]. Central to this process are the interactions between viral proteins and human host proteins, which disrupt key cellular pathways and contribute to the diverse clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [3].

SARS-CoV-2 primarily enters the human body through the respiratory tract via the inhalation of virus-containing droplets or aerosols. The viral spike (S) protein is essential for host cell entry, as it binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is abundantly expressed on the epithelial cells of the lungs, nasal passages, and various other tissues [4]. This interaction is further enhanced by host proteases such as TMPRSS2, which cleave the spike protein to facilitate membrane fusion [5]. Once inside the host cell, the virus releases its RNA genome and exploits the host’s cellular machinery to replicate and produce new virions, resulting in infection and, in certain cases, severe immune responses that exacerbate disease progression. Over time, SARS-CoV-2 has evolved into multiple variants due to genetic mutations, some of which have markedly influenced its transmissibility, immune evasion capabilities, and disease severity [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has designated several major variants of concern (VOCs), including Alpha (B.1.1.7), which first emerged in the United Kingdom and was linked to enhanced transmissibility; Beta (B.1.351) and Gamma (P.1), which originated in South Africa and Brazil, respectively, and exhibited partial resistance to neutralizing antibodies [7]. The Delta variant (B.1.617.2), initially identified in India, caused widespread global outbreaks owing to its high infectivity and potential for increased disease severity [8]. The Omicron variant (B.1.1.529), with its numerous sublineages such as BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, and later XBB and BA.2.86, carried extensive spike mutations that improved immune evasion, while generally leading to less severe disease compared to Delta [9].

COVID-19 was initially classified as a respiratory disease due to its primary symptoms of fever, cough, shortness of breath, and pneumonia, and the high expression of its entry receptor, ACE2, in lung epithelial cells [10]. However, as the pandemic progressed, it became evident that SARS-CoV-2 affects multiple organ systems, including the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and nervous systems, indicating a systemic impact beyond the lungs [11]. Emerging evidence links SARS-CoV-2 to neurodegenerative disorders, as the virus can invade the brain via the olfactory nerve, disrupt the blood–brain barrier, and trigger systemic inflammation. These pathways contribute to prolonged neuroinflammation, elevating cytokines and activating microglia, which may accelerate neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis [12,13]. Studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may promote Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s pathologies through mechanisms such as amyloid-beta aggregation, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, with persistent spike protein in the skull-meninges-brain axis potentially contributing to long-term neurological symptoms [14,15].

The construction and analysis of viral-host protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks have proven to be powerful strategies for understanding how viruses like SARS-CoV-2 interact with human cells [16]. These networks help identify which human proteins the virus targets, giving insight into disrupted cellular pathways and guiding the development of treatments that focus on the host. As new variants of the virus continue to emerge, things get more complicated. Mutations can change how viral proteins interact with human ones, affecting everything from immune response to disease severity [17]. Variants like Alpha, Delta, and Omicron have shown clear differences in how easily they spread, how well they evade immunity, and how severe they are, which makes it important to keep studying how these interactions change over time [18]. This highlights the need for advanced and adaptable PPI network algorithms that can integrate heterogeneous biological datasets and reflect the evolving nature of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Studies using network-based approaches such as those by Gordon et al. (2020) [19] and Stukalov et al. (2021) [20] have demonstrated how viral–host interactome analyses can uncover critical host proteins—such as kinases, ubiquitin ligases, and signaling regulators involved in viral replication and immune dysregulation. Building upon these findings, the development of an improved, efficient, and user-friendly algorithm can enhance the precision of network-based analyses and enable the large-scale identification of biologically relevant alterations in host–pathogen interactions.

In this study, we constructed a comprehensive interaction map between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and their human targets to elucidate how the virus disrupts host cellular processes. To account for the dynamic nature of these interactions, we performed a temporal, variant-specific network analysis to examine how different viral strains modulate host biological pathways. A viral–human protein–protein interaction network was generated from our curated dataset, followed by community detection using the Louvain algorithm. The largest cluster was extracted and visualized through a spring-layout graph. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted using BioEnrichPy, a Python-based tool that integrates seamlessly with the g:Profiler API to provide accurate and consistent identification of affected biological processes and pathways. This customized computational framework enabled the identification of significant shifts in host responses driven by viral mutations. Overall, our findings provide insights into the adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2 across successive waves and reveal variant-specific molecular vulnerabilities that may guide future therapeutic strategies to mitigate the long-term consequences of COVID-19.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted using publicly available data and did not require informed consent or research ethics board approval. The research presented here was performed under the overall research ethics oversight of the authors’ institutions.

2.1. Algorithm Development

We developed BioEnrichPy, a novel Python-based algorithm designed to automate and enhance the enrichment workflow. This tool was specifically developed for identifying enriched biological processes, molecular functions, cellular components, and pathways in the context of human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 proteins. The algorithm aims to improve reproducibility, flexibility, and efficiency, offering a comprehensive and standardized approach to functional annotation. The BioEnrichPy pipeline begins by accepting a curated list of human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 proteins, provided as a spreadsheet (e.g. Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, LibreOffice Calc, Apple Numbers), which is parsed to extract relevant protein identifiers. The algorithm then queries the g: Profiler API to retrieve associated Gene Ontology (GO) terms, including biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), cellular components (CC), and KEGG pathways. Enrichment analysis is performed using a hypergeometric distribution to calculate statistical significance, with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction applied to control for multiple testing, using an FDR threshold of <0.05. The algorithm then filters and prioritizes the top 20 enriched terms, visualizing them through horizontal and circular bar plots generated using Matplotlib (v 3.10.0) and Seaborn (v 0.13.2). The entire process is automated, ensuring efficient, reproducible, and flexible enrichment analysis, with high adaptability to handle large datasets and produce publication-quality graphical outputs.

2.2. Data Collection

To construct a comprehensive SARS-CoV-2-human protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, data were systematically curated from published literature using PubMed’s search engine. The search was performed using the MeSH terms: “SARS-CoV-2” AND “Human” AND “Protein interaction” NOT “Review”. Only studies reporting experimentally validated PPIs were considered for inclusion. The collected interaction data were further categorized based on SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Delta, and Omicron by referencing the year of publication. Since actual viral lineage information was not available in all studies, PPI datasets were categorized by publication year rather than confirmed variant. For a structured organization, the extracted PPIs were tabulated in Excel, with separate sheets assigned to each variant. This structured dataset was then utilized for downstream network analysis.

2.3. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Construction and Visualization

The curated variant-specific PPI datasets were imported into Cytoscape (version 3.10.0) for network visualization and analysis [21]. Separate PPI networks were constructed for each variant to examine their unique and overlapping interactions. In addition to experimentally validated PPIs, we included STRING interactions to expand network coverage.

2.4. Cluster Analysis Using Louvain Community Detection and MCODE

To identify biologically significant subnetworks, cluster analysis was performed using the Louvain community detection algorithm, implemented in Python using the community Louvain package. The algorithm partitions the protein–protein interaction network by maximizing modularity, a measure of the density of connections within communities compared to connections between communities. The process begins by assigning each node to its own community and iteratively merging communities to optimize modularity. After performing the Louvain method on the entire network, the resulting communities were analyzed to extract the largest cluster, which was considered the most prominent sub-network. Additionally, we performed MCODE clustering using the MCODE plugin in Cytoscape to further refine the analysis and identify highly interconnected subnetworks within the network. The resulting clusters were examined to uncover key hub proteins and functional modules associated with each community [22].

2.5. Identification of Highly Connected Proteins

The CytoNCA plugin in Cytoscape was employed to identify highly connected proteins, which are core and regulatory proteins in a biological network [23]. This analysis used the degree parameter (without weight) to examine the network, revealing the top ten hub proteins in the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. The degree of a protein in a given PPI network signifies the number of interactions it shares with other proteins. Proteins with more interactions possess higher degree values in the network.

2.6. Gene Ontology and KEGG-Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Functional enrichment analysis of the human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 proteins was performed using the algorithm BioEnrichPy. This integrative and automated approach allowed for a comprehensive and standardized analysis of the biological pathways and functional categories associated with SARS-CoV-2 human interactome proteins.

3. Results

3.1. Data Evaluation

Our systematic literature search in PubMed using the MeSH terms “SARS-CoV-2” AND “Human” AND “Protein interaction” NOT “Review” yielded 72 relevant articles reporting SARS-CoV-2-human protein–protein interaction. Upon further evaluation, we found that only 18 of these articles contained experimentally validated interaction data. These 18 studies were selected for downstream analysis.

The collected interaction data were categorized based on SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Delta, and Omicron by referencing the year of publication. To ensure a structured dataset, the interactions were tabulated in Excel, with separate sheets assigned to each variant. The curated article information is given in the table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Curated PubMed articles were employed in this study. The variant names are tentative. The most prominent variant of the concerned year has been mentioned.

3.2. Construction of the SARS-CoV-2- Human PPI Network

To construct the SARS-CoV-2-human protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, interaction data obtained from 18 selected studies were imported into Cytoscape (version 3.10.0). The PPI data were categorized based on SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Delta, and Omicron. The interaction data provided by STRING database were further imported into the Cytoscape tool for building and analyzing the network. Separate variant-specific PPI networks were constructed to analyze the differences in host–virus interactions across variants. The variant-specific networks consisted of: Alpha variant: [788] nodes and [1650] edges, Delta variant: [4350] nodes and [12,336] edges and Omicron variant: [5550] nodes and [17,184] edges (Supplementary File S1).

We independently analyzed each variant-specific network using MCODE clustering in Cytoscape to identify highly interconnected subnetworks. This analysis was performed separately for each variant (Supplementary File S2). The resulting clusters were then examined to identify key hub proteins and functional modules associated with each variant. In addition to MCODE clustering, we performed an initial cluster analysis using the Louvain community detection algorithm in Python to partition the protein–protein interaction networks of each SARS-CoV-2 variant by maximizing modularity (Supplementary File S3). A comparative analysis of these networks revealed distinct interaction patterns, showcasing both shared and unique host protein interactions across different variants.

3.3. Hub Protein Identification

To identify highly connected proteins, we used the Cytoscape plug-in CytoNCA to analyze each variant separately. For the Alpha variant (Table 2), key human hub proteins included ACE2 (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2), TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1), SERPING1 (Plasma protease C1 inhibitor), TRAF3 (TNF receptor-associated factor 3), RCHY1 (RING finger and CHY zinc finger domain-containing protein 1), DDP4 (Dipeptidyl peptidase 4), IKBKE (Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase sub-unit epsilon), PRKRA (Interferon-inducible double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase activator A), HNRNPA1 (Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1), EIF3F (Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 sub-unit F) and IRF3 (Interferon regulatory factor 3)with high degree among others.

Table 2.

Hub protein identified for Alpha variant using CytoNCA.

For the Delta variant (Table 3), degree-based ranking identified several highly connected hub proteins, including AP2M1 (adaptor-related protein complex 2 mu 1), G3BP1 (Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1), PEX14 (peroxisomal biogenesis factor 14), ITGB1 (integrin subunit beta 1), ATP1A1 (sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-1), PPP1CA (protein phosphatase 1 catalytic sub-unit alpha), ATP2A2 (sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2), GABARAPL2 (gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein-like 2), G3BP2 (Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 2), PCBP1 (poly(C)-binding protein 1), TERC (transferrin receptor protein 1), ETFA (electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha), NOP58 (nucleolar protein 58), COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), CYP51A1 (lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase), LMAN1 (lectin, mannose-binding 1), SLC3A2 (Amino acid transporter heavy chain SLC3A2), FANCI (Fanconi anemia group I protein), P4HB (Protein disulfide-isomerase) and PTPLAD1 (Very-long-chain (3R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydratase 3), all of which had a degree score above 10.

Table 3.

Hub protein identified for Delta variant using CytoNCA.

Similarly, for the Omicron variant (Table 4), the top hub proteins with a degree score greater than 10 included ATP2A2, SNRPD1 (small nuclear ribonucleoprotein D1), EIF2S1 (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 sub-unit alpha), RPN1 (Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyltransferase subunit 1), STT3A (STT3 oligosaccharyltransferase complex catalytic sub-unit A), SRC (proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src), MBOAT7 (membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 7), DHCR7 (7-dehydrocholesterol reductase), AP2M1, PSMC1 (26S proteasome regulatory sub-unit 4), MCM5 (minichromosome maintenance complex component 5), STT3B (STT3 oligosaccharyltransferase complex catalytic sub-unit B), ADAM9 (ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9), YKT6 (synaptobrevin homolog YKT6), FSCN1 (fascin actin-bundling protein 1), RPL18A (large ribosomal sub-unit protein eL20), RAB14 (Ras-related protein Rab-14), PSMB5 (proteasome sub-unit beta type-5), DDX39B (spliceosome RNA helicase DDX39B), SLC15A (Amino acid transporter), PRMT1 (Protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1), RPN2 (Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2), RPS9 (Small ribosomal sub-unit protein uS4), SUN2 (SUN domain-containing protein 2), ATP5F1B (ATP synthase sub-unit beta, mitochondrial), GANAB (Neutral alpha-glucosidase AB), DHCR7 (7-dehydrocholesterol reductase), RPL18A (Large ribosomal sub-unit protein eL20), RAB14 (Ras-related protein Rab-14), RPS3 (small ribosomal sub-unit protein uS3), RAC1 (Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1), RAB8A (Ras-related protein Rab-8A), ANO6 (Anoctamin-6), RPS7 (Small ribosomal sub-unit protein eS7) and ALDOA (Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A). Among the identified hub proteins, AP2M1, ATP1A1, and ATP2A2 were found to be common interacting nodes shared between the Delta and Omicron variant networks.

Table 4.

Hub protein identified for Omicron variant using CytoNCA.

3.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis

Functional enrichment analysis of host proteins interacting with the Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants revealed key biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions involved in viral pathogenesis and host response.

For the Alpha variant (Supplementary File S4 (Figure S10A–C)), enriched biological processes included viral process and viral gene expression, suggesting active manipulation of host cellular machinery to facilitate viral replication. Additionally, pathways related to protein localization and trafficking, such as protein localization to organelle, establishment of protein localization to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and SRP-dependent translational protein targeting to membrane, were significantly represented, highlighting the critical role of ER-associated translation and trafficking in viral protein synthesis and assembly. Enrichment in RNA metabolism and protein degradation pathways, such as mRNA metabolic process and cellular macromolecule catabolic process, suggests that the virus may influence host mRNA stability and degradation to optimize its replication environment. Key cellular components enriched in the Alpha variant included the ribonucleoprotein complex, ribosome, ribosomal sub-units (both large and small), and cytosolic ribosome, emphasizing the role of host translational machinery in viral replication. Additionally, nuclear outer membrane–ER membrane network and ER sub compartments underscored the significance of the ER in viral protein processing and trafficking. Enrichment in RNA-binding functions, including mRNA binding, mRNA 5′-UTR binding, and single-stranded RNA binding, indicated extensive viral interactions with host mRNA processing and translation regulation. Furthermore, ubiquitin protein ligase binding and ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding suggested a role in modulating host proteostasis and immune evasion.

For the Delta variant (Supplementary File S4 (Figure S11A–C)), biological processes associated with protein localization and intracellular transport were enriched, including protein localization to organelle, cellular macromolecule localization, and intracellular protein transport. The enrichment of viral process and membrane organization suggested active manipulation of host cellular machinery to facilitate viral replication and assembly. Analysis of cellular components revealed enrichment in organelles critical for viral processing and transport, such as the ER membrane, ER sub compartments, Golgi apparatus, and Golgi membrane. Additionally, components like the nuclear outer membrane–ER membrane network, organelle envelope, mitochondrion, and ribonucleoprotein complex were enriched, indicating interactions with multiple organelles involved in viral replication and host cell modulation. Molecular functions related to RNA binding, ATP hydrolysis activity, and nucleoside-triphosphatase activity were identified, supporting energy-dependent viral replication processes. Enrichment in hydrolase activity acting on acid anhydrides and protein-macromolecule adaptor activity pointed to viral exploitation of host enzymatic and protein interaction pathways. Additionally, cell adhesion molecule binding and cadherin binding suggested potential disruptions in host cell adhesion mechanisms, which may facilitate viral entry or spread.

For the Omicron variant (Supplementary File S4 (Figure S12A–C)), enriched biological processes were largely related to protein localization and intracellular transport, including protein localization to organelle, cellular macromolecule localization, and intracellular protein transport. Enrichment in viral process and organonitrogen compound biosynthetic process suggested the virus’s manipulation of host metabolic pathways for efficient replication. Key cellular components enriched in the Omicron variant included the organelle envelope, mitochondrion, ribonucleoprotein complex, and catalytic complex, indicating viral interactions with host cellular machinery involved in replication and protein synthesis. The enrichment of the nuclear protein-containing complex and nuclear outer membrane–ER membrane network further emphasized the involvement of nuclear and ER-associated structures in viral propagation. Enrichment in RNA-binding functions such as mRNA binding, protein-containing complex binding, and protein domain-specific binding suggested interactions with host translation and protein complex formation processes. Furthermore, the identification of nucleoside-triphosphatase activity, adenyl nucleotide binding, pyrophosphatase activity, and hydrolase activity suggested viral exploitation of host metabolic and catalytic pathways. Enrichment of cell adhesion molecule binding and cadherin binding indicated potential disruptions in host cell adhesion, contributing to viral entry and spread.

3.5. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

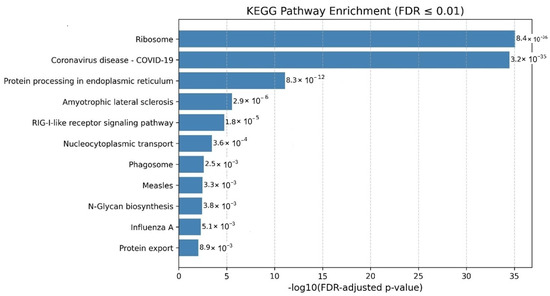

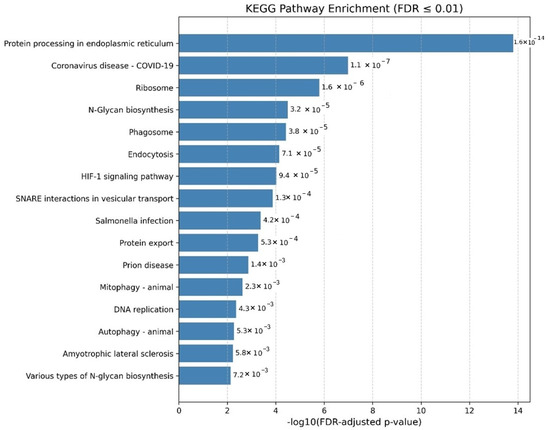

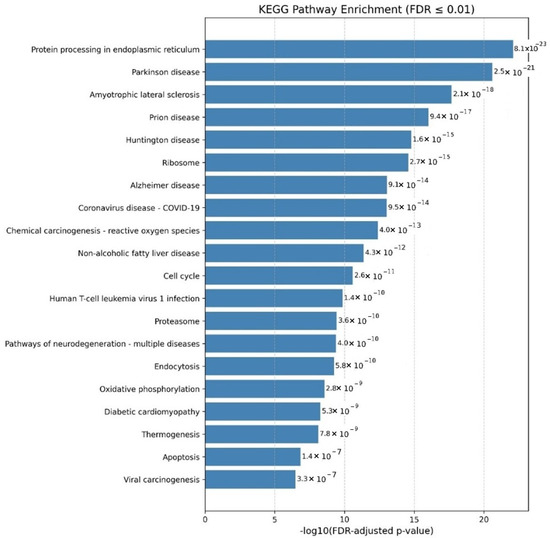

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the Alpha (Figure 1), Delta (Figure 2), and Omicron variants (Figure 3) of SARS-CoV-2 reveals distinct alterations in cellular pathways, reflecting variant-specific impacts on host biological systems. The result shows that each variant differently influences viral pathogenesis, immune responses, and long-term health outcomes.

Figure 1.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant proteins. The most significantly enriched pathways highlighting viral entry and signaling processes targeted by the variant.

Figure 2.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of human proteins interacting with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. Enriched pathways include protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, ribosome, and coronavirus disease pathways, indicating disruptions in host protein folding, translation, and immune signaling associated with increased transmissibility and disease severity.

Figure 3.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of human proteins interacting with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Enriched pathways include those associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, ALS, and prion diseases, suggesting links to neuronal damage and protein aggregation.

The pathway enrichment analysis of the Alpha variant highlights significant alterations in several biological processes related to protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and N-glycan biosynthesis, indicating potential disruptions in protein folding, glycosylation, and processing. These alterations could impair viral replication and the host’s immune response. Enriching the Coronavirus disease pathway further confirms the biological relevance of these host interactions in the context of infection. Additionally, the identification of key pathways such as Ribosome, N-glycan biosynthesis underscores a systematic viral strategy to hijack host translation processes, glycosylation machinery, and intracellular trafficking systems. These mechanisms are likely exploited to enhance viral entry, evade immune detection, and ensure robust viral propagation.

The Delta variant pathway enrichment analysis revealed alterations that may contribute to increased transmissibility and disease severity. Notably, pathways associated with protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum were enriched, indicating potential disruptions in protein folding and quality control mechanisms. These disruptions could impair viral replication and affect the host’s immune response. A significant finding was the enrichment of the Coronavirus disease pathway, reflecting the Delta variant’s direct association with severe disease outcomes. The analysis also revealed enrichment in ribosome-related processes, crucial for protein synthesis, suggesting that the Delta variant may manipulate the host’s translation machinery to facilitate viral replication. Additionally, pathways linked to Salmonella infection, prion disease, and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) suggest overlap with cellular mechanisms involved in immune responses, protein misfolding, and neurodegeneration, which could contribute to the severity and complications associated with the Delta variant. Further, enriched pathways such as endocytosis and N-glycan biosynthesis indicate potential alterations in viral entry, membrane trafficking, and protein glycosylation, influencing viral replication and immune evasion. Additional enrichment in pathways like Autophagy, Prion disease, and Antigen processing and presentation suggests a broader impact on cellular stress responses and immune signaling, potentially contributing to the enhanced transmissibility and pathogenicity associated with the Delta variant.

The pathway enrichment analysis for the Omicron variant revealed a broader and more complex set of alterations, with significant enrichment in pathways related to neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, ALS, prion disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. These findings suggest that Omicron may be linked to processes involved in neuronal damage, protein aggregation, and cognitive decline, highlighting the potential for neurological complications beyond the respiratory effects commonly associated with COVID-19.

Omicron was also associated with cancer-related pathways, including those related to the cell cycle and viral carcinogenesis, suggesting that the variant may influence tumor progression or contribute to the development of cancer. Specifically, pathway-linked Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 (HTLV-1) infections were enriched, indicating a potential role in viral oncogenesis mechanisms. Lastly, including the Coronavirus disease pathway underlines Omicron’s direct association with COVID-19 and its potential to exacerbate disease severity through interactions with host cellular mechanisms.

The Alpha variant primarily affects protein processing and structural cellular functions, which may influence viral replication and immune evasion. The Delta variant is associated with significant alterations in immune response pathways and protein synthesis mechanisms, potentially contributing to the variant’s increased severity and transmissibility. Meanwhile, the Omicron variant exhibited a broader range of effects, influencing neurodegenerative processes, cancer-related pathways, and metabolic disorders, suggesting a more multifaceted impact on human health. It is important to note that KEGG categories related to neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ALS) share substantial gene overlap with ribosomal and proteostasis-associated processes. The observed enrichment likely reflects perturbations in translation and protein-folding machinery, common to viral infection and neuronal stress. Therefore, these results should be interpreted as indicative of disrupted proteostatic balance with potential neurological implications, rather than direct evidence of disease-specific mechanisms.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a novel network analysis tool named BioEnrichPy. Compared to the existing enrichment and network analysis tools, the BioEnrichPy algorithm offers several distinct advantages. Unlike conventional platforms that often require manual intervention and fragmented workflows, BioEnrichPy provides an end-to-end, fully automated solution that integrates network clustering, functional enrichment, and data visualization. Its seamless integration with the g:Profiler API ensures up-to-date and standardized annotation, while customizable parameters allow users to adapt the tool to variant-specific or disease-specific contexts. Additionally, BioEnrichPy’s Python-based framework enhances reproducibility and scalability for high-throughput studies, overcoming the limitations of web-only interfaces or closed-source software. This algorithm’s ability to extract variant-specific pathway enrichment profiles and represent them graphically with publication-ready outputs offers a powerful and efficient alternative to traditional methods. We applied BioEnrichPy to understand the interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and human proteomes over time.

SARS-CoV-2 has undergone significant genetic evolution since its emergence, leading to the development of multiple variants with distinct mutations that influence transmissibility, immune evasion, and disease severity [6]. The major VOCs include Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron along with its numerous sub-lineages. Alpha carried the N501Y mutation, enhancing ACE2 binding and transmissibility, while Beta and Gamma harbored E484K and K417N/T mutations, which contributed to immune escape [24]. Delta, characterized by the L452R and T478K mutations, demonstrated increased infectivity and disease severity. Omicron and its subvariants, with extensive mutations in the spike protein, exhibited heightened immune evasion, allowing reinfections and reduced vaccine effectiveness [6]. The continuous evolution of SARS-CoV-2 underscores the virus’s ability to adapt under selective pressures from host immunity and public health interventions, necessitating ongoing genomic surveillance and adaptive therapeutic strategies [25].

The evolutionary interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and the human immune system exemplifies the Red Queen Hypothesis, which suggests that species must continuously evolve and adapt—not to gain a competitive advantage, but simply to maintain their relative fitness within an ever-changing biological environment [26]. In the context of SARS-CoV-2, this evolutionary arms race is vividly reflected in the virus’s ongoing genetic diversification and the adaptive responses of the human immune system. As the virus circulates within populations, it faces selective pressures that favor mutations enhancing transmissibility, immune evasion, and resistance to neutralizing antibodies—characteristics notably observed in variants such as Delta and Omicron [27]. These adaptive mutations are predominantly concentrated in the spike protein, the principal target of neutralizing antibodies, but also extend to non-structural proteins involved in viral replication, immune modulation, and host cell interactions [28].

In turn, the human host mounts adaptive defenses through natural immunity, booster vaccinations, and the continual development of updated vaccines designed to target emerging variants [26]. Additional protective measures, such as monoclonal antibody therapies and antiviral agents, further strengthen this response. However, these immunological pressures simultaneously drive the virus to evolve, giving rise to new variants capable of evading immune recognition and undermining existing therapeutic strategies. This recurring cycle—where both the virus and host must perpetually adapt to maintain equilibrium—epitomizes the essence of the Red Queen Hypothesis: “it takes all the running you can do to stay in the same place” [27].

Our study offers compelling empirical support for this hypothesis by demonstrating how SARS-CoV-2′s protein–protein interaction with human host proteins evolve over time. Through network-based analyses of variant-specific interactomes for Alpha, Delta, and Omicron, we observed a marked increase not only in the number of host proteins targeted by the virus but also in the diversity of biological pathways disrupted. The Alpha variant predominantly interfered with pathways related to immune modulation and protein translation, consistent with early viral strategies aimed at suppressing immune responses and hijacking host translational machinery. Delta, in contrast, expanded its interaction profile to affect cardiovascular and metabolic systems, correlating with the variant’s increased severity and systemic manifestations. Most notably, the Omicron variant showed enrichment in pathways associated with neurodegeneration, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular stress responses highlighting a potential shift toward long-term host manipulation and the emergence of post-acute COVID-19 syndromes. While the Omicron variant exhibited strong enrichment in pathways associated with neurodegeneration, we recognize that such KEGG categories often co-enrich with ribosomal and proteostasis-related processes. These overlaps may reflect general cellular stress or translational disruption rather than disease-specific neurotoxicity. These progressive and variant-specific adaptations reveal a viral strategy that becomes increasingly complex and system-wide, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 is not just evolving for short-term survival, but for prolonged persistence within host populations. Simultaneously, the human immune system is under pressure to adapt through genomic surveillance, immunogen design, and therapeutic refinement, perpetuating the evolutionary cycle [25,28]. Our findings illustrate that viral evolution is not random but shaped by specific functional pressures imposed by host immunity and medical interventions.

Several studies have identified the protein–protein interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and human host proteins to understand viral pathogenesis and identify potential therapeutic targets. One of the earliest large-scale studies identified 332 high-confidence SARS–CoV–2–human PPIs, revealing key host pathways involved in viral replication, ubiquitination, and innate immune signaling [27]. Further, a comprehensive interactome analysis using affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) and proximity-labeling methods highlighted the virus’s ability to manipulate autophagy, nuclear transport, and immune evasion pathways [29]. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening approaches identified interactions with host transcription factors, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 modulates gene expression and inflammatory responses during infection [30]. Another study investigates the mechanism underlying lung macrophage hyperactivation in severe COVID-19. While macrophages contribute to the cytokine storm, they are largely not infected by SARS-CoV-2, leaving their activation pathway unclear. The researchers identified plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) as a key source of type I interferons (IFN-I) in the lungs of infected patients. pDC infiltration correlated with strong IFN-I signaling in macrophages, and persistent IFN-I signaling was associated with an inflammatory macrophage signature in severe cases. They found that pDCs primarily produced IFN-α in response to SARS-CoV-2, while macrophages required physical contact with infected epithelial cells to do so. IFN-α from pDCs, via TLR7 sensing, induced transcriptional and epigenetic changes in macrophages, priming them for hyperactivation by environmental stimuli. This study highlights the role of pDC-driven IFN-I responses in shaping macrophage activation, contributing to the severe inflammatory response in COVID-19 [31,32]. Studies on SARS-CoV-2-human protein–protein interaction have treated mainly the virus as a single entity, overlooking the distinct molecular interactions exhibited by different variants.

Our study addresses this gap by systematically analyzing the host-PPI networks of Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants, revealing unique interaction patterns that may explain their differing transmissibility, immune evasion, and pathogenic potential. The increasing complexity of PPI networks from Alpha to Omicron shows an evolutionary shift in viral strategies to exploit host cellular mechanisms more efficiently. Omicron exhibits enrichment in pathways associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS, raising concerns about its long-term neurological impact. This aligns with emerging clinical evidence of persistent neurological symptoms in post-acute COVID-19 cases, potentially driven by neuroinflammation, blood–brain barrier disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation, all implicated in neurodegenerative pathophysiology. Several recent studies have demonstrated the association of omicron variant with a variety of neurological manifestations [31,32,33,34].

We independently performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using ShinyGO and compared these results with those obtained from BioEnrichPy; the comparative data are provided in Supplementary File S5, supporting the reliability and analytical value of BioEnrichPy. Additionally, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of hub proteins revealed variant-specific disruptions (Supplementary Files S6 and S7). For the Alpha variant, enriched pathways are primarily associated with immune activation, including RIG-I-like receptor, Toll-like receptor, and renin-angiotensin signaling, as well as viral infection pathways such as Hepatitis B, Epstein–Barr virus, and Influenza A, suggesting potential virus–host interactions. In the Delta variant, enrichment of cardiomyopathy-related pathways (e.g., hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy) and cAMP/cGMP-PKG signaling indicates possible cardiovascular dysfunction and vascular disturbances. In contrast, the Omicron variant exhibits pronounced enrichment in neurodegenerative pathways, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and prion diseases, alongside HIF-1 and AMPK signaling, reflecting metabolic stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired protein homeostasis. These findings show Alpha is linked to immune response, Delta to cardiovascular dysfunction, and Omicron to neurodegeneration.

5. Conclusions

Our study presents a variant-specific analysis of SARS-CoV-2–host interactions using a novel custom-made interactomics algorithm: BioEnrichPy. By comparing Alpha, Delta, and Omicron PPI networks, we revealed how viral evolution progressively enhances host pathway disruption, with Omicron notably linked to neurodegenerative processes. It should be noted, however, that PPI datasets were categorized into Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants solely based on publication year, which may not fully account for the co-circulation of multiple variants during the same time periods. BioEnrichPy enabled efficient, automated enrichment analysis, outperforming conventional tools in adaptability and scalability. Our results support the Red Queen Hypothesis, highlighting continuous coevolution between the virus and host immune responses. These findings emphasize the importance of genomic surveillance, flexible computational tools, and targeted strategies to mitigate the long-term effects of emerging variants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid5120203/s1.

Author Contributions

R.D. designed the study. S.K., A.A.I., P.S., H.N. and S.S. performed the experiments. Data analyzed by S.K., S.S. and H.N. R.D. supervised the analysis. Manuscript written by S.K. and edited by R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding for this project. The article processing charges will be partially supported by Yenepoya (Deemed to be University).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was conducted using publicly available data and did not require informed consent or research ethics board approval.

Informed Consent Statement

The present study was conducted using publicly available data and did not require informed consent or research ethics board approval.

Data Availability Statement

We employed publicly available datasets. These can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| TMPRSS2 | Transmembrane Protease, Serine 2 |

| VOC | Variant of Concern |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| BP | Biological Process |

| MF | Molecular Function |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| AP-MS | Affinity Purification–Mass Spectrometry |

| Y2H | Yeast Two-Hybrid |

| pDC | Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell |

| IFN-I | Type I Interferon |

| IFN-α | Interferon Alpha |

| TLR7 | Toll-Like Receptor 7 |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| HTLV-1 | Human T-cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 |

References

- Lai, C.C.; Shih, T.P.; Ko, W.C.; Tang, H.J.; Hsueh, P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.A.; Rojas-Valencia, N.; Gómez, S.; Egidi, F.; Cappelli, C.; Restrepo, A. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 to Cell Receptors: A Tale of Molecular Evolution. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Mao, Y.; Jones, R.M.; Tan, Q.; Ji, J.S.; Li, N.; Shen, J.; Lv, Y.; Pan, L.; Ding, P.; et al. Aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2? Evidence, prevention and control. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Spike protein mediated membrane fusion during SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabidi, N.Z.; Liew, H.L.; Farouk, I.A.; Puniyamurti, A.; Yip, A.J.; Wijesinghe, V.N.; Low, Z.Y.; Tang, J.W.; Chow, V.T.; Lal, S.K. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants: Implications on immune escape, vaccination, therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Viruses 2023, 15, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Fawaz, M.A.; Aisha, A. A comparative overview of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants of concern. Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan, M.; Sharma, A.; Priyanka, N.; Thakur, N.; Rajkhowa, T.K.; Choudhary, O.P. Delta variant (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2: Mutations, impact, challenges and possible solutions. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2068883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, D.; Staropoli, I.; Michel, V.; Lemoine, F.; Donati, F.; Prot, M.; Porrot, F.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Jeyarajah, B.; Brisebarre, A.; et al. Distinct evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB and BA. 2.86/JN. 1 lineages combining increased fitness and antibody evasion. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, B.; Vesal, A.; Edalatifard, M. Coronavirus and Its effect on the respiratory system: Is there any association between pneumonia and immune cells. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4729–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopańska, M.; Barnaś, E.; Błajda, J.; Kuduk, B.; Łagowska, A.; Banaś-Ząbczyk, A. Effects of SARS-CoV-2 inflammation on selected organ systems of the human body. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedran, D.; Bedran, G.; Kote, S. A comprehensive review of neurodegenerative manifestations of SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines 2024, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Y. Potential mechanism of SARS-CoV-2-associated central and peripheral nervous system impairment. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 146, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiken, S.; Sittenfeld, L.; Dridi, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Marks, A.R. Alzheimer’s-like signaling in brains of COVID-19 patients. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Mai, H.; Ebert, G.; Kapoor, S.; Puelles, V.G.; Czogalla, J.; Hu, S.; Su, J.; Prtvar, D.; Singh, I.; et al. Persistence of spike protein at the skull-meninges-brain axis may contribute to the neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 2112–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, W.; Li, D.; Pan, T.; Guo, J.; Zou, H.; Tian, Z.; Li, K.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; et al. Comprehensive characterization of human–virus protein-protein interactions reveals disease comorbidities and potential antiviral drugs. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, P.; Niyogi, S. SARS-CoV-2 mutations: The biological trackway towards viral fitness. Epidemiol. Infection. 2021, 149, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Madabhavi, I. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: A review. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2023, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukalov, A.; Girault, V.; Grass, V.; Karayel, O.; Bergant, V.; Urban, C.; Haas, D.A.; Huang, Y.; Oubraham, L.; Wang, A.; et al. Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Nature 2021, 594, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.D.; Hogue, C.W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Wu, F.X. CytoNCA: A cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Biosystems 2015, 127, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S. E484K and N501Y SARS-CoV 2 spike mutants Increase ACE2 recognition but reduce affinity for neutralizing antibody. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 102, 108424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Redondo, R.; de Sant’Anna Carvalho, A.M.; Hultquist, J.F.; Ozer, E.A. SARS-CoV-2 genomics and impact on clinical care for COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78 (Suppl. S2), ii25–ii36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzine, I.M.; Rozhnova, G. Evolutionary implications of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for the future design of vaccination strategies. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Xia, N.; Yuan, Q. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants: Genetic impact on viral fitness. Viruses 2024, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya, R.; Swaminathan, A.; Shamim, U.; Arora, S.; Mishra, P.; Raina, A.; Ravi, V.; Tarai, B.; Budhiraja, S.; Pandey, R. Co-evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants and host immune response trajectories underlie COVID-19 pandemic to epidemic transition. Iscience 2023, 26, 108336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Edwards, R.J.; Manne, K.; Martinez, D.R.; Schäfer, A.; Alam, S.M.; Wiehe, K.; Lu, X.; Parks, R.; Sutherland, L.L.; et al. In vitro and in vivo functions of SARS-CoV-2 infection-enhancing and neutralizing antibodies. Cell 2021, 184, 4203–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P.; Yang, C.; Rendeiro, A.F.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Carrau, L.; Chandar, V.; Bram, Y.; tenOever, B.R.; Elemento, O.; Ivashkiv, L.B.; et al. Sensing of SARS-CoV-2 by pDCs and their subsequent production of IFN-I contribute to macrophage-induced cytokine storm during COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eadd4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachman-Kapułka, J.; Zińczuk, A.; Simon, K.; Rorat, M. Cross-section of neurological manifestations among SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants: Single-center study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, P.; Qi, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Yan, B.; et al. Neurological complications during the Omicron COVID-19 wave in China: A cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, A.; Kim, H.; Chae, J.H.; Kim, K.J.; Park, D.; Kwon, Y.S.; Kim, M.J.; et al. Severe neurological manifestation associated with coronavirus disease 2019 in children during the Omicron variant-predominant period. Pediatr. Neurol. 2024, 156, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Wang, P.; Shen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, L.; Nie, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, W. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with mild to moderate infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Shanghai, China. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).