Abstract

Saliva specimens are widely used for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) testing using RT-qPCR due to their advantages over nasopharyngeal swabs of being non-invasive and self-collectable. However, saliva collection can be time-consuming in individuals with reduced saliva secretion, including those with diabetes, diseases involving salivary glands such as Sjögren’s syndrome, and older adults. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of mouth rinse specimens, which can be easily collected even from individuals with reduced saliva secretion, as an alternative to saliva for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing. Among the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) positive specimens analyzed, 88.2% were derived from patients possessing risk factors associated with reduced salivary secretion, including diabetes, use of medications such as anticholinergics or antihistamines, smoking, and older age. The analysis results of mouth rinse specimens demonstrated 96.7% overall agreement with those of saliva specimens, with a sensitivity of 94.1% and specificity of 100%; however, the viral load in the mouth rinse specimens was lower than that in saliva because of sample dilution. These findings suggest that mouth rinse specimens are a practical, versatile, and reliable alternative specimen for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is characterized by fever, dry cough, and other serious complications [1,2,3]. COVID-19 remains a public health concern due to the ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 strains [4,5]. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the development of accurate and rapid diagnostic tests has become essential [6]. Currently, numerous tests for COVID-19 are available, including nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) and antigen tests. Among these, RT-qPCR, categorized as an NAAT, is the most widely used method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 and is considered the gold standard method by the World Health Organization (WHO) [6]. Nasopharyngeal swabs are the common sampling method for RT-qPCR testing. However, appropriate collection often requires trained healthcare professionals [7]. Therefore, self-collected saliva specimens have been used as an alternative. Saliva collection offers advantages such as convenience, noninvasiveness, and reduced resource consumption. Nevertheless, saliva collection can be time-consuming for individuals with reduced salivary secretion, such as older individuals and patients with diabetes or diseases involving salivary glands, such as Sjögren’s syndrome. In the present study, we evaluated whether mouth rinse specimens could serve as an alternative to saliva for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing. This study proposes a versatile specimen collection method that enables the sampling of a broader range of individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM), Japan (NCGM-G-004065-00).

2.2. Study Subjects and Specimen Collection

We conducted a prospective observational study of patients with COVID-19 and those without COVID-19 (control group) admitted to NCGM between June 2021 and September 2023. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected on admission and tested for SARS-CoV-2 to confirm infection. Patients aged < 20 years and those with insufficient specimens for the study were excluded. Overall, 19 patients were enrolled in the study, 10 of whom were positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 9 were negative. After obtaining informed consent from all participants, saliva was collected, followed by mouth rinse specimens. Participants were instructed to swish 2 mL of water (commercially available natural mineral water) in their mouths for a few seconds without gargling and then spit the solution into the collection tube. They were also instructed to refrain from eating, drinking, brushing their teeth, or gargling for 10–30 min before sample collection. Paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens were collected twice at different times from 11 patients enrolled in 2023 (7 patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 4 patients who were negative for SARS-CoV-2), and once from the other patients enrolled in 2021–2022, resulting in a combined total of 30 paired specimens. All specimens were collected in sterile tubes, frozen at −80 °C as soon as possible, and preserved until subsequent use.

2.3. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

The specimens were diluted two-fold with DPBS(–), mixed vigorously, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and 200 µL of the supernatant was used for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using the MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or the MagMAX Prime Viral/Pathogen NA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed in duplicate using the Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System III (Cy5) (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) with the SARS-CoV-2 direct detection RT-qPCR kit (RD001/RD003; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. This RT-qPCR kit detects SARS-CoV-2 RNA (N gene) using Cy5 and the human RNaseP gene RNA as an internal control using FAM to verify sample quality. Two reagent lots (AO2B005 and AO5B001) with no detectable lot-to-lot variation were used. Positive controls, consisting of SARS-CoV-2 synthetic RNA (SARS-CoV-2 Positive Control [RNA]; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), and negative controls (RNase-free water; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) were included in each run to validate the RT-qPCR assay. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 was determined based on the cycle threshold (Ct) values, with specimens considered positive if an increasing amplification curve was observed within 45 cycles in one or both wells, provided that no amplification was detected in the negative controls.

2.4. Statistics

Overall agreement, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were obtained using epi.tests function of the epiR package (version 2.0.78) in R 4.3.1, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated by the Wilson method (epiR: Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epiR. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to compare the Ct values between saliva and mouth rinse specimens. Statistical significance was defined as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.0; Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

We evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of saliva and mouth rinse specimens for the diagnosis of COVID-19. A total of 30 paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens were collected from 10 patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive and 9 patients who were SARS-CoV-2 negative for this experiment. The positive and negative results obtained from saliva specimens were in complete agreement with those obtained from the nasopharyngeal swabs collected on the same day (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1). We found the overall agreement between saliva and mouth rinse specimens to be 96.7% (95% CI: 83.3–99.4%), with a sensitivity of 94.1% (95% CI: 73.0–99.0%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI: 77.2–100%) (Table 1). Among the 17 paired specimens from patients with positive viral detection, saliva and mouth rinse specimens were both positive in 16 cases (94.1%), while 1 case (5.9%) had saliva-positive/mouth rinse-negative results. A pairwise comparison of Ct values between saliva and mouth rinse specimens was performed using a Bland–Altman Plot, demonstrating a high agreement between the two specimen types (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1.

Comparison of qualitative results of COVID-19 testing using saliva and mouth rinse specimens.

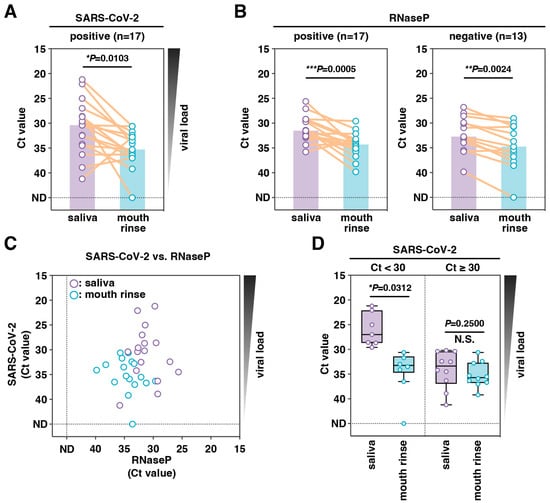

We next examined the Ct value differences in SARS-CoV-2 and RNaseP (a human internal control gene) between saliva and mouth rinse specimens. Among the 17 paired specimens from patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive, the Ct values for SARS-CoV-2 of mouth rinse specimens were significantly higher than those of saliva (median Ct values, 35.3 vs. 30.4, p = 0.0103) (Figure 1A). The SARS-CoV-2 RNA copy number in mouth rinse specimens was also significantly lower than that in saliva (median, 6.8 copies/µL vs. 178.4 copies/µL, p = 0.0009) (Supplementary Figure S2). Similarly, the Ct values for RNaseP of mouth rinse specimens were significantly higher than those of saliva, regardless of whether the SARS-CoV-2 test results were positive or negative (positive: median Ct values, 34.3 vs. 31.5, p = 0.0005; negative: median Ct values, 34.8 vs. 32.8, p = 0.0024) (Figure 1B). The Ct values for both SARS-CoV-2 and RNaseP tended to be lower in saliva and higher in mouth rinse specimens (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Comparison of sensitivities for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection between paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens. SARS-CoV-2 (A) and RNaseP (as an internal control) (B) were detected using RT-qPCR analysis of paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens. Purple and blue bars show the median Ct values of the saliva and mouth rinse specimens, respectively. (C) Correlations between the Ct values of SARS-CoV-2 and RNaseP. (D) Comparison of Ct values between paired specimens with different saliva Ct values (low: <30, high: ≥30). The centerline of the box plot represents the median Ct value, the box represents the interquartile range, and the whiskers display the minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test (N.S.: not significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Analysis of the differences in Ct values for SARS-CoV-2 in the low Ct (saliva Ct < 30) and high Ct (saliva Ct ≥ 30) groups revealed that the median difference was only significant when the saliva had a lower Ct value, representing higher viral loads (Figure 1D). The median differences were 6.25 in the lower and 2.35 in the higher Ct group. The effect of a lower viral load was marginal, as the sensitivity of mouth rinse specimens for diagnosing COVID-19 was high (Table 1).

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the utility of self-collected mouth rinse specimens as an alternative to saliva for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing. Although mouth rinse specimens contained lower viral loads than saliva specimens due to sample dilution, the total agreement in detection ability was 96.7%, with a sensitivity of 94.1% and a specificity of 100% (Table 1). Previous studies have compared the detection sensitivity of saliva and gargle specimens and examined various factors influencing mouth rinse specimen collection. Regarding mouth rinse solutions, studies using saline and water gargle samples reported overall sensitivities of 97% and 86%, respectively, and broadly similar overall specificity (96% vs. 100%) [8]. Regarding the volume of mouth rinse solution, studies using ≤5 mL of mouth rinse solution reported higher overall sensitivity (92% vs. 87%) and specificity (99% vs. 93%) compared with those using >5 mL of mouth rinse solution [8]. Gargle specimens have been reported to have lower sensitivity than saliva [9,10,11]. This is mainly because mouth rinse specimens are diluted in the solution. A smaller volume (1–2 mL) of mouth rinse solution may be used to limit the dilution of the viral concentration in the gargle [7]. Regarding the duration of gargling, studies requiring a total gargling time of >10 s reported a higher overall sensitivity (95% vs. 86%) and specificity (100% vs. 89%) compared to those requiring ≤10 s of gargling [8]. Overall, using saline and having a mouth rinse solution volume of 1–2 mL and a time of >10 s are recommended for the collection of mouth rinse specimens. Based on these reports, the volume of mouth rinse solution used in our study was considered appropriate. Additionally, using saline and rinsing for >10 s may result in a higher concordance rate. In this study, the immediate collection of mouth rinse specimens following saliva sampling may have reduced the oral saliva volume, potentially leading to a lower viral load in the mouth rinse specimens. Consequently, higher viral loads may be observed when mouth rinse specimens are collected independently. Importantly, despite dilution with rinsing water and sequential collection following saliva sampling, mouth rinse specimens retained high sensitivity, indicating their potential applicability under low viral load conditions. Several studies have reported that self-collected gargle specimens exhibit sensitivity comparable to saliva [12,13]. Although our study had the limitation of a small number of specimens, the results were consistent with those of previous studies.

Previous studies comparing viral loads between nasopharyngeal swabs and gargle specimens have demonstrated that the difference in viral load tends to be greater in individuals with high nasopharyngeal viral loads [12,14,15,16]. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding has been reported to persist longer in saliva than in nasopharyngeal swabs, likely due to a more rapid decline in viral load within the nasopharynx [12,17,18,19]. In the present study, we compared viral loads between saliva and mouth rinse specimens (Figure 1A) and found that the difference in viral load was greater when the viral load in saliva was high, and smaller when the viral load was low (Figure 1D). This trend parallels the findings from previous comparisons between nasopharyngeal swabs and gargle specimens [12,14,15,16]. This result implies that saliva specimens may contain secretions not only from the oral cavity but also, to a minor extent, from the pharynx. In contrast, short-duration mouth rinse specimens are presumed to more specifically reflect constituents derived from the oral cavity. However, the present study is limited by a small sample size, and further large-scale studies are needed for a more comprehensive evaluation.

Mouth rinse specimens can be self-collected by patients; therefore, the need for healthcare workers and personal protective equipment (PPE) to conduct the sampling is reduced, thereby improving testing efficiency. In addition, mouth rinsing offers several practical advantages for sample collection. First, it is less likely to generate aerosols or droplets, which enhances safety and makes it particularly suitable for drive-through testing. Second, unlike gargling, mouth rinsing can be easily performed by children and older adults, indicating its potential utility in pediatric or geriatric care facilities. Furthermore, using water as a mouth rinsing solution provides advantages in terms of cost and availability, particularly in clinical settings. Collectively, these features suggest that mouth rinse specimens could serve as a convenient and safe alternative for large-scale SARS-CoV-2 testing. Patients with COVID-19 frequently exhibit xerostomia, which might reduce saliva volume and increase viscosity, hampering sample collection and lowering test sensitivity [20]. Mouth rinse specimens are expected to alleviate these issues, particularly in patients with reduced saliva production, such as those with diabetes, salivary gland disorders (e.g., Sjögren’s syndrome), those taking medications including anticholinergics or antihistamines, or in older adults. Indeed, in this study, 88.2% (15/17) of the specimens were obtained from patients at risk of reduced salivary secretion (Supplementary Table S2); however, a high concordance rate was observed between saliva and mouth rinse specimens.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small, resulting in limited statistical power and a bias toward specimens obtained from a single institution in Japan; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Second, the sensitivity of the mouth rinse specimens may have been underestimated, as they were collected immediately after saliva collection and water, rather than saline, was used.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that self-collected mouth rinse specimens could serve as a practical and effective alternative to saliva for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing and are expected to reduce the burden on both healthcare workers and patients during specimen collection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid5120202/s1, Figure S1: Correlation and agreement between specimens for RT-qPCR COVID-19 testing; Figure S2: Comparison of sensitivities for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection between paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens; Table S1: Comparison of qualitative results of COVID-19 testing using saliva and nasopharyngeal swab specimens; Table S2: Clinical characteristics of participants and their paired saliva and mouth rinse specimens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T.-H. and M.K.; investigation, K.F. and A.K.; resources, J.S.T., A.K. and J.T.-H.; analysis, all the authors; writing—original draft preparation, K.F. and M.K.; project administration, W.S., J.T.-H. and M.K.; funding acquisition, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Nippon Genetics Co., Ltd. (20C031).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM), Japan (NCGM-G-004065-00), 11 September 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the members of the Department of Academic-Industrial Partnerships Promotion and the Department of Clinical Research Promotion, Center for Clinical Sciences, Japan Institute for Health Security, for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

W.S. received research grants from Nippon Genetics Co., Ltd. (20C031). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| NAATs | Nucleic acid amplification tests |

| DPBS(–) | Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| RNaseP | Ribonuclease P |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C. The Emergence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2024, 11, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roederer, A.L.; Cao, Y.; St Denis, K.; Sheehan, M.L.; Li, C.J.; Lam, E.C.; Gregory, D.J.; Poznansky, M.C.; Iafrate, A.J.; Canaday, D.H.; et al. Ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 drives escape from mRNA vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, R.; Carvalho, V.; Faria, B.; Miranda, I.; Catarino, S.; Teixeira, S.; Lima, R.; Minas, G.; Ribeiro, J. Diagnosis Methods for COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kumblathan, T.; Tao, J.; Xu, J.; Feng, W.; Xiao, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, C.V.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Recent advances in RNA sample preparation techniques for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva and gargle. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, N.N.Y.; So, H.C.; Cowling, B.J.; Leung, G.M.; Ip, D.K.M. Performance of saline and water gargling for SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase PCR testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poukka, E.; Makela, H.; Hagberg, L.; Vo, T.; Nohynek, H.; Ikonen, N.; Liitsola, K.; Helve, O.; Savolainen-Kopra, C.; Dub, T. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Gargle, Spit, and Sputum Specimens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0003521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, M.; Agullo, V.; de la Rica, A.; Infante, A.; Carvajal, M.; Garcia, J.A.; Gonzalo-Jimenez, N.; Cuartero, C.; Ruiz-Garcia, M.; de Gregorio, C.; et al. Performance of Saliva Specimens for the Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the Community Setting: Does Sample Collection Method Matter? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e03033-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohmer, N.; Eckermann, L.; Boddinghaus, B.; Gotsch, U.; Berger, A.; Herrmann, E.; Kortenbusch, M.; Tinnemann, P.; Gottschalk, R.; Hoehl, S.; et al. Self-Collected Samples to Detect SARS-CoV-2: Direct Comparison of Saliva, Tongue Swab, Nasal Swab, Chewed Cotton Pads and Gargle Lavage. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, R.; Hapsari, R.; Puspitasari, I.; Sari, D.; Hendrianingtyas, M.; Nurainy, N. Self-collected gargle specimen as a patient-friendly sample collection method for COVID-19 diagnosis in a population context. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, D.M.; Tilley, P.; Al-Rawahi, G.N.; Srigley, J.A.; Ford, G.; Pedersen, H.; Pabbi, A.; Hannam-Clark, S.; Charles, M.; Dittrick, M.; et al. Self-Collected Saline Gargle Samples as an Alternative to Health Care Worker-Collected Nasopharyngeal Swabs for COVID-19 Diagnosis in Outpatients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e02427-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumaresq, J.; Coutlee, F.; Dufresne, P.J.; Longtin, J.; Fafard, J.; Bestman-Smith, J.; Bergevin, M.; Vallieres, E.; Desforges, M.; Labbe, A.C. Natural spring water gargle and direct RT-PCR for the diagnosis of COVID-19 (COVID-SPRING study). J. Clin. Virol. 2021, 144, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, J.; Scholtes, S.; Ottinger, M.; Kremer, M.; Kharazi, A.; Stadler, V.; Bickmann, J.; Zeleny, C.; Kuiper, J.W.P.; Hauck, C.R. Self-Collected Gargle Lavage Allows Reliable Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in an Outpatient Setting. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0036121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Tan, T.; Chen, L.; Bao, J.; Han, D.; Yu, F. Clinical Performance of Self-Collected Purified Water Gargle for Detection of Influenza a Virus Infection by Real-Time RT-PCR. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, M.; Proudfoot, K.; Mathys, V.; Yu, S.; Krieger, N.; Gernon, T.; Gokli, K.; Hamilton, S.; Cook, C.; Fong, Y. A review of nasopharyngeal swab and saliva tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection: Disease timelines, relative sensitivities, and test optimization. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyene, G.T.; Alemu, F.; Kebede, E.S.; Alemayehu, D.H.; Seyoum, T.; Tefera, D.A.; Assefa, G.; Tesfaye, A.; Habte, A.; Bedada, G.; et al. Saliva is superior over nasopharyngeal swab for detecting SARS-CoV2 in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopoorian, A.; Banada, P.; Reiss, R.; Elson, D.; Desind, S.; Park, C.; Banik, S.; Hennig, E.; Wats, A.; Togba, A.; et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva: Implications for late-stage diagnosis and infectious duration. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H. Characterization and Pathogenic Speculation of Xerostomia Associated with COVID-19: A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).