Abstract

Background: This study aimed to assess whether methylprednisolone treatment, while effective in reducing COVID-19 mortality, increases the risk of intensive-care-unit-acquired respiratory tract infections (RTI-ICU) in critically ill patients. Methods: This was a multicenter prospective cohort study conducted in ten countries across Latin America and Europe. It included patients over 18 years of age with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who required ICU admission. A multivariable logistic regression analysis and propensity score matching (PSM) were performed to determine the association between methylprednisolone treatment and RTI-ICU. Results: A total of 3239 patients were included, of whom 1527 patients (47.1%) were treated with methylprednisolone. Methylprednisolone treatment was associated with a higher risk of developing RTI-ICU (OR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.33–1.91). Patients with RTI-ICU had a significantly higher average number of days on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) (24.6, SD: 15.9 vs. 9.5, SD: 11.7; p < 0.001), longer hospital stays (40 days, SD: 24.9 vs. 24.4 days, SD: 18.7; p < 0.001), and higher ICU mortality (39.2%, 259/660 vs. 29.2%, 754/2579; p < 0.001). Conclusions: Methylprednisolone treatment is associated with an increased risk of RTI-ICU in critically ill patients with COVID-19. RTI-ICU was linked to higher mortality, a greater need for invasive mechanical ventilation, prolonged ICU stay, elevated leukocyte and C-reactive protein levels, and a higher comorbidity burden. However, methylprednisolone may not be the sole factor explaining these differences, as residual confounding related to baseline disease severity and comorbidities could have influenced the outcomes.

1. Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), triggered a global health emergency that has resulted in millions of deaths and a profound impact on healthcare systems worldwide [1,2]. Severe forms of COVID-19 are characterized by a dysregulated host immune response and a hyperinflammatory state that can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, and multiorgan failure, frequently requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [3,4].

Systemic corticosteroids have become a cornerstone in the treatment of severe COVID-19 after evidence demonstrated their ability to reduce mortality and the need for organ support in critically ill patients [5,6,7,8]. However, most of the available data are centered on dexamethasone, and the safety profile of other corticosteroids, particularly methylprednisolone, remains less well defined. Methylprednisolone has been extensively used due to its high pulmonary penetration and potent anti-inflammatory properties, yet there is growing concern that it may also increase susceptibility to ICU-acquired infections [8,9,10,11].

There is currently insufficient evidence comparing the infection risk associated with methylprednisolone versus other corticosteroids in real-world critical care settings, representing an important gap in the literature [12,13,14,15]. Therefore, we conducted this multicenter study to evaluate the association between methylprednisolone use and the development of respiratory tract infections acquired in the intensive care unit (RTI-ICU) in critically ill COVID-19 patients, and to assess their impact on clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A multicenter prospective cohort study was conducted in 84 ICUs across ten countries, covering the period from March 2020 to January 2021, with subjects admitted due to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. These ICUs, located in Latin American countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Argentina and European countries such as Spain and Italy allowed for the representation of a wide geographical and clinical diversity. Patients were included in a voluntary prospective registry created by the Latin American Intensive Care Network (Red LIVEN—https://www.redliven.org/web/; accessed on 1 January 2023) and the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SEMICYUC) (NCT04948242) [16,17].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Patients over 18 years of age hospitalized in the ICU for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection were included. A modified severity criterion from the World Health Organization was used to identify patients with severe and critical SARS-CoV-2 disease, defined as individuals with peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) < 94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of partial oxygen pressure to inspired oxygen fraction (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 mmHg, respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, >50% pulmonary infiltrates, or individuals with respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction [17]. Exclusion criteria included patients who received dexamethasone outside the specified timeframe (24 h from admission) and those who received corticosteroids other than methylprednisolone. Additionally, the presence of relevant comorbidities and preexisting conditions that could influence the treatment response was considered. The treating physician determined the dose and duration of methylprednisolone, adjusting it based on the individual clinical response. Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) on a respiratory sample in each hospital according to local protocols [17,18].

2.3. Clinical Variables

The evaluated variables were divided into two main groups: first, demographic data, comorbidities, and initial symptoms and second, physiological variables collected during the first 24 h of ICU admission, along with systemic complications and treatments used during hospitalization. The treating physicians collected data through medical record reviews and laboratory data. Two groups were identified: one that received corticosteroid treatment solely with methylprednisolone within the first 24 h of hospital admission, and another that did not receive corticosteroid treatment.

RTI-ICU was defined as a clinical syndrome of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis (VAT), or hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) [19]. VAP is described as pneumonia that develops more than 48 h after endotracheal intubation. VAT is characterized by fever without an identifiable cause, new or increased sputum production, a positive culture of endotracheal aspirate (>106 CFU/mL) revealing a new bacterium, and the absence of radiographic evidence of nosocomial pneumonia [19]. HAP is defined as pneumonia occurring 48 h or more after ICU admission in patients without invasive mechanical ventilation, if it was not in incubation at the time of admission. Additionally, only cases with isolation of respiratory pathogens in samples such as tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage, sputum, or pleural fluid collected after the first 48 h of ICU admission were considered as ICU-acquired respiratory infections.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Patients were selected through simple random sampling from the list of patients treated during the study period. Quantitative variables were summarized using measures of central tendency and dispersion; means and standard deviations (SD) for normal distributions, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normal distributions. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, considering a p-value < 0.05 as significant. Qualitative variables were presented in frequencies and percentages. For comparison of quantitative variables, Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was applied, depending on the data distribution. For qualitative variables, the Chi-square test was used.

Two multivariate logistic regression models were developed to evaluate the relationship between methylprednisolone use and RTI-ICU in patients with severe COVID-19, as well as the factors associated with the administration of this treatment (dependent variables). Explanatory variables included demographic data, comorbidities, physiological variables collected during the first 24 h of ICU admission, days of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), days in ICU, and duration of hospital stay. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the initial bivariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model. Model quality was assessed by the area under the curve (AUC), and goodness-of-fit was determined using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test [20].

A propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed to mitigate selection bias related to differences in baseline characteristics and disease severity between individuals treated or not with methylprednisolone during the first 24 h of admission. Characteristics included in the matching model were: sex, age, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic lung disease, asthma, chronic kidney disease, neurological disease, hematologic disease, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), obesity, diabetes, rheumatologic disease, use of IMV, IMV duration, ICU stay, hospitalization duration, leukocyte count, creatinine levels, C-reactive protein, oxygen partial pressure (PaO2), inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2), tocilizumab administration, and admission country.

Balance between treated and untreated groups was evaluated using standardized mean differences. Subsequently, a PSM was estimated using a logistic regression model, and a comparison between groups was performed using nearest neighbor matching (NNM). Pre- and post-matching balance was compared using standardized mean differences and the Rubin index, ensuring adequate comparability between treated and untreated groups. After matching, the average treatment effect (ATE) and the average treatment effect for the treated (ATET) were calculated, along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Additionally, to explore potential confounding factors related to the development of ICU-acquired respiratory infections associated with tocilizumab administration in subjects receiving methylprednisolone, a stratified analysis was conducted using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Data were collected using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), version 14.0.18 [21], a standardized platform that ensures data integrity and traceability. Subsequently, all statistical analysis was performed in R Studio 1.3.1056, STATA 14, and IBM SPSS 28 for MAC, ensuring replicability and methodological robustness [20].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Comparison Between Patients Treated With and Without Methylprednisolone

A total of 3239 patients were included in this study. In the original cohort, patients treated with methylprednisolone were slightly older (mean age 61.8 ± 12.7 vs. 60.6 ± 13.2 years; p = 0.010) and more frequently male (71.0% vs. 66.8%; p = 0.011) compared with those who did not receive methylprednisolone (Table 1). After propensity score matching, these differences were no longer statistically significant, with similar distributions of age (61.4 ± 12.9 vs. 60.6 ± 13.2 years; p = 0.096) and male sex (69.2% vs. 66.8%; p = 0.169) between groups. In the original cohort, patients who received methylprednisolone presented a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension (47.6% vs. 43.5%; p = 0.020), diabetes mellitus (25.5% vs. 18.8%; p < 0.001), and obesity (41.9% vs. 29.1%; p < 0.001) compared with those who did not receive methylprednisolone. These differences were not observed in the matched cohort, where the prevalence of hypertension (45.6% vs. 43.5%; p = 0.267), diabetes mellitus (19.9% vs. 18.8%; p = 0.466), and obesity (33.6% vs. 29.1%; p = 0.009) showed minimal variation between groups. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes comparing the methylprednisolone and non-methylprednisolone groups before and after propensity score matching analysis.

In the original cohort, patients in the methylprednisolone group required higher oxygen concentrations, with a significantly greater mean FiO2 (68.6 ± 25.6% vs. 61.4 ± 27.6%; p < 0.001), and exhibited slightly higher PaO2 values (77.2 ± 27.7 mmHg vs. 74.6 ± 25.5 mmHg; p = 0.004) compared with those who did not receive methylprednisolone. In the matched cohort, FiO2 remained significantly higher in the methylprednisolone group (65.5 ± 25.3% vs. 61.4 ± 27.6%; p < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was observed in PaO2 levels (75.6 ± 24.8 mmHg vs. 74.6 ± 25.5 mmHg; p = 0.268) (Table 1). Countries in the original and matched cohorts, categorized by methylprednisolone use and RTI-ICU, are described in Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2).

In the original cohort, patients treated with methylprednisolone more frequently received tocilizumab (22.1% vs. 17.2%; p < 0.001) and required invasive mechanical ventilation (81.7% vs. 65.2%; p < 0.001) and prone positioning (67.4% vs. 45.2%; p < 0.001) compared with those who did not receive methylprednisolone (Table 1). They also had longer ICU stays (19.3 ± 16.2 vs. 15.5 ± 14.3 days; p < 0.001), longer total hospital stays (30.1 ± 21.8 vs. 25.3 ± 20.3 days; p < 0.001), and higher mortality (34.0% vs. 28.9%; p = 0.002).

In the matched cohort, these patterns remained consistent: patients receiving methylprednisolone continued to show higher rates of invasive mechanical ventilation (80.3% vs. 65.2%; p < 0.001), pronation (66.0% vs. 45.2%; p < 0.001), longer ICU stays (19.3 ± 16.6 vs. 15.5 ± 14.3 days; p < 0.001), longer hospital stays (30.2 ± 22.2 vs. 25.3 ± 20.3 days; p < 0.001), and higher mortality (32.8% vs. 28.9%; p = 0.022), whereas the difference in tocilizumab use was no longer statistically significant (19.7% vs. 17.2%; p = 0.085) (Table 1).

3.2. Analysis of RTI-ICU

Methylprednisolone treatment was associated with a higher risk of developing RTI-ICU (OR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.33–1.91). Additionally, patients who developed RTI-ICU had higher mortality (39.2% vs. 29.2%, p < 0.001) and a significantly longer hospital stay.

The mean age of patients who developed RTI-ICU was 63 years (SD: 11.9), with the most frequent comorbidities being hypertension (47.7%, 315/660) and obesity (34.8%, 230/660) (Table 2). When comparing this group to those who did not develop RTI-ICU, a higher proportion of men was observed (73.3%, 484/660 vs. 67.6%, 1744/2579; p = 0.005), as well as higher leukocyte count (10.8, SD: 5.64 vs. 9.8, SD: 5.38; p < 0.001) and elevated C-reactive protein levels (37.9, SD: 54.7 vs. 23.5, SD: 33.5). Additionally, patients with RTI-ICU had a significantly higher average of days on IMV (24.6, SD: 15.9 vs. 9.5, SD: 11.7; p < 0.001), a longer hospital stay (40 days, SD: 24.9 vs. 24.4 days, SD: 18.7; p < 0.001), and higher ICU mortality (39.2%, 259/660 vs. 29.2%, 754/2579; p < 0.001). Baseline characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 superinfection stratified by country are described in Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes comparing the group with respiratory tract infections acquired in the intensive care unit.

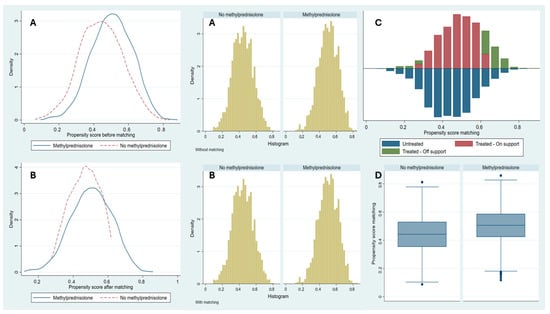

3.3. PSM

After performing PSM, a total of 2934 patients were matched in a 1:1 ratio using the nearest-neighbor method. The study groups achieved adequate balance in terms of baseline characteristics and disease severity, and the common support region was sufficiently broad to ensure the stability of estimates derived from the matching (Table 1, Figure 1). After matching, the Rubin index decreased significantly, from 51 to 13.6. Furthermore, the differences between the groups remained statistically significant when evaluated using the ATE and ATET (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Propensity score matching analysis. Notes: Before (A) and after (B) distribution of Propensity Score Matching between patients with methylprednisolone administration and patients without methylprednisolone administration. Common support region (C) between patients with and without methylprednisolone administration. Box-and-whisker plot (D) after Propensity Score Matching between patients with methylprednisolone administration and patients without methylprednisolone administration.

Table 3.

Effect of methylprednisolone administration on the occurrence of respiratory tract infections acquired in the intensive care unit.

3.4. Factors Associated with Methylprednisolone Administration and RTI-ICU Risk in the Logistic Regression Model

Methylprednisolone treatment showed a significant association with factors such as obesity (OR = 1.75, p < 0.001), diabetes (OR = 1.32, p = 0.002), and female sex (OR = 1.22, p = 0.009) (Table 4). Additionally, the risk of developing RTI-ICU was associated with increasing age (OR = 1.01, p < 0.001), elevated leukocyte levels (OR = 1.02, p < 0.001), C-reactive protein (OR = 1.01, p < 0.001), and the use of methylprednisolone (OR = 1.59, p < 0.001) and higher FiO2 support (OR = 1.01, p < 0.001). These findings highlight the influence of multiple clinical factors in the development of these complications.

Table 4.

Factors associated with treatment with Methylprednisolone and characteristics associated with the risk of respiratory tract infections acquired in the intensive care unit.

4. Discussion

We conducted a PSM analysis in a cohort of critically ill patients from Latin America and Europe. The comparison between patients treated and untreated with methylprednisolone revealed that this treatment was associated with a higher risk of developing RTI-UCI. Patients treated with methylprednisolone were predominantly obese, diabetic, and female. Our results showed that RTI-UCI was associated with higher mortality, increased need for IMV, prolonged ICU stays, elevated levels of leukocytes and C-reactive protein, and a higher comorbidity burden. Additionally, the risk of RTI-UCI was higher in older patients, with elevated leukocyte and C-reactive protein levels, and those requiring higher FiO2 support.

Although earlier in the pandemic, the hyperinflammatory response in severe COVID-19 was often referred to as a ‘cytokine storm,’ recent evidence suggests that this immunopathology more accurately reflects a dysregulated but not truly hypercytokinemic state, distinct from classical cytokine storm syndromes [3,4]. Corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone were administered in this context to attenuate excessive inflammation. However, current guidelines recommend their use specifically in patients with hypoxemia or respiratory deterioration, rather than as a generalized anti-inflammatory intervention [3,4].

RTI-UCI affects up to 50% of critically ill patients with COVID-19 [22], with mortality reaching up to 76% [22,23]. Among the most common forms of respiratory failure, NAV occurs in 18.6% of cases, followed by IMV in 10.3% [18,24]. The most relevant risk factors for the development of RTI-UCI include prolonged IMV, acute renal failure during ICU hospitalization, and a higher number of comorbidities [24]. These findings are consistent with the results of our study, which show that factors such as advanced age, a systemic inflammatory response requiring methylprednisolone, and hypoxemia requiring higher FiO2 support significantly contribute to mortality. Our results emphasize the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors, such as hypoxemia and systemic inflammation, so clinicians can implement more effective therapeutic strategies in the management of these patients.

Treatment with methylprednisolone was associated with a greater need for ventilatory support and a longer ICU stay. These findings may be related to the higher comorbidity burden observed in the treated patients, such as obesity and diabetes, conditions known to be associated with worse clinical prognosis. Although this analysis did not show a direct association between methylprednisolone use and mortality, its administration in patients with IRT-UCI was linked to an increase in MV duration and ICU stay. This suggests that, while methylprednisolone has anti-inflammatory effects, its benefit may be limited in certain subgroups of patients. Additionally, factors such as advanced age, elevated leukocyte and C-reactive protein levels, and increased FiO2 support contributed to a higher risk of developing RTI-UCI and complicated clinical outcomes. These results highlight the importance of comprehensive management that includes reducing comorbidities and monitoring inflammatory markers to optimize treatment in critically ill patients [6,8,10,18].

Corticosteroids in critically ill patients with COVID-19 are used to modulate the disproportionate inflammatory response characteristic of the disease. However, the findings of previous studies are varied. Pinzon et al. [25], in an ambispective cohort study, reported that the use of methylprednisolone in patients with ARDS reduced survival by 29.5% compared to dexamethasone. In contrast, Wagner et al. [7], through a systematic review, identified a protective effect of methylprednisolone on 30-day mortality (RR 0.51; 95% CI: 0.24–1.07), while Morsali et al. [26] reported a reduction in the risk of death in patients treated with methylprednisolone compared to standard treatment (HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.47–0.90). In our study, no significant difference in mortality was observed between the methylprednisolone-treated and untreated groups in the adjusted analysis. However, the group receiving this treatment had a longer hospital and ICU stay. These findings suggest that, although methylprednisolone may have anti-inflammatory benefits, its administration may be associated with greater disease severity and prolonged recovery in patients with severe COVID-19 [27,28].

Methylprednisolone shows greater distribution in lung tissue and a higher affinity for intracellular glucocorticoid receptors, which may enhance its local anti-inflammatory effect, whereas dexamethasone has a longer systemic half-life and predominantly systemic rather than pulmonary bioavailability [12,13,14,15,29]. This pharmacological heterogeneity may have clinical implications, as recent multicenter evidence has shown that dexamethasone use in severe COVID-19 is associated with a higher risk of ICU-acquired respiratory tract infections (OR 1.64; 95% CI 1.37–1.97), particularly ventilator-associated pneumonia [17]. These differences could partially explain the variability in outcomes across studies evaluating different corticosteroid regimens and support the rationale for specifically assessing methylprednisolone in our study [12,13,14,15,17,30].

Aljuhani et al. [9] conducted a PSM analysis in 198 patients treated with dexamethasone and 66 with methylprednisolone in the ICU. They found that the use of methylprednisolone was associated with a higher frequency of multiorgan dysfunction on the third day of admission (beta coefficient: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.02–0.32; p = 0.03) and hospital-acquired infection (OR 2.17; 95% CI: 1.01–4.66; p = 0.04). On the other hand, Ko et al. [10] reported that in patients requiring IMV, mortality was 42% lower in the methylprednisolone-treated group compared to the dexamethasone group (HR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.235–0.956; p = 0.038). Our results confirm a longer ICU stay and greater MV duration in patients treated with methylprednisolone, matched through a rigorous statistical analysis. However, they also emphasize the need for further research to evaluate the long-term effects and risks associated with this treatment in different patient subgroups [9,10,18]. Although findings in the medical literature are heterogeneous, the differences in potency and pharmacokinetics between methylprednisolone and dexamethasone may influence the observed outcomes [30,31,32,33]. Methylprednisolone has an intermediate half-life (35–39 h), lower mineralocorticoid activity, and lower potency compared to dexamethasone [34,35,36,37]. Therefore, the choice between these corticosteroids should consider both the pharmacological profile and the individual characteristics of the patient.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study was based on a prospective, multicenter collection, covering a representative sample of ICUs in Latin America and Europe. International guidelines implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic facilitated the standardization of treatments. However, the treatment with methylprednisolone was determined by the attending physician, leading to variability in dosing and treatment duration. In most protocols, the dose ranged from 0.5 to 1 mg/kg of body weight per day, administered over 5 to 10 days, depending on the patient’s clinical response [12,13,14,15,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Despite using PSM to minimize selection bias and balance baseline characteristics between treated and untreated groups, some unobserved or unmeasured factors may have influenced the results. While this method reduces observational bias, it does not eliminate the impact of unconsidered variables. Additionally, data collection was performed by attending physicians through medical record review, which could introduce variability in the quality and accuracy of the information. However, a double-check process was implemented during the transcription of data into the electronic database to mitigate potential errors. The main limitations of the study include the heterogeneity in dosing and treatment duration, as well as the presence of unmeasured biases despite using PSM.

Although propensity score matching substantially reduced baseline differences between groups, some residual imbalances persisted—particularly in obesity and markers of greater disease severity, such as higher oxygen requirements and an increased need for invasive mechanical ventilation. These factors may have contributed to the differences observed in clinical outcomes. Consequently, the results should be interpreted with caution, acknowledging that patients who received methylprednisolone likely represented a subgroup with more severe disease, which could have partially influenced the higher mortality rates and longer hospital stays observed in this group.

5. Conclusions

Methylprednisolone treatment is associated with a higher risk of ICU-related respiratory tract infections (RTI-UCI) in critically ill patients with COVID-19. RTI-UCI was linked to higher mortality, increased need for invasive mechanical ventilation, prolonged ICU stay, elevated leukocyte and C-reactive protein levels, and a higher comorbidity burden. Although propensity score matching reduced most baseline differences, residual imbalances—particularly in obesity and markers of disease severity—may have influenced the outcomes. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Overall, the results underscore the need for clinical strategies focused on more stringent monitoring and careful patient selection for methylprednisolone use, considering individual risk factors to minimize associated complications. Further studies are warranted to better define the optimal dose, timing, and safety profile of this corticosteroid.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid5120204/s1. Table S1: Countries in the original and matched cohort according to methylprednisolone use; Table S2: Countries in the original and matched cohort according to respiratory tract infections acquired in the intensive care unit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T.-Q., A.B., A.R., and L.F.R.; methodology, E.T.-Q., A.B. and L.F.R.; software, E.T.-Q. and A.B.; validation, E.G.-G., E.D., M.B., J.S.-V., R.F., A.A.-M., L.S., Á.E., A.L.-V., R.J.-G., I.S., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; formal analysis, E.T.-Q., A.B., and L.F.R.; investigation, E.T.-Q., A.B., and L.F.R.; resources, A.B., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; data curation, E.T.-Q. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T.-Q., A.B., E.G.-G., E.D., I.S., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; writing—review and editing, E.G.-G., E.D., M.B., J.S.-V., R.F., A.A.-M., L.S., Á.E., A.L.-V., R.J.-G., I.S., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; visualization, I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; supervision, E.T.-Q., A.B., E.G.-G., E.D., M.B., J.S.-V., R.F., A.A.-M., L.S., Á.E., A.L.-V., R.J.-G., I.S., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; project administration, E.T.-Q., A.B., E.G.-G., E.D., I.S., I.M.-L., A.R., and L.F.R.; funding acquisition, A.B., and L.F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study receive funding from the Universidad de La Sabana under the following grant: MED-311-2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the current Helsinki Declaration, as well as local, regional, and international regulations pertaining to clinical research, including Colombian Law on Biomedical Research. The Ethics Committee approved the study of the Clínica Universidad de La Sabana (IRB#2020AN28) and Hospital Joan XXIII (IRB#CEIM/066/2020), approval date: 29 May 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

All data were anonymized, allowing the requirement for informed consent to be waived. Treatment decisions were not standardized between centers; therefore, they were left to the discretion of the attending physicians.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are most thankful for the Universidad de La Sabana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Umakanthan, S.; Sahu, P.; Ranade, A.V.; Bukelo, M.M.; Rao, J.S.; Abrahao-Machado, L.F.; Dahal, S.; Kumar, H.; Kv, D. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. [Updated 2024]. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Merad, M.; Blish, C.A.; Sallusto, F.; Iwasaki, A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 2022, 375, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boechat, J.L.; Chora, I.; Morais, A.; Delgado, L. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 immunopathology—Current perspectives. Pulmonology 2021, 27, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Choi, A.Y.; Kopp, J.B.; Winkler, C.A.; Cho, S.K. Review of COVID-19 Therapeutics by Mechanism: From Discovery to Approval. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Su, L.; Wu, W.; Qiao, Q.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Efficacy of different doses of corticosteroids in treating severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Virol J. 2024, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Griesel, M.; Mikolajewska, A.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Fischer, A.L.; Stegemann, M.; Spagl, M.; Nair, A.A.; Daniel, J.; Fichtner, F.; et al. Systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19: Equity-related analyses and update on evidence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, CD014963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salton, F.; Confalonieri, P.; Centanni, S.; Mondoni, M.; Petrosillo, N.; Bonfanti, P.; Lapadula, G.; Lacedonia, D.; Voza, A.; Carpene, N.; et al. Prolonged higher dose methylprednisolone versus conventional dexamethasone in COVID-19 pneumonia: A randomised controlled trial (MEDEAS). Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2201514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljuhani, O.; Korayem, G.B.; Altebainawi, A.F.; AlMohammady, D.; Alfahed, A.; Altebainawi, E.F.; Aldhaeefi, M.; Badreldin, H.A.; Vishwakarma, R.; Almutairi, F.E.; et al. Dexamethasone versus methylprednisolone for multiple organ dysfunction in COVID-19 critically ill patients: A multicenter propensity score matching study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.J.; Wu, C.; Mehta, N.; Wald-Dickler, N.; Yang, W.; Qiao, R. A Comparison of Methylprednisolone and Dexamethasone in Intensive Care Patients with COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 36, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaiman, K.; Aljuhani, O.; Korayem, G.B.; Altebainawi, A.; Alharbi, R.; Assadoon, M.; Aldhaeefi, M.; Badreldin, H.A.; Vishwakarma, R.; Almutairi, F.E.; et al. Evaluation of the use of methylprednisolone and dexamethasone in asthma critically ill patients with COVID-19: A multicenter cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Qiao, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of glucocorticoids treatment in severe COVID-19: Methylprednisolone versus dexamethasone. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi Chaharom, F.; Pourafkari, L.; Ebrahimi Chaharom, A.A.; Nader, N.D. Effects of corticosteroids on COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 72, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latarissa, I.R.; Rendrayani, F.; Iftinan, G.N.; Suhandi, C.; Meiliana, A.; Sormin, I.P.; Barliana, M.I.; Lestari, K. The Efficacy of Oral/Intravenous Corticosteroid Use in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2024, 16, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, C.; Hu, W.; Lu, D.; Chen, C.; Gong, S.; Yan, J.; Mao, W. Efficacy and Safety of Glucocorticoid in the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome caused by COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Investig. Med. 2023, 46, E03–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Ruiz-Botella, M.; Martín-Loeches, I.; Jimenez Herrera, M.; Solé-Violan, J.; Gómez, J.; Bodí, M.; Trefler, S.; Papiol, E.; Díaz, E.; et al. Deploying unsupervised clustering analysis to derive clinical phenotypes and risk factors associated with mortality risk in 2022 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Spain. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.F.; Rodriguez, A.; Bastidas, A.; Parra-Tanoux, D.; Fuentes, Y.V.; García-Gallo, E.; Moreno, G.; Ospina-Tascon, G.; Hernandez, G.; Silva, E.; et al. Dexamethasone as risk-factor for ICU-acquired respiratory tract infections in severe COVID-19. J. Crit. Care 2022, 69, 154014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Minko, T. Recent Developments on Therapeutic and Diagnostic Approaches for COVID-19. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, A.C.; Metersky, M.L.; Klompas, M.; Muscedere, J.; Sweeney, D.A.; Palmer, L.B.; Napolitano, L.M.; O’Grady, N.P.; Bartlett, J.G.; Carratala, J.; et al. Management of Adults with Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e61–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzé, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Povoa, P.; Makris, D.; Artigas, A.; Bouchereau, M.; Lambiotte, F.; Metzelard, M.; Cuchet, P.; Geronimi, C.B.; et al. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the incidence of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections: A European multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyt, C.E.; Sahnoun, T.; Gautier, M.; Vidal, P.; Burrel, S.; de Chambrun, M.P.; Chommeloux, J.; Desnos, C.; Arzoine, J.; Nieszkowska, A.; et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring ECMO: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.F.; Rodriguez, A.; Fuentes, Y.V.; Duque, S.; García-Gallo, E.; Bastidas, A.; Serrano-Mayorga, C.C.; Ibanez-Prada, E.D.; Moreno, G.; Ramirez-Valbuena, P.C.; et al. Risk factors for developing ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infection in patients with severe COVID-19: A multinational, multicentre study, prospective, observational study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzón, M.A.; Ortiz, S.; Holguín, H.; Betancur, J.F.; Cardona Arango, D.; Laniado, H.; Arias, C.A.; Munoz, B.; Quiceno, J.; Jaramillo, D.; et al. Dexamethasone vs methylprednisolone high dose for COVID-19 pneumonia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsali, M.; Doosti-Irani, A.; Amini, S.; Nazemipour, M.; Mansournia, M.A.; Aliannejad, R. Comparison of corticosteroids types, dexamethasone, and methylprednisolone in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Glob. Epidemiol. 2023, 6, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Chen, D.; Gao, F.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, R.; Huang, M. Efficacy of corticosteroids in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2381086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.Y.; Lin, H.H.; Huang, C.T.; Kuo, P.H.; Wu, H.D.; Yu, C.J. Exploring the heterogeneity of effects of corticosteroids on acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, Y.; Li, L.; Li, C. Methylprednisolone or dexamethasone? How should we choose to respond to COVID-19?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2023, 102, e34738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haan, B.J.; Blackmon, S.N.; Cobb, A.M.; Cohen, H.E.; DeVier, M.T.; Perez, M.M.; Winslow, S.F. Corticosteroids in critically ill patients: A narrative review. Pharmacotherapy 2024, 44, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapugi, M.; Cunningham, K. Corticosteroids. Orthop. Nurs. 2019, 38, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbison, B.; López-López, J.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Miller, T.; Angelini, G.D.; Lightman, S.L.; Annane, D. Corticosteroids in septic shock: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzardella, A.; Motos, A.; Vallverdú, J.; Torres, A. Corticosteroids in sepsis and community-acquired pneumonia. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed. 2023, 118, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, F.; Araf, Y.; Hosen, M.J. Corticosteroids for COVID-19: Worth it or not? Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camirand-Lemyre, F.; Merson, L.; Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan, B.K.; Burrell, A.J.C.; Citarella, B.W.; Domingue, M.P.; Levesque, S.; Usuf, E.; Wils, E.-J.; Ohshimo, S.; et al. Implementation of Recommendations on the Use of Corticosteroids in Severe COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Group. Higher dose corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 who are hypoxic but not requiring ventilatory support (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granholm, A.; Kjær, M.N.; Munch, M.W.; Myatra, S.N.; Vijayaraghavan, B.K.T.; Cronhjort, M.; Wahlin, R.R.; Jakob, S.M.; Cioccari, L.; Vesterlund, G.K.; et al. Long-term outcomes of dexamethasone 12 mg versus 6 mg in patients with COVID-19 and severe hypoxaemia. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 48, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, A.; Venkatesh, B. Higher-dose dexamethasone for patients with COVID-19 and hypoxaemia? Lancet 2023, 401, 1474–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).