Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic initially focused clinical efforts on hospitalized patients. However, as the pandemic progressed, attention shifted to outpatients who often experience milder symptoms yet still contribute to viral transmission. This scoping review aimed to document and evaluate the clinical outcomes assessed in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving outpatients with COVID-19, identifying gaps and areas for improvement in trial design. This review followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. A comprehensive search of four electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Web of Science) was conducted for RCTs published between December 2019 and December 2023. Studies were included if they involved outpatients with confirmed COVID-19 and reported clinical outcomes. Data were extracted from eligible studies, and outcomes were categorized using the COMET taxonomy. A total of 91 studies were included, representing a wide geographical distribution, with the USA, Iran, and Brazil contributing the most studies. The most frequently investigated treatments included hydroxychloroquine, fluvoxamine, convalescent plasma, and ivermectin. Key outcomes focused on hospitalization rates, symptom resolution, and disease progression. Mortality, although less common in outpatients, was reported in 65 studies, underscoring the importance of outpatient interventions. This review highlights the need for standardized outcome measures in outpatient COVID-19 trials.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, initially focused clinical and research efforts on hospitalized patients with severe illness requiring intensive care [1]. This emphasis was essential for managing critically ill patients and preventing healthcare systems from collapsing due to the surge of patients experiencing severe respiratory distress [2,3]. High mortality rates among hospitalized patients led to significant investments in clinical trials testing antiviral drugs, immunomodulatory therapies, and other interventions to reduce mortality [4,5,6,7].

As the pandemic progressed, attention shifted to outpatients, who make up most COVID-19 cases and typically experience milder symptoms [8]. These patients, while not critically ill, can still face significant health impacts and contribute to ongoing transmission within the community [9,10]. Managing outpatients can reduce hospitalizations through early interventions, improve recovery times, and mitigate long-term effects such as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), commonly known as long COVID, which includes persistent symptoms like fatigue and respiratory issues [11]. With the rollout of vaccines, outpatient management became even more important. Vaccines reduce the severity of illness and hospitalizations, but breakthrough infections still occur, especially with milder symptoms, making outpatient monitoring critical for understanding vaccine effectiveness and managing long-term symptoms [12,13,14].

Outpatients, though less severely ill, play a key role in the pandemic by contributing to transmission and, in some cases, progressing to severe disease. Understanding their clinical outcomes is vital for evaluating therapeutic interventions and public health strategies [15]. The variability in primary and secondary outcomes, ranging from symptom resolution to long-term health impacts, makes it necessary to review trial methodologies to guide patient care and public health responses. Even as the pandemic subsides, monitoring COVID-19 outcomes remains crucial due to long COVID, the emergence of new variants, and the ongoing need for global preparedness [16,17,18]. This scoping review aimed to document and critically evaluate clinical outcomes in controlled trials of outpatients with COVID-19, identifying patterns, gaps, and areas for improvement in clinical trial design.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist, ensuring transparency and consistency throughout the review process [19].

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies. This search was performed in four major electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science. These databases were chosen for their extensive coverage of biomedical literature and clinical trials. The search encompassed studies published from January 2020 to December 2023, capturing the period from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to the present. The search strategy utilized a combination of keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH terms) to ensure thorough retrieval of relevant studies. Key search terms included “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “outpatients,” “clinical trials,” and “randomized controlled trials”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) combined search terms and refined the search results.

Additionally, the references of identified studies and relevant reviews were manually searched to identify any additional studies that might have been missed during the electronic database search. This exhaustive search strategy aimed to capture all relevant studies to provide a comprehensive review of the literature.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We applied strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the included studies’ relevance and quality. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving outpatients with confirmed COVID-19; (2) studies reporting at least one clinical outcome; and (3) articles published in English. A clinical outcome is defined as any measurable change in health or quality of life resulting from an intervention, such as symptom resolution, hospitalization rates, time to recovery, or mortality. The focus on RCTs ensured the inclusion of high-quality evidence from well-designed studies.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) studies involving only hospitalized patients or inpatients; (2) non-randomized studies, observational studies, case series, and case reports; (3) studies that did not report specific clinical outcomes; (4) studies reporting only virological outcomes, such as viral load, viral clearance rates, or viral shedding duration, without any clinical correlates; and (5) studies focusing exclusively on pharmacokinetic outcomes, such as drug absorption rates, distribution, metabolism, or excretion parameters. These exclusion criteria were applied to maintain the focus on outpatient settings and to ensure the inclusion of studies that provide clear and measurable clinical outcomes relevant to patient care and management. This rigorous selection process was designed to minimize bias and ensure the relevance and quality of the included studies.

2.3. Study Selection

The study selection process involved several steps to ensure a thorough and unbiased selection of relevant studies. Initially, the titles and abstracts of all identified studies were independently screened by two reviewers (CSK and DSR). This step aimed to quickly assess the relevance of each study based on the title and abstract and to exclude clearly irrelevant studies. A standardized Excel spreadsheet was used to record decisions and comments for this initial screening, facilitating organization and traceability.

Studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria or where there was uncertainty regarding their relevance were retrieved for full-text assessment. The full-text articles were then carefully assessed for eligibility based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This step involved a detailed evaluation of each study to confirm that it met all the necessary criteria for inclusion. Data from this stage were also recorded in the Excel spreadsheet to ensure consistency and transparency.

Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion or consulting a third reviewer (SSH) to reach a consensus. Using a third reviewer ensured that all disagreements were thoroughly examined and decisions were made objectively. This rigorous and systematic approach was designed to minimize bias and ensure that only relevant studies were included in the review.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (CSK and DSR) conducted data extraction independently using a standardized data extraction form designed to ensure consistency and completeness throughout the extraction process. The extracted data encompassed a broad range of study characteristics, including the author, year of publication, and country. Information on the type of intervention was also recorded to understand the nature of the treatments being evaluated.

Both primary and secondary clinical outcomes were extracted from the studies. The standardized data extraction form was pre-tested to ensure clarity and comprehensiveness, involving a pilot phase where the form was applied to a small sample of studies to identify any potential ambiguities or gaps.

Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion throughout the data extraction process. In cases where a consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (SSH) was consulted to provide an independent judgment. This multi-step approach ensured that all extracted data were accurate and reliable, thereby enhancing the validity of the review findings. The review aimed to provide a solid foundation for subsequent analysis and synthesis by systematically extracting data on study characteristics and treatment outcomes. This rigorous and detailed approach ensured the accuracy and reliability of the extracted data, facilitating a robust evaluation of the studies included in the review.

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Extracted data were synthesized narratively and quantitatively to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical outcomes evaluated in the included studies. The primary and secondary outcomes were categorized and described based on the data extracted. This narrative synthesis detailed the diversity of outcomes and methodologies used across studies, highlighting patterns and gaps.

An in-depth assessment of the outcomes evaluated in a random sample of 20 studies was conducted to develop a list of generic outcome categories defined by the treatment effect they aim to capture rather than the specific measurement instrument. Two reviewers (CSK and SSH) categorized each of the extracted outcomes within these generic outcome categories. When the evaluated outcomes did not fit into any existing categories, new generic outcome categories were developed based on consensus among the reviewers. This iterative process ensured that all relevant outcomes were appropriately categorized. The instruments used for the quantification of each outcome were also captured to provide a comprehensive understanding of the measurement tools employed. Disagreements in categorization were resolved through discussion with another reviewer (BRC).

Finally, the generic outcomes were further classified according to the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) taxonomy [20], which provides a standardized framework for outcome classification. This systematic approach to outcome grouping and classification facilitated a thorough and organized synthesis of the diverse treatment outcomes evaluated across studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

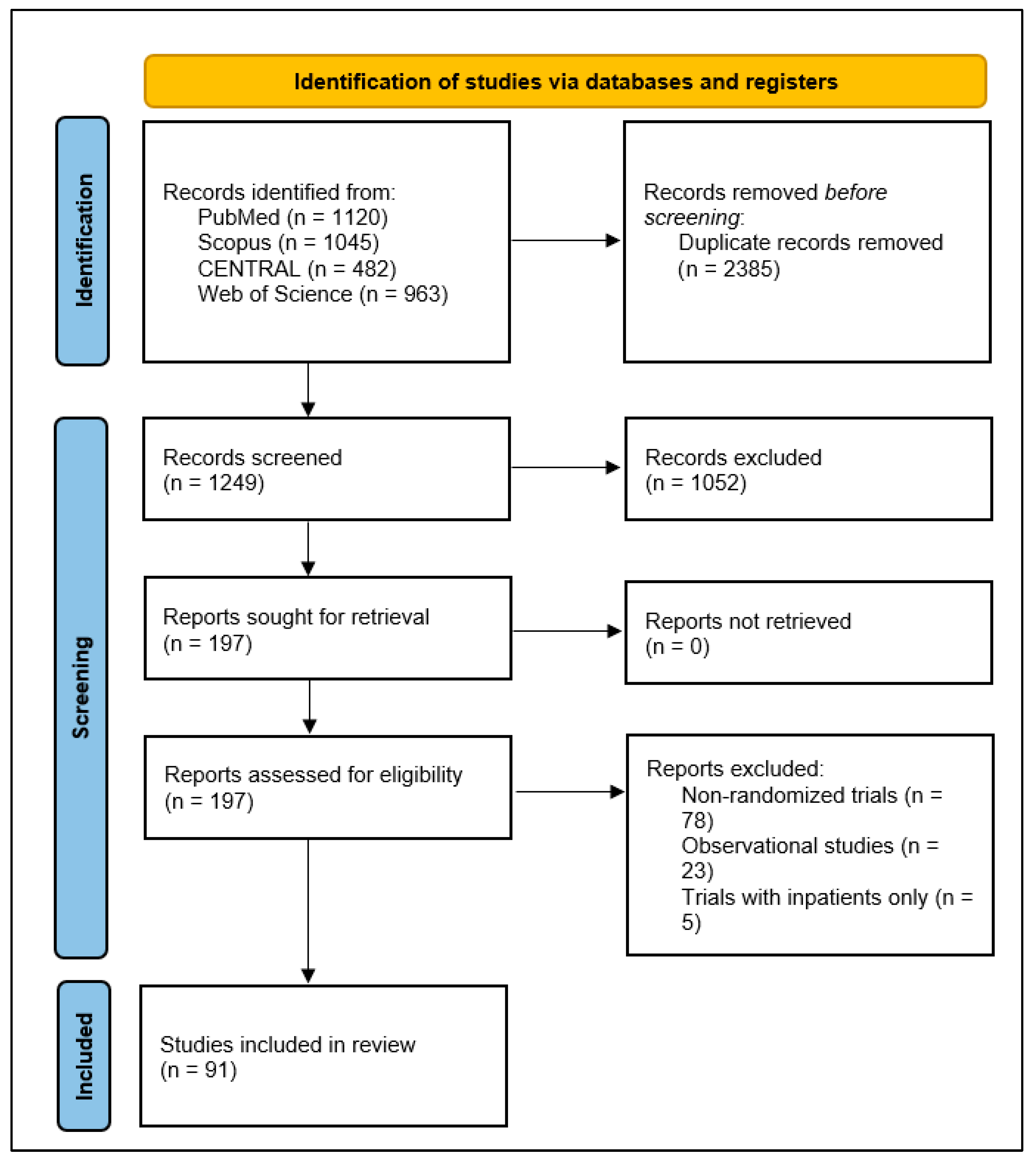

A comprehensive literature search yielded a total of 1249 studies initially identified through database searches. After removing duplicate records, the titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened for relevance. This screening process led to the selection of 197 full-text articles for detailed eligibility assessment. Of these, 91 studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). These studies were conducted across various countries, reflecting a wide geographical distribution of research efforts. The highest percentage was from the USA, which contributed 30 studies, followed by Iran with 10 studies, Brazil with 8 studies, Canada with 4 studies, and the UK with 4 studies. Additionally, 18 studies were conducted in two or more countries.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening, and inclusion process for studies in the scoping review of clinical outcomes assessed in outpatient COVID-19 randomized controlled trials.

The included studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] explored a wide range of interventions to manage COVID-19 in outpatient settings. The most frequently investigated intervention was hydroxychloroquine (with or without azithromycin), featured in 9 studies. This was followed by fluvoxamine in 7 studies and convalescent plasma in 6. Ivermectin and favipiravir were each examined in 5 studies, while herbal medicine was investigated in 4 studies. Molnupiravir was examined in 3 studies. Additionally, other interventions included various pharmacological treatments and complementary medicines, highlighting the diversity of strategies being tested globally. Detailed information for each included study is available in the appendix (Table S1).

3.2. Outcome Grouping and Classification

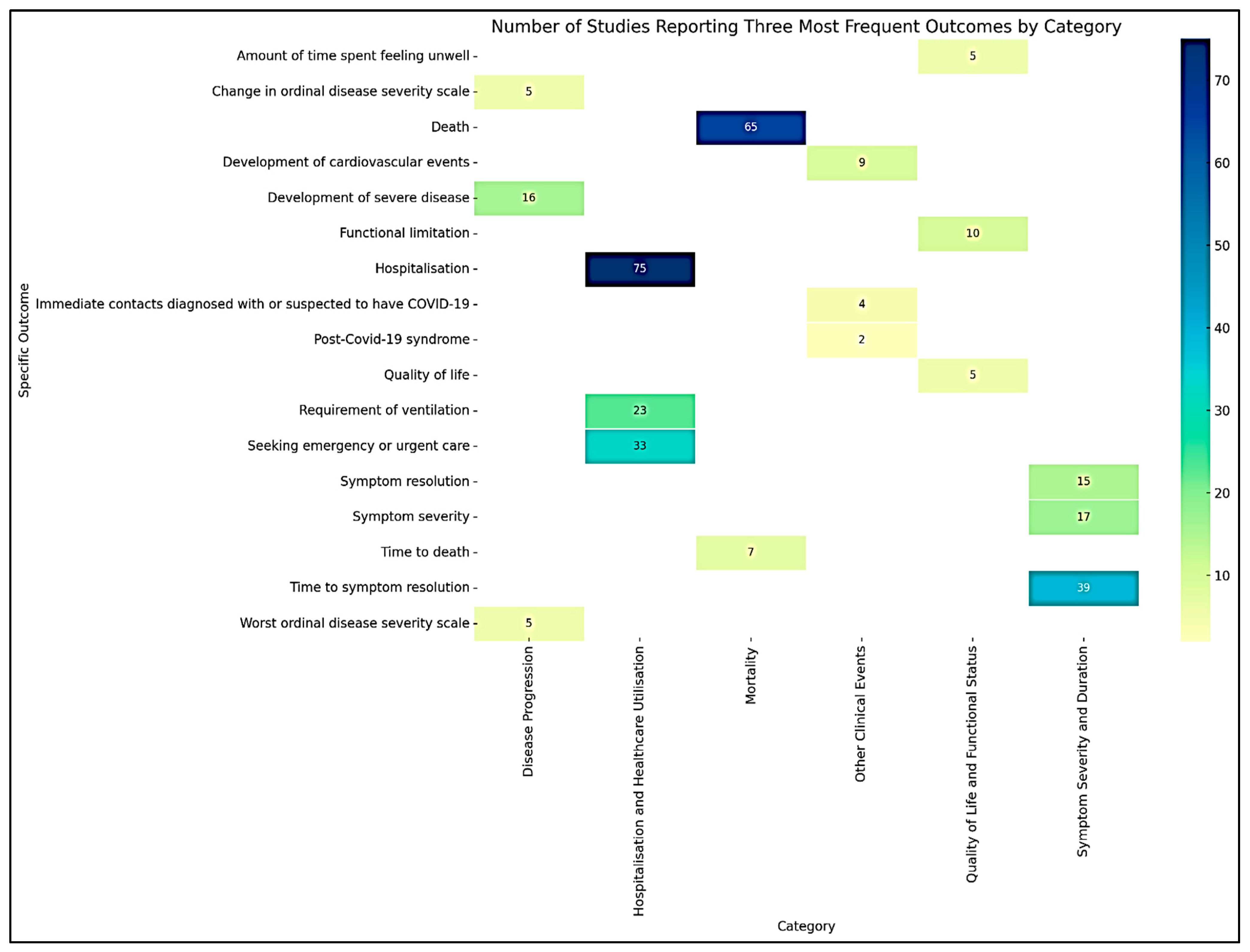

The extracted outcomes from the included studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] were systematically categorized into six generic outcome categories based on their nature and type. This categorization facilitated a structured analysis and synthesis of the diverse treatment outcomes reported across studies. A summary of the six major outcome categories, including the number and proportion of studies reporting each category and their most frequently assessed outcomes, is presented in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the heatmap illustrating the number of studies reporting the three most frequent outcomes within each category of COVID-19 treatment outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of outcome categories and frequency of reporting in randomized controlled trials of outpatient COVID-19 interventions.

Figure 2.

Heatmap visualizing the number of studies reporting the three most frequent outcomes by category.

3.2.1. Symptom Severity and Duration

The Symptom Severity and Duration category included several outcomes related to the intensity and persistence of COVID-19 symptoms reported in 71 studies. Specific outcomes in this category included:

- Symptom Severity: Measured using various scales to quantify the intensity of symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue.

- Change in Symptom Severity Scale: Assessed by tracking improvements or worsening in symptom scores over time.

- Symptom Duration: The length of time patients experienced symptoms, highlighting the persistence of illness.

- Symptom Resolution: Defined as the complete disappearance of symptoms, indicating recovery.

- Symptom Presence: Simply noting whether specific symptoms were present or absent during the study period.

- Time to Initial Reduction of Symptom Severity: The time it took from the start of the intervention for patients to experience a noticeable decrease in symptom severity.

- Time to Symptom Resolution: The duration it took for symptoms to disappear completely, indicating recovery.

- Fever-Free Days: The number of days patients were free from fever.

- Dyspnea: Instances of difficulty in breathing were reported during the study.

The most frequently reported outcome in this category was time to symptom resolution, reported in 39 studies. The second most common outcome was symptom severity, reported in 17 studies. The third most frequent outcome was symptom resolution, reported in 15 studies.

3.2.2. Disease Progression

This category included outcomes that captured the trajectory of the disease, either worsening or improving, reported in 31 studies. Specific outcomes included:

- Change in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale: A measure of changes in disease severity, often using scales that classify the disease into stages such as mild, moderate, or severe.

- Worst Ordinal Disease Severity Scale: The highest level of disease severity recorded during the study.

- Symptom Progression: Tracking the worsening of symptoms over time, indicating a decline in patient condition.

- Time to Improvement in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale: The duration it took for patients to show improvement on severity scales, moving from higher to lower severity categories.

- Time to Symptom Progression: The time it took for symptoms to worsen.

- Development of Severe Disease: Instances where patients progressed from a mild or moderate state to severe disease requiring intensive interventions.

- Development of New Severe Symptoms: The onset of severe symptoms that were not present at the start of the study.

- Development of New Symptoms: The onset of any new symptoms that were not present at the start of the study.

- Time to Development of Severe Disease: The time it took for patients to progress to severe disease.

- Prolonged Symptom: Symptoms that persist for an extended period.

- Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome: The occurrence of multiple organ failure.

- Shock: Instances of shock reported during the study.

The top three specific outcomes provide insights into the changes in disease severity over time. The development of severe disease was the most frequently reported outcome, as noted in 16 studies. The worst ordinal disease severity scale was reported in 5 studies. Change in the ordinal disease severity scale was also reported in 5 studies.

3.2.3. Hospitalization and Healthcare Utilization

This category focused on outcomes related to the use of healthcare resources, reflecting the burden on healthcare systems, reported in 82 studies. Specific outcomes included:

- Hospitalization: Whether patients require admission to a hospital due to worsening symptoms or complications.

- Time to Hospitalization: The time it took for patients to be admitted to a hospital.

- Length of Stay at Hospital: The duration of hospital stays.

- Hospital-Free Days: The number of days patients did not require hospitalization.

- Intensive Care Unit-Free Days: The number of days patients did not require admission to an intensive care unit.

- Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care: Instances where patients sought emergency or urgent medical care due to exacerbation of symptoms.

- Time to Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care: The time it took for patients to seek emergency or urgent care.

- Requirement of Oxygen Supplementation: The need for additional oxygen support indicates respiratory distress.

- Duration of Oxygen Supplementation: The length of time patients required oxygen support.

- Oxygen-Free Days: The number of days patients did not require oxygen supplementation.

- Requirement of Ventilation: Mechanical ventilation is needed due to severe respiratory distress.

- Requirement of Rescue Therapy: Instances where patients needed additional therapy due to lack of response to standard treatment.

- Duration of Ventilation: The length of time patients required mechanical ventilation.

- Ventilator-Free Days: The number of days patients did not require mechanical ventilation.

- Admission to Intensive Care Unit: The need for intensive care support due to severe illness.

- Time to an Emergency Visit Lasting More Than 6 Hours: The time it took for patients to have an emergency visit lasting more than 6 h.

- Respiratory Failure: Instances of respiratory system failure requiring critical intervention.

- Vasopressor-Free Days: The number of days patients did not require vasopressor support.

- Days with Ventilation: The total number of days patients were on mechanical ventilation.

The most frequent outcome was hospitalization, reported in 75 studies. Seeking emergency or urgent care was the second most common outcome reported in 33 studies. The third most frequent outcome was the requirement of ventilation, reported in 23 studies.

3.2.4. Mortality

This category was specific to outcomes related to death, capturing the ultimate adverse event in clinical studies reported in 65 studies. It included:

- Death: Any instance of death reported during the study period, providing critical data on the lethality of the disease and the effectiveness of interventions in preventing fatalities.

- Time to Death: The time it took from the start of the study or intervention to death.

The outcome death was reported in 65 studies, while time to death was reported in 7 studies.

3.2.5. Quality of Life and Functional Status

This category included outcomes that measured the impact of COVID-19 and its treatments on patients’ overall well-being and ability to perform daily activities, reported in 19 studies. Specific outcomes included:

- Quality of Life: Assessed using standardized questionnaires to evaluate the overall physical, mental, and social health of patients.

- Functional Limitation: Measuring the extent to which COVID-19 affected patients’ ability to carry out everyday activities and maintain independence.

- Time to Return to Usual Health: It took patients to return to their pre-illness state of health.

- Amount of Time Spent Feeling Unwell: The duration patients felt unwell during the study.

- Self-Reported Cure: Instances where patients reported feeling completely cured of their symptoms.

- Patient Satisfaction: Assessing patients’ satisfaction with the treatment received.

The most frequently reported outcome was functional limitation, reported in 10 studies. Quality of life was reported in 5 studies. The third most frequent outcome was the amount of time spent feeling unwell, as reported in 5 studies.

3.2.6. Other Clinical Events

This category captured specific adverse clinical events not covered by the other categories but were important for understanding the broader impact of COVID-19. Specific outcomes included:

Development of Cardiovascular Events: Tracking incidents such as heart attacks or strokes, which are critical given the known cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19.

Immediate Contacts Diagnosed with or Suspected to Have COVID-19: Instances where close contacts of the patient were diagnosed with or suspected to have COVID-19.

Post-COVID-19 syndrome: Long-term symptoms and health issues that persist after the acute phase of the infection has resolved.

The most frequently reported outcome was the development of cardiovascular events, reported in 9 studies. Immediate contact diagnosed with or suspected to have COVID-19 was the second most common outcome, reported in 4 studies. Post-COVID-19 syndrome was reported in 2 studies.

3.3. Classification with COMET Taxonomy

The outcomes illustrated above are further classified according to the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) taxonomy [20] to provide a standardized framework for categorizing and reporting health outcomes (Table 2). This classification ensures consistency, facilitates comparison across different studies, and improves the quality and transparency of research findings.

3.4. Symptom Severity and Duration

The outcomes in the “Symptom Severity and Duration” category are classified under the Physiological/Clinical core area. Specifically, Symptom Severity, Change in Symptom Severity Scale, Symptom Duration, Symptom Resolution, Symptom Presence, Time to Initial Reduction of Symptom Severity, Time to Symptom Resolution, and Fever-Free Days fall under the General Outcomes domain. Dyspnea is classified under the Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal outcomes domains.

3.5. Disease Progression

“Disease Progression” outcomes are classified under the Physiological/Clinical core area. Change in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Worst Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Symptom Progression, Time to Improvement in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Time to Symptom Progression, Development of Severe Disease, Development of New Severe Symptoms, Development of New Symptoms, Time to Development of Severe Disease, Prolonged Symptom, Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, and Shock are all categorized under the General outcomes’ domain.

3.6. Hospitalization and Healthcare Utilization

Outcomes in the “Hospitalisation and Healthcare Utilisation” category are classified under the Resource Use core area. This includes Hospitalization, Time to Hospitalization, Length of Stay at Hospital, Hospital-Free Days, Intensive Care Unit-Free Days, Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care, Time to Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care, Requirement of Oxygen Supplementation, Duration of Oxygen Supplementation, Oxygen-Free Days, Requirement of Ventilation, Requirement of Rescue Therapy, Duration of Ventilation, Ventilator-Free Days, Admission to Intensive Care Unit, Time to an Emergency Visit Lasting More Than 6 h, Respiratory Failure, Vasopressor-Free Days, and Days with Ventilation.

3.7. Mortality

The outcomes in the “Mortality” category fall under the Death core area. This includes Death and Time to Death, classified under the Mortality/survival domain.

3.8. Quality of Life and Functional Status

Outcomes in the “Quality of Life and Functional Status” category are classified under the Life Impact core area. Quality of Life is classified under the Global quality of life domain, Functional Limitation under Physical functioning, Time to Return to Usual Health, Amount of Time Spent Feeling Unwell, and Self-Reported Cure under Perceived health status, and Patient’s Satisfaction under Delivery of care.

3.9. Other Clinical Events

The “Other Clinical Events” category includes outcomes classified under different domains of the Physiological/Clinical core area. Development of Cardiovascular Events is classified under Cardiac outcomes, Immediate Contacts Diagnosed with or Suspected to Have COVID-19 under Infection and infestation outcomes, and post-COVID-19 Syndrome under General outcomes.

Table 2.

Classification of COVID-19 treatment outcomes according to the COMET taxonomy.

Table 2.

Classification of COVID-19 treatment outcomes according to the COMET taxonomy.

| Original Classification | COMET Core Area | Domain | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom Severity and Duration | Physiological/Clinical | General outcomes | Symptom Severity, Change in Symptom Severity Scale, Symptom Duration, Symptom Resolution, Symptom Presence, Time to Initial Reduction of Symptom Severity, Time to Symptom Resolution, Fever-Free Days |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal outcomes | Dyspnea | ||

| Disease Progression | Physiological/Clinical | General outcomes | Change in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Worst Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Symptom Progression, Time to Improvement in Ordinal Disease Severity Scale, Time to Symptom Progression, Development of Severe Disease, Development of New Severe Symptoms, Development of New Symptoms, Time to Development of Severe Disease, Prolonged Symptom, Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, Shock |

| Hospitalization and Healthcare Utilization | Resource Use | Resource utilization | Hospitalization, Time to Hospitalization, Length of Stay at Hospital, Hospital-Free Days, Intensive Care Unit-Free Days, Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care, Time to Seeking Emergency or Urgent Care, Requirement of Oxygen Supplementation, Duration of Oxygen Supplementation, Oxygen-Free Days, Requirement of Ventilation, Requirement of Rescue Therapy, Duration of Ventilation, Ventilator-Free Days, Admission to Intensive Care Unit, Time to an Emergency Visit Lasting More Than 6 Hours, Respiratory Failure, Vasopressor-Free Days, Days with Ventilation |

| Mortality | Death | Mortality/survival | Death, Time to Death |

| Quality of Life and Functional Status | Life Impact | Global quality of life | Quality of Life |

| Physical functioning | Functional Limitation | ||

| Perceived health status | Time to Return to Usual Health, Amount of Time Spent Feeling Unwell, Self-Reported Cure | ||

| Delivery of care | Patient’s Satisfaction | ||

| Other Clinical Events | Physiological/Clinical | Cardiac outcomes | Development of Cardiovascular Events |

| Infection and infestation outcomes | Immediate Contacts Diagnosed with or Suspected to Have COVID-19 | ||

| General outcomes | Post-COVID-19 Syndrome |

4. Discussion

This scoping review is the first to comprehensively evaluate the outcomes of clinical trials involving outpatients with COVID-19. This study addresses a critical gap in the literature by focusing on outpatient settings, as most previous reviews have concentrated on hospitalized patients. The significance of this review lies in its ability to systematically categorize and synthesize the diverse treatment outcomes reported in these trials. This detailed analysis provides a foundation for understanding the impact of COVID-19 interventions on non-hospitalized patients, which is essential for guiding future research and policy-making in managing the pandemic at the community level.

The studies included in this review represent a wide geographical distribution, with significant contributions from the USA, Iran, Brazil, Canada, and the UK. This broad geographical representation highlights the global effort to understand and manage COVID-19 effectively. The involvement of multiple countries ensures that the findings reflect a variety of healthcare settings, from high-income to low-income regions, thus providing a more inclusive picture of how COVID-19 is being tackled worldwide. Many of these studies were conducted in multiple countries, emphasizing the importance of international collaboration in research. Sharing data and findings across borders enhances the collective understanding of COVID-19, leading to more effective strategies and interventions.

Moreover, the review encompassed a wide range of treatment approaches, reflecting the various strategies being tested worldwide. Interventions investigated included widely known treatments such as hydroxychloroquine, fluvoxamine, convalescent plasma, ivermectin, and favipiravir, as well as herbal medicines and newer antiviral agents like molnupiravir. The inclusion of such a variety of treatments underscores the global scientific community’s dedication to exploring all possible avenues for managing COVID-19 in outpatient settings. This range of treatment approaches also provides a comprehensive overview of the potential options available, offering valuable insights into which treatments may be most effective and warranting further investigation.

The category of “Hospitalisation and Healthcare Utilisation” emerged as the most frequently reported outcome in this review, underscoring the significant impact of COVID-19 on healthcare resources. Among the 82 studies that focused on this category, hospitalization was the most common outcome, reported in 75 studies. This high frequency highlights the critical role that hospital admissions play in managing COVID-19, even in outpatient settings. Hospitalization is a key indicator of disease severity and the need for intensive medical intervention, reflecting the burden on healthcare systems during the pandemic. The second most common outcome within this category, namely seeking emergency or urgent care, underscores the acute nature of COVID-19 symptoms in some patients, necessitating immediate medical attention. The high rate of emergency care utilization further emphasizes the strain on healthcare resources, as emergency departments must be prepared to handle sudden increases in patient volumes. The requirement for ventilation, which was the third most frequent outcome, is particularly significant, as the need for mechanical ventilation indicates severe respiratory distress and critical illness. Managing patients requiring ventilation is resource-intensive, involving specialized equipment and healthcare personnel, and often necessitates prolonged hospital stays.

Another major category, “Symptom Severity and Duration,” included several outcomes related to the intensity and persistence of COVID-19 symptoms reported in 71 studies. This category reflects the importance of monitoring symptom trajectory in outpatient settings, where the primary goal is often to manage symptoms effectively and prevent deterioration. The most frequently reported outcome in this category was time to symptom resolution, reported in 39 studies. This outcome is crucial as it directly relates to the patient’s recovery timeline and overall well-being. Measuring the time to symptom resolution provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of treatments in alleviating symptoms and promoting quicker recovery, which is essential for reducing the burden on healthcare systems and improving patient quality of life. Symptom severity, the second most common outcome reported in 17 studies, quantifies the intensity of symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue, providing a clear picture of how the disease impacts patients on a day-to-day basis. Tracking changes in symptom severity over time helps to evaluate the efficacy of interventions in reducing the intensity of symptoms and improving patient comfort. The third most frequently reported outcome, symptom resolution, reported in 15 studies, is a definitive indicator of recovery. This outcome not only signifies the end of the acute phase of the illness but also serves as a benchmark for assessing the effectiveness of treatments in achieving full recovery.

Despite focusing on outpatient settings, the “Mortality” category was frequently reported, capturing the ultimate adverse event in clinical studies. Mortality outcomes were reported in 65 studies, indicating that even among outpatients, COVID-19 can lead to fatal outcomes. This high frequency of mortality reports underscores the serious nature of the disease and the importance of effective outpatient interventions to prevent progression to severe illness and death. Given the widespread rollout of COVID-19 vaccinations, which have significantly reduced mortality rates, one might question the continued high reporting of mortality among outpatients. However, these findings highlight that, despite vaccination efforts, there remains a substantial risk of death, particularly among vulnerable populations or those with breakthrough infections. This substantial reporting of mortality highlights the need for vigilant monitoring and aggressive management of COVID-19 symptoms in outpatient settings to reduce the risk of fatal outcomes. It also emphasizes the importance of ongoing public health measures and vaccination campaigns to mitigate the impact of COVID-19.

The “Disease Progression” category, reported in 31 studies, captured outcomes related to the trajectory of COVID-19, highlighting both worsening and improving conditions. This category provides crucial insights into how the disease evolves over time in outpatient settings. The most frequently reported outcome in this category was the development of severe disease, noted in 16 studies. This outcome is particularly significant as it indicates the proportion of patients whose condition deteriorates to a severe state, necessitating more intensive medical intervention. Tracking the development of severe disease helps understand which factors or interventions may contribute to preventing or mitigating such progression.

Encouragingly, the “Quality of Life and Functional Status” category was reported in 19 studies, reflecting the growing recognition of the importance of these outcomes in COVID-19 research. This category includes outcomes that measure the impact of COVID-19 and its treatments on patients’ overall well-being and ability to perform daily activities. Although only about two-tenths of the studies reported these outcomes, it is a positive development to see such measures being included. The most frequently reported outcome in this category was functional limitation, reported in 10 studies. Quality-of-life assessments are crucial as they provide a holistic view of how COVID-19 affects patients beyond physical symptoms. These outcomes help to understand the broader impact of the disease and its treatments on mental health, social functioning, and daily living. Incorporating quality-of-life measures in future research will enhance our understanding of the full spectrum of COVID-19’s effects and guide the development of interventions that target the disease and improve overall patient well-being.

It is noteworthy that “post-COVID-19 Syndrome” was reported in only 2 studies, despite its significant impact on patients’ long-term health. Post-COVID-19 syndrome, also known as long COVID, involves a range of persistent symptoms that can continue for weeks or months after the acute phase of the infection has resolved. The limited reporting of this outcome in the reviewed studies is concerning, given the increasing recognition of long COVID as a major public health issue. Understanding the prevalence and impact of post-COVID-19 syndrome is crucial for developing effective management strategies and providing adequate support to affected individuals. The fact that only 2 studies reported on this outcome is not sufficient to capture the full scope of long COVID’s impact. This highlights the urgent need for more research focused on the long-term effects of COVID-19, especially in outpatient settings. Future studies should prioritize including post-COVID-19 syndrome outcomes to better capture the full impact of the disease and inform the development of comprehensive care strategies for patients recovering from COVID-19.

Nevertheless, the development of cardiovascular events, which is also a component of post-COVID-19 syndrome, was reported in 9 studies. This category is significant as it highlights the broader systemic impact of COVID-19 beyond the respiratory system. Cardiovascular complications, such as myocardial infarction and strokes, have been increasingly recognized as critical issues associated with COVID-19. The fact that cardiovascular events were frequently reported underscores the need for healthcare providers to monitor and manage these potential complications in COVID-19 patients, even those treated in outpatient settings. Recognizing and addressing the cardiovascular impact of COVID-19 is crucial for comprehensive patient care and reducing the risk of severe outcomes associated with these events.

Taken together, the findings of this scoping review underscore that the lack of consistency in outcome definitions and measurement approaches across outpatient COVID-19 trials poses major barriers to evidence translation and clinical implementation. The variability observed in key outcomes—such as hospitalization, symptom resolution, and clinical improvement—prevents direct comparison between studies and weakens the development of coherent treatment guidelines. This heterogeneity also limits the ability to synthesize evidence across trials, thereby slowing the identification of truly effective outpatient interventions. To bridge this gap, future research should prioritize the development and adoption of a harmonized Core Outcome Set (COS) that ensures outcome measures are standardized, patient-centered, and clinically meaningful. Such standardization would strengthen the continuity between research, practice, and policy, ultimately enhancing the applicability and impact of outpatient COVID-19 trial findings on real-world patient care.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review is the first to comprehensively evaluate the outcomes of clinical trials involving outpatients with COVID-19, addressing a critical gap in the literature predominantly focused on hospitalized patients. By systematically categorizing and synthesizing diverse treatment outcomes, this review provides a foundation for understanding the impact of COVID-19 interventions on non-hospitalized patients. The findings highlight the significance of various outcomes, such as symptom severity and duration, disease progression, healthcare utilization, mortality, quality of life, and other clinical events. The review underscores the importance of standardizing outcomes in clinical trials to enhance comparability and the synthesis of evidence, ultimately guiding future research and policy-making in managing COVID-19 at the community level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid5120199/s1, Table S1: Summary of included studies evaluating various interventions for COVID-19 management in outpatient settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.K. and S.S.H.; methodology, C.S.K. and D.S.R.; validation, C.S.K., B.R.C. and S.S.H.; formal analysis, C.S.K.; investigation, D.S.R.; resources, B.R.C.; data curation, C.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.K.; writing—review and editing, D.S.R., B.R.C. and S.S.H.; visualization, C.S.K.; supervision, S.S.H.; project administration, C.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

As this study synthesized information from published sources, informed consent was not required.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Materials. No additional datasets were generated or analyzed beyond those reported in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duek, I.; Fliss, D.M. The COVID-19 pandemic-from great challenge to unique opportunity: Perspective. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 59, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhala, A.; Gotur, D.; Hsu, S.H.; Uppalapati, A.; Hernandez, M.; Alegria, J.; Masud, F. A Year of Critical Care: The Changing Face of the ICU During COVID-19. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2021, 17, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Arabi, Y.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Evans, L.; Citerio, G.; Fischkoff, K.; Salluh, J.; Meyfroidt, G.; Alshamsi, F.; Oczkowski, S.; et al. Managing ICU surge during the COVID-19 crisis: Rapid guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1303–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.; Vieira, A.M.; Capela, E.; Julião, P.; Macedo, A. COVID-19 fatality rates in hospitalized patients: A new systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilio, I.; Lazar Neto, F.; Lazzeri Cortez, A.; Miethke-Morais, A.; Dutilh Novaes, H.M.; Possolo de Sousa, H.; de Carvalho, C.R.R.; Shafferman Levin, A.S.; Ferreira, J.C.; Gouveia, N.; et al. Mortality over time among COVID-19 patients hospitalized during the first surge of the pandemic: A large cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasziou, P.; Sanders, S.; Byambasuren, O.; Thomas, R.; Hoffmann, T.; Greenwood, H.; van der Merwe, M.; Clark, J. Clinical trials and their impact on policy during COVID-19: A review. Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijotas-Reig, J.; Esteve-Valverde, E.; Belizna, C.; Selva-O’Callaghan, A.; Pardos-Gea, J.; Quintana, A.; Mekinian, A.; Anunciacion-Llunell, A.; Miró-Mur, F. Immunomodulatory therapy for the management of severe COVID-19. Beyond the anti-viral therapy: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapostolle, F.; Schneider, E.; Vianu, I.; Dollet, G.; Roche, B.; Berdah, J.; Michel, J.; Goix, L.; Chanzy, E.; Petrovic, T.; et al. Clinical features of 1487 COVID-19 patients with outpatient management in the Greater Paris: The COVID-call study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalau, A.; Odish, F.; Imam, Z.; Sharrak, A.; Brickner, E.; Lee, P.B.; Foglesong, A.; Michel, A.; Gill, I.; Qu, L.; et al. Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes of a Large Cohort of COVID-19 Outpatients in Michigan. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isasi, F.; Naylor, M.D.; Skorton, D.; Grabowski, D.C.; Hernández, S.; Rice, V.M. Patients, Families, and Communities COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs. In NAM Perspectives; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Shavaleh, R.; Forouhi, M.; Disfani, H.F.; Kamandi, M.; Oskooi, R.K.; Foogerdi, M.; Soltani, M.; Rahchamani, M.; Mohaddespour, M.; et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Zafar, A.; Afzal, H.; Ejaz, T.; Shamim, S.; Saleemi, S.; Subhan Butt, A. COVID-19 infection among vaccinated and unvaccinated: Does it make any difference? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, S.; Perego, M.; Tricella, G.; Poole, D.; Ranieri, V.M.; GiViTI (Italian Group for the Evaluation of Interventions in Intensive Care Medicine). SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals requiring ventilatory support for severe acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 49, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umscheid, C.A.; Margolis, D.J.; Grossman, C.E. Key concepts of clinical trials: A narrative review. Postgrad. Med. 2011, 123, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Jones, C.H.; Welch, V.; True, J.M. Outlook of pandemic preparedness in a post-COVID-19 world. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, J.J.; Williamson, P. Core outcome sets in medical research. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Elliott, J.H.; Azevedo, L.C.; Baumgart, A.; Bersten, A.; Cervantes, L.; Chew, D.P.; Cho, Y.; Cooper, T.; Crowe, S.; et al. COVID-19-Core Outcomes Set (COS) Workshop Investigators. Core Outcomes Set for Trials in People with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Baumgart, A.; Evangelidis, N.; Viecelli, A.K.; Carter, S.A.; Azevedo, L.C.; Cooper, T.; Bersten, A.; Cervantes, L.; Chew, D.P.; et al. COVID-19-Core Outcomes Set Investigators. Core Outcome Measures for Trials in People with Coronavirus Disease 2019: Respiratory Failure, Multiorgan Failure, Shortness of Breath, and Recovery. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, S.; Clarke, M.; Becker, L.; Mavergames, C.; Fish, R.; Williamson, P.R. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 96, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, A.; Millat-Martinez, P.; Corbacho-Monne, M.; Malchair, P.; Ouchi, D.; de la Sierra, A.; Camprubi, D.; Maria Grau-Pujol, B.; Vila, J.; Mata, C.; et al. High-titre methylene blue-treated convalescent plasma as an early treatment for outpatients with COVID-19: A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbharan, A.; Jordans, C.; Zwaginga, L.; Papageorgiou, G.; van Geloven, N.; van Wijngaarden, P.; den Hollander, J.; Karim, F.; van Leeuwen-Segarceanu, E.; Soetekouw, R.; et al. Outpatient convalescent plasma therapy for high-risk patients with early COVID-19: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korley, F.K.; Durkalski-Mauldin, V.; Yeatts, S.D.; Schulman, K.; Davenport, R.D.; Dumont, L.J.; El Kassar, N.; Foster, L.D.; Hah, J.M.; Jaiswal, S.; et al. SIREN-C3PO Investigators. Early Convalescent Plasma for High-Risk Outpatients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libster, R.; Pérez Marc, G.; Wappner, D.; Coviello, S.; Bianchi, A.; Braem, V.; Esteban, I.; Caballero, M.T.; Wood, C.; Berrueta, M.; et al. Early High-Titer Plasma Therapy to Prevent Severe COVID-19 in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.J.; Gebo, K.A.; Shoham, S.; Bloch, E.M.; Lau, B.; Shenoy, A.G.; Mosnaim, G.; Gniadek, T.J.; Fukuta, Y.; Wada, K.; et al. Early Outpatient Treatment for COVID-19 with Convalescent Plasma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1700–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Nirula, A.; Heller, B.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Boscia, J.; Morris, J.; Huhn, G.; Cardona, J.; Mocherla, B.; Stosor, V.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody LY-CoV555 in Outpatients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, M.; Nirula, A.; Azizad, M.; Mocherla, B.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Chen, P.; Hebert, C.; Perry, R.; Heller, B.; Wine, J.; et al. Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab in Mild or Moderate COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gonzalez-Rojas, Y.; Juarez, E.; Crespo Casal, M.; Moya, J.; Falci, D.R.; Sarkis, E.; Solis, J.; Zheng, H.; Scott, N.; et al. Early Treatment for COVID-19 with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Sotrovimab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Săndulescu, O.; Preotescu, L.L.; Rivera-Martínez, N.E.; Dobryanska, M.; Birlutiu, V.; Miftode, E.G.; Gaibu, N.; Caliman-Sturdza, O.; Florescu, S.A.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Regdanvimab in High-Risk Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac406, Erratum in Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, H.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Padilla, F.; Arbetter, D.; Templeton, A.; Seegobin, S.; Kim, K.; Ayers, M.; Kohli, A.; Brown, M.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of intramuscular administration of tixagevimab-cilgavimab for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19 (TACKLE): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreich, D.M.; Sivapalasingam, S.; Norton, T.; Ali, S.; Gao, H.; Bhore, R.; Xiao, J.; Hooper, A.T.; Hamilton, J.D.; Musser, B.J.; et al. REGEN-COV Antibody Combination and Outcomes in Outpatients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, U.C.; Adler, M.S.; Padula, A.E.M.; Hotta, L.M.; de Toledo Cesar, A.; Diniz, J.N.M.; de Freitas Santos, H.; Martinez, E.Z. Homeopathy for COVID-19 in primary care: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (COVID-Simile study). J. Integr. Med. 2022, 20, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco, S.; Voci, D.; Held, U.; Sebastian, T.; Bingisser, R.; Colucci, G.; Duerschmied, D.; Frenk, A.; Gerber, B.; Götschi, A.; et al. Enoxaparin for primary thromboprophylaxis in symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 (OVID): A randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e585–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramante, C.T.; Huling, J.D.; Tignanelli, C.J.; Buse, J.B.; Liebovitz, D.; Nicklas, J.M.; Puskarich, M.A.; Cohen, K.; Belani, H.; Anderson, J.; et al. Randomized Trial of Metformin, Ivermectin, and Fluvoxamine for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.M.; Dulko, D.; Griffiths, J.K.; Golan, Y.; Cohen, T.; Trinquart, L.; Price, L.L.; Beaulac, K.R.; Selker, H.P. Efficacy of Niclosamide vs Placebo in SARS-CoV-2 Respiratory Viral Clearance, Viral Shedding, and Duration of Symptoms Among Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2144942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemency, B.M.; Varughese, R.; Gonzalez-Rojas, Y.; Morse, C.G.; Phipatanakul, W.; Levinson, M.; Carroll, K.; Brown, T.; Choi, B.; Camargo, C.A.; et al. Efficacy of Inhaled Ciclesonide for Outpatient Treatment of Adolescents and Adults with Symptomatic COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J.M.; Brooks, M.M.; Sciurba, F.C.; Krishnan, J.A.; Bledsoe, J.R.; Kindzelski, A.; Ridker, P.M.; Rosovsky, R.P.; Hunninghake, G.M.; Lindsell, C.J.; et al. Effect of Antithrombotic Therapy on Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients with Clinically Stable Symptomatic COVID-19: The ACTIV-4B Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, F.; Virdone, S.; Sawhney, J.; Lopes, R.D.; Jacobson, B.; Arcelus, J.I.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Gibbs, H.; Himmelreich, J.C.L.; MacCallum, P.; et al. Thromboprophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard of care in unvaccinated, at-risk outpatients with COVID-19 (ETHIC): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e594–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvignaud, A.; Lhomme, E.; Onaisi, R.; Escriou, N.; Lamontagne, F.; Lacombe, K.; Brousse, V.; Malvy, D.; Chapplain, J.M.; Esteve, C.; et al. Inhaled ciclesonide for outpatient treatment of COVID-19 in adults at risk of adverse outcomes: A randomised controlled trial (COVERAGE). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ochoa, A.J.; Raffetto, J.D.; Hernandez, A.G.; Parsa, N.; Gharavi, R.; Theethira, T.G.; Kunitake, H.; Bhakta, A.; Berry, S.M.; Davis, M.; et al. Sulodexide in the Treatment of Patients with Early Stages of COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 121, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinks, T.S.C.; Cureton, L.; Knight, R.; Wang, A.; Cane, J.L.; Barber, V.S.; Black, J.; Presland, L.; Dutton, S.J.; Melhorn, J.; et al. Azithromycin versus standard care in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (ATOMIC2): An open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Brown, E.R.; Stewart, J.; Karita, H.; Khouri, M.; Hambrick, H.R.; Day, C.L.; McKittrick, N.; Baden, L.R.; Madamba, J.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin for treatment of early SARS-CoV-2 infection among high-risk outpatient adults: A randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 33, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshiddoust, R.R.; Khorshiddoust, S.R.; Hosseinabadi, T.; Ghanadi, A.; Azadmehr, A.; Rezaei, S.A.; Mortazavian, S.M.; Adibi, P. Efficacy of a multiple-indication antiviral herbal drug (Saliravira(R)) for COVID-19 outpatients: A pre-clinical and randomized clinical trial study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 149, 112729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, E.J.; Mattar, C.; Zorumski, C.F.; Stevens, A.; Schweiger, J.; Nicol, G.E.; Miller, J.P.; Yang, L.; Yingling, M.; Avidan, M.S.; et al. Fluvoxamine vs Placebo and Clinical Deterioration in Outpatients with Symptomatic COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 2292–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.W.; Naggie, S.; Boulware, D.R.; Bower, W.A.; Baughman, A.L.; Saydah, S.; Oliver, S.E.; McConnell, K.; Morey, R.E.; Craft, D.W.; et al. Effect of Fluvoxamine vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, M.R.; Schnell, P.M.; Rhoda, D.A. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial of resveratrol for outpatient treatment of mild coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitjà, O.; Corbacho-Monné, M.; Ubals, M.; Tebé, C.; Peñafiel, J.; Tobias, A.; Ballana, E.; Alemany, A.; Riera-Martí, N.; Pérez, C.A.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine for Early Treatment of Adults with Mild Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e4073–e4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naggie, S.; Boulware, D.R.; Lindsell, C.J.; Pettit, N.N.; Kanack, A.T.; Bellamy, C.H.; Kelleher, J.; Griffith, D.; Kasten, M.J.; Natarajan, K.; et al. Effect of Higher-Dose Ivermectin for 6 Days vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naggie, S.; Boulware, D.R.; Lindsell, C.J.; Pettit, N.N.; Kanack, A.T.; Bellamy, C.H.; Kelleher, J.; Griffith, D.; Kasten, M.J.; Natarajan, K.; et al. Effect of Ivermectin vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 328, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, C.E.; Pinsky, B.A.; Brogdon, J.; Chen, C.; Ruder, K.; Zhong, L.; Doan, T.; McNaughton, C.D.; Khalil, P.; Goldman, J.D.; et al. Effect of Oral Azithromycin vs Placebo on COVID-19 Symptoms in Outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskarich, M.A.; Cummins, N.W.; Ingraham, N.E.; Naud, B.M.; Floberg, J.M.; Patel, B.; Nanda, S.; Pipke, M.; Larson, R.J.; Deitchman, A.N.; et al. A multi-center phase II randomized clinical trial of losartan on symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Dos Santos Moreira Silva, E.A.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Park, J.J.H.; Forrest, J.I.; Harari, O.; Galvez, V.; Ferraz, P.; Cossi, M.S.; et al. Expression of concern—Effect of early treatment with metformin on risk of emergency care and hospitalization among patients with COVID-19: The TOGETHER randomized platform clinical trial. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 31, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Dos Santos Moreira Silva, E.A.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Park, J.J.H.; Forrest, J.I.; Harari, O.; Galvez, V.; Ferraz, P.; Cossi, M.S.; et al. Oral Fluvoxamine with Inhaled Budesonide for Treatment of Early-Onset COVID-19: A Randomized Platform Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Dos Santos Moreira-Silva, E.A.; Silva, D.C.M.; Thabane, L.; Milagres, A.C.; Ferreira, T.S.; Dos Santos, C.V.Q.; de Souza Campos, V.H.; Nogueira, A.M.R.; de Almeida, A.P.F.G.; et al. Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: The TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e42–e51, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e481; Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.G.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Mourad, A.; Lindsell, C.J.; Boulware, D.R.; McCarthy, M.W.; Thicklin, F.; Garcia Del Sol, I.T.; Bramante, C.T.; Lenert, L.A.; et al. Higher-Dose Fluvoxamine and Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients with COVID-19: The ACTIV-6 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Silva, E.; Silva, D.C.M.; Thabane, L.; Park, J.J.H.; Forrest, J.I.; Harari, O.; Galvez, V.; Ferraz, P.; Cossi, M.S.; et al. Effect of Early Treatment with Ivermectin among Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, M.S.; Ahangarkani, F.; Hill, A.; Kashaninasab, F.; Mehravaran, H.; Emadi-Baygi, M.; Haghighi-Asl, H.; Ashrafian-Bonab, M.; Rezaei, M.S.; Baradaran, A.; et al. Non-effectiveness of Ivermectin on Inpatients and Outpatients with COVID-19; Results of Two Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 919708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Freitas-Santos, R.S.; Levi, J.E.; Bertolaccini, L.F.; Scopel, D.; Gouvêa, M.L.; Cavalcanti, L.F.; Olivares, T.S.; Medeiros, A.C.; Carvalho, P.M.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin early treatment of mild COVID-19 in an outpatient setting: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating viral clearance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, J.F.; Bardin, M.C.; Fulgencio, J.; Mogelnicki, D.; Brechot, C. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of nitazoxanide for treatment of mild or moderate COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 45, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, I.; Boesen, M.E.; Cerchiaro, G.; Doram, C.; Edwards, B.D.; Ganesh, A.; Greenfield, J.; Jamieson, S.; Karnik, V.; Kenney, C.; et al. Assessing the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine as outpatient treatment of COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E693–E702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, C.P.; Pastick, K.A.; Engen, N.W.; Bangdiwala, A.S.; Abassi, M.; Lofgren, S.M.; Williams, D.A.; Okafor, E.C.; Pullen, M.F.; Nicol, M.R.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine in Nonhospitalized Adults with Early COVID-19: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, A.M.; Barney, B.J.; Greene, T.; Holubkov, R.; Olsen, C.S.; Bridges, J.; Srivastava, R.; Webb, B.; Sebahar, F.; Huffman, A.; et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial Testing Hydroxychloroquine for Reduction of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Shedding and Hospitalization in Early Outpatient COVID-19 Infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0467422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, J.C.; Bouabdallaoui, N.; L’Allier, P.L.; Gaudet, D.; Shah, B.; Pillinger, M.H.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; da Luz, P.; Verret, L.; Audet, S.; et al. Colchicine for community-treated patients with COVID-19 (COLCORONA): A phase 3, randomised, double-blinded, adaptive, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Patel, D.; Bittel, B.; Wolski, K.; Wang, Q.; Kumar, A.; Il’Giovine, Z.J.; Mehra, R.; McWilliams, C.; Nissen, S.E.; et al. Effect of High-Dose Zinc and Ascorbic Acid Supplementation vs Usual Care on Symptom Length and Reduction Among Ambulatory Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The COVID A to Z Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e210369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosaeed, M.; Alharbi, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Alqahtani, H.; Al Sulaiman, R.; Al Aithan, A.M.; Alamri, M.; Al Masood, A.; Al Mutair, A.; Al Omari, A.; et al. Efficacy of favipiravir in adults with mild COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.C.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Gbinigie, O.A.; Mbisa, J.L.; Hared, A.; Dunbar, J.K.; Petrou, S.; Holmes, J.; Gafos, M.; Preuss, M.; et al. Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): An open-label, platform-adaptive randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, J.J.; Kandel, C.; Biondi, M.J.; Barkema, R.; McDonald-Barnes, L.; Gnirke, J.; Powis, J.; Hayes, M.; Brown, K.A.; Webb, G.J.; et al. Peginterferon lambda for the treatment of outpatients with COVID-19: A phase 2, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.L.; Vaca, C.E.; Paredes, R.; Mera, J.; Webb, B.J.; Perez, G.; Oguchi, G.; Negron, C.; Sostman, H.D.; Sharma, S.; et al. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe COVID-19 in Outpatients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Simón-Campos, A.; Kaplow, R.; Aftab, B.T.; Pypstra, R.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripongboonsitti, T.; Nontawong, N.; Tawinprai, K.; Suptawiwat, O.; Soonklang, K.; Poovorawan, Y.; Mahanonda, N. Efficacy of combined COVID-19 convalescent plasma with oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor treatment versus neutralizing monoclonal antibody therapy in COVID-19 outpatients: A multi-center, non-inferiority, open-label randomized controlled trial (PlasMab). Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0325723. [Google Scholar]

- Horga, A.; Saenz, R.; Yilmaz, G.; Simón-Campos, A.; Pietropaolo, K.; Stubbings, W.J.; Collinson, N.; Ishak, L.; Zrinscak, B.; Belanger, B.; et al. Oral bemnifosbuvir (AT-527) vs placebo in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in an outpatient setting (MORNINGSKY). Future Virol. 2023, 18, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, P.; Chew, K.W.; Giganti, M.J.; Hughes, M.D.; Moser, C.; Main, M.J.; Monk, P.D.; Javan, A.C.; Li, J.Z.; Fletcher, C.V.; et al. ACTIV-2/A5401 Study Team. Safety and efficacy of inhaled interferon-β1a (SNG001) in adults with mild-to-moderate COVID-19: A randomized, controlled, phase II trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, P.; Andrews, J.R.; Bonilla, H.; Dewald, C.F.; Lu, K.; Nelson, C.W.; Yang, P.; Donohue, K.; Strohmeier, S.; Taylor, J.D.; et al. Peginterferon Lambda-1a for treatment of outpatients with uncomplicated COVID-19: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayk Bernal, A.; Gomes da Silva, M.M.; Musungaie, D.B.; Kovalchuk, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Delos Reyes, V.; Martin, E.; Williams-Diaz, A.; Brown, M.L.; Du, J.; et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of COVID-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, A.M.; Shapiro, N.I.; Wild, J.; Ginde, A.A.; Chopra, A.; Flynn, C.; Grundmeier, R.; Boulware, D.R.; Fenton, L.Z.; Ziegler, J.; et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir for treatment of non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 128, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.M.; Brown, L.K.; Chowdhury, K.; Davey, S.; Yee, P.; Ikeji, F.; Ndoutoumou, A.; Shah, D.; Lennon, A.; Rai, A.; et al. FLARE Investigators. Favipiravir, lopinavir-ritonavir, or combination therapy (FLARE): A randomised, double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial placebo-controlled trial of early antiviral therapy in COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parienti, J.J.; Prazuck, T.; Peyro-Saint-Paul, L.; Fournier, C.; Valentin, A.; Belin, L.; Le Moal, G.; Reynes, J.; Guedj, J. Effect of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Emtricitabine on nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral load burden amongst outpatients with COVID-19: A pilot, randomized, open-label phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Moreira Silva, E.A.D.S.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Singh, G.; Park, J.J.H.; Forrest, J.I.; Harari, O.; Quirino Dos Santos, C.V.; Guimarães de Almeida, A.P.F.; et al. Effect of Early Treatment with Hydroxychloroquine or Lopinavir and Ritonavir on Risk of Hospitalization Among Patients with COVID-19: The TOGETHER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e216468, Erratum in JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2130442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Moreira Silva, E.A.S.; Medeiros Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Milagres, A.C.; Ferreira, T.S.; Dos Santos, C.V.Q.; Muricy, A.C.C.; de Almeida, A.W.P.; Callegari, E.D.; et al. Early Treatment with Pegylated Interferon Lambda for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozbeh, F.; Saeedi, M.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Shabani, M.; Karkhah, S.; Teymouri, S.; Khoshnood, Z.; Roozbeh, H. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for the treatment of COVID-19 outpatients: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, A.; Salmasi, M.; Soltaninejad, F.; Salahi, M.; Javanmard, S.H.; Amra, B. Favipiravir in the Treatment of Outpatient COVID-19: A Multicenter, Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Adv. Respir. Med. 2023, 91, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, N.; Bollerup, S.; Sund, J.D.; Glamann, J.B.; Vinten, C.; Jensen, L.R.; Sejling, C.; Kledal, T.N.; Rosenkilde, M.M. Amantadine for COVID-19 treatment (ACT) study: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel Mehraban, M.S.; Shirzad, M.; Mohammad Taghizadeh Kashani, L.; Ahmadian-Attari, M.M.; Safari, A.A.; Ansari, N.; Hatami, H.; Kamalinejad, M. Efficacy and safety of add-on Viola odorata L. in the treatment of COVID-19: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 304, 116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Keyhanian, N.; Ghaderkhani, S.; Dashti-Khavidaki, S.; Shokouhi Shoormasti, R.; Pourpak, Z. A Pilot Study on Controlling Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Inflammation Using Melatonin Supplement. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 20, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdallah, S.; Mhalla, Y.; Trabelsi, I.; Sekma, A.; Youssef, R.; Bel Haj Ali, K.; Ben Soltane, H.; Yacoubi, H.; Msolli, M.A.; Stambouli, N.; et al. Twice-Daily Oral Zinc in the Treatment of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencheqroun, H.; Ahmed, Y.; Kocak, M.; Melike, Y.; Hafidi, H.; Atfi, A.; El Fatimy, R.; El Ouali Lalami, A.; Haidour, A.; Boukhari, A.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of ThymoQuinone Formula (TQF) for Treating Outpatient SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens 2022, 11, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, C.M.; Nadella, S.; Zhao, X.; Dima, R.J.; Jordan-Martin, N.; Demestichas, B.R.; Kleeman, S.O.; Ferrer, M.; Janowitz, T. Oral famotidine versus placebo in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, data-intense, phase 2 clinical trial. Gut 2022, 71, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, I.; Cauwenberghs, E.; Spacova, I.; Gehrmann, T.; Eilers, T.; Delanghe, L.; Wittouck, S.; Bron, P.A.; Henkens, T.; Gamgami, I.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of a Throat Spray with Selected Lactobacilli in COVID-19 Outpatients. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0168222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanpour, M.; Safari, H.; Mohammadpour, A.H.; Amini, Z.; Iranshahy, M.; Ashrafzadeh, M.; Zamiri, R.E.; Sahebkar, A.; Abbasi, S.H.; Ghorbani, M. Efficacy of Covexir(R) (Ferula foetida oleo-gum) treatment in symptomatic improvement of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 4504–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Iqtadar, S.; Mumtaz, S.U.; Akhtar, N.; Muhammad, A.; Ullah, H.; Hussain, A.; Ali, S.; Shah, J.; Khan, M.N.; et al. Oral Co-Supplementation of Curcumin, Quercetin, and Vitamin D3 as an Adjuvant Therapy for Mild to Moderate Symptoms of COVID-19-Results from a Pilot Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 898062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, S.H.; FitzGerald, R.; Saunders, G.; Whitehouse, T.; O’Kane, P.; Conibear, T.; Gupta, R.; Catterick, D.; Klein, N.; Berry, L.; et al. Molnupiravir versus placebo in unvaccinated and vaccinated patients with early SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK (AGILE CST-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmopoulos, A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Meglis, G.; Klein, A.L.; Gornik, H.L.; Chhatriwalla, A.K.; Shoemaker, A.; Misra, S.; Ram, C.V.; Lincoff, A.M. A randomized trial of icosapent ethyl in ambulatory patients with COVID-19. iScience 2021, 24, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, M.; Mozaffar, H.; Mesri, M.; Shokri, M.; Delaney, D.; Karimy, M. Evaluation and comparison of vitamin A supplementation with standard therapies in the treatment of patients with COVID-19. East Mediterr. Health J. 2022, 28, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, M.; Wu, W.; Moore, K.; Winchester, S.; Tu, Y.P.; Miller, C.; Kodgule, R.; Pendse, A.; Rangwala, S.; Joshi, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 accelerated clearance using a novel nitric oxide nasal spray (NONS) treatment: A randomized trial. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.E.; Pandey, N.; Chavda, P.; Singh, G.; Sutariya, R.; Sancilio, F.; Tripp, R.A. Oral Probenecid for Nonhospitalized Adults with Symptomatic Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19. Viruses 2023, 15, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasse, T.F.; Delgado, B.; Potts, J.; Abramson, D.; Fehrmann, C.; Fathi, R.; McComsey, G.A. A randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of upamostat, a host-directed serine protease inhibitor, for outpatient treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 128, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzhentsova, T.A.; Oseshnyuk, R.A.; Soluyanova, T.N.; Dmitrikova, E.P.; Mustafaev, D.M.; Pokrovskiy, K.A.; Markova, T.N.; Rusanova, M.G.; Kostina, N.E.; Agafina, A.S.; et al. Phase 3 trial of coronavir (favipiravir) in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 12575–12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, S.; Vahdat Shariatpanahi, Z.; Shahbazi, E. Bosentan for high-risk outpatients with COVID-19 infection: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, N.S.; Molnar, J.; Somberg, J. The Efficacy of Nitric Oxide-Generating Lozenges on Outcome in Newly Diagnosed COVID-19 Patients of African American and Hispanic Origin. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 1035–1040.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avezum, Á.; Oliveira Junior, H.A.; Neves, P.D.M.M.; Alves, L.B.O.; Cavalcanti, A.B.; Rosa, R.G.; Veiga, V.C.; Azevedo, L.C.P.; Zimmermann, S.L.; Silvestre, O.M.; et al. Rivaroxaban to prevent major clinical outcomes in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: The CARE-COALITION VIII randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilg, N.; Chew, K.W.; Giganti, M.J.; Daar, E.S.; Wohl, D.A.; Javan, A.C.; Kantor, A.; Moser, C.; Coombs, R.W.; Neytman, G.; et al. ACTIV-2/A5401 Study Team. One Week of Oral Camostat Versus Placebo in Nonhospitalized Adults with Mild-to-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, G.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Hsia, J.; Goldin, M.; Towner, W.J.; Go, A.S.; Bull, T.M.; Weng, S.; Lipardi, C.; Barnathan, E.S.; et al. Rivaroxaban for Prevention of Thrombotic Events, Hospitalization, and Death in Outpatients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2023, 147, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.E.; Hedlin, H.; Duong, S.; Lu, D.; Lee, J.; Bunning, B.; Elkarra, N.; Pinsky, B.A.; Heffernan, E.; Springman, E.; et al. Evaluation of Acebilustat, a Selective Inhibitor of Leukotriene B4 Biosynthesis, for Treatment of Outpatients with Mild-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, D.; Legacy, M.; Conte, E.; Keates, C.; Psihogios, A.; Ramsay, T.; Fergusson, D.A.; Kanji, S.; Simmons, J.G.; Wilson, K. Dietary supplements to reduce symptom severity and duration in people with SARS-CoV-2: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, D.R.; Lindsell, C.J.; Stewart, T.G.; Hernandez, A.F.; Collins, S.; McCarthy, M.W.; Jayaweera, D.; Gentile, N.; Castro, M.; Sulkowski, M.; et al. ACTIV-6 Study Group and Investigators. Inhaled Fluticasone Furoate for Outpatient Treatment of COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaraaty, M.; Bahrami, M.; Azimi, S.A.; Hashem-Dabaghian, F.; Saberi, S.; Abbas Zaidi, S.M.; Sahebkar, A.; Enayati, A. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) syrup as an adjunct to standard care in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: An open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2023, 13, 400–411. [Google Scholar]

- Barco, S.; Virdone, S.; Götschi, A.; Ageno, W.; Arcelus, J.I.; Bingisser, R.; Colucci, G.; Cools, F.; Duerschmied, D.; Gibbs, H.; et al. Enoxaparin for symptomatic COVID-19 managed in the ambulatory setting: An individual patient level analysis of the OVID and ETHIC trials. Thromb. Res. 2023, 230, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiersen, A.M.; Mattar, C.; Bender Ignacio, R.A.; Boulware, D.R.; Lee, T.C.; Hess, R.; Lankowski, A.J.; McDonald, E.G.; Miller, J.P.; Powderly, W.G.; et al. The STOP COVID 2 Study: Fluvoxamine vs Placebo for Outpatients with Symptomatic COVID-19, a Fully Remote Randomized Controlled Trial. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.E.; Sarkis, E.; Acloque, J.; Free, A.; Gonzalez-Rojas, Y.; Hussain, R.; Juarez, E.; Moya, J.; Parikh, N.; Inman, D.; et al. Intramuscular vs Intravenous SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Sotrovimab for Treatment of COVID-19 (COMET-TAIL): A Randomized Noninferiority Clinical Trial. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffito, M.; Dolan, E.; Singh, K.; Holmes, W.; Wildum, S.; Horga, A.; Pietropaolo, K.; Zhou, X.J.; Clinch, B.; Collinson, N.; et al. A Phase 2 Randomized Trial Evaluating the Antiviral Activity and Safety of the Direct-Acting Antiviral Bemnifosbuvir in Ambulatory Patients with Mild or Moderate COVID-19 (MOONSONG Study). Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0007723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]