Abstract

Dental caries is a major global health issue associated with biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans). Conventional antimicrobials often fail to eliminate biofilms due to their structural resistance, highlighting the need for new strategies. This study investigated the antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of protamine peptides (PPs), which are cell-penetrating antimicrobial peptides derived from salmon protamine, alone and in combination with antimicrobial agents. Antimicrobial susceptibility was evaluated using alamarBlue® and colony count assays, while biofilm formation was analyzed using crystal violet staining, confocal microscopy, and extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) quantification. PP exhibited moderate antibacterial activity but strongly suppressed EPS accumulation and biofilm development, leading to a flattened biofilm structure. Cotreatment with ε-poly-L-lysine (PL) significantly enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm effects compared with either agent alone, whereas this effect was not observed with other cationic polymers. Fluorescence imaging revealed that PL promoted the intracellular localization of PP without increasing membrane damage, indicating a cooperative mechanism by which PL enhances membrane permeability and PP targets intracellular sites. These findings demonstrate that combining a cell-penetrating peptide with a membrane-active agent is a novel approach to overcome bacterial tolerance. The PP–PL combination effectively suppressed S. mutans growth and biofilm formation through dual action on membranes and EPS metabolism, offering a promising basis for the development of peptide-based preventive agents and biofilm-resistant dental materials.

1. Introduction

Dental caries remains one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide, affecting individuals across all age groups and imposing a substantial burden on public health systems [1]. The disease results from a complex interplay between host factors, dietary habits, and the oral microbiota, ultimately leading to demineralization of dental hard tissues. Among the diverse microorganisms inhabiting the oral cavity, Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is the principal etiological agent of dental caries [2]. This Gram-positive facultative anaerobe metabolizes dietary polysaccharides to establish biofilms on tooth surfaces and produces organic acids that demineralize enamel and dentin [3]. Biofilm formation not only facilitates acid retention and localized demineralization but also markedly enhances bacterial tolerance to antimicrobial agents, contributing to persistent and recurrent infections.

Monotherapy with conventional antimicrobials remains the predominant approach for treating dental caries; however, numerous bacterial strains exhibiting antimicrobial resistance have been reported [4]. In this context, the present study focused on the application of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and combination therapies as potential strategies against drug-resistant bacteria [5,6]. AMPs possess diverse mechanisms of action that are distinct from those of conventional antibiotics and offer the potential to suppress the emergence of new resistant strains [7,8]. Moreover, combining agents with distinct mechanisms of action exerts synergistic effects against resistant bacteria, thereby enhancing antimicrobial efficacy [9]. Such combination therapies often permit the use of lower drug doses than those in monotherapies, thereby reducing treatment-associated adverse effects.

In this study, we focused on protamine peptides (PPs), which are AMPs derived from salmon milt protamine through enzymatic hydrolysis with thermolysin [10]. Our previous studies demonstrated that protamine may exhibit a dual mechanism of action depending on the treatment concentration [11,12]. Treatment with high protamine concentrations destabilizes the cell membrane, whereas treatment at the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) allows the peptide to penetrate bacterial cells without disrupting the bacterial membrane. Once internalized, protamine inhibits translation and suppresses bacterial growth. In contrast, PP is a cationic peptide containing sequences characteristic of cell-penetrating peptides that exhibits potent antimicrobial activity against S. mutans and the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (C. albicans). Our preliminary studies demonstrated that combined application of protamine and PP enhanced the intracellular uptake of protamine by S. mutans. However, the detailed antibacterial mechanisms and antibiofilm properties of PP against S. mutans have not yet been elucidated. Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of PP against S. mutans under single-agent treatment. In addition, considering that the combination of antimicrobial agents with distinct modes of action may produce synergistic effects, a second objective was to examine changes in antibacterial activity when PP was used in combination with other antimicrobial agents, including ε-poly-L-lysine (PL), poly-L-arginine hydrochloride (PA), and poly-L-ornithine hydrochloride (PO), and assess the antibiofilm effects of these combinations. We hypothesized that PP would exhibit potent antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against S. mutans and that its combination with antimicrobial agents possessing different mechanisms of action would lead to synergistic effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms

The Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) strain (NBRC 13955) was obtained from the NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC, Tsukuba, Japan). S. mutans was cultured in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (Shimadzu Diagnostics Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C using an anaerobic jar (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) with AnaeroPack® Kenki (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical). Cultures were stored at −80 °C in medium supplemented with 15% glycerol.

2.2. Antimicrobial Agents

Protamine peptides (PPs, Table 1) was kindly provided by Maruha Nichiro Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). PP was dissolved in ultrapure water and sterilized by autoclaving (121 °C, 20 min). ε-poly-L-lysine (PL) was purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). poly-L-arginine hydrochloride (PA) and poly-L-ornithine hydrochloride (PO) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC (St. Louis, MO, USA). PL, PA, and PO were dissolved in ultrapure water and sterilized by filtration.

Table 1.

Sequences of protamine and protamine peptides (PP) derived from enzymatic digestion.

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The susceptibility of S. mutans to protamine was evaluated by alamarBlue® assay and colony count assays. Antimicrobial agents (20 μL), bacterial suspension (4 × 105 CFU/mL) diluted by BHI medium (10% for planktonic cells and 25% for biofilm), and 20 μL of alamarBlue® solution (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) were added to 96-well plates. After incubation for 20 h at 37 °C, 20 µL of alamarBlue® solution was added to all wells, followed by an additional 4 h of incubation to monitor color change [13]. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were defined as the lowest concentration at which no color change was observed (red indicating growth and blue indicating no growth).

2.4. Evaluation of Membrane Permeability

Cellular localization of protamine was assessed using N-terminal carboxyfluorescein hydrate (FAM)-labeled protamine peptide (FAM-PP), synthesized by SCRUM Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). To evaluate membrane permeability and damage, cells were co-stained with FAM-PP and propidium iodide (PI; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). An overnight culture was adjusted to a cell density of 4 × 107 CFU/mL in BHI medium. FAM-PP was added to the cell suspension and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min at 1/2 MIC and MICs. Subsequently, PI was added and cells were incubated for an additional 15 min. The cells were then centrifuged (5000 rpm, 5 min), the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in PBS. Samples were observed on a glass-bottom dish using confocal laser scanning microscopy (STELLARIS 5, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.5. Evaluation of Biofilm

An overnight culture of cells was adjusted to a density of 2 × 106 CFU/mL in 25% BHI medium supplemented with 1% sucrose. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of antimicrobial agents for 24 h.

2.5.1. Crystal Violet Staining

Crystal violet staining was performed to quantify biofilm biomass after biofilm formation [14]. At 24 h of cultivation, 1.0 mL of 0.1% crystal violet was added to each well and incubated for 15 min. After aspiration of the stain, the biofilms were rinsed with sterile deionized water and air-dried. The bound crystal violet was then solubilized with 33% acetic acid, and the optical density (OD) was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (MULTISKAN FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5.2. LIVE/DEAD Staining

Cells were treated with 1/2 MIC (PP or PL) or 1/4 MIC each (PP + PL co-treatment) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions for 24 h on glass coverslips placed at the bottom of the wells. Following treatment, the coverslips were washed once with PBS to remove planktonic and loosely attached bacteria. Live cells were then stained with the Live/Dead® BacLight™ Bacterial Viability Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 15 min in the dark. Excess dye was removed by washing with PBS, and the coverslips were mounted on glass slides for fluorescence microscopy. Imaging was performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (STELLARIS 5, Leica).

2.5.3. Production of Extracellular Polysaccharides (EPS)

Cells were cultured at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions for 24 h in the dark on glass coverslips placed at the bottom of the wells. To label EPS, 1.0 mM Alexa Fluor 594–dextran conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added during incubation. Antimicrobial agents were applied at concentrations of 1/2 MIC (PP and PL) or 1/4 MIC each for the combined treatment (PP + PL). Following treatment, coverslips were washed once with PBS to remove planktonic and loosely attached bacteria. Live cells were stained with SYTO®9 at 37 °C for 15 min, protected from light. Excess dye was removed by washing with PBS, and the coverslips were mounted on glass slides for fluorescence microscopy. Imaging was conducted using a confocal laser scanning microscope (STELLARIS 5, Leica).

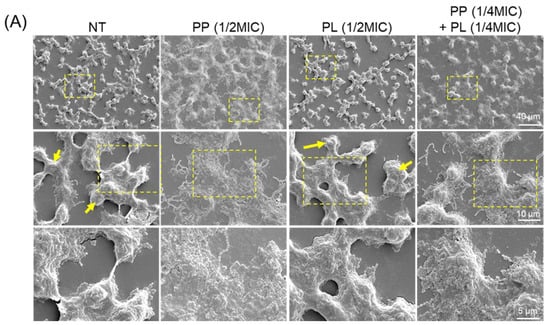

2.6. Morphological Observation by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Cells (2 × 106 CFU/mL) were treated with PP, PL, or PP+PL (1/2 MIC for monotherapy, 1/4 MIC + 1/4 MIC for combination therapy) at 37 °C for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. Following protamine treatment, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 16 h. The fixed cells were then washed with PBS and dehydrated sequentially in 50% ethanol for 3 min, followed by 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99.5% ethanol. Finally, the cells were treated with 100% ethanol for 30 min. Samples were air-dried at 25 °C, mounted on carbon tape attached to a fixed stand, and sputter-coated with gold for 30 s. The specimens were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; VE-9800, KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15.00 kV.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed for determination to determine the mean and standard deviation (S.D.) of the mean. Significant differences were determined using GraphPad Prism software (version 10; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc tests, was used to compare the levels of different experimental groups. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) to AMPs

To evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility of S. mutans to AMPs, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using the alamarBlue® and colony count assays. MIC values are presented in Table 2. Brain heart infusion (BHI) broth was used at a concentration of 10% and 25% for planktonic bacterial cultures and biofilm formation experiments, respectively. Among the tested peptides, PL exhibited the highest antibacterial activity in both media concentrations, whereas PP consistently exhibited the lowest activity.

Table 2.

The MIC values for AMPs against S. mutans.

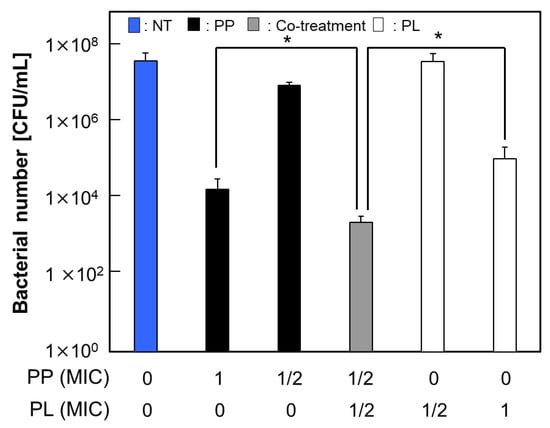

3.2. Synergistic Antimicrobial Activity of Cotreatment with PP and PL

Previous studies have demonstrated that the concomitant application of AMPs with other antimicrobial agents can produce a synergistic interaction, whereby the resultant antimicrobial activity exceeds the additive effects of each treatment administered independently [9]. In the present study, the antibacterial activity of PP in combination with each antimicrobial agent against S. mutans was evaluated using the alamarBlue® and colony count assays. As shown in Figure 1, PP combined with PL exhibited a statistically significant increase in antibacterial activity compared with either treatment alone. In contrast, no significant enhancement in antibacterial activity was observed when PP was combined with antimicrobial agents other than PL (Figure S1). These findings suggest that the combined effects of PP and PL may result from the cooperative or complementary actions of the two agents, which target both intracellular and extracellular sites, thereby inhibiting the normal growth of S. mutans.

Figure 1.

Enhanced antibacterial activity by co-treatment of PP and PL. Viable counts of S. mutans (4 × 105 CFU/mL in 10% BHI medium) after 24 h treatment with PL and/or PP. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of 5 independent biological replicates per group (* p < 0.05).

To examine the specificity of this combined effect, the antibacterial activities of combinations of AMPs, excluding PP, were evaluated. A statistically significant increase in the antibacterial activity was observed when PL was combined with PO (Figure S2). Although the antibacterial properties of PO have not been extensively studied, its high permeability, as a short-chain PO, may confer antibacterial activity [15], suggesting that it possesses properties similar to those of PP.

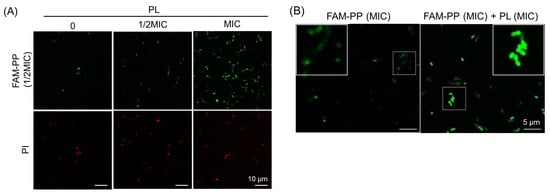

3.3. Promotion of PP Intracellular Localization Through Cotreatment with PL

To further investigate the increase in the antibacterial activity of PP observed following cotreatment with PL, the membrane permeability of S. mutans under combined treatment was assessed. As shown in Table 1, PP is a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) containing the internal sequence “VSRRRRRRGGRRRR.” CPPs can traverse cell membranes [10]. Based on the hypothesis that the increased antibacterial activity observed following drug cotreatment may be attributable to the altered membrane permeability of S. mutans for PP, the intracellular localization of fluorescently labeled PP was examined following cotreatment with PL. For this experiment, fluorescently labeled PP (FAM-PP) was used (Table 1), in which one sequence within PP was conjugated to fluorescein amidite (5/6-FAM). Although the number of membrane-damaged cells remained largely unchanged following cotreatment with FAM-PP and PL, the number of cells exhibiting FAM-PP green fluorescence, localized at or within the cell membrane, increased in a PL concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A). Furthermore, increasing the treatment concentration of FAM-PP in combination with PL to its MIC resulted in a greater number of cells exhibiting green fluorescence localized not only to the cell membrane but also within the bacterial cytoplasm compared with FAM-PP treatment alone (Figure 2B). These findings suggest that PL enhances the membrane permeability of S. mutans for PP.

Figure 2.

Enhancement of internal cellular localization of PP by co-treatment with PL. (A) Increase in PP cell penetration with PL concentration. Fluorescence images of S. mutans in BHI medium after 1 h treatment with FAM-PP (1/2 MIC) alone or in combination with PL (1/2 MIC or MIC). Green fluorescence indicates FAM-PP, and red fluorescence corresponds to PI-positive (membrane-damaged) cells. Scale bars: 10 μm; (B) increase in intracellular localization of PP with co-treatment of PL. Fluorescence images of S. mutans in BHI medium after 1 h treatment with FAM-PP (MIC) alone or in combination with PL. Green fluorescence indicates FAM-PP. The insets show a higher magnification view of the area indicated by the white box, highlighting the peptide distribution. Scale bars: 5 μm.

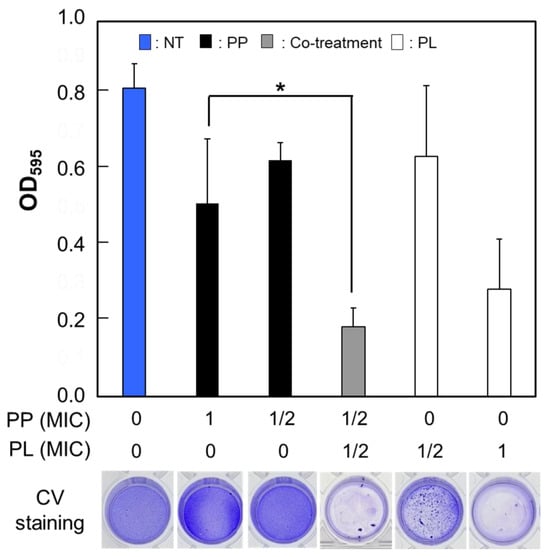

3.4. Enhanced Inhibition of Biofilm Formation Following Cotreatment with PP and PL

S. mutans synthesizes extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) by metabolizing sucrose, thereby contributing to cariogenicity through biofilm formation and acid production [2,3]. Mature biofilms generally exhibit greater resistance to external stimuli such as antimicrobial agents than planktonic bacteria [16,17]. In this study, we investigated the effects of individual antimicrobial agents on S. mutans biofilm formation and evaluated their antibiofilm activity under cotreatment conditions. To promote sufficient biofilm formation by S. mutans within 24 h, the medium concentration was increased from 10% to 25%. Each antimicrobial agent was applied either individually or in combination, and S. mutans was cultured under anaerobic conditions for 24 h. To quantify the total biofilm biomass after incubation, the biofilms were stained with crystal violet, followed by the extraction of the dye, and measurement of its absorbance. Cotreatment with PP and PL at 1/2 MIC produced a significantly greater antibiofilm effect than treatment with PP alone (Figure 3). A similar effect was observed when PL was replaced by PA or PO. However, the MTT assay revealed that cotreatment with PP and other agents did not result in any further inhibition of metabolic activity compared with treatment with PP at its MIC alone (Figure S3). Taken together, the crystal violet and MTT assay results suggested that cotreatment with PP and AMPs enhanced the intrinsic growth-inhibitory and EPS production-suppressing effects of each antimicrobial agent. However, even when concentrations exceeding the MIC were applied to preformed biofilms, no substantial reduction in biomass was observed. This finding suggests that, in established biofilms, the inhibitory effect of antimicrobial treatment is reduced regardless of the drug concentration or whether the agents are used individually or in combination.

Figure 3.

Effective inhibition of biofilm formation by co-treatment with PP and PL. The crystal violet staining results of S. mutans biofilms treated with PP alone or in combination with PL. The amount of biofilm formed by S. mutans after 24 h was measured as optical density at 595 nm following staining with crystal violet. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of 6–8 independent biological replicates per group (* p < 0.05).

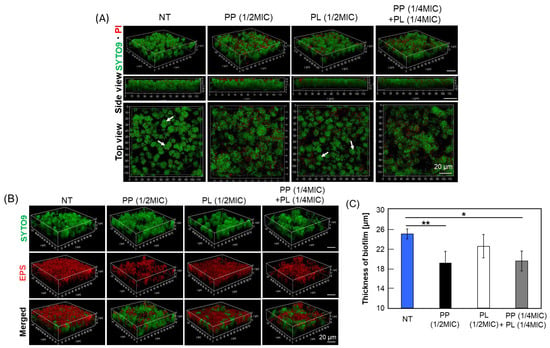

3.5. Effects of PP and PL on Biofilm Structure and EPS Content Under Sub-MIC Conditions

The inhibition of biofilm formation under conditions that do not permit bacterial growth (MIC) can be attributed primarily to a reduction in the number of viable cells rather than to specific interference with biofilm development. To distinguish between these effects, we examined the formation and structural composition of biofilms under subinhibitory conditions (1/2 MIC) that allowed bacterial growth. PP and PL, which showed the highest antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against planktonic cells under cotreatment conditions, were selected for this experiment. Following drug treatment, the composition of live and dead cells within the biofilm was assessed using live/dead staining (Figure 4A). In addition, the distribution of live cells and EPS within the biofilm was examined by visualizing the EPS with an Alexa Fluor 594–dextran conjugate (Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4A, treatment with PP or PL at 1/2 MIC did not markedly alter the number of dead cells within the biofilm, nor were substantial differences observed in the number of live cells. Furthermore, the presence of numerous spherical microcolonies (arrows in Figure 4A) in the untreated and PL-treated groups were observed, whereas the number of microcolonies was reduced in the PP-treated groups. Biofilms typically form microcolonies following initial bacterial attachment and subsequently mature into three-dimensional structures [18,19]. However, in the PP-treated groups, S. mutans biofilms predominantly exhibited a flat morphology. Furthermore, both PP and PL treatments resulted in a marked reduction in the amount of EPS within the biofilm, accompanied by a decrease in overall biofilm thickness (Figure 4C). These findings likely reflect not only the inhibitory effect of PP on EPS production but also the pronounced suppression of bacterial growth attributable to the antimicrobial activity arising from its combined use with PL. Our data suggest that PP inhibits biofilm formation without an accompanying reduction in bacterial cell number.

Figure 4.

Effective inhibition of biofilm formation by co-treatment with PP and PL. S. mutans was cultured in 1% sucrose-supplemented BHI medium for 24 h following treatment with 1/2 MIC of PP, PL alone, or with a combination of 1/4 MIC of each agent. (A) LIVE/DEAD staining of S. mutans in biofilm. Biofilm morphology was examined using CLSM. Green fluorescence corresponds to live cells stained with SYTO9, whereas red fluorescence indicates PI-stained, membrane-damaged cells. “Side view” images represent lateral views of the biofilm structure, and “Top view” images show surface views. Microcolonies are indicated by white arrows. Scale bars: 20 μm; (B) Changes in EPS amount by treatment of PP or PP and PL. Biofilm morphology was analyzed by CLSM. Green fluorescence corresponds to live cells stained with SYTO9, while red fluorescence indicates EPS labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 dextran conjugate. Scale bars: 20 μm; (C) Decrease in biofilm thickness by PP treatment. Biofilm morphology of S. mutans was analyzed by CLSM. For each treatment, biofilm thickness was measured at 10 randomly selected locations within each image field, and the mean value was calculated. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of 3–5 independent biological replicates per group (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

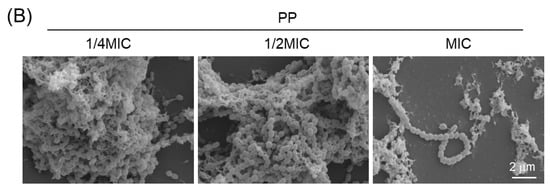

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine morphological changes in biofilms. In the PP-treated groups, including those subjected to cotreatment, a reduction in the EPS layer surrounding the bacterial cells, a decrease in the number of microcolonies, and diminished interconnections between microcolonies were observed (Figure 5A). These findings, which are consistent with the observations shown in Figure 4A, support the possibility that PP treatment suppresses EPS production in S. mutans (Figure 5B). In contrast, no reduction in EPS production by bacterial cells was observed following treatment with PL, PA, or PO (Figure S4). Similarly to the untreated group, numerous microcolonies and interconnections were observed. Collectively, these findings indicate that PP exerts a strong and specific inhibitory effect on S. mutans biofilm formation, suggesting its potential utility as a novel approach for caries prevention.

Figure 5.

Morphological changes in biofilms induced by PP, PL, or their combined treatment. (A) S. mutans was treated with 1/2 MIC of PP or PL, or co-treated with 1/4 MIC of PP and PL, and cultured for 24 h. Biofilm morphology was observed by SEM. The insets show a higher magnification view of the area indicated by the yellow box, highlighting the cell morphology in biofilm. Microcolonies are indicated by yellow arrows. (B) Biofilm morphology at different PP treatment concentrations was observed by SEM. Scale bar: 2 μm.

4. Discussion

This study provides new insights into the antimicrobial activity of PP against S. mutans, an important cariogenic pathogen [2,3]. We confirmed that PP exerted both bactericidal and inhibitory effects on biofilm formation by suppressing EPS accumulation. Although the antibacterial potency of PP alone was moderate compared with that of PL, a remarkable enhanced effect was observed upon cotreatment. PL promoted the intracellular localization of PP without causing additional membrane damage, suggesting that their interactions were cooperative rather than additive. This unique enhanced effect was not reproduced with other cationic agents, such as PA or PO, suggesting a preferential interaction between PP and PL [13]. These findings highlight a novel dual-target antibacterial approach that combines cell-penetrating and membrane-active properties to overcome bacterial defense systems.

This observed enhancement may be attributed to the distinct but complementary mechanisms of PP and PL. PP contains a cell-penetrating motif (“VSRRRRRRGGRRRR”) that facilitates its translocation across bacterial membranes and engagement with intracellular targets [10,13]. Such cell-penetrating antimicrobial peptides (CP-AMPs) interact with nucleic acids or enzymatic components, leading to intracellular dysfunction without extensive membrane disruption [16]. In contrast, PLs exert pleiotropic antibacterial effects via membrane perturbations and interference with intracellular processes [5,7]. When combined, PL enhances membrane permeability, thereby increasing PP uptake and amplifying its intracellular actions. This dual action mechanism is consistent with recent reports describing synergistic AMP combinations targeting multiple bacterial compartments [9,20]. Similar cooperative phenomena between AMPs and antibiotics or other peptides have been documented, suggesting that such enhancement may involve complementary physicochemical and mechanistic interactions rather than simple additive effects [21]. Therefore, the PP–PL combination can be viewed as a model for rational AMP pairing strategies designed to maximize antimicrobial potency while reducing the likelihood of drug resistance development [6,9,22].

Biofilm formation by S. mutans is closely associated with EPS synthesis, which promotes microbial adhesion and structural stability [2,3,16]. Our results demonstrated that PP markedly suppressed EPS accumulation and microcolony formation, leading to flatter and thinner biofilms even under sub-MIC conditions. These findings suggest that PP interferes with specific stages of EPS biosynthesis or secretion rather than merely reducing bacterial viability. Previous studies have shown that certain AMPs such as temporin derivatives inhibit S. mutans biofilm formation by downregulating EPS-related gene expression [23]. Moreover, reviews of AMP–biofilm interactions emphasize that the ability to modulate EPS metabolism is a critical determinant of biofilm control [24,25]. In contrast, PL and other polycations showed a limited influence on EPS, reinforcing the notion that the antibiofilm action of PP is mechanistically distinct. Taken together, these results suggest that PP is a promising preventive agent for early-stage biofilm control, consistent with recent studies on combinatorial AMP strategies for biofilm eradication [20,26].

From a translational perspective, the combination of PP and PL offers a practical and potentially safe approach for oral health care applications. Incorporation of these peptides into restorative resins, orthodontic adhesives, or coatings for dental implants can prevent initial biofilm colonization [4]. Formulations, such as mouth rinses, gels, or varnishes, may further benefit patients prone to recurrent caries or those with compromised oral hygiene. Compared with traditional antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine or cetylpyridinium chloride, they provide broader spectrum efficacy with lower risks of cytotoxicity and drug resistance [5,6,7,8]. Similar synergistic AMP systems have shown promise in preventing biofilm formation on medical devices and wound dressings [20,27]. Therefore, the PP–PL system contributes to a growing paradigm shift from monotherapy to rational AMP combination therapy, in line with recent advances in peptide-based antimicrobial design [7,9,21].

Despite these promising outcomes, this study had several limitations. First, the present study employed monospecies S. mutans biofilms, whereas in vivo oral biofilms consist of polymicrobial communities that interact synergistically or competitively [2,19]. Future studies should explore the effects of PP and PL in multispecies models that better simulate oral ecology [26]. Second, as these experiments were conducted in vitro, in vivo validation is necessary to confirm the peptide stability and bioavailability under salivary conditions [7,10]. Because proteolytic degradation may reduce the efficacy of these agents, stabilization strategies such as peptide cyclization or D-amino acid substitution should be explored [8,21]. Third, although PP inhibited biofilm initiation, mature biofilms exhibited reduced susceptibility, which is consistent with reports that established EPS matrices limit AMP diffusion [24,25]. Combining PP with enzymes or dispersing agents that degrade EPS can enhance the therapeutic potential [20]. Finally, although AMPs are generally less prone to drug resistance, long-term studies are required to monitor their adaptive tolerance mechanisms [6,22].

Further studies should focus on elucidating the intracellular targets of PP in S. mutans, including its potential interactions with enzymes involved in EPS metabolism or stress response pathways [17,18]. Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling could clarify the means by which PP modulates gene expression during biofilm formation [23]. In vivo models of dental caries are crucial for establishing the clinical relevance and safety of the PP–PL combination. Beyond oral applications, this dual-target approach can inform the design of antimicrobial coatings and peptide-based materials for broader biomedical use [20,27].

Collectively, our findings introduce the novel concept of combining a cell-penetrating AMP with a membrane-active counterpart to achieve enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm effects. This strategy may provide a versatile framework for the development of next-generation antimicrobial formulations to combat dental caries and other biofilm-related infections [5,7,9,22].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that PP exerts dual antibacterial activities against S. mutans, including bactericidal effects and suppression of EPS accumulation and biofilm development. Importantly, cotreatment with PL significantly enhanced the intracellular accumulation of PP, leading to synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm effects that were not observed with other cationic agents. These findings introduce the novel concept of combining CPP with a membrane-active peptide to achieve enhanced antimicrobial efficacy. Given the central role of S. mutans biofilms in dental caries pathogenesis, the PP–PL combination represents a promising preventive strategy against cariogenic biofilms. Future studies focusing on multispecies biofilm models, peptide stabilization, and in vivo validation are essential to translate this dual-target approach into practical applications for oral health and potentially for other biofilm-associated infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/micro6010007/s1, Figure S1: Non effect of antibacterial activity by co-treatment of PP and antimicrobial agents; Figure S2: Synergistic effect of antibacterial activity by co-treatment of PL and PO; Figure S3: Changes in Metabolic Activity by Combined Drug Treatment; Figure S4: Morphological observation of biofilms treatment by PA or PO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N. and M.H.; methodology, R.N. and M.H.; validation, R.N., R.T., D.K., M.K. and M.H.; formal analysis, R.N.; investigation, R.N.; resources, M.H.; data curation, R.N., R.T., D.K., M.K. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.N.; writing—review and editing, R.T., D.K., M.K., K.I. and M.H.; visualization, R.N. and M.H.; supervision, R.T., D.K., M.K., K.I. and M.H.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Maruha Nichiro Corporation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

This work was partly funded by Maruha Nichiro Corporation. M.H. and R.N. (Meiji University) received research support from Maruha Nichiro Corporation. Authors R.T., D.K., M.K., and K.I are employees of Maruha Nichiro Corporation. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest. The sponsor provided comments on the manuscript, but the authors retained full control over the study design, data analysis, interpretation, and publication decision.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMP | Antimicrobial peptide |

| PL | ε-poly-L-lysine |

| PA | poly-L-arginine hydrochloride |

| PO | poly-L-ornithine hydrochloride |

| S. mutans | Streptococcus mutans |

References

- Jiang, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Gan, N.; Yang, D. The Oral Microbiome in the Elderly With Dental Caries and Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, J.A.; Palmer, S.R.; Zeng, L.; Wen, Z.T.; Kajfasz, J.K.; Freires, I.A.; Abranches, J.; Brady, L.J. The Biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyściak, W.; Jurczak, A.; Kościelniak, D.; Bystrowska, B.; Skalniak, A. The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulis, E.; Cvitkovic, I.; Pavlovic, N.; Kumric, M.; Rusic, D.; Bozic, J. A Comprehensive Review of Antibiotic Resistance in the Oral Microbiota: Mechanisms, Drivers, and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epand, R.M.; Vogel, H.J. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 1999, 1462, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, B.; Spohn, R.; Lázár, V. Drug combinations targeting antibiotic resistance. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Júnior, N.G.; Souza, C.M.; Buccini, D.F.; Cardoso, M.H.; Franco, O.L. Antimicrobial peptides: Structure, functions and translational applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.; Gross, S.P.; Siryaporn, A. Developing Antimicrobial Synergy With AMPs. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 640981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, J.I.; Cho, T.; Mitarai, M.; Iohara, K.; Hayama, K.; Abe, S.; Tanaka, Y. Antifungal activity in vitro and in vivo of a salmon protamine peptide and its derived cyclic peptide against Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17, fow099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Honda, M. A Novel Control Method of Enterococcus faecalis by Co-Treatment with Protamine and Calcium Hydroxide. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ookubo, M.; Tashiro, Y.; Asano, K.; Kamei, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Honda, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Honda, M. “Rich arginine and strong positive charge” antimicrobial protein protamine: From its action on cell membranes to inhibition of bacterial vital functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2024, 1866, 184323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshikh, M.; Ahmed, S.; Funston, S.; Dunlop, P.; McGaw, M.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of biosurfactants. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, G.A. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 47, e2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, G.; Toyohara, D.; Mori, T.; Muraoka, T. Critical Side Chain Effects of Cell-Penetrating Peptides for Transporting Oligo Peptide Nucleic Acids in Bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 3462–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Ren, S.; Lei, L.; Hu, T. The vicK gene of Streptococcus mutans mediates its cariogenicity via exopolysaccharides metabolism. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J. A GntR Family Transcription Factor in Streptococcus mutans Regulates Biofilm Formation and Expression of Multiple Sugar Transporter Genes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfield, A.H.; Henriques, S.T. Mode-of-Action of Antimicrobial Peptides: Membrane Disruption vs. Intracellular Mechanisms. Front. Med. Technol. 2020, 2, 610997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, M.T.T.; Wibowo, D.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Maisetta, G.; Esin, S.; Batoni, G. Combination Strategies to Enhance the Efficacy of Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri-Araghi, S. Synergistic action of antimicrobial peptides and antibiotics: Current understanding and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1390765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhlongo, J.T.; Waddad, A.Y.; Albericio, F.; de la Torre, B.G. Antimicrobial Peptide Synergies for Fighting Infectious Diseases. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, P.M.; Clarke, M.; Manzo, G.; Hind, C.K.; Clifford, M.; Sutton, J.M.; Lorenz, C.D.; Phoenix, D.A.; Mason, A.J. Temporin B Forms Hetero-Oligomers with Temporin L, Modifies Its Membrane Activity, and Increases the Cooperativity of Its Antibacterial Pharmacodynamic Profile. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batoni, G.; Maisetta, G.; Esin, S. Antimicrobial peptides and their interaction with biofilms of medically relevant bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Santhakumari, S.; Poonguzhali, P.; Geetha, M.; Dyavaiah, M.; Xiangmin, L. Bacterial Biofilm Inhibition: A Focused Review on Recent Therapeutic Strategies for Combating the Biofilm Mediated Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 676458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciandrini, E.; Morroni, G.; Cirioni, O.; Kamysz, W.; Kamysz, E.; Brescini, L.; Baffone, W.; Campana, R. Synergistic combinations of antimicrobial peptides against biofilms of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) on polystyrene and medical devices. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiero, E.; Lombardi, L.; Falanga, A.; Libralato, G.; Guida, M.; Carotenuto, R. Biofilms: Novel Strategies Based on Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.