Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a global health threat, which is becoming more challenging due to the involvement of bacterial virulence mechanisms such as quorum sensing (QS) and biofilm formation. These systems regulate pathogenic traits and shield bacteria from conventional therapies. Phytocompounds offer promising antivirulence strategies by disrupting QS and biofilms without exerting selective pressure. In this study, emodin, a natural anthraquinone, was evaluated for its anti-QS and antibiofilm efficacy. Emodin inhibited violacein production by 63.86% in C. violaceum 12472. In P. aeruginosa PAO1, it suppressed pyocyanin (68.04%), pyoverdin (48.79%), exoprotease (58.55%), elastase (43.13%), alginate (74.12%), and rhamnolipids (56.37%). In S. marcescens MTCC 97, emodin reduced prodigiosin (55.94%), exoprotease (48.80%), motility (83.27%), and cell surface hydrophilicity (41.20%). Biofilm formation was inhibited by over 50% in all three bacteria, highlighting emodin’s potential as a broad-spectrum antibiofilm agent. Molecular docking analyses indicated that emodin exhibited affinity towards QS regulatory proteins CviR, LasR, and SmaR, implying a possible competitive interaction at their ligand-binding sites. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations confirmed these observations by demonstrating structural stability in emodin-bound proteins. The collective insights from in vitro assays and computational studies underscore the potential of emodin in interfering with QS-mediated virulence expression and biofilm development. Such findings support the exploration of non-antibiotic QS inhibitors as therapeutic alternatives for managing bacterial infections and reducing dependence on traditional antimicrobial agents.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has rapidly increased into one of the most concerning threats to global health. Recent estimates show over 1.27 million deaths directly due to drug-resistant bacterial infections in 2019, with more than 4.95 million deaths associated with AMR-related complications annually [1,2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared AMR a top-priority public health emergency, ranking it among the ten greatest health threats facing humanity today [3]. Without urgent intervention, projections warn that AMR could cause 10 million deaths per year by 2050 and trigger a cumulative economic loss exceeding USD 100 trillion, surpassing cancer as a cause of mortality [4,5]. Excessive and improper use of antimicrobials in human medicine, veterinary practice, and agriculture is a primary driver of resistance emergence and spread [6,7]. The clinical misuse and overuse of antibiotics have not only amplified selection pressures on pathogenic bacteria but also indirectly transformed commensal and environmental bacteria into reservoirs of resistance genes. AMR further intensifies the burden of infectious disease by promoting the persistence of chronic and recurrent infections, especially those linked to biofilm-forming pathogens. Thus, AMR represents not only a clinical challenge but also an ecological and evolutionary dilemma that spans local and global boundaries.

Bacteria have the capacity to operate as organized communities, showing collective behaviours via cell-to-cell communication systems known as quorum sensing (QS) [8]. QS enables bacteria to sense their population density and regulate gene expression and phenotypes accordingly by secreting, detecting, and responding to small, diffusible signalling molecules called autoinducers [8,9]. In Gram-negative bacteria, these are often acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), while Gram-positive bacteria use autoinducing peptides (AIPs). This communication governs numerous bacterial activities including virulence, motility, exoenzyme production, stress response, and biofilm formation [10,11].

Biofilms, structured microbial communities encased within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), represent a protective cover that confers increased resistance to antibiotics, disinfectants, host immune responses, and environmental stresses [12,13]. The EPS matrix, comprising polysaccharides, proteins, eDNA, and lipids, acts as a physical barrier, slows the penetration of antimicrobial agents, retains nutrients, and facilitates horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants [14]. Importantly, biofilm-embedded bacteria can be up to 1000-fold less susceptible to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts, making biofilm-associated infections persistent, recurrent, and difficult to manage by conventional therapies [15]. Major human pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and numerous ESKAPE organisms rely heavily on QS-regulated biofilm formation to mediate chronic wound infections, device-related sepsis, respiratory illnesses in cystic fibrosis, and orthopedic implant failure [16]. QS coordinates the transcriptional activation of genes responsible for virulence factors (e.g., proteases, toxins, and adhesins), efflux pumps, and polysaccharide biosynthesis, enhancing bacterial adaptation to both host and environmental pressures [17,18].

In recent years, molecular docking has emerged as a powerful computational tool in the study of QS inhibitors [19]. By simulating the interaction between small molecules and QS regulatory proteins, docking enables the prediction of binding affinities, ligand-binding sites, and potential competitive inhibition at the receptor’s active site. This approach is particularly valuable in identifying new compounds that can disrupt QS signalling without exerting bactericidal pressure, thereby minimizing the risk of resistance development. This study utilized molecular docking to provide possible mechanistic insights into emodin’s ability to interfere with key QS regulators (LasR, CviR, and SmaR).

Emodin (1,3,8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone) is a naturally occurring anthraquinone derivative found in numerous medicinal plants, including Rheum palmatum (rhubarb), Polygonum cuspidatum, and Cassia occidentalis [20]. Extensively used in traditional Chinese medicine, emodin exhibits a remarkable diversity of pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antifibrotic, anticancer, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, antioxidant, and notably, broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects [21]. Notably, emodin has demonstrated promising antibacterial properties, particularly against Gram-positive pathogens such as S. aureus and multidrug-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, as well as several Gram-negative species including E. coli, P. mirabilis, and Klebsiella spp. [20,22]. Beyond antibacterial action, preliminary studies have found emodin to be a QS and biofilm inhibitor [23]. The detailed effect of emodin on biofilm and the QS of Gram-negative bacteria is still unknown.

This study focuses on the influence of emodin on QS-mediated virulence traits exhibited by certain Gram-negative bacterial strains, namely C. violaceum 12472, P. aeruginosa PAO1, and S. marcescens MTCC 97. The selected bacterial strains represent phylogenetically distinct Gram-negative organisms with well-characterized QS systems and pigment-linked virulence markers. C. violaceum utilizes the CviI/CviR system to regulate violacein production, P. aeruginosa employs the LasI/LasR and RhlI/RhlR systems to control pyocyanin, pyoverdin, and biofilm-associated traits, and S. marcescens relies on the SmaI/SmaR system to modulate prodigiosin synthesis and surface hydrophobicity. These bacteria share a common QS mechanism in Gram-negative bacteria using AHLs as signal molecules. Moreover, using different bacteria also allows for a wider evaluation of emodin’s anti-QS efficacy across multiple bacteria with different virulence phenotypes. The potential of emodin in inhibiting and disrupting established biofilms was also examined. Furthermore, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies were carried out to explore the possible mode of QS inhibition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Culture, Growth Conditions, and Chemicals Used

The present investigation employed a range of bacterial strains, namely Chromobacterium violaceum 12472, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and Serratia marcescens MTCC 97. Unless specified otherwise, all cultures were maintained in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, and experimental procedures were carried out under standard laboratory conditions. Emodin (A2491) was procured from Tokyo Chemical Industry Pvt. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), with >97.0% purity (HPLC grade), and used without further modification. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of emodin against each of these strains was assessed using TTC dye in two-fold dilutions ranging from 16 µM to 2048 µM in a 96-well microtiter plate, adhering to established protocols [24]. The MIC of emodin against C. violaceum 12472, P. aeruginosa PAO1, and S. marcescens MTCC 97 was found to be 512 µM, 1024 µM, and 1024 µM, respectively. Subsequent assays related to QS and biofilm formation were performed at concentrations below the MIC (sub-MIC).

2.2. Examination of Violacein in C. violaceum 12472

The process for extracting and quantifying violacein was carried out according to an established method from a previous publication [25]. Briefly, an overnight growth of C. violaceum 12472 culture was performed in LB medium both without and with the addition of emodin at sub-MICs. Once the incubation period was over, a 1 mL sample from the bacterial culture underwent centrifugation to collect the insoluble violacein pigment. The resulting pellet was then mixed with 1 mL of DMSO and vortexed vigorously to ensure the pigment dissolved completely. A subsequent centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min was performed to remove any bacterial cells that remained. Finally, the absorbance of the supernatant, which now contained violacein, was measured at 585 nm.

2.3. Assessment of P. aeruginosa PAO1 Virulence Factors

To boost pyocyanin, the experiment was performed in Pseudomonas broth (PB) as the growth medium. The composition of this medium was 10 g/L potassium sulphate, 1.4 g/L magnesium chloride, and 20 g/L peptone [26]. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 was allowed to grow in this medium for 18 h in the absence and presence of various sub-MICs of emodin. After growth, the bacteria were centrifuged, and 5 mL of culture supernatant was taken. This supernatant underwent liquid–liquid extraction with 3 mL of chloroform. After this, the aqueous layer was carefully discarded. The remaining chloroform fraction, containing the pigment, was treated with 1 mL of 0.2 N HCl. This step results in the formation of a characteristic pink-to-deep-red colour in the aqueous phase. The intensity of this colour was measured by taking its absorbance at 520 nm. Finally, to determine the pyocyanin concentration, the recorded absorbance value was multiplied by a factor of 17.072.

For estimating the pyoverdin, a previously described method was adopted [27]. Briefly, the cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 were grown overnight, one without treatment and the others with various sub-MICs of emodin. These cultures were then centrifuged to obtain a clear supernatant. After that, a small volume (100 µL) of this supernatant was taken and mixed with 900 µL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). The fluorescence of this prepared mixture was then measured using a spectrofluorometer with excitation at 400 nm, and the emission was recorded at 460 nm.

The measurement of elastinolytic activity was measured by taking Elastin Congo Red (ECR) as the main substrate for the enzyme, following the standard method [28]. For this, a 100 µL aliquot of supernatant, collected from both the untreated and the emodin-treated cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1, was combined with 0.9 mL of ECR buffer. This buffer contained 5 g/L ECR and 1 mM calcium chloride prepared in 100 mM Tris buffer. The resulting mixture was then allowed to incubate at 37 °C with constant shaking for 3 h. Once this incubation was over, 1 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 mM and pH 6.0) was added. Following this, the samples were placed on ice for about half an hour to effectively stop the reaction. The mixture was centrifuged to settle any ECR that did not dissolve. Finally, the absorbance of the supernatant obtained was measured at 495 nm.

To check what effect the sub-MICs of emodin had on alginate production, the alginate estimation was carried out according to the standard method [29]. In this assay, P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures were first grown for 18 h without and with sub-MICs of emodin. After growth, 70 µL bacterial suspension was taken and added to 600 µL of boric acid-sulfuric acid reagent, all the while keeping the tube in an ice bath. Following this, 20 µL of carbazole reagent was added into this mixture. The resulting solution was kept for incubation at 55 °C for 30 min. Once the reaction time was completed, the absorbance was taken at 530 nm.

To quantify rhamnolipid, the orcinol method was followed. The procedure involves the addition of 0.3 mL of the supernatant, obtained from untreated and emodin-treated P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures, to 0.6 mL of diethyl ether. After mixing, the two layers were allowed to separate, and the organic layer was carefully collected. The organic phase was left to evaporate at 37 °C. The dry material left behind was then dissolved in 100 µL of deionized water. To this reconstituted sample, 900 µL of the orcinol reagent was added. This reagent was prepared by mixing 0.19% orcinol in a 53% sulfuric acid solution. The entire mixture was then kept at 80 °C for 30 min. After heating, the samples were left to cool down for 15 min. Finally, optical density was measured at a wavelength of 421 nm.

2.4. Examination of Prodigiosin Production in S. marcescens MTCC 97

For the extraction of prodigiosin, S. marcescens MTCC 97 cultures from untreated and emodin-treated groups were taken. The bacterial cells were collected by centrifuging the cultures and supernatant was discarded. To obtain the pigment, the harvested cell pellet was treated with 1 mL of an acidified ethanol solution. This acidified ethanol solution was made by mixing 4 mL of 1 M hydrochloric acid with 96 mL of pure ethanol. After the extraction process, the sample was again centrifuged to remove debris. The prodigiosin present in the solution was quantified by measuring the sample’s absorbance at 534 nm [30].

2.5. Examination of Motility in S. marcescens MTCC 97

To assess swarming motility in S. marcescens MTCC 97, a 5 µL aliquot from an overnight culture was gently placed onto LB agar plates containing 0.5% agar and allowed to air-dry at room temperature. The experiment was conducted both in the absence and presence of different concentrations of emodin. The plates without emodin served as the control. The plates were incubated for 18 h, following which the extent of motility was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the migration zone. Percent inhibition was calculated with respect to the untreated control.

2.6. Determination of Cell Surface Hydrophobicity (CSH)

To assess the CSH, the xylene method was adopted [31]. In short, the method involves adding 1 mL of overnight bacterial culture to 100 µL xylene, along with different sub-MICs of emodin. For the control group, the bacterial cells were mixed only with xylene. This whole mixture was shaken by using vortex for two minutes. The tubes were left at room temperature for the separation of the two layers. Once separated, the absorbance of the aqueous layer was taken at 530 nm. Finally, percentage hydrophobicity was calculated using the standard formula.

2.7. Examination of Exoprotease Activity

To check for proteolytic activity, the method of azocasein degradation was employed [32]. For this assay, cell-free supernatants obtained from the bacterial cultures, both from untreated and emodin-treated, were taken. A small amount of supernatant (0.1 mL) was mixed with 1 mL of 0.3% azocasein solution. This azocasein solution was prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer with a pH of 7.5 containing 0.5 mM of CaCl2. This reaction mixture was kept at 37 °C for 15 min. After this, the reaction was stopped by adding 500 µL of TCA (10%). The sample was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, which settled the precipitated proteins. Finally, the optical density of the supernatant was measured at 400 nm.

2.8. Biofilm Formation Assay

The formation of biofilm was tested in 96-well microtiter plate using crystal violet dye. The overnight cultures of the test bacteria were used to inoculate the wells. Each well contained 150 µL of the growth medium and the bacterial inoculum. The treatments were conducted varying the sub-MICs of emodin. The untreated groups served as the control. The plate was kept for incubation for 24 h. Once the incubation was complete, the media were taken out to remove planktonic cells. The wells gently rinsed three times with sterile buffer solution. After washing, the wells were left to dry for 20 min. To stain the biofilm, 200 µL crystal violet was added to each well and left for another 20 min. The extra unbound stain was then washed with a sterile buffer. Finally, the dye-bound biofilm was dissolved in 90% ethanol solution. The intensity of this pigment was then measured by reading the absorbance at 620 nm on a microplate reader.

2.9. Molecular Docking

To further examine how emodin affects the QS of the tested bacteria, molecular docking was used. For this study, the specific proteins that are known to be involved in QS were selected as the target proteins. The target proteins, CviR from C. violaceum, LasR from P. aeruginosa, and SmaR from S. marcescens, were selected for this study. The 3D structure of emodin [CID: 3220] was downloaded from the PubChem database in SDF format, which was then converted to PDB format using UCSF Chimera software 1.14. The ligand was made flexible with MGL Tools-1.5.6 and the file was saved in PDBQT format. The docking was run using AutoDock Vina, a programme known to be faster and more accurate than the AutoDock4 [33]. The target proteins were sourced from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The structure of SmaR was modelled with MODELLER 10.4. Before docking, these protein structures were prepared by removing water molecules, adding non-polar hydrogen atoms, and applying Kollman charges, which were performed using MGL Tools-1.5.6 [34]. The details for the grid box are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Finally, the prepared receptor files were also saved in the PDBQT format. For the analysis of the interactions of the docked structures, PyMOL 3.1.6.1 and Discovery Studio 2024 were used.

2.10. Molecular Dynamics and Simulation

To understand the behaviour of emodin bound to target proteins, MD simulations were performed. To run the simulations, Gromacs 2018.1 software was used, and it was set up with the amber99sb-ILDN force-field parameters to define the atomic interactions [35,36]. The protein topologies were prepared within Gromacs. However, for the ligand (emodin), the topology was created using the Antechamber module from the AmberTools24 suite, where the AM1-BCC method was applied to compute the atomic charges [37]. Once prepared, the topologies of both the protein and the ligand were combined. Each of these protein–ligand complexes were placed inside a cuboidal box and filled with TIP3P water molecules. To make the system neutral, counter ions were added. Furthermore, sodium chloride was also added to achieve a salt concentration of 150 mM, which is the physiological salt level. To ensure the optimum box size, the gap between the protein/complex and the edges of box was maintained at least at 1.0 nm, which was also required satisfy the periodic boundary conditions (PBCs). The first step in the simulation was energy minimization, which was performed using the steepest descent method. Following this, the system was equilibrated in two phases: first, under the NVT ensemble where the volume was constant and the temperature was maintained at 310 K using the V-rescale thermostat for 500 picoseconds [38]. The second phase was under the NPT ensemble, where both pressure and temperature were held constant at 310 K, using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat for another 500 picoseconds [39]. Once equilibrated, each system was then simulated for 100 nanoseconds, during which 5000 frames of the trajectory were saved. All simulations were conducted in three replicates. Before conducting the analysis, PBC corrections were made. To quantify the interaction energies between emodin and the target proteins, MM-PBSA calculations were performed [40].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Each in vitro experiment was carried out thrice independently. The outcomes have been presented as mean values accompanied by standard deviations. The t-test was employed for p-value calculation. * The p-value falls below 0.05 in comparison with the control group. All MD simulation data are presented as averages with standard deviations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Inhibition of Violacein Pigment in C. violaceum 12472

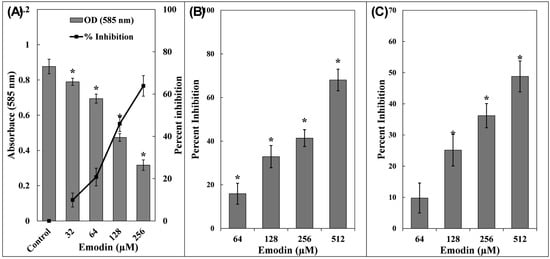

In C. violaceum 12472, the biosynthesis of violacein is controlled via a QS mechanism. The enzyme CviI facilitates the synthesis of acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), which are subsequently recognized by the receptor protein CviR. Upon reaching a threshold density, this interaction triggers the transcription of genes responsible for violacein production [41]. To evaluate the inhibitory impact by emodin on violacein synthesis, spectrophotometric measurements were employed. The absorbance at 585 nm for the untreated bacterial culture was 0.87 ± 0.04. A gradual decline in this pigment’s absorbance was observed with increasing concentrations of emodin, as depicted in Figure 1A. At emodin concentrations of 32, 64, and 128 µM, pigment production dropped by 9.88 ± 3.28%, 20.76 ± 4.17%, and 45.94 ± 3.60%, respectively. Interestingly, the highest sub-MIC (256 µM) resulted in a substantial 63.86 ± 4.86% reduction in violacein pigment production. These observations clearly indicate that emodin disrupts the QS-regulated pathway governing violacein synthesis in C. violaceum 12472.

Figure 1.

(A) Inhibition of violacein production by emodin in C. violaceum 12472. Secondary y-axis represents percent inhibition with respect to control. (B) Inhibition of pyocyanin production by emodin in P. aeruginosa PAO1. (C) Inhibition of pyoverdin production by emodin in P. aeruginosa PAO1. The data are presented as the average of three replicates along with standard deviation. * Indicates p-value < 0.05 with respect to control.

3.2. Examination of P. aeruginosa PAO1 Virulence Factors

Pyocyanin, a blue-green secondary metabolite pigment, is a virulence factor in P. aeruginosa [42]. In the untreated cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1, pyocyanin levels were measured at 7.23 ± 0.53 µg/mL. The addition of emodin led to a concentration-dependent decline in pigment synthesis (Figure 1B). At emodin concentrations of 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM, pyocyanin decreased to 6.08 ± 0.34, 4.85 ± 0.36, 4.24 ± 0.28, and 2.31 ± 0.35 µg/mL, accounting to inhibitions of 15.91 ± 4.80%, 32.90 ± 5.08%, 41.39 ± 3.88%, and 68.04 ± 4.95%, respectively. The role of pyocyanin in the pathogenic behaviour of P. aeruginosa has been extensively documented, especially its interference with host cellular functions [43]. Both pyocyanin and its precursor, phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, are known to hinder the synchronized movement of respiratory cilia and alter the expression of immune-related proteins, these effects are particularly detrimental in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis [44]. Additionally, pyocyanin facilitates immune system evasion by inducing apoptosis in neutrophils and contributes to the establishment and maintenance of biofilms [45]. Its capacity to generate oxidative stress in human endothelial cells is also reported [46].

Pyoverdin, a fluorescent siderophore known for its iron-binding properties, is a virulence-linked metabolite secreted by P. aeruginosa [47]. This compound plays a pivotal role in facilitating infection and contributing to tissue damage. At a low concentration of emodin (64 µM), the reduction in pyoverdin levels was only 9.78 ± 3.23% (statistically insignificant). However, as the emodin dosage increased, a marked decline in pyoverdin secretion was observed, reductions of 25.14 ± 4.06%, 36.19 ± 2.61%, and 48.79 ± 3.54% were recorded at 128, 256, and 512 µM, respectively, when compared to the untreated control group (Figure 1C). Pyoverdin aids the pathogen’s survival by binding to mammalian transferrin, thereby depriving host tissues of essential iron and intensifying the infections [48]. Moreover, it evades recognition by host lipocalin proteins associated with neutrophil gelatinase, which allows P. aeruginosa to establish long-term colonization, especially problematic in individuals suffering from cystic fibrosis [47]. Given these pathogenic attributes, emodin may offer promising effects in attenuating the virulence of P. aeruginosa.

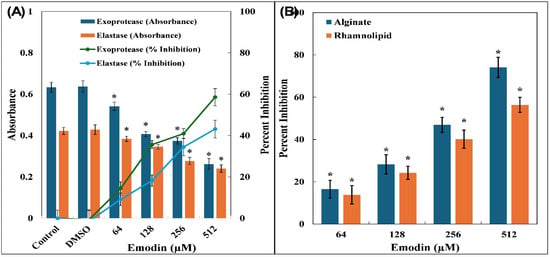

In P. aeruginosa, the synthesis of proteolytic enzymes is governed by QS pathways. As the level of AHLs builds up, it activates the LasR and RhlR receptor systems, which in turn trigger the transcription of several virulence-associated genes, including those responsible for protease production [49]. To evaluate the influence of emodin, an azocasein degradation assay was conducted. The findings revealed a clear dose-dependent suppression of protease activity. Emodin at concentrations of 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM led to the reductions of 14.42 ± 3.20%, 35.65 ± 1.91%, 40.91 ± 2.43%, and 58.55 ± 4.15%, respectively (Figure 2A). These proteases play a crucial role in the pathogenicity of bacterium by breaking down host cellular proteins, thereby aiding in tissue invasion and helping the pathogen evade immune responses [50].

Figure 2.

(A) Inhibition of exoprotease and elastase by emodin in P. aeruginosa PAO1. Secondary y-axis represents percent inhibition with respect to control. (B) Inhibition of alginate and rhamnolipid production by emodin in P. aeruginosa PAO1. The data are presented as average of three replicates along with standard deviation. * Indicates p-value < 0.05 with respect to control.

The influence of emodin on QS-regulated elastase LasB activity was also examined. Supernatant from P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures indicated a notable decline in elastase activity, with reductions of 9.14 ± 3.02%, 18.21 ± 2.72%, 34.46 ± 4.18%, and 43.13 ± 4.26% observed at 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM emodin concentrations, respectively (Figure 2A). P. aeruginosa is well recognized for secreting various hydrolytic enzymes, including elastases, which actively degrade components of the host’s extracellular matrix and interfere with immune system functioning [51]. Given that Las proteins form a core part of the QS regulatory network responsible for virulence factor expression and biofilm formation, the observed inhibition of both protease and elastase activities by emodin strongly points towards its disruptive effect on lasI–lasR signalling.

Alginate forms an essential component of the extracellular polymeric matrix that stabilizes biofilm architecture in P. aeruginosa [52]. When the bacterium was exposed to sub-MICs of emodin, a clear dose-dependent decline in alginate synthesis was observed (Figure 2B). The treatments with 64, 128, and 256 µM of emodin resulted in reductions of 16.51 ± 4.21%, 28.25 ± 4.53%, and 46.89 ± 3.60%, respectively, in alginate levels. Furthermore, at the highest sub-MIC (512 µM), a pronounced inhibitory effect was observed, reducing alginate production by more than 74%.

A comparable trend was noted in the synthesis of rhamnolipids by P. aeruginosa PAO1 following treatment with emodin, as illustrated in Figure 2B. The administration of emodin at concentrations of 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM resulted in a gradual decline in rhamnolipid levels, with reductions of 13.84 ± 4.32%, 24.23 ± 3.13%, 40.12 ± 4.28%, and 56.37 ± 3.53%, respectively. These biosurfactant compounds (rhamnolipids), play a vital role in modulating QS-dependent motility and contribute significantly to biofilm formation during pathogenic invasion [53]. Owing to their amphiphilic nature, rhamnolipids enhance the ability of bacterial cells to traverse surfaces, thereby aiding in the initial stages of biofilm development [54]. Their involvement in surface colonization and the structural integrity of biofilms makes them crucial targets for antivirulence strategies.

3.3. Examination of S. marcescens MTCC 97 Virulence Factors

Prodigiosin is a reddish pigment synthesized by S. marcescens, and its biosynthesis is governed by QS [55]. Observations clearly indicate that emodin exerts a concentration-dependent suppressive effect on prodigiosin (Table 1). The pigment’s production decreased by 16.18 ± 2.80%, 33.12 ± 4.87%, 41.62 ± 4.44%, and 55.94 ± 2.94% when exposed to emodin at concentrations of 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM, respectively. Previous studies have suggested that in certain strains of S. marcescens, the regulatory pathways involved in prodigiosin synthesis may be linked with other cellular traits such as protease activity, flagellar morphology, and hemagglutination ability [56].

Table 1.

Inhibition of virulence factors of S. marcescens MTCC 97 by emodin.

To further assess the antivirulence efficacy of emodin, the exoprotease inhibition in S. marcescens MTCC 97 was checked, using azocasein as the substrate. The findings confirmed that emodin significantly reduced the activity of azocasein-degrading proteases in S. marcescens MTCC 97, and this inhibition was found to be dose-dependent. The treatment with 512 µM emodin led to a nearly 50% reduction in protease secretion, as illustrated in Table 1. Proteases secreted by S. marcescens are known to play a key role in modulating host immune and inflammatory responses, thereby establishing themselves as crucial virulence determinants [57]. Moreover, S. marcescens is reported to synthesize at least four AHLs, namely 3-oxo-C6-HSL, C6-HSL, C7-HSL, and C8-HSL, which are known for regulating the resistance to carbapenem antibiotics, the production of prodigiosin, and several virulence-associated traits such as motility and biofilm development [58].

The influence of emodin on the CSH of S. marcescens MTCC 97 was evaluated, considering that CSH plays a vital role in bacterial adhesion to solid surfaces and in the establishment of biofilms [59]. A marked reduction in CSH was observed upon treatment with emodin, and the suppression followed a dose-dependent trend. In untreated control cells, the percentage hydrophobicity was 67.28 ± 2.60%. However, exposure to emodin at 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM led to a progressive decline in CSH values, recorded at 58.53 ± 3.50%, 51.48 ± 2.01%, 33.30 ± 4.46%, and 26.08 ± 3.94%, respectively, as depicted in Table 1. Since microbial surface hydrophobicity is closely linked to the initial stages of biofilm development, modulating CSH emerges as a promising approach to hinder biofilm formation.

Swimming motility is recognized as a hallmark trait of pathogenic strains of Serratia marcescens, contributing significantly to hospital-acquired infections, particularly those linked to urinary catheters [59]. To assess swarming in S. marcescens MTCC 97, agar plates supplemented with emodin were used. On the control plates lacking emodin, the bacteria swarmed freely, covering the entire plate, as depicted in Supplementary Figure S1. When exposed to 64 and 128 µM of emodin, the swarming zone barely reduced by 4.34 ± 2.08% and 7.02 ± 1.53% (statistically insignificant), but the production of prodigiosin pigment was effectively reduced. At higher doses of 256 and 512 µM, the swarming motility was substantially reduced by 58.19 ± 5.87% and 83.27 ± 4.52%, respectively (Table 1). Motility in bacteria is known to facilitate surface attachment, thereby aiding biofilm formation, a process closely associated with the pathogenesis of urinary tract infections caused by S. marcescens [60].

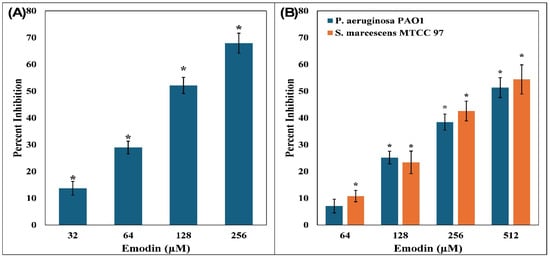

3.4. Inhibition of Biofilm Formation by Emodin

The administration of emodin resulted in a dose-responsive inhibition of biofilm formation in all of the tested bacterial strains. In C. violaceum 12472, emodin concentrations of 32, 64, 128, and 256 µM led to progressive reductions in biofilm by 13.72 ± 2.57%, 28.94 ± 2.37%, 52.13 ± 3.01%, and 67.94 ± 3.71%, respectively, when compared to the control group (Figure 3A). A similar suppressive pattern was evident in P. aeruginosa PAO1, where the treatment of 64, 128, 256, and 512 µM emodin resulted in biofilm inhibition by 7.06 ± 2.38%, 25.20 ± 2.85%, 38.44 ± 2.13%, and 51.31 ± 4.10%, respectively (Figure 3B). For S. marcescens MTCC 97, biofilm was reduced by up to 54.38 ± 5.43% in the presence of 512 µM emodin.

Figure 3.

(A) Inhibition of biofilm formation by emodin in C. violaceum 12472. (B) Inhibition of biofilm formation by emodin in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and S. marcescens MTCC 97. The data are presented as the average of three replicates along with standard deviation. * Indicates p-value < 0.05 with respect to control.

Biofilm formation in is closely associated with the synthesis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), which serve as the structural scaffold for microbial communities [61]. Pathogenicity is largely driven by the ability of bacteria to form robust biofilms, which confer protection against both chemical and physical methods of treatment [62]. This process is also regulated by QS pathways [63]. It is well established that nearly 80% of human infections involve biofilms. This makes emodin a promising candidate for antibiofilm therapy, although further validation using resistant clinical isolates and in vivo models remains necessary.

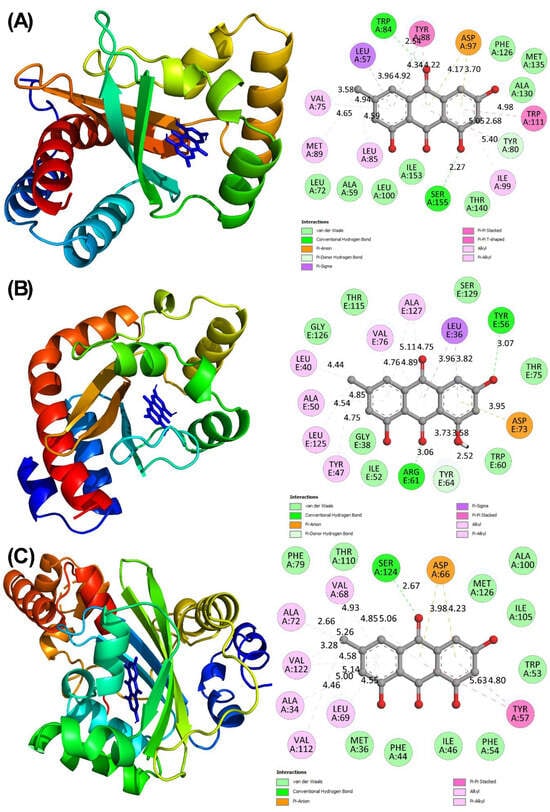

3.5. Interaction of Emodin with Regulatory Proteins of QS Using Molecular Docking

The first step of docking was to validate the procedure. For this, the original ligand was taken out from its crystal structure of the LasR protein. The ligand was then docked to check if the docking method was accurate or not. It was observed that the ligand was docked to its original position inside the LasR’s active site. The docked pose matched with the conformation of the actual crystal’s determined ligand. The docking studies showed that emodin binds with target proteins and binding energies, as enlisted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Binding energies of the proteins with emodin obtained from molecular docking.

In C. violaceum, the production of violacein is governed by QS using the signalling molecule C6-AHL. This autoinducer is recognized by CviR, a transcriptional regulator belonging to the LuxR protein family. CviR is a homodimer, with each subunit comprising 250 amino acids and featuring two domains; one domain is involved in DNA interaction, and the other is dedicated to ligand binding. Structural investigations have revealed that the acyl tail of the native ligand interacts with Asp97 via a hydrogen bond, while the lactone carbonyl group binds with Trp84. Furthermore, the carbonyl oxygen of the ligand forms hydrogen bonds with Ser155 and Tyr80 [64]. Molecular docking has found that emodin fits into the active site of CviR, with a binding energy of −8.9 kcal/mol. Emodin established hydrogen bonds with Trp84, Ser155, and Tyr 80 of CviR (Figure 4A). The complex was also supported by Van der Waals interactions with Phe126, Met135, Ala130, Thr140, Ile153, Leu100, Ala59, and Leu72. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions were noted with residues like Leu85, Met89, Ala75, Leu57, Tyr88, Trp111, and Ile99, and an electrostatic bond was formed between emodin and Asp97 of CviR. C8-AHL and C10-AHL have been identified as antagonists of CviR. It has been suggested previously that small molecules targeting the autoinducer-binding domain could effectively inhibit CviR function [65]. These observations support that emodin may act as a competitive inhibitor by occupying the active site and thereby obstructing native autoinducers from triggering QS-dependent virulent pathways.

Figure 4.

(A) Molecular docked complex of CviR with emodin. (B) Molecular docked complex of LasR with emodin. (C) Molecular docked complex of SmaR with emodin.

In P. aeruginosa, LasR serves as a transcriptional regulator of QS, which is activated by 3-oxo-C12-HSL. Belonging to the LuxR protein family, LasR governs the expression of many virulence-associated genes and plays a crucial role in biofilm development. Molecular docking found that emodin exhibits strong affinity for LasR, with a binding energy of −10.7 kcal/mol. Emodin was found to occupy the same ligand-binding pocket as the native autoinducer. It formed hydrogen bonds with residues of Tyr56, Arg61, and Tyr64, indicating strong polar interactions. Additionally, emodin engaged in hydrophobic contacts with Val76, Ala127, Leu36, Leu40, Ala50, Leu125, and Tyr47. Van der Waals forces were also observed between emodin and residues such as Gly126, Thr115, Ser129, Thr75, Trp60, Ile52, and Gly38, as illustrated in Figure 4B. These molecular interactions suggest that emodin may act as a competitive inhibitor by occupying the ligand-binding domain of LasR, thereby potentially interfering with signal transmission and reducing QS-mediated regulatory response [66].

The interaction between emodin and SmaR exhibited a binding energy of −6.7 kcal/mol, indicating a moderately affinity. A hydrogen bond was observed between emodin and Ser24 of SmaR (Figure 4C). Additionally, binding was stabilized by van der Waals interactions (involving residues Phe79, Thr110, Met126, Ala100, Ile105, Trp53, Phe54, Ile46, Phe44, and Met36), hydrophobic forces (involving residues Val68, Ala72, Val122, Ala34, Val112, Leu69, and Tyr57), and an electrostatic interaction (with Asp66) which collectively contributed to the overall complex formation.

3.6. Molecular Dynamics and Simulation

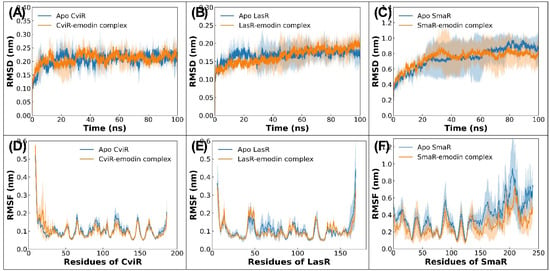

Following molecular docking, MD simulations were carried out for both the apo proteins and ligand-bound protein complexes. To monitor structural deviations throughout the simulation, RMSDs were calculated. These RMSD profiles served as a measure of deviations in trajectory, offering insights into how each molecular system adapted compared to its original structure. As depicted in Figure 5A–C, all systems attained equilibrium within the initial few nanoseconds of simulation [67]. The average RMSDs for apo CviR, CviR-emodin complex, apo LasR, and LasR-emodin complex were 0.206 ± 0.022 nm, 0.209 ± 0.020 nm, 0.166 ± 0.014 nm, and 0.164 ± 0.020 nm, respectively. However, SmaR took slightly longer (~40 ns), which may be due to its larger structure compared to the other two proteins. The average RMSD for the apo SmaR and SmaR–emodin complex were found as 0.746 ± 0.136 nm and 0.746 ± 0.099 nm, respectively. These figures suggest that emodin binding did not have any major structural perturbations, and hence, the proteins maintained their original conformations after the complexion of emodin.

Figure 5.

(A) RMSD of backbone atoms of apo CviR and CviR–emodin complex. (B) RMSD of backbone atoms of apo LasR and LasR–emodin complex. (C) RMSD of backbone atoms of apo SmaR and SmaR–emodin complex. (D) RMSF of alpha carbon atoms of residues of CviR in absence or presence of emodin. (E) RMSF of alpha carbon atoms of residues of LasR in absence or presence of emodin. (F) RMSF of alpha carbon atoms of residues of SmaR in absence or presence of emodin.

To examine residue-level flexibility, RMSF analysis was performed on Cα (alpha carbon) atoms, with the results presented in Figure 5D–F. Most residues of CviR and LasR displayed RMSF values below 0.20 nm, indicating that the protein remained largely stable with only minor fluctuations. Notably, some peaks in RMSF data were observed, loop and coil regions, these regions of protein are typically known for their dynamic nature in aqueous environments [68]. Interestingly, the RMSF profiles of emodin-bound proteins were nearly the same as those of their apo counterparts, implying that emodin binding did not markedly influence backbone mobility. For example, the average RMSF for unbound CviR was 0.107 ± 0.050 nm, which marginally reduced to 0.104 ± 0.055 nm upon binding with emodin. Such minor shifts in RMSF highlight that emodin binding had a negligible effect on CviR and LasR fluctuations. On the contrary, the RMSF in SmaR was relatively higher. The average RMSFs of all residues of SmaR in the absence and presence of emodin were found to be 0.385 ± 0.172 nm and 0.280 ± 0.116 nm, respectively.

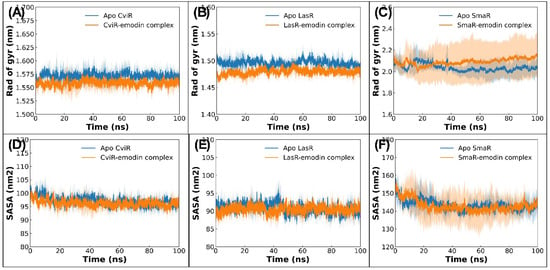

To gain deeper insights into the structural integrity of both the native (apo) proteins and their emodin-bound proteins, the radius of gyration (Rg) and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) were computed. The Rg serves as a reliable measure of protein compactness during MD simulations [69]. Generally, globular proteins, due to their tightly packed architecture, exhibit minimal fluctuations in Rg, whereas proteins with flexible or disordered regions tend to show greater variability. As illustrated in Figure 6A–C, the Rg trajectories for all systems, including apo forms and ligand-bound complexes, remained consistently stable throughout the simulation period. This stability indicates that the overall compactness of the protein structures was well maintained under simulated physiological conditions [70]. For instance, the apo form of CviR recorded an average Rg of 1.571 ± 0.005 nm, which showed only slight shifts to 1.558 ± 0.005 nm upon interaction with emodin. Similarly, the average Rg for apo LasR and the LasR–emodin complex were 1.495 ± 0.005 nm and 1.479 ± 0.005 nm, respectively. Such minor changes suggest that the presence of emodin with target proteins did not compromise the protein’s structural compactness. Similar trends were observed for SmaR, where binding with emodin led to negligible and statistically insignificant alterations in Rg.

Figure 6.

(A) Radius of gyration of backbone atoms of apo CviR and CviR–emodin complex. (B) Radius of gyration of backbone atoms of apo LasR and LasR–emodin complex. (C) Radius of gyration of backbone atoms of apo SmaR and SmaR–emodin complex. (D) Solvent-accessible surface area of apo CviR and CviR–emodin complex. (E) Solvent-accessible surface area of apo LasR and LasR–emodin complex. (F) Solvent-accessible surface area of apo SmaR and SmaR–emodin complex.

SASA values were also computed over the course of the simulation, as depicted in Figure 6D–F. SASA offers a perspective on the degree of surface exposure, which is indicative of conformational shifts following ligand engagement. The findings revealed only marginal differences between apo and complexed states. For example, CviR in its unbound form exhibited an average SASA of 97.047 ± 1.567 nm2, which minutely changed to 96.259 ± 1.238 nm2 upon binding with emodin. LasR followed a similar pattern, with SASA values of 90.791 ± 1.330 nm2 in its apo state and 143.285 ± 2.667 nm2 when complexed with emodin. These subtle shifts in SASA suggest that emodin interaction had a minimal influence on the proteins’ surface exposure. Taken together, the consistent Rg and SASA profiles across all of the systems strongly support that both apo and ligand-bound proteins retained their conformational stability under the simulated physiological conditions [71].

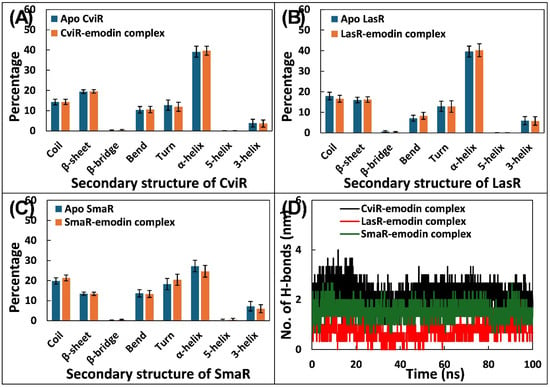

In order to evaluate how emodin influences the structural integrity of the target proteins, a calculation of the secondary structure was performed. The results, illustrated in Figure 7A–C, revealed that the interaction with emodin did not bring any significant changes in the secondary structure of the target QS proteins. Taking CviR as an example, the apo protein displayed an average percentage of coils, β-sheets, bends, turns, and total helices as 14.280, 19.409, 10.431, 12.761, and 43.001, respectively. These percentages remained nearly unchanged upon binding with emodin. A comparable trend was noted in the case of LasR, where the apo protein exhibited secondary structure elements of coils, β-sheets, bends, turns, and total helices as 17.919, 15.956%, 7.122, 12.892, and 45.489, respectively. Following complex formation with emodin, the respective percentages shifted only marginally to 16.572%, 16.202%, 8.274%, 12.785%, and 45.952%, indicating that emodin binding does not substantially disturb the native secondary structure of these proteins.

Figure 7.

(A) Average percentage of secondary structure of apo CviR and CviR–emodin complex. (B) Average percentage of secondary structure of apo LasR and LasR–emodin complex. (C) Average percentage of secondary structure of apo SmaR and SmaR–emodin complex. (D) Number of hydrogen bonds formed by emodin with target proteins (CviR, LasR, or SmaR).

To better understand how emodin interacts at the molecular level with its respective target proteins, an assessment of hydrogen bond dynamics was performed. The data of hydrogen bonds is presented in Figure 7D. Among the three tested proteins, emodin exhibited more average hydrogen bonds with CviR, forming an average of 2.150 ± 0.410 hydrogen bonds. Similarly, the average number of hydrogen bonds formed by emodin with SmaR was 1.535 ± 0.283. In contrast, emodin showed comparatively lower hydrogen bonding, averaging only 0.727 ± 0.330 hydrogen bonds with LasR. Overall, the findings underscore the nature of hydrogen bond interactions between emodin and its targets, implying that the ligand maintained reasonably stable and consistent binding profiles with the target proteins.

To explore the thermodynamic aspects of how emodin binds with the target proteins, MM-PBSA computations were carried out. This calculation used 100 frames taken from each MD trajectory, spanning 50 ns to 100 ns. The interaction between a protein and ligand is largely governed by a range of non-covalent forces, including electrostatic attractions, hydrophobic effects, Van der Waals interactions, and hydrogen bonding, which together influence the binding strength and structural stability of the complex. The energy profiles derived from MM-PBSA analysis are presented in Table 3. Among the different energetic contributors, Van der Waals interactions emerged as the most significant factor driving the binding of emodin to target proteins. Electrostatic forces also fairly contribute to the overall binding. On the other hand, SASA energies played only a minor role across all complexes. Notably, polar solvation energy consistently showed positive values, indicating an energetically unfavourable contribution. The computed total binding free energies for emodin with CviR, LasR, and SmaR were −20.781 ± 0.737, −21.992 ± 0.910, and −21.893 ± 0.408 kcal/mol, respectively.

Table 3.

Various components of binding for the complexation of emodin with CviR, LasR, and SmaR obtained from MM-PBSA calculations.

Furthermore, MM-PBSA also was employed to estimate the individual residue-wise energy contributions in the proteins, as detailed in Table 4. In case of CviR’s binding to emodin, Tyr88 (−1.922 ± 0.053 kcal/mol) emerged as the most significant contributor to binding energy, followed by Ile99 (−1.306 ± 0.025 kcal/mol), Leu100 (−1.219 ± 0.033 kcal/mol), Trp111 (−1.181 ± 0.031 kcal/mol), Leu57 (−1.176 ± 0.025 kcal/mol), Leu72 (−0.768 ± 0.020 kcal/mol), Met135 (−0.733 ± 0.029 kcal/mol), Ile153 (−0.546 ± 0.021 kcal/mol), Leu85 (−0.526 ± 0.036 kcal/mol), Phe126 (−0.523 ± 0.012 kcal/mol), Val75 (−0.390 ± 0.017 kcal/mol), and Ala59 (−0.364 ± 0.012 kcal/mol). A similar observation was found for LasR, where Val76 (−1.720 ± 0.034 kcal/mol) was found to exert the highest energetic influence, followed by Ile52 (−1.195 ± 0.040 kcal/mol), Leu40 (−1.132 ± 0.027 kcal/mol), Ala127 (−1.007 ± 0.037 kcal/mol), Tyr47 (−0.777 ± 0.057 kcal/mol), Leu36 (−0.697 ± 0.030 kcal/mol), Tyr64 (−0.598 ± 0.031 kcal/mol), Leu39 (−0.538 ± 0.022 kcal/mol), Gly38 (−0.527 ± 0.034 kcal/mol), Ala70 (−0.451 ± 0.019 kcal/mol), Ala50 (−0.386 ± 0.020 kcal/mol), and Phe37 (−0.334 ± 0.017 kcal/mol). These residues play a central role in anchoring the ligands within the binding pocket.

Table 4.

Manor energy contributors in CviR, LasR, or SmaR for the interaction with emodin obtained from MM-PBSA calculations.

4. Conclusions

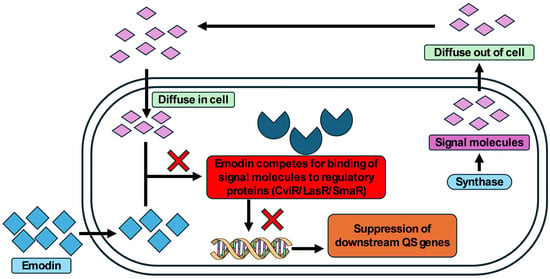

The findings from this investigation establish emodin as a promising phytocompound with notable antiquorum sensing and antibiofilm activity against several Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Emodin effectively reduced the production of key virulence factors such as violacein in C. violaceum; pyocyanin, pyoverdin, elastase, exoprotease, alginate, and rhamnolipids in P. aeruginosa; and prodigiosin, exoprotease, and surface hydrophilicity in S. marcescens. In addition, biofilm formation was significantly reduced across all of the tested strains. Molecular docking and simulation studies further supported its interaction with QS regulators like CviR, LasR, and SmaR. The data indicates that emodin may compete with QS signal molecules of Gram-negative bacteria for the binding of QS regulators (CviR/LasR/SmaR) and inhibit downstream genes expression (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of possible mode of QS inhibition by emodin in Gram-negative bacteria.

5. Future Directions

While emodin demonstrates promising anti-QS and antibiofilm activity against multiple Gram-negative bacteria, further exploration of its translational potential is needed. Several issues, including pharmacokinetics, cytotoxicity, and solubility, etc., must be addressed before clinical application. Future studies may focus on structural optimization of emodin derivatives, targeted delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticle encapsulation), emodin’s synergy with existing antibiotics, and in vivo validation using infection models. Overall, emodin is a potential candidate as an antivirulent agent, but its clinical translation requires multidisciplinary efforts in further research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/micro5040056/s1, Figure S1: Inhibition of swarming motility in S. marcescens MTCC 97 by emodin; Table S1: Details grid size and grid centre of the proteins used in molecular docking study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available with corresponding author and can be obtained on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, S.; Chauhan, A.; Ranjan, A.; Mathkor, D.M.; Haque, S.; Ramniwas, S.; Tuli, H.S.; Jindal, T.; Yadav, V. Emerging Challenges in Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Pathogenic Microorganisms, Novel Antibiotics, and Their Impact on Sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1403168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, S. Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance and Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1172–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaprasad, V.H.; Nayak, V.; Kumar, S. World Health Organisation’s Bacterial Pathogen Priority List (BPPL) 2017 and BPPL 2024 to Combat Global Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis: ‘Challenges and Opportunities’. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.K.; Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 80, 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Darlington, O.; Miller, R.; Gordon, J.; McEwan, P.; Ohashi, T.; Taie, A.; Yuasa, A. Estimating the Economic and Clinical Value of Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance to Three Gram-Negative Pathogens in Japan. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 2021, 8, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, C.A.; Dominey-Howes, D.; Labbate, M. The Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis: Causes, Consequences, and Management. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahizhchi, E.; Sivakumar, D.; Jayaraman, M. Antimicrobial Resistance: Techniques to Fight AMR in Bacteria—A Review. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga, N.G.; Shaaban, M.I.; El-Metwally, M.M. An Insight on the Powerful of Bacterial Quorum Sensing Inhibition. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, M.; Diggle, S.P.; Greenberg, E.P. Progress in and Promise of Bacterial Quorum Sensing Research. Nature 2017, 551, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, S.T.; Bassler, B.L. Bacterial Quorum Sensing: Its Role in Virulence and Possibilities for Its Control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a012427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abisado, R.G.; Benomar, S.; Klaus, J.R.; Dandekar, A.A.; Chandler, J.R. Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Microbial Community Interactions. mBio 2018, 9, e02331-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høiby, N.; Ciofu, O.; Johansen, H.K.; Song, Z.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Bjarnsholt, T. The Clinical Impact of Bacterial Biofilms. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 3, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding Bacterial Biofilms: From Definition to Treatment Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, A.; Mitterer, F.; Pombo, J.P.; Schild, S. Biofilms by Bacterial Human Pathogens: Clinical Relevance—Development, Composition and Regulation—Therapeutical Strategies. Microb. Cell 2021, 8, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manavathu, E.K.; Vazquez, J.A. The Functional Resistance of Biofilms. In Antimicrobial Drug Resistance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Erkihun, M.; Asmare, Z.; Endalamew, K.; Getie, B.; Kiros, T.; Berhan, A. Medical Scope of Biofilm and Quorum Sensing during Biofilm Formation: Systematic Review. Bacteria 2024, 3, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, V.E.; Gillis, R.J.; Iglewski, B.H. Transcriptome Analysis of Quorum-Sensing Regulation and Virulence Factor Expression in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Vaccine 2004, 22, S15–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, A.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Murali, T.S. Quorum-Sensing Regulation of Virulence Factors in Bacterial Biofilm. Future Microbiol. 2021, 16, 1003–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, K.; Kouidhi, B.; Hosawi, S.B.; Baothman, O.A.S.; Zamzami, M.A.; Altayeb, H.N. Computational Screening of Natural Compounds as Putative Quorum Sensing Inhibitors Targeting Drug Resistance Bacteria: Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stompor-Gorący, M. The Health Benefits of Emodin, a Natural Anthraquinone Derived from Rhubarb—A Summary Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Liu, R. Advances in the Study of Emodin: An Update on Pharmacological Properties and Mechanistic Basis. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Chen, F.; Yang, W.; Yan, T.; Chen, Q. Antibiofilm Efficacy of Emodin Alone or Combined with Ampicillin against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yin, B.; Qian, L.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, S. Screening for Novel Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors to Interfere with the Formation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloff, J. A Sensitive and Quick Microplate Method to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration of Plant Extracts for Bacteria. Planta Medica 1998, 64, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.; Deines, P.; Boenigk, J.; Arndt, H.; Eberl, L.; Kjelleberg, S.; Jurgens, K. Impact of Violacein-Producing Bacteria on Survival and Feeding of Bacterivorous Nanoflagellates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, I.; Al-Thubiani, A.S.; Abulreesh, H.H.; AlHazza, I.M.; Aqil, F. Leaf Extracts of Mangifera indica L. Inhibit Quorum Sensing—Regulated Production of Virulence Factors and Biofilm in Test Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankenbauer, R.; Sriyosachati, S.; Cox, C.D. Effects of Siderophores on the Growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Human Serum and Transferrin. Infect. Immun. 1985, 49, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.; Israel, M.; Landshman, N.; Chechick, A.; Blumberg, S. In Vitro Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Elastase by Metal-Chelating Peptide Derivatives. Infect. Immun. 1982, 38, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopu, V.; Meena, C.K.; Shetty, P.H. Quercetin Influences Quorum Sensing in Food Borne Bacteria: In-Vitro and In-Silico Evidence. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, H.; Crow, M.; Everson, L.; Salmond, G.P.C. Phosphate Availability Regulates Biosynthesis of Two Antibiotics, Prodigiosin and Carbapenem, in Serratia via Both Quorum-Sensing-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 47, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; Gutnick, D.; Rosenberg, E. Adherence of Bacteria to Hydrocarbons: A Simple Method for Measuring Cell-Surface Hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1980, 9, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.; Safrin, M.; Olson, J.C.; Ohman, D.E. Secreted LasA of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Is a Staphylolytic Protease. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 7503–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, P.; Agarwal, L.K.; Gupta, N.; Pal, S. Molecular Recognition Pattern of Cytotoxic Alkaloid Vinblastine with Multiple Targets. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2014, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; van der Spoel, D.; van Drunen, R. GROMACS: A Message-Passing Parallel Molecular Dynamics Implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornak, V.; Abel, R.; Okur, A.; Strockbine, B.; Roitberg, A.; Simmerling, C. Comparison of Multiple Amber Force Fields and Development of Improved Protein Backbone Parameters. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006, 65, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa da Silva, A.W.; Vranken, W.F. ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser InterfacE. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kumar, R.; Lynn, A. G_mmpbsa —A GROMACS Tool for High-Throughput MM-PBSA Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanti, E.; Wahyudi, A.T.; Akhdiya, A.; Rusmana, I. Acyl Homoserine Lactone Lactonase Bacteria Potential as Biocontrol Agent of Soft Rot Infection. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2020, 49, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sarkar, A.; Sandhu, P.; Daware, A.; Das, M.C.; Akhter, Y.; Bhattacharjee, S. Potentiation of Antibiotic against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm: A Study with Plumbagin and Gentamicin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H.; Hassett, D.J.; Lau, G.W. Human Targets of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Pyocyanin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14315–14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fothergill, J.L.; Panagea, S.; Hart, C.A.; Walshaw, M.J.; Pitt, T.L.; Winstanley, C. Widespread Pyocyanin Over-Production among Isolates of a Cystic Fibrosis Epidemic Strain. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, T.; Kutty, S.K.; Tavallaie, R.; Ibugo, A.I.; Panchompoo, J.; Sehar, S.; Aldous, L.; Yeung, A.W.S.; Thomas, S.R.; Kumar, N.; et al. Phenazine Virulence Factor Binding to Extracellular DNA Is Important for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Formation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M. Pyocyanin Induces Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial Cells and Modulates the Glutathione Re-dox Cycle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, M.E.; Bhatnagar, A.; McCarty, N.A.; Zughaier, S.M. Pyoverdine, the Major Siderophore in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Evades NGAL Recognition. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2012, 2012, 843509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.C.; Sandhu, P.; Gupta, P.; Rudrapaul, P.; De, U.C.; Tribedi, P.; Akhter, Y.; Bhattacharjee, S. Attenuation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Formation by Vitexin: A Combinatorial Study with Azithromycin and Gentamicin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Li, X.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Lee, J.-H. Post-Secretional Activation of Protease IV by Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.S.; Iglewski, B.H.P. Aeruginosa Quorum-Sensing Systems and Virulence. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003, 6, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Byun, Y.; Park, H.-D. 6-Gingerol Reduces Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Formation and Virulence via Quorum Sensing Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.; Chakrabarty, A.M. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms: Role of the Alginate Exopolysaccharide. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1995, 15, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T.; Curty, L.K.; Barja, F.; van Delden, C.; Pechère, J.C. Swarming of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Is Dependent on Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Requires Flagella and Pili. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 5990–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’May, C.; Tufenkji, N. The Swarming Motility of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Is Blocked by Cranberry Proanthocyanidins and Other Tannin-Containing Materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3061–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morohoshi, T.; Shiono, T.; Takidouchi, K.; Kato, M.; Kato, N.; Kato, J.; Ikeda, T. Inhibition of Quorum Sensing in Serratia Marcescens AS-1 by Synthetic Analogs of N-Acylhomoserine Lactone. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6339–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goluszko, P.; Nowicki, B.; Goluszko, E.; Nowicki, S.; Kaul, A.; Pham, T. Association of Colony Variation in Serratia Marcescens with the Differential Expression of Protease and Type 1 Fimbriae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 133, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kida, Y.; Inoue, H.; Shimizu, T.; Kuwano, K. Serratia Marcescens Serralysin Induces Inflammatory Responses through Protease-Activated Receptor 2. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.-R.; Lai, H.-C. N-Acylhomoserine Lactone-Dependent Cell-to-Cell Communication and Social Behavior in the Genus Serratia. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 296, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salini, R.; Pandian, S.K. Interference of Quorum Sensing in Urinary Pathogen Serratia Marcescens by Anethum Graveolens. Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, ftv038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Devi, K.R.; Kannappan, A.; Pandian, S.K.; Ravi, A.V. Piper Betle and Its Bioactive Metabolite Phytol Mitigates Quorum Sensing Mediated Virulence Factors and Biofilm of Nosocomial Pathogen Serratia Marcescens In Vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 193, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Park, H.-D. Ginger Extract Inhibits Biofilm Formation by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PA14. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A.; Crocetta, V.; De Nicola, S.; Verginelli, F.; Fiscarelli, E.; Di Bonaventura, G. Cooperative Pathogenicity in Cystic Fibrosis: Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Modulates Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Virulence in Mixed Biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Tan, X.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, S.; Jia, A. RNA-Seq-Based Transcriptome Analysis of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilm Inhibition by Ursolic Acid and Resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Bird, S.; Wang, F.; Palombo, E.A. In Silico Investigation of Lactone and Thiolactone Inhibitors in Bacterial Quorum Sensing Using Molecular Modeling. Int. J. Chem. 2013, 5, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Swem, L.R.; Swem, D.L.; Stauff, D.L.; O’Loughlin, C.T.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Bassler, B.L.; Hughson, F.M. A Strategy for Antagonizing Quorum Sensing. Mol. Cell 2011, 42, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Rybtke, M.T.; Jakobsen, T.H.; Hentzer, M.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Computer-Aided Identification of Recognized Drugs as Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2432–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qais, F.A.; Alomar, S.Y.; Imran, M.A.; Hashmi, M.A. In-Silico Analysis of Phytocompounds of Olea Europaea as Potential Anti-Cancer Agents to Target PKM2 Protein. Molecules 2022, 27, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumaili, M.H.A.; Siddique, F.; Abul Qais, F.; Hashem, H.E.; Chtita, S.; Rani, A.; Uzair, M.; Almzaien, K.A. Analysis and Prediction Pathways of Natural Products and Their Cytotoxicity against HeLa Cell Line Protein Using Docking, Molecular Dynamics and ADMET. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qais, F.A.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, I.; Husain, F.M.; Al-kheraif, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Alam, P. Plumbagin Inhibits Quorum Sensing-Regulated Virulence and Biofilms of Gram-Negative Bacteria: In Vitro and In Silico Investigations. Biofouling 2021, 37, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Ameen, F.; Jahan, I.; Nayeem, S.M.; Tabish, M. A Comprehensive Spectroscopic and Computational Investigation on the Binding of the Anti-Asthmatic Drug Triamcinolone with Serum Albumin. N. J. Chem. 2019, 43, 4137–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-Y.; Mo, G.-Q.; Chen, J.-C.; Zheng, K.-C. Exploration of the Binding Mode between (-)-Zampanolide and Tubulin Using Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).