1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global health threat, with substantial mortality and economic costs [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Biofilms—the surface-adherent microbial communities encased in extracellular matrices—further exacerbate the problem by conferring up to 10–1000-fold tolerance to antibiotics [

5,

6,

7]. This creates a clear need for agents with robust anti-biofilm activity. Engineered antimicrobial nanoparticles (NPs) address these gaps via multi-pronged mechanisms (membrane disruption, oxidative stress, and controlled metal-ion release), which hinder resistance development and improve biofilm penetration [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Among various nanomaterials, copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) have attracted strong interest due to their wide range of potential applications in biomedicine, antibacterial agents, catalysis, and electronics [

13,

14]. Copper (Cu) has long been recognized as a natural disinfectant, capable of killing many types of microorganisms through the release of Cu

2+ ions and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

15]. When miniaturized to the nanoscale, CuNPs exhibit superior antibacterial activity due to their large surface area and better contact with bacteria [

16]. Several studies have demonstrated the potent efficacy of CuNPs, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for

Escherichia coli typically ranging from 50–100 µg/mL, significantly lower than that of bulk copper [

17,

18]. Beyond planktonic bacteria, CuNPs have also shown promise in inhibiting biofilm formation and enhancing the effectiveness of conventional antibiotics [

19,

20,

21]. For instance, Lewis Oscar et al. highlighted the ability of CuNPs to efficiently inhibit

Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms [

20], and Rojas et al. evaluated their antibacterial action on ex vivo multispecies biofilms [

17]. However, a significant limitation in the application of CuNPs is their susceptibility to rapid oxidation and aggregation when exposed to air or water, leading to a loss of activity and reduced stability [

22,

23]. This necessitates the development of efficient synthesis methods that maintain the durability and biosafety of the material, often requiring a stabilizing layer to prevent oxygen penetration and limit agglomeration [

23].

In this context, “green” synthesis methods have emerged as a viable alternative to traditional chemical processes that often employ toxic solvents and demand strict reaction conditions [

24]. The essence of green methods lies in utilizing biological compounds, particularly polyphenols from plants, as both reducing and stabilizing agents [

25,

26]. Polyphenols, rich in aromatic hydroxyl (-OH) groups, can effectively reduce Cu

2+ ions to Cu

0 while simultaneously forming a protective coating for the nascent nanoparticles [

27]. This approach offers several advantages, including reduced production costs, minimized hazardous chemical waste, and improved synthesis efficiency and quality of CuNPs, aligning with sustainable development goals in materials science [

28]. Various plant extracts, such as those from

Fortunella margarita leaves, bilberry waste residues,

Polyalthia longifolia roots, and green walnut husks, have been successfully employed for green synthesis of CuNPs [

29,

30,

31,

32].

Building upon the advantages of green synthesis, the focus shifts to specific natural polyphenols. Among these, catechin—a flavonoid abundant in green tea and various other plants—is widely recognized for its antioxidant and metal-chelating properties, attributed to its high content of phenolic hydroxyl groups [

32]. Studies have shown that catechin can act as both a reducing agent and a stabilizer in the synthesis of metal nanoparticles, facilitating electron donation and binding to metal surfaces [

33]. We selected polycatechin (a pre-polymerized catechin) as both reducer and capping agent because its polymeric architecture confers three key advantages over monomeric catechins and other simple polyphenols: (i) enhanced chemical robustness under alkaline/oxidative synthesis conditions, improving batch-to-batch reproducibility [

34]; (ii) higher effective density of phenolic sites that cooperatively reduce Cu

2+ and chelate the nascent metallic surface, yielding well-controlled cores and a cohesive organic shell [

35]; and (iii) intrinsically stronger bioactivity of the shell, which contributes to synergy with the copper core. Together, these features overcome the instability/aggregation typical of CuNPs and produce a durable core–shell nanocomposite with sustained antimicrobial and anti-biofilm performance. Crucially, adhesion between negatively charged Cu@polycat and the likewise negatively charged bacterial envelope is not electrostatic; it arises from stronger non-covalent forces. The amphipathic polycatechin shell engages hydrophobic interactions with lipid domains and forms multivalent hydrogen bonds with cell-wall constituents (e.g., peptidoglycan/teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria and LPS glycans/phosphates in Gram-negative bacteria). This multi-point anchoring locally perturbs the envelope and facilitates deeper access of the copper core/ions—i.e., a “Trojan-horse” delivery—thereby amplifying bactericidal activity [

13]. This synergy results in a potent and rapid bactericidal effect, with prolonged antibacterial action due to the stable coating. Indeed, polyphenol-stabilized CuNP systems have been reported to completely kill both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as some viruses, within minutes of contact [

36]. Podstawczyk et al. notably demonstrated the size-controlled synthesis of copper nanoparticles using (+)-catechin solution [

37].

Previous studies have highlighted the potential of monomeric catechin but also its limited stability and the need for harsh alkaline conditions (pH ~11) to induce polymerization, compromising structural control and reproducibility. We hypothesized that by employing a pre-synthesized, well-defined, and stable polycatechin polymer as a dual-function agent, we could overcome these limitations. This approach aims to create a core–shell nanosystem (Cu@polycat) where the robust polycatechin shell not only prevents oxidation and aggregation but also acts synergistically with the copper core to enhance antibacterial and anti-biofilm efficacy. The overall process is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1. Therefore, this study reports a facile, one-step green synthesis of Cu@polycat, its comprehensive characterization, and a thorough evaluation of its stability, synergistic bactericidal action, and potent anti-biofilm activity against priority pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, ≥98%), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, average Mw ≈ 10,000), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). (+)-Catechin hydrate (≥98%), the monomer precursor for polycatechin synthesis, was also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Polycatechin (polycat) was synthesized in-house according to a facile acid-catalyzed polymerization protocol adapted from Oliver et al. [

38]. Briefly, (+)-catechin hydrate (250 mg) was dissolved in a mixture of deionized water and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (85:15

v/

v) containing 2 M hydrochloric acid (HCl). The reaction proceeded at 40 °C for 48 h under constant stirring and protection from light. The resulting product was neutralized with NaOH, purified extensively by dialysis (Snakeskin™ dialysis tubing, MWCO 3.5 kDa, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) against DMSO/water mixtures followed by pure water to remove unreacted monomers and salts, and finally lyophilized. This method yields water-soluble catechin oligomers with a number-average molecular weight (M

n) of approximately 2900 g mol

−1 and a dispersity of 1.29, as characterized by size-exclusion chromatography [

39].

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB), Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, and agar were sourced from BD Difco (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). All experiments involving the Biosafety Level-2 organism Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 were performed in a certified BSL-2 microbiology laboratory at the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST), following institutional biosafety SOPs and national biosafety requirements.

For mechanistic studies, the fluorescent probes 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, for ROS), N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine (NPN, for outer membrane permeability), and propidium iodide (PI, for membrane integrity) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was also obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

All other chemicals were of analytical grade or higher and were used without further purification. Deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ·cm) from a Mill-Q water purification system (Merck Millipore) was used in all experiments.

2.2. Methods

Unless otherwise specified, concentrations in antimicrobial and biofilm assays are reported as µg/mL of the total dry mass of the tested material (e.g., Cu@polycatechin, CuSO4·5H2O). Where indicated, elemental copper equivalents (µM) are calculated from the copper atomic weight (63.55 g·mol−1) and the measured/assumed copper mass fraction of the formulation. Analytical-grade CuSO4·5H2O was used to prepare stock solutions in sterile water. Vehicle and pH controls were included in all assays (e.g., DMSO ≤ 0.5% v/v where relevant; NaOH-adjusted solutions were neutralized before use).

2.2.1. Synthesis of Cu@polycat Nanoparticles

Cu@polycat nanoparticles were synthesized via a facile one-pot green reduction method, utilizing polycatechin as both a reducing and capping agent. Briefly, an aqueous solution of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, 10 mM) was mixed with an aqueous solution of polycatechin under vigorous stirring (800 rpm). The concentration of the polycatechin stock solution was expressed in terms of its phenolic hydroxyl group content (20 mM, assuming one phenolic group per catechin unit, Mw = 290 g/mol), yielding a final Cu2+:phenolic molar ratio of 1:2. The pH of the reaction mixture was then adjusted to the optimal value of 11.0 by the dropwise addition of 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h at 60 °C in air, during which the color of the solution changed from pale yellow to a deep reddish-brown, indicating the formation of copper nanoparticles. The resulting colloidal suspension was cooled to room temperature, and the pH was neutralized to ~7.0 using a dilute HCl solution to ensure stability during subsequent processing. The nanoparticles were then purified by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 20 min) and washed three times with deionized water to remove unreacted precursors and salts. The final pellet was redispersed in deionized water and stored at 4 °C protected from light until further use.

For comparative studies, PVP-stabilized copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) were synthesized as a control. In brief, an aqueous solution of CuSO4·5H2O (10 mM) was mixed with an equal volume of 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Mw ≈ 10,000) solution under vigorous stirring. The pH of the mixture was adjusted to 11.0 with 1 M NaOH, and the reaction proceeded at 60 °C for 2 h. The resulting nanoparticles were purified by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 20 min), washed three times with deionized water, and redispersed for subsequent experiments. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of these control CuNPs yielded an average core diameter, comparable to the Cu@polycat cores, thereby ensuring a valid like-for-like comparison.

2.2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Nanoparticles

The reduction of Cu2+ ions and the formation of metallic copper nanoparticles were monitored by tracking the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2600, Kyoto, Japan). Spectra of the colloidal suspensions were recorded in the range of 400 to 800 nm at room temperature, using water as a blank. The morphology, size, and size distribution of the nanoparticle cores were analyzed by TEM (JEOL JEM-2100, Tokyo, Japan) operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. A drop of the diluted nanoparticle suspension was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to air-dry at room temperature. The core size distribution was determined by measuring the diameter of over 100 individual nanoparticles from multiple TEM images using ImageJ software v.1.54.b (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) of the nanoparticles in aqueous suspension were measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), while the Zeta potential (ZP) was determined via laser Doppler micro-electrophoresis. Both measurements were performed at 25 °C using a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Samples were appropriately diluted with deionized water to avoid scattering artifacts, and measurements were performed in triplicate. The crystalline structure and phase composition of the nanoparticle powder were analyzed by XRD using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The data were collected in the 2θ range of 20° to 80° with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 2° per minute. The crystalline phases were identified by matching the diffraction patterns with standards from the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) database. The chemical composition of the organic shell and the interaction between polycatechin and the copper surface were investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Samples (nanoparticle powder or pure polycatechin) were placed directly onto the diamond crystal, and spectra were recorded in the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans per sample. Hydrodynamic diameter (D_h) and ζ-potential were measured by dynamic light scattering and electrophoretic light scattering, respectively (25 °C; backscatter detection 173°; ζ measured in 1 mM KCl). The apparent organic-shell thickness was estimated as (D_h − core diameter_TEM)/2 for descriptive purposes.

2.2.3. Colloidal Stability and Ion Release Studies

Stability was challenged under conditions chosen to reflect relevant physiological/pathophysiological environments: pH 5.5, 7.4, 8.0; 150 mM and 300 mM NaCl; and 10% FBS. Specifically, pH 5.5 mimics mildly acidic microenvironments commonly found in inflamed or infected skin, superficial wound exudates, and phagolysosomal compartments where many pathogens are encountered. pH 7.4 corresponds to the physiological pH of blood and interstitial fluids, whereas pH 8.0 reflects the alkaline shift reported in chronic or biofilm-dominated wounds. Similarly, 150 mM NaCl approximates the ionic strength of physiological saline (~0.9% NaCl) in plasma and extracellular fluids, while 300 mM NaCl represents a hypertonic challenge that mimics concentrated or partially evaporated wound fluids, topical hypertonic saline formulations, or salt-rich microenvironments on the surface of dressings and device coatings. Finally, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) was included to represent a protein-rich biological milieu in which a biomolecular corona rapidly forms on nanoparticles, thereby approximating the behavior of Cu@polycat in biological fluids such as blood, wound exudate, and tissue fluids in vivo. Time-courses were recorded at 0–24–48–72 h (and up to 7 days where noted). For ion-release profiling, samples were incubated at the indicated pH/medium and copper ions quantified from supernatants after ultrafiltration.

The long-term colloidal stability was assessed by monitoring the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of aqueous dispersions (100 µg/mL) of Cu@polycat and CuNPs over a 7-day period at 25 °C using DLS. To challenge the nanoparticles under physiological conditions, they were incubated (100 µg/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C in the following media: (i) buffers at different pH values (acetate buffer, pH 5.5; PBS, pH 7.4; Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0), (ii) PBS (pH 7.4) with increasing ionic strength (0, 150, and 300 mM NaCl), and (iii) RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS). Changes in hydrodynamic size and surface charge were measured post-incubation.

The Cu2+ release profiles of both Cu@polycat and CuNPs were investigated using a dialysis method (MWCO 3.5 kDa) to critically evaluate the controlled-release capability of the polycatechin shell. Nanoparticle suspensions (1 mg Cu equivalent) were dialyzed against 50 mL of release media at three different pH values: acetate buffer (pH 5.5), PBS (pH 7.4), and Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The study was conducted at 37 °C under gentle shaking (50 rpm). At predetermined time intervals, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn from the external medium and replaced with an equal volume of fresh, pre-warmed buffer to maintain sink conditions. The concentration of released Cu2+ was quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The cumulative release percentage was calculated and plotted as a function of time for each pH condition. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.2.4. Determination of Antibacterial Activity

The agar well diffusion assay was performed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [

39]. Briefly, Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA) plates were inoculated with a standardized bacterial suspension adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard (~1.5 × 10

8 CFU/mL). Wells of 6 mm diameter were aseptically punched into the solidified agar. Each well was filled with 100 µL of the respective test agent solution. The following concentrations were tested: CuSO

4 (1024 µg/mL), CuNPs (256 µg/mL for

S. aureus and 512 µg/mL for

E. coli), Polycatechin (2048 µg/mL for

S. aureus and 4096 µg/mL for

E. coli), Cu@polycat (32 µg/mL for

S. aureus and 64 µg/mL for

E. coli), and Ampicillin (2 µg/mL for

S. aureus and 8 µg/mL for

E. coli). Sterile distilled water served as a negative control. MIC/MBC testing followed CLSI microdilution with two-fold serial dilutions. For CuSO

4, CuSO

4·5H

2O stocks were freshly prepared and, where elemental copper equivalents were required, converted using molecular weights. For Cu@polycat and CuNPs, concentrations denote total composite mass (µg/mL); elemental copper equivalents were calculated where indicated. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The antibacterial activity was quantified by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones (including the well diameter) in millimeters (mm). Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) were determined using the broth microdilution method in 96-well microplates. Two-fold serial dilutions of each antimicrobial agent were prepared in Mueller–Hinton Broth (MHB) across the wells (columns 1 to 12), resulting in a final volume of 100 µL per well. Column 12, containing only broth and the inoculum, served as the growth control. Each well was then inoculated with 100 µL of a bacterial suspension standardized to approximately 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth. To determine the MBC, 10 µL from each well showing no visible growth was subcultured onto Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration that resulted in ≥99.9% killing of the initial inoculum (i.e., no growth on the subculture). The MBC/MIC ratio was calculated to determine the nature of the antimicrobial activity (bactericidal if ≤4, bacteriostatic if >4). All tests were performed in three independent replicates.

The bactericidal activity and killing kinetics of the agents were further investigated using a time-kill assay. The MBC value of each agent for the respective bacterial strain was used as the test concentration. A bacterial culture in the logarithmic growth phase was diluted in fresh MHB to a concentration of approximately 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The suspension was incubated at 37 °C under constant shaking (120 rpm) in the presence of the antimicrobial agents at their MBCs. Samples (1 mL) were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h), serially diluted in sterile saline, and plated onto MHA plates for viable cell count determination after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The limit of detection (LoD) for the plating method was 100 CFU/mL (2.0 log10 CFU/mL). Samples with counts below this threshold were recorded as “Not Detected” (ND). The results are expressed as mean log10 CFU/mL ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

2.2.5. Synergy Calculation for the Nanocomposite

The synergistic interaction between the copper core and the polycatechin shell within the Cu@polycat nanocomposite was evaluated by calculating the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index. First, the MICs of the individual components (uncoated CuNPs-PVP and free Polycatechin) and the final nanocomposite (Cu@polycat) were determined for each bacterial strain as described in

Section 2.2.4.

The interaction between the copper core (A) and the polycatechin shell (B) was quantified using the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index:

Here, A = uncoated CuNPs and B = free polycatechin. The ‘in-combination’ amounts were defined as the respective masses of A and B contained within the overall MIC of Cu@polycat, apportioned by a fixed Cu:polycatechin mass ratio of ~55:45 (w/w) derived from synthesis stoichiometry and gravimetric recovery after exhaustive washing. Interpretation: synergy (≤0.5), additive (>0.5–1.0), indifference (>1.0–4.0), antagonism (>4.0).

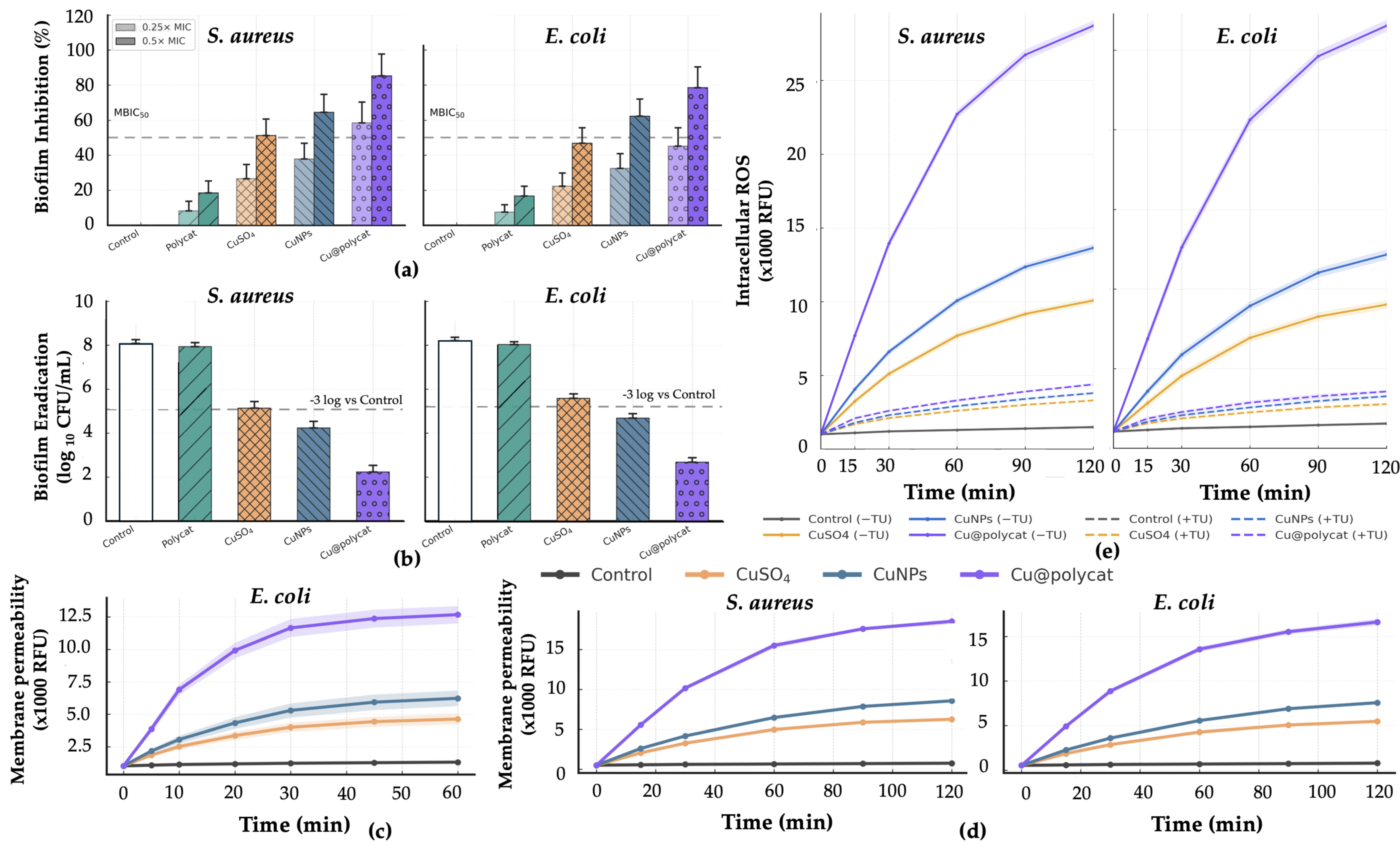

2.2.6. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

The ability of test samples to inhibit biofilm formation was assessed using the crystal violet (CV) staining method as previously described [

40,

41] with slight modifications. Briefly, suspensions of

S. aureus ATCC 6538 or

E. coli ATCC 25922 (approx. 5 × 10

5 CFU/mL in Tryptic Soy Broth supplemented with 1% glucose) were added to sterile 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene plates. The samples (Polycatechin, CuSO

4, CuNPs, and Cu@polycat) were introduced into the wells at sub-inhibitory concentrations of 0.25× and 0.5× their respective MICs. The plates were incubated statically for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the planktonic cells were removed, and the wells were gently washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells. The adhered biofilms were fixed with 99% methanol for 15 min, air-dried, and then stained with 0.1% (

w/

v) crystal violet solution for 20 min. The unbound dye was removed by rinsing the plates with distilled water. The bound CV was solubilized with 33% (

v/

v) glacial acetic acid, and the optical density was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The percentage of biofilm inhibition was calculated using the formula:

The minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC50) was defined as the lowest concentration that resulted in ≥50% inhibition compared to the untreated control. All experiments were performed in triplicate on three independent occasions.

For clinical context, Ampicillin was included at 0.5× MIC (MIC determined by broth microdilution as in

Section 2.2.4) under the same biofilm-forming conditions as Cu@polycat. Each condition used three independent experiments with four technical wells per experiment. Percent inhibition was computed relative to the matched plate control.

2.2.7. Biofilm Eradication Assay

Mature biofilms were established according to a modified protocol [

3]. Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted in fresh TSB + 1% glucose to approx. 1 × 10

6 CFU/mL. Aliquots (200 µL) were dispensed into 96-well plates and incubated statically for 24 h at 37 °C to allow biofilm formation. After formation, the biofilms were gently washed twice with PBS to remove planktonic cells. Fresh medium containing the test samples at a concentration of 4× MIC was added to the pre-formed biofilms. The plates were further incubated for another 24 h at 37 °C. After treatment, the biofilms were washed with PBS and disaggregated by sonication (35 kHz, 5 min) followed by vortexing (2 min) in PBS. The resulting suspensions were serially diluted and plated on Tryptic Soy Agar for viable cell counting after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The results were expressed as log

10 CFU/mL. The bactericidal effect against biofilm was defined as a ≥3-log

10 reduction in CFU/mL compared to the untreated control biofilm.

For 24 h mature biofilms, Ampicillin at 4× MIC was tested in parallel with Cu@polycat 4× MIC and untreated controls for 24 h. Outcomes are expressed as log10 CFU per biofilm; log-reductions vs. control were calculated, with ≥3-log10 regarded as effective eradication. Three independent experiments were performed (four wells/condition).

2.2.8. Outer Membrane Permeability Assay

The outer membrane permeability of

E. coli was determined using the 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN) uptake assay [

42].

E. coli cells were harvested from the mid-logarithmic growth phase, washed, and resuspended in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm. A working solution of NPN was prepared in acetone. To a black 96-well plate, 100 µL of bacterial suspension was mixed with 10 µL of NPN (final concentration 10 µM) and 10 µL of the respective test samples, each at a concentration corresponding to 4× its own MIC against the target strain. The fluorescence was immediately measured kinetically every 5 min for 1 h using a fluorescence microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 350 nm and 420 nm, respectively. To control for potential optical interference, bacteria-free wells containing only nanoparticles and NPN were included. Background fluorescence from these controls was subtracted from experimental signals prior to analysis. An increase in NPN fluorescence intensity indicates the disruption of the outer membrane permeability barrier.

2.2.9. Cytoplasmic Membrane Integrity Assay

The integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane was evaluated using the propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay [

43]. Mid-logarithmic phase cells of

S. aureus or

E. coli were washed and resuspended in PBS to an OD

600 of 0.2. In a black 96-well plate, 100 µL of cell suspension was mixed with 5 µL of PI stock solution (final concentration 10 µg/mL) and 10 µL of the respective test samples, each at a concentration corresponding to 4× its own MIC against the target strain. The fluorescence was measured kinetically every 15 min for 2 h using a microplate reader with excitation/emission wavelengths of 535 nm/617 nm. Propidium iodide fluoresces upon binding to intracellular DNA, which only occurs when the cytoplasmic membrane is compromised. Parallel bacteria-free controls with nanoparticles and PI were run for background correction; these values were subtracted from sample fluorescence to ensure that the reported signal reflects membrane compromise rather than probe–nanoparticle artifacts.

2.2.10. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation Assay

The generation of intracellular ROS was detected using the fluorogenic probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H

2DCFDA) [

44]. Bacterial cells from the mid-logarithmic phase were washed and resuspended in PBS. The cells were then loaded with H

2DCFDA (10 µM) and incubated in the dark for 30 min at 37 °C. Excess probe was removed by centrifugation and washing with PBS. The stained cells were transferred to a black 96-well plate and treated with the test samples at 4× MIC, with or without the ROS scavenger thiourea (50 mM). The fluorescence was measured kinetically every 15–30 min for 2 h at 485 nm excitation and 525 nm emission. An increase in fluorescence indicates the oxidation of H

2DCFDA to the highly fluorescent DCF by intracellular ROS.

2.2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with a minimum of three independent replicates (n ≥ 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0). Normality and homoscedasticity of data were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Brown-Forsythe test, respectively. For comparisons between two groups, an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

A primary challenge in the application of CuNPs is their inherent instability, leading to rapid oxidation and aggregation, which diminishes their antibacterial efficacy [

22,

23,

45]. Our study addresses this limitation through a novel green synthesis approach where polycatechin serves as both a reducing and a capping agent. The successful formation of Cu@polycat nanoparticles was confirmed by the characteristic SPR peak at 580 nm (

Figure 2a), consistent with the formation of metallic copper nanoparticles [

16,

46]. The core–shell structure, with a crystalline copper core of approximately 21.5 nm (

Figure 2b,d) and a surrounding amorphous polycatechin layer, is crucial for the enhanced stability. The resulting nanoparticles exhibited a hydrodynamic diameter of ~45 nm and a highly negative zeta potential of −34 mV (

Figure 2c). This strong negative surface charge provides significant electrostatic repulsion, preventing particle aggregation and ensuring excellent colloidal stability, as evidenced by the minimal changes in size and SPR absorbance over 7 days in aqueous solution and 24 h in physiological media (

Figure 3). This level of stability is a significant improvement over many previously reported green-synthesized CuNPs, which often suffer from poor dispersity and rapid degradation [

14,

23,

24]. For instance, while many plant extract-based syntheses produce effective CuNPs, their long-term stability is often not reported or remains a challenge [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The use of a pre-polymerized, well-defined polycatechin, as opposed to in situ polymerization of catechin monomers, likely contributes to a more uniform and robust coating, overcoming the reproducibility issues associated with some green synthesis methods [

34,

35,

47]. Our approach aligns with the findings of Podstawczyk et al., who demonstrated that catechins can effectively control nanoparticle size, but our use of polycatechin provides an even more durable protective shell [

37,

48].

The most significant finding of this study is the potent synergistic antibacterial activity of Cu@polycat nanoparticles against both Gram-negative (

E. coli) and Gram-positive (

S. aureus) bacteria. The MIC values of Cu@polycat (4 µg/mL for

E. coli and 8 µg/mL for

S. aureus) were 8- to 16-fold lower than those of its precursors, CuNPs and polycatechin alone (

Table 2). This marked increase in potency is confirmed by the FICI value of approximately 0.08, indicating strong synergy. These MIC values are considerably lower than those reported for many other green-synthesized CuNPs, which often fall in the 50–100 µg/mL range [

17,

18].

This synergistic effect is better described as a multi-modal “Trojan-horse” process that does not rely on simple electrostatic attraction. Despite the net negative ζ-potential of Cu@polycat and the anionic bacterial envelope, the polycatechin corona adheres via (i) hydrophobic interactions between its aromatic domains and the lipid bilayer and (ii) multivalent hydrogen-bonding with peptidoglycan/teichoic acids (Gram-positive) or LPS glycans/phosphates (Gram-negative), which together overcome electrostatic repulsion and locally perturb membrane integrity [

35]. This anchoring facilitates close apposition/entry of the copper core; mildly acidic microenvironments then promote shell erosion and Cu

2+ release, while the core catalyzes ROS formation, jointly driving lethal macromolecular damage [

13,

15]. Consistent with this sequence, NPN uptake (outer-membrane permeabilization in Gram-negative bacteria) precedes PI staining (cytoplasmic membrane failure), and time-kill kinetics show a >5-log10 reduction within 6–8 h, an effect not achieved by CuNPs or polycatechin alone at equivalent doses [

13,

36].

Bacterial biofilms remain challenging because of their high tolerance to antibiotics [

6,

7]. Cu@polycat strongly inhibited biofilm formation (>80% at sub-MIC) and, critically, achieved ≥3-log10 viable-count reduction in 24 h mature biofilms under the same exposure conditions where the β-lactam comparator ampicillin was ineffective (no ≥3-log10 reduction). We attribute this to the ~45 nm hydrodynamic size and polycatechin corona that facilitate diffusion through the EPS matrix and multi-target copper-driven damage to embedded/persister cells.

Cu@polycat penetrated the EPS matrix and eradicated mature biofilms, whereas ampicillin, under identical biofilm protocols (inhibition at 0.5× MIC; eradication at 4× MIC), did not produce a ≥3-log10 reduction. These outcomes compare favorably with prior copper nanomaterials and align with state-of-the-art anti-biofilm platforms, supporting translational development for biofilm-associated infections and anti-fouling device applications [

12,

20]. To provide clinical context under identical biofilm protocols, we included ampicillin as a comparator using MIC-normalized dosing (0.5× MIC for biofilm prevention; 4× MIC for eradication; Methods 2.2.6–2.2.7). As shown in

Supplementary Figure S1, ampicillin at 0.5× MIC produced only minimal biofilm prevention (≈5–15%, not significant vs. control), whereas Cu@polycat at the same fractional dose inhibited biofilm formation by ≈75–85% (one-way ANOVA with Tukey,

p < 0.001). For 24 h mature biofilms (

Supplementary Figure S2), ampicillin at 4× MIC did not achieve a ≥3-log

10 reduction in viable counts, while Cu@polycat at 4× MIC delivered ≥4-log

10 eradication (

p < 0.001).

The combination of serum-stable colloids, pH-responsive Cu2+ release and potent anti-biofilm activity positions Cu@polycat for translation as (i) antimicrobial wound dressings (e.g., hydrogel composites delivering sustained local copper at acidic, infected sites) and (ii) anti-fouling coatings for medical devices (catheters, orthopedic hardware).

While this study provides strong in vitro evidence for the potential of Cu@polycat, it has several limitations. The antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities were evaluated against only two representative bacterial strains. Future studies should expand this to a broader range of clinically relevant pathogens, including multidrug-resistant strains. Furthermore, the long-term stability and biocompatibility of Cu@polycat in complex biological systems need to be thoroughly investigated. Although the nanoparticles showed good stability in physiological media for 24 h, their fate and potential toxicity in an in vivo environment are unknown.

Future studies should include cytotoxicity assessments on mammalian cell lines and in vivo toxicity profiling to define a therapeutic index. Formulation optimization for applications like hydrogel wound dressings or implant coatings would enhance translational potential. Long-term resistance development in bacteria should also be evaluated.