Self- and Fick Diffusion Coefficients in Implicit Solvent Simulations: Influence of Local Aggregation Effects and Thermodynamic Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Basic Thermodynamics: Diffusive Motion

2.2. Diffusion Coefficients, Thermodynamic Factors, and KB Theory

2.3. Self-Diffusion Coefficients and Computer Simulations

3. Simulation Details

4. Results

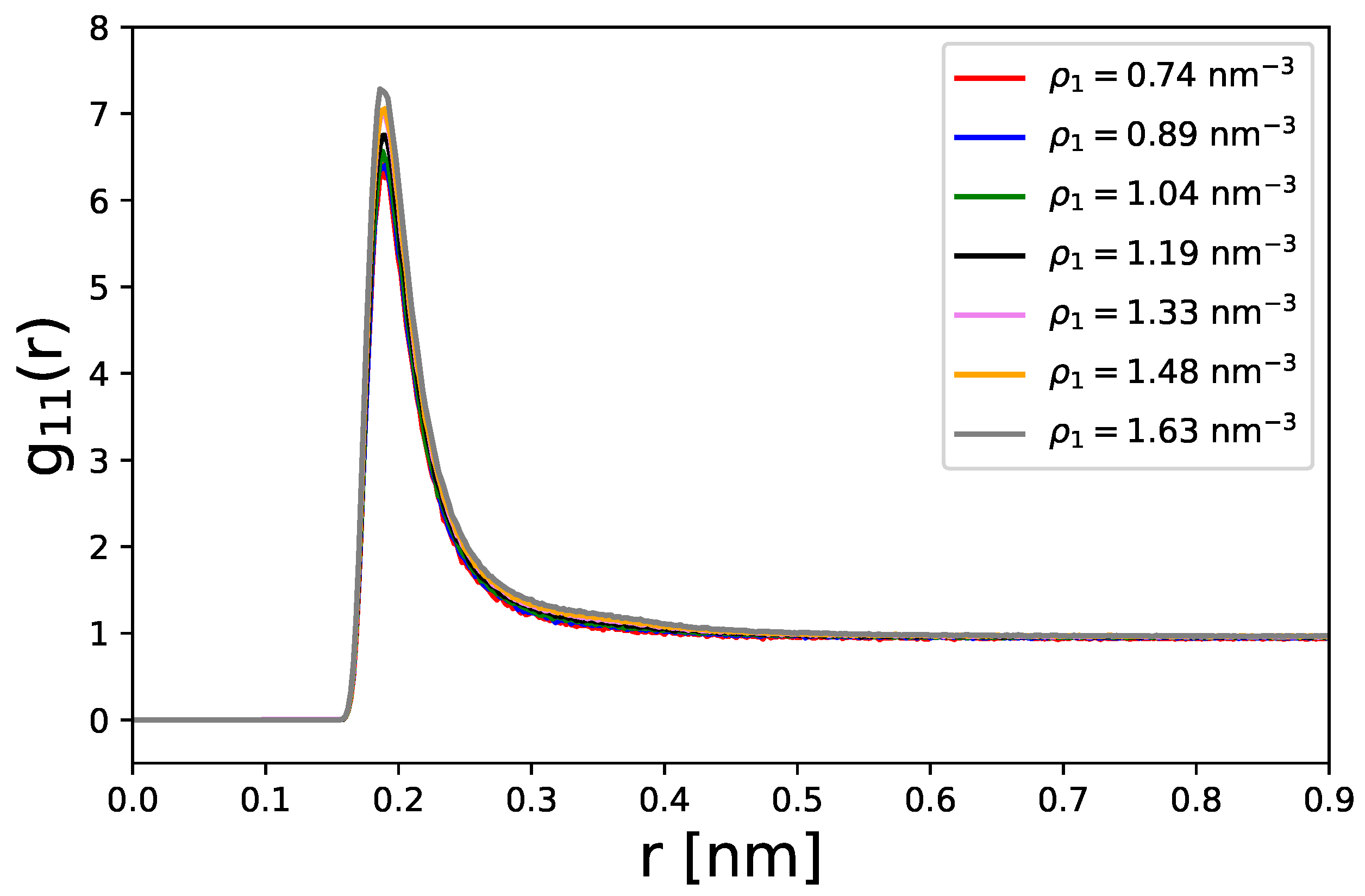

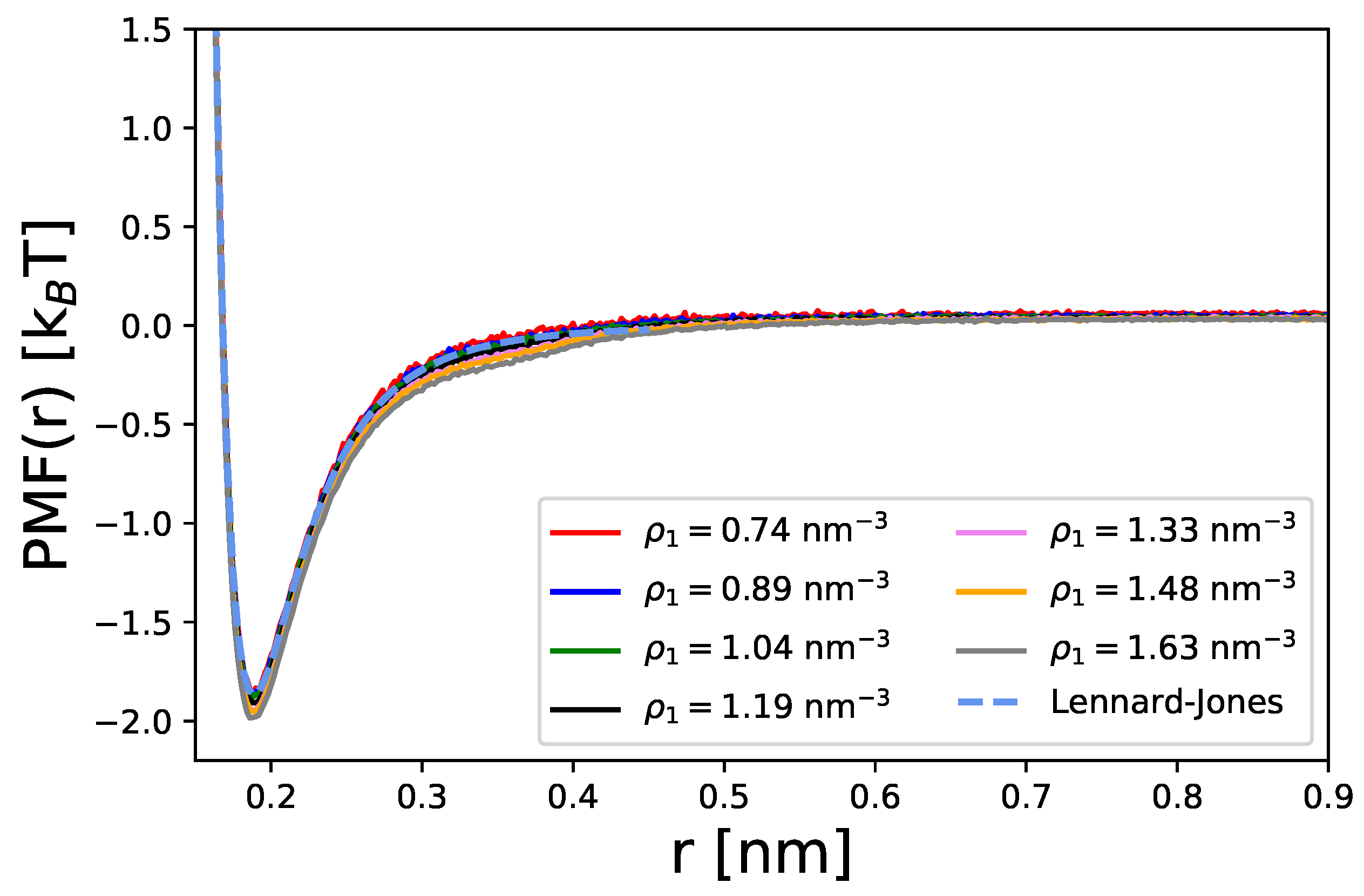

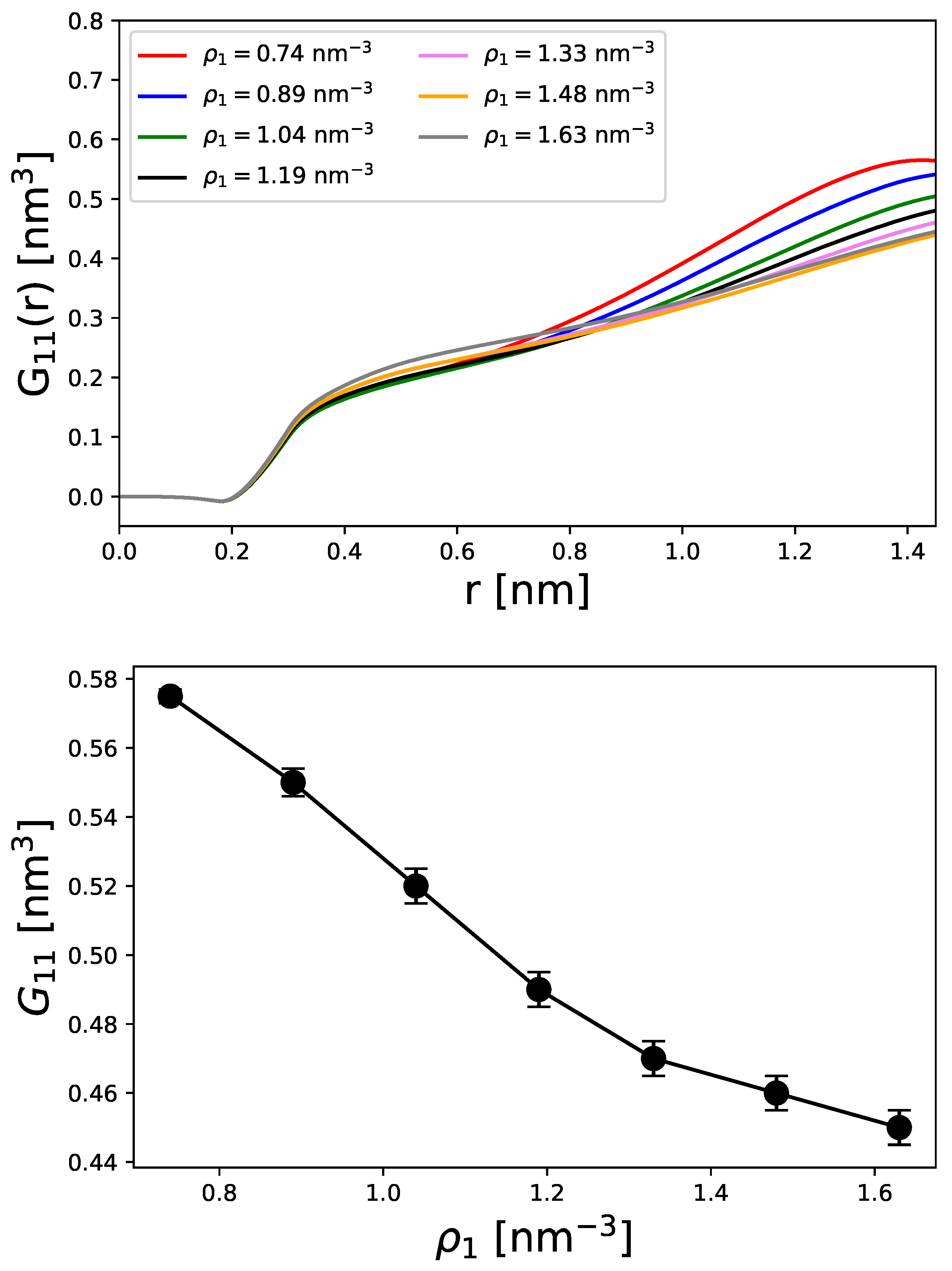

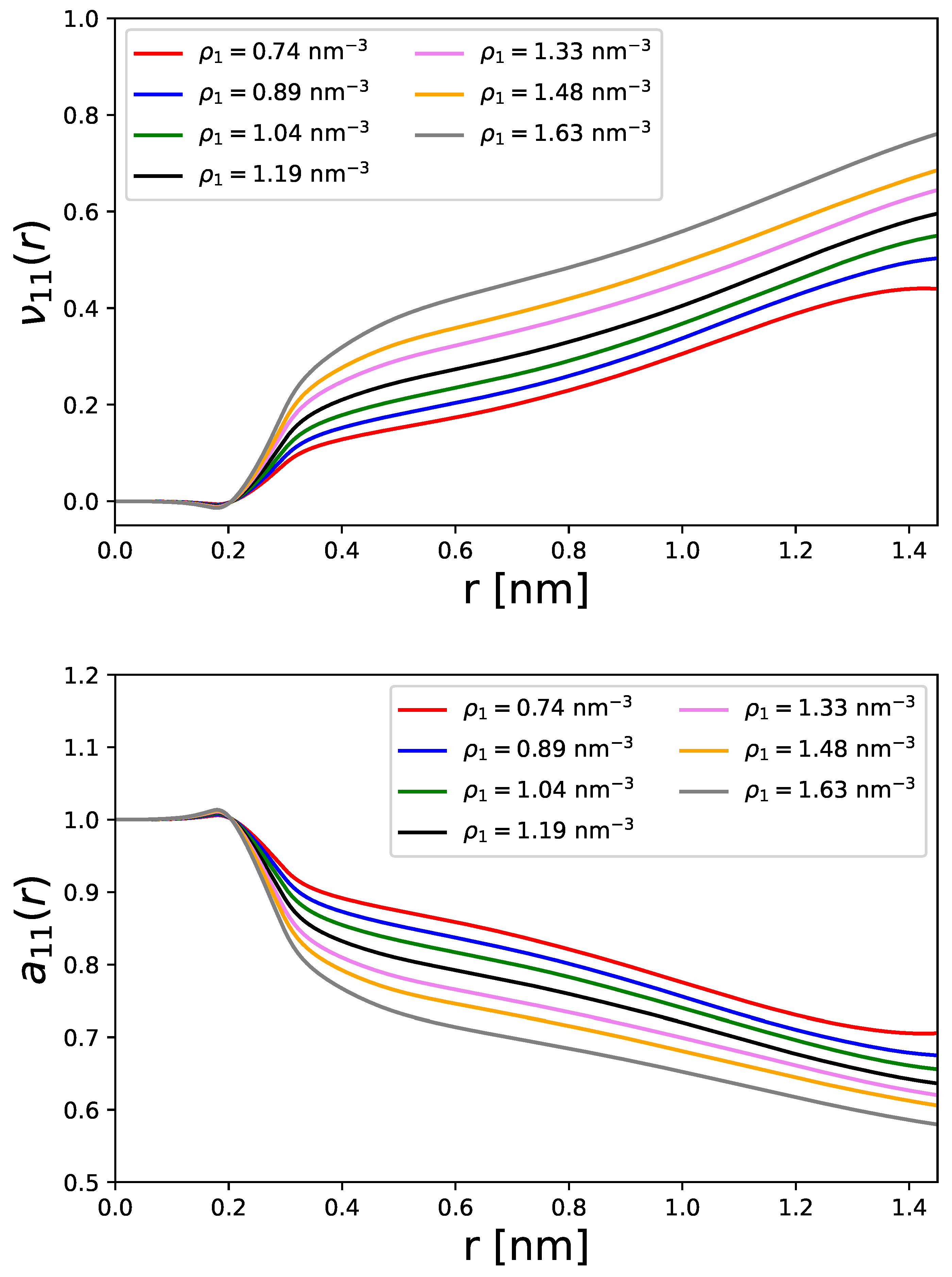

4.1. Structural and Thermodynamic Properties

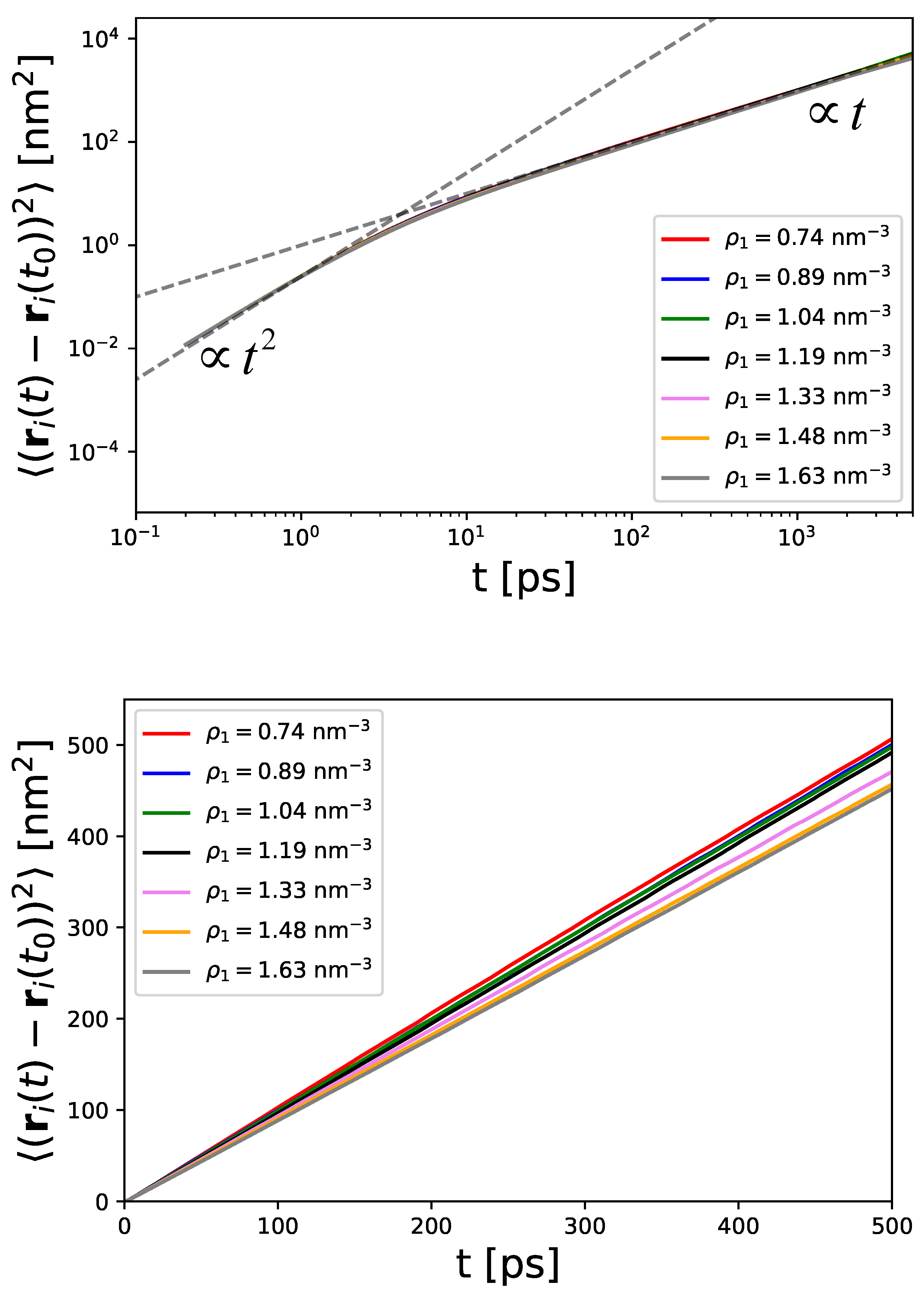

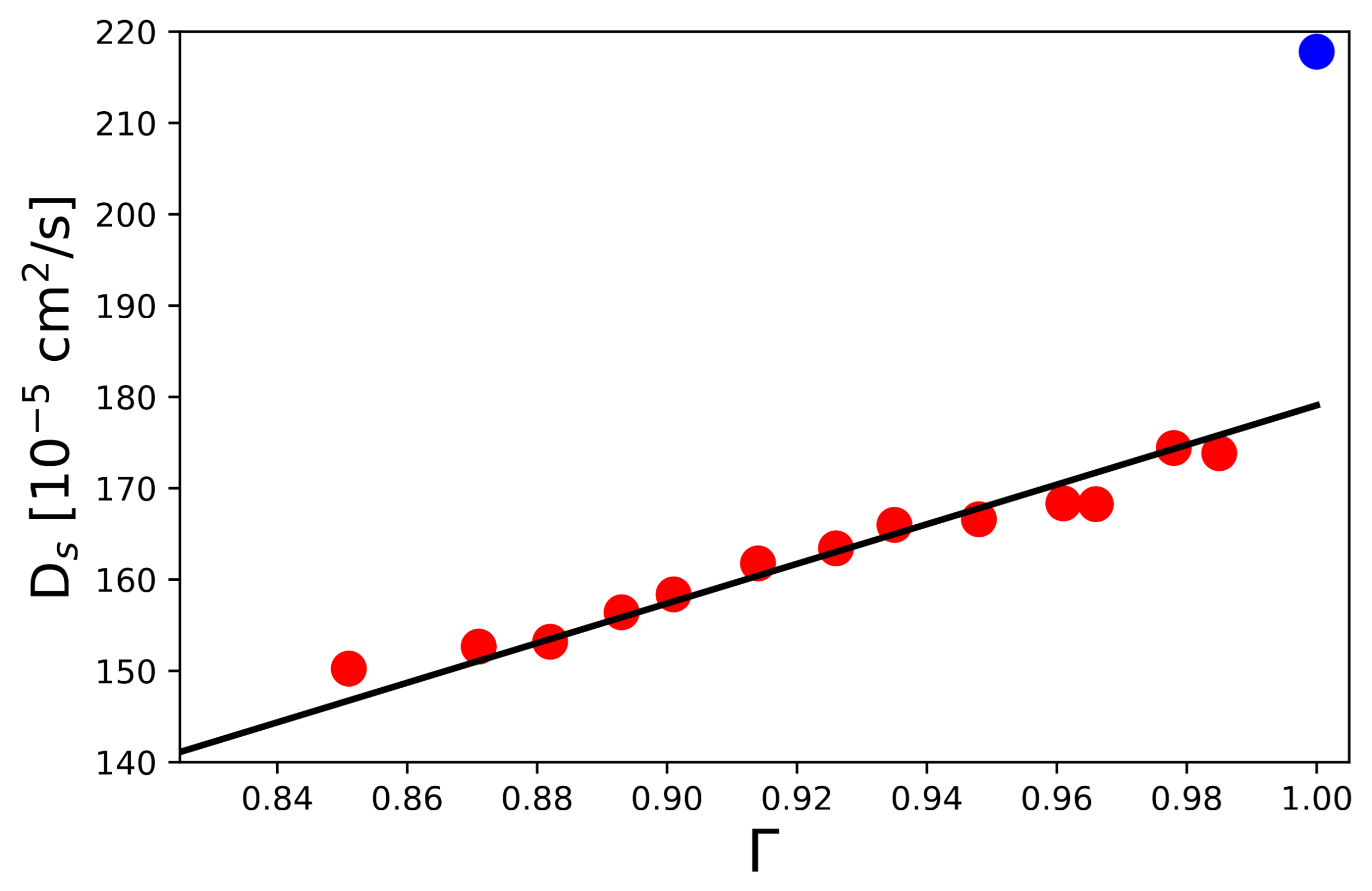

4.2. Dynamic Properties and Diffusive Motion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Seader, J.D.; Henley, E.J.; Roper, D.K. Separation Process Principles; John Wiley & Sons Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wankat, P.C. Separation Process Engineering—Includes Mass Transfer Analysis; Pearson Publishing: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.C. On the dynamical theory of gases. Phil. Transact. Royal Soc. Lond. 1867, 157, 49–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R.B.; Stewart, W.E.; Lightfoot, E.N. Transport Phenomena; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J.; Thomas-Alyea, K.E. Electrochemical Systems; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, S.R.; Mazur, P. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid, J.; Lopez de Haro, M.; Cohen, E. The Enskog theory for multicomponent mixtures. II. Mutual diffusion. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 4509–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlacki, Z.; Easteal, A.; Edge, A.; Woolf, L.; Roksandic, Z. Diffusion coefficients of methanol and water and the mutual diffusion coefficient in methanol-water solutions at 278 and 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 5318–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, H. Mutual diffusion and self-diffusion in the frictional formalism of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. J. Chem. Soc. Farad. Transact. 1985, 81, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trullas, J.; Padró, J. Diffusion in multicomponent liquids: A new set of collective velocity correlation functions and diffusion coefficients. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 3983–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Paduano, L.; Sartorio, R. Multicomponent diffusion in systems containing molecules of different size. 4. Mutual diffusion in the ternary system tetra (ethylene glycol)- di (ethylene glycol)- water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keffer, D.J.; Gao, C.Y.; Edwards, B.J. On the relationship between Fickian diffusivities at the continuum and molecular levels. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 5279–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeldt, S.; Stichlmair, J. Measurement and calculation of multicomponent diffusion coefficients in liquids. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2007, 256, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Van Baten, J. Onsager coefficients for binary mixture diffusion in nanopores. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 3120–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.; Van Baten, J. Unified Maxwell–Stefan description of binary mixture diffusion in micro-and meso-porous materials. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 3159–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeldt, S.; Stichlmair, J. Measurement and prediction of multicomponent diffusion coefficients in four ternary liquid systems. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2010, 290, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Vlugt, T.J.; Bardow, A. Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities in binary mixtures of ionic liquids with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and H2O. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 8506–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggridge, G. Prediction of the mutual diffusivity in binary non-ideal liquid mixtures from the tracer diffusion coefficients. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 71, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Schnell, S.K.; Simon, J.M.; Krüger, P.; Bedeaux, D.; Kjelstrup, S.; Bardow, A.; Vlugt, T.J. Diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations in binary and ternary mixtures. Int. J. Thermophys. 2013, 34, 1169–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parez, S.; Guevara-Carrion, G.; Hasse, H.; Vrabec, J. Mutual diffusion in the ternary mixture of water + methanol + ethanol and its binary subsystems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 3985–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Moggridge, G.D.; D’Agostino, C. A local composition model for the prediction of mutual diffusion coefficients in binary liquid mixtures from tracer diffusion coefficients. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 132, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.; Wolff, L.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Bardow, A. Diffusion in liquids: Experiments, molecular dynamics, and engineering models. In Experimental Thermodynamics Volume X: Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics with Applications; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2015; Volume 10, p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Carrion, G.; Gaponenko, Y.; Janzen, T.; Vrabec, J.; Shevtsova, V. Diffusion in multicomponent liquids: From microscopic to macroscopic scales. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 12193–12210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, T.; Zhang, S.; Mialdun, A.; Guevara-Carrion, G.; Vrabec, J.; He, M.; Shevtsova, V. Mutual diffusion governed by kinetics and thermodynamics in the partially miscible mixture methanol + cyclohexane. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 31856–31873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Krishna, R. Multicomponent Mass Transfer; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap, H.K.; Annapureddy, H.V.; Raineri, F.O.; Margulis, C.J. How is charge transport different in ionic liquids and electrolyte solutions? J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 13212–13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.K.; Fong, K.D.; Persson, K.A.; Lee, A.A. Inferring global dynamics from local structure in liquid electrolytes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.03182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, H.K.; Fong, K.D.; Halat, D.M.; Karouta, C.A.; Celik, H.C.; Reimer, J.A.; McCloskey, B.D. Ion correlation and negative lithium transference in polyelectrolyte solutions. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 6546–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiatek, J.; Heuer, A.; Winter, M. Properties of ion complexes and their impact on charge transport in organic solvent-based electrolyte solutions for lithium batteries: Insights from a theoretical perspective. Batteries 2018, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Y.; Hefter, G. Ion pairing. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4585–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Vegt, N.F.; Haldrup, K.; Roke, S.; Zheng, J.; Lund, M.; Bakker, H.J. Water-mediated ion pairing: Occurrence and relevance. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7626–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiatek, J. Theoretical and computational insight into solvent and specific ion effects for polyelectrolytes: The importance of local molecular interactions. Molecules 2020, 25, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan Krishnamoorthy, A.; Holm, C.; Smiatek, J. Influence of cosolutes on chemical equilibrium: A Kirkwood–Buff theory for ion pair association–dissociation processes in ternary electrolyte solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 10293–10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiatek, J. Specific ion effects and the law of matching solvent affinities: A conceptual density functional theory approach. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Quintana, R.A.; Smiatek, J. Theoretical insights into specific ion effects and strong-weak acid-base rules for ions in solution: Deriving the law of matching solvent affinities from first principles. ChemPhysChem 2020, 21, 2605–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Knape, M.J.; Burkert, O.; Mazzini, V.; Jung, A.; Craig, V.S.; Miranda-Quintana, R.A.; Bluhmki, E.; Smiatek, J. Artificial neural networks for the prediction of solvation energies based on experimental and computational data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 24359–24364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, A.N.; Holm, C.; Smiatek, J. Specific ion effects for polyelectrolytes in aqueous and non-aqueous media: The importance of the ion solvation behavior. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 6243–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiatek, J. Enthalpic contributions to solvent–solute and solvent–ion interactions: Electronic perturbation as key to the understanding of molecular attraction. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 174112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, C.; Steinhauser, O. On the dielectric conductivity of molecular ionic liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 114504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, A.N.; Zeman, J.; Holm, C.; Smiatek, J. Preferential solvation and ion association properties in aqueous dimethyl sulfoxide solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 31312–31322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, A.; Oldiges, K.; Heuer, A.; Winter, M.; Cekic-Laskovic, I.; Holm, C.; Smiatek, J. Electrolyte solvents for high voltage lithium ion batteries: Ion pairing mechanisms, ionic conductivity, and specific anion effects in adiponitrile. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2018, 20, 25861–25874. [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, A.; Smiatek, J. Mixtures of LiTFSI and urea: Ideal thermodynamic behavior as key to the formation of deep eutectic solvents? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12279–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, D.; Lubbers, N.; Germann, T.C. Evaluating diffusion and the thermodynamic factor for binary ionic mixtures. Phys. Plasmas 2020, 27, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.G.; Buff, F.P. The statistical mechanical theory of solutions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 1951, 19, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. Statistical Thermodynamics for Chemists and Biochemists; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, V.; Kang, M.; Aburi, M.; Weerasinghe, S.; Smith, P.E. Recent applications of Kirkwood-Buff theory to biological systems. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.E. Chemical potential derivatives and preferential interaction parameters in biological systems from Kirkwood-Buff theory. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiatek, J. Aqueous ionic liquids and their influence on protein conformations: An overview on recent theoretical and experimental insights. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 233001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprzeska-Zingrebe, E.A.; Smiatek, J. Aqueous ionic liquids in comparison with standard co-solutes. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.M.; Krüger, P.; Schnell, S.K.; Vlugt, T.J.; Kjelstrup, S.; Bedeaux, D. Kirkwood–Buff integrals: From fluctuations in finite volumes to the thermodynamic limit. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157, 130901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, S.H.; Wolff, L.; Becker, T.M.; Bardow, A.; Vlugt, T.J.; Moultos, O.A. Finite-size effects of binary mutual diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theo. Comput. 2018, 14, 2667–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, S.H.; Bardow, A.; Vlugt, T.J.; Moultos, O.A. Generalized form for finite-size corrections in mutual diffusion coefficients of multicomponent mixtures obtained from equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation. J. Chem. Theo. Comput. 2020, 16, 3799–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosen-Runge, F.; Hennig, M.; Zhang, F.; Jacobs, R.M.; Sztucki, M.; Schober, H.; Seydel, T.; Schreiber, F. Protein self-diffusion in crowded solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11815–11820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, J.A.; Verkman, A. Crowding effects on diffusion in solutions and cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, B.; Simonson, T. Implicit solvent models. Biophys. Chem. 1999, 78, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onufriev, A. Implicit solvent models in molecular dynamics simulations: A brief overview. Ann. Rep. Comput. Chem. 2008, 4, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kalz, E.; Vuijk, H.D.; Abdoli, I.; Sommer, J.U.; Löwen, H.; Sharma, A. Collisions enhance self-diffusion in odd-diffusive systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 090601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowen, H.; Szamel, G. Long-time self-diffusion coefficient in colloidal suspensions: Theory versus simulation. J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 1993, 5, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Noyola, M. Long-time self-diffusion in concentrated colloidal dispersions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 60, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, G.K. Brownian diffusion of particles with hydrodynamic interaction. J. Fluid Mech. 1976, 74, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felderhof, B.U. Diffusion of interacting Brownian particles. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1978, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Hess, W.; Klein, R. Self-diffusion of spherical Brownian particles with hard-core interaction. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 1982, 111, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebon, G.; Jou, D.; Casas-Vázquez, J. Understanding Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, P.W.; de Paula, J. Physical Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lecce, S.; Albrecht, T.; Bresme, F. A computational approach to calculate the heat of transport of aqueous solutions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiechowicz, J.; Marchenko, I.G.; Hänggi, P.; Łuczka, J. Diffusion coefficient of a Brownian particle in equilibrium and nonequilibrium: Einstein model and beyond. Entropy 2022, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M.P.; Tildesley, D.J. Computer Simulation of Liquids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronk, S.; Páll, S.; Schulz, R.; Larsson, P.; Bjelkmar, P.; Apostolov, R.; Shirts, M.R.; Smith, J.C.; Kasson, P.M.; van der Spoel, D.; et al. GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gunsteren, W.F.; Billeter, S.; Eising, A.; Hünenberger, P.; Krüger, P.; Mark, A.; Scott, W.; Tironi, I. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide; Vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich: Zurich, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gunsteren, W.F.; Berendsen, H.J. A leap-frog algorithm for stochastic dynamics. Mol. Simul. 1988, 1, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, I.C.; Hummer, G. System-size dependence of diffusion coefficients and viscosities from molecular dynamics simulations with periodic boundary conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 15873–15879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P.; Schnell, S.K.; Bedeaux, D.; Kjelstrup, S.; Vlugt, T.J.; Simon, J.M. Kirkwood–Buff integrals for finite volumes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 4, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D. Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Brosz, M.; Adebar, N.; Burkert, O.; Schulze, M.; Smiatek, J. Influence of co-solutes and solvents on diffusion interaction parameters in multicomponent solutions: New insights through the Kirkwood–Buff theory. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 10381–10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginn, E.J.; Messerly, R.A.; Carlson, D.J.; Roe, D.R.; Elliot, J.R. Best practices for computing transport properties 1. Self-diffusivity and viscosity from equilibrium molecular dynamics [article v1. 0]. Liv. J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2019, 1, 6324. [Google Scholar]

- Smiatek, J.; Sega, M.; Holm, C.; Schiller, U.D.; Schmid, F. Mesoscopic simulations of the counterion-induced electro-osmotic flow: A comparative study. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 244702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, W.; Baschnagel, J. Stochastic Processes: From Physics to Finance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rex, M.; Löwen, H. Dynamical density functional theory for colloidal dispersions including hydrodynamic interactions. Europ. Phys. J. E 2009, 28, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K.E. Kirkwood–Buff solution theory: Derivation and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1994, 23, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulgin, I.L.; Ruckenstein, E. The Kirkwood-Buff theory of solutions and the local composition of liquid mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 12707–12713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tovey, S.; Holm, C.; Smiatek, J. Self- and Fick Diffusion Coefficients in Implicit Solvent Simulations: Influence of Local Aggregation Effects and Thermodynamic Factors. Liquids 2025, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040036

Tovey S, Holm C, Smiatek J. Self- and Fick Diffusion Coefficients in Implicit Solvent Simulations: Influence of Local Aggregation Effects and Thermodynamic Factors. Liquids. 2025; 5(4):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleTovey, Samuel, Christian Holm, and Jens Smiatek. 2025. "Self- and Fick Diffusion Coefficients in Implicit Solvent Simulations: Influence of Local Aggregation Effects and Thermodynamic Factors" Liquids 5, no. 4: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040036

APA StyleTovey, S., Holm, C., & Smiatek, J. (2025). Self- and Fick Diffusion Coefficients in Implicit Solvent Simulations: Influence of Local Aggregation Effects and Thermodynamic Factors. Liquids, 5(4), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040036