Abstract

This work reports on novel acid–base conjugate pairs of monocationic allyldiamidinium and dicationic diamidinium salts, some of which are ionic liquids (ILs) at ambient temperatures. A series of allyldiamidinium salts of the general formula [C3H(NRMe)4]X (R = Me, Et, Pr, allyl, CH2CH2OMe; X = Cl, bistriflimide, dicyanamide) were prepared from C3Cl4 or C3Cl5H and the appropriate secondary amine, RNMeH. Alkylated ethylenediamines similarly yield bicyclic allyldiamidinium salts, whereas longer diamines (H2N(CH2)nNH2 (n = 3, 4, 5)) were isolated as their conjugate acids, the diamidinium dicationic salts [C3H2(HN(CH2)nNH)2]X2. The salts were characterized by NMR, ES-MS, DSC, TGA, and miscibility or solubility studies. Additionally, the ILs were characterized by their viscosities. The conductivities of the diamidinium ILs were also measured, and this allowed for an investigation of their Walden parameters. In contrast to expectations, since the ion pairing and clustering were expected to be significant, this showed them to be “superionic”. Previous reports of Walden plots of dicationic ILs were found to be erroneous, and a reanalysis of the literature data found that all reported dicationic and even tetracationic ILs can be classified as superionic. The salts [C3H(NMe2)4]Cl, [C3H(EtN(CH2)2NEt)2]OTf, and [C3H2(HN(CH2)nNH)2]Cl2 (n = 3, 4, 5) were also characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

1. Introduction

Ionic liquids (ILs) constitute a class of compounds that are composed solely of ions in the liquid state [1]. The traditional definition requires them to, arbitrarily, have a melting point below 100 °C. The combination of consisting of ions and being in the liquid state gives them a variety of useful and interesting properties; most notably, ionic conductivity and close to zero vapour pressure. Consequently, ILs have gained significant attention due to their applications in a wide range of fields, such as electrochemistry, pharmaceutical synthesis, and sensing devices. In recent years, the research on ILs has dramatically expanded, leading to a better understanding of their properties and the development of new applications. Nonetheless, there is a considerable need for new ionic liquids with novel properties.

Our previous work on ionic liquids focused on triaminocyclopropenium (TAC) salts [2,3,4,5]. These are readily prepared by the treatment of tetrachlorocyclopropene (or pentachlorocyclopropane) with secondary amines (Scheme 1). These were first reported in 1971 by Yoshida and Tawara [6]. They have been found to be remarkably stable due to π donation to the aromatic ring by the three amino groups, which leads to a high-lying HOMO and, consequently, weak interactions with anions as well as the easy synthesis of stable radical dications [7,8,9,10]. Yoshida reported that hydrolysis of [C3(NMe2)3]+ in strong base leads to the formation of the allyldiamidinium [CH(C(NMe2)2)2]+ ([1a]+) (along with the cyclopropenone C3(NMe2)2O), although in just a 9% yield) [11]. Taylor and coworkers subsequently reported that similar cations, [CH(C(NRH)2)2]+ ([2a–d]+), formed directly from pentachlorocyclopropane (or tetrachlorocyclopropene) by reaction with primary amines (RNH2 (R = nPr, iPr, nBu, or tBu)), although the nPr and nBu derivatives were not isolated as pure materials [12,13,14]. Addition of acid to an allyldiamidinium can generate a diamidinium dication [CH2(C(NR2)2)2]2+ ([2a–dH]2+) [12,13], whereas strong base can generate tetraaminoallenes ((NR2)2C=C=C(NR2)2) when the amino groups are dialkylated (Scheme 2a) [15]. The allyldiamidinium cation has two main types of resonance structures, of which there are four versions of each structure, shown in Scheme 2b. Formally, these are described as N-alkyl-N-[1,3,3-triamino-2-propenylidene]alkylaminium salts. Unlike most allyls, there is a negative formal charge on the central carbon atom, and that is the position of protonation to form a diamidinium dication.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of C3Cl4 (and C3Cl5H) with primary and secondary amines.

Scheme 2.

(a) Acid–base relationships of diamidinium, allyldiamidinium, and tetraaminoallene species with dialkylated amino groups; (b) resonance forms for the allyldiamidiniums (there are four equivalent structures for each type).

As part of our IL research program, we wished to investigate the properties of allyldiamidinium and diamidinium salts. We considered that the highly delocalized nature of these cations, as well as their Brønsted acid–base properties, could make these interesting species for IL-based applications. Typically, deprotonation of a protic ionic liquid generates an uncharged molecule which is not an ionic liquid. However, deprotonation of a diamidinium ionic liquid would still leave a cationic species, and it would remain as an IL.

A variety of routes have been reported for the synthesis of allyldiamidinium salts. Viehe and coworkers reported a stepwise route in which [Cl2C=NMe2]+ reacts with MeCONMe2 to give the dichlorodiamino allyl cation [CH(CCl(NMe2))2]+, which can be treated with Me2NH to generate [CH(C(NMe2)2)2]+ (Scheme 3) [15,16]. More recently, the groups of both Do and Clyburne reported that the addition of a primary amine with a tertiary alkyl group, such as tBuNH2 or 1-adamantylamine, results in a 1,3-dimethylamino shift to give an allyldiamidinium cation ([CH(C(NMe2)2)(C(NRH)2)]+) (Scheme 3) [17,18]. In contrast, primary amines with secondary alkyl or aryl groups under basic conditions lead to 1,3-diamino addition and formation of amino-functionalised β-diketimines CH(C(NMe2)(NR))2 (R = Ph, 2,6-Me2C6H3, 2,6-iPr2C6H3), which can be converted with base to the β-ketiminato or acid to the allyldiamidinium (Scheme 3) [18]. It should also be noted that the introduction of protic amino groups generates a more complex system of acid–base-related species (Scheme 4). Additionally, Surman has reported that the use of diamines (N,N-diethylethylenediamine and 1,3-diaminopropane) in a direct reaction with C3Cl5H generates allyldiamidinium salts in good to excellent yields and could be converted to diamidiniums with added acid; however, these impure chloride salts were only characterized by NMR [13].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of allyldiamidiniums from [Cl2C=NMe2]+ [15,16,17,18].

Scheme 4.

Acid–base relationships of diamidinium species with protic amino groups.

We sought simple and more generalizable synthetic routes than those described above. Here, we report on synthetic routes directly from C3Cl5H to allyldiamidinium and diamidinium ILs by using a variety of diamines, and some properties of their salts. The synthesis of [1a]Cl and [CH(C(NMeEt)2)2]Cl ([1b]Cl) directly from C3Cl5H has been briefly discussed by us previously [3].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Remarks

All operations were performed using standard Schlenk techniques with a dinitrogen atmosphere to reduce exposure to water. C3Cl5H, NEt3, n-BuNH2, N-methylethylenediamine, N,N′-diethylethylenediamine, propane-1,3-diamine, butane-1,4-diamine, N-methyl-1,3-propanediamine, N-ethyl-1,3-propanediamine, N-butyl-1,3-propanediamine, and 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine were obtained commercially and distilled prior to use. Aqueous dimethylamine, lithium bistriflimide (LiNTf2), sodium dicyanamide (NaDCA), lithium triflate (LiOTf), and dry solvents were used as obtained commercially. NEtMeH was prepared by a modification of methods described by Lucier and Wawzonek [19,20,21]. 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded using either an Agilent MR 400 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or a JEOL ECZ400S (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) NMR spectrophotometer at 400 or 100 MHz, respectively, with tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. Mass spectra were recorded using a maXis 3G UHR-Qq-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany); this was coupled to a Dionex Ultimate 3000LC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For the positive-ion mode, 5 µL of sample was injected into a flow of 50-50 water (0.5% formic acid)/acetonitrile at 0.2 mL/min to the mass spectrometer. Microanalyses were performed by Campbell Microanalytical Laboratory, Dunedin. DSC was performed on a PerkinElmer DSC 8000 (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) and calibrated with indium (156.60 °C) and cyclohexane (−87.0 and 6.5 °C): samples of 5–10 mg mass were sealed in a vented aluminium pan and placed in the furnace with a 50 mL min−1 nitrogen stream; the temperature was raised at 10 °C min−1. TGA data were collected on dried samples using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) at 1 °C min−1 and 10 °C min−1. Viscosities were measured using an Anton-Paar MCR 302 Rheometer CP25 (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria) cone-and-plate measuring system. A CP 25 cone was used for the highly viscous samples. Viscosities were measured over the temperature range 20 to 90 °C. Temperature was controlled through a water connector attached to the base unit. All sample measurements were performed using RheoCompass (version 1.36.2228) software. The instrument was set to zero gap, and the sample was placed to the centre of the 50 mm cone. Measurements were repeated three times. The accuracy of the viscosity measurements was ±1.0% of full-scale range. Conductivities were measured using an EDT direct-ion conductivity cell. The instrument was calibrated with 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solution. Miscibility studies were carried out by taking 0.5 mL of sample and adding, stepwise, 10 × 0.05 mL of solvent followed by 9 × 0.5 mL of solvent. After each addition of solvent, the sample was mixed and allowed to equilibrate at 25 °C to determine whether it is miscible or immiscible.

Prior to physicochemical measurements, samples were azeotrope-dried using either isopropanol or ethanol (typically 3 × 50 mL solvent for <10 mL sample followed by placement under vacuum overnight) to a water content of less than 350 mg·L−1. The presence of even small amounts of water is well known to affect property measurements. Most significantly, viscosities are reduced by the presence of water, so these measurements should be considered as a lower limit of their true values.

2.2. X-Ray Crystallography

A Rigaku Supernova, Dual Cu/Mo, Atlas diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the crystallographic studies. Suitable single crystals were selected and mounted on a nylon loop immersed in perfluorinated oil. The crystal was kept at 120 K during data analysis. SHELXT (version 2019) software was used for solving the structures, and SHELXL (version 2019) was used for structure refinement using least-square minimization.

2.3. Syntheses of Allyldiamidinium and Diamidinium Salts

N-Methyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(dimethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium chloride ([1a]Cl). C3Cl5H (6.91 mL, 49 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of Me2NH (40% water) (44 g, 392 mmol) at 0 °C for an hour. The solution was stirred overnight at ambient temperature to yield a product mixture of [1a]+, [C3(NMe2)3)]+ (in a 1:4 ratio) and [Me2NH2]+. After removing the solvent, the mixture was dissolved in acetonitrile/toluene (2:1) and kept in the freezer overnight to crystallize out the ammonium salts. [C3(NMe2)3)]Cl was removed by acidification with aqueous HCl and extraction with CHCl3. The solvent from the remaining solution was removed in vacuo, dissolved in acetone, and kept in a freezer to crystallize colourless crystals of [(Me2N)2CCHC(NMe2)2]Cl.2CHCl3 (2.44 g, 10%) [17]. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 3.55 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.19 (m, 24H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 168.99 (CCHC), 42.59 (NCH3), 41.10 (CCHC). EI-MS: found m/z 213.2075 (M+); calcd: 213.2074 (M+).

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium chloride ([1b]Cl). C3Cl5H (4.312 g, 20.14 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (150 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Triethylamine (16.49 g, 163 mmol) and N-ethylmethylamine (6.024 g, 102 mmol) were added dropwise, and the solution was then stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The reaction mixture was heated to reflux 5 h before removing the dichloromethane and excess amine in vacuo. Acetone (150 mL) was added to the solution, the precipitated ammonium salt was filtered off, and the acetone was removed in vacuo. Distilled water (50 mL) was added to the product and the pH adjusted to 9–10.5 by adding aqueous NaOH. The product was washed using diethylether (3 × 100 mL) to remove the excess amine, and the solution was neutralized with HCl(aq). The closed-ring product was extracted with chloroform. The aqueous layer was acidified to pH 1–2 and the expected product extracted with dichloromethane. The removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a dark-red viscous liquid (4.8 g, 78%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 3.63 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.29 (m, 8H, NCH2CH3), 2.97 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.77 is H2O, 1.23 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 169.32 (CCHC), 48.22 (NCH2CH3), 38.13 (NCH3), 13.36 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+); calcd: 269.2705 (100%, M+).

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([1b]NTf2). Salt [1b]Cl (1.701 g, 5.58 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (9.801 g, 34.13 mmol) in 100 mL of water for 1 h. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL), the organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a dark-orange liquid (1.5 g, 88%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 3.62 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.24 (m, 8H, NCH2CH3), 2.91 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.56 is H2O, 1.22 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 169.51 (CCHC), 120.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 48.18 (NCH2CH3), 37.85 (NCH2CH3), 13.15 (NCH3). EI MS: found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+); calcd: 269.2705 (100%, M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H33F6N5O4S2 C, 37.15, H 6.05, N 12.74%; found: C 37.30, H 6.05, N 12.56%.

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium dicyanamide ([1b]DCA). Salt [1b]Cl (1.46 g, 4.79 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.854 g, 9.59 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to produce a yellow liquid (0.956 g, 59%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.62 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.42 (q, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 3.14 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.29 (t, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.53 (CCHC), 50.33 (NCH3), 39.38 (NCH2CH3), 38.07 (CCHC), 13.17 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 269.2712 (M+); calcd: 269.2705 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H33N7: C, 60.86, H 9.91, N 29.23%; found: C 59.87, H 10.15, N 29.09%.

N-Ethyl-N-[1,3,3-tris(ethylmethylamino)-2-propenylidene]methanaminium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([1b]OTf). Salt [1b]Cl (2.38 g, 7.81 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. LiCF3SO3 (8.53 g, 54.67 mmol) was added to the solution and stirred for 1 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 75 mL) and washed with water (5 × 100 mL), and the organic layer was dried in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (2.14 g, 65%). 1H NMR (DMSO, 400 MHz): δ 3.64 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.17 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 3.16 is H2O, 2.84 (s, 12H, NCH3), 1.13 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO, 100 MHz): 169.20 (CCHC), 47.89 (NCH2CH3), 37.86 (NCH2CH3), 13.38 (NCH3). EI MS: found m/z 269.2708 (100%, M+); calcd: 269.2705 (100%, M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C16H33N4O3SF3: C, 45.51; H, 7.80; N, 13.27%; found: C, 44.49; H, 7.83; N, 12.29%.

N,N′-[1,3-Bis(n-butylamino)-1,3-propanediylidene]bis[n-butanaminium] chloride ([2cH]Cl2). n-Butylamine (55.00 mL, 56 mmol) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of Cl5C3H (8.90 mL, 69 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (150 mL) at 0 °C in an inert atmosphere. The mixture was stirred overnight, followed by heating to reflux for 5 h. After removing the CH2Cl2 in vacuo, the mixture was dissolved in CHCl3 (50 mL), and ammonium salts were extracted with water (3 × 50 mL). The CHCl3 layer was then taken and the product extracted with water (3 × 50 mL) to yield a light-brown, viscous oil (13 g, 47%) after removal of solvent in vacuo. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 4.03 (s, <2H, CCH2C), 3.30 (t, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.25 (t, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 1.53 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2), 1.27 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 0.82 (two overlapping triplets, 12H, CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, D2O): δ 158.15 (CN2), 44.48 (NCH2), 42.83 (NCH2), 31.03 (NCH2CH2), 28.69 (NCH2CH2), 19.64 (NCH2CH2CH2), 19.40 (NCH2CH2CH2), 13.05 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 12.98 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EIMS (m/z): found: 163.1701 (M2+), 325.3327 (M+); calcd: 163.1699 (M2+), 325.3326 (M+). Characterization was consistent with previous work [10]. Anal. calcd for C19H43N4O0.5Cl2: C 56.12, H 10.65, N 13.78%; found: C 55.65, H 10.72, N 13.82%.

N,N′-[1,3-Bis(n-butylamino)-1,3-propanediylidene]bis[n-butanaminium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([2cH][NTf2]2). Salt [2cH]Cl2 (2.15 g, 5.41 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (4.99 g, 17.4 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was collected and washed using water (4 × 50 mL) and the product dried in vacuo to yield a dark-brown, viscous liquid (3.00 g, 62%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.80 (m, 2H, NH), 7.47 (m, 2H, NH), 4.05 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.34 (m, 8H, NCH2), 1.65 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2), 1.35 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2), 0.91 (m, 12H, CH3). Anal. calcd for C23H42N6O8F12S4: C 31.15, H 4.77, N 9.48%; found: C 31.86, H 4.91, N 9.26%.

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium chloride ([3a]Cl). Salt C3Cl5H (4.309 g, 20.11 mmol) was stirred with dichloromethane (100 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. N-Methylethylendiamine (5.96 g, 80.40 mmol) was added dropwise to the ice-cold mixture and stirred for 2 h. The product solution was decanted from the ammonium chloride precipitate and the solvent removed in vacuo. Dilute NaOH was added and then washed using diethyl ether. The aqueous layer was neutralized and the product then extracted using dichloromethane (3 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed and the product dried in vacuo to yield a light-yellow solid (2.32 g, 53%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 8.79 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.66 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.85 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 161.85 (CCHC), 55.72 (CCHC), 50.52 (NCH2CH2), 42.04 (NCH2CH2), 32.99 (NCH3). EI MS m/z found: 181.1479 (100%, M+); calcd: 181.1453 (100%, M+).

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonylamide)imide ([3a]NTf2). Salt [3a]Cl (2.32 g, 10.71 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (4.22 g, 14.7 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100 mL), and the product was dried in vacuo to yield a brown solid (2.28 g, 46%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 6.09 (s, 2H, NH), 3.72 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.68 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.59 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.90 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 163.54 (CCHC), 119.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 55.98 (CCHC), 50.74 (NCH2CH2), 42.12 (NCH2CH2), 32.92 (NCH3). EI-MS: found m/z 181.1457 (M+); calcd: 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H17F6N5O4S2: C, 28.63, H 3.71, N 15.18%; found: C 28.43, H 3.67, N 14.96%.

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium dicyanamide ([3a]DCA). Salt [3a]Cl (1.14 g, 5.26 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.622 g, 6.99 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a light-yellow oil (0.753 g, 58%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 7.98 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.68 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.55 (t, 3JHH = 7.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.88 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 161.85 (CHCC), 50.55 (CCHC), 50.52 (NCH2CH2), 42.10 (NCH2CH2), 32.98 (NCH3). EI-MS: found m/z 181.1446 (M+); calcd: 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H17N7: C 53.42, H 6.93, N 39.65%; found: C 52.26, H 7.27, N 39.72%.

2-[(1-methyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-imidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([3a]OTf). Salt [3a]Cl (3.073 g, 14.18 mmol) was stirred with LiCF3SO3 (3.043 g, 19.50 mmol) in 100 mL water. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (3 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 100mL) and the product dried in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.374 g, 29%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 7.01 (s, 2H, NH), 3.70 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 3.67 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.55 (t, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2), 2.88 (s, 6H, NCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 161.54 (CCHC), 119.84 (q, 3JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 55.98 (CCHC), 50.76 (NCH2CH2), 42.13 (NCH2CH2), 32.94 (NCH3). EI MS: found m/z 181.1457 (M+); calcd: 181.1448 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C10H17F3N4O3S: C, 36.36, H 5.19, N 16.96%; found: C 36.09, H 5.11, N 16.96%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium chloride ([3b]Cl). N,N′-diethylethylenediamine (2.16 g, 18.66 mmol) and triethylamine (1.94 mL, 13.98 mmol) were added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.04 g, 4.85 mmol) in chloroform at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated ammonium salt was filtered off, and excess solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in slightly basic water (50 mL), and the product was washed with diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL). The aqueous layer was neutralized and the product extracted using chloroform (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo. The crude product was dissolved in chloroform/ethanol (1:3) and passed through a silica column. The product was collected and the solvent removed to yield a yellow liquid (0.861 g, 59%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.67 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.49 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.20 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.14 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.27 (CCHC), 52.71 (CCHC), 46.67 (NCH2CH2), 43.04 (NCH2CH3), 11.93 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: found m/z 265.2383 (M+); calcd: 265.2392 (M+).

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([3b]NTf2). Salt [3b]Cl (0.221 g, 0.735 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (0.337 g, 1.17 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a light-yellow oil (0.212 g, 53%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.60 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.49 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.20 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.15 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.39 (CCHC), 120.04 (q, 1JCF = 321.6 Hz, CF3), 52.70 (CCHC), 46.40 (NCH2CH2), 42.98 (NCH2CH3), 11.75 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 265.2445 (M+); calcd: 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H29F6N5O4S2: C 37.43, H 5.36, N 12.84%; found: C 36.87, H 5.35, N 13.09%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium dicyanamide ([3b]DCA). Salt [3b]Cl (0.371 g, 1.23 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.175 g, 1.97 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a light-yellow oil (0.261 g, 64%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.65 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.56 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.26 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.19 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.43 (CCHC), 120.06 (CN), 52.87 (CCHC), 46.52 (NCH2CH2), 43.09 (NCH2CH3), 11.92 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 265.2424 (M+); calcd: 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H29N7: C 61.60, H 8.82, N 29.58%; found: C 60.94, H 8.60, N 28.80%.

2-[(1,3-diethyl-2-imidazolidinylidene)methyl]-4,5-dihydro-1,3-diethyl-1H-imidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate ([3b]OTf). Salt [3b]Cl (0.27 g, 0.898 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (0.22 g, 1.41 mmol) in distilled water (50 mL) for 4 h. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (0.259 g, 70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.64 (s, 8H, NCH2CH2), 3.51 (s, 1H, CCHC), 3.21 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH3), 1.16 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 12H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.36 (CCHC), 121.04 (q, 1JCF = 322.6 Hz, CF3), 52.69 (CCHC), 46.47 (NCH2CH2), 43.00 (NCH2CH3), 11.83 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: found m/z 265.2397 (M+); calcd: 265.2392 (M+). Microanalysis: calcd for C16H29F3N4O3S: C 46.36, H 7.05, N 13.52%; found: C 45.57, H 7.06, N 13.70%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] chloride ([4H]Cl2). Propane-1,3-diamine (2.22 g, 30.01 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.60 g, 7.503 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred for 1 h. After filtering off the precipitated ammonium salt, the solution was washed using distilled water (3 × 75 mL). The CH2Cl2 was removed to yield a highly hygroscopic, light-orange solid (1.14 g, 71%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.17 (s, NH, 4H), 4.36 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 4 Hz, 8H, NCH2), 2.00 (p, JHH = 4 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.90 (CCH2C), 38.13 (CCH2C), 32.48 (NCH2), 17.79 (NCH2CH2). ES+ m/z found: 91.0766 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 91.0760 (100%, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([4H][NTf2]2). Salt [4H]Cl2 (0.66 g, 2.6 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.445 g, 2.6 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 was added (1.16 g, 4.04 mmol). The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess ammonium salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a brown solid (1.30 g, 67%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.16 (s, NH, 4H), 4.36 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (t, 3JHH = 4 Hz, 8H, NCH2), 2.00 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 156.90 (CCH2C), 39.14 (CCH2C), 32.48 (NCH2), 17.79 (NCH2CH2). ES+ m/z found: 91.0772 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 91.0760 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C13H18F12N6O8S4: C, 21.03, H 2.44, N 11.32%; found: C 21.12, H 2.30, N 11.45%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4H][DCA]2). Salt [4H]Cl2 (1.98 g, 7.82 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.32 g, 7.82 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and NaDCA (0.905 g, 10.16 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange liquid (1.67 g, 68%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.08 (s, 4H, NH), 4.33 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.51 (m, 8H, NCH2), 2.00 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 157.03 (CCH2C), 39.27 (CCH2C), 32.52 (NCH2), 17.81 (NCH2CH2). EI MS: found m/z 91.0755 (M2+); calcd: 91.0760 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C13H18N10: C, 49.67, H 5.77, N 44.56%; found: C 47.45, H 6.30, N 44.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4H][OTf]2). Salt [4H]Cl2 (1.89 g, 7.46 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.28 g, 7.46 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was filtered off and LiOTf (1.51 g, 9.68 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product extracted using chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange solid (0.974 g, 42%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.91 (s, 4H, NH), 3.75 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.31 (m, 8H, NCH2), 1.83 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 156.41 (CCH2C), 121.15 (OTf), 39.04 (CCH2C), 35.09 (NCH2), 17.51 (NCH2CH2). EI MS: found m/z 91.0764 (M2+); calcd: 91.0760 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C11H18F6N4O6S2: C, 27.50, H 3.78, N 11.66%; found: C 26.60, H 3.30, N 11.45%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4aH]Cl2). N-methyl-1,3-propanediamine (1.30 g, 14.8 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (0.99 g, 4.62 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated ammonium salt was filtered off, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted with chloroform and the organic layer washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.1 g, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.31 (s, 2H, NH), 4.60 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.67 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.60 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.37 (s, 6H, NCH3), 2.11 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.71 (CCH2C), 49.63 (NCH2CH2CH2), 40.47 (NCH2CH2CH2), 38.92 (NCH3), 33.35 (CCH2C), 18.92 (NCH2CH2). EI-MS: found m/z 105.0917 (M2+); calcd: 105.0917 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([4aH][NTf2]2). Salt [4aH]Cl2 (0.984 g, 3.50 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (1.27 g, 4.42 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.47 g, 86%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.46 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.45 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2), 3.09 (s, 6H, NCH3), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 49.15 (NCH2), 38.97 (NCH2), 34.29 (NCH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH2CH2). EI MS: found m/z 105.0916 (M2+); calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22F12N6O8S4: C, 23.38, H 2.88, N 10.91%; found: C 24.58, H 2.28, N 10.44%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4aH][DCA]2). Salt [4aH]Cl2 (0.984 g, 3.50 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.498 g, 5.60 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and then washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown liquid (0.784, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.22 (s, 2H, NH), 4.65 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.99 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.83 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 3.63 (s, 6H, NCH3), 2.45 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 49.15 (NCH2), 38.97 (NCH2), 34.22 (NCH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH2CH2). EI MS: found m/z 105.0912 (M2+); calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22N10: C, 52.62, H 6.48, N 40.91%; found: C 52.36, H 7.32, N 39.30%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidinium] triflate ([4aH][OTf]2). Salt [4aH]Cl2 (0.794 g, 2.81 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (0.571 g, 3.65 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (0.975 g, 65%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.46 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.45 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2), 3.09 (s, 6H, NCH3), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.20 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 49.15 (NCH2), 38.97 (NCH2), 34.29 (NCH2), 33.47 (CCH2C), 19.68 (NCH2CH2). EI MS: found m/z 105.0916 (M2+); calcd: 105.0915 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found: C 32.69, H 4.45, N 10.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4bH]Cl2). N-ethyl-1,3-propanediamine (3.85 mL, 31.17 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.67 g, 7.79 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The solvent was removed in vacuo after filtering off the precipitated ammonium salt. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted using chloroform, and the organic layer was washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.4 g, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2CH2CH2), 47.23 (NCH2CH2CH2), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([4bH][NTf2]2). Salt [4bH]Cl2 (1.46 g, 5.63 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (2.51 g, 8.74 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.29 g, 88%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.48 (s, 2H, NH), 4.12 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.53 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.85 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26F12N6O8S4: C, 25.57, H 3.28, N 10.52%; found: C 25.52, H 3.26, N 10.50%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4bH][DCA]2). Salt [4bH]Cl2 (1.34 g, 4.33 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (0.698 g, 7.84 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and then washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.08 g, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2CH2CH2), 47.23 (NCH2CH2CH2), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH3). EI-MS: found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26N10: C, 55.12, H 7.07, N 37.81%; found: C 53.78, H 7.25, N 37.56%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-ethylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4bH][OTf]2). Salt [4bH]Cl2 (1.73 g, 6.32 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (1.57 g, 10.06 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.21 g, 45%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 10.25 (s, 2H, NH), 4.30 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 8H, NCH2CH2CH2) (overlapping with CH2 in ethyl group), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.12 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found: C 33.46, H 4.56, N 10.40%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] chloride ([4cH]Cl2). N-butyl-1,3-propanediamine (4.56 mL, 28.7 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.50 g, 7.00 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The solvent was removed in vacuo after filtering off the precipitated ammonium salt. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted using chloroform, and the organic layer was washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.2 g, 47%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.30 (s, 2H, NH), 4.47 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.67 (t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2N), 3.63 (m, 4H, HNCH2), 3.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.8 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 2.10 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2N), 1.65 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.37 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.97 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.43 (CCH2C), 52.83 (NCH2), 47.23 (NCH2), 39.27 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 29.27 (CCH2C), 20.03 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.82 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 13.84 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 147.1388 (M2+); calcd: 147.1386 (M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([4cH][NTf2]2). Salt [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with LiNTf2 (1.99 g, 6.93 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with dichloromethane (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.35 g, 46%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.44 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.49 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.36 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2N), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.26 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.73 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.28 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.95 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.66 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 29.33 (CCH2C), 19.69 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.53 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 14.16 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 147.1383 (M2+); calcd: 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C21H34F12N6O8S4: C, 29.51, H 4.01, N 9.83%; found: C 30.44, H 4.10, N 10.03%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([4cH][DCA]2). Salt [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with NaDCA (1.99 g, 22.35 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with a chloroform and ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and then washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a white solid (1.35 g, 69%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.44 (s, 2H, NH), 4.04 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.48 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 3.35 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, NCH2CH2CH2) 3.30 (s, H2O), 1.92 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.27 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.89 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (s, CN), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 19.71 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI MS: found m/z 147.1383 (M2+); calcd: 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C21H34N10: C, 59.13, H 8.03, N 32.84%. Calc found: C 58.99, H 8.98, N 32.58%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1-butylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethylsulfonate ([4cH][OTf]2). Salt [4cH]Cl2 (1.67 g, 4.56 mmol) was stirred with LiOTf (1.26 g, 8.08 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The product was extracted with a 4:1 chloroform/ethanol mixture (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brown solid (1.47 g, 61%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): δ 9.89 (s, 2H, NH), 4.16 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.49 (t, 3JHH = 5.5 Hz, 4H, HNCH2CH2CH2), 3.32 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 4H, NCH2) 3.30 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 4H, NCH2), 1.91 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2N), 1.54 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.27 (m, 4H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.87 (t, 3JHH = 7.32 Hz, 6H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 155.75 (CCH2C), 119.92 (q, 1JCF = 324 Hz, CF3), 52.22 (NCH2CH2CH2), 46.87 (NCH2CH2CH2), 33.56 (CCH2C), 29.29 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 19.71 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 18.52 (NCH2CH2CH2), 14.18 (NCH2CH2CH2CH3). EI-MS: found m/z 147.1384 (M2+); calcd: 147.1386 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C19H34F6N4O6S2: C, 38.51, H 5.78, N 9.45%; found: C 38.94, H 5.67, N 10.05%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [4,5,6,7-tetrahydrodiazepinium] chloride ([5H]Cl2). 1,4-Butanediamine (2.92 g, 33.12 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (1.77 g, 8.26 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at 0 °C and the solution stirred for one hour. After filtering off the precipitated ammonium salt and removing the solvent, the residual ammonium salt was removed by dissolving in dichloromethane (100 mL) and washing with water (4 × 50 mL). Removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a light-yellow solid (1.56 g, 67%). The solid was recrystallized using a vapour diffusion technique to yield colourless crystals. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.05 (s, NH, 4H), 4.24 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.65 (m, NCH2, 8H) 2.04 (m, NCH2CH2, 8H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 161.13 (CCHC), 44.14 (NCH2), 35.73 (CCH2C), 26.16 (NCH2CH2). ES+ m/z: found 105.0921 (100%, M2+). Calcd. 105.0916 (100%, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [4,5,6,7-tetrahydrodiazepinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([5H][NTf2]2). Salt [5H]Cl2 (1.608 g, 5.72 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.971 g, 5.72 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL). The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 (2.55 g, 8.88 mmol) added. The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted with diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess ammonium salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a red solid (1.12 g, 33%). 1H NMR (DMSO, 400 MHz): 9.43 (s, NH, 4H), 3.59 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.30 is H2O, 3.51 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H), 1.92 (m, NCH2CH2CH2CH2, 8H). 13C NMR (DMSO, 100 MHz): 161.13 (CCHC), 35.73 (CCH2C), 44.14 (NCH2CH2CH2CH2), 26.16 (NCH2CH2CH2CH). ES+ m/z found: 105.0919 (100%, M2+). Calcd: 105.0916 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H22F12N6O8S4: C, 23.38, H 2.88, N 10.91%; found: C 23.28, H 2.28, N 10.44%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydrodiazocinium] chloride ([6H]Cl2). 1,5-pentanediamine (2.86 g, 28.0 mmol) was added dropwise to C3HCl5 (1.50 g, 7.00 mmol) in chloroform (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred overnight under an inert atmosphere. The precipitated ammonium salt was filtered off, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The product was dissolved in distilled water and washed several times with diethyl ether to remove unreacted amine. The product was extracted with chloroform and the organic layer washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a yellow solid (1.31 g, 61%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.00 (s, 4H, NH), 4.29 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.73 (q, JHH = 6.4 Hz, 8H, NCH2(CH2)3CH2), 1.98 (m, 8H, N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2), 1.65 (m, 4H, N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 160.21 (CCH2C), 42.13 (NCH2(CH2)3CH2), 36.63 (CCH2C), 29.48 (N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2), 20.27 (N(CH2)2(CH2)2CH2). EI-MS: found m/z 119.1073 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Td at 10 °C/min = 330 °C.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] chloride ([7H]Cl2). 2,2-Dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine (8.21 g, 80.4 mmol) was added dropwise to C3Cl5H (4.30 g, 20.10 mmol) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at 0 °C and the reaction stirred for one hour. After filtering off the precipitated ammonium salt and removing the solvents in vacuo, the residual ammonium salt was removed by dissolving in dichloromethane (100 mL) and washing with water (4 × 50 mL). Removal of dichloromethane in vacuo yielded a light-yellow liquid which solidified overnight (2.41 g, 56%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 11.24 (s, NH, 4H), 4.44 (s, CCH2C, 1H), 3.15 (s, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2, 8H), 1.05 (s, CH3, 12H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.37 (CCH2C), 50.41 (NCH2 CH2), 49.49 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.17 (C(CH3)2. ES+ m/z: found 119.1070 (100%, M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (100%, M2+).

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([7H][NTf2]2). Salt [7H]Cl2 (1.08 g, 3.49 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (0.592 g, 3.49 mmol) in distilled water (100 mL). The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiNTf2 (1.53 g, 5.33 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 2 h. The product was extracted using diethyl ether (4 × 75 mL) and washed with distilled water (4 × 50 mL) to remove excess ammonium salt. The organic layer was dried to yield a brown solid (1.968 g, 71%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): 9.79 (s, NH, 4H), 3.72 (s, CCH2C, 2H), 3.04 (s, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2, 8H), 0.96 (s, CCH3, 12H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 156.37 (CCH2C), 50.41 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.49 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.17 (C(CH3)2). ES+ m/z found: 119.1076 (100%, M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (100%, M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26F12N6O8S4: C 25.57, H 3.28, N 10.52%; found: C 25.50, H 3.26, N 10.51%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] dicyanamide ([7H][DCA]2). Salt [7H]Cl2 (2.41 g, 7.79 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.32 g, 7.79 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and NaDCA (1.17 g, 10.27 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange liquid (1.23 g, 51%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.22 (s, 4H, NH), 4.34 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.15 (s, 8H, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 1.05 (s, 12H, CCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.58 (CCH2C), 50.49 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.45 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.21 (C(CH3)2). EI MS: found m/z 119.1074 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C17H26N10: C 55.12, H 7.07, N 37.81%; found: C 54.57, H 7.08, N 37.16%.

2,2′-Methylenebis [3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-5,5-dimethylpyrimidinium] trifluoromethanesulfonate ([7H][OTf]2). Salt [7H]Cl2 (2.33 g, 7.53 mmol) was stirred with AgNO3 (1.27 g, 7.53 mmol) in 100 mL of distilled water. The precipitated AgCl was removed and LiOTf (1.94 g, 12.4 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 4 h and the product was extracted with chloroform (4 × 75 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield an orange solid (1.56 g, 47%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.96 (s, 4H, NH), 4.29 (s, 2H, CCH2C), 3.15 (s, 8H, NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 1.04 (s, 12H, CCH3). 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.58 (CCH2C), 50.49 (NCH2C(CH3)2CH2), 49.45 (CCH2C), 25.49 (C(CH3)2), 24.21 (C(CH3)2). EI MS: found m/z 119.1072 (M2+); calcd: 119.1073 (M2+). Microanalysis: calcd for C15H26F6N4O6S2: C, 33.58, H 4.88, N 10.44%; found: C 32.69, H 4.45, N 10.40%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

During our earlier work on TAC salts as ionic liquids, we observed the formation of significant amounts of the allyldiamidiniums [1a]Cl and [1b]Cl during the syntheses of [C3(NMe2)3]Cl and [C3(NEtMe)3]Cl, respectively, via ES-MS of the crude product (Scheme 5) [3]. These species are easily separated from TAC salts, as they are much more soluble in aqueous acid (as the diamidinium dications). Reaction of C3Cl5H with longer-chain secondary amines with one methyl group, RNMeH (R = Pr, allyl, CH2CH2OMe), also show the formation of allyldiamidiniums ([1c–e]+), but in lower amounts, so they were not able to be isolated in reasonable yields. Single crystals of the salt [1a]Cl were isolated as a chloroform solvate, and the solid-state structure is reported below. In contrast, [1b]Cl is a viscous liquid at ambient temperature, so we prepared additional ionic liquids of [1b]+ with the bistriflimide (NTf2−), dicyanamide (DCA), and triflate (OTf−) anions by metathesis with LiNTf2, NaDCA, and LiOTf, respectively. Unfortunately, steric factors appear to limit the viability of a direct reaction of C3Cl4 or C3Cl5H with secondary amines as a general route to allyldiamidinium ILs, since secondary amines with no methyl groups only form TAC salts upon reaction with C3Cl4. Species [2c]+, which had been reported by Surman as the diamidinium dichloride but not isolated [13], was isolated by us as an ionic liquid chloride salt in the diamidinium form [2cH]Cl2 and similarly converted to the bistriflimide diamidinium salt [2cH][NTf2]2.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of allyldiamidinium chlorides.

We decided to further investigate Surman’s report on the use of diamines to synthesise allyldiamidiniums. We prepared two cations with the ethylene backbone: one asymmetric, with a Me group on one N atom and H on the other ([3a]+), and one symmetric, with an ethyl group on each N atom ([3b]+) (Scheme 6). The use of non-alkylated ethylenediamine generates a complex product mixture according to its ES-MS, probably due to the formation of oligomeric species. The salts [3a]Cl and [3b]Cl were also converted to NTf2−, DCA, and OTf− salts.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of allyldiamidinium chloride salts using ethylenediamines.

Surman also reported the addition of 1,3-diaminopropane to yield the bicyclic diamidinium, a bis(tetrahydropyrimidinium), with four NH groups, [4H]2+ [13]. Along with this species, we prepared analogues with two NH groups and two alkylated (Me, Et, and Bu) N atoms ([4aH]2+, [4bH]2+, and [4cH]2+, respectively), as well as an analogue with an alkylated backbone from 1,3-diamino-2,2-dimethylpropane ([7H]2+) (Scheme 7). The NTf2−, DCA, and OTf− salts were prepared for [4H]2+, [4a–cH]2+, and [7H]2+. Larger-ring analogues were also prepared from 1,4-diaminobutane ([5H]2+) and 1,5-diaminopentane ([6H]2+), which yield the bis(tetrahydrodiazapinium) salt [5H]Cl2 and the bis(hexahydrodiazocinium) salt [6H]Cl2, respectively, the former of which was also converted to the bistriflimide salt.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of diamidinium dichloride salts with larger rings.

It should be noted that in some cases the chloride salt was isolated as the allyldiamidinium and in other cases as the diamidinium. Significantly, [1b]Cl was isolated as the allyldiamidinium, despite being extracted with CH2Cl2 from an aqueous solution at pH 1–2. In contrast, [2cH]Cl2 was obtained as the diamidinium, despite being isolated by extraction from a basic aqueous solution. There are several factors in play here, most importantly, the pKa of the diamidinium species, and the distribution coefficients of the diamidinium and allyldiamidinium between the aqueous and organic layers. It might be expected that the dications would have less preference for the organic layer; however, NH–Cl− hydrogen bonding is very strong, and some of these species are able to strongly chelate the chloride ions, as evidenced by the difficulties experienced when carrying out the subsequent anion metathesis (addition of AgNO3 is required to remove the chloride). Notably, the solid-state structures of [4H]Cl2, [5H]Cl2, and [6H]Cl2 display non-solvated bis-chelated dichloride diamidinium structures (Section 3.2). These bis-chelated structures not only stabilize the diamidinium species but also give neutral clusters that would be expected to have improved solubility in polar organic solvents. Thus, all of the salts with four NH groups were obtained as diamidiniums, whereas all of the salts with no NH groups were obtained as allyldiamidiniums. In the cases of salts with two NH groups, salts [4a–cH]Cl2 were obtained as the diamidinium, whereas [3a]Cl was obtained as the allyldiamidinium.

3.2. X-Ray Crystallography

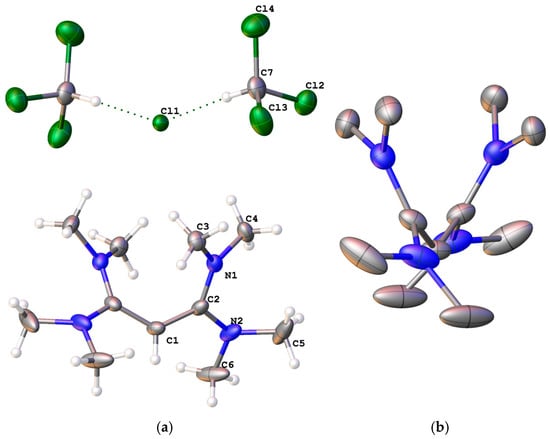

The salts [1a]Cl.2CHCl3, [3b]OTf, [4H]Cl2, [5H]Cl2, and [6H]Cl2 were characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Crystallographic data, as well as tables of the bond distances and angles, are provided in the Supporting Information (SI). [1a]Cl was isolated as a dichloroform solvate in the monoclinic space group C2/c. The chloride and [1a]+ cation sit on crystallographic C2 axes. Two asymmetric units (one formula unit) with the atomic labelling scheme are shown in Figure 1a. The chloride solvate species is not quite linear, with a C7–Cl–C7′ angle of 148.57(10)°. Unlike the other allyldiamidinium salts that have been reported previously, this cation has equivalent amidinium moieties, so the delocalization is equal on both sides. The equivalent C–C bond distances of 1.405(2) Å are typical for a C–C bond order of 1.5 and lie between the two C–C bond distances for the other reported examples, except for [(Me2N)2CCHC(NH-t-Bu)2]Cl.H2O.Me2CO [18], which has very similar but slightly longer distances (1.411(2) and 1.407(2) Å). Steric crowding between the C3 methyl groups prevents planarity of the allyldiamidinium (Figure 1b). Most of this is relieved by rotation about the C1–C2, C2–N1 and C2–N2 bonds; thus, the twist angles between the various adjacent planes (C2-C1-C2′, C1-C2-N1-N2, C2-N1-C3-C4, and C2-N2-C5-C6) are very similar (between 27 and −29°), and most of the atoms are trigonal planar (for C1, C2, and N1, the sum of angles > 359.7°). However, N2 is slightly pyramidal, with a sum of angles of 356.2°. This has no significant structural effect, as the C2–N distances are essentially the same at 1.352(3) and 1.358(2) Å, which are slightly longer than the C–N bond distances in pyridine (1.337 Å), as the C–N bond order should be less than 1.5. The N–Me distances average 1.46 Å. Oeser reported the structure of this cation as the perchlorate salt in 1974; the structure is essentially the same, with C–C distances reported to be 1.41 and 1.42 Å and the C–N distances found to be 1.33–1.37 Å [22].

Figure 1.

(a) Labelled solid-state structure of one formula unit of [1a]Cl.2CHCl3; (b) side view of the cation [1a]+.

[3b]OTf was isolated in the triclinic space group P-1 with one cation and one anion in the asymmetric unit (Figure 2a). The constrained five-membered rings are both planar along with the central C1 atom. However, steric interactions between the N2 and N3 ethyl groups force these to have a twist angle with respect to each other of 47.83(6)° (Figure 2b). Additionally, the ethyl groups are bent out of the plane by 21.79(11)° for the N2 ethyl and by 21.48(9)° for the N3 ethyl. Interestingly, the ethyl groups on the other side of the rings are bent in the opposite direction, despite there being no obvious steric interactions, by 12.36(11)° for the N1 ethyl and by 17.54(9)° for the N4 ethyl. Presumably this is a consequence of the π delocalization through the allyl atoms. N1 is the most planar N atom, and it also has the shortest N–Callyl distance (1.345(2) versus 1.352(2)–1.359(2) Å)—including the related distances in [1a]Cl), presumably due to the more efficient π-bonding overlap with C3. The allyl C–C distances are also essentially the same as in [1a]Cl: 1.400(2) and 1.402(2) Å versus 1.405(2) Å.

Figure 2.

(a) Labelled solid-state structure of the asymmetric unit (=one formula unit) of [3b]OTf; (b) side view of the cation [3b]+ through the planes of the five-membered rings.

Both [1a]+ and [3b]+ cations are more symmetric than most previously reported allyldiamidiniums. Do et al. drew the cation [(Me2N)2CCHC(NHtBu)2]+ as having a localized, non-charged bis(dimethylamino) group and a delocalized bis(t-butylamino)amidinium cationic group, analogous to the asymmetric resonance structure shown in Scheme 2b, but described it as a highly delocalized system since the C–C distances are essentially the same: 1.411(2) and 1.407(2) Å, and the N–C distances fall in the range 1.348–1.366 Å [18]. Clyburne and coworkers reported a structure of the same salt, but with a different solvate [17]. The C–C distances in this case are slightly different (1.4165(12) and 1.4017(12) Å), but otherwise the structures are very similar. Clyburne also reported an adamantyl analogue, [(Me2N)2CCHC(NHAdm)2][PF6] (Adm = adamantyl), which has quite different C–C distances of 1.418(3) and 1.394(3) Å as well as different C–N distances (1.358(4) and 1.369(3) Å for C–NMe2 and 1.344(3) and 1.341(3) Å for C–NAdm2), which are consistent with an asymmetric resonance structure. There appears to be no significant conformational difference between the two amidinium ends that would explain this asymmetry. In contrast, the structure of [2d]NO3, reported by Taylor and coworkers, is significantly asymmetric due to an intramolecular NH–N hydrogen bond that causes the hydrogen bond acceptor N atom to have a pyramidal coordination geometry [12]. The pyramidal N–Callyl distance is consequently long (1.409(5) Å versus 1.335(6)–1.345(5) Å for the other N–Callyl distances), and the corresponding C–C distance is much shorter than the other: 1.376(5) Å versus 1.417(5) Å.

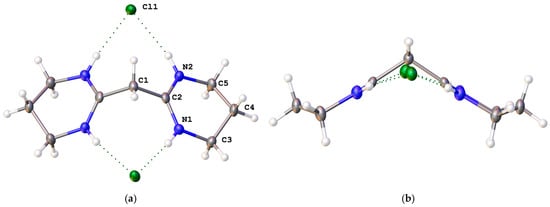

The solid-state structure of [4H]Cl2 was found to pack in the orthorhombic space group Pbcn with half of the cation and one anion in the asymmetric unit (Figure 3a). A C2 axis passes through the central C atom, C2. Five of the atoms in each six-membered ring are in the same plane, with one out of the plane to give an envelope-like conformation for the rings (Figure 3b). Each chloride is chelated by two NH groups, one from each amidinium. The hydrogen-bonding parameters are provided in the SI. As expected, the bonds to the methylene groups are consistent with single bonds, whereas the amidinium N–C bonds are consistent with a bond order of 1.5 (1.311(2) and 1.3154(19) Å) and are slightly shorter than in the allyldiamidiniums above, which have a formal bond order of 1.25.

Figure 3.

(a) Labelled solid-state structure of [4H]Cl2; (b) side view of [4H]Cl2 through the amidinium planes.

Salt [5H]Cl2 forms in the monoclinic space group P21/n with two dications and four chlorides in the asymmetric unit (Figure 4a). The two dications adopt the same conformational arrangement in which one seven-membered ring has a twisted-envelope-like conformation and the other has a distorted twist conformation (Figure 4b). The twist in each ring arises because the methylene groups attached to the amidinium CN2 atoms lie out of the CN2 plane. In the twisted envelope (top right and bottom left of Figure 4b), the N2–C2 vector forms an angle of 9.61(10)° with the amidinium plane (C1-C2-N1-N2), whereas the N1–C7 vector forms an angle of −12.31(10)°. In the distorted twist ring (top left and bottom right of Figure 4b), the N4–C8 vector has an angle of 18.4(1)° to the amidinium plane (C1-C3-N3-N4), whereas the N3–C11 vector forms an angle of 18.0(1)°. There are similar twists in the other dication. As with [4H]2+, the amidinium C–N bond distances are short; they lie in the range 1.3107(16) to 1.3173(17) Å. Again also, each chloride is chelated by two NH groups, one from each amidinium.

Figure 4.

(a) Labelled solid-state structure of [5H]Cl2; (b) side view of [5H]Cl2 through the amidinium planes.

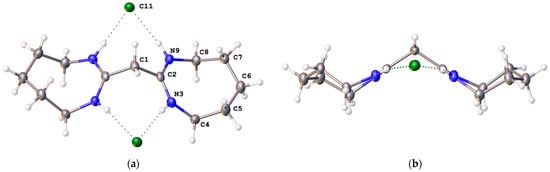

Salt [6H]Cl2 forms in the monoclinic space group I2/a with half of a cation and one chloride in the asymmetric unit (Figure 5a). There is a C2 axis through the central methylene carbon. The amidinium groups are approximately planar with one CH2–N vector forming a 2.2(3)° angle with the CN2 plane while the other methylene forms an angle of 9.0(3)°. The eight-membered ring adopts a chair-like conformation (Figure 5b). The amidinium group is relatively planar with a C1-C2-N3-C4 torsion angle of 177.22(10)°, a C1-C2-N9-C8 torsion angle of 168.12(10)°, and a sum of angles at C2 of 359.99°. The bond distances are similar to those of [4H]Cl2 and [5H]Cl2.

Figure 5.

(a) Labelled solid-state structure of [6H]Cl2; (b) side view of [6H]Cl2 through the amidinium planes.

While there are many examples of solid-state structures of amidinium salts, as well as of diamidinium salts, relatively few of the diamidinium salts have a methylene bridge connecting the central amidinium C atoms. Taylor and coworkers reported the structure of [2dH][GaCl4]2 [12,14], and Clyburne reported [((Me2N)(NHTol)C)2CH2]Cl2.CH2Cl2.2H2O [17]. Both salts have approximately planar CN2 amidinium groups with C–N distances ranging from 1.296(16) to 1.335(16) Å, which is similar to the analogous structures reported here. Although the salt [((Me2N)(NHTol)C)2CH2]Cl2 has two NH groups and two chloride ions, the chloride ions are not chelated by the dications. One chloride forms an alternating water–chloride hydrogen-bonding chain, whereas the other chloride forms hydrogen bonds to two different dications, thereby forming a chain of alternating dications and chloride ions. The two chains are linked by chloride–water–chloride hydrogen-bonding bridges. Schwesinger [23] and Kemnitz [24] reported diamidinium dications which are linked by both methylene bridges at the central amidinium C atoms as well as by an ethylene bridge between N atoms. These are analogous to what would be [3aH]2+, but with a C–C bond between the Me groups.

3.3. Thermal Properties

Thermal decomposition represents the upper limit for the liquid state of an ionic liquid. It is conventionally determined by thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) at a heating rate of 1 or 10 K/min; we used 10 K/min here, which provides useful comparisons with other ILs. Decomposition does begin at lower temperatures, and isothermal studies would be required if information on practical operating temperatures were required more precisely. TGA and DSC data are summarized in Table 1 (see Scheme 8 for a summary of the cation structures).

Table 1.

Thermal properties for allyldiamidinium and diamidinium salts as determined by DSC and TGA at 10 K/min a.

Scheme 8.

Summary of the allyldiamidinium (left) and diamidinium (centre and right) cations discussed in the TGA, viscosity, conductivity, and miscibility/solubility studies.

For the allyldiamidinium series of salts (Figure 6a and Scheme 8), we can consider the effect of different anions (for ILs generally, this depends on the nucleophilicity of the anion [5,25,26,27,28,29]), the effect of N alkylation ([3a]+ versus [3b]+), and the effect of amidinium ring formation ([1b]+ versus [3b]+). For the three cations for which we have TGA results for all of the Cl−, DCA, OTf−, and NTf2− salts ([1b]+, [3a]+, and [3b]+), the chlorides have the lowest Td values (average of 277 °C), followed by the DCA (335 °C) and OTf− and NTf2− salts, which have similar average Td values (405 °C and 409 °C, respectively). This is pretty much in line with expectations [5,25,26,27,28,29]. The effect of N alkylation is variable when comparing [3a]+ and [3b]+. In TAC salts, alkylation significantly increases the Td [3], whereas for these salts with the NTf2− anion, the Td decreases with alkylation, but triflate is approximately the same. For chloride and DCA, it increases. We presume that this is due to the increased steric crowding upon alkylation, which may favour different decomposition routes depending on the nucleophilicity of the anion. Amidinium ring formation, in contrast, unambiguously provides increased stabilization; all four salts of [3b]+ are significantly more stable than the salts of [1b]+ (the average Td values are 385 and 315 °C, respectively). These two cations have a difference of only four H atoms.

Figure 6.

Onset decomposition temperatures at 10 K/min: (a) allyldiamidinium salts; (b) diamidinium salts.

For the diamidinium series of salts (Figure 6b and Scheme 8), we can also consider the effect of different anions, as well as the effect of increasing the alkyl chain length on the N atoms ([4aH]2+–[4cH]2+), the effect of N alkylation ([4H]2+ versus [4aH]2+–[4cH]2+), the effect of the ring size ([4H]2+–[6H]2+), and the effect of amidinium ring formation ([2cH]2+ versus [4H]2+). Again, the NTf2− and OTf− salts are similar on average (399 °C versus 403 °C, respectively), although there may be up to a 30 °C difference for some cations. The dicyanamide salts are again consistently lower in stability (341 °C on average). Interestingly, the chloride salts are similar to the dicyanamide salts in this case. Thus, broadly speaking, the Td values for the allyldiamidinium and diamidinium salts are similar for the NTf2−, OTf−, and DCA salts, whereas the diamidinium chloride salts are more stable than the allyldiamidinium chloride salts. We expect that the reason for the extra stability of the diamidinium chloride salts is the strongly chelated NH–Cl− hydrogen bonding discussed in Section 3.1 (and exhibited in the solid-state structures discussed above), which reduces the nucleophilicity of the chloride ions.

In trisdialkylaminocyclopropenium (TDAC) salts, it was found that the Td is constant with the alkyl chain length, except for those that have multiple Me groups, which have lower stabilities [3]. In the case of the diamidiniums here, there is no such obvious trend, as each anion shows different behaviour from [4aH]2+–[4cH]2+ (see Figure 6b). Similarly, like the allyldiamidiniums and unlike the TAC salts, N alkylation does not give an obvious increase in stability when comparing [4H]2+ to [4aH]2+–[4cH]2+, although in these cases, there are still two NH groups present on the cation, rather than four. In the case of ring size, [4H]2+ has six-membered rings in which five of the atoms are coplanar due to the sp2 hybridization of the three amidinium CN2 atoms, leaving the sixth atom out of the plane so that each atom can reasonably well adopt its preferred geometry. With [5H]2+, however, the seven-membered ring is significantly strained, and the sp2-hybridized atoms can no longer adopt ideal 120° angles (see the solid-state structure below). Thus, the Td for [5H][NTf2]2 is significantly lower than that for [4H][NTf2]2 (368 °C versus 408 °C, respectively), while that for [5H]Cl2 is slightly lower than that for [4H]Cl2 (309 °C versus 329 °C, respectively). In contrast, [6H]Cl2 is much less distorted and, consequently, its Td (330 °C) is similar to that of [4H]Cl2. Chelation of the chlorides may have some impact on the Td by reducing the chloride nucleophilicity and thereby increasing the stability of the salt. As with the ring formation in the allyldiamidinium salts, the ring formation in the diamidinium salts dramatically increases stability; the chloride and bistriflimide salts of [4H]2+ have Td values 75 to 90 °C higher than those of the corresponding salts of [2cH]2+.

With regard to the possible thermal decomposition mechanisms, the relatively small number of compounds studied here makes any conclusions largely speculative. Anion effects seem to have the greatest impact on the Td, suggesting that nucleophilic attack or deprotonation by the anion is the most likely first step. Deprotonation might occur via conversion of cations with NH groups to ketimines (Scheme 4) or conversion of diamidiniums (acidic CH2) to allyldiamidiniums (acidic CH) and then to tetraaminoallenes (Scheme 2). The presence of NH groups, however, does not always result in a lower Tg (compare [3a]+ and [3b]+). Alternatively, dealkylation via anionic nucleophilic attack to yield ketimines (and alkylchlorides in the case of a chloride anion) is another possibility.

The melting point (Tm) represents the lower limit of the liquid range for an ionic liquid. Unfortunately, we were often unable to determine this for the low-melting salts, as highly viscous liquids are frequently slow to crystallize and often do not crystallize during a DSC scan; this can limit the observation of a solid-liquid transition. Also, many of the chloride salts are highly hygroscopic, making the determination of a reliable value for the Tm very difficult. The Tm of a salt depends on a large variety of factors, including the strength of the intermolecular forces, the packing efficiency (relative ion sizes, shapes, and symmetry), and conformational flexibility, and so is generally difficult to predict accurately, although comparisons between similar species are easier to rationalise.

The allyldiamidinium chloride salt [1a]Cl has a very high Tm of 201 °C due to strong electrostatic interactions with the small chloride ion and a relatively inflexible cation. In contrast, [1b]Cl has four-NEtMe groups, which can rotate to generate a wide variety of conformers, as well as four flexible ethyl groups. Thus, the triflate has a Tm of 55 °C, whereas the chloride, bistriflimide, and dicyanamide salts are liquid at ambient temperature.

The Tm values for the bistriflimide and triflate salts of [3a]+ (45.7 °C and 78.5 °C, respectively) are higher than those for the corresponding salts of [3b]+ (<20 °C and 61.1 °C, respectively). Salts of [3a]+ have the potential for hydrogen bonding from two NH groups and have a lack of conformational flexibility, whereas salts of [3b]+ have four flexible ethyl substituents and no NH groups.

The Tm for the diamidinium bistriflimide salts is the lowest for the acyclic [2cH]2+ dication (−43.8 °C), followed by those for the partially alkylated cyclic [4aH]2+ and [4bH]2+ dications, which are both semi-solids at ambient temperature. The non-alkylated cyclic dications [4H]2+, [5H]2+, and [7H]2+ yielded similar but higher Tm values (96.5, 106.9, and 97.4 °C, respectively). The di-n-butyl-substituted cyclic [4cH]2+ gives the highest Tm (121 °C). Thus, the Tm is increased by ring formation (reduced conformational flexibility), whereas the effects of alkylation are highly variable (decrease significantly for Me and Et but increase significantly for Bu). The same trends in the effect of alkylation are seen for the triflate salts: 98.5, 13.8, 18.9, and 139 °C for [4H]2+, [4aH]2+, [4bH]2+, and [4cH]2+, respectively. It is not entirely clear why this might be the case. Decreased numbers of proton donor NH groups should lower the Tm, as is seen for [4aH]2+ and [4bH]2+, but so should an increase in conformational flexibility (which is not seen for [4cH]2+). The chloride salt of acyclic [2cH]2+ has a much higher Tm than that of the bistriflimide salt (49.5 °C versus −43.8 °C), presumably due to increased hydrogen bonding.

3.4. Viscosity and Conductivity

Two of the key properties for an ionic liquid in terms of its potential applications are viscosity and conductivity. Viscosity is important for processes such as flow, stirring, mixing, and reagent diffusion, and it also affects conductivity, which is an important property for electrochemical applications. Viscosity data for diamidinium and allyldiamidinium ILs were collected at 20–90 °C (Figure 7) where possible, and data at 20 and 50 °C are given in Table 2, with the complete data provided in the SI. Conductivity data were collected only for the diamidinium ILs, at 20–90 °C where possible. It should be noted that some of the liquid samples have slightly low C microanalytical results. Impurities are known to have an impact on physical properties. The nature of these impurities is uncertain, but they are possibly due to inefficient drying prior to microanalysis, inefficient anion exchange, or the presence of small amounts of the conjugate acid or base.

Figure 7.

Viscosity data with VFT fits: (a) allyldiamidinium salts and (b) diamidinium salts; and with Litovitz fits: (c) allyldiamidinium salts and (d) diamidinium salts.

Table 2.

Viscosity and conductivity data for allyldiamidinium and diamidinium ionic liquids at 20 and 50 °C a.

For the allyldiamidinium salts, we obtained data for only the non-protic cations [1b]+ and [3b]+, which have very similar molecular weights for the cations of 269.45 and 265.42 g/mol, respectively. The protic cation [3a]+ has a higher viscosity (and melting point), presumably due to increased hydrogen bonding, and we were unable to measure viscosities for its salts. Interestingly, the viscosities of the NTf2− and DCA salts of acyclic [1b]+ (21,500 and 1360 mPa·s, respectively, at 20 °C) are significantly greater than those for the corresponding salts of cyclic [3b]+ (161 and 145 mPa·s, respectively). The acyclic cation [1b]+ has greater conformational flexibility than cyclic [3b]+, but it is not clear why this yields high-viscosity ILs for [1b]+. Compared to TDAC salts, however, even the viscosities of [3b]+ are relatively high: [C3(NEt2)2(NBuMe)]+, which has a similar Mr of 266.45 g/mol, has lower viscosities for the NTf2− and DCA salts (106.2 and 73.7 mPa.s, respectively, at 20 °C). TDAC cations are well known to have weak interactions with their anions, and their viscosities are typically less than those for other IL cations of similar size [3].

The viscosities of dicationic ILs are known to be significantly higher than those of their monocationic analogues. The reasons for this, however, are not as simple as they might appear. For example, the viscosity increases by a factor of 15 times from 1-methyl-3-propylimidazolium bistriflate ([C3Mim]NTf2) to the hexyl-bridged bis(methylimidazolium) salt [C6(Mim)2][NTf2]2 (it is 12 times for [C5Mim]+ to [C10(Mim)2]2+) [30], and yet the charge density of the liquid does not significantly change; the density increases by only 4%, as we have simply removed one H atom from each [C3Mim]+ cation and formed a C–C covalent bond between pairs of cations. However, this increase in density due to cation–cation bond formation also involves a not insignificant 9% decrease in the free volume (based on calculated van der Waals volumes [30]). Notably, increases in viscosity are also highly anion-dependent: for the [BF4]− salts of [C5Mim]+ and [C10(Mim)2]2+, the increase is 78 times [30]. Additionally, viscosities of dicationic ILs are dependent on the separation between the cationic units (which correspond to changes in the local charge density): There is an approximately 10-times increase from [C9(Mim)2][NTf2]2 (443 mPa·s at 303 K, with a C9 linker) to [C10(Im)C1(Mim)][NTf2]2 (about 4800 mPa·s, by extrapolation of VFT parameters, with a C1 linker) [31]. Non-electrostatic contributions to viscosity increases also should not be ignored, as these become quite significant as molecules (or neutral ion clusters?) become larger: the viscosity of decane is 3.8 times that of pentane, whereas that of hexadecane is 6 times that of octane.

The viscosities of the diamidinium salts we measured here (for ILs of [4H]2+, [4aH]2+, and [7H]2+) are significantly higher than those for the allyldiamidinium salts (Figure 7). The DCA salts of these cations all have viscosities greater than 40,000 cP at 20 °C, whereas [4aH][OTf]2 has a viscosity of 6170 cP. Since the molecular weight of [3b]+ is greater than that of [4aH]2+, there is in fact a significant increase in the charge density upon going from the allyldiamidiniums to the diamidiniums described here. Changes in the free volume are likely to be relatively small compared to the changes upon the coupling of two cations, so this increase can largely be attributed to increased electrostatic interactions. Consideration of the increase in viscosity from [C2Mim]DCA (21 mPa·s at 298 K) to [4aH][DCA]2 is perhaps useful, since the molecular weight of the [C2Mim]+ cation is about half that of the [4aH]2+ dication. This increase is 2200 times. If we apply a 78-times increase for cation–cation bond formation (assuming this will be similar for [BF4]− and similarly sized DCA anions), and a 10-times increase for shortening to a C1 linker, then a 3-times increase for either the presence of NH–anion hydrogen bonding or a larger factor of 30 times for the C1 linker (since the 10-times factor was for NTf2− salts, and this could quite reasonably be larger for DCA salts) would give an increase of 2340 times. Although this rationalises the large increase in viscosity, it does not entirely explain why. The strong anion dependence on increases in viscosity, and the increase due to high local charge density (C1 linkers) or high overall charge density ([3b]+ to [4aH]2+), suggests that the formation of significantly larger “solvation” shells of anions around the dication may be largely responsible for the dramatic increases in viscosity for dicationic ILs.

The viscosity of [4H][DCA]2 drops much more slowly than that of the other ILs. It has a similar viscosity to [4aH][DCA]2 at 20 °C, which is much less than that of [7H][DCA]2. At 50 °C, however, it is much greater than both of these ILs. [4H]2+ and [7H]2+ both have four NH groups and would be expected to have greater viscosities than that of [4aH]2+ with two NH groups. The viscosity data were fit to the Arrhenius (η = A·exp(Ea/RT)), Vogel–Fulcher–Tammann (VFT) (η = η0·exp(B/(T − T0))), and Litovitz (ln(η) = A + B*106K3/T3) equations. Some samples were well fitted by Arrhenius plots ([1b]Cl, [1b]DCA, [3b]NTf2, and [4H][DCA]2), which can happen for short temperature ranges. In these cases, the VFT parameters we obtained were found to have very high B (and D) values and low T0 values. These parameters are given in the SI. The Litovitz plots (Figure 7c,d) are generally straight, with a few of them showing slight convex curvature.