Abstract

New Zealand’s only tea (Camellia sinensis) plantation supplies a niche market for organically produced high value tea but faces challenges from climatic conditions and the decision to use only organic production methods. Fungi from the genus Trichoderma have been commercialised in New Zealand and elsewhere as disease-suppressing and plant growth-promoting agents. However, the potential benefits of using Trichoderma as a microbial biostimulant for tea cultivation have not been investigated in New Zealand. The ability of T. atroviride application to stimulate tea plant growth at a tea plantation was investigated over one year of production. The study involved foliar application of the biostimulant either once, twice or three times, one month apart, using 12 g of a commercially formulated spore mixture of four strains of T. atroviride per 5 m2 of experimental plots. Treatment with T. atroviride significantly increased tea yield by between 17% and 28% compared to the control over the harvesting season, but there were no statistically significant yield differences among the number of applications. The foliar applied T. atroviride was not detected in the soil or root samples six months after application, in either a soil metabarcoding analysis or on re-isolation media. This was likely due to the dense tea foliage and ground cover under the tea plants which impeded its movement to the soil. While the specific nature of T. atroviride interaction with perennial crops like tea is not known, in this trial it appeared to have remained on the phyllosphere and provided biostimulation without reaching the soil.

1. Introduction

New Zealanders like their tea, as indicated by a notable increase in per capita tea consumption in recent years. New Zealand’s global ranking increased from 16th place between 2011 and 2013 to 8th place in 2016 Statista [1,2]. In New Zealand, tea cultivation is relatively new and has prioritised quality, sustainability, and ethical sourcing. The only New Zealand tea company, Zealong Tea Estate, produces artisanal tea, with a focus on premium experiences and health benefits [3]. It supplies to niche markets and uses organic production methods, leveraging the unique terroir characterised by fertile soil, clean air, and pristine natural environments. Notably, the plantation has relatively little pest and disease pressure compared to more traditional tea-growing regions where disease pressures are high [3]. The company is dedicated to using sustainable, natural, and chemical-free methods to nourish tea plants and maintain its organic certification status. Despite the lack of disease pressure in New Zealand tea production, around the world, tea is strongly impacted by disease and pests, exacerbated by the physiological stresses caused by tea cultivation and harvesting practices [4]. There are numerous diseases that affect tea [5] which can substantially reduce productivity. Chemical pesticides have been used to control disease and insects pests; however, currently, 17 countries and international organisations have established maximum residue levels (MRL) for over 800 pesticide residues found in tea [6].

The use of microbial biopreparations has been increasing over the last 20 years, with the aim to improve environmental outcomes through sustainable approaches [7]. Microbial inoculants, which are easy to apply, cost effective, and can improve soil health and mitigate plant biotic and abiotic stresses, are increasingly being used as part of long-term sustainable and environmentally-friendly organic farming practices [8,9]. Several species of the genus Trichoderma are among the most widely studied and applied microbial bioinoculants in agriculture [10,11]. Trichoderma species are known for their ability to form symbiotic relationships with plants, for their growth-promoting abilities, and for their biocontrol properties against plant pathogens [12,13]. Trichoderma-based products are sold in many countries, both as pest control products and biofertilizers/biostimulants [14].

Trichoderma atroviride is recognised for its positive interaction with plants and is one of the most commercially formulated and utilised Trichoderma species in global agriculture [15]. T. atroviride is the most prevalent species in New Zealand [16] and has been used for growth promotion and control of plant pathogens in pasture [17,18], Pinus radiata [19], and potatoes [20]. The strain LU132 has been formulated into a range of products sold by Agrimm Technologies Ltd. for mitigation of diseases such as onion white rot and grey mould [21]. The strain was originally isolated from an onion paddock in the North of New Zealand. Trichoderma species, including T. atroviride, can induce both localised and systemic resistance in plants against various pathogens and can directly enhance plant growth and development by alleviating biotic or abiotic stresses [22,23,24]. Foliar-applied Trichoderma can stimulate plant growth by increasing photosynthesis-related protein expression and improving photosynthetic efficiency [25].

While internationally a few studies have successfully used Trichoderma spp. to stimulate tea production [12,26], the use of Trichoderma has not been investigated for improving tea production in New Zealand. Recent evidence confirms that biostimulants can drive measurable improvements in plant performance through indirect mechanisms, including metabolic priming, findings also supported by Salvi et al. [27], who documented significant growth-enhancing activity in treated crops.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of foliar applied T. atroviride on tea leaf production, and to utilise next generation sequencing (NGS) technology to assess the impact of the treatments on the phyllosphere and rhizosphere microbiome of mature tea plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Selection

The study was conducted over a single growth season within a mature tea field at Zealong Tea Estate, located in Gordonton, Hamilton, New Zealand (GPS coordinates: −37.7077007, 175.2998657). The block consisted of 12-year-old tea plants (cv. Jin Xuan), arranged in parallel rows across a one-hectare area. There were approximately 60 tea rows, each 1 m wide and tall, and ranging from 80 to 100 m in length. For the experiment, 32 tea rows were used, excluding the first row from the boundary and commencing 10 m away from the roadside.

2.2. Biostimulant Application

A water-soluble, free-flowing, homogeneous powder of a T. atroviride bioinoculant product was produced by Agrimm Technologies Ltd., Lincoln, New Zealand using equal proportions of spores from four strains of T. atroviride (LU132, LU140, LU584, and LU633). These strains are patented for the biological control of soil-borne pathogens and for promoting plant growth [28,29]. The mixture was applied once, twice, or three times over 3 months (with one month between applications), creating four different treatments: T0—control (no application), T1—three applications, T2—two applications, and T3—one application. Each treatment had eight replicate plots arranged in a completely randomised block design.

The bioinoculant was applied as a foliar spray (Figure 1a) to the top of each 5 m2 plot under light rainy conditions to ensure the spores would wash down the plant and avoid direct sunlight effects. Each plot received 12 g of Trichoderma spores (1 × 108 colony forming units (cfu) per g) dissolved in 6 L of tap water to ensure 2 × 105 cfu/mL of water, uniformly applied using watering cans (Figure 1a). The first application was in August 2022 on all treatment plots. The second and third applications were carried out in September and October 2022 consecutively. Control plots were treated with the same amount of water only. In addition to the biostimulant applications, standard agronomic practices such as trimming, weeding, and fertilising were carried out by company staff. The field relied on natural rainfall (Table S7) as there was no irrigation system.

Figure 1.

(a) Application of T. atroviride spores as a foliar spray, and (b) scale used for data collection.

2.3. Tea Plant Sampling

The leaf harvesting followed the procedure used by the Zealong Tea Estate under their supervision and assistance. Throughout the experimental period, their staff carried out trimming (removal of apical parts to aid consecutive plucking rounds), with the first trimming of the season occurring in early October, two weeks before the third bioinoculant application and six weeks after the first in August. Trimming continued as needed, although the growth removed during this process was not included in the final yields. The focus of the experiment was solely on the harvested tea leaves intended for further processing. During the plucking season in 2022/23, the estate had two harvesting rounds: early December 2022 and early February 2023. An Ochiai V8S-1210 handheld tea leaf harvester was employed to mechanically pluck the top tender tea leaves, with the total harvested leaf weight being recorded using a CAS R323 industrial scale (Figure 1b).

The tea yield data underwent an analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) to compare the mean yield for each treatment using a general linear model in Bonferroni at a significance level of p = 0.05. The analyses were conducted using the GenStat statistical package, 23rd evaluation version 23.0.0.578 (64-bit edition).

2.4. Biostimulant Establishment Within Tea Plants

To determine if the foliar-applied bioinoculant had reached the soil and colonised the mature tea roots, re-isolation from soil and root samples and a microbiome study of tea soil were conducted six months after the first bioinoculant application. Soil samples were randomly collected from the root area close to tea plants at a depth of 15 cm using a 150 mm soil auger. Soil samples were transported to Lincoln University in air-tight, sterile polythene bags. Upon arrival, the samples underwent processing to isolate soil microorganisms and root endophytes, which were then identified through molecular characterisation.

2.4.1. Soil Microorganism Isolation

Soil samples were prepared by breaking any lumps, removing stones and litter, separating the roots, and then mixing well. Ten grams of soil was placed in a sterile 500 mL bottle. One hundred mL of sterile 0.01% TX-100 was added, and the sample was thoroughly homogenised using a Stuart (Staffordshire, UK) flask shaker at 500 rpm for 30 min at room temperature. The initial soil suspension in the culture bottle was considered as 100, from which further dilutions were prepared. Each tube was vortexed to mix for 30 s. One hundred µL of each soil dilution was transferred to two plates of nutrient agar (NA), ½ strength potato dextrose agar (PDA), and Trichoderma selective media (TSM) [30], and spread over the surface.

2.4.2. Root Endophytes Isolation

Tap water-cleaned root samples were surface-sterilised by first soaking them in sterile 0.01% TX-100 for 3 min, then washing them in sterile water followed by a 3 min soak in 2% bleach (1:1 Sodium hypochlorite from Cyclone Premium Bleach and sterile water). In the final step, samples were soaked in 70% ethyl alcohol for 2 min and washed thrice with sterile water. The soaking solutions were changed after every sample and three different forceps were used; when the sample was still dirty, to remove samples from TX and place into bleach and ethanol, and to remove samples from ethanol and handling of clean samples. A root sample cleaned with sterilised water only was used as the non-sterilised root sample.

After aseptic segmentation (about 5 mm in length), 10–12 root segments were placed on two plates of each of NA, ½ strength PDA, and TSM. Before segmenting, surface-sterilised roots were gently pressed on a plate of each media to check for sterilisation efficacy. The same procedure was repeated for the non-sterilised root samples separately after completing the sterilised root inoculation step first. Inoculated plates were incubated at 25 °C with a 12 h light and 12 h dark photoperiod until colonies formed. Starting from the 5th day post-incubation, visually distinguishable bacterial and fungal colonies were sub-cultured onto fresh sterile NA, ½ strength PDA, and TSM agar plates for further development and purification. The process was repeated until a pure colony of each microbe was obtained. For fungi, conidia were observed using a Leica DM2500 (Leica Camera AG, Wetzlar, Germany) microscope with an Olympus SC100 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) camera 10 days post-inoculation.

2.5. Molecular Identification

All isolated and purified bacteria and fungi underwent DNA isolation using a Chelex resin-based method [31,32]. A 5% Chelex solution was prepared by dissolving 2 g of Chelex 100 molecular biology grade resin (BIO-RAD BT, Hercules, CA, USA) in 40 mL of sterile millipure water. For bacterial DNA isolation, fresh overnight cultures were utilised. To generate these cultures, a single colony from each bacterial isolate was selected using a sterile pipette tip and combined with 5 mL of sterile Luria–Bertani Miller broth (LB) in universal bottles. The mixture was then shaken overnight at 25 °C at 250 rpm using a thermostatic incubated shaker (Jeio Tech, Lab Companion, Daejon, Republic of Korea). Subsequently, 1 mL from each overnight culture was transferred to a 1.7 mL tube and centrifuged at 5000× g (relative centrifugal force) for 10 min. The supernatant was then transferred to a new tube, to which 500 µL of 5% Chelex was added and mixed by vortexing.

The fungal DNA extraction process involved using three-day-old pure cultures. A loopful of mycelia from each fungal isolate was transferred into a 1.7 mL tube containing 500 µL of 5% Chelex. The mycelia were macerated with a sterile plastic pestle and then vortexed to mix thoroughly. Subsequently, all the tubes were placed in boiling water for at least 12 min. After cooling to room temperature, the samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 16,000× g to separate the aqueous and particulate phases. Approximately 200 µL of the clear top layer was transferred into new sterile tubes using a sterile filtered tip, labelled, and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

The DNA concentration of each isolate was measured in ng/µL using a 10 mm absorbance path at 230 nm wavelength (λ) of a Nanodrop 3.0.0 spectrophotometer from Nanodrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA. The purity of the extracted DNA was assessed based on the 260/280 and 260/230 absorbance ratios.

The genomic DNA (gDNA) of all bacteria and fungi was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the assistance of a Kyratec thermocycler (Kyratec Pty Ltd., Mansfield, Queesland, Australia) Trinity 2.0.0 revision. Prior to initiating the PCR, each gDNA sample was diluted at a 1:1 ratio by combining 20 µL of PCR water with 20 µL of gDNA. The PCR master mix per reaction was prepared by combining 2.5 µL of PCR buffer 10 × MgCl2, 1 µL of dNTPs, 0.75 µL of each 10 µM forward and reverse primers (Supplementary Table S1), 0.5 µL of Taq polymerase enzyme, and 18.5 µL of PCR water. The quantity of each component was adjusted based on the number of reactions performed simultaneously.

The master mix solution was gently vortexed and spun down before transferring 24 µL into 0.2 mL PCR tubes. Subsequently, 1 µL of each diluted gDNA was added to achieve a final reaction mixture of 25 µL per tube. For the negative control in each cycle reaction, the same reaction mixture with 1 µL of water was used instead of DNA. Prior to loading the tubes in the thermocycler, those with master mix and treatments were briefly spun. The thermal cycle conditions were adjusted based on the type of primers used, as detailed in Supplementary Table S2.

The PCR products’ quality and size were evaluated using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-OH, 20 mM Acetic Acid, pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA). Each well of the agarose gel contained a 5 µL sample of the PCR product and 2 µL of loading dye, with 3 µL DNA gel stain (RedSafeTM, iNtRON Biotechnology, Kirkland, WA, United States) per 40 mL agarose solution. A 1 kb plus DNA ladder (Hyperladder II, Bioline, Taunton, MA, USA) was used to estimate the PCR product sizes. All amplified products were purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel GmBH, Düren, Germany) and sent for sequencing at the Lincoln University Sequencing Unit, Canterbury, New Zealand. The sequences obtained were assembled and verified using ChromasPro software 1.5 (ChromasPro | Technelysium Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia), and the consensus sequences were determined through a BLASTn search after alignment using Geneious 2023.2 [33].

2.6. Soil Analysis

Upon the conclusion of the experiment, 500 g of soil was randomly extracted from each of the four treatments and sent to Hill Laboratories (Hamilton, New Zealand), for the analysis of soil physiochemical properties. The analysis included pH, concentrations of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), cation exchange capacity (CEC), base saturation, weight, extractable sulphur (S) profile, total nitrogen (N), and organic matter [34].

2.7. Tea Soil Microbiome Study

Samples of tea rhizospheric soil before and after T. atroviride foliar application were analysed using metabarcoding technology [11]. Both pre-treatment and post-treatment soil samples were stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

DNeasy PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen N.V., Venlo, Netherlands) was used to extract DNA from soil microorganisms [35]. A 250 mg soil sample from each treatment plot (first 16 plots) and one pre-treatment sample were processed following the manufacturer’s guidelines and recovered dsDNA was quantified using a QubitTM dsDNA BR assay kit (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and QubitTM 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific) for purity. The seventeen extracted DNA samples were stored at −20 °C until further processing through metagenomic DNA barcoding and sequencing. A Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24, (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdon) [36] was used to barcode the amplicons, which involved preparation of a DNA library with ligation of native barcodes and ligating adapters to the DNA ends before nanopore sequencing using MinKNOW 23.04.5 incorporating PromethION 24/48. Two hundred fmol of DNA from each of the 17 soil DNA amplicons were multiplexed with the first 17 native barcodes following the manufacturer’s recommendations given for the Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24, Oxford Nanopore Technologies) [36]. Finally, the base-called and demultiplexed results were further analysed in-depth through bioinformatic workflows available in EPI2ME Labs provided by Oxford Nanopore Technologies Community. Median raw reads accuracy of Q-20 and above were used to interpret the complete microbial profile in rhizosphere soil for each treatment, and the microbiota composition and diversity dynamics were compared to those for the pre-treatment sample.

3. Results

3.1. Tea Plant Yield

The two rounds of harvesting conducted during the 2022/23 season were four and six months after the initial biostimulant application.

The highest tea yield (13.9 t/ha) was achieved following a single application of the biostimulant, a 28% increase over the control (Table 1), which was significantly different using ANOVA (Table S3; d.f 7, s.s 12.328, F. pr. 0.50) and Multiple mean comparison for the total yield using Bonferroni correction at the 5% significance level. There were no significant differences among the treatments receiving the bioinoculant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of foliar application of Trichoderma atroviride on tea yield (total for two harvests). Minimum and maximum individual plot yield given within the brackets, using Bonferroni correction at the 5% significance level.

3.2. Soil Analysis

In comparison with the control, the available nutrients and some physiochemical properties in the Trichoderma treatment plots had decreased (Table 2). For example, for the triple bioinoculant application treatment, Olsen P had decreased by over 10%, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulphur levels had decreased by around 20% and potentially available nitrogen by 7% compared to the levels recorded for the control. However, all four soil samples maintained nutrient levels within the recommended reference range for tea plant growing and had a pH between 4.5 and 5.5.

Table 2.

Summary of basic and additional soil tests for tea soil after biostimulant application. One representative soil sample per treatment was tested by Hill Laboratory Ltd., New Zealand (T0: Control, T1: 3 applications, T2: 2 applications, T3: 1 application). Hill Laboratory report 3224054.

3.3. Confirmation of Biostimulant Establishment Within Tea Plants

Culturing methods did not yield any Trichoderma colonies from the soil. A second test using the same methods resulted in the isolation of five morphologically different fungal colonies from the root samples and eight different fungal colonies from the soil dilution on TSM plates after 10 days of incubation, but none of them were of Trichoderma spp. Molecular identification of the fungi showed a range of common soil fungi (Table 3).

Table 3.

Molecular identification of the isolated root endophytes and soil microbes from Zealong Tea Estate experimental block no. 26. Sampling was undertaken 6 months after the first Trichoderma atroviride application. Sequences were checked using BLASTn.

3.4. Soil Microbiome

Samples of tea rhizospheric soil before and after foliar biostimulant application were analysed using metabarcoding technology.

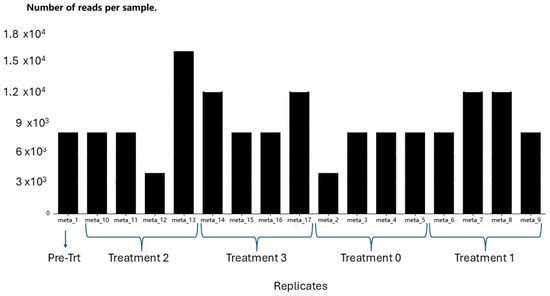

The mean sample amplicons for the pre-treatment, treatment 0 (control), treatment 1 (3 applications), treatment 2 (2 applications), and treatment 3 (1 application) were 8000, 7000, 10,000, 9000, and 10,000 sequences, respectively, over the three replicates. On average, the number of reads per sample in soil samples treated with bioinoculant (T1, T2, and T3) was higher than in the control and pre-treatment rhizospheric soil samples (Figure 2). However, statistically, there were no significant differences among the treatments (p > 0.05) and the analysis of variance for sample read quality and read length also did not show significant differences among the treatments.

Figure 2.

Reads per sample generated through wf-metagenomics nextflow workflow (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Pre-treatment: before biostimulant applied; Treatment 2: two biostimulant applications; Treatment 3: one biostimulant application; Treatment 0: Control/no biostimulant application; and Treatment 1: three biostimulant applications.

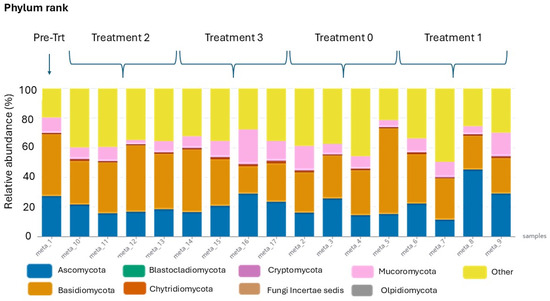

3.5. Taxonomy Comparison

Metagenomic DNA barcoding unveiled numerous amplicon sequence variants, which were categorised into 10 phyla, 49 classes, 141 orders, 395 families, 887 genera, and 2253 species. To facilitate interactive exploration and visual comparison of the hierarchical data at each taxonomic rank, sunburst diagrams were generated by the wf-metagenomics nextflow workflow provided by Oxford Nanopore Technologies for each metagenomic sample (Supplementary Table S4A–E). For simplicity and enhanced visualisation, only the highest taxonomic rank with the fewest number of taxa is presented in Figure 3. The bar plot of the eight most prevalent taxa at the phylum rank indicated a relatively similar abundance of fungal communities in both the pre-treatment and post-treatment samples (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bar plot for the taxonomic comparison of the 8 most abundant fungal taxa at the phylum rank. Any remaining taxa have been collapsed under the “Other” category to facilitate the visualisation. The y-axis indicates the relative abundance of each taxon in percentages for each sample.

From the sixteen samples collected after the treatments, the fungi found were Ascomycota (21.4%), Basidiomycota (32.2%), Chytridiomycota (1.0%), Cryptomycota (0.4%), Mucoromycota (9.8%), Olpidiomycota (<0.1%), and Other (35.2%). In comparison, the pre-treatment sample had the following: Ascomycota (27.4%), Basidiomycota (41.8%), Blastocladiomycota (<0.1%), Chytridiomycota (0.8%), Cryptomycota (0.2%), Fungi Incertae sedis (<0.1%), Mucoromycota (10.3%), and Other (19.6%). Overall, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota were found more frequently than the other four phyla, although the combined “Other” was high. However, the relative abundance of Ascomycota and Other taxa decreased significantly, while that of Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota increased in post-treatment samples compared to the pre-treatment sample.

To conduct a taxonomic comparison, the mean relative abundance of the eight most prevalent fungal phyla at each post-treatment level seven months after the initial inoculation was calculated. The percentage of Ascomycota had increased in treatments 1 and 3 compared to the pre-treatment samples, while the percentage of Basidiomycota had decreased compared to treatment 2 and the control group. Additionally, the percentage of Mucoromycota had slightly increased in treatments 1 and 3 and decreased in treatment 2 compared to the control (Table 4). After performing an arcsine transformation of the percentage data [37] and analysing using a two-way variance, it was determined that there was a statistically significant difference among phyla, but the difference among treatments was not significant (See Supplementary Table S5 for ANOVA).

Table 4.

The mean relative abundance (%) of the 8 most abundant fungal phyla in each treatment.

3.6. Abundance

The wf-metagenomics workflow generated an abundance table, revealing 888 genera across seventeen metabarcoding samples (Supplementary Table S6). Among these, 12 fungal genera recorded more than 1000 total reads across all treatments. These genera were Apiotrichum (29,988), Saitozyma (11,853), Penicillium (8816), Mortierella (7661), Exophiala (6001), Aspergillus (3203), Linnemannia (3142), Basidiobolus (3047), Pseudeurotium (2004), Subulicystidium (1226), Phyllozyma (1170), and Didymella (1162). The remaining 875 genera had fewer than 1000 reads. Additionally, 71.74% of the total reads from all four samples were unclassified and unidentified. The highest number of identified entities belonged to the genus Apiotrichum.

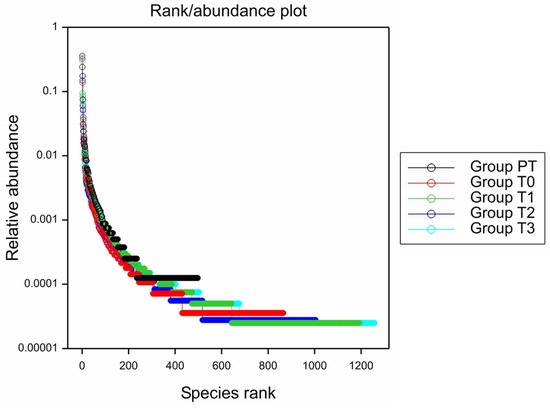

A rank/abundance plot depicts the species abundance dynamics among the treatments (Figure 4). The highest abundance was observed in T3 (one application) with an average of 1257 species, followed by T1 (three applications) (1192), T2 (two applications) (1004), and T0 (control) (865). The pre-treatment soil had the lowest abundance with 497 species. The gentle slopes of the T3 and T1 curves indicated a higher level of species richness and evenness compared to the pre-treatment (PT) and control (T0) plots. Conversely, the steep plots of the PT and T0 treatments, which had low abundance, suggested the presence of dominant assemblages. The T0 assemblage was similar to those found in the pre-treatment soil, which exhibited a high number of reads for a few species and very few reads for all other species.

Figure 4.

Species abundance plot for the average number of species under each treatment (Generated using Genstat).

3.7. Alpha Diversity

The diversity of species in each soil sample was assessed using eight diversity indices generated by the wf-metagenomics nextflow workflow. The average values for each treatment under each index are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean diversity index values for each treatment with ANOVA F-statistic probability.

The analysis of diversity indices revealed that the soil samples treated with bioinoculants displayed higher diversity richness and evenness compared to the control samples. This was evident from the richness index and Shannon diversity index. The effective number of species also indicated slightly greater microbiota diversity in the soil of bioinoculant-treated plants. Among the eight diversity indices examined, Fisher’s Alpha index was the only one to show a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the control (T0) and the single application treatment (T3) (Table S5). The other indices did not demonstrate significant variances in diversity dominance or evenness, based on the separate analyses of variance conducted for each index.

4. Discussion

The application of T. atroviride as a foliar biostimulant significantly enhanced tea yield by 17–28% compared to the untreated control. Notably, a single application proved as effective as multiple applications, suggesting that the establishment of plant–fungal interactions may be more crucial than the quantity of inoculum introduced. This requires investigation, but if confirmed would have important practical implications for commercial tea cultivation, as it indicates that one well-timed application could be sufficient to achieve the desired growth promotion effects. Previous studies using Trichoderma spp. with tea plants have found some reductions in disease occurrence, but few have been trialled in the field [12]. Kumhar et al. [38] used a wettable powder formulation of T. atroviride, T. asperellum, and T. harzianum and reduced incidence of dieback disease in the field. Notably, they found application of T. asperellum and T. harzianum in tea fields significantly increased growth. Application of T. guizhouense promoted the growth of tea cuttings in another study in China, although not all strains resulted in growth increase [39]. The almost complete lack of Trichoderma in the metabarcoding dataset was unexpected, given the significant foliage increase in treated fields.

Although Trichoderma spp. have been previously isolated as endophytes of tea [40,41,42] during re-isolation tests, the foliar-applied T. atroviride was not detected in soil or root samples. This suggests that the yield promotion occurred via phyllosphere activity rather than through root colonisation [43]. The dense canopy of mature tea bushes, combined with artificial weed covers and natural mulch around the plant bases, likely prevented the bioinoculant from reaching the soil. While Trichoderma strains are thought to typically associate with soil and root systems [15], efficient strains like T. atroviride can function effectively as foliar treatments and colonise leaf surfaces under suitable conditions [44,45,46,47].

The soil physicochemical analysis showed no significant differences in nutrient composition among treatments at six months post-foliar application, similar to findings by Hang et al. [48]. However, the reduced nutrient levels in treated plots compared to controls likely reflect increased plant growth and nutrient uptake in Trichoderma-treated plants. The soil C/N ratio increased in order of treatment application frequency (T1 > T2 > T3 > T0), possibly due to competition between soil microorganisms and plants for available nitrogen [49,50]. The soil pH (4.8–4.9) remained ideal for both tea cultivation [51] and Trichoderma establishment [12], though no T. atroviride was recovered during re-isolation.

The microbiome analysis provided novel insights into tea-associated microbial communities in New Zealand. In general, species richness increased in treated plots compared to untreated plots. Trichoderma is known to have antimicrobial activity, such as mycoparasitism, but can also be toxic or competitively displace other microbes. However studies have often shown increases in fungal communities after Trichoderma treatment [52]. In the current study, twelve fungal genera showed high abundance (>1000 reads), with Apiotrichum and Saitozyma displaying particularly high species richness, indicating yeast-rich soil conditions. This may reflect the site’s previous use as a dairy farm and its peaty soils with a tendency for water logging. Such conditions may have impacted Trichoderma establishment, as these fungi prefer environments with more cellulosic material than simple sugars [53]. The relative abundance patterns of Ascomycota in higher-yielding treatments (T1 and T3) compared to lower-yielding ones (T0 and T2) suggests potential synergistic activity between the applied T. atroviride and its broader phylogenetic group. Interestingly, metadata have suggested that Trichoderma/Hypocrea may not be common soil fungi, as suggested in the literature. Previous studies [54,55,56] did not find abundant Trichoderma using culture-independent methods, even when genus-specific primers were used. Friedl [54] and Mesny et al. [57] also suggested that most Trichoderma spp. are outcompeted in a soil environment, which may explain the lack of detection in our metabarcoding study; however, other studies have found Trichoderma persisting [39].

The DNA metabarcoding results six months post-inoculation revealed a correlation between enhanced tea yield and microbial abundance, decreasing in the order of T3 > T1 > T2 > T0 > pre-treatment. While foliar-applied T. atroviride was not detected in the soil microbiome, possibly due to competitive exclusion by closely related organisms [54,58] the treatment appeared to influence broader microbial community composition. Similar effects have been observed in other crops, where Trichoderma-amended treatments stimulated beneficial soil fungi populations and indirectly promoted plant growth through microbiome modulation [48,59,60].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that foliar application of T. atroviride can significantly increase tea production in New Zealand conditions, with a single application proving as effective as multiple treatments. While the precise mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, the growth promotion appears to occur through phyllosphere activity rather than root colonisation. Further research across multiple seasons would help optimise application timing and allow a better understanding of the interaction between Trichoderma and tea plants in a commercial setting. These preliminary findings suggest that T. atroviride could be a valuable tool for sustainable tea cultivation in New Zealand, particularly in an organic production system.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010009/s1, Table S1: Primers used in PCR; Table S2: Thermal cycles used with different primer sets; Table S3: Analysis of variance for the means of total yield for each treatment at the end of the experiment period form Zealong Tea Estate experimental block; Table S4: Sunburst diagram for taxonomic comparison; Table S5: Analysis of variance for mean relative abundance of the eight most abundant fungal phyla in each treatment; Table S6: Abundance table for genus rank; Table S7: Hamilton, New Zealand–monthly temperature and rainfall data (November–October) for 2021/22, 2022/23 and long-term average.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.M.D.S., T.R.G., J.G.H., D.R.W.K.; Methodology: P.M.D.S., D.R.W.K.; Investigation: P.M.D.S., D.R.W.K.; Data curation: P.M.D.S., T.R.G.; Writing-original draft preparation: P.M.D.S., D.R.W.K., T.R.G.; Writing-review and editing: P.M.D.S., T.R.G., J.G.H., D.R.W.K., J.N.; Supervision: T.R.G., J.G.H., D.R.W.K., J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development (AHEAD) programme, a World Bank-funded Sri Lankan government initiative, through a PhD scholarship to undertake this research at Lincoln University, New Zealand. We extend our sincere thanks to Zealong Tea Estate Ltd., New Zealand, particularly Amy Reason (Research and Development Manager), Derek Houghton (Estate Manager), and their staff, for providing access to their commercial tea plantation and facilitating the field experiments. We are grateful to Agrimm Technologies, Lincoln, New Zealand, for supplying the Trichoderma inocula used in this study. Special thanks are due to Christopher Winefield, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Lincoln University, and Bhanupratap Vanga, Research Scientist at Grapevine Improvement, Bragato Research Institute, for their technical expertise and guidance in the DNA metabarcoding analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that Lincoln Agritech Ltd. is wholly owned by Lincoln University. T.R. Glare was fully employed by Lincoln University when this research was completed. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Statista. Global Tea Consumption 2012–2025; Statistica Research Department: Hamburg, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/940102/global-tea-consumption/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Statista. Tea—New Zealand. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/hot-drinks/tea/new-zealand (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Science Learning Hub—Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao. Zealong: A Unique New Zealand Tea. 2013. Available online: https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/1660-zealong-a-unique-new-zealand-tea (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- De Costa, W.A.J.M.; Mohotti, A.J.; Wijeratne, M.A. Ecophysiology of tea. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Sinniah, G.D.; Babu, A.; Tanti, A. How the Global Tea Industry Copes With Fungal Diseases—Challenges and Opportunities. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1868–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.-F.; Fan, C.-L.; Chang, Q.-Y.; Yang, F.; Cao, Y.-Z. Chapter 7.1—The Pre-Collaborative Study of AOAC Method Efficiency Evaluation. In Analysis of Pesticide in Tea; Pang, G.-F., Fan, C.-L., Chang, Q.-Y., Yang, F., Cao, Y.-Z., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 861–881. [Google Scholar]

- Ody, L.P.; Santos, M.S.N.D.; Lopes, A.M.; Mazutti, M.A.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L. Review on biological and biochemical pesticides as a sustainable alternative in organic agriculture. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppeliers, S.W.; Sanchez-Gil, J.J.; de Jonge, R. Microbes to support plant health: Understanding bioinoculant success in complex conditions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Brestic, M.; Bhadra, P.; Shankar, T.; Praharaj, S.; Palai, J.B.; Shah, M.M.R.; Barek, V.; Ondrisik, P.; Skalický, M.; et al. Bioinoculants-Natural Biological Resources for Sustainable Plant Production. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Halim, A.M.A.-A.; Shivanand, P.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Taha, H. A review on the biological properties of Trichoderma spp. as a prospective biocontrol agent and biofertilizer. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, S. Microbes in Soil and Their Metagenomics. In Microbial Diversity, Interventions and Scope; Sharma, S.G., Sharma, N.R., Sharma, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, P.; Bhuyan, R.P.; Sharma, P. Deployment of Trichoderma for the Management of Tea Diseases. In Trichoderma: Host Pathogen Interactions and Applications; Sharma, A.K., Sharma, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, N.A.; Badaluddin, N.A. Biological functions of Trichoderma spp. for agriculture applications. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, T.; Staniszewska, P.; Wiśniewski, P.; Treder, Z.; Przybylski, M.; Wrońska, E.; Maździarz, M.; Krawczyk, K.; Bilska, K.; Paukszto, Ł.; et al. In-depth comparison of commercial Trichoderma-based products: Integrative approaches to quantitative analysis, taxonomy and efficacy. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, M.; Johnston, P.; Ball, S.; Nourozi, F.; Hay, A.; Shoukouhi, P.; Chomic, A.; Lange, C.; Ohkura, M.; Nieto Jacobo, M.; et al. Trichoderma down under: Species diversity and occurrence of Trichoderma in New Zealand. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2016, 46, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.G.; Kandula, D.R.W.; Stewart, A. Development of a Trichoderma atroviride Based Bio-Inoculant for New Zealand’s Pastures; Bio-Protection Research Centre, Lincoln University: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kandula, D.R.W.; Jones, E.E.; Stewart, A.; McLean, K.L.; Hampton, J.G. Trichoderma species for biocontrol of soil-borne plant pathogens of pasture species. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 1052–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regliński, T.; Rodenburg, N.; Taylor, J.T.; Northcott, G.L.; Ah Chee, A.; Spiers, T.M.; Hill, R.A. Trichoderma atroviride promotes growth and enhances systemic resistance to Diplodia pinea in radiata pine (Pinus radiata) seedlings. For. Pathol. 2012, 42, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, E.; Bienkowski, D.; Braithwaite, M.; McLean, K.; Falloon, R.; Stewart, A. Trichoderma strains suppress Rhizoctonia diseases and promote growth of potato. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2014, 53, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.L.; Swaminathan, J.; Frampton, C.M.; Hunt, J.S.; Ridgway, H.J.; Stewart, A. Effect of formulation on the rhizosphere competence and biocontrol ability of Trichoderma atroviride C52. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Doni, F.; Khadka, R.B.; Uphoff, N. Endophytic strains of Trichoderma increase plants’ photosynthetic capability. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. Trichoderma: A multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Hyder, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma Species: Our Best Fungal Allies in the Biocontrol of Plant Diseases-A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoresh, M.; Harman, G.E.; Mastouri, F. Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010, 48, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolandasamy, M.; Mandal, A.K.A.; Balasubramanian, M.G.; Ponnusamy, P. Multifaceted plant growth-promoting traits of indigenous rhizospheric microbes against Phomopis theae, a causal agent of stem canker in tea plants. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, L.; Niccolai, A.; Cataldo, E.; Sbraci, S.; Paoli, F.; Storchi, P.; Rodolfi, L.; Tredici, M.R.; Mattii, G.B. Effects of Arthrospira platensis Extract on Physiology and Berry Traits in Vitis vinifera. Plants 2020, 9, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zijll de Jong, E.; Kandula, J.; Rostás, M.; Kandula, D.; Hampton, J.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A. Fungistatic activity mediated by volatile organic compounds is isolate-dependent in Trichoderma sp. “atroviride B”. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maag, D.; Kandula, D.R.W.; Müller, C.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Wratten, S.D.; Stewart, A.; Rostás, M. Trichoderma atroviride LU132 promotes plant growth but not induced systemic resistance to Plutella xylostella in oilseed rape. BioControl 2014, 59, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, Y.; Chet, I.; Henis, Y. A selective medium for improving quantitative isolation of Trichoderma spp. from soil. Phytoparasitica 1981, 9, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A. DNA Isolation by Chelex Method. In DNA and RNA Isolation Techniques for Non-Experts; Gautam, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, H.; Kandula, D.R.W.; Hampton, J.G.; Stewart, A.; Leung, D.W.M.; Edwards, Y.; Smith, C. Urease producing microorganisms under dairy pasture management in soils across New Zealand. Geoderma Reg. 2017, 11, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. NCBI BLAST: A better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W5–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Laboratories. Agriculture Laboratory—Price List, 43rd ed.; Hill-Laboratories: Frankton, Hamilton, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Standard. User Guide: Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kits; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.: Waltham, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Technologies, O.N. Kit 14 Sequencing and Duplex Basecalling. 2023. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/ja/document/kit-14-device-and-informatics?format=versions (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Warton, D.I.; Hui, F.K.C. The arcsine is asinine: The analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 2011, 92, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumhar, K.C.; Babu, A.; Arulmarianathan, J.P.; Deka, B.; Bordoloi, M.; Rajbongshi, H.; Dey, P. Role of beneficial fungi in managing diseases and insect pests of tea plantation. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2020, 30, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Xiang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Bai, G.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Turning Waste into Wealth: Utilizing Trichoderma’s Solid-State Fermentation to Recycle Tea Residue for Tea Cutting Production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Feng, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Kumar Awasthi, M.; Xu, P. Implications of endophytic microbiota in Camellia sinensis: A review on current understanding and future insights. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, P.M.; Matsumura, E.; Fukuda, K. Effects of Pesticides on the Diversity of Endophytic Fungi in Tea Plants. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.; Sharma, G.D.; Barooah, M. Plant growth promoting endophytic fungi isolated from Tea (Camellia sinensis) shrubs of Assam, India. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2015, 13, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sahib, M.R.; Amna, A.; Opiya, S.O.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.G. Culturable endophytic fungal communities associated with plants in organic and conventional farming systems and their effects on plant growth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, A.; Vinale, F.; Manganiello, G.; Nigro, M.; Lanzuise, S.; Ruocco, M.; Marra, R.; Lombardi, N.; Woo, S.L.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma and its secondary metabolites improve yield and quality of grapes. Crop Prot. 2017, 92, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, H.; Mei, L.; Wang, Y. Trichoderma atroviride LZ42 releases volatile organic compounds promoting plant growth and suppressing Fusarium wilt disease in tomato seedlings. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şesan, T.E.; Oancea, A.O.; Ştefan, L.M.; Mănoiu, V.S.; Ghiurea, M.; Răut, I.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Toma, A.; Savin, S.; Bira, A.F.; et al. Effects of Foliar Treatment with a Trichoderma Plant Biostimulant Consortium on Passiflora caerulea L. Yield and Quality. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.; Meng, L.; Ou, Y.; Shao, C.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, N.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Trichoderma-amended biofertilizer stimulates soil resident Aspergillus population for joint plant growth promotion. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoysa, A.K.N. Organic Tea Cultivation. In Handbook on Tea, 1st ed.; Tea Reseasch Institute of Sri Lanka: Thalawakelle, Sri lanka, 2008; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Jibola-Shittu, M.Y.; Heng, Z.; Keyhani, N.O.; Dang, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y.; Lai, P.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Understanding and exploring the diversity of soil microorganisms in tea (Camellia sinensis) gardens: Toward sustainable tea production. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1379879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. Climatic requirement and soil. In Handbook on Tea, 1st ed.; Zoysa, A.K.N., Ed.; Tea Research Institute of Sri Lanka: Thalawakelle, Sri Lanka, 2008; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jangir, M.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, S. Non-target Effects of Trichoderma on Plants and Soil Microbial Communities. In Plant Microbe Interface; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Mostafa, M.; Rahman, M.R. Growth of Trichoderma spp. with different levels of glucose and pH. Bangladesh J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 22, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, M.A.; Druzhinina, I.S. Taxon-specific metagenomics of Trichoderma reveals a narrow community of opportunistic species that regulate each other’s development. Microbiology 2012, 158, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buée, M.; Reich, M.; Murat, C.; Morin, E.; Nilsson, R.H.; Uroz, S.; Martin, F. 454 Pyrosequencing analyses of forest soils reveal an unexpectedly high fungal diversity. New Phytol. 2009, 1844, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.W.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, C.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, B.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Chun, J. Assessment of soil fungal communities using pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesny, F.; Bauer, M.; Zhu, J.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Meddling with the microbiota: Fungal tricks to infect plant hosts. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2024, 82, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehe, J.; Ortiz, A.; Kulesa, A.; Gore, J.; Blainey, P.C.; Friedman, J. Positive interactions are common among culturable bacteria. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hao, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Tao, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, B.; Shen, Z.; et al. Biodiversity of the beneficial soil-borne fungi steered by Trichoderma-amended biofertilizers stimulates plant production. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L.; Harman, G.E.; Monte, E. Translational research on Trichoderma: From ‘Omics to the field. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010, 48, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.